Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

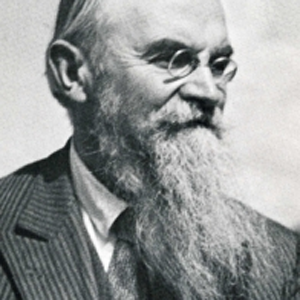

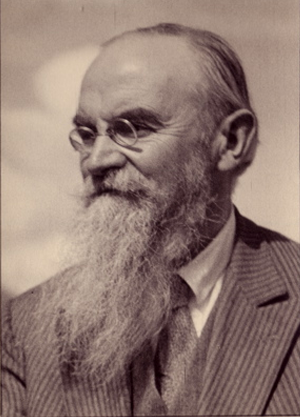

Bernard Drzewieski (1888-1953): A Pole engaged in educational reconstruction

by Mathias Gardet

Published on 04/03/2018

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

Nothing predisposed Bernard Drzewieski to work at Unesco or to take an interest in children's villages. Born on August 2, 1888 in Poland in the city of Lublin in the south-east of the country, he attended school until 1905.

A fervent patriot, he received an international education from an early age: he continued his studies at a secondary school in Odessa in 1906, then, between 1907 and 1908, he left for Switzerland at the University of Geneva and finally in 1909- 1910 at Paris Sorbonne before returning to the University of Warsaw where he graduated from secondary school in 1919, specializing in comparative literature. He worked as a teacher in schools until 1934 , then as headmaster of a college in Warsaw from 1934 to 1939; a profession that is close to his heart and that he militarily seeks to defend values, becoming president of the Polish Union of Secondary School Teachers, then Vice-President of the National Union of Teachers. This national anchorage does not prevent him from attending at this period the network of pedagogues of the International League of New Education for which he writes several articles in the magazine The new Era , becoming itself the secretary general of the Polish branch. In this context he intervenes in Paris at the International Congress of Primary Education and Popular Education organized by the National Union of Teachers and Teachers of France and colonies at the Palace of Mutuality, July 23-31, 1937.

His destiny flips like so many others with war. In September 1939, according to the plan defined by the German-Soviet pact, the German and Soviet armies invaded Poland. Drzewieski first retired to Romania where he became an education advisor for the Polish Refugee Committee, before fleeing with his wife Wanda Schoeneich in 1940 to England, joining the Władysław Raczkiewicz government in exile in London. He then holds the position of Head of the Department of Education within the Ministry of Social Affairs, although his activities are primarily strategic-military in connection with the resistance movement in Poland.

Joint Meeting of the Government of the Republic of Poland and the National Council with the participation of the President of the Republic of Poland Władysław Raczkiewicz in London. 1940 - 1943. Fot. NAC

In addition to learning English, this trip to London is crucial for the future UN career of Drzewieski. It collaborates with the Council of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME), created in 1942 and is already beginning to prepare a plan to rebuild education in devastated countries; a theme dear to Drzewieski given his past as a teacher and echoes that come to him destruction in his country.

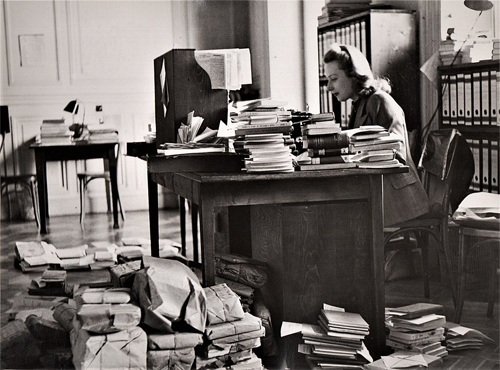

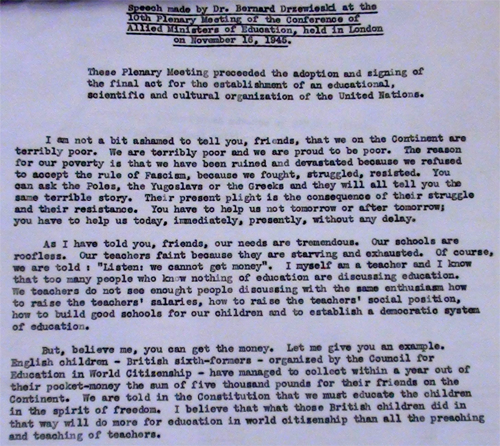

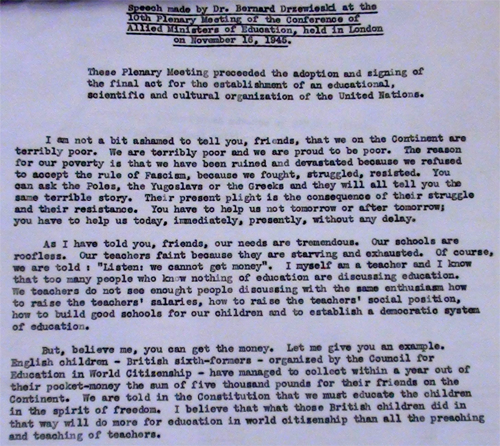

Speech by B. Dzrewieski at the 10th Plenary Assembly of the Conference of Allied Ministers for Education in London on November 16, 1946

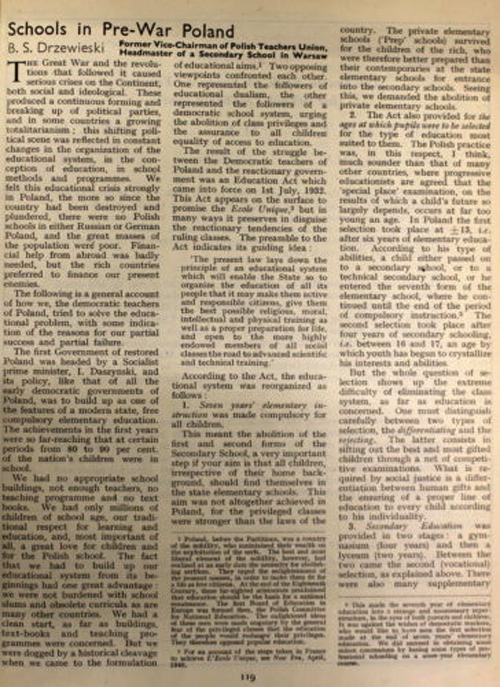

In particular, he is invited to give lectures on education throughout the Kingdom. On this occasion he wrote a long article in the English magazine New Era of the International League of New Education on Schools in Poland before the war.

In 1945, he was appointed Cultural Attaché of the Polish Embassy in London, which means he followed the line of his political leader, Stanisław Mikołajczyk (successor of Raczkiewicz after his death in a plane crash in 1943). who agrees to return to Poland to unite with the Polish National Liberation Committee or "Lublin Committee", the provisional governmental body formed on 23 July 1944 on the initiative of the Soviet Union. A dissident Polish government continues to exist at the same time , but the United States and Great Britain withdraw its approval on July 6, 1945, and they must evacuate the Polish Embassy from Portland Place. Most of its members, unable to return safely to communist Poland, settled in other countries.

It was therefore as a cultural attaché that Drzewieski was appointed member of the Polish delegation to the November 1945 conference which preceded the Preparatory Commission for Unesco, of which he would later become Vice-President.

@UNESCO, Ellen Wilkinson, Minister of Education of Great Britain, reading the UNESCO Constitutive Act aloud at the 1945 conference

He made a fiery speech during which he proclaimed in the name of the European continent his pride of being poor, a poverty due to the refusal to submit to the laws of fascism and made himself the apostle of the needs for educational reconstruction:

Our schools - he says - are homeless, our teachers are failing because they are hungry and exhausted. Of course, we hear people say, "Listen, we can not get money." I am a teacher myself and I know that far too many people who do not know anything about education are discussing education. We teachers do not see enough people to discuss with equal enthusiasm a salary increase, or an improvement in the social status of teachers, or how to build good schools for our children and establish a democratic education system. But, believe me, you can get money.

He cites as an example the initiative undertaken by British children who, under the auspices of the Council for Education for Global Citizenship, would have managed to gather in less than a year with their pocket money the sum of five thousand books to help their distressed counterparts on the continent.

On October 16, 1946, he received a letter from Julian Huxley, the Executive Secretary of Unesco House, located at 19 Avenue Kleber in Paris, proposing that he join the reconstruction section of the same commission; offers that it is obliged to postpone temporarily, given its role as representative of the Polish government, until the holding of the first general conference of 16 November 1946 in London which officially gives birth to Unesco.

Stamp issued on the occasion of the first UNESCO Conference in Paris in 1946

However, he agrees to start informal contacts with the various bodies involved in the reconstruction. At the general conference, Drzewieski represents both the Polish delegation and is rapporteur at the first session of the commission for the reconstitution of education, art and culture. It defines the role of Unesco in the following way: it is responsible for stimulating both the relief provided by governmental and non-governmental agencies of donor countries as well as the production of educational supplies and equipment. ; it is even envisaged that it can undertake and finance certain projects itself.

A few days later, during the meeting held in Paris at Unesco House, 19 Avenue Kleber on November 25, 1946, he was elected president of this commission and declared that from now on he would cease to represent his country to be as the representative of the Unesco Conference. He stressed the coordinating role that Unesco could play between governmental organizations and private non-governmental organizations. A discussion then begins as to whether it should be a clearing house for information and propaganda, but also for receiving and distributing money and materials for aid to devastated countries, or a mere liaison between organizations, works, universities, schools.

Unesco in the walls of the Majestic Hotel, Paris (Unesco photo)

He held this position until January 1947, when he officially joined the Unesco Secretariat as Head of the Department of Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of the Education System. On his job description, he says he speaks fluent Polish and Russian, although French, Italian and English, correctly German. He moved to Paris at 44 rue Hamelin in the 16th arrondissement, although he made many tours abroad. For the year 1947 alone, he traveled to the United States from 25 February to 8 April, to Switzerland from 5 to 16 July, to Czechoslovakia and Poland from 7 August to 11 September, and again to the United States from December 7th to 17th.

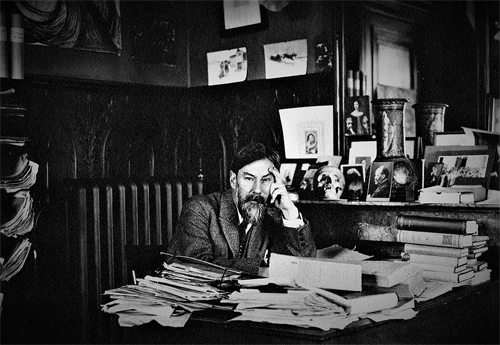

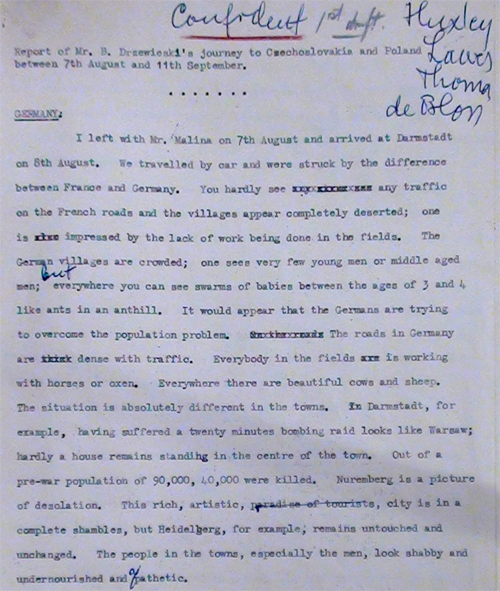

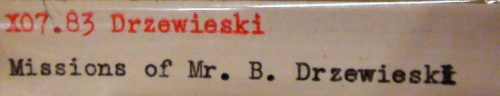

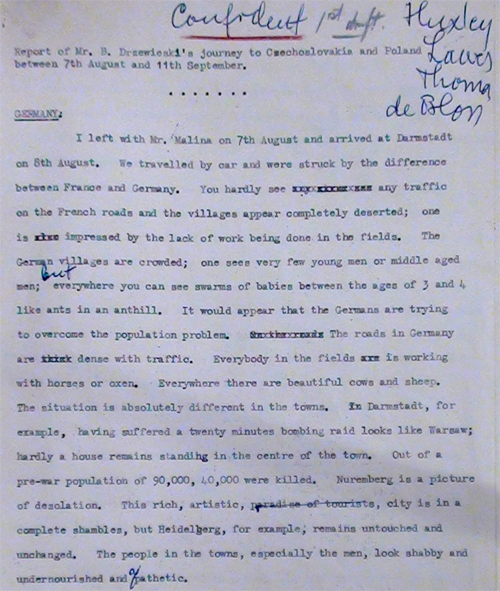

Excerpt from B. Dzrewieski's Confidential Mission Report for Poland, August 7 to September 11, 1947

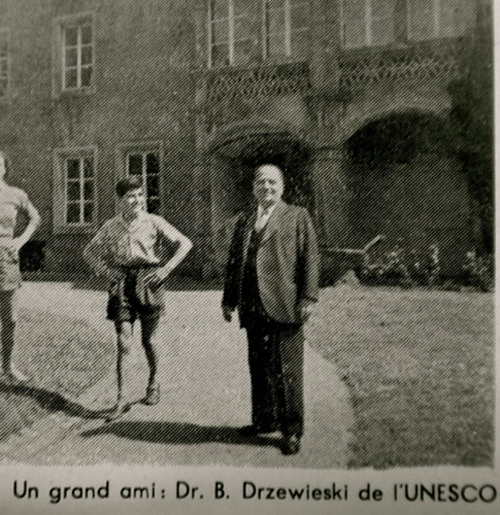

These journeys consist primarily of establishing diplomatic relations: to see how governments perceive Unesco and whether a national commission exists; explain the purpose of the latter; contact schools and their administrators, groups of teachers, publishers and distributors of educational books and various national or international self-help organizations such as the International Bureau of Education, CIER (American Commission for Rebuilding) the International Children's Fund , UNRRA, UIPE, to better coordinate fundraising or school materials; or, in devastated countries, assess the needs in terms of rebuilding schools and helping teachers. It was also during these trips that he visited not only the reconstruction camps, of which he admired the phenomenon of solidarity and international understanding , but also successively the Pestalozzi children's village of Trogen, which he described as the most astonishing and inspiring. business of post-war Europe.

Drzewieski points out the difficulty of such an undertaking when it comes to bringing together Polish children and German children, but optimistically asserts that the organizers are well prepared to provoke these encounters between children of former enemy countries by showing them for example, photos of cities in ruins in their respective countries , in order to awaken in them a community of suffering and experiences. He emphasizes the need to provide the founders of the village with substantial assistance , so that they can build more houses to accommodate another two hundred children and thus become an "experimental laboratory" for the establishment of other international villages in the area. 'other countries. Following a suggestion by the organizers of Trogen who would like Unesco to have some sort of patronage, Drzewieski proposes to organize as soon as possible a conference, under the auspices of his department, bringing together the leaders of different villages of children. which , it seems , already exist in several countries such as Germany, Denmark, France, Hungary, Poland, to reflect on a general pattern for this movement.

The following month, he notes with satisfaction that such is indeed the case in his own country in which he finally has the opportunity to return. He visits the village of Otwook, where 600 children are housed in a former sanatorium near Warsaw, also financed by the Swiss Don. According to him, such a concentration of homeless children rests on the question of the educational orientation that must be offered to them and the urgency of organizing as soon as possible a debate about a possible program to be built in the spirit or not. from Trogen.

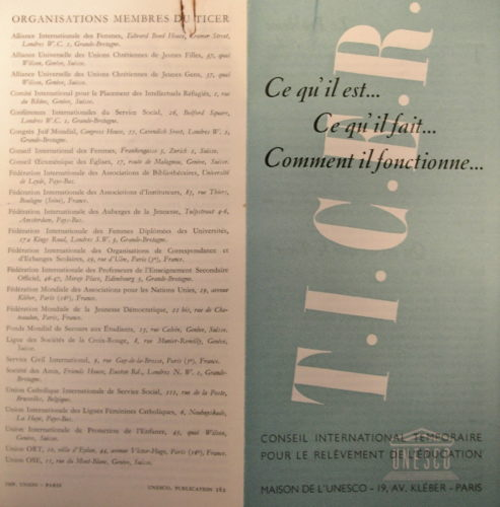

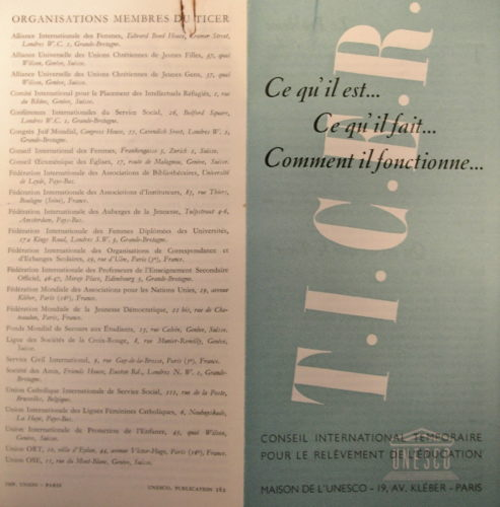

Moreover, in order to meet the first objective of coordinating the collection activities carried out by the various non-governmental organizations, Drzewieski organizes three meetings which end up giving birth, during the last one which takes place in Paris on 23-24 September 1947 at the Unesco House, at the International Temporary Council for the Rehabilitation of Education (Ticer).

Unesco Archives 361.9 A 01

If he presides over this meeting, he wishes to mark the difference between his section of reconstruction and the new private status coordinating body thus created and withdraws from the elected board of directors after having given the final chairmanship to George E. Haynes , president of the international conference of the social service. However, he continues to provide the secretariat.

If during his presentation of the work undertaken by his service in 1947, Drzewieski announced his visit to the village Pestalozzi, he insists especially on the task of educational reconstruction in the field of education that he believes must lead urgently Ticer he thus mentions the situation in Poland and Czechoslovakia, where he has seen eleven different classes operate on a rotating basis in a single room, and for this reason have been obliged to abolish classes in music, singing, physical education and drawing, or There are also courses in cellars, schools with roofs destroyed or ancient mass graves used as playgrounds for children.

At the second session of the Unesco General Conference in Mexico City on 17 November 1947, Drzewieski resumed the idea of collecting precise information on successful experiences in the rehabilitation of children during the war and asked that the Provides support to international children's villages, which it says are "a new and growing initiative"; he proposes again to convene a conference of leaders of these villages to "study ways of integrating them into the official education system of the different countries" .

Just after the Mexico City conference and throughout the first half of 1948, Drzewieski became one of the masters of the convocation of children's village directors and several experts who Trogen on 4-18 July.

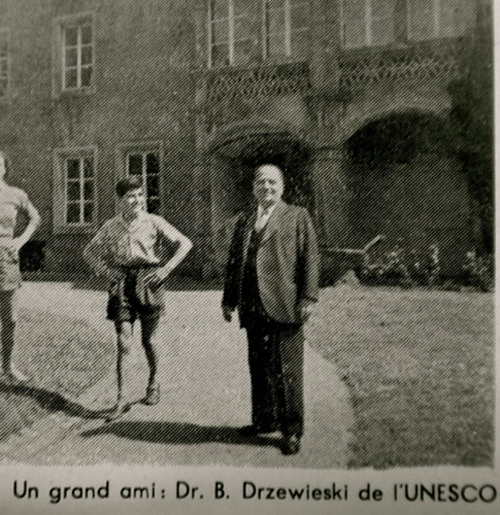

Arrival of the first delegates, including Bernard Drzewieski (3rd from right) in Trogen in July 1948

Bernard Drzewieski and Carleton Washburne at the Trogen Conference in July 1948

These experiences thus become for him an important axis of educational reconstruction, as shown by the introduction of this theme of children's villages through him in Ticer's resolutions and plans of action from March 1948. Although he was called to order by his supervisory ministry, who informed him in 1949 that the free leave granted by Foreign Affairs was coming to an end and that he had to return to a position in the latter, Bernard Drzewieski decided to stay in function at Unesco. In this capacity, he participates in many events organized by FICE, such as international youth camps.

Visit of Bernard Dzrewieski during the Second International Children's Camp at Château de Sanem (Luxembourg), 1950

Visit of Bernard Dzrewieski during the Second International Children's Camp at Sanem Castle in July 1950

Once his first contract is over in the rebuilding department, he is recruited as a program specialist for the Education Department on the subject of education for international understanding , and as special advisor to the section " education for living in a global community.

Bernard Drzewieski (1st on the left) at the FICE Congress in Florence in March 1952

He died at this post in Paris, August 13, 1953, his funeral taking place on Saturday, August 18 in the strictest intimacy.

Bernard Dzrewieski's grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery

His Wanda wife who has always been at his side as a "housewife" and faithful secretary without attribution, finds herself in great economic difficulty given the meager pension she receives on the death of her husband, housed first by colleagues of the latter, she finally left Paris to return to Poland in 1956 thanks to exceptional aid from Unesco.

Sources

Unesco Archives, Paris:

• Staff file of B. Dzrewieski. Box 106 PER / REC.1 / 106, 1965

• X07.83 Missions of B. Dzrewieski.

• 371.95 A 06 (494) "48". Conference on War Handicapped Children (Trogen 5-10 / VII / 48).

Archives of the Institute of Education in London

• dossier on the Polish section of the New Education Fellowship, WEF / A / II / 144

Bibliography

Boussion (Samuel), Gardet (Mathias), Ruchat (Martine), "Bringing everyone to Trogen: Unesco and the Promotion of an International Model of Children's Communities after World War II", Duedhal (Poul) (eds.), A History of Unesco.Global Actions and Impacts , London, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016, p. 99-115.

Unesco, The Book of Needs of Fifteen War-Devastated Countries in Education, Science and Culture , c. 1, Paris, Unesco, 1947, 111 p.

by Mathias Gardet

Published on 04/03/2018

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Nothing predisposed Bernard Drzewieski to work at Unesco or to take an interest in children's villages. Born on August 2, 1888 in Poland in the city of Lublin in the south-east of the country, he attended school until 1905.

A fervent patriot, he received an international education from an early age: he continued his studies at a secondary school in Odessa in 1906, then, between 1907 and 1908, he left for Switzerland at the University of Geneva and finally in 1909- 1910 at Paris Sorbonne before returning to the University of Warsaw where he graduated from secondary school in 1919, specializing in comparative literature. He worked as a teacher in schools until 1934 , then as headmaster of a college in Warsaw from 1934 to 1939; a profession that is close to his heart and that he militarily seeks to defend values, becoming president of the Polish Union of Secondary School Teachers, then Vice-President of the National Union of Teachers. This national anchorage does not prevent him from attending at this period the network of pedagogues of the International League of New Education for which he writes several articles in the magazine The new Era , becoming itself the secretary general of the Polish branch. In this context he intervenes in Paris at the International Congress of Primary Education and Popular Education organized by the National Union of Teachers and Teachers of France and colonies at the Palace of Mutuality, July 23-31, 1937.

His destiny flips like so many others with war. In September 1939, according to the plan defined by the German-Soviet pact, the German and Soviet armies invaded Poland. Drzewieski first retired to Romania where he became an education advisor for the Polish Refugee Committee, before fleeing with his wife Wanda Schoeneich in 1940 to England, joining the Władysław Raczkiewicz government in exile in London. He then holds the position of Head of the Department of Education within the Ministry of Social Affairs, although his activities are primarily strategic-military in connection with the resistance movement in Poland.

Joint Meeting of the Government of the Republic of Poland and the National Council with the participation of the President of the Republic of Poland Władysław Raczkiewicz in London. 1940 - 1943. Fot. NAC

In addition to learning English, this trip to London is crucial for the future UN career of Drzewieski. It collaborates with the Council of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME), created in 1942 and is already beginning to prepare a plan to rebuild education in devastated countries; a theme dear to Drzewieski given his past as a teacher and echoes that come to him destruction in his country.

Speech by B. Dzrewieski at the 10th Plenary Assembly of the Conference of Allied Ministers for Education in London on November 16, 1946

In particular, he is invited to give lectures on education throughout the Kingdom. On this occasion he wrote a long article in the English magazine New Era of the International League of New Education on Schools in Poland before the war.

In 1945, he was appointed Cultural Attaché of the Polish Embassy in London, which means he followed the line of his political leader, Stanisław Mikołajczyk (successor of Raczkiewicz after his death in a plane crash in 1943). who agrees to return to Poland to unite with the Polish National Liberation Committee or "Lublin Committee", the provisional governmental body formed on 23 July 1944 on the initiative of the Soviet Union. A dissident Polish government continues to exist at the same time , but the United States and Great Britain withdraw its approval on July 6, 1945, and they must evacuate the Polish Embassy from Portland Place. Most of its members, unable to return safely to communist Poland, settled in other countries.

It was therefore as a cultural attaché that Drzewieski was appointed member of the Polish delegation to the November 1945 conference which preceded the Preparatory Commission for Unesco, of which he would later become Vice-President.

@UNESCO, Ellen Wilkinson, Minister of Education of Great Britain, reading the UNESCO Constitutive Act aloud at the 1945 conference

He made a fiery speech during which he proclaimed in the name of the European continent his pride of being poor, a poverty due to the refusal to submit to the laws of fascism and made himself the apostle of the needs for educational reconstruction:

Our schools - he says - are homeless, our teachers are failing because they are hungry and exhausted. Of course, we hear people say, "Listen, we can not get money." I am a teacher myself and I know that far too many people who do not know anything about education are discussing education. We teachers do not see enough people to discuss with equal enthusiasm a salary increase, or an improvement in the social status of teachers, or how to build good schools for our children and establish a democratic education system. But, believe me, you can get money.

He cites as an example the initiative undertaken by British children who, under the auspices of the Council for Education for Global Citizenship, would have managed to gather in less than a year with their pocket money the sum of five thousand books to help their distressed counterparts on the continent.

On October 16, 1946, he received a letter from Julian Huxley, the Executive Secretary of Unesco House, located at 19 Avenue Kleber in Paris, proposing that he join the reconstruction section of the same commission; offers that it is obliged to postpone temporarily, given its role as representative of the Polish government, until the holding of the first general conference of 16 November 1946 in London which officially gives birth to Unesco.

Stamp issued on the occasion of the first UNESCO Conference in Paris in 1946

However, he agrees to start informal contacts with the various bodies involved in the reconstruction. At the general conference, Drzewieski represents both the Polish delegation and is rapporteur at the first session of the commission for the reconstitution of education, art and culture. It defines the role of Unesco in the following way: it is responsible for stimulating both the relief provided by governmental and non-governmental agencies of donor countries as well as the production of educational supplies and equipment. ; it is even envisaged that it can undertake and finance certain projects itself.

A few days later, during the meeting held in Paris at Unesco House, 19 Avenue Kleber on November 25, 1946, he was elected president of this commission and declared that from now on he would cease to represent his country to be as the representative of the Unesco Conference. He stressed the coordinating role that Unesco could play between governmental organizations and private non-governmental organizations. A discussion then begins as to whether it should be a clearing house for information and propaganda, but also for receiving and distributing money and materials for aid to devastated countries, or a mere liaison between organizations, works, universities, schools.

Unesco in the walls of the Majestic Hotel, Paris (Unesco photo)

He held this position until January 1947, when he officially joined the Unesco Secretariat as Head of the Department of Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of the Education System. On his job description, he says he speaks fluent Polish and Russian, although French, Italian and English, correctly German. He moved to Paris at 44 rue Hamelin in the 16th arrondissement, although he made many tours abroad. For the year 1947 alone, he traveled to the United States from 25 February to 8 April, to Switzerland from 5 to 16 July, to Czechoslovakia and Poland from 7 August to 11 September, and again to the United States from December 7th to 17th.

Excerpt from B. Dzrewieski's Confidential Mission Report for Poland, August 7 to September 11, 1947

These journeys consist primarily of establishing diplomatic relations: to see how governments perceive Unesco and whether a national commission exists; explain the purpose of the latter; contact schools and their administrators, groups of teachers, publishers and distributors of educational books and various national or international self-help organizations such as the International Bureau of Education, CIER (American Commission for Rebuilding) the International Children's Fund , UNRRA, UIPE, to better coordinate fundraising or school materials; or, in devastated countries, assess the needs in terms of rebuilding schools and helping teachers. It was also during these trips that he visited not only the reconstruction camps, of which he admired the phenomenon of solidarity and international understanding , but also successively the Pestalozzi children's village of Trogen, which he described as the most astonishing and inspiring. business of post-war Europe.

Drzewieski points out the difficulty of such an undertaking when it comes to bringing together Polish children and German children, but optimistically asserts that the organizers are well prepared to provoke these encounters between children of former enemy countries by showing them for example, photos of cities in ruins in their respective countries , in order to awaken in them a community of suffering and experiences. He emphasizes the need to provide the founders of the village with substantial assistance , so that they can build more houses to accommodate another two hundred children and thus become an "experimental laboratory" for the establishment of other international villages in the area. 'other countries. Following a suggestion by the organizers of Trogen who would like Unesco to have some sort of patronage, Drzewieski proposes to organize as soon as possible a conference, under the auspices of his department, bringing together the leaders of different villages of children. which , it seems , already exist in several countries such as Germany, Denmark, France, Hungary, Poland, to reflect on a general pattern for this movement.

The following month, he notes with satisfaction that such is indeed the case in his own country in which he finally has the opportunity to return. He visits the village of Otwook, where 600 children are housed in a former sanatorium near Warsaw, also financed by the Swiss Don. According to him, such a concentration of homeless children rests on the question of the educational orientation that must be offered to them and the urgency of organizing as soon as possible a debate about a possible program to be built in the spirit or not. from Trogen.

Moreover, in order to meet the first objective of coordinating the collection activities carried out by the various non-governmental organizations, Drzewieski organizes three meetings which end up giving birth, during the last one which takes place in Paris on 23-24 September 1947 at the Unesco House, at the International Temporary Council for the Rehabilitation of Education (Ticer).

Unesco Archives 361.9 A 01

If he presides over this meeting, he wishes to mark the difference between his section of reconstruction and the new private status coordinating body thus created and withdraws from the elected board of directors after having given the final chairmanship to George E. Haynes , president of the international conference of the social service. However, he continues to provide the secretariat.

If during his presentation of the work undertaken by his service in 1947, Drzewieski announced his visit to the village Pestalozzi, he insists especially on the task of educational reconstruction in the field of education that he believes must lead urgently Ticer he thus mentions the situation in Poland and Czechoslovakia, where he has seen eleven different classes operate on a rotating basis in a single room, and for this reason have been obliged to abolish classes in music, singing, physical education and drawing, or There are also courses in cellars, schools with roofs destroyed or ancient mass graves used as playgrounds for children.

At the second session of the Unesco General Conference in Mexico City on 17 November 1947, Drzewieski resumed the idea of collecting precise information on successful experiences in the rehabilitation of children during the war and asked that the Provides support to international children's villages, which it says are "a new and growing initiative"; he proposes again to convene a conference of leaders of these villages to "study ways of integrating them into the official education system of the different countries" .

Just after the Mexico City conference and throughout the first half of 1948, Drzewieski became one of the masters of the convocation of children's village directors and several experts who Trogen on 4-18 July.

Arrival of the first delegates, including Bernard Drzewieski (3rd from right) in Trogen in July 1948

Bernard Drzewieski and Carleton Washburne at the Trogen Conference in July 1948

These experiences thus become for him an important axis of educational reconstruction, as shown by the introduction of this theme of children's villages through him in Ticer's resolutions and plans of action from March 1948. Although he was called to order by his supervisory ministry, who informed him in 1949 that the free leave granted by Foreign Affairs was coming to an end and that he had to return to a position in the latter, Bernard Drzewieski decided to stay in function at Unesco. In this capacity, he participates in many events organized by FICE, such as international youth camps.

Visit of Bernard Dzrewieski during the Second International Children's Camp at Château de Sanem (Luxembourg), 1950

Visit of Bernard Dzrewieski during the Second International Children's Camp at Sanem Castle in July 1950

Once his first contract is over in the rebuilding department, he is recruited as a program specialist for the Education Department on the subject of education for international understanding , and as special advisor to the section " education for living in a global community.

Bernard Drzewieski (1st on the left) at the FICE Congress in Florence in March 1952

He died at this post in Paris, August 13, 1953, his funeral taking place on Saturday, August 18 in the strictest intimacy.

Bernard Dzrewieski's grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery

His Wanda wife who has always been at his side as a "housewife" and faithful secretary without attribution, finds herself in great economic difficulty given the meager pension she receives on the death of her husband, housed first by colleagues of the latter, she finally left Paris to return to Poland in 1956 thanks to exceptional aid from Unesco.

Sources

Unesco Archives, Paris:

• Staff file of B. Dzrewieski. Box 106 PER / REC.1 / 106, 1965

• X07.83 Missions of B. Dzrewieski.

• 371.95 A 06 (494) "48". Conference on War Handicapped Children (Trogen 5-10 / VII / 48).

Archives of the Institute of Education in London

• dossier on the Polish section of the New Education Fellowship, WEF / A / II / 144

Bibliography

Boussion (Samuel), Gardet (Mathias), Ruchat (Martine), "Bringing everyone to Trogen: Unesco and the Promotion of an International Model of Children's Communities after World War II", Duedhal (Poul) (eds.), A History of Unesco.Global Actions and Impacts , London, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016, p. 99-115.

Unesco, The Book of Needs of Fifteen War-Devastated Countries in Education, Science and Culture , c. 1, Paris, Unesco, 1947, 111 p.