by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/28/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

This article is about the English geneticist. For his son the anthropologist and cyberneticist, see Gregory Bateson.

In one respect civilized man differs from all other species of animal or plant in that, having prodigious and ever-increasing power over nature, he invokes these powers for the preservation and maintenance of many of the inferior and all the defective members of his species. The inferior freely multiply, and the defective, if their defects be not so grave as to lead to their detention in prisons or asylums, multiply also without restraint. Heredity being strict in its action, the consequences are in civilized countries much what they would be in the kennels of the dog breeder who continued to preserve all his puppies, good and bad; the proportion of defectives increases. The increase is so considerable that outside every great city there is a smaller town inhabited by defectives and those who wait on them. Round London we have a ring of such towns with some 30,000 inhabitants, of whom about 28,000 are defective, largely, though, of course, by no means entirely bred from previous generations of defectives. Now, it is not for us to consider practical measures. As men of science we observe natural events and deduce conclusions from them. I may perhaps be allowed to say that the remedies proposed in America, in so far as they aim at the eugenic regulation of marriage on a comprehensive scale, strike me as devised without regard to the needs either of individuals or of a modern State. Undoubtedly if they decide to breed their population of one uniform puritan gray, they can do it in a few generations; but I doubt if timid respectability will make a nation happy, and I am sure that qualities of a different sort are needed if it is to compete with more vigorous and more varied communities. Everyone must have a preliminary sympathy with the aims of eugenists both abroad and at home. Their efforts at the least are doing something to discover and spread truth as to the physiological structure of society. The spirit of such organizations, however, almost of necessity suffers from a bias toward the accepted and the ordinary, and if they had power it would go hard with many ingredients of society that could be ill-spared. I notice an ominous passage in which even Galton, the founder of eugenics, feeling perhaps some twinge of his Quaker ancestry, remarks that “as the Bohemianism in the nature of our race is destined to perish, the sooner it goes, the happier for mankind.” It is not the eugenists who will give us what Plato has called divine releases from the common ways. If some fancier with the catholicity of Shakespeare would take us in hand, well and good; but I would not trust even Shakespeares meeting as a committee. Let us remember that Beethoven’s father was an habitual drunkard and that his mother died of consumption. From the genealogy of the patriarchs also we learn, “what may very well be the truth,” that the fathers of such as dwell in tents, and of all such as handle the harp or organ, and the instructor of every artificer in brass and iron – the founders, that is to say of the arts and the sciences – came in direct descent from Cain, and not in the posterity of the irreproachable Seth, who is to us, as he probably was also in the narrow circle of his own contemporaries, what naturalists call a nomen nudum.

Genetic research will make it possible for a nation to elect by what sort of beings it will be represented not very many generations hence, much as a farmer can decide whether his byres shall be full of shorthorns or Herefords. It will be very surprising, indeed, if some nation does not make trial of this new power. They may make awful mistakes, but I think they will try.

Whether we like it or not, extraordinary and far-reaching changes in public opinion are coming to pass. Man is just beginning to know himself for what he is – a rather long-lived animal, with great powers of enjoyment, if he does not deliberately forego them. Hitherto superstition and mythical ideas of sin have predominantly controlled these powers. Mysticism will not die out; for those strange fancies knowledge is no cure; but their forms may change, and mysticism as a force for the suppression of joy is happily losing its hold on the modern world. As in the decay of earlier religions, Ushabti dolls were substituted for human victims, so telepathy, necromancy, and other harmless toys take the place of eschatology and the inculcation of a ferocious moral code. Among the civilized races in Europe we are witnessing an emancipation from traditional control in thought, in art, and in conduct which is likely to have prolonged and wonderful influences. Returning to freer or, if you will, simpler conceptions of life and death, the coming generations are determined to get more out of this world than their forefathers did. Is it, then, to be supposed that when science puts into their hand means for the alleviation of suffering immeasurable, and for making this world a happier place, that they will demur to using those powers? The intenser struggle between communities is only now beginning, and with the approaching exhaustion of that capital of energy stored in the earth before man began it must soon become still more fierce. In England some of our great-grandchildren will see the end of the easily accessible coal, and, failing some miraculous discovery of available energy, a wholesale reduction in population. There are races who have shown themselves able at a word to throw off all tradition and take into their service every power that science has yet offered them. Can we expect that they, when they see how to rid themselves of the ever-increasing weight of a defective population, will hesitate? The time can not be far distant when both individuals and communities will begin to think in terms of biological fact, and it behooves those who lead scientific thought carefully to consider whither action should lead. At present I ask you merely to observe the facts. The powers of science to preserve the defective are now enormous. Every year these powers increase. This course of action must read a limit. To the deliberate intervention of civilization for the preservation of inferior strains there must sooner or later come an end, and before long nations will realize the responsibility they have assumed in multiplying these “cankers of a calm world and a long peace.”

The definitely feeble-minded we may with propriety restrain, as we are beginning to do even in England, and we may safely prevent unions in which both parties are defective, for the evidence shows that as a rule such marriages, though often prolific, commonly produce no normal children at all. The union of such social vermin we should no more permit than we would allow parasites to breed on our own bodies. Further than that in restraint of marriage we ought not to go, at least not yet. Something, too, may be done by a reform of medical ethics. Medical students are taught that it is their duty to prolong life at whatever cost in suffering. This may have been right when diagnosis was uncertain and interference usually of small effect, but deliberately to interfere now for the preservation of an infant so gravely diseased that it can never be happy or come to any good is very like wanton cruelty. In private few men defend such interference. Most who have seen these cases lingering on agree that the system is deplorable, but ask where can any line be drawn. The biologist would reply that in all ages such decisions have been made by civilized communities with fair success both in regard to crime and in the closely analogous case of lunacy. The real reason why these things are done is because the world collectively cherishes occult views of the nature of life, because the facts are realized by few, and because between the legal mind – to which society has become accustomed to defer – and the seeing eye, there is such physiological antithesis that hardly can they be combined in the same body. So soon as scientific knowledge becomes common property, views more reasonable and, I may add, more humane, are likely to prevail.

To all these great biological problems that modern society must sooner or later face there are many aspects besides the obvious ones. Infant mortality we are asked to lament without the slightest thought of what the world would be like if the majority of these infants were to survive. The decline in the birth rate in countries already overpopulated is often deplored, and we are told that a nation in which population is not rapidly increasing must be in a decline. The slightest acquaintance with biology, or even schoolboy natural history, shows that this inference may be entirely wrong, and that before such a question can be decided in one way or the other hosts of considerations must be taken into account. In normal stable conditions population is stationary. The laity never appreciates what is so clear to a biologist, that the last century and a quarter corresponding with the great rise in population has been an altogether exceptional period. To our species this period has been what its early years in Australia were to the rabbit. The exploitation of energy capital of the earth in coal, development of the new countries, and the consequent pouring of food into Europe, the application of antiseptics, these are the things that have enabled the human population to increase. I do not doubt that if population were more evenly spread over the earth it might increase very much more, but the essential fact is that under any stable conditions a limit must be reached. A pair of wrens will bring off a dozen young every year, but each year you will find the same number of pairs in your garden. In England the limit beyond which under present conditions of distribution increase of population is a source of suffering rather than of happiness had been reached already. Younger communities living in territories largely vacant are very probably right in desiring and encouraging more population. Increase may, for some temporary reason, be essential to their prosperity. But those who live, as I do, among thousands of creatures in a state of semistarvation will realize that too few is better than too many, and will acknowledge the wisdom of Ecclesiasticus who said, “Desire not a multitude of unprofitable children.”

But at least it is often urged that the decline in the birth rate of the intelligent and successful sections of the population (I am speaking of the older communities) is to be regretted. Even this can not be granted without qualification. As the biologist knows, differentiation is indispensable to progress. If population were homogeneous civilization would stop. In every army the officers must be comparatively few. Consequently, if the upper strata of the community produce more children than will recruit their numbers some must fall into the lower strata and increase the pressure there. Statisticians tell us that an average of four children under present conditions is sufficient to keep the number constant, and as the expectation of life is steadily improving we may perhaps contemplate some diminution of that number without alarm.

In the study of history biological treatment is only beginning to be applied....

Such a problem is raised in a striking form by the population of modern Greece, and especially of Athens. The racial characteristics of the Athenian and of the fifth century B.C. are vividly described by Galton in “Hereditary Genius.” The fact that in that period a population, numbering many thousands, should have existed, capable of following the great plays at a first hearing, reveling in subtleties of speech, and thrilling with passionate delight in beautiful things, is physiologically a most singular phenomenon. On the basis of the number of illustrious men produced by that age Galton estimated the average intelligence as at least two of his degrees above our own, differing from us as much as we do from the Negro. A few generations later the display was over. The origin of that constellation of human genius which then blazed out is as yet beyond all biological analysis, but I think we are not altogether without suspicion of the sequence of the biological events. If I visit a poultry breeder who has a fine stock of thoroughbred game fowls breeding true, and 10 years later – that is to say, 10 fowl-generations later – I go again and find scarcely a recognizable game fowl on the place, I know exactly what has happened. One or two birds of some other or of no breed must have strayed in and their progeny been left undestroyed. Now, in Athens, we have many indications that up to the beginning of the fifth century so long as the phratries and gentes were maintained in their integrity there was rather close endogamy, a condition giving the best chance of producing a homogeneous population. There was no lack of material from which intelligence and artistic power might be derived. Sporadically these qualities existed throughout the ancient Greek world from the dawn of history, and, for example, the vase painters, the makers of the Tanagra figurines, and the gem cutters were presumably pursuing family crafts, much as are the actor families [7] of England or the professional families of Germany at the present day. How the intellectual strains should have acquired predominance we can not tell, but in an in-breeding community homogeneity at least is not surprising. At the end of the sixth century came the “reforms” of Cleisthenes (507 B.C.), which sanctioned foreign marriages and admitted to citizenship a number not only of resident aliens but also of manumitted slaves. As Aristotle says, Cleisthenes legislated with the deliberate purpose of breaking up the phratries and gentes, in order that the various sections of the population might be mixed up as much as possible, and the old tribal associations abolished. The “reform” was probably a recognition and extension of a process already begun; but is it too much to suppose that we have here the effective beginning of a series of genetic changes which in a few generations so greatly altered the character of the people? Under Pericles the old law was restored (451 B.C.), but losses in the great wars led to further laxity in practice, and though at the end of the fifth century the strict rule was reenacted that a citizen must be of citizen birth on both sides, the population by that time may well have become largely mongrelized.

-- Heredity, by Prof. William Bateson, M.A., F.R.S.

William Bateson

Born 8 August 1861

Whitby, Yorkshire[1]

Died 8 February 1926 (aged 64)

Merton

Nationality British

Alma mater St. John's College, Cambridge

Known for heredity and biological inheritance

Awards Royal Medal (1920)

Scientific career

Fields genetics

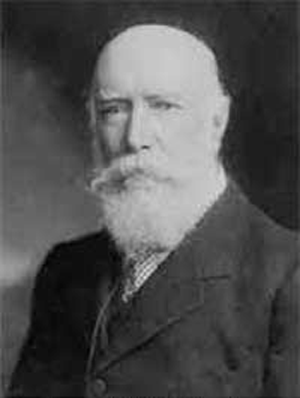

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscovery in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns. His 1894 book Materials for the Study of Variation was one of the earliest formulations of the new approach to genetics.

Biography

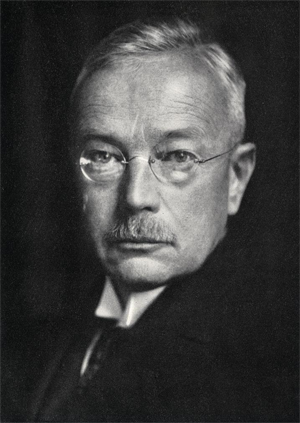

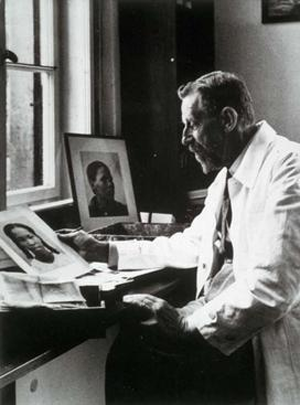

Crayon drawing by the biologist Dennis G. Lillie, 1909

Bateson was born in Whitby on the Yorkshire coast, the son of William Henry Bateson, Master of St John's College, Cambridge. He was educated at Rugby School and at St John's College in Cambridge, where he graduated BA in 1883 with a first in natural sciences.[2]

Taking up embryology, he went to the United States to investigate the development of Balanoglossus.

Balanoglossus is an ocean-dwelling acorn worm (Enteropneusta) genus of great zoological interest because, being a Hemichordate, it is an "evolutionary link" between invertebrates and vertebrates. Balanoglossus is a deuterostome, and resembles the Ascidians or sea squirts, in that it possesses branchial openings, or "gill slits". It has notochord in the upper part of the body and has no nerve chord. It does have a stomochord, however, which is gut chord within the collar. Their heads may be as small as 2.5 mm (1/10 in) or as large as 5 mm (1/5 in).

-- Balanoglossus, by Wikipedia

This worm-like enteropneust hemichordate led to his interest in vertebrate origins. In 1883-4 he worked in the laboratory of William Keith Brooks, at the Chesapeake Zoölogical Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia.[3] Turning from morphology to study evolution and its methods, he returned to England and became a Fellow of St John's. Studying variation and heredity, he travelled in western Central Asia.

Work on biological variation (to 1900)

Bateson's work published before 1900 systematically studied the structural variation displayed by living organisms and the light this might shed on the mechanism of biological evolution,[4] and was strongly influenced by both Charles Darwin's approach to the collection of comprehensive examples, and Francis Galton's quantitative ("biometric") methods.

• THE OBSERVED ORDER OF EVENTS: Steady improvement in the birthright of successive generations; our ignorance of the origin and purport of all existence; of the outcome of life on this earth; of the conditions of consciousness; slow progress of evolution and its system of ruthless routine; man is the heir of long bygone ages; has great power in expediting the course of evolution; he might render its progress less slow and painful; does not yet understand that it may be his part to do so.

• SELECTION AND RACE: Difference between the best specimens of a poor race and the mediocre ones of a high race; typical centres to which races tend to revert; delicacy of highly-bred animals; their diminished fertility; the misery of rigorous selection; it is preferable to replace poor races by better ones; strains of emigrant blood; of exiles.

• INFLUENCE OF MAN UPON RACE: Conquest, migrations, etc.; sentiment against extinguishing races; is partly unreasonable; the so-called "aborigines"; on the variety and number of different races inhabiting the same country; as in Spain; history of the Moors; Gypsies; the races in Damara Land; their recent changes; races in Siberia; Africa; America; West Indies; Australia and New Zealand; wide diffusion of Arabs and Chinese; power of man to shape future humanity.

• POPULATION: Over-population; Malthus--the danger of applying his prudential check; his originality; his phrase of misery check is in many cases too severe; decaying races and the cause of decay.

• EARLY AND LATE MARRIAGES: Estimate of their relative effects on a population in a few generations; example.

• MARKS FOR FAMILY MERIT: On the demand for definite proposals how to improve race; the demand is not quite fair, and the reasons why; nevertheless attempt is made to suggest the outline of one; on the signs of superior race; importance of giving weight to them when making selections from candidates who are personally equal; on families that have thriven; that are healthy and long-lived; present rarity of our knowledge concerning family antecedents; Mr. F.M. Hollond on the superior morality of members of large families; Sir William Gull on their superior vigour; claim for importance of further inquiries into the family antecedents of those who succeed in after life; probable large effect of any system by which marks might be conferred on the ground of family merit.

-- Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, by Francis Galton

In his first significant contribution,[5] he shows that some biological characteristics (such as the length of forceps in earwigs) are not distributed continuously, with a normal distribution, but discontinuously (or "dimorphically"). He saw the persistence of two forms in one population as a challenge to the then current conceptions of the mechanism of heredity, and says "The question may be asked, does the dimorphism of which cases have now been given represent the beginning of a division into two species?”

In his 1894 book, Materials for the study of variation,[6] Bateson took this survey of biological variation significantly further. He was concerned to show that biological variation exists both continuously, for some characters, and discontinuously for others, and coined the terms "meristic" and "substantive" for the two types. In common with Darwin, he felt that quantitative characters could not easily be "perfected" by the selective force of evolution, because of the perceived problem of the "swamping effect of intercrossing", but proposed that discontinuously varying characters could.

In Materials Bateson noted and named homeotic mutations, in which an expected body-part has been replaced by another. The animal mutations he studied included bees with legs instead of antennae; crayfish with extra oviducts; and in humans, polydactyly, extra ribs, and males with extra nipples. These mutations are in the homeobox genes which control the pattern of body formation during early embryonic development of animals. The 1995 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded for work on these genes. They are thought to be especially important to the basic development of all animals. These genes have a crucial function in many, and perhaps all, animals.[7]

In Materials unaware of Gregor Mendel's results, Bateson wrote concerning the mechanism of biological heredity, "The only way in which we may hope to get at the truth is by the organization of systematic experiments in breeding, a class of research that calls perhaps for more patience and more resources than any other form of biological enquiry. Sooner or later such an investigation will be undertaken and then we shall begin to know." Mendel had cultivated and tested some 28,000 plants, performing exactly the experiment Bateson wanted.[8][9][10]

In 1897 he reported some significant conceptual and methodological advances in his study of variation.[11] "I have argued that variations of a discontinuous nature may play a prepondering part in the constitution of a new species." He attempts to silence his critics (the "biometricians") who misconstrue his definition of discontinuity of variation by clarification of his terms: "a variation is discontinuous if, when all the individuals of a population are breeding freely together, there is not simple regression to one mean form, but a sensible preponderance of the variety over the intermediates… The essential feature of a discontinuous variation is therefore that, be the cause what it may, there is not complete blending between variety and type. The variety persists and is not “swamped by intercrossing”. But critically, he begins to report a series of breeding experiments, conducted by Edith Saunders, using the alpine brassica Biscutella laevigata in the Cambridge botanic gardens. In the wild, hairy and smooth forms of otherwise identical plants are seen together. They intercrossed the forms experimentally, “When therefore the well-grown mongrel plants are examined, they present just the same appearance of discontinuity which the wild plants at the Tosa Falls do. This discontinuity is, therefore, the outward sign of the fact that in heredity the two characters of smoothness and hairiness do not completely blend, and the offspring do not regress to one mean form, but to two distinct forms.”

At about this time, Hugo de Vries and Carl Erich Correns began similar plant-breeding experiments. But, unlike Bateson, they were familiar with the extensive plant breeding experiments of Gregor Mendel in the 1860s, and they did not cite Bateson's work. Critically, Bateson gave a lecture to the Royal Horticultural Society in July 1899,[12] which was attended by Hugo de Vries, in which he described his investigations into discontinuous variation, his experimental crosses, and the significance of such studies for the understanding of heredity. He urged his colleagues to conduct large-scale, well-designed and statistically analysed experiments of the sort that, although he did not know it, Mendel had already conducted, and which would be "rediscovered" by de Vries and Correns just six months later.[10]

Founding the discipline of genetics

Further information: Mutationism

Bateson became famous as the outspoken Mendelian antagonist of Walter Raphael Weldon, his former teacher, and of Karl Pearson who led the biometric school of thinking.

Biometrics is the technical term for body measurements and calculations. It refers to metrics related to human characteristics. Biometrics authentication (or realistic authentication)[note 1] is used in computer science as a form of identification and access control.[1][2] It is also used to identify individuals in groups that are under surveillance.[3]

Biometric identifiers are the distinctive, measurable characteristics used to label and describe individuals.[4] Biometric identifiers are often categorized as physiological versus behavioral characteristics.[5] Physiological characteristics are related to the shape of the body. Examples include, but are not limited to fingerprint, palm veins, face recognition, DNA, palm print, hand geometry, iris recognition, retina and odour/scent. Behavioral characteristics are related to the pattern of behavior of a person, including but not limited to typing rhythm, gait, and voice.[6][note 2] Some researchers have coined the term behaviometrics to describe the latter class of biometrics.[7]

More traditional means of access control include token-based identification systems, such as a driver's license or passport, and knowledge-based identification systems, such as a password or personal identification number.[4] Since biometric identifiers are unique to individuals, they are more reliable in verifying identity than token and knowledge-based methods; however, the collection of biometric identifiers raises privacy concerns about the ultimate use of this information.[4][8][9]

-- Biometrics, by Wikipedia

The debate centred on saltationism versus gradualism (Darwin had represented gradualism, but Bateson was a saltationist).[13]

In biology, saltation (from Latin, saltus, "leap") is a sudden and large mutational change from one generation to the next, potentially causing single-step speciation. This was historically offered as an alternative to Darwinism. Some forms of mutationism were effectively saltationist, implying large discontinuous jumps.

Speciation, such as by polyploidy in plants, can sometimes be achieved in a single and in evolutionary terms sudden step. Evidence exists for various forms of saltation in a variety of organisms.

-- Saltation (biology), by Wikipedia

Later, Ronald Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane showed that discrete mutations were compatible with gradual evolution, helping to bring about the modern evolutionary synthesis.

Gradualism, from the Latin gradus ("step"), is a hypothesis, a theory or a tenet assuming that change comes about gradually or that variation is gradual in nature and happens over time as opposed to in large steps.[1] Uniformitarianism, incrementalism, and reformism are similar concepts.

-- Gradualism, by Wikipedia

Between 1900 and 1910 Bateson directed a rather informal "school" of genetics at Cambridge. His group consisted mostly of women associated with Newnham College, Cambridge, and included both his wife Beatrice, and her sister Florence Durham.[14][15] They provided assistance for his research program at a time when Mendelism was not yet recognised as a legitimate field of study. The women, such as Muriel Wheldale (later Onslow), carried out a series of breeding experiments in various plant and animal species between 1902 and 1910. The results both supported and extended Mendel's laws of heredity. Hilda Blanche Killby, who had finished her studies with the Newnham College Mendelians in 1901, aided Bateson in the replication of Mendel's crosses in peas. She conducted independent breeding experiments in rabbits and bantam fowl, as well. [16]

Bateson first suggested using the word "genetics" (from the Greek gennō, γεννώ; "to give birth") to describe the study of inheritance and the science of variation in a personal letter to Adam Sedgwick (1854–1913, zoologist at Cambridge, not the Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873) who had been Darwin's professor), dated 18 April 1905.[17] Bateson first used the term "genetics" publicly at the Third International Conference on Plant Hybridization in London in 1906.[18] Although this was three years before Wilhelm Johannsen used the word "gene" to describe the units of hereditary information, De Vries had introduced the word "pangene" for the same concept already in 1889, and etymologically the word genetics has parallels with Darwin's concept of pangenesis. Bateson and Edith Saunders also coined the word "allelomorph" ("other form"), which was later shortened to allele.[19]

Bateson co-discovered genetic linkage with Reginald Punnett and Edith Saunders, and he and Punnett founded the Journal of Genetics in 1910. Bateson also coined the term "epistasis" to describe the genetic interaction of two independent loci.

Other biographical information

William Bateson became director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution in 1910 and moved with his family to Merton Park in Surrey. He was director there until his sudden death in February 1926. During his time at the John Innes Horticultural Institution he became interested in the chromosome theory of heredity and promoted the study of cytology by the appointment of W. C. F. Newton[20] and in 1923 Cyril Dean Darlington.[21]

In his later years he was a friend and confidant of the German Erwin Baur. Their correspondence includes their discussion of eugenics.

His son was the anthropologist and cyberneticist Gregory Bateson.

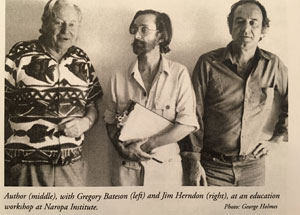

Author [John Riley Perks] (middle), with Gregory Bateson (left) and Jim Herndon (right), at an education workshop at Naropa Institute. Photo: George HolmesFor the unprepared mind, however, LSD can be a nightmare. When the drug is administered in a sterile laboratory under fluorescent lights by white-coated physicians who attach electrodes and nonchalantly warn the subject that he will go crazy for a while, the odds favor a psychotomimetic reaction, or "bummer." This became apparent to poet Allen Ginsberg when he took LSD for the first time at the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, California, in 1959. Ginsberg was already familiar with psychedelic substances, having experimented with peyote on a number of occasions. As yet, however, there was no underground supply of LSD, and it was virtually impossible for layfolk to procure samples of the drug. Thus he was pleased when Gregory Bateson, [Formerly a member of the Research and Analysis Branch of the OSS, Bateson was the husband and co-worker of anthropologist Margaret Mead. An exceptional intellect, he was turned on to acid by Dr. Harold Abramson, one of the CIA's chief LSD specialists] the anthropologist, put him in touch with a team of doctors in Palo Alto. Ginsberg had no way of knowing that one of the researchers associated with the institute, Dr. Charles Savage, had conducted hallucinogenic drug experiments for the US Navy in the early 1950s.

-- Acid Dreams, The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, The Sixties, And Beyond, by Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain

-- The Mahasiddha and His Idiot Servant, by John Riley Perks

In June 1894 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society[22] and won their Darwin Medal in 1904 and their Royal Medal in 1920. He also delivered their Croonian lecture in 1920. He was the president of the British Association in 1913–1914.[23] He founded The Genetics Society in 1919, one of the first learned societies dedicated to Genetics.[24] The John Innes Centre holds a Bateson Lecture in his honour at the annual John Innes Symposium.[25]

He was an atheist.[26][27]

Publications

• Materials for the Study of Variation: Treated with Especial Regard to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species (1894)

• The Methods and Scope of Genetics: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered 23 October 1908 (1908)

• Mendel's Principles of Heredity (1913)

• Problems of Genetics (1913)

• Mendel's Principles of Heredity - A Defence, with a Translation of Mendel's Original Papers on Hybridisation Cambridge University Press

See also

• Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model

• Lucien Cuénot

Notes

1. "William Bateson". Encyclopædia Britannica.

2. "Bateson, William (BT879)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

3. Johns Hopkins University Circular Nov.(1883) vol III. no 27.pg 4.

4. Scientific papers of William Bateson. RC Punnett (Ed) : Cambridge University Press 1928 Vol 1

5. Some cases of variation in secondary sexual characters statistically examined, Proc Zool Soc 1892

6. Materials for the study of variation, treated with especial regard to discontinuity in the origin of species William Bateson 1861–1926. London : Macmillan 1894 xv, 598 p

7. Genetic Science Learning Center. "Homeotic Genes and Body Patterns". Learn Genetics. University of Utah. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

8. Magner, Lois N. (2002). History of the Life Sciences (3, revised ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-2039-1100-6.

9. Gros, Franc̜ois (1992). The Gene Civilization (English Language ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-07-024963-9.

10. Jump up to:a b Moore, Randy (2001). "The "Rediscovery" of Mendel's Work" (PDF). Bioscene. 27 (2): 13–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016.

11. Progress in the study of variation I. Science Progress I, 1897

12. Bateson, W. (1900) "Hybridisation and Cross-Breeding as a Method of Scientific Investigation" J. RHS (1900) 24: 59 – 66, a report of a lecture given at the RHS Hybrid Conference in 1899. Full text:

13. Gillham, Nicholas W. (2001). Evolution by Jumps: Francis Galton and William Bateson and the Mechanism of Evolutionary Change. Genetics 159: 1383–1392.

14. Richmond, Marsha L. (2006). "The 'Domestication' of Heredity: The Familial Organization of Geneticists at Cambridge University, 1895–1910". Journal of the History of Biology. Springer. 39 (3): 565–605. doi:10.1007/s10739-004-5431-7. JSTOR 4332033.

15. "Bateson Family Papers". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 4 October2013.

16. Richmond, M. L. (March 2001). "Women in the early history of genetics. William Bateson and the Newnham College Mendelians, 1900–1910". Isis. 92 (1): 69. doi:10.1086/385040. PMID 11441497.

17. "Naming 'genetics' | Lines of thought". exhibitions.lib.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

18. Gordon M. Shepherd (2010). "Mendel's proposal that heredity is the outcome of 'independent factors' led William Bateson in England in 1906 to suggest the term 'genetics' as a specific biological term for the study of the rules of heredity. Following Bateson, Wilhelm Johannsen in Denmark in 1909 proposed the term 'gene' for the 'independent factors', as well as 'genotype' for the combination of genes in an individual and 'phenotype'" (Creating modern neuroscience Archived 22 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 17).

19. Craft, Jude (2013). "Genes and genetics: the language of scientific discovery". Genes and genetics. Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

20. A. D. H. (January 1928). "Obituary. Mr. W. C. F. Newton". Nature. 121 (3036): 27–28. doi:10.1038/121027b0.

21. "A Brief History of the John Innes Centre". jic.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

22. "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 11 December2010.[permanent dead link]

23. "Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science". Retrieved 21 October 2015.

24. "Genetics Society Website > About > About the Society". genetics.org.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

25. "The Bateson Lecture". John Innes Centre. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

26. "William Bateson was a very militant atheist and a very bitter man, I fancy. Knowing that I was interested in biology, they invited me when I was still a school girl to go down and see the experimental garden. I remarked to him what I thought then, and still think, that doing research must be the most wonderful thing in the world and he snapped at me that it wasn't wonderful at all, it was tedious, disheartening, annoying and anyhow you didn't need an experimental garden to do research." Interview with Dr. Cecilia Gaposchkin by Owen Gingerich, 5 March 1968.

27. Charlton, Noel G. (25 March 2010). Understanding Gregory Bateson: Mind, Beauty, and the Sacred Earth. ISBN 9780791478271.

References

• Schwartz JH (February 2007). "Recognizing William Bateson's contributions". Science. 315 (5815): 1077. doi:10.1126/science.315.5815.1077b. PMID 17322045.

• Harper PS (October 2005). "William Bateson, human genetics and medicine". Human Genetics. 118 (1): 141–51. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-0010-3. PMID 16133188.

• Hall BK (January 2005). "Betrayed by Balanoglossus: William Bateson's rejection of evolutionary embryology as the basis for understanding evolution". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 304 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21030. PMID 15668943.

• Bateson P (August 2002). "William Bateson: a biologist ahead of his time" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 81 (2): 49–58. doi:10.1007/BF02715900. PMID 12532036.

• Gillham NW (December 2001). "Evolution by jumps: Francis Galton and William Bateson and the mechanism of evolutionary change". Genetics. 159 (4): 1383–92. PMC 1461897. PMID 11779782.

• Richmond ML (March 2001). "Women in the early history of genetics. William Bateson and the Newnham College Mendelians, 1900–1910". Isis. 92 (1): 55–90. doi:10.1086/385040. PMID 11441497.

• Harvey RD (January 1995). "Pioneers of genetics: a comparison of the attitudes of William Bateson and Erwin Baur to eugenics". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 49 (1): 105–17. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1995.0007. PMID 11615278.

• Olby R (October 1987). "William Bateson's introduction of Mendelism to England: a reassessment". British Journal for the History of Science. 20 (67): 399–420. doi:10.1017/S0007087400024201. PMID 11612343.

• Harvey RD (November 1985). "The William Bateson letters at the John Innes Institute". The Mendel Newsletter (25): 1–11. PMID 11620779.

• Cock AG (January 1983). "William Bateson's rejection and eventual acceptance of chromosome theory". Annals of Science. 40: 19–59. doi:10.1080/00033798300200111. PMID 11615930.

• Cock AG (1980). "William Bateson's pilgrimages to Brno. Cesty Williama Batesona do Brna". Folia Mendeliana. 65 (15): 243–50. PMID 11615869.

• Cock AG (June 1977). "The William Bateson papers". The Mendel Newsletter. 14: 1–4. PMID 11609980.

• Darden L (1977). "William Bateson and the promise of Mendelism". Journal of the History of Biology. 10 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1007/BF00126096. PMID 11615639.

• Cock AG (1973). "William Bateson, Mendelism and biometry". Journal of the History of Biology. 6: 1–36. doi:10.1007/BF00137297. PMID 11609732.

External links

• Resources in your library

• Resources in other libraries

By William Bateson

• Online books

• Resources in your library

• Resources in other libraries

• Works by William Bateson at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about William Bateson at Internet Archive

• Works by William Bateson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• William Bateson 1894. Materials for the Study of Variation, treated with special regard to discontinuity in the Origin of Species

• William Bateson 1902. Mendel's Principles of Heredity, a defence[permanent dead link]

• Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Bateson, William" . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

• Punnett and Bateson

• Opposition to Bateson – Documents by, or about, Bateson are on Donald Forsdyke's webpages

• Bateson-Punnett Notebooks digitised in Cambridge Digital Library