Part 2 of 2

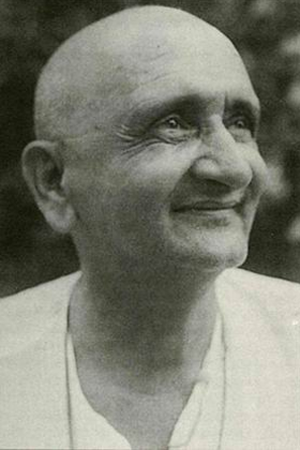

MissionGolwalkar describes the mission of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh as the revitalisation of the Indian value system based on universalism and peace and prosperity to all.[141] Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, the worldview that the whole world is one family, propounded by the ancient thinkers of India, is considered as one of the ideologies of the organisation.[142]

But the immediate focus, the leaders believe, is on the Hindu renaissance, which would build an egalitarian society and a strong India that could propound this philosophy. Hence, the focus is on social reform, economic upliftment of the downtrodden, and the protection of the cultural diversity of the natives in India.[142] The organisation says it aspires to unite all Hindus and build a strong India that can contribute to the welfare of the world. In the words of RSS ideologue and the second head of the RSS, Golwalkar, "in order to be able to contribute our unique knowledge to mankind, in order to be able to live and strive for the unity and welfare of the world, we stand before the world as a self-confident, resurgent and mighty nation".[141]

In Vichardhara (ideology), Golwalkar affirms the RSS mission of integration as:[141]

RSS has been making determined efforts to inculcate in our people the burning devotion for Bharat and its national ethos; kindle in them the spirit of dedication and sterling qualities and character; rouse social consciousness, mutual good-will, love and cooperation among them all; to make them realise that casts, creeds, and languages are secondary and that service to the nation is the supreme end and to mold their behaviour accordingly; instill in them a sense of true humility and discipline and train their bodies to be strong and robust so as to shoulder any social responsibility; and thus to create all-round Anushasana (Discipline) in all walks of life and build together all our people into a unified harmonious national whole, extending from Himalayas to Kanyakumari. — M. S. Golwalkar

Golwalkar and Balasaheb Deoras, the second and third supreme leaders of the RSS, spoke against the caste system, though they did not support its abolition.[143]

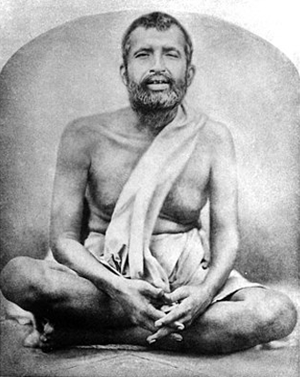

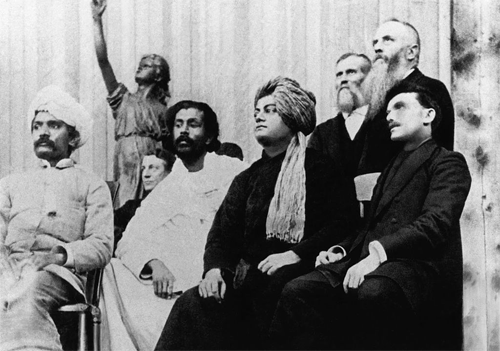

Golwalkar also explains that RSS does not intend to compete in electioneering politics or share power. The movement considers Hindus as inclusive of Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, tribals, untouchables, Veerashaivism, Arya Samaj, Ramakrishna Mission, and other groups as a community, a view similar to the inclusive referencing of the term Hindu in the Indian Constitution Article 25 (2)(b).[144][145][146]

When it came to non-Hindu religions, the view of Golwalkar (who once supported Hitler's creation of a supreme race by suppression of minorities)[147] on minorities was that of extreme intolerance. In a 1998 magazine article, some RSS and BJP members were been said to have distanced themselves from Golwalkar's views, though not entirely.[148]

The non-Hindu people of Hindustan must either adopt Hindu culture and languages, must learn and respect and hold in reverence the Hindu religion, must entertain no idea but of those of glorification of the Hindu race and culture ... in a word they must cease to be foreigners; or may stay in the country, wholly subordinated to the Hindu nation, claiming nothing, deserving no privileges, far less any preferential treatment—not even citizens' rights. — M. S. Golwalkar[149]

Affiliated organisationsFurther information: Sangh Parivar

Organisations that are inspired by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's ideology refer to themselves as members of the Sangh Parivar.[120] In most cases, pracharaks (full-time volunteers of the RSS) were deputed to start up and manage these organisations in their initial years.

The affiliated organisations include:[150]

• Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), literally, Indian People's Party (23m)[151]

• Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, literally, Indian Farmers' Association (8m)[151]

• Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, literally, Indian Labour Association (10 million as of 2009)[151]

• Seva Bharti, Organisation for service of the needy.

• Rashtra Sevika Samiti, literally, National Volunteer Association for Women (1.8m)[151]

• Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, literally, All India Students' Forum (2.8m)[151]

• Shiksha Bharati (2.1m)[151]

• Vishwa Hindu Parishad, World Hindu Council (2.8m)[151]

• Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, literally, Hindu Volunteer Association – overseas wing

• Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, Nativist Awakening Front[152]

• Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Nursery

• Vidya Bharati, Educational Institutes

• Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram (Ashram for the Tribal Welfare), Organisations for the improvement of tribals; and Friends of Tribals Society

• Muslim Rashtriya Manch (Muslim National Forum), Organisation for the improvement of Muslims

• Bajrang Dal, Army of Hanuman (2m)

• Anusuchit Jati-Jamati Arakshan Bachao Parishad, Organisation for the improvement of Dalits

• Laghu Udyog Bharati, an extensive network of small industries.[153][154]

• Bharatiya Vichara Kendra, Think Tank

• Vishwa Samvad Kendra, Communication Wing, spread all over India for media related work, having a team of IT professionals (samvada.org)

• Rashtriya Sikh Sangat, National Sikh Association, a sociocultural organisation with the aim to spread the knowledge of Gurbani to the Indian society.[155]

• Vivekananda Kendra, promotion of Swami Vivekananda's ideas with Vivekananda International Foundation in New Delhi as a public policy think tank with six centres of study

Although RSS has never directly contested elections, it supports parties that are similar ideologically. Although RSS generally endorses the BJP, it has at times refused to do so due to the difference of opinion with the party.

Social service and reform

Participation in land reformsThe RSS volunteers participated in the Bhoodan movement organised by Gandhian leader Vinobha Bhave, who had met RSS leader Golwalkar in Meerut in November 1951. Golwalkar had been inspired by the movement that encouraged land reform through voluntary means. He pledged the support of the RSS for this movement.[156] Consequently, many RSS volunteers, led by Nanaji Deshmukh, participated in the movement.[2] But Golwalkar was also critical of the Bhoodan movement on other occasions for being reactionary and for working "merely with a view to counteracting Communism". He believed that the movement should inculcate a faith in the masses that would make them rise above the base appeal of Communism.[141]

Reform in 'caste'The RSS has advocated the training of Dalits and other backward classes as temple high priests (a position traditionally reserved for Caste Brahmins and denied to lower castes). They argue that the social divisiveness of the caste system is responsible for the lack of adherence to Hindu values and traditions, and that reaching out to the lower castes in this manner will be a remedy to the problem.[157] The RSS has also condemned upper-caste Hindus for preventing Dalits from worshipping at temples, saying that "even God will desert the temple in which Dalits cannot enter".[158]

Jaffrelot says that "there is insufficient data available to carry out a statistical analysis of social origins of the early RSS leaders" but goes on to conclude that, based on some known profiles, most of the RSS founders and its leading organisers, with a few exceptions, were Maharashtrian Brahmins from the middle or lower class[159] and argues that the pervasiveness of the Brahminical ethic in the organisation was probably the main reason why it failed to attract support from the low castes. He argues that the "RSS resorted to instrumentalist techniques of ethnoreligious mobilisation—in which its Brahminism was diluted—to overcome this handicap".[160] However, Anderson and Damle (1987) find that members of all castes have been welcomed into the organisation and are treated as equals.[2]

During a visit in 1934 to an RSS camp at Wardha accompanied by Mahadev Desai and Mirabehn, Mahatma Gandhi said, "When I visited the RSS Camp, I was very much surprised by your discipline and absence of untouchablity." He personally inquired about this to Swayamsevaks and found that volunteers were living and eating together in the camp without bothering to know each other's castes.[161]

Relief and rehabilitationThe RSS was instrumental in relief efforts after the 1971 Orissa Cyclone, 1977 Andhra Pradesh Cyclone[162] and in the 1984 Bhopal disaster.[163][164] It assisted in relief efforts during the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, and helped rebuild villages.[162][165] Approximately 35,000 RSS members in uniform were engaged in the relief efforts,[166] and many of their critics acknowledged their role.[167] An RSS-affiliated NGO, Seva Bharati, conducted relief operations in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. Activities included building shelters for the victims and providing food, clothes, and medical necessities.[168] The RSS assisted relief efforts during the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and the subsequent tsunami.[169] Seva Bharati also adopted 57 children (38 Muslims and 19 Hindus) from militancy affected areas of Jammu and Kashmir to provide them education at least up to Higher Secondary level.[170][171] They also took care of victims of the Kargil War of 1999.[172]

In 2006 RSS participated in relief efforts to provide basic necessities such as food, milk, and potable water to the people of Surat, Gujarat, who were affected by floods in the region.[173][non-primary source needed] The RSS volunteers carried out relief and rehabilitation work after the floods affected North Karnataka and some districts of the state of Andhra Pradesh.[174] In 2013, following the Uttarakhand floods, RSS volunteers were involved in flood relief work through its offices set up at affected areas.[175][176]

ReceptionIndia's first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru had been vigilant towards RSS since he had taken charge. When Golwalkar wrote to Nehru asking for the lifting of the ban on RSS after Gandhi's assassination, Nehru replied that the government had proof that RSS activities were 'anti-national' by virtue of being 'communalist'. In his letter to the heads of provincial governments in December 1947, Nehru wrote that "we have a great deal of evidence to show that RSS is an organisation which is in the nature of a private army and which is definitely proceeding on the strictest Nazi lines, even following the techniques of the organisation".[177]

Sardar Vallabhai Patel, the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of India, said in early January 1948 that the RSS activists were "patriots who love their country". He asked the Congressmen to 'win over' the RSS by love, instead of trying to 'crush' them. He also appealed to the RSS to join the Congress instead of opposing it. Jaffrelot says that this attitude of Patel can be partly explained by the assistance the RSS gave the Indian administration in maintaining public order in September 1947, and that his expression of 'qualified sympathy' towards RSS reflected the long-standing inclination of several Hindu traditionalists in Congress. However, after Gandhi's assassination on 30 January 1948, Patel began to view that the activities of RSS were a danger to public security.[178][179] In his reply letter to Golwalkar on 11 September 1948 regarding the lifting of ban on RSS, Patel stated that though RSS did service to the Hindu society by helping and protecting the Hindus when in need during partition violence, they also began attacking Muslims with revenge and went against "innocent men, women and children". He said that the speeches of RSS were "full of communal poison", and as a result of that 'poison', he remarked, India had to lose Gandhi, noting that the RSS men had celebrated Gandhi's death. Patel was also apprehensive of the secrecy in the working manner of RSS, and complained that all of its provincial heads were Maratha Brahmins. He criticised the RSS for having its own army inside India, which he said, cannot be permitted as "it was a potential danger to the State". He also remarked: "The members of RSS claimed to be the defenders of Hinduism. But they must understand that Hinduism would not be saved by rowdyism."[98]

Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India, did not approve of RSS. In 1948, he criticised RSS for carrying out 'loot, arson, rioting and killing of Muslims' in Delhi and other Hindu majority areas. In his letter to home minister Patel on 14 May 1948, he stated that RSS men had planned to dress up as Muslims in Hindu majority areas and attack Muslims in Muslim majority areas to create trouble. He asked Patel to take strict action against RSS for aiming to create enmity among Hindus and Muslims. He called RSS a Maharashtrian Brahmin movement, and viewed it as a secret organisation which used violence and promoted fascism, without any regard to truthful means and constitutional methods. He stated that RSS was "definitely a menace to public peace".[180]

Field Marshal K. M. Cariappa in his speech to RSS volunteers said "RSS is my heart's work. My dear young men, don't be disturbed by uncharitable comments of interested persons. Look ahead! Go ahead! The country is standing in need of your services."[181]

Zakir Hussain, former President of India, told Milad Mehfil in Monghyar on 20 November 1949, "The allegations against RSS of violence and hatred against Muslims are wholly false. Muslims should learn the lesson of mutual love, cooperation and organisation from RSS."[182][183]

Gandhian leader and the leader of Sarvodaya movement, Jayaprakash Narayan, who earlier had been a vocal opponent of RSS, had the following to say about it in 1977:

RSS is a revolutionary organisation. No other organisation in the country comes anywhere near it. It alone has the capacity to transform society, end casteism and wipe the tears from the eyes of the poor.

He further added, "I have great expectations from this revolutionary organisation which has taken up the challenge of creating a new India."[108]

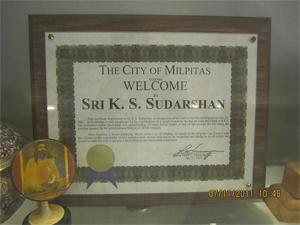

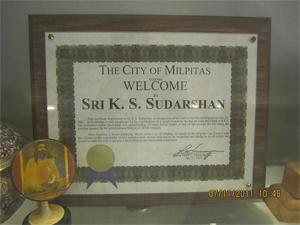

Welcome from City of Milpitas California, USA to K SudarshanCriticisms and accusations

Welcome from City of Milpitas California, USA to K SudarshanCriticisms and accusationsJaffrelot observes that although the RSS with its paramilitary style of functioning and its emphasis on discipline has sometimes been seen by some as "an Indian version of fascism",[184] he argues that "RSS's ideology treats society as an organism with a secular spirit, which is implanted not so much in the race as in a socio-cultural system and which will be regenerated over the course of time by patient work at the grassroots". He writes that "ideology of the RSS did not develop a theory of the state and the race, a crucial element in European nationalisms: Nazism and Fascism"[184] and that the RSS leaders were interested in culture as opposed to racial sameness.[185]

The likening of the Sangh Parivar to fascism by Western critics has also been countered by Jyotirmaya Sharma, who labelled it as an attempt by them to "make sense of the growth of extremist politics and intolerance within their society," and that such "simplistic transference" has done great injustice to our knowledge of Hindu nationalist politics.[186]

RSS has been criticised as an extremist organisation and as a paramilitary group.[3][4][7] It has also been criticised when its members have participated in anti-Muslim violence;[187] it has since formed in 1984, a militant wing called the Bajrang Dal.[21][188] Along with other extremist organisations, the RSS has been involved in riots, often inciting and organising violence against Christians[189] and Muslims.[6]

Involvement with riotsThe RSS has been censured for its involvement in communal riots.

After giving careful and serious consideration to all the materials that are on record, the Commission is of the view that the RSS with its extensive organisation in Jamshedpur and which had close links with the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh had a positive hand in creating a climate which was most propitious for the outbreak of communal disturbances.

In the first instance, the speech of Shri Deoras (delivered just five days before the Ram Navami festival) tended to encourage the Hindu extremists to be unyielding in their demands regarding Road No. 14. Secondly, his speech amounted to communal propaganda. Thirdly, the shakhas and the camps that were held during the divisional conference presented a militant atmosphere to the Hindu public. In the circumstances, the commission cannot but hold the RSS responsible for creating a climate for the disturbances that took place on 11 April 1979.[190][191]

Human Rights Watch, a non-governmental organisation for human rights based in New York, has claimed that the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (World Hindu Council, VHP), the Bajrang Dal, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and the BJP have been party to the Gujarat violence that erupted after the Godhra train burning.[192] Local VHP, BJP, and BD leaders have been named in many police reports filed by eyewitnesses.[193] RSS and VHP claimed that they made appeals to put an end to the violence and that they asked their supporters and volunteer staff to prevent any activity that might disrupt peace.[194][195]

Religious violence in OdishaChristian groups accuse the RSS alongside its close affiliates, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bajrang Dal (BD), and the Hindu Jagaran Sammukhya (HJS), of participation in the 2008 religious violence in Odisha.[196]

Involvement in the Babri Masjid demolition

According to the 2009 report of the Liberhan Commission, the Sangh Parivar organised the destruction of the Babri Mosque.[187][197] The Commission said: "The blame or the credit for the entire temple construction movement at Ayodhya must necessarily be attributed to Sangh Parivar."[198] It also noted that the Sangh Parivar is an "extensive and widespread organic body" that encompasses organisations that address and bring together just about every type of social, professional, and other demographic groupings of individuals. The RSS has denied responsibility and questioned the objectivity of the report. Former RSS chief K. S. Sudarshan alleged that the mosque had been demolished by government men as opposed to the Karsevak volunteers.[199] On the other hand, a government of India white paper dismissed the idea that the demolition was pre-organised.[200] The RSS was banned after the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition, when the government of the time considered it a threat to the state. The ban was subsequently lifted in 1993 when no evidence of any unlawful activity was found by the tribunal constituted under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.[201]

SwayamsevaksMain article: RSS swayamsevak

Political leaders• Deendayal Upadhyaya

• Atal Bihari Vajpayee

• L. K. Advani

• Murli Manohar Joshi

• Narendra Modi

• Rajnath Singh

• Ram Nath Kovind

• Venkaiah Naidu

• Nitin Gadkari

• Manohar Parrikar

• Amit Shah

• Vijay Rupani

• Devendra Fadnavis

• Ram Madhav

• Shankersinh Vaghela

• Keshubhai Patel

• Pramod Mahajan

• Gopinath Munde

• Biplab Kumar Deb

• Manoharlal Khattar

• Dilip Ghosh

Pracharak• Eknath Ranade

• Dattopant Thengadi – Trade Union leader

• Ashok Singhal – VHP president

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, first swayamsevak to become the Prime Minister of India

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, first swayamsevak to become the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi, second swayamsevak to become the Prime Minister of India

Narendra Modi, second swayamsevak to become the Prime Minister of India Ram Nath Kovind, first swayamsevak to become the President of India

Ram Nath Kovind, first swayamsevak to become the President of India Venkaiah Naidu, first swayamsevak to become the Vice-President of IndiaSee also

Venkaiah Naidu, first swayamsevak to become the Vice-President of IndiaSee also• Sangh Parivar

• Rashtra Sevika Samiti

• Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh

References1. Johnson, Matthew; Garnett, Mark; Walker, David M (2017), Conservatism and Ideology, Taylor & Francis, p. 77, ISBN 978-1-317-52899-9

2. Andersen & Damle 1987, p. 111.

3. Curran, Jean A. (17 May 1950). "The RSS: Militant Hinduism". Far Eastern Survey. 19 (10): 93–98. doi:10.2307/3023941. JSTOR 3023941.

4. Bhatt, Chetan (2013). "Democracy and Hindu nationalism". In John Anderson (ed.). Religion, Democracy and Democratization. Routledge. p. 140.

5. McLeod, John (2002). The history of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-0-313-31459-9. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

6. Horowitz, Donald L. (2001). The Deadly Ethnic Riot. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0520224476.

7. Eric S. Margolis (2000). War at the Top of the World: The Struggle for Afghanistan, Kashmir and Tibet. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-415-93062-8. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

8. Embree, Ainslie T. (2005). "Who speaks for India? The Role of Civil Society". In Rafiq Dossani; Henry S. Rowen (eds.). Prospects for Peace in South Asia. Stanford University Press. pp. 141–184. ISBN 0804750858.

9. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 46. ISBN 9789380607047.

10. Priti Gandhi (15 May 2014). "Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh: How the world's largest NGO has changed the face of Indian democracy". DNA India. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

11. "Hindus to the fore". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

12. "Glorious 87: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh turns 87 on today on Vijayadashami". Samvada. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

13. "Highest growth ever: RSS adds 5,000 new shakhas in last 12 months". The Indian Express. 16 March 2016. Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

14. "Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)". Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2010. (Hindi: "National Volunteer Organisation") also called Rashtriya Seva Sang

15. Lutz, James M.; Lutz, Brenda J. (2008). Global Terrorism. Taylor & Francis. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-415-77246-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

16. Jeff Haynes (2 September 2003). Democracy and Political Change in the Third World. Routledge. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-1-134-54184-3. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

17. Chitkara, M. G. (2004). Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge. ISBN 9788176484657.

18. "Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh: How the world’s largest NGO has changed the face of Indian democracy" Archived 5 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine By Priti Gandhi, Updated: 15 May 2014, 08:03 PM IST

19. "BJP becomes largest political party in the world" Archived 12 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Updated: 30 March 2015, 4:20 IST

20. Andersen & Damle 1987, p. 2.

21. Atkins, Stephen E. (2004). Encyclopedia of modern worldwide extremists and extremist groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 264–265. ISBN 978-0-313-32485-7. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

22. Dina Nath Mishra (1980). RSS: Myth and Reality. Vikas Publishing House. p. 24. ISBN 978-0706910209.

23. Krant M. L. Verma Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas (Part-3) p. 766

24. "RSS releases 'proof' of its innocence". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 18 August 2004. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

25. Gerald James Larson (1995). India's Agony Over Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-7914-2412-X.

26. Goodrick-Clarke 1998, p. 59.

27. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 33–39.

28. Kelkar 2011, pp. 2–3.

29. Bhishikar 1979.

30. Kelkar 1950, p. 138.

31. Krant M. L. Verma Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas (Vol 3) p. 854 (Dr. Hedgewar with five other swayamsevaks who established RSS in 1925)

32. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 40–41.

33. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 65–67.

34. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 249.

35. Andersen, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: Early Concerns 1972.

36. Stern, Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia (2001), p. 27. Quote: '... mobilizaiton of Indian Muslims in the name of Islam and in defense of the Ottoman khalifa was inherently "communal", no less than the Islamic movements of opposition to British imperialism which preceded it.... All defined a Hindu no less than a British "other".'

37. Stern, Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia (2001); Misra, Identity and Religion: Foundations of Anti-Islamism in India (2004)

38. Jaffrelot 1996, pp. 19–20.

39. Jaffrelot 1996, p. 34.

40. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 40.

41. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 250.

42. Basu & Sarkar, Khaki Shorts and Saffron Flags 1993, pp. 19–20.

43. Frykenberg 1996, p. 241.

44. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, Chapter 1.

45. Bapu 2013, pp. 97–100.

46. Goyal 1979, pp. 59–76.

47. "RSS aims for a Hindu nation". BBC News. 10 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

48. Nussbaum, The Clash Within 2008, p. 156.

49. Bhatt, Hindu Nationalism 2001, p. 115.

50. Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 188.

51. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, pp. 251–254.

52. Tapan Basu, Khaki Shorts 1993, p. 21.

53. Vedi R. Hadiz (27 September 2006). Empire and Neoliberalism in Asia. Routledge. pp. 252–. ISBN 978-1-134-16727-2. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

54. Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 141.

55. Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 129.

56. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 74.

57. M.S. Golwalkar (1974). Shri Guruji Samgra Darshan, Volume 4. Bharatiya Vichar Sadhana.

58. Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 191.

59. Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 135.

60. Tapan Basu, Khaki Shorts 1993, p. 29.

61. David Ludden (1 April 1996). Contesting the Nation: Religion, Community, and the Politics of Democracy in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 274–. ISBN 0-8122-1585-0. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February2016.

62. Andersen & Damle 1987.

63. Noorani, RSS and the BJP 2000, p. 46.

64. Bipan Chandra, Communalism 2008, p. 140.

65. Sekhara Bandyopadhya?a (1 January 2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 422–. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

66. Bipan Chandra, Communalism 2008, p. 141.

67. Noorani, RSS and the BJP 2000, p. 60.

68. Sumit Sarkar (2005). Beyond Nationalist Frames: Relocating Postmodernism, Hindutva, History. Permanent Black. pp. 258–. ISBN 978-81-7824-086-2. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

69. Partha Sarathi Gupta (1997). Towards Freedom 1943–44,Part III. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 3058–9. ISBN 978-0195638684.

70. Shamsul Islam (2006). Religious Dimensions of Indian Nationalism: A Study of RSS. Media House. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-81-7495-236-3. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

71. "Hindu Nationalist's Historical Links to Nazism and Fascism". International Business Times. 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

72. Gregory, Derek; Pred, Allan Richard (2007). Violent geographies: fear, terror, and political violence. CRC Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9780415951470. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

73. "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 23 April 2006. Archived from the original on 23 April 2006.

74. Golwalkar's We or our nationhood defined: a critique, page 30, Pharos Media & Pub., 2006, written by Shamsul Islam

75. "India". Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

76. Bose, Sumantra (16 September 2013). Transforming India. Harvard University Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 9780674728196.

77. Hansen, Thomas Blom (23 March 1999). The Saffron Wave: Democracy and Hindu Nationalism in Modern India. Princeton University Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 1400823056.

78. Weiner, Myron (8 December 2015). Party Politics in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 183–. ISBN 9781400878413.

79. Dilip Hiro (24 February 2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. Nation Books. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-56858-503-1. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

80. Ian Talbot (16 December 2013). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. pp. 155–. ISBN 978-1-136-79029-4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

81. Kumar, Krishna (22 July 2015). "Double Standards? RSS chiefs used to relish chicken, mutton dishes". The Economic Times.

82. Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 56.

83. Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 57.

84. RSS Primer: Based on Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh Documents. Pharos Media & Publishing. 2010. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-81-7221-039-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

85. Golwalkar, M.S. (1966). Bunch of Thoughts. Bangalore: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana. pp. 237–238. ISBN 81-86595-19-8.

86. RSS Primer: Based on Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh Documents. Pharos Media & Publishing. 2010. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-81-7221-039-7.

87. Shamsul Islam, Religious Dimensions 2006, p. 186.

88. Puniyani, Religion, Power and Violence 2005, p. 142.

89. "Tri-colour hoisted at RSS center after 52 yrs". The Times of India. Nagpur. 26 January 2002. Retrieved 26 January2002.

90. "Activists, who forcibly hoisted flag at RSS premises, freed". Business Standard. Nagpur. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

91. "Trio, who forcibly hoisted tri-colour at RSS premises, set free by court". Nagpur Today. Nagpur. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.[dead link]

92. "rediff.com Special: Naveen Jindal battles for his right to fly the Tricolour".

http://www.rediff.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

93. "Hoisting tricolour a fundamental right: SC – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

94. "Mohan Bhagwat defies restraint, hoists flag in Kerala school: Why RSS did not fly Tricolour for 52 years – Firstpost".

http://www.firstpost.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

95. Hadiz, Vedi. Empire and Neoliberalism in Asia. Routledge. p. 252.

96. Undoing India the RSS Way. Media House. 2002. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-81-7495-142-7.

97. Jeevan Lal Kapur (1970). Report of Commission of Inquiry into Conspiracy to murder Mahatma Gandhi, By India (Republic). Commission of Inquiry into Conspiracy to murder Mahatma Gandhi. Ministry of Home affairs.

98. Patel, Prasad and Rajaji: Myth of the Indian Right 2015, pp. 82.

99. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 88, 89.

100. Graham; Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics 2007, p. 14.

101. Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed Noorani (2000). The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour. LeftWord Books. ISBN 978-81-87496-13-7.

102. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 89.

103. Purushottam Shripad Lele, Dadra and Nagar Haveli: past and present, published by Usha P. Lele, 1987

104. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 130.

105. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 243.

106. Emma Tarlo, Unsettling Memories: Narratives of India's "emergency", Published by Orient Blackswan, 2003, ISBN 81-7824-066-1, ISBN 978-81-7824-066-4

107. Nussbaum, The Clash Within 2008.

108. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalism Reader 2007, p. 297.

109. Tapan Basu, Khaki Shorts 1993, pp. 51–54.

110. Noorani, RSS and the BJP 2000, p. 31.

111. Ghosh, Partha S. (23 May 2012). The Politics of Personal Law in South Asia: Identity, Nationalism and the Uniform Civil Code. Routledge. pp. 110–112. ISBN 9781136705113.

112. Post Independence India, Encyclopedia of Political Parties, 2002, published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN 81-7488-865-9, ISBN 978-81-7488-865-5

113. page 238, Encyclopedia of Political parties, Volumes 33–50

https://books.google.com/books?id=QCh_yd357iIC&pg=PA238114. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalism Reader 2007, p. 175-179.

115. Graham; Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics 2007, p. 253.

116. Graham; Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics 2007, p. 42.

117. Krishna, Ananth V. (2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 240. ISBN 9788131734650.

118. Jaffrelot, Christophe (3 April 2015). "The Modi-centric BJP 2014 election campaign: new techniques and old tactics". Contemporary South Asia. 23 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1080/09584935.2015.1027662. ISSN 0958-4935.

119. Bobbio, Tommaso (1 May 2012). "Making Gujarat Vibrant: Hindutva, development and the rise of subnationalism in India". Third World Quarterly. 33 (4): 657–672. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.657423. ISSN 0143-6597.

120. Bhatt, Hindu Nationalism 2001, p. 113.

121. "Modi effect: 2,000-odd RSS shakas sprout in 3 months". Times of India. 13 April 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

122. Kaushik, Narendra (5 June 2010). "RSS shakhas fight for survival". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

123. "Shakhas have grown by 13% across the country: RSS".

124. "RSS is on a roll: Number of shakhas up 61% in 5 years". The Times of India.

125. K. R. Malkani, The RSS story, Published by Impex India, 1980

126. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004.

127. "Highest growth ever: RSS adds 5,000 new shakhas in last 12 months". 16 March 2016.

128. "RSS added 8000 new members in Kerala last year: State chief".

129. "Kerala Accounts For Over 5000 RSS Shakhas Per Day, Says Sangh". TimesNow. 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

130. "Sowing saffron, reaping lotus". 22 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

131. "Rise of Hindutva in North East: RSS, BJP score in Assam, Manipur but still untested in Arunachal". Firstpost. 20 April 2017. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

132. "Rising RSS clout in rural Punjab took Gagneja down". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

133. "We will reach each Bihar hamlet in 3 years: RSS – Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

134. "66% of RSS shakhas consists of school, college students: Sanghachalak Ramesh Agrawal". The Indian Express. 4 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

135. "उत्तराखंडमेंबढ़ीआरएसएसकीशाखाएं". jagran. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

136. "RSS in Bengal has grown threefold in five years, says report". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

137. "जम्मूऔरकश्मीरमें 500 शाखाएंचलारहाहै – Navabharat Times". Navbharat Times (in Hindi). 20 July 2015.

138. "Rise of Hindutva in North East: Christians in Nagaland, Mizoram may weaken BJP despite RSS' gains in Tripura, Meghalaya". Firstpost. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

139. arisebharat (10 March 2018). "Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh Annual Report 2018". Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

140. Panigrahi, Saswat (9 March 2019). "How Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh is spreading its footprint across the nation". DNA. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

141. M S Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, Publishers: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana

142. H. V. Seshadri, Hindu renaissance under way, Published in 1984, Jagarana Prakashana, Distributors, Rashtrotthana Sahitya (Bangalore)

143. Partha Banerjee. "RSS – THE SANGH: What is it, and what is it not?". SACW. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

144. Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby, "Fundamentalisms Comprehended, Volume 5 of The Fundamentalism Project", University of Chicago Press, 2004, ISBN 0-226-50888-9, ISBN 978-0-226-50888-7

145. Koenraad Elst, 2002, Who is a Hindu?: Hindu revivalist views of Animism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and other offshoots of Hinduism

146. "Constitution of India: Article 25" Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, quote: "Explanation II: In sub-Clause (b) of clause (2), the reference to Hindus shall be construed as including a reference to persons professing the Sikh, Jaina or Buddhist religion".

147. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 55.

148. "A balancing act" Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Hindu.com (12 March 1993). Retrieved on 18 July 2013.

149. Guha, Ramachandra (2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. p. 19. ISBN 9780330396110.

150. Bhatt, Hindu Nationalism 2001, p. 114.

151. Jelen 2002, p. 253.

152. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 169.

153. "Ministers, not group, to scan scams". Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

154. "Parivar's diversity in unity". Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

155. Chitkara, National Upsurge 2004, p. 168.

156. Suresh Ramabhai, Vinoba and his mission, published by Akhil Bharat Sarv Seva Sangh, 1954

157. "RSS for Dalit head priests in temples", Times of India

158. "RSS rips into ban on Dalits entering temples" Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Times of India, 9 January 2007

159. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 45.

160. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 50.

161. K S Bharati, Encyclopedia of Eminent Thinkers, Volume 7, 1998

162. "Ensuring transparency" Archived 2 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 18 February 2001

163. "Enigma of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh". Mainstream weekly. India. 18 August 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

164. Arvind Lavakare (13 February 2001). "The saffron flutters high, yet again". Rediff-News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

165. "Goa rebuilds quake-hit Gujarat village" Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Times of India, 19 June 2002

166. Saba Naqvi Bhaumik, Outlook, 12 February 2001

167. India-Today, 12 February 2001 issue

168. "Relief missions from Delhi", The Hindu

169. "Tsunami toll in TN, Pondy touches 7,000", Rediff, 29 December 2004

170. Pawan Bali & Aswathy Kumar (28 June 2006). "Jammu kids get home away from guns". IBN live. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

171. "JK: RSS adopts militancy hit Muslim children". News.oneindia.in. 25 June 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

172. "Fund of Controversy" Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Times of India, 14 December 2002

173. "RSS joins relief operation in flood-hit Surat" Archived 19 June 2007 at Archive.today, Organiser.org

174. "RSS volunteers fan out to do relief work". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

175. "RSS help for Uttarakhand flood victims" Archived 29 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 26 June 2013.

176. "RSS swings into action in flood-ravaged Uttarakhand" Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Niti Central, Retrieved on 18 July 2013.

177. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 87, 88.

178. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 86-.

179. Graham; Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics 2007, p. 12.

180. Patel, Prasad and Rajaji: Myth of the Indian Right 2015, pp. 113.

181. Damle, Shridhar D. (1987). The Brotherhood in Saffron. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Revivalism. New Delhi: Vistaar Publications. p. 56. ISBN 0-8133-7358-1.

182. Ralhan, Om Prakash (1998). Post-independence India. ISBN 978-81-7488-865-5. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

183. "Rediff on the NeT: Varsha Bhosle on the controversy surrounding Netaji and the RSS". Rediff.com. 14 September 1947. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

184. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, p. 51.

185. Jaffrelot, Hindu Nationalist Movement 1996, pp. 57–58.

186. Hindu Nationalist Movement Archived 27 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu – 24 September 2005

187. "How the BJP, RSS mobilised kar sevaks". Indianexpress. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

188. Breker, Torkel (2012). Chris Seiple; Dennis R. Hoover; Pauletta Otis (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Security. Routledge. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0415667449.

189. Parashar, Swati (2014). Women and Militant Wars: The Politics of Injury. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-0415827966.

190. From Jitendra Narayan Commission report on Jamshedpur riots of 1979

191. Engineer, Asgharali (1991). Communal Riots in Post-Independence India-Sangam Books 1984, 1991, 1997-Asgar ali engineer. ISBN 978-81-7370-102-3. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

192. Corrêa, Sonia; Rosalind Petchesky; Richard Parker (2008). Sexuality, Health and Human Rights (New ed.). Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-0415351188.

193. "India: Gujarat Officials Took Part in Anti-Muslim Violence". Hrw.org. 30 April 2002. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

194. RSS, VHP appeal for peace in Gujarat

http://www.rediff.com/news/2002/mar/02train10.htm Archived 13 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

195. Dipankan Bandopadhyay (December 2016). "Illusory Nationalism and its woes". Politics Now. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

196. Blakely, Rhys (20 November 2008). "Hindu extremists reward to kill Christians as Britain refuses to bar members". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

197. "Excerpts from the Liberhan Commission report". Hindustan Times. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

198. "Liberhan comes down heavily on Vajpayee, Advani – Rediff.com India News". News.rediff.com. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

199. "Sudarshan contests Liberhan's claim". India Today. PTI. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

200. "Liberhan Takes Suspicions As Proof". The New Indian Express. Bengalooru Edition. 7 December 2009.

201. Noorani, A.G. (2000). The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labor. New Delhi. p. 99. ISBN 9788187496137.

Bibliography

Sources• Bakaya, Akshay (2004), Anne Vaugier-Chatterjee (ed.), "Lessons from Kurukshetra the RSS Education Project", Education and Democracy in India, New Delhi: Manohar, ISBN 8173046042

• Bapu, Prabhu (2013), Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India, 1915-1930: Construction Nation and History, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415671651

• Basu, Tapan; Sarkar, Tanika (1993), Khaki Shorts and Saffron Flags: A Critique of the Hindu Right, Orient Longman, ISBN 0863113834

• Bhatt, Chetan (2001), Hindu Nationalism: Origins, Ideologies and Modern Myths, Berg Publishers, ISBN 1859733484

• Chitkara, M. G. (2004), Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, APH Publishing, ISBN 8176484652

• Curran, Jean Alonzo (1951), Militant Hinduism in Indian Politics: A Study of the R.S.S., International Secretariat, Institute of Pacific Relations, retrieved 27 October 2014

• Frykenberg, Robert Eric (1996), Martin E. Marty; R. Scott Appleby (eds.), "Hindu fundamentalism and the structural stability of India", Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies and Militance, University of Chicago Press, pp. 233–235, ISBN 0226508846

• Graham, Bruce Desmond (3 December 2007), Hindu Nationalism and Indian Politics: The Origins and Development of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-05374-7

• Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (1998), Hitler's Priestess: Savithri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth and the Neo-Nazism, New York University, ISBN 0-8147-3110-4

• Goyal, Des Raj (1979), Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Delhi: Radha Krishna Prakashan, ISBN 0836405668

• Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996), The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 978-1850653011

• Jaffrelot, Christophe (2007), Hindu Nationalism - A Reader, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13097-2

• Kelkar, D. V. (4 February 1950), "The R.S.S." (PDF), Economic Weekly, retrieved 26 October 2014

• Kelkar, Sanjeev (2011), Lost Years of the RSS, SAGE, ISBN 978-81-321-0590-9

• Misra, Amalendu (2004), Identity and Religion: Foundations of Anti-Islamism in India, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-81-321-0323-3

• Sirsikar, V. M. (1988), Eleanor Zelliott; Maxine Bernsten (eds.), "My Years in the RSS", The Experience of Hinduism: Essays on Religion in Maharastra, SUNY Press, pp. 190–203, ISBN 0887066623

• Stern, Robert W. (2001), Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia: Dominant Classes and Political Outcomes in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-97041-3

• Venkatesan, V. (13 October 2001). "A pracharak as Chief Minister". Frontline. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

• Anand, Adeesh (2007), Shree Guruji And His R.S.S., Delhi: M.D. Publication Pvt. Ltd.

• Andersen, Walter (1972), "The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: I: Early Concerns", Economic and Political Weekly, 7 (11): 589–597 (591–2), JSTOR 4361126

• Andersen, Walter K.; Damle, Shridhar D. (1987), The Brotherhood in Saffron: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Revivalism, Delhi: Vistaar Publications

• Basu, Tapan (1993), Khaki Shorts and Saffron Flags: A Critique of the Hindu Right, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-0-86311-383-3

• Bipan Chandra (2008), Communalism in Modern India, Har-Anand, ISBN 978-81-241-1416-2

• Chitkara, M. G. (1997), Hindutva, APH Publishing, ISBN 81-7024-798-5

• Shamsul Islam (2006), Religious Dimensions of Indian Nationalism: A Study of RSS, Media House, ISBN 978-81-7495-236-3

• Noorani, Abdul Gafoor (2000), The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour, LeftWord Books, ISBN 978-81-87496-13-7

• Nussbaum, Martha Craven (2008), The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03059-6

• Puniyani, Ram (2005), Religion, Power and Violence: Expression of Politics in Contemporary Times, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-81-321-0206-9

• Neerja Singh (28 July 2015), Patel, Prasad and Rajaji: Myth of the Indian Right, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-93-5150-266-1

Books• Bhishikar, C. P. (1979), Keshave: Sangh Nirmata, New Delhi: Suruchi Sahitya Prakashan

• Golwalkar M.S. Shri Guruji Samagra Suruchi Prakashan New Delhi 110055 India

• Golwalkar, M. S. (1980), Bunch of thoughts, Bangalore: Jagarana Prakashana

• Sinha Rakesh Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar 2003 New Delhi Publication Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Government of India

• Dr.Mehrotra N.C. & Dr.Tandon Manisha Swatantrata Andolan Mein Shahjahanpur Ka Yogdan 1995 Shahjahanpur India Shaheed-E-Aazam Pt. Ram Prasad Bismil Trust.

• Jelen, Ted Gerard (2002), Religion and Politics in Comparative Perspective: The One, The Few, and The Many, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-65031-3

• Chitkara, M. G. (2004), Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, APH Publishing, ISBN 9788176484657

Publications• "Panchajanya" (in Hindi). RSS weekly publication.

• "Organiser". RSS weekly publication.

• Bunch of Thoughts, Bangalore, India: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashan, 1966, ISBN 81-86595-19-8, archived from the original on 28 January 2007, retrieved 29 October 2006 (A Collection of Speeches by Golwalkar).

• Weekly Swastika (A Nationalist Bengali News Weekly)

• Biographies of Dr. Hedgewar The founder of RSS (in Hindi and English)

External links• Official website