Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

Martin Buber

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/17/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

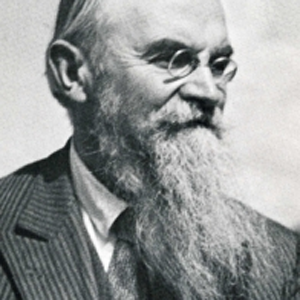

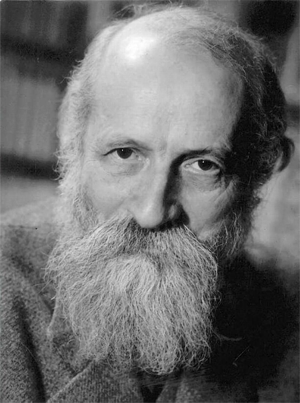

Martin Buber

Born February 8, 1878

Vienna, Austria-Hungary

Died June 13, 1965 (aged 87)

Jerusalem, Israel

Era 20th-century philosophy

Region Western philosophy

School Continental philosophy

Existentialism

Main interests

Ontologyphilosophical anthropology

Notable ideas

Ich-Du (I–Thou) and Ich-Es (I–It)

Influences: Immanuel KantZhuangziSøren KierkegaardFriedrich NietzscheLudwig FeuerbachRalph Waldo EmersonPierre-Joseph ProudhonSigmund FreudJacob L. MorenoWilhelm DiltheyGeorg SimmelRudolf Bultmann

Influenced: Abraham Joshua HeschelWalter KaufmannGabriel MarcelFranz RosenzweigHans Urs von BalthasarFritz PerlsLaura PerlsJohn BergerEmil Brunner[1]

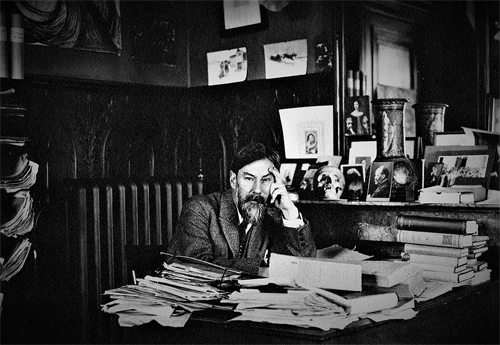

Martin Buber (Hebrew: מרטין בּוּבֶּר; German: Martin Buber; Yiddish: מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 – June 13, 1965) was an Austrian philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship.[2] Born in Vienna, Buber came from a family of observant Jews, but broke with Jewish custom to pursue secular studies in philosophy. In 1902, he became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement, although he later withdrew from organizational work in Zionism. In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou), and in 1925, he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German language.

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times, and Nobel Peace Prize seven times.[3]

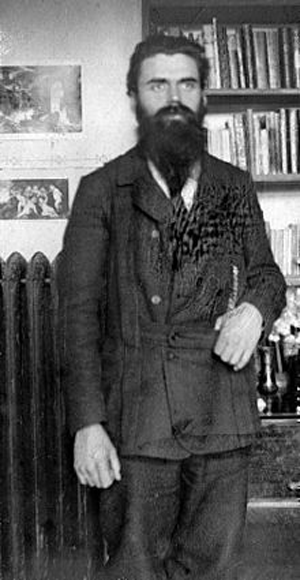

Biography

Martin (Hebrew name: מָרְדֳּכַי, Mordechaj) Buber was born in Der Franz-Josefs-Kai 45 [de]/Heinrichsgasse 8 [de][4][5][6][7][8], der Innere Stadt [de] (1 Wien), City of Vienna, to an Orthodox Jewish family. He was a son of Castiel "Karl" Salomon Buber (Hebrew: קסטיאל "קאַרל" שְׁלֹמֹה בּוּבּר, Yiddish: קסטיאל בּן-שְׁלֹמֹה בּוּבּער, 1848, Lemberg–1935, Lemberg[9][10]), the son of Salomon Buber, and Elise Wurgast (Yiddish: עליזע וווּרגאַסט, 1858, Odessa–?[11]). Buber was a direct descendant of the 16th-century rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, known as the Maharam of Padua. Karl Marx is another notable relative.[12] After the divorce of his parents when he was three years old, he was raised by his grandfather in Lvov.[12] His grandfather Salomon Buber (1827, Lemberg–1906, Lemberg[13]), was a scholar of Midrash and Rabbinic Literature. At home, Buber spoke Yiddish and German. In 1892, Buber returned to his father's house in Lemberg, today's Lviv, Ukraine.

Despite Buber's connection to the Davidic line as a descendant of Katzenellenbogen, a personal religious crisis led him to break with Jewish religious customs. He began reading Immanuel Kant, Søren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche.[14] The latter two, in particular, inspired him to pursue studies in philosophy. In 1896, Buber went to study in Vienna (philosophy, art history, German studies, philology).

In 1898, he joined the Zionist movement, participating in congresses and organizational work. In 1899, while studying in Zürich, Buber met his future wife, Paula (Judith) Buber [de] (née Winkler[15]), a "brilliant Catholic writer from a Bavarian peasant family"[16] who later converted to Judaism.[17]

Buber, initially, supported and celebrated the Great War as a 'world historical mission' for Germany along with Jewish intellectuals to civilize the Near East.[18] While in Vienna, during and after World War I, some researchers claim he was influenced by the writings of Jacob L. Moreno, particularly the use of the term ‘encounter’.[19][20]

In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main, but resigned from his professorship in protest immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body as the German government forbade Jews from public education. In 1938, Buber left Germany and settled in Jerusalem, Mandate Palestine, receiving a professorship at Hebrew University and lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology.

Buber's wife Paula died in 1958, and he died at his home in the Talbiya neighborhood of Jerusalem on June 13, 1965. They had two children: a son, Rafael Buber (husband of Margarete Buber-Neumann née Thüring [de]), and a daughter, Eva Strauss-Steinitz (wife of Ludwig Strauß [de]).[12]

Major themes

Buber's evocative, sometimes poetic, writing style marked the major themes in his work: the retelling of Hasidic and Chinese tales, Biblical commentary, and metaphysical dialogue. A cultural Zionist, Buber was active in the Jewish and educational communities of Germany and Israel.[21] He was also a staunch supporter of a binational solution in Palestine, and, after the establishment of the Jewish state of Israel, of a regional federation of Israel and Arab states. His influence extends across the humanities, particularly in the fields of social psychology, social philosophy, and religious existentialism.[22]

Buber's attitude toward Zionism was tied to his desire to promote a vision of "Hebrew humanism".[23] According to Laurence J. Silberstein, the terminology of "Hebrew humanism" was coined to "distinguish [Buber's] form of nationalism from that of the official Zionist movement" and to point to how "Israel's problem was but a distinct form of the universal human problem. Accordingly, the task of Israel as a distinct nation was inexorably linked to the task of humanity in general".[24]

Zionist views

Approaching Zionism from his own personal viewpoint, Buber disagreed with Theodor Herzl about the political and cultural direction of Zionism. Herzl envisioned the goal of Zionism in a nation-state, but did not consider Jewish culture or religion necessary. In contrast, Buber believed the potential of Zionism was for social and spiritual enrichment. For example, Buber argued that following the formation of the Israeli state, there would need to be reforms to Judaism: "We need someone who would do for Judaism what Pope John XXIII has done for the Catholic Church".[25] Herzl and Buber would continue, in mutual respect and disagreement, to work towards their respective goals for the rest of their lives.

In 1902, Buber became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement. However, a year later he became involved with the Jewish Hasidim movement. Buber admired how the Hasidic communities actualized their religion in daily life and culture. In stark contrast to the busy Zionist organizations, which were always mulling political concerns, the Hasidim were focused on the values which Buber had long advocated for Zionism to adopt. In 1904, he withdrew from much of his Zionist organizational work, and devoted himself to study and writing. In that year, he published his thesis, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems, on Jakob Böhme and Nikolaus Cusanus.[26]

In the early 1920s, Martin Buber started advocating a binational Jewish-Arab state, stating that the Jewish people should proclaim "its desire to live in peace and brotherhood with the Arab people, and to develop the common homeland into a republic in which both peoples will have the possibility of free development".[27]

Buber rejected the idea of Zionism as just another national movement, and wanted instead to see the creation of an exemplary society; a society which would not, he said, be characterized by Jewish domination of the Arabs. It was necessary for the Zionist movement to reach a consensus with the Arabs even at the cost of the Jews remaining a minority in the country. In 1925, he was involved in the creation of the organization Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace), which advocated the creation of a binational state, and throughout the rest of his life, he hoped and believed that Jews and Arabs one day would live in peace in a joint nation. In 1942, he co‑founded the Ihud party, which advocated a bi-nationalist program. Nevertheless, he was connected with decades of friendship to Zionists and philosophers such as Chaim Weizmann, Max Brod, Hugo Bergman, and Felix Weltsch, who were close friends of his from old European times in Prague, Berlin, and Vienna to the Jerusalem of the 1940s through the 1960s.

After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Buber advocated Israel's participation in a federation of "Near East" states wider than just Palestine.[28]

Literary and academic career

Martin Buber's house (1916–38) in Heppenheim, Germany. Now the headquarters of the ICCJ.

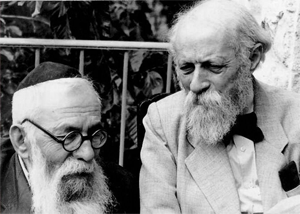

Martin Buber and Rabbi Binyamin in Palestine (1920–30)

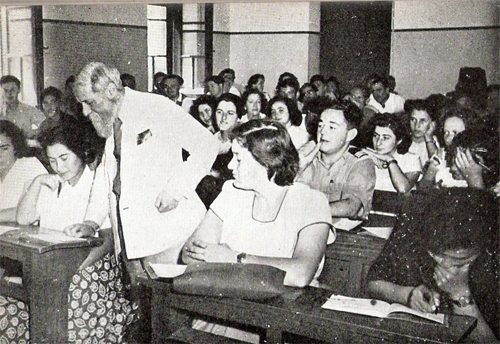

Buber (left) and Judah Leon Magnes testifying before the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry in Jerusalem (1946)

Buber in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem, prior to 1948

From 1906 until 1914, Buber published editions of Hasidic, mystical, and mythic texts from Jewish and world sources. In 1916, he moved from Berlin to Heppenheim.

During World War I, he helped establish the Jewish National Committee[29] to improve the condition of Eastern European Jews. During that period he became the editor of Der Jude (German for "The Jew"), a Jewish monthly (until 1924). In 1921, Buber began his close relationship with Franz Rosenzweig. In 1922, he and Rosenzweig co-operated in Rosenzweig's House of Jewish Learning, known in Germany as Lehrhaus.[30]

In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou). Though he edited the work later in his life, he refused to make substantial changes. In 1925, he began, in conjunction with Franz Rosenzweig, translating the Hebrew Bible into German. He himself called this translation Verdeutschung ("Germanification"), since it does not always use literary German language, but instead attempts to find new dynamic (often newly invented) equivalent phrasing to respect the multivalent Hebrew original. Between 1926 and 1930, Buber co-edited the quarterly Die Kreatur ("The Creature").[31]

In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main. He resigned in protest from his professorship immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. On October 4, 1933, the Nazi authorities forbade him to lecture. In 1935, he was expelled from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (the National Socialist authors' association). He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body, as the German government forbade Jews to attend public education.[32] The Nazi administration increasingly obstructed this body.

Finally, in 1938, Buber left Germany, and settled in Jerusalem, then capital of Mandate Palestine. He received a professorship at Hebrew University, there lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology. The lectures he gave during the first semester were published in the book The problem of man (Das Problem des Menschen);[33][34] in these lectures he discusses how the question "What is Man?" became the central one in philosophical anthropology.[35] He participated in the discussion of the Jews' problems in Palestine and of the Arab question – working out of his Biblical, philosophic, and Hasidic work.

He became a member of the group Ihud, which aimed at a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews in Palestine. Such a binational confederation was viewed by Buber as a more proper fulfillment of Zionism than a solely Jewish state. In 1946, he published his work Paths in Utopia,[36] in which he detailed his communitarian socialist views and his theory of the "dialogical community" founded upon interpersonal "dialogical relationships".

After World War II, Buber began lecture tours in Europe and the United States. In 1952, he argued with Jung over the existence of God.[37]

Philosophy

Buber is famous for his thesis of dialogical existence, as he described in the book I and Thou. However, his work dealt with a range of issues including religious consciousness, modernity, the concept of evil, ethics, education, and Biblical hermeneutics.[38]

Buber rejected the label of "philosopher" or "theologian", claiming he was not interested in ideas, only personal experience, and could not discuss God, but only relationships to God.[39]

Politically, Buber's social philosophy on points of prefiguration aligns with that of anarchism, though Buber explicitly disavowed the affiliation in his lifetime and justified the existence of a state under limited conditions.[40][41]

Dialogue and existence

In I and Thou, Buber introduced his thesis on human existence. Inspired by Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity and Kierkegaard's Single One, Buber worked upon the premise of existence as encounter.[42] He explained this philosophy using the word pairs of Ich-Du and Ich-Es to categorize the modes of consciousness, interaction, and being through which an individual engages with other individuals, inanimate objects, and all reality in general. Theologically, he associated the first with the Jewish Jesus and the second with the apostle Paul (formerly Saul of Tarsus, a Jew).[43] Philosophically, these word pairs express complex ideas about modes of being—particularly how a person exists and actualizes that existence. As Buber argues in I and Thou, a person is at all times engaged with the world in one of these modes.

The generic motif Buber employs to describe the dual modes of being is one of dialogue (Ich-Du) and monologue (Ich-Es).[44] The concept of communication, particularly language-oriented communication, is used both in describing dialogue/monologue through metaphors and expressing the interpersonal nature of human existence.

Ich-Du

Ich‑Du ("I‑Thou" or "I‑You") is a relationship that stresses the mutual, holistic existence of two beings. It is a concrete encounter, because these beings meet one another in their authentic existence, without any qualification or objectification of one another. Even imagination and ideas do not play a role in this relation. In an I–Thou encounter, infinity and universality are made actual (rather than being merely concepts).[44] Buber stressed that an Ich‑Du relationship lacks any composition (e. g., structure) and communicates no content (e. g., information). Despite the fact that Ich‑Du cannot be proven to happen as an event (e. g., it cannot be measured), Buber stressed that it is real and perceivable. A variety of examples are used to illustrate Ich‑Du relationships in daily life—two lovers, an observer and a cat, the author and a tree, and two strangers on a train. Common English words used to describe the Ich‑Du relationship include encounter, meeting, dialogue, mutuality, and exchange.

One key Ich‑Du relationship Buber identified was that which can exist between a human being and God. Buber argued that this is the only way in which it is possible to interact with God, and that an Ich‑Du relationship with anything or anyone connects in some way with the eternal relation to God.

To create this I–Thou relationship with God, a person has to be open to the idea of such a relationship, but not actively pursue it. The pursuit of such a relation creates qualities associated with It‑ness, and so would prevent an I‑You relation, limiting it to I‑It. Buber claims that if we are open to the I–Thou, God eventually comes to us in response to our welcome. Also, because the God Buber describes is completely devoid of qualities, this I–Thou relationship lasts as long as the individual wills it. When the individual finally returns to the I‑It way of relating, this acts as a barrier to deeper relationship and community.

Ich-Es

The Ich-Es ("I‑It") relationship is nearly the opposite of Ich‑Du.[44] Whereas in Ich‑Du the two beings encounter one another, in an Ich‑Es relationship the beings do not actually meet. Instead, the "I" confronts and qualifies an idea, or conceptualization, of the being in its presence and treats that being as an object. All such objects are considered merely mental representations, created and sustained by the individual mind. This is based partly on Kant's theory of phenomenon, in that these objects reside in the cognitive agent’s mind, existing only as thoughts. Therefore, the Ich‑Es relationship is in fact a relationship with oneself; it is not a dialogue, but a monologue.

In the Ich-Es relationship, an individual treats other things, people, etc., as objects to be used and experienced. Essentially, this form of objectivity relates to the world in terms of the self – how an object can serve the individual’s interest.

Buber argued that human life consists of an oscillation between Ich‑Du and Ich‑Es, and that in fact Ich‑Du experiences are rather few and far between. In diagnosing the various perceived ills of modernity (e. g., isolation, dehumanization, etc.), Buber believed that the expansion of a purely analytic, material view of existence was at heart an advocation of Ich‑Es relations - even between human beings. Buber argued that this paradigm devalued not only existents, but the meaning of all existence.

Hasidism and mysticism

Buber was a scholar, interpreter, and translator of Hasidic lore. He viewed Hasidism as a source of cultural renewal for Judaism, frequently citing examples from the Hasidic tradition that emphasized community, interpersonal life, and meaning in common activities (e. g., a worker's relation to his tools). The Hasidic ideal, according to Buber, emphasized a life lived in the unconditional presence of God, where there was no distinct separation between daily habits and religious experience. This was a major influence on Buber's philosophy of anthropology, which considered the basis of human existence as dialogical.

In 1906, Buber published Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman, a collection of the tales of the Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a renowned Hasidic rebbe, as interpreted and retold in a Neo-Hasidic fashion by Buber. Two years later, Buber published Die Legende des Baalschem (stories of the Baal Shem Tov), the founder of Hasidism.[30]

Buber's interpretation of the Hasidic tradition, however, has been criticized by Chaim Potok for its romanticization. In the introduction to Buber's Tales of the Hasidim, Potok claims that Buber overlooked Hasidism's "charlatanism, obscurantism, internecine quarrels, its heavy freight of folk superstition and pietistic excesses, its tzadik worship, its vulgarized and attenuated reading of Lurianic Kabbalah". Even more severe is the criticism that Buber de-emphasized the importance of the Jewish Law in Hasidism.

Awards and recognition

• In 1951, Buber received the Goethe award of the University of Hamburg.

• In 1953, he received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade.

• In 1958, he was awarded the Israel Prize in the humanities.[45]

• In 1961, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[46]

• In 1963, he won the Erasmus Prize in Amsterdam.

Published works

Original writings (German)

• Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman (1906)

• Die fünfzigste Pforte (1907)

• Die Legende des Baalschem (1908)

• Ekstatische Konfessionen (1909)

• Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten (1911)

• Daniel – Gespräche von der Verwirklichung (1913)

• Die jüdische Bewegung – gesammelte Aufsätze und Ansprachen 1900–1915(1916)

• Vom Geist des Judentums – Reden und Geleitworte (1916)

• Die Rede, die Lehre und das Lied – drei Beispiele (1917)

• Ereignisse und Begegnungen (1917)

• Der grosse Maggid und seine Nachfolge(1922)

• Reden über das Judentum (1923)

• Ich und Du (1923)

o Translation: I and Thou by Walter Kaufmann (Touchstone: 1970)

• Das Verborgene Licht (1924)

• Die chassidischen Bücher (1928)

• Aus unbekannten Schriften (1928)

• Zwiesprache (1932)

• Kampf um Israel – Reden und Schriften 1921–1932 (1933)

• Hundert chassidische Geschichten (1933)

• Die Troestung Israels : aus Jeschajahu, Kapitel 40 bis 55 (1933); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Erzählungen von Engeln, Geistern und Dämonen (1934)

• Das Buch der Preisungen (1935); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Deutung des Chassidismus – drei Versuche (1935)

• Die Josefslegende in aquarellierten Zeichnungen eines unbekannten russischen Juden der Biedermeierzeit (1935)

• Die Schrift und ihre Verdeutschung (1936); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Aus Tiefen rufe ich Dich – dreiundzwanzig Psalmen in der Urschrift (1936)

• Das Kommende : Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Messianischen Glaubens – 1. Königtum Gottes (1936 ?)

• Die Stunde und die Erkenntnis – Reden und Aufsätze 1933–1935 (1936)

• Zion als Ziel und als Aufgabe – Gedanken aus drei Jahrzehnten – mit einer Rede über Nationalismus als Anhang (1936)

• Worte an die Jugend (1938)

• Moseh (1945)

• Dialogisches Leben – gesammelte philosophische und pädagogische Schriften (1947)

• Der Weg des Menschen : nach der chassidischen Lehre (1948)

• Das Problem des Menschen (1948, Hebrew text 1942)

• Die Erzählungen der Chassidim (1949)

• Gog und Magog – eine Chronik (1949, Hebrew text 1943)

• Israel und Palästina – zur Geschichte einer Idee (1950, Hebrew text 1944)

• Der Glaube der Propheten (1950)

• Pfade in Utopia (1950)

• Zwei Glaubensweisen (1950)

• Urdistanz und Beziehung (1951)

• Der utopische Sozialismus (1952)

• Bilder von Gut und Böse (1952)

• Die Chassidische Botschaft (1952)

• Recht und Unrecht – Deutung einiger Psalmen (1952)

• An der Wende – Reden über das Judentum (1952)

• Zwischen Gesellschaft und Staat (1952)

• Das echte Gespräch und die Möglichkeiten des Friedens (1953)

• Einsichten : aus den Schriften gesammelt (1953)

• Reden über Erziehung (1953)

• Gottesfinsternis – Betrachtungen zur Beziehung zwischen Religion und Philosophie (1953)

o Translation Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation Between Religion and Philosophy (Harper and Row: 1952)

• Hinweise – gesammelte Essays (1953)

• Die fünf Bücher der Weisung – Zu einer neuen Verdeutschung der Schrift(1954); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Die Schriften über das dialogische Prinzip (Ich und Du, Zwiesprache, Die Frage an den Einzelnen, Elemente des Zwischenmenschlichen) (1954)

• Sehertum – Anfang und Ausgang (1955)

• Der Mensch und sein Gebild (1955)

• Schuld und Schuldgefühle (1958)

• Begegnung – autobiographische Fragmente (1960)

• Logos : zwei Reden (1962)

• Nachlese (1965)

Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten included the first German translation ever made of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Alex Page translated the Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten as "Chinese Tales", published in 1991 by Humanities Press.[47]

Collected works

Werke 3 volumes (1962–1964)

• I Schriften zur Philosophie (1962)

• II Schriften zur Bibel (1964)

• III Schriften zum Chassidismus (1963)

Martin Buber Werkausgabe (MBW). Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften / Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr & Peter Schäfer with Martina Urban; 21 volumes planned (2001–)

Correspondence

Briefwechsel aus sieben Jahrzehnten 1897–1965 (1972–1975)

• I : 1897–1918 (1972)

• II : 1918–1938 (1973)

• III : 1938–1965 (1975)

Several of his original writings, including his personal archives, are preserved in the National Library of Israel, formerly the Jewish National and University Library, located on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem[48]

See also

• Existential therapy

• Guilt

• Humanistic psychology

• Intersubjectivity

• Contextual therapy

• André Neher

• List of Israel Prize recipients

• List of Bialik Prize recipients

• Jewish existentialism

References

1. Livingstone, E. A. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church(3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 79. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199659623.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-965962-3.

2. "Island of Freedom - Martin Buber". Roberthsarkissian.com.

3. "Nomination Database". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

4. "Gedenktafel Martin Buber – Wien Geschichte Wiki". Geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at.

5. "Buber Gedenktafel". Viennatouristguide.at.

6. "Martin Buber und Wien". David.juden.at.

7. "Franz-Josefs-Kai 45 – City ABC". Cityabc.at.

8. "Bild der Woche – Martin-Buber-Geburtshaus". Ojm.at. Retrieved 9 August2019.

9. "Kalman Carl Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

10. "Martin Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

11. "Elise Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

12. Neil Rosenstein (1990), The Unbroken Chain: Biographical Sketches and Genealogy of Illustrious Jewish Families from the 15th–20th Century, 1, 2 (revised ed.), New York: CIS, ISBN 0-9610578-4-X

13. "Salomon (Solomon) Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

14. Wood, Robert E (1 December 1969). Martin Buber's Ontology: An Analysis of I and Thou. Northwestern University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8101-0650-5.

15. "Paula Judith Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

16. The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany 1743-1933. P. 238. (2002) ISBN 0-8050-5964-4

17. "The Existential Primer". Tameri. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

18. Elon, Amos. (2002). The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany, 1743–1933. New York: Metropolitan Books. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 318-319. ISBN 0-8050-5964-4.

19. "Jacob Levy Moreno's encounter term: a part of a social drama" (PDF). Psykodramainstitutt.no. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

20. "Moreno's Influence on Martin Buber's Dialogical Philosophy". Blatner.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

21. Buber 1996, p. 92.

22. Buber 1996, p. 34.

23. Schaeder, Grete (1973). The Hebrew humanism of Martin Buber. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-8143-1483-X.

24. Silberstein, Laurence J (1989). Martin Buber's Social and Religious Thought: Alienation and the quest for meaning. New York: New York University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-8147-7886-0.

25. Hodes, Aubrey (1971). Martin Buber: An Intimate Portrait. p. 174. ISBN 0-670-45904-6.

26. Stewart, Jon (1 May 2011). Kierkegaard and Existentialism. Ashgate. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4094-2641-7.

27. "Jewish Zionist Education". IL: Jafi. May 15, 2005. Archived from the originalon December 22, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

28. Buber, Martin (2005) [1954]. "We Need The Arabs, They Need Us!". In Mendes-Flohr, Paul (ed.). A Land of Two Peoples. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-07802-7.

29. "Martin Buber". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

30. Jump up to:a b Zank, Michael (31 August 2006). New perspectives on Martin Buber. Mohr Siebeck. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-16-148998-3.

31. Buber, Martin; Biemann, Asher D (2002). The Martin Buber reader: essential writings. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-312-29290-4.

32. Buber, Martin (15 February 2005). Mendes-Flohr, Paul R (ed.). A land of two peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07802-1.

33. Buber, Martin (1991), "Martin Buber: A Biographical Sketch", in Schaeder, Grete (ed.), The letters of Martin Buber: a life of dialogue, p. 52, ISBN 978-0-8156-0420-4

34. Buber, Martin, Biemann, Asher D (ed.), The Martin Buber reader: essential writings, p. 12

35. Schaeder, Grete (1973), The Hebrew humanism of Martin Buber, p. 29

36. Buber, Martín (September 1996). Paths in Utopia. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0421-1.

37. Schneider, Herbert W, "The historical significance of Buber's philosophy", The philosophy of Martin Buber, p. 471, ...the retort he actually made, namely, that a scientist should not make judgments beyond his science. Such an insistence on hard and fast boundaries among sciences is not in the spirit of Buber's empiricism

38. Friedman, Maurice S (July 1996). Martin Buber and the human sciences. SUNY Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7914-2876-4.

39. Vermes, Pamela (1988). Buber. London: Peter Hablan. p. vii. ISBN 1-870015-08-8.

40. Brody, Samuel Hayim (2018). "The True Front: Buber and Landauer on Anarchism and Revolution". Martin Buber's Theopolitics. Indiana University Press. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-0-253-03537-0.

41. Silberstein, Laurence J. (1990). Martin Buber's Social and Religious Thought: Alienation and the Quest for Meaning. NYU Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-8147-7910-1.

42. Buber, Martin (2002) [1947]. Between Man and Man. Routledge. pp. 250–51.

43. Langton, Daniel (2010). The Apostle Paul in the Jewish Imagination. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–71.

44. Jump up to:a b c Kramer, Kenneth; Gawlick, Mechthild (November 2003). Martin Buber's I and thou: practicing living dialogue. Paulist Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8091-4158-6.

45. "Recipients" (in Hebrew). Israel Prize. 1958. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012.

46. "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv Municipality. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-17.

47. Chiang, Lydia Sing-Chen. Collecting The Self: Body And Identity In Strange Tale Collections Of Late Imperial China (Volume 67 of Sinica Leidensia). BRILL, 2005. ISBN 9004142037, 9789004142039. p. 62.

48. "Archivbestände in der Jewish National and University Library" (PDF). Uibk.ac.at. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

Sources

Biographies

• Zink, Wolfgang (1978), Martin Buber – 1878/1978.

• Coen, Clara Levi (1991), Martin Buber.

• Friedman, Maurice (1981), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Early Years, 1878-1923.

• Friedman, Maurice (1983), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Middle Years, 1923-1945.

• Friedman, Maurice (1984), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Later Years, 1945-1965.

Further reading

• Schilpp, Paul Arthur; Friedman, Maurice (1967), The philosophy of Martin Buber.

• Horwitz, Rivka (1978), Buber's way to "I and thou" – an historical analysis and the first publication of Martin Buber's lectures "Religion als Gegenwart".

• Cohn, Margot; Buber, Rafael (1980), Martin Buber – a bibliography of his writings, 1897–1978.

• Israel, Joachim (2010), Martin Buber – Dialogphilosophie in Theorie und Praxis.

• Margulies, Hune (2017), Will and Grace: Meditations on the Dialogical Philosophy of Martin Buber.

• Nelson, Eric S. (2017). Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy in Early Twentieth-Century German Thought London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781350002555.

External links

• Literature by and about Martin Buber in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

• Martin Buber at Curlie

• Martin Buber Homepage

• Martin Buber – The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article by Sarah Scott

• Zank, Michael. "Martin Buber". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

• Martin Buber, the Anarchist

• Spiritual Community dedicated to Buber's I–Thou philosophy

• Martin Buber's Utopian Israel

• Martin Buber's Final Legacy: "The Knowledge of Man"; by Maurice Friedman.

• Buber's Philosophy as the Basis for Dialogical Psychotherapy and Contextual Therapy; by Maurice Friedman.

• I, thou, and we: A dialogical approach to couples therapy

• Dialogical and Person-Centred Approach to Psychotherapy

• Communitarian Elements in Select Works of Martin Buber

• The Martin Buber Institute for Dialogical Ecology

• Martin Buber speaks at the Drew University Convocation in 1957. Use the Selected Speakers drop-down to choose Buber, Martin

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/17/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

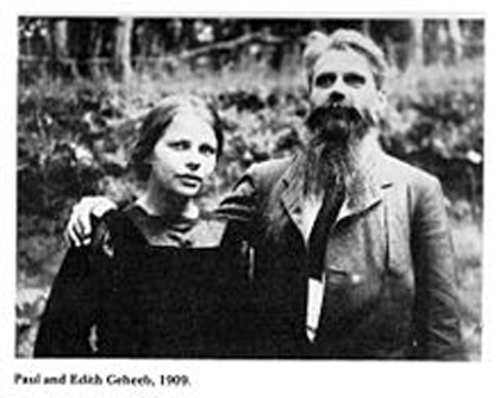

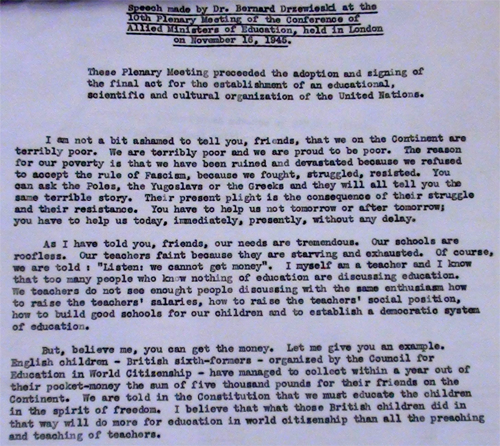

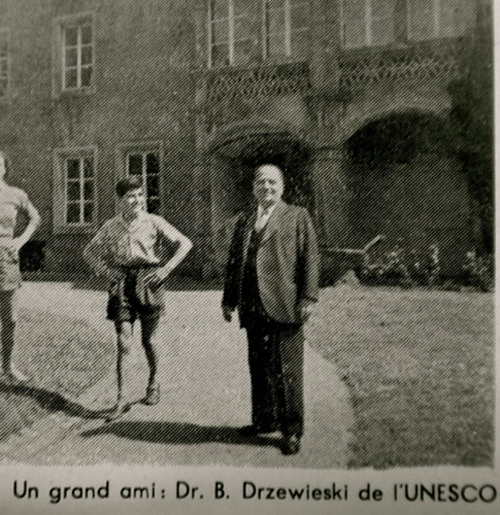

For his 70th birthday, in 1952, Walter Robert Corti wrote an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung of February 15th for the birthday of Elisabeth Rotten, describing this meeting which brings together the faithful of the "educational province" ... ie: John Dewey, Maria Montessori, Martin Buber, Adolphe Ferriere and Bernard Drzewieski.

-- Elisabeth Rotten (1882-1964): A frantic activist of the humanitarian and educational cause and citizen of the world, by Martine Ruchat

The most moving anecdote about Buber was that which his educator friend Elisabeth Rotten related in the introduction to her selection from the revelations of Sister Mechtild von Magdeburg. Speaking directly to Buber, she reminded him of how, six years before, a small circle of his close friends were gathered at his house in lively conversation around his table and how this conversation elicited from Buber a statement that she often found illuminating her way in the years since. "'One must also love the evil,' you said to us, 'yes -- but in the way that the evil wants to be loved.' Your glance said to us still more than your words alone could have said. We had been speaking of the Quakers' belief in the good in all men and of our strong attraction to it but also of the danger of losing sight of the reality of evil.... Your simple words, your embracing glance solved this dark and tormenting riddle of life that had oppressed us."

A significant counterpart to Buber's statement on evil narrated by Elisabeth Rotten is found in his comment on Max Brod's contribution to the special Buber issue of Der Jude. Speaking to Brod of three of his novels, Buber protested: "One may not voluntarily accept evil into one's life. Evil enters our lives entirely willy nilly. To defend ourselves against it, we should always will only to penetrate the impure with the pure. The result will probably be an interpenetration of both elements; still one ought not anticipate that result by saying 'Yes' to the evil in advance." Hermann Hesse testified to the enormous impact on his life of Buber's Hasidic tales; the Christian theologian Friedrich Thieberger wrote of the new biblical belief that he and Buber shared, and many prominent Zionists, such as Leo Hermann, Adolf Bohm, Markus Reiner, Robert Weltsch, Ernst Simon, Viktor Kellner, Felix Weltsch, and Siegfried Lehmann, founder of the Jewish National Home, wrote of Buber's contributions to Zionism and Judaism. Hugo Bergmann contributed a philosophical study of "Concept and Reality" in the thought of Buber and the German Idealist philosopher J.G. Fichte. Several letters from the early correspondence between Buber and Chaim Weizmann were also published in this issue. One contributor even told of how Buber at fifty outran his companions when they left his house for a spontaneous run in the night! "The life of people in this age sucks dry with mighty drafts, strikes out with mighty thrusts," reflected the distinguished writer Arnold Zweig. "But it would have no depth were there not here and there on the earth persons who sit like this man Buber in Heppenheim and give it that tiy injection of iodine without which its fire, spirit, and central creativity would be a mere mechanical process."

-- Martin Buber's Life and Work, by Maurice Friedman

Martin Buber

Born February 8, 1878

Vienna, Austria-Hungary

Died June 13, 1965 (aged 87)

Jerusalem, Israel

Era 20th-century philosophy

Region Western philosophy

School Continental philosophy

Existentialism

Main interests

Ontologyphilosophical anthropology

Notable ideas

Ich-Du (I–Thou) and Ich-Es (I–It)

Influences: Immanuel KantZhuangziSøren KierkegaardFriedrich NietzscheLudwig FeuerbachRalph Waldo EmersonPierre-Joseph ProudhonSigmund FreudJacob L. MorenoWilhelm DiltheyGeorg SimmelRudolf Bultmann

Influenced: Abraham Joshua HeschelWalter KaufmannGabriel MarcelFranz RosenzweigHans Urs von BalthasarFritz PerlsLaura PerlsJohn BergerEmil Brunner[1]

Martin Buber (Hebrew: מרטין בּוּבֶּר; German: Martin Buber; Yiddish: מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 – June 13, 1965) was an Austrian philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship.[2] Born in Vienna, Buber came from a family of observant Jews, but broke with Jewish custom to pursue secular studies in philosophy. In 1902, he became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement, although he later withdrew from organizational work in Zionism. In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou), and in 1925, he began translating the Hebrew Bible into the German language.

He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature ten times, and Nobel Peace Prize seven times.[3]

Biography

Martin (Hebrew name: מָרְדֳּכַי, Mordechaj) Buber was born in Der Franz-Josefs-Kai 45 [de]/Heinrichsgasse 8 [de][4][5][6][7][8], der Innere Stadt [de] (1 Wien), City of Vienna, to an Orthodox Jewish family. He was a son of Castiel "Karl" Salomon Buber (Hebrew: קסטיאל "קאַרל" שְׁלֹמֹה בּוּבּר, Yiddish: קסטיאל בּן-שְׁלֹמֹה בּוּבּער, 1848, Lemberg–1935, Lemberg[9][10]), the son of Salomon Buber, and Elise Wurgast (Yiddish: עליזע וווּרגאַסט, 1858, Odessa–?[11]). Buber was a direct descendant of the 16th-century rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, known as the Maharam of Padua. Karl Marx is another notable relative.[12] After the divorce of his parents when he was three years old, he was raised by his grandfather in Lvov.[12] His grandfather Salomon Buber (1827, Lemberg–1906, Lemberg[13]), was a scholar of Midrash and Rabbinic Literature. At home, Buber spoke Yiddish and German. In 1892, Buber returned to his father's house in Lemberg, today's Lviv, Ukraine.

Despite Buber's connection to the Davidic line as a descendant of Katzenellenbogen, a personal religious crisis led him to break with Jewish religious customs. He began reading Immanuel Kant, Søren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche.[14] The latter two, in particular, inspired him to pursue studies in philosophy. In 1896, Buber went to study in Vienna (philosophy, art history, German studies, philology).

In 1898, he joined the Zionist movement, participating in congresses and organizational work. In 1899, while studying in Zürich, Buber met his future wife, Paula (Judith) Buber [de] (née Winkler[15]), a "brilliant Catholic writer from a Bavarian peasant family"[16] who later converted to Judaism.[17]

Buber, initially, supported and celebrated the Great War as a 'world historical mission' for Germany along with Jewish intellectuals to civilize the Near East.[18] While in Vienna, during and after World War I, some researchers claim he was influenced by the writings of Jacob L. Moreno, particularly the use of the term ‘encounter’.[19][20]

In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main, but resigned from his professorship in protest immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body as the German government forbade Jews from public education. In 1938, Buber left Germany and settled in Jerusalem, Mandate Palestine, receiving a professorship at Hebrew University and lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology.

Buber's wife Paula died in 1958, and he died at his home in the Talbiya neighborhood of Jerusalem on June 13, 1965. They had two children: a son, Rafael Buber (husband of Margarete Buber-Neumann née Thüring [de]), and a daughter, Eva Strauss-Steinitz (wife of Ludwig Strauß [de]).[12]

Major themes

Buber's evocative, sometimes poetic, writing style marked the major themes in his work: the retelling of Hasidic and Chinese tales, Biblical commentary, and metaphysical dialogue. A cultural Zionist, Buber was active in the Jewish and educational communities of Germany and Israel.[21] He was also a staunch supporter of a binational solution in Palestine, and, after the establishment of the Jewish state of Israel, of a regional federation of Israel and Arab states. His influence extends across the humanities, particularly in the fields of social psychology, social philosophy, and religious existentialism.[22]

Buber's attitude toward Zionism was tied to his desire to promote a vision of "Hebrew humanism".[23] According to Laurence J. Silberstein, the terminology of "Hebrew humanism" was coined to "distinguish [Buber's] form of nationalism from that of the official Zionist movement" and to point to how "Israel's problem was but a distinct form of the universal human problem. Accordingly, the task of Israel as a distinct nation was inexorably linked to the task of humanity in general".[24]

Zionist views

Approaching Zionism from his own personal viewpoint, Buber disagreed with Theodor Herzl about the political and cultural direction of Zionism. Herzl envisioned the goal of Zionism in a nation-state, but did not consider Jewish culture or religion necessary. In contrast, Buber believed the potential of Zionism was for social and spiritual enrichment. For example, Buber argued that following the formation of the Israeli state, there would need to be reforms to Judaism: "We need someone who would do for Judaism what Pope John XXIII has done for the Catholic Church".[25] Herzl and Buber would continue, in mutual respect and disagreement, to work towards their respective goals for the rest of their lives.

In 1902, Buber became the editor of the weekly Die Welt, the central organ of the Zionist movement. However, a year later he became involved with the Jewish Hasidim movement. Buber admired how the Hasidic communities actualized their religion in daily life and culture. In stark contrast to the busy Zionist organizations, which were always mulling political concerns, the Hasidim were focused on the values which Buber had long advocated for Zionism to adopt. In 1904, he withdrew from much of his Zionist organizational work, and devoted himself to study and writing. In that year, he published his thesis, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems, on Jakob Böhme and Nikolaus Cusanus.[26]

In the early 1920s, Martin Buber started advocating a binational Jewish-Arab state, stating that the Jewish people should proclaim "its desire to live in peace and brotherhood with the Arab people, and to develop the common homeland into a republic in which both peoples will have the possibility of free development".[27]

Buber rejected the idea of Zionism as just another national movement, and wanted instead to see the creation of an exemplary society; a society which would not, he said, be characterized by Jewish domination of the Arabs. It was necessary for the Zionist movement to reach a consensus with the Arabs even at the cost of the Jews remaining a minority in the country. In 1925, he was involved in the creation of the organization Brit Shalom (Covenant of Peace), which advocated the creation of a binational state, and throughout the rest of his life, he hoped and believed that Jews and Arabs one day would live in peace in a joint nation. In 1942, he co‑founded the Ihud party, which advocated a bi-nationalist program. Nevertheless, he was connected with decades of friendship to Zionists and philosophers such as Chaim Weizmann, Max Brod, Hugo Bergman, and Felix Weltsch, who were close friends of his from old European times in Prague, Berlin, and Vienna to the Jerusalem of the 1940s through the 1960s.

After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Buber advocated Israel's participation in a federation of "Near East" states wider than just Palestine.[28]

Literary and academic career

Martin Buber's house (1916–38) in Heppenheim, Germany. Now the headquarters of the ICCJ.

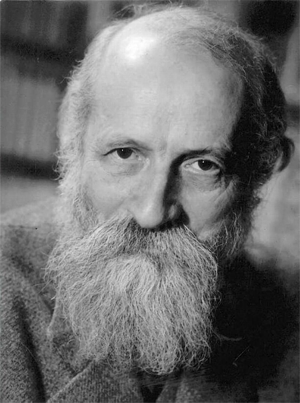

Martin Buber and Rabbi Binyamin in Palestine (1920–30)

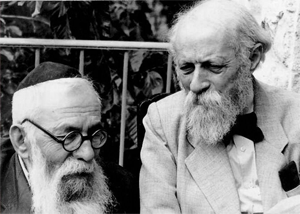

Buber (left) and Judah Leon Magnes testifying before the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry in Jerusalem (1946)

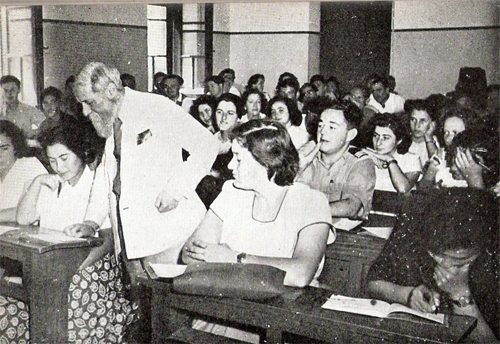

Buber in the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem, prior to 1948

From 1906 until 1914, Buber published editions of Hasidic, mystical, and mythic texts from Jewish and world sources. In 1916, he moved from Berlin to Heppenheim.

During World War I, he helped establish the Jewish National Committee[29] to improve the condition of Eastern European Jews. During that period he became the editor of Der Jude (German for "The Jew"), a Jewish monthly (until 1924). In 1921, Buber began his close relationship with Franz Rosenzweig. In 1922, he and Rosenzweig co-operated in Rosenzweig's House of Jewish Learning, known in Germany as Lehrhaus.[30]

In 1923, Buber wrote his famous essay on existence, Ich und Du (later translated into English as I and Thou). Though he edited the work later in his life, he refused to make substantial changes. In 1925, he began, in conjunction with Franz Rosenzweig, translating the Hebrew Bible into German. He himself called this translation Verdeutschung ("Germanification"), since it does not always use literary German language, but instead attempts to find new dynamic (often newly invented) equivalent phrasing to respect the multivalent Hebrew original. Between 1926 and 1930, Buber co-edited the quarterly Die Kreatur ("The Creature").[31]

In 1930, Buber became an honorary professor at the University of Frankfurt am Main. He resigned in protest from his professorship immediately after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. On October 4, 1933, the Nazi authorities forbade him to lecture. In 1935, he was expelled from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (the National Socialist authors' association). He then founded the Central Office for Jewish Adult Education, which became an increasingly important body, as the German government forbade Jews to attend public education.[32] The Nazi administration increasingly obstructed this body.

Finally, in 1938, Buber left Germany, and settled in Jerusalem, then capital of Mandate Palestine. He received a professorship at Hebrew University, there lecturing in anthropology and introductory sociology. The lectures he gave during the first semester were published in the book The problem of man (Das Problem des Menschen);[33][34] in these lectures he discusses how the question "What is Man?" became the central one in philosophical anthropology.[35] He participated in the discussion of the Jews' problems in Palestine and of the Arab question – working out of his Biblical, philosophic, and Hasidic work.

He became a member of the group Ihud, which aimed at a bi-national state for Arabs and Jews in Palestine. Such a binational confederation was viewed by Buber as a more proper fulfillment of Zionism than a solely Jewish state. In 1946, he published his work Paths in Utopia,[36] in which he detailed his communitarian socialist views and his theory of the "dialogical community" founded upon interpersonal "dialogical relationships".

After World War II, Buber began lecture tours in Europe and the United States. In 1952, he argued with Jung over the existence of God.[37]

Philosophy

Buber is famous for his thesis of dialogical existence, as he described in the book I and Thou. However, his work dealt with a range of issues including religious consciousness, modernity, the concept of evil, ethics, education, and Biblical hermeneutics.[38]

Buber rejected the label of "philosopher" or "theologian", claiming he was not interested in ideas, only personal experience, and could not discuss God, but only relationships to God.[39]

Politically, Buber's social philosophy on points of prefiguration aligns with that of anarchism, though Buber explicitly disavowed the affiliation in his lifetime and justified the existence of a state under limited conditions.[40][41]

Dialogue and existence

In I and Thou, Buber introduced his thesis on human existence. Inspired by Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity and Kierkegaard's Single One, Buber worked upon the premise of existence as encounter.[42] He explained this philosophy using the word pairs of Ich-Du and Ich-Es to categorize the modes of consciousness, interaction, and being through which an individual engages with other individuals, inanimate objects, and all reality in general. Theologically, he associated the first with the Jewish Jesus and the second with the apostle Paul (formerly Saul of Tarsus, a Jew).[43] Philosophically, these word pairs express complex ideas about modes of being—particularly how a person exists and actualizes that existence. As Buber argues in I and Thou, a person is at all times engaged with the world in one of these modes.

The generic motif Buber employs to describe the dual modes of being is one of dialogue (Ich-Du) and monologue (Ich-Es).[44] The concept of communication, particularly language-oriented communication, is used both in describing dialogue/monologue through metaphors and expressing the interpersonal nature of human existence.

Ich-Du

Ich‑Du ("I‑Thou" or "I‑You") is a relationship that stresses the mutual, holistic existence of two beings. It is a concrete encounter, because these beings meet one another in their authentic existence, without any qualification or objectification of one another. Even imagination and ideas do not play a role in this relation. In an I–Thou encounter, infinity and universality are made actual (rather than being merely concepts).[44] Buber stressed that an Ich‑Du relationship lacks any composition (e. g., structure) and communicates no content (e. g., information). Despite the fact that Ich‑Du cannot be proven to happen as an event (e. g., it cannot be measured), Buber stressed that it is real and perceivable. A variety of examples are used to illustrate Ich‑Du relationships in daily life—two lovers, an observer and a cat, the author and a tree, and two strangers on a train. Common English words used to describe the Ich‑Du relationship include encounter, meeting, dialogue, mutuality, and exchange.

One key Ich‑Du relationship Buber identified was that which can exist between a human being and God. Buber argued that this is the only way in which it is possible to interact with God, and that an Ich‑Du relationship with anything or anyone connects in some way with the eternal relation to God.

To create this I–Thou relationship with God, a person has to be open to the idea of such a relationship, but not actively pursue it. The pursuit of such a relation creates qualities associated with It‑ness, and so would prevent an I‑You relation, limiting it to I‑It. Buber claims that if we are open to the I–Thou, God eventually comes to us in response to our welcome. Also, because the God Buber describes is completely devoid of qualities, this I–Thou relationship lasts as long as the individual wills it. When the individual finally returns to the I‑It way of relating, this acts as a barrier to deeper relationship and community.

Ich-Es

The Ich-Es ("I‑It") relationship is nearly the opposite of Ich‑Du.[44] Whereas in Ich‑Du the two beings encounter one another, in an Ich‑Es relationship the beings do not actually meet. Instead, the "I" confronts and qualifies an idea, or conceptualization, of the being in its presence and treats that being as an object. All such objects are considered merely mental representations, created and sustained by the individual mind. This is based partly on Kant's theory of phenomenon, in that these objects reside in the cognitive agent’s mind, existing only as thoughts. Therefore, the Ich‑Es relationship is in fact a relationship with oneself; it is not a dialogue, but a monologue.

In the Ich-Es relationship, an individual treats other things, people, etc., as objects to be used and experienced. Essentially, this form of objectivity relates to the world in terms of the self – how an object can serve the individual’s interest.

Buber argued that human life consists of an oscillation between Ich‑Du and Ich‑Es, and that in fact Ich‑Du experiences are rather few and far between. In diagnosing the various perceived ills of modernity (e. g., isolation, dehumanization, etc.), Buber believed that the expansion of a purely analytic, material view of existence was at heart an advocation of Ich‑Es relations - even between human beings. Buber argued that this paradigm devalued not only existents, but the meaning of all existence.

Hasidism and mysticism

Buber was a scholar, interpreter, and translator of Hasidic lore. He viewed Hasidism as a source of cultural renewal for Judaism, frequently citing examples from the Hasidic tradition that emphasized community, interpersonal life, and meaning in common activities (e. g., a worker's relation to his tools). The Hasidic ideal, according to Buber, emphasized a life lived in the unconditional presence of God, where there was no distinct separation between daily habits and religious experience. This was a major influence on Buber's philosophy of anthropology, which considered the basis of human existence as dialogical.

In 1906, Buber published Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman, a collection of the tales of the Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a renowned Hasidic rebbe, as interpreted and retold in a Neo-Hasidic fashion by Buber. Two years later, Buber published Die Legende des Baalschem (stories of the Baal Shem Tov), the founder of Hasidism.[30]

Buber's interpretation of the Hasidic tradition, however, has been criticized by Chaim Potok for its romanticization. In the introduction to Buber's Tales of the Hasidim, Potok claims that Buber overlooked Hasidism's "charlatanism, obscurantism, internecine quarrels, its heavy freight of folk superstition and pietistic excesses, its tzadik worship, its vulgarized and attenuated reading of Lurianic Kabbalah". Even more severe is the criticism that Buber de-emphasized the importance of the Jewish Law in Hasidism.

Awards and recognition

• In 1951, Buber received the Goethe award of the University of Hamburg.

• In 1953, he received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade.

• In 1958, he was awarded the Israel Prize in the humanities.[45]

• In 1961, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[46]

• In 1963, he won the Erasmus Prize in Amsterdam.

Published works

Original writings (German)

• Die Geschichten des Rabbi Nachman (1906)

• Die fünfzigste Pforte (1907)

• Die Legende des Baalschem (1908)

• Ekstatische Konfessionen (1909)

• Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten (1911)

• Daniel – Gespräche von der Verwirklichung (1913)

• Die jüdische Bewegung – gesammelte Aufsätze und Ansprachen 1900–1915(1916)

• Vom Geist des Judentums – Reden und Geleitworte (1916)

• Die Rede, die Lehre und das Lied – drei Beispiele (1917)

• Ereignisse und Begegnungen (1917)

• Der grosse Maggid und seine Nachfolge(1922)

• Reden über das Judentum (1923)

• Ich und Du (1923)

o Translation: I and Thou by Walter Kaufmann (Touchstone: 1970)

• Das Verborgene Licht (1924)

• Die chassidischen Bücher (1928)

• Aus unbekannten Schriften (1928)

• Zwiesprache (1932)

• Kampf um Israel – Reden und Schriften 1921–1932 (1933)

• Hundert chassidische Geschichten (1933)

• Die Troestung Israels : aus Jeschajahu, Kapitel 40 bis 55 (1933); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Erzählungen von Engeln, Geistern und Dämonen (1934)

• Das Buch der Preisungen (1935); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Deutung des Chassidismus – drei Versuche (1935)

• Die Josefslegende in aquarellierten Zeichnungen eines unbekannten russischen Juden der Biedermeierzeit (1935)

• Die Schrift und ihre Verdeutschung (1936); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Aus Tiefen rufe ich Dich – dreiundzwanzig Psalmen in der Urschrift (1936)

• Das Kommende : Untersuchungen zur Entstehungsgeschichte des Messianischen Glaubens – 1. Königtum Gottes (1936 ?)

• Die Stunde und die Erkenntnis – Reden und Aufsätze 1933–1935 (1936)

• Zion als Ziel und als Aufgabe – Gedanken aus drei Jahrzehnten – mit einer Rede über Nationalismus als Anhang (1936)

• Worte an die Jugend (1938)

• Moseh (1945)

• Dialogisches Leben – gesammelte philosophische und pädagogische Schriften (1947)

• Der Weg des Menschen : nach der chassidischen Lehre (1948)

• Das Problem des Menschen (1948, Hebrew text 1942)

• Die Erzählungen der Chassidim (1949)

• Gog und Magog – eine Chronik (1949, Hebrew text 1943)

• Israel und Palästina – zur Geschichte einer Idee (1950, Hebrew text 1944)

• Der Glaube der Propheten (1950)

• Pfade in Utopia (1950)

• Zwei Glaubensweisen (1950)

• Urdistanz und Beziehung (1951)

• Der utopische Sozialismus (1952)

• Bilder von Gut und Böse (1952)

• Die Chassidische Botschaft (1952)

• Recht und Unrecht – Deutung einiger Psalmen (1952)

• An der Wende – Reden über das Judentum (1952)

• Zwischen Gesellschaft und Staat (1952)

• Das echte Gespräch und die Möglichkeiten des Friedens (1953)

• Einsichten : aus den Schriften gesammelt (1953)

• Reden über Erziehung (1953)

• Gottesfinsternis – Betrachtungen zur Beziehung zwischen Religion und Philosophie (1953)

o Translation Eclipse of God: Studies in the Relation Between Religion and Philosophy (Harper and Row: 1952)

• Hinweise – gesammelte Essays (1953)

• Die fünf Bücher der Weisung – Zu einer neuen Verdeutschung der Schrift(1954); with Franz Rosenzweig

• Die Schriften über das dialogische Prinzip (Ich und Du, Zwiesprache, Die Frage an den Einzelnen, Elemente des Zwischenmenschlichen) (1954)

• Sehertum – Anfang und Ausgang (1955)

• Der Mensch und sein Gebild (1955)

• Schuld und Schuldgefühle (1958)

• Begegnung – autobiographische Fragmente (1960)

• Logos : zwei Reden (1962)

• Nachlese (1965)

Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten included the first German translation ever made of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. Alex Page translated the Chinesische Geister- und Liebesgeschichten as "Chinese Tales", published in 1991 by Humanities Press.[47]

Collected works

Werke 3 volumes (1962–1964)

• I Schriften zur Philosophie (1962)

• II Schriften zur Bibel (1964)

• III Schriften zum Chassidismus (1963)

Martin Buber Werkausgabe (MBW). Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften / Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr & Peter Schäfer with Martina Urban; 21 volumes planned (2001–)

Correspondence

Briefwechsel aus sieben Jahrzehnten 1897–1965 (1972–1975)

• I : 1897–1918 (1972)

• II : 1918–1938 (1973)

• III : 1938–1965 (1975)

Several of his original writings, including his personal archives, are preserved in the National Library of Israel, formerly the Jewish National and University Library, located on the campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem[48]

See also

• Existential therapy

• Guilt

• Humanistic psychology

• Intersubjectivity

• Contextual therapy

• André Neher

• List of Israel Prize recipients

• List of Bialik Prize recipients

• Jewish existentialism

References

1. Livingstone, E. A. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church(3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 79. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199659623.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-965962-3.

2. "Island of Freedom - Martin Buber". Roberthsarkissian.com.

3. "Nomination Database". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

4. "Gedenktafel Martin Buber – Wien Geschichte Wiki". Geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at.

5. "Buber Gedenktafel". Viennatouristguide.at.

6. "Martin Buber und Wien". David.juden.at.

7. "Franz-Josefs-Kai 45 – City ABC". Cityabc.at.

8. "Bild der Woche – Martin-Buber-Geburtshaus". Ojm.at. Retrieved 9 August2019.

9. "Kalman Carl Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

10. "Martin Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

11. "Elise Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

12. Neil Rosenstein (1990), The Unbroken Chain: Biographical Sketches and Genealogy of Illustrious Jewish Families from the 15th–20th Century, 1, 2 (revised ed.), New York: CIS, ISBN 0-9610578-4-X

13. "Salomon (Solomon) Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

14. Wood, Robert E (1 December 1969). Martin Buber's Ontology: An Analysis of I and Thou. Northwestern University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8101-0650-5.

15. "Paula Judith Buber". Geni.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

16. The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany 1743-1933. P. 238. (2002) ISBN 0-8050-5964-4

17. "The Existential Primer". Tameri. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

18. Elon, Amos. (2002). The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany, 1743–1933. New York: Metropolitan Books. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 318-319. ISBN 0-8050-5964-4.

19. "Jacob Levy Moreno's encounter term: a part of a social drama" (PDF). Psykodramainstitutt.no. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

20. "Moreno's Influence on Martin Buber's Dialogical Philosophy". Blatner.com. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

21. Buber 1996, p. 92.

22. Buber 1996, p. 34.

23. Schaeder, Grete (1973). The Hebrew humanism of Martin Buber. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-8143-1483-X.

24. Silberstein, Laurence J (1989). Martin Buber's Social and Religious Thought: Alienation and the quest for meaning. New York: New York University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-8147-7886-0.

25. Hodes, Aubrey (1971). Martin Buber: An Intimate Portrait. p. 174. ISBN 0-670-45904-6.

26. Stewart, Jon (1 May 2011). Kierkegaard and Existentialism. Ashgate. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4094-2641-7.

27. "Jewish Zionist Education". IL: Jafi. May 15, 2005. Archived from the originalon December 22, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

28. Buber, Martin (2005) [1954]. "We Need The Arabs, They Need Us!". In Mendes-Flohr, Paul (ed.). A Land of Two Peoples. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-07802-7.

29. "Martin Buber". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

30. Jump up to:a b Zank, Michael (31 August 2006). New perspectives on Martin Buber. Mohr Siebeck. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-16-148998-3.

31. Buber, Martin; Biemann, Asher D (2002). The Martin Buber reader: essential writings. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-312-29290-4.

32. Buber, Martin (15 February 2005). Mendes-Flohr, Paul R (ed.). A land of two peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07802-1.

33. Buber, Martin (1991), "Martin Buber: A Biographical Sketch", in Schaeder, Grete (ed.), The letters of Martin Buber: a life of dialogue, p. 52, ISBN 978-0-8156-0420-4

34. Buber, Martin, Biemann, Asher D (ed.), The Martin Buber reader: essential writings, p. 12

35. Schaeder, Grete (1973), The Hebrew humanism of Martin Buber, p. 29

36. Buber, Martín (September 1996). Paths in Utopia. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0421-1.

37. Schneider, Herbert W, "The historical significance of Buber's philosophy", The philosophy of Martin Buber, p. 471, ...the retort he actually made, namely, that a scientist should not make judgments beyond his science. Such an insistence on hard and fast boundaries among sciences is not in the spirit of Buber's empiricism

38. Friedman, Maurice S (July 1996). Martin Buber and the human sciences. SUNY Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7914-2876-4.

39. Vermes, Pamela (1988). Buber. London: Peter Hablan. p. vii. ISBN 1-870015-08-8.

40. Brody, Samuel Hayim (2018). "The True Front: Buber and Landauer on Anarchism and Revolution". Martin Buber's Theopolitics. Indiana University Press. pp. 37–40. ISBN 978-0-253-03537-0.

41. Silberstein, Laurence J. (1990). Martin Buber's Social and Religious Thought: Alienation and the Quest for Meaning. NYU Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-8147-7910-1.

42. Buber, Martin (2002) [1947]. Between Man and Man. Routledge. pp. 250–51.

43. Langton, Daniel (2010). The Apostle Paul in the Jewish Imagination. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–71.

44. Jump up to:a b c Kramer, Kenneth; Gawlick, Mechthild (November 2003). Martin Buber's I and thou: practicing living dialogue. Paulist Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8091-4158-6.

45. "Recipients" (in Hebrew). Israel Prize. 1958. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012.

46. "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv Municipality. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-17.

47. Chiang, Lydia Sing-Chen. Collecting The Self: Body And Identity In Strange Tale Collections Of Late Imperial China (Volume 67 of Sinica Leidensia). BRILL, 2005. ISBN 9004142037, 9789004142039. p. 62.

48. "Archivbestände in der Jewish National and University Library" (PDF). Uibk.ac.at. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

Sources

Biographies

• Zink, Wolfgang (1978), Martin Buber – 1878/1978.

• Coen, Clara Levi (1991), Martin Buber.

• Friedman, Maurice (1981), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Early Years, 1878-1923.

• Friedman, Maurice (1983), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Middle Years, 1923-1945.

• Friedman, Maurice (1984), Martin Buber’s Life and Work: The Later Years, 1945-1965.

Further reading

• Schilpp, Paul Arthur; Friedman, Maurice (1967), The philosophy of Martin Buber.

• Horwitz, Rivka (1978), Buber's way to "I and thou" – an historical analysis and the first publication of Martin Buber's lectures "Religion als Gegenwart".

• Cohn, Margot; Buber, Rafael (1980), Martin Buber – a bibliography of his writings, 1897–1978.

• Israel, Joachim (2010), Martin Buber – Dialogphilosophie in Theorie und Praxis.

• Margulies, Hune (2017), Will and Grace: Meditations on the Dialogical Philosophy of Martin Buber.

• Nelson, Eric S. (2017). Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy in Early Twentieth-Century German Thought London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781350002555.

External links

• Literature by and about Martin Buber in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

• Martin Buber at Curlie

• Martin Buber Homepage

• Martin Buber – The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article by Sarah Scott

• Zank, Michael. "Martin Buber". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

• Martin Buber, the Anarchist

• Spiritual Community dedicated to Buber's I–Thou philosophy

• Martin Buber's Utopian Israel

• Martin Buber's Final Legacy: "The Knowledge of Man"; by Maurice Friedman.

• Buber's Philosophy as the Basis for Dialogical Psychotherapy and Contextual Therapy; by Maurice Friedman.

• I, thou, and we: A dialogical approach to couples therapy

• Dialogical and Person-Centred Approach to Psychotherapy

• Communitarian Elements in Select Works of Martin Buber

• The Martin Buber Institute for Dialogical Ecology

• Martin Buber speaks at the Drew University Convocation in 1957. Use the Selected Speakers drop-down to choose Buber, Martin