Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

The English Sangha Trust: History

by Amaravati.org

Accessed: 9/7/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

The English Sangha Trust (EST) is the legal charitable body, originally established in 1956, that serves to steward donations given to the Sangha (monastic community). This is the body that in 1977 owned the Hampstead Vihara, which had no sangha in residence, and then invited Ajahn Sumedho to come from Thailand; thus began Ajahn Sumedho’s efforts to establish the Thai Forest tradition outside Thailand.

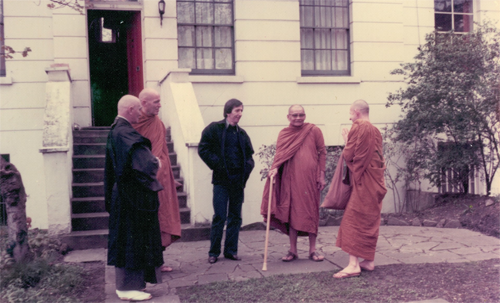

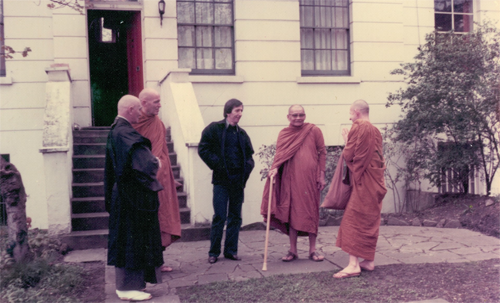

Hampstead Vihara in 1978. From L to R: visiting Roshi, Ajahn Sumedho, George Sharp, Ajahn Chah, Ajahn Kemadhammo

Once the EST had a resident sangha in Hampstead, decision-making power was vested in the sangha. Then in 1979, after a donation to the sangha of 96 acres of forest in West Sussex, the sangha decided to move to Sussex. The EST then acquired Chithurst House and sold the Hampstead Vihara. Five years later, when the burgeoning resident sangha of monks and nuns at Chithurst (Cittaviveka) needed more space, the sangha and the EST decided to purchase the site that is now Amaravati.

Listen how the Sangha came to England by George Sharp

Amaravati 1

Amaravati 30 Years, by Ajahn Amaro, Ajahn Sumedho, George Sharp Amaravati 2014

Amaravati 2

How the Sangha Came to England – Interview (Part 1 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati 3

How the Sangha Came to England – Interview (Part 2 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati 4

How the Sangha Came to England – Q and A (Part 3 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati in the 1980s. The temple & cloisters is currently where you see the empty square in the middle

Strategic priorities

To this day the EST legally owns and manages both Cittaviveka and Amaravati monasteries and its priorities remain focused on them and their resident sangha:

• to purchase land that may support the existing monastic properties;

• to maintain the supply and good order of the four requisites (shelter, food, clothing and medicinal needs) for the sangha in the two monasteries;

• developing the monasteries in terms of buildings, land and physical structures in accordance with the wishes of the resident monastics. At Amaravati this is now being implemented through a wholly-owned subsidiary called Amaravati Developments Ltd (ADL). Details can be found here.

• to facilitate such publications in any format, as are produced or approved of by the resident monastics.

Model of proposed redevelopment of Amaravati. Notice the retreat centre, Bhikku Vihara & Sala will have different shaped buildings.

Stewardship

All funds given (donated) to those two monasteries are held and managed by the EST. The legal structure of the EST is that of a Charitable Company limited by twelve shares all held by monastics. There are also up to nine lay trustees. The sangha shareholders include the Abbots of Cittaviveka and Amaravati, and monks and nuns elected by the monastics representing both monasteries. The lay trustees are chosen by the sangha, and since the monastic discipline prohibits the monks and nuns from making direct financial decisions, the lay trustees are vested with the responsibility of making final decisions over allocation of finances, in accordance with the needs and wishes of the monastics.

The EST submits statutory annual accounts and returns to Companies House and the Charity Commission for England and Wales; these can be downloaded from the respective websites. As a Company and Charity the EST is also responsible for implementing the requirements of a range of bodies on subjects from tax, insurance, health and safety, child protection, immigration and fire prevention, to re-cycling.

The following link is a leaflet given out annually with a summary of Amaravati’s current activities and plans, its running costs and information on ways to help, which could include bringing a contribution such as food, making a donation, or even offering your services in some capacity (driving, gardening, etc).

EST Annual Leaflet for Amaravati 2016-2017 – PDF

Sub-groups

The EST has a Finance Sub-Committee to advise on detailed management of its finances.

At Cittaviveka all day-to-day affairs are managed through the Cittaviveka Advisory Group (CAG).

The EST is also the steward for the Amaravati Retreat Centre.

The trustee directors

The lay trustees are all friends of the sangha who have been practising for a number of years and all have specialist skills in management, finance and related subjects. They are appointed for up to three years at a time. The current lay trustees are

• John Stevens – Chair

• Caroline Leinster – Trust Secretary

• Kazuko Kawamura

• Sudanta Abeyakoon

• Nicholas Carroll

You are welcome to contact the EST by using the form below.

by Amaravati.org

Accessed: 9/7/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

[T]he English Sangha Trust, a Buddhist organization founded by Christmas Humphreys...

-- Friends of the Western Buddhist Order: Friends, Foes, and Files, by Henry Shukman, Tricycle, Summer 1999

Luang Pu Sodh was one of the first Thai preceptors to ordain people outside Thailand as Buddhist monks. He ordained the Englishman William Purfurst (a.k.a. Richard Randall) as "Kapilavaddho" at Wat Paknam in 1954. Kapilavaddho returned to Britain to found and help lead the English Sangha Trust and English Sangha Association.27th May 1951

“Those present at the inaugural meeting were Venerable U Thittila, Mr W. Purfurst, Mr and Mrs C.J. Bartlett, Mr F. Murie, Mr J. Garry, Mr S.H. Vincent, Mr H. Jones, Miss C. [Connie] E. Waterton, Miss D. Westwell, Miss K. Knibbs.”

“This hard-working group of people under the able Secretary Miss Connie Waterton never did much shouting about their accomplishments. They showed their great worth by what their efforts produced. It was this same group, with a few friends in London, who fostered and helped the work of Venerable Kapilavaddho.

They helped create the English Sangha Trust Ltd. and also founded the English Sangha Association from their membership. Additionally, they organised the first week long course in Vipassana in England. They continued to hold these courses while the demand was there. In addition, this group created the Dāna Fund, which was used to support members in distress, maintenance of bhikkhus, and lecturer expenses. The fund was eventually handed over to the London Buddhist Society.”

-- Honour Thy Fathers: A Tribute to the Venerable Kapilavaddho ... And brief History of the Development of Theravāda Buddhism in the UK, by Terry Shine

Former director of the trust Terry Shine described Kapilavaddho as the "man who started and developed the founding of the first English Theravada Sangha in the Western world". He was the first Englishman to be ordained in Thailand, but disrobed in 1957, shortly after his mentor Phra Ṭhitavedo [Ṭhitavedo is variously spelt Thiṭavedho, Ṭhittavedho, Thiṭavaḍḍho, Thiṭavedo and Thitavedo in sources.] had a disagreement with Luang Pu Sodh and left Wat Paknam. [Accusation of financial irregularities in relation to temple funds; the formal meeting from which Kapilavaddho walked away was a disciplinary meeting in relation to Ṭhitavedo.]. He was ordained again in England under Chao Khun Sobhana, and became the director of the English Sangha Trust in 1967.

-- Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro [Luang Por Sodh] [Luang Pu Wat Paknam] [Phramongkolthepmuni] [Phra Mongkolthepmuni], by Wikipedia

16 Nov 55 Inaugural meeting of the EST [English Sangha Trust] (M-EST)

Dec 1955 On the 30th Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho returned to Thailand with Samaṇeras Vijjavaḍḍho, Saddhāvaḍḍho and Paññāvaḍḍho (MW 55/56) (14th Dec according to Ajahn Paññāvaḍḍho)

1956 M. Walshe was Vice president of The Buddhist Society (MW 55/56)

27 Jan 56 “Samaṇeras Vijjāvaḍḍho, Saddhāvaḍḍho and Paññāvaḍḍho (George Blake, Robert Albison and Peter Morgan) were ordained at Wat Paknam. Upajjhāya was Venerable Chao Khun Bhavanakasol (later Mangala-Rayamuni). The Kammavācāya was the Venerable Chao Khun Dhammavorodon (later to become Somdet — the Vice-Patriarch of Thailand). The Anusavanacaya was Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho.” (R&B). “After some time the four English bhikkhus relocated to Wat That Tong, Sukumvit Road, Bangkok” (AP)

21 Mar 56 Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho returned to England. EST [English Sangha Trust] rented Flat 9, 10 Orme Court, Bayswater, (M-EST First annual report by Directors. 30 April 57)

April 1956 Venerable Saddhavaḍḍho returned to England and shortly afterwards disrobed and returned to Rochdale. Meanwhile the Venerables Pannavaḍḍho and Vijjavaḍḍho went to Wat Vivekaram, Bang Pra village, Chonburi province to practice meditation (AP)

1 May 56 EST [English Sangha Trust] was incorporated with the following directors: Cyril John Bartlett (Chairman), Reginald Charles Howes (Secretary), Albert Ernest Allen (Treasurer), Hans Gunther Mynssen, Frederick Henry Bradbury, Ronald Joseph Browning. Mr Marcus acted as Solicitor for the Trust. Mr C. Bartlett served on both the MBS and EST [English Sangha Trust] (MW 55/56 p92) (M-EST)

June 56 Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho on hearing that Venerable Vijjavaḍḍho was ill, returned to Thailand (AP)

16 July 56 The Venerables Kapilavaḍḍho, Paññavaḍḍho and Vijjavaḍḍho return to England (AP)

Aug 1956 Venerable Vijjavaḍḍho disrobed, he married and is at present living in Canada (AP)

Aug 1956 Two German brothers and Miss Lisa Schroeder requested to come to England to become samaṇeras and upasika (M-EST)

Aug 1956 “The English Sangha Association is a new formation. It was founded at Oxford on 11/18 August 1956 by a group of sixteen people who had just completed a strenuous and continuous course in the practice of samadhi (concentration) and vipassana (insight) lasting a week under instruction of the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho.” (MW Nov 56) (M-EST First annual report by Dir. 30 April 57)

Sept 1956 Venerable Paññavaḍḍho went to stay in Manchester (AP)

Sept 1956 On the 14th Mr Walshe became a director of the EST [English Sangha Trust], Mr Browning, a founding director of the EST [English Sangha Trust] resigned (M-EST)

10 Oct 56 Buddhist Society moves to 58 Eccleston Sq (MW-55/56) (CH p59)

Oct 1956 EST [English Sangha Trust] leased 50 Alexandra Rd, London N.W.8. (M-EST First annual report by Dir. 30 April 57)

Dec 1956 First Sangha Magazine produced (S Dec 56)

1957 Dr (philosophy) Lisa Schroeder became Upāsikā Cintavāsī (5th Feb) (A)

She arrived approximately Jan 57 (M-EST Feb 57)

Feb 1957 Venerable Paññāvaḍḍho in charge of the Buddhist Society, Manchester (MW 55/56). Venerable Paññāvaddho in Manchester (S Feb 57 p3)

Mar 1957 Venerable Paññāvaḍḍho returned to London (AP)

Mar 1957 Mr Walshe vice president and Meetings Secretary of Buddhist Society (MW 55/56)

24 Mar 57 Two German brothers, Walter and Gunther Kulbarz ordained becoming Samaṇeras Saññavaḍḍho and Sativaḍḍho

Mr Wooster requested to be a samaṇera (M-EST Mar 57)

1957 Arthur Wooster becomes Sāmaṇera Ñāṇavaḍḍho (4th May) (S May 57)

In late May or early June Venerable Paññavaḍḍho officiated at Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho’s disrobing (due to ill health). Venerable Paññavaḍḍho took over leadership of EST [English Sangha Trust] helped by the three Samaṇeras, Saññavaḍḍho, Sativaḍḍho and Naṇavaḍḍho and Upasika Cintavasi. (M-EST June 57)

June 1957 Mr Marcus became Director of EST [English Sangha Trust] (M-EST)

July 1957 Mr Bradbury, a founding director of the EST [English Sangha Trust] resigned (M-EST)

1958 Russell Williams (now 81) joined MBS (MBS)

Jan 1958 Mr Mynssen a founding director of the EST [English Sangha Trust] resigned (M-EST)

April 1958 The lease on 50 Alexandra Road was renewed (M-EST)

2 July 58 The German twin brothers Samaṇeras Saññāvaḍḍho and Sativaḍḍho were the first ever ordained on British soil in a historic ceremony at the Thai Embassy. They became Bhikkhus Dhammiko and Vimalo (MW 62/63). Apparently this ordination was not accepted in Thailand and the two bhikkhus re-ordained in Burma. Subsequently Bhikkhu Dhammiko left the Sangha for a university post (AP). “Bhikkhu Vimalo continued in the robe for many years. In approximately 1970 he wrote a Dhamma article called Awakening to the Truth recently brought to light by DFP students. See page 54 above for extract and EST [English Sangha Trust] libraries for a full copy (ED)

Jan 1959 Mr Allanm a founding director of the EST [English Sangha Trust], resigned (M-EST)

July 1959 Three bhikkhus, one sāmaṇera, and one upāsikā supported by trust (M-EST)

Sept 1959 £24,000 donated to the EST [English Sangha Trust] from Mr H. J. Newlin (M-EST)

June 60 Ānanda Bodhi (Leslie Dawson) offered to come to UK to teach (M-EST)

Eve Engle (Sister Visākhā) who gave valued assistance in the formation of the EST [English Sangha Trust] died, unfortunately drowned off the coast of Ceylon. She left a legacy of £15,000 to the EST [English Sangha Trust] (S 15 July 1960 Directors report).

Oct 1960 Connie Waterton asked the EST [English Sangha Trust] to lend her £375 to purchase the house she rented and used for the MBS meetings — agreed (MEST)

1961 Sāmaṇera Sujīvo, formerly Laurence Mills, became Bhikkhu Khantipālo in Bangalore, India (see Thai Buddhism) (S Sept 61)

12 Mar 61 John Richards became Sāmaṇera Mangalo (MW 61/62)

9 Nov 1961 Ānanda Bodhi arrives in UK from Burma (S Nov 61)

21 Nov 61 Venerable Paññāvaḍḍho to Thailand (MW 61/62) (S Nov 61)

4 Dec 1961 Bhikkhus Vimalo, Dhammiko and Sāmaṇera Maṅgalo to Burma (S Dec 61)

Dec 1961 EST [English Sangha Trust] directors reported the English Sangha Association as having expressed dissatisfaction with the Alexandra Street property regarding suitability for the monks. They agreed to find a more suitable property (S)

Feb 1962 Mr C. Bartlet and Mr R. Howes founding directors of the EST [English Sangha Trust] resigned (S Mar 62)

Mr Walshe became acting Chairman of the EST [English Sangha Trust] (M-EST)

28 Oct 62 131 Haverstock Hill was inaugurated. Mr Walshe, Chairman of EST [English Sangha Trust] (S Dec 62)

May 1963 Between February and May, Biddulph Old Hall was bought (S May and June 63)

Nov 1963 Ānanda Bodhi to Thailand

1963 129 Haverstock Hill was purchased. The property was rented to provide an income for the Vihāra

April 1964 Ānanda Bodhi returned and went to Biddulph and taught samādhi and vipassanā, Wat Paknam method. (S Mar 64)

April 1964 London Buddhist Vihāra moved from 10 Ovington Gds, Knightsbridge to 5 Heathfield Gds, Chiswick. Venerable Saddhātissa Mahāthera was the incumbent

1964 Lease of Sangha House, Alexandra Street finished

Venerable Sangharakshita [Dennis Lingwood] expected to arrive April (S Mar 64)

Jan 1965 Monks in residence at this time Bhikkhus Saṅgharakshita [Dennis Lingwood], Vimalo and Maṅgalo[1965/1966/1967] Venerable Ananda Bodhi returned to England in the Fall of 1961, at the invitation of the English Sangha Trust, becoming the Resident Teacher of the Camden Town Vihara. He was a special guest speaker at the Fifth International Congress of Psychotherapists in London, where he met Julian Huxley, Anna Freud and R.D.Laing, among others. For the next three years he taught extensively throughout the UK, founding the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara in London and the Johnstone House Contemplative Community—a retreat centre in southern Scotland. During this period he also joined a Masonic lodge. In 1965, when he decided to move to Toronto with two of his British students, Johnstone House was entrusted to Venerable Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Akong Tulku, becoming Kagyu Samye Ling—the first Vajrayana centre to be established in the West.

-- Ven. Namgyal Rinpoche [Venerable Ananda Bodhi/Leslie George Dawson], by Dharma Centre of WinnipegTo celebrate 50 years of Chogyam Trungpa's arrival in the UK Rigdzin Shikpo visited Biddulph Old Hall where he received many precious teachings from Trungpa Rinpoche.

-- A Tour of Biddulph Old Hall: Rigdzin Shikpo takes us on a tour of Biddulph Old Hall in Staffordshire, England. Biddulph Old Hall is the site of some of Trungpa Rinpoche's early teachings in the UK, by Rigdzin Shikpo

1 Aug 66 The Thai temple opened at 99 Christchurch Road, East Sheen (S-Feb 72). Venerable Chao Khun Sobhana Dammasuddhi was the first incumbent. The King and Queen of Thailand attended, as did Bhikkhu Khantipālo (A) (CH p68)

10 Jan 67 Maurice Walshe asked John Garry to manage Biddulph. He also found Richard Randall (previously Mr Purfurst and Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho) and asked him to return

May 1967 Richard Randall became director and administrator of EST [English Sangha Trust] (R&B)

John Garry became a Director of the EST [English Sangha Trust] (M-EST)

21 Oct 67 Richard Randall reordained as the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho for the second time at Wat Buddhapadīpa, East Sheen (ART)

Dec 1967 Alan James first came to Hampstead in December 1967. He became Sāmaṇera Dīpadhammo in February and Bhikkhu Dīpadhammo in May 1968 after ordaining at Wat Buddhapadīpa, East Sheen (S Jan 72)

1968 In 1968, Gerry Rollason arrived in Hampstead. Gerry who became an accomplished artist painted the life-size picture of Ajahn Chah presently hanging in the hall at Chithurst

23 Oct 68 His Highness the Venerable Somdet Phra Vanarata (Vice- Patriarch of Thailand) visited Hampstead

2 Mar 69 Gerry Rollason and Andrew Willoughby became sāmaṇeras. They were ordained by the Venerable Chao Khun Dhammasuddhi (Dhiravaṃsa) assisted by Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho Bhikkhu and four other monks. The two young Englishmen became Sāmaṇeras Sāsanapadipa and Saddhadikā (MW 69/70)

June 1969 Buddhist Path “Robes and a bowl” article by John Garry on Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho (S). John Garry was one of the founding MBS Members. He died on 28th September 1998 (ED)

27 July 69 Jim Harris became Bhikkhu Suddhiñāṇo at Wat Buddhapadīpa. Thus making three bhikkhus at Hampstead (MW 69/70)

1969 “Mr Maurice Walshe, due to pressure of University work has had to relinquish his editorship of The Buddhist Path after several years tireless and at times courageous service. The Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho will take his place and the magazine will use its old name of Sangha. The magazine will also function as the monthly official journal of Wat Dhammapadīpa (Hampstead Vihāra) and the Fellowship.” (MW 69/70)

Nov 1969 A meditation block comprising three “cells” and a shower room in the rear garden of 131 Haverstock Hill are nearly completed. In addition there is a wooden shed also used as a Kuṭi.

Biddulph Old Hall sold (S Nov 69)

-- Honour Thy Fathers: A Tribute to the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho ... And brief History of the Development of Theravāda Buddhism in the UK, by Terry Shine

The English Sangha Trust (EST) is the legal charitable body, originally established in 1956, that serves to steward donations given to the Sangha (monastic community). This is the body that in 1977 owned the Hampstead Vihara, which had no sangha in residence, and then invited Ajahn Sumedho to come from Thailand; thus began Ajahn Sumedho’s efforts to establish the Thai Forest tradition outside Thailand.

Hampstead Vihara in 1978. From L to R: visiting Roshi, Ajahn Sumedho, George Sharp, Ajahn Chah, Ajahn Kemadhammo

Once the EST had a resident sangha in Hampstead, decision-making power was vested in the sangha. Then in 1979, after a donation to the sangha of 96 acres of forest in West Sussex, the sangha decided to move to Sussex. The EST then acquired Chithurst House and sold the Hampstead Vihara. Five years later, when the burgeoning resident sangha of monks and nuns at Chithurst (Cittaviveka) needed more space, the sangha and the EST decided to purchase the site that is now Amaravati.

Listen how the Sangha came to England by George Sharp

Amaravati 1

Amaravati 30 Years, by Ajahn Amaro, Ajahn Sumedho, George Sharp Amaravati 2014

Amaravati 2

How the Sangha Came to England – Interview (Part 1 of 3), by George Sharp

[George Sharp] When Ven. Sujita asked me to give a talk about how things began, how I began here, I was really quite interested because I’ve never heard this story, actually. And I sort of visit a memory here and there, you know, when we are talking about things, discussing this or that event, but to actually go from the beginning through – I’ve never done it. And what is more, I’ve made no preparation. And I could get the dates wrong on chronology and things, but I’ll do my best.

1956 was when the English Sangha Trust was formed, principally by Bhikku Kapilavaddho, who was formerly known as – and he had two names, I don’t know why -- one was William Purfurst, and Richard Randall. I know that he had a wife whose name was Ruth Randall, and I never heard of any lady with the name Purfurst, but I do know that he was a reporter, or a journalist and photographer, and that’s basically all I know. I don’t know how he came to be interested in Buddhism, but what I’m sure is that he was a man of considerable imagination and courage, and probably a great romantic at heart, because he tried to do something truly exceptional, which was to actually form a sangha, with basically four Bhikkus, in this country, and to try to get it going.

So the original trust deed that was prepared is the same one – it was never amended – that the Bhikkus, the sangha uses today.Kapilavaddho, Ven (William Purfurst, 1906-71): Founder of English Sangha Trust. Born Hanwell, Middlesex (UK). Dissatisfied with business life, began studying psychology, philosophy, etc.; went to London (on foot) and became photographer in Fleet St.; found a teacher to instruct him in Yoga and Vedanta; developed a color printing process; took up sculpture. 1939: official war photographer, then fireman during Blitz; met U Thittila whose pupil he became; got married; finally photographer with RAF [Royal Air Force]. After war began serious Buddhist studies with U Thittila at Buddhist Society (then in Great Russell Street) covering Sutta, Vinaya, and Abhidahamma. Began lecturing on Buddhism; founded Manchester Buddhist Society 1952; adopted anagarika status (with permission of wife); later became Samanera Dhammananada under U Thittila; worked for Buddhist Society; continued lecturing and founded societies in Oxford and Cambridge; also Buddhist Summer School. Later resigned samanera status and took job in Surrey hotel as barman to raise finance to go to Thailand. 1954: received lower and higher ordinations (single ceremony) in Thailand (name based on “Kapilavatthu,” Buddha’s home town; means “he who spreads the Dhamma”); surprised Thai Sangha with his knowledge, especially of Abhidamma and Pali languages; successfully practiced intensive samatha and vipassana meditation. Returned to UK, to London Buddhist Vihara, Knightsbridge, with intention of establishing English Sangha. 1955: to Thailand with 3 British samaneras (Robert Albison, George Blake, and Peter Morgan). 1956: triple ordination at Wat Paknam under Ven. Chao Khun Bhavanakosol – the core of an English Sangha. Returned to UK; acquired house in London; English Sangha Trust founded; period of great activity. 1957: due to ill health, disrobed; changed name to Richard Randall; married Ruth Lester; remained 10 years in obscurity. 1967: returned to robe at Wat Buddhapadipa under Ven. Chao Khun Sobhana Dhammasudhi; took over Hampstead Buddhist Vihara (then renamed Wat Dhammapadipa). Again disrobed. 1971: married Jacqueline Gray [Scott].

-- The Buddhist Handbook: A Complete Guide to Buddhist Schools, Teaching, Practice, and History, by John Snelling

-- How the Sangha Came to England – Interview (Part 1 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati 3

How the Sangha Came to England – Interview (Part 2 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati 4

How the Sangha Came to England – Q and A (Part 3 of 3), by George Sharp

Amaravati in the 1980s. The temple & cloisters is currently where you see the empty square in the middle

Strategic priorities

To this day the EST legally owns and manages both Cittaviveka and Amaravati monasteries and its priorities remain focused on them and their resident sangha:

• to purchase land that may support the existing monastic properties;

• to maintain the supply and good order of the four requisites (shelter, food, clothing and medicinal needs) for the sangha in the two monasteries;

• developing the monasteries in terms of buildings, land and physical structures in accordance with the wishes of the resident monastics. At Amaravati this is now being implemented through a wholly-owned subsidiary called Amaravati Developments Ltd (ADL). Details can be found here.

• to facilitate such publications in any format, as are produced or approved of by the resident monastics.

Model of proposed redevelopment of Amaravati. Notice the retreat centre, Bhikku Vihara & Sala will have different shaped buildings.

Stewardship

All funds given (donated) to those two monasteries are held and managed by the EST. The legal structure of the EST is that of a Charitable Company limited by twelve shares all held by monastics. There are also up to nine lay trustees. The sangha shareholders include the Abbots of Cittaviveka and Amaravati, and monks and nuns elected by the monastics representing both monasteries. The lay trustees are chosen by the sangha, and since the monastic discipline prohibits the monks and nuns from making direct financial decisions, the lay trustees are vested with the responsibility of making final decisions over allocation of finances, in accordance with the needs and wishes of the monastics.

The EST submits statutory annual accounts and returns to Companies House and the Charity Commission for England and Wales; these can be downloaded from the respective websites. As a Company and Charity the EST is also responsible for implementing the requirements of a range of bodies on subjects from tax, insurance, health and safety, child protection, immigration and fire prevention, to re-cycling.

The following link is a leaflet given out annually with a summary of Amaravati’s current activities and plans, its running costs and information on ways to help, which could include bringing a contribution such as food, making a donation, or even offering your services in some capacity (driving, gardening, etc).

EST Annual Leaflet for Amaravati 2016-2017 – PDF

Sub-groups

The EST has a Finance Sub-Committee to advise on detailed management of its finances.

At Cittaviveka all day-to-day affairs are managed through the Cittaviveka Advisory Group (CAG).

The EST is also the steward for the Amaravati Retreat Centre.

The trustee directors

The lay trustees are all friends of the sangha who have been practising for a number of years and all have specialist skills in management, finance and related subjects. They are appointed for up to three years at a time. The current lay trustees are

• John Stevens – Chair

• Caroline Leinster – Trust Secretary

• Kazuko Kawamura

• Sudanta Abeyakoon

• Nicholas Carroll

You are welcome to contact the EST by using the form below.