by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/3/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

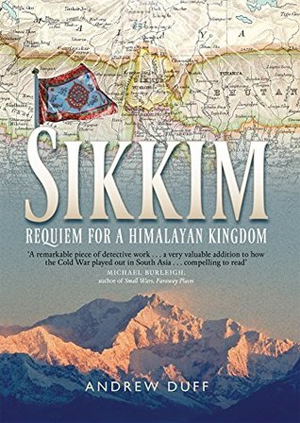

TIBETAN REFUGEES

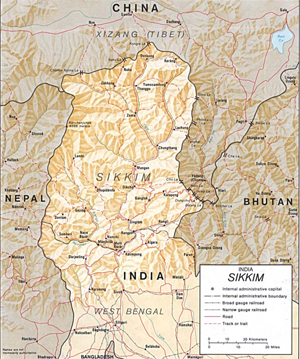

Sir. – Recent devastating events in Tibet caused over 15,000 Tibetans to cross the perilous Himalayas into India. It may be a long time before these unfortunate people can safely return to their overrun country. Our own consciences should allow us neither to neglect nor forget them.

The Indian Government has manfully coped with this addition to its own problems at home. In this country we are bound in honour to help relieve needs of the Tibetan refugees, because from 1905 to 1947 there was a special relationship between Tibet and the United Kingdom – a relationship handed on to the new India.

On balance we think it wisest to concentrate chiefly on collecting money which can be used for the benefit of the refugees, not least in the purchase of necessary antibiotics and other medicaments. The Tibet Society has opened a Tibet Relief Fund for which we now appeal in the hope of a generous response. Donations should be sent to the address below or direct to the National Bank Ltd. (Belgravia Branch), 21 Grosvenor Gardens, S.W.I.

Yours faithfully,

... Peter Fleming ... The Tibet Relief Fund, 58 Eccleston Square, S.W. I., Letter to the Times, July 31, 1959, p.7.

-- Tibet Society, by tibetsociety.com

Annex C

Excerpt from Master of Deception, The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming

by Alan Ogden

2019

Annex C

Staff List - GSI (d) / D. Division / Force 456

Officer commanding GSI (d)

Colonel Peter Fleming

Officers commanding D. Division

Colonel Peter Fleming (from November 1943)

Colonel Sir Ronald Wingate Bt. (from 25 April 1945)

Officer commanding Force 456 (from 25 April 1945)

Colonel Peter Fleming

Policy and Plans HQ SEAC Kandy

Wing Commander The Hon. Mervyn Horder, RAFVR

Lieutenant Commander the Earl of Antrim, RNVR5 [Posted SACSEA 14 November 1944.]

Captain Saunders

D. Division Rear HQ Delhi

Commander Alan Robertson-Macdonald RN, Eastern Fleet Representative

Major Peter Thorne, Grenadier Guards

Major Lucas J. Ralli, Royal Signals, GSO 2 Wireless Comms

Major A.D.R. Wilson

Captain the Hon. A.J.A Wavell

Navy Lieutenant Pei, Chinese LO

Operations Section

Lieutenant Colonel A.G. 'Johnnie' Johnson, RA6 [He does not show up on 1944/45 Indian Army Intelligence Directorate List. Holt says he came across from A Force.]

Major Gordon Rennie

Captain K.L. Campbell (from 12 March 1945)

Captain J.N. Carleton-Stiff, R.Sigs.

Technical Section

Major C.H. Starck, RE

Captain J.A. Gloag, (Z Force from 15 March 1945)

Captain G.T.H. Carter, RE (from 2 April 1945)

Captain D.W. Timmis

Captain Skipworth

Tac HQ Calcutta (Advanced HQ ALFSEA)

Lieutenant Colonel 'Frankie' Wilson, GSO 1

Major J.M. Howson (from 30 March 1945)

Major J.C.W. Napier-Munn, RA

Major R.A. Gwyn, Base Signal Office Calcutta

Squadron Leader J. King7 [Does not show on 1945 RAF List (India).]

Captain 'Jack' Corbett (US) March 1945

Control Section

Major S.C.F. Pierson, GSO 2

D Force

Force HQ

Lieutenant Colonel P.E.X Tumbull -- Commanding officer

Major E.F.A 'Ted' Royds -- 2 i/c

Major J.C. Gladman8 [Keen collector of butterflies of the Arakan coast!] - Officer i/c Sonic

Captain K.A.J. Booth -- Adjutant

Captain P.R. Hedges -- 2 i/c Sonic

Lieutenant M.W. Trennery -- i/c Sonic training

Lieutenant B.E. Chambers -- i/c Sonic training

Companies

Captain G. Morgan -- OC 51 Coy

Lieutenant E.H. Morris, RE -- 2 i/c 51 Coy

Captain J.A. Fosbury -- OC 52 Coy

Captain C.A.R. Richardson -- OC 53 Coy

Lieutenant R.A. Spark -- 2 i/c 53 Coy

Captain J.I. Nicolson, KAR Reserve of Officers -- OC 54 Coy

Lieutenant R.H. Walton, RA -- 2 i/c 54 Coy

Lieutenant G.H. Smith -- i/c Sonic 54 Coy

Captain G.W. Boyd -- OC 55 Coy

Lieutenant J.D. Taylor -- 2 i/c 55 Coy

Captain C.J.C. Lumsden -- OC 56 Coy

Lieutenant J.H. Atkinson -- i/c Sonic 56 Coy

Captain D.W. Timmis -- OC 57 Coy

Captain R.H.D. Norman -- OC 58 Coy

Lieutenant B. Raymond -- 2 i/c 58 Coy

Lieutenant J.G. Sommerville -- i/c Sonic 58 Coy

No.1 Naval Scout Unit

Lieutenant Commander H.B. Brassey, RNVR

ITB

Colonel Reginald Bicat

Chief Clerk: Sergeant Ashley

Major N.P. Dawnay

Major J.A. Denney

Major H.L. Frenkel

Major D.W. Gaylor

Major J.F. Howarth

Major D.K. Kerker

Major J.L. Schofield

Major J.E. Vaughan

Captain H.N. Barker

Captain R. Baxter

Captain A. Forbes

Captain D.H. Pickhard

Captain B.K.H. Richards

Captain E.G. Sperring

Captain A.H.D. Williams

Liaison officers with Army Formations

Eastern Army (1943): Colonel 'Fookiform' Foulkes and Major Frankie Wilson

HQ Fourteenth Army: Major John Warde-Aldham

NCAC: Captain Jack Corbett (US). Appointed February 1945

IV Corps: Major J.M. Howson

XV Corps: Major D. Graham, MC

XXXIII Corps: Major R. Campbell GSO 2

Control Section China Chungking

Major S.C.F. Pierson

Lieutenant Colonel F.G. Bishop

Peter Fleming

OBE DL

Born Robert Peter Fleming

31 May 1907

Mayfair, London, England

Died 18 August 1971 (aged 64)

Black Mount, Argyllshire, Scotland[1]

Resting place St. Bartholomew's Churchyard, Nettlebed

Education Eton College

Alma mater Christ Church, Oxford

Occupation Writer, adventurer

Spouse(s) Celia Johnson (m. 1935)

Children 3

Relatives Ian Fleming (brother)

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Peter Fleming OBE DL (31 May 1907 – 18 August 1971) was a British adventurer, soldier and travel writer.[2] He was the elder brother of Ian Fleming,[3] creator of James Bond.

Lord Rothermere succeeded his father in the viscountcy in 1940. He married three times and had four children ....

He married, secondly, Ann Geraldine Mary Charteris, widow of Shane Edward Robert O'Neill, 3rd Baron O'Neill, who was killed in action in 1944 in Italy. She also was the daughter of Captain Hon. Guy Lawrence Charteris and Frances Lucy Tennant and granddaughter of Hugo Richard Charteris, 11th Earl of Wemyss, on 28 June 1945 (divorced 1952). Ann Charteris then married the writer Ian Fleming in 1952.[3]

-- Esmond Harmsworth, 2nd Viscount Rothermere, by Wikipedia

Early life

Peter Fleming was one of four sons of the barrister and MP Valentine Fleming, who was killed in action in 1917, having served as MP for Henley from 1910. Fleming was educated at Eton, where he edited the Eton College Chronicle. The Peter Fleming Owl (the English meaning of "Strix", the name under which he later wrote for The Spectator) is still awarded every year to the best contributor to the Chronicle.[4] He went on from Eton to Christ Church, Oxford, and graduated with a first-class degree in English.

Fleming was a member of the Bullingdon Club during his time at Oxford.[5] On 10 December 1935 he married the actress Celia Johnson (1908–1982), best known for her roles in the films Brief Encounter and The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.[6]

Travels

In Brazil

In April 1932 Fleming replied to an advertisement in the personal columns of The Times: "Exploring and sporting expedition, under experienced guidance, leaving England June to explore rivers central Brazil, if possible ascertain fate Colonel Percy Fawcett; abundant game, big and small; exceptional fishing; room two more guns; highest references expected and given." He then joined the expedition, organised by Robert Churchward, to São Paulo, then overland to the rivers Araguaia and Tapirapé, heading towards the last-known position of the Fawcett expedition.

During the inward journey the expedition was riven by increasing disagreements as to its objectives and plans, centred particularly on its local leader, whom Fleming disguised as "Major Pingle" when he wrote about the expedition. Fleming and Roger Pettiward (a school and university friend recruited onto the expedition as a result of a chance encounter with Fleming) led a breakaway group.

This group continued for several days up the Tapirapé to São Domingo, from where Fleming, Pettiward, Neville Priestley and one of the Brazilians hired by the expedition set out to find evidence of Fawcett's fate on their own. After acquiring two Tapirapé guides the party began a march to the area where Fawcett was reported to have last been seen. They made slow progress for several days, losing the Indian guides and Neville to foot infection, before admitting defeat.

The expedition's return journey was made down the River Araguaia to Belém. It became a closely fought race between Fleming's party and "Major Pingle", the prize being to be the first to report home, and thus to gain the upper hand in the battles over blame and finances that were to come. Fleming's party narrowly won. The expedition returned to England in November 1932.

Fleming's book about the expedition, Brazilian Adventure, has sold well ever since it was first published in 1933, and is still in print.

In Asia

Fleming travelled from Moscow to Peking via the Caucasus, the Caspian, Samarkand, Tashkent, the Turksib Railway and the Trans-Siberian Railway to Peking as a special correspondent of The Times. His experiences were written up in One's Company (1934). He then went overland in company of Ella Maillart from China via Tunganistan to India on a journey written up in News from Tartary (1936). These two books were combined as Travels in Tartary: One's Company and News from Tartary (1941). All three volumes were published by Jonathan Cape.

According to Nicolas Clifford, for Fleming China “had the aspect of a comic opera land whose quirks and oddities became grist for the writer, rather than deserving any respect or sympathy in themselves”.[7] In One's Company, for example, Fleming reports that Beijing was “lacking in charm”, Harbin was a city of “no easily definable character”. Changchun was “entirely characterless”, and Shenyang was “non-descript and suburban". However, Fleming also provides insights into Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state in Manchuria, which helped contemporary readers to understand Chinese resentment and resistance, and the aftermath of the Kumul Rebellion. In the course of these travels Fleming met and interviewed many prominent figures in Central Asia and China, including the Chinese Muslim General Ma Hushan, the Chinese Muslim Taoyin of Kashgar, Ma Shaowu, and Pu Yi.

Of Travels in Tartary, Owen Lattimore remarked that Fleming, who "passes for an easy-going amateur, is in fact an inspired amateur whose quick appreciation, especially of people, and original turn of phrase, echoing P. G. Wodehouse in only a very distant and cultured way, have created a unique kind of travel book". Lattimore added that it "is only in the political news from Tartary that there is a disappointment," as, in his view, Fleming offers "a simplified explanation, in terms of Red intrigue and Bolshevik villains, which does not make sense."[8]

Stuart Stevens retraced Peter Fleming's route and wrote his own travel book.[9]

World War II

Just before war was declared, Peter Fleming, then a reserve officer in the Grenadier Guards, was recruited by the War Office research section investigating the potential of irregular warfare (MIR). His initial task was to develop ideas to assist the Chinese guerrillas fighting the Japanese. He served in the Norwegian campaign with the prototype commando units – Independent Companies – but in May 1940 he was tasked with research into the potential use of the new Local Defence Volunteers (later the Home Guard) as guerrilla troops. His ideas were first incorporated into General Thorne's XII Corps Observation Unit, forerunner of the GHQ Auxiliary Units. Fleming recruited his brother, Richard, then serving in the Faroe Islands, to provide a core of Lovat Scout instructors to his teams of LDV volunteers.

When Colin Gubbins was appointed to head the new Auxiliary Units, he incorporated many of Peter's ideas, which aimed to create secret commando teams of Home Guard in the coastal districts most liable to the risk of invasion. Their role was to launch sabotage raids on the flanks and rear of any invading army, in support of regular troops, but they were never intended as a post-occupation 'resistance' force, having a life expectancy of only two weeks.[10]

Peter Fleming later served in Greece, but his principal service, from 1942 to the end of the war, was as head of D Division,[11] in charge of military deception operations in Southeast Asia, based in New Delhi, India.

Fleming was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the 1945 Birthday Honours and in 1948 he was awarded the Order of the Cloud and Banner with Special Rosette by the Republic of China.[12][13]

Later life

After the war Peter Fleming retired to squiredom at Nettlebed, Oxfordshire and was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant for Oxfordshire on 31 July 1970.[14]

Death

Fleming died on 18 August 1971 from a heart attack while on a shooting expedition near Glen Coe in Scotland. His body was buried in Nettlebed Churchyard, where a stained glass window was later installed in the church dedicated to his memory.[15] The gravestone reads:

He travelled widely in far places;

Wrote, and was widely read.

Soldiered, saw some of danger's faces,

Came home to Nettlebed.

The squire lies here, his journeys ended –

Dust, and a name on a stone –

Content, amid the lands he tended,

To keep this rendezvous alone.

Family

After the death of his brother Ian, Peter Fleming served on the board of Glidrose, Ltd, the company purchased by Ian to hold the literary rights to his professional writing, particularly the James Bond novels and short stories. Peter also tried to become a substitute father for Ian's surviving son, Caspar, who overdosed on narcotics in his twenties.

Peter and Celia Fleming remained married until his death in 1971. He was survived by their three children:

• Nicholas Peter Val Fleming (1939–1995), writer and squire of Nettlebed. He deposited Peter Fleming's papers for public access at the University of Reading in 1975. These include several unpublished works, as well as the manuscripts of several of his books that are now out of print. Nichol Fleming's partner for many years was the merchant banker Christopher Roxburghe Balfour (b. 1941), brother of Neil Balfour, second husband (1969–78) of Princess Jelizaveta of Yugoslavia. Nettlebed is now jointly owned by his sisters.

• (Roberta) Katherine Fleming (b. 1946), writer and publisher, is now Kate Grimond, wife of Johnny Grimond, foreign editor of The Economist. Johnny is the elder surviving son of the late British Liberal Party leader Jo Grimond, and grandson maternally of Violet Bonham-Carter, herself daughter of the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith. Kate and John have three children, Jessie (a journalist), Rose (an actress turned organic foods entrepreneur) and Georgia (a journalist at The Economist online).

• Lucy Fleming (born 1947), now Lucy Williams, is an actress. In the 1970s she starred as Jenny in the BBC's apocalyptic fiction series Survivors. She was first married in 1971 to Joseph "Joe" Laycock (d. 1980), son of a family friend Robert Laycock and his wife Angela Dudley Ward, and was on honeymoon at the time of her father's sudden death in Argyllshire. Lucy and Joe had two sons and a daughter, Flora. Flora and her father, Joe, were drowned in a boating accident in 1980. At the time of their deaths Lucy and Joe were separated on good terms. Lucy later married the actor and writer Simon Williams. Her sons are Diggory and Robert Laycock.

Peter Fleming was the godfather of the British author and journalist Duff Hart-Davis, who wrote Peter Fleming: A Biography (published by Jonathan Cape in 1974). Duff's father Rupert Hart-Davis, a publisher, was good friends with Peter, who gave him a home on the Nettlebed estate for many years and gave financial backing to his publishing ventures.

Legacy

The Peter Fleming Award, worth £9,000, is given by the Royal Geographical Society for a "research project that seeks to advance geographical science".[16]

Fleming's book about the British military expedition to Tibet in 1903 to 1904 is credited in the Chinese film Red River Valley (1997).

Quotations

• "São Paulo is like Reading, only much farther away." – Brazilian Adventure

• "Public opinion in England is sharply divided on the subject of Russia. On the one hand you have the crusty majority, who believe it to be a hell on earth; on the other you have the half-baked minority who believe it to be a terrestrial paradise in the making. Both cling to their opinions with the tenacity, respectively, of the die-hard and the fanatic. Both are hopelessly wrong." – One's Company

• The recorded history of Chinese civilisation covers a period of four thousand years.

The Population of China is estimated at 450 million.

China is larger than Europe.

The author of this book is twenty-six years old.

He has spent, altogether, about seven months in China.

He does not speak Chinese.

Preface, One's Company

Fleming's works

Fleming was a special correspondent for The Times and often wrote under the pen-name "Strix" (Latin for "screech owl") an essayist for The Spectator.

Non-fiction

• 1933 Brazilian Adventure – Exploring the Brazilian jungle in search of the lost Colonel Percy Fawcett.

• 1934 One's Company: A Journey to China in 1933 – Travels through the USSR, Manchuria and China. Later reissued as half of Travels in Tartary.

• 1936 News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir – Journey from Peking to Srinagar via Sinkiang. He was accompanied on this journey by Ella Maillart (Kini). Later reissued as half of Travels in Tartary.

• 1952 A Forgotten Journey – A diary Fleming kept during a journey through Russia and Manchuria in 1934. Reprinted as To Peking: A Forgotten Journey from Moscow to Manchuria (2009, ISBN 978-1-84511-996-6)

• 1953 Introduction to Seven Years in Tibet by Heinrich Harrer published by Rupert Hart-Davis, London[17]

• 1955 Tibetan Marches – A translation from French of Caravane vers Bouddha by André Migot

• 1956 My Aunt's Rhinoceros: And Other Reflections — A collection of essays written (as "Strix") for The Spectator.

• 1957 Invasion 1940 — an account of the planned Nazi invasion of Britain and British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War. Published in the United States as Operation Sea Lion

• 1957 With the Guards to Mexico: And Other Excursions — A collection of essays written for The Spectator.

• 1958 The Gower Street Poltergeist — A collection of essays written for The Spectator.

• 1959 The Siege at Peking — An account of the Boxer Rebellion and the European-led siege of the Imperial capital.

• 1961 Bayonets to Lhasa: The First Full Account of the British Invasion of Tibet in 1904

• 1961 Goodbye to the Bombay Bowler — A collection of essays written for The Spectator as 'Strix'.

• 1963 The Fate of Admiral Kolchak — a study of the White Army leader Admiral Kolchak who attempted to save the Imperial Russian family at Ekaterinburg in 1918.

Fiction[edit]

Books

• 1940 The Flying Visit – A humorous novel about an unintended visit to Britain by Adolf Hitler. Illustrated by David Low.

• 1942 A Story to Tell: And Other Tales — A collection of short stories.

• 1952 The Sixth Column: A Singular Tale of Our Times

• The Sett (unfinished, unpublished)[18]

Short fiction

• "The Kill" (1931)[19]

• "Felipe" (1937)[20]

References[edit]

Notes

1. "Peter Fleming, 64, a British writer". New York Times. Special to the New York Times. 20 August 1971. p. 36.

2. "Obituary Colonel Peter Fleming, Author and explorer". The Times, 20 August 1971 p14 column F.

3. "Authors". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

4. "Captain Peter Fleming". http://www.coleshillhouse.com. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

5. "Expedition Fleming: Writer, Traveller, Soldier, Spy". Artistic Licence Renewed. 5 October 2017. Retrieved 13 May2019.

6. "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31289.

7. Nicholas J. Clifford. "A Truthful Impression of the Country": British and American Travel Writing in China, 1880–1949.Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001. pp. 132–33

8. Pacific Affairs 9.4 (1936): 605–606 [1]

9. Stuart Stevens (1988). Night Train to Turkistan: Modern Adventures Along China's Ancient Silk Road. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-87113-190-4.

10. Atkin, Malcolm (2015). Fighting Nazi Occupation: british Resistance 1939 – 1945. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. pp. 24, 26, 31, –2, 56–61, 66, 72, 76–7, 87, 172, 181. ISBN 978-1-47383-377-7.

11. "Captain Peter Fleming". coleshillhouse.com. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

12. "No. 37119". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 June 1945. p. 2943.

13. "No. 38288". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 May 1948. p. 2921.

14. "No. 45170". The London Gazette. 11 August 1970. p. 8872.

15. 'Grave of Capt. Peter Fleming', film of Fleming's grave, published on Youtube, 26 July 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h2Xsy3YgqlY

16. "Peter Fleming Award". Rgs.org. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

17. Harrer, Heinrich. "Seven Years in Tibet". The Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

18. Hart-Davis 1974, p. 316.

19. "Bibliography: The Kill". Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

20. "Bibliography: Felipe". Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

Cited works

• Hart-Davis, Duff (1974). Peter Fleming: A Biography. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-01028-X.

• Clifford, Nicholas J (2001). A Truthful Impression of the Country: British and American Travel Writing in China, 1880–1949. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472111973.

• La Gazette des Français du Paraguay – Peter Fleming Un Aventurier au Brésil – Peter Fleming Un Aventurero en Brasil – Numéro 5 Année 1, Asuncion Paraguay.

External links[edit]

• A short biography provided by the University of Reading

• A profile stressing his travel writing

• Peter Fleming genealogy. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

• Peter Fleming's daughters

• Source for the death date of his son Nicholas Fleming at ianfleming.org

• Peter Fleming's rook rifle – a correspondence

• Peter Fleming on IMDb

• Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers.

• Podcast talk and live blogging at the Shanghai International Book Festival with Paul French's talk on Peter Fleming

• Paul French, "Peter Fleming" [2]

• "Archival material relating to Peter Fleming". UK National Archives.

• Portraits of (Robert) Peter Fleming at the National Portrait Gallery, London

• Translated Penguin Book – at Penguin First Editions reference site of early first edition Penguin Books.

• I.B. Tauris published Fleming's To Peking: A Forgotten Journey from Moscow to Manchuria (out of stock 4/18), News from Tartary and Bayonets to Lhasa: The British Invasion of Tibet; also its A Dance with the Dragon: The Vanished World of Peking's Foreign Colony by Julia Boyd includes Fleming among its subjects.