Suzuki Daisetsu and Swedenborg: A Historical Background

by Yoshinaga Shin’ichi 吉永進一

translated by Erik Schicketanz

Modern Buddhism in Japan

edited by Hayashi Makoto, Ōtani Eiichi, and Paul L. Swanson

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Suzuki Daisetsu and Swedenborg

A Historical Background

The present article is the updated English version of an article previously published in 2005 in Japanese. It has been amended substantially in light of the subsequent work done by other scholars. At the time of the article’s original publication, Thomas Tweed had already begun his groundbreaking work on the issue of the influence of esotericism on modern Buddhism with his volume The American Encounter with Buddhism (1992). This volume was followed by the pioneering work of Jorn Borup,1 along with further comprehensive research by Thomas Tweed (published in the same year, 2005, as my own original article),2 and the work of Wakoh Shannon Hickey (2008).3 While the overall number of publications on the topic remains relatively small, it has attracted the attention of American and European scholars and been cited time and again since the 1990s.

My intentions in writing this article were threefold. Having been inspired by Tweed’s American Encounter with Buddhism, my main aim lay in elucidating the relationship between Swedenborgianism and Japanese Buddhism on the basis of Japanese source materials. The second aim of this article was to familiarize the readership with a lecture by Suzuki Daisetsu that was included in the Annual Report of the Swedenborg Society (arss), which was kindly pointed out to me by a librarian (Nancy Dawson) during a visit to the Society’s headquarters in London in 2003. In this lecture, rather than discuss the reception of Swedenborg in Japan, Daisetsu talked frankly about his own admiration for Swedenborg. The significance of the lecture thus lies in showing Daisetsu’s deep commitment to Swedenborgianism. My third aim was to discuss the way in which Swedenborg’s thought had been absorbed into Daisetsu’s own philosophy. Regrettably, the first version of this paper failed to address this last point sufficiently.

Before taking up the main subject, I will briefly outline the historical facts concerning Suzuki’s involvement with two kinds of Western esotericism, namely Theosophy and Swedenborgianism.

It should be pointed out at the outset that there is actually only a little research about the theosophical activities of Suzuki Daisetsu and his wife Beatrice that is grounded in a thorough reading of the primary sources. Among the small body of essential works in existence, an important contribution is the article by Adele Algeo (2005) based on a survey of materials in the possession of the Theosophical Society. According to Algeo, Suzuki Daisetsu and his wife engaged with a Theosophical lodge on two occasions. The first instance was with the International Lodge, founded by the Irish poet James Cousins in Tokyo in March 1920. Beatrice and Daisetsu had not become Theosophists during their time in the United States, but did so when they joined the International Lodge. According to the chronology included in the “Fundamental Materials in Suzuki Daisetsu Research” (Kirita 2005), Daisetsu and his wife took part in seven meetings of the lodge between 13 March and 26 June 1920.4 The secretary of the lodge at the time of its founding was Kon Buhei, but he resigned shortly thereafter. He was succeeded by Jack Brinkely, and Suzuki Daisetsu took on the position of president. However, Suzuki’s involvement with the lodge ended when he left Tokyo in April 1921 to become a lecturer at Ōtani University.

Suzuki’s second involvement with Theosophy came on 8 May 1924. On that day, the first meeting of the newly established Mahayana Lodge was held at the Suzuki’s Kyoto residence. Of the eight founding members, Emma Erskine Hahn, Beatrice Suzuki, Suzuki Daisetsu, as well as Ryukoku University lecturers Jisoji Tetsugai and Utsuki Nishū were already members of the Theosophical Society. The latter two were both priests of the Nishihonganji sect and had joined the Theosophical Society while in Los Angeles on mission duty. According to the chronology provided in Kirita 2005,5 the lodge met at least sixteen times and is believed to have existed until 6 October 1929. Beatrice was an enthusiastic supporter of Krishnamurti’s Order of the Star in the East, which was a kind of messianic movement that existed within the Theosophical Society. Its central figure, Krishnamurti, personally disbanded the organization in August 1929 and it is likely that the activities of the Mahayana Lodge also ended following this event.

Apart from Utsuki and Jisoji, the Mahayana Lodge was joined by other university lecturers as well, among them Uno Enkū, Akamatsu Chijō, Hatani Ryōtai, and Yamabe Shūgaku. According to the volume on Suzuki Daisetsu edited by Hisamatsu Shin’ichi et al. (1971, 470), the activities of the Mahayana Lodge were not dedicated to the study of Theosophical texts; the lodge rather provided a venue for members to present their research of religious studies.6 It appears as if there were only a handful of members, including Beatrice, who were enthusiastic about “esoteric” activities, like those of the Order of the Star of the East.7

While the Theosophical Lodge was established at his own residence, Suzuki Daisetsu did not seem to be enthusiastic about its administration. (Since Beatrice Suzuki acted as secretary and Utsuki Nishū had the position of treasurer, it seems as if these two were in charge of the lodge’s actual affairs.) Also, while Suzuki Daisetsu hardly ever discussed Theosophy in his publications, critical remarks about it can be found in his correspondences. As Tweed writes, ”Suzuki seems more negative about Theosophy by the end of the 1920s.”8

On the other hand, compared to Theosophy, there are many works by Daisetsu dealing with Swedenborgianism. He wrote the following five monographs about Swedenborg.

1. Tenkai to jigoku 天界と地獄 (Heaven and hell). Tokyo: Yūrakusha, 1910.

2. Suedenborugu スエデンボルグ, Tokyo: Heigo Shuppansha, 1913.

3. Shin Erusaremu to sono kyōsetsu 新エルサレムとその教説 (The new Jerusalem and its heavenly doctrine). Tokyo: Heigo Shuppansha, 1914.

4. Shinchi to shin’ai 神知と神愛 (Divine wisdom and divine love). Tokyo: Heigo Shuppansha, 1914.

5. Shinryo ron 神慮論 (Divine providence). Tokyo: Heigo Shuppansha, 1915.

Apart from the biographical Suedenborugu, the remaining four volumes are all translations. The translation and publication costs of these volumes were covered by the Swedenborg Society as part of their activities to disseminate Swedenborg’s texts. Daisetsu himself had also been a member of the Japanese Swedenborg Society (Nihon Suedenborugu Kyōkai) for a short while in the 1910s (the early Taishō period). In addition to the above, there are further fragmentary writings on Swedenborg by Daisetsu, the two most comprehensive of these being:

6. “Suedenborugu” スエデンボルグ, in Sekai seiten gaisan 世界聖典外纂 (Sekai Seiten Zenshū Kankōkai 1923, 323–29.

7. “Suedenborugu (sono tenkai to tarikikan)” スエデンボルグ(その天界と他力観), in Chūgai nippō, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 February 1914. Later included in the collection Zuihitsu zen 随筆 禅 (Suzuki 1926).

Furthermore, a speech given in English by Daisetsu in 1912 at the Swedenborg Society in London is included in the volume listed below and has been consulted in the writing of this article:

8. Annual Report of the Swedenborg Society 1912, Swedenborg Society, 1912.

Just in terms of the number of publications, in 1915 Daisetsu had more works on Swedenborg than monographs on Zen. Daisetsu’s thought was rich in nuance and it is impossible to say anything decisive based on this limited data, but it is impossible to deny that he was sympathetic towards Swedenborg’s philosophy. Daisetsu was not alone, however, in his appreciation of Swedenborg. In keeping with my three aims outlined in the beginning, this article will first discuss the encounter of other Japanese Buddhists with Swedenborg. Next, I will touch on Daisetsu’s appraisal of Swedenborg. Lastly, I will examine the influence Swedenborgianism had on Daisetsu.

Swedenborg in the Mid-1880s to Mid-1890s

The first Japanese to come into touch with Swedenborgianism were figures such as Mori Arinori sent by the Satsuma domain to study abroad at the end of the Edo period. Through the introduction of Laurence Oliphant, they joined the spiritual colony, New Life, which was presided over by Thomas Lake Harris, a Swedenborgian medium. Among the Japanese who had been at New Life, Arai Ōsui was the only one who continued his religious activities after returning to Japan in 1899. While Arai’s thought is recently receiving a gradual and deserved reevaluation, due to his reclusive lifestyle, his Swedenborgian philosophy was at the time only transmitted to a small circle of persons, including Tanaka Shōzō.9

On the other hand, Swedenborg became known among Buddhists during the decade between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s. This was due to the exchange that existed between America’s first Buddhist magazine, Buddhist Ray, and contemporary progressive Buddhist magazines in Japan, such as Hanseikai zasshi 反省会雑誌 and Kaigai Bukkyō jijō 海外仏教事情.

America’s first Buddhist magazine, Buddhist Ray (1888–1894), was published in Santa Cruz, California, by Philangi Dasa. This was the Tibetan name used by Herman Carl Vetterling (1849–1931), an American of Swedish descent. Vetterling was born in Sweden, immigrated to the United States, studied at Urbana University’s Theological School, graduated in 1876, and was ordained a minister in the Swedenborgian New Church the following year. He resigned, however, in 1881, and became critical of the New Church. He studied homeopathy at Hahnemann College in Philadelphia and was active for a while as a doctor. He also joined the Theosophical Society for a time, and between 1884 and the following year he contributed several articles about Swedenborg to the Theosophist, the magazine of the Theosophical Society. However, he disassociated himself from the society in 1887 and subsequently became very critical of it. After publishing Swedenborg the Buddhist: or the Higher Swedenborgianism, Its Secrets, and Thibetan Origin in Los Angeles in 1887, Vetterling moved to Santa Cruz and began to publish the magazine Buddhist Ray.10 In his later years, Vetterling became a spiritual seeker who studied Jacob Bochme and moved in between various forms of spiritual thought, becoming an individualist who mistrusted sects and religious organizations. Vetterling can be described as a self-made Buddhist, one who had created himself through the study of Buddhist texts. His main work, Swedenborg the Buddhist, takes the form of a dream vision in which Swedenborg converses with a Buddhist monk. The Buddhism presented in this work combines information about Buddhism found in English translations of Buddhist texts available at the time along with Theosophy. Swedenborg’s writings are often discussed alongside occult and Orientalist works, and the work can be read as a comparative treatment of Eastern and Western esotericism. Vetterling was not merely motivated by academic interest. He engaged in a comparison of the religious thought of the East and West in order to decipher Swedenborg’s “lost sacred word” (the universal truth common to all mankind that existed in antiquity and held to still in Central Asia). By doing so, he sought to prove that Swedenborgianism and Buddhism are no less than the same.

The year that Vetterling became active as a Buddhist coincided with the inauguration of a progressive Buddhist reform movement in Japan. In 1886, students of the Nishi Honganji-operated school Futsū kyōkō 普通教校 started the Hanseikai 反省会 movement, advocating abstinence from alcohol and the strengthening of moral discipline among Buddhists. Publication of the movement’s magazine Hanseikai zasshi began in August 1887. By coincidence, it was during the same period that Matsuyama Matsutarō, an English teacher at the Futsū kyōkō, began to correspond with several foreign “Buddhists” (most of them Theosophists), such as Vetterling and William Q. Judge, head of the Theosophical Society in America. Matsuyama contributed translations of letters he had received from abroad as well as articles about Theosophy to the inaugural issue of Hanseikai zasshi. In the second issue, which appeared in January 1888 and coincided with the publication of the first issue of Buddhist Ray, the column “News from the Western Correspondence Society” (Ōbei tsūshin kaihō 欧米通信会報) was established. In the course of this year, “News from Europe and America” was expanded and became its own magazine, Kaigai Bukkyō jijō 海外仏教事情 (published from 1888 to 1893). Translations were not only featured in Hanseikai zasshi or Kaigai Bukkyō jijō, but also in the Jōdo sect publication Jōdo kyōhō 浄土教 報, the supra-denominational magazine Bukkyō 仏教, the Tendai magazine Shimei yoka 四明余霞, and the Shingon magazine Dentō 伝燈. Vetterling’s letters and articles from Buddhist Ray were also published first in Kaigai Bukkyō jijō, and since 1890, in Shimei yoka. This was because Ōhara Kakichi, the central figure behind Shimei yoka, had been in close correspondence with Vetterling. In 1893, the Japanese translation of Swedenborg the Buddhist was published under the title Zuiha Bukkyōgaku 瑞派仏教学 (Hakubundō, 1893) with an exclusive foreword by Vetterling for the Japanese edition, as well as a foreword by Nakanishi Ushirō, a famous Buddhist reformer at the time. Ōhara Kakichi was responsible for the translations.11

A number of articles were published in Buddhist magazines from the mid-1880s to the mid-1890s which mention Swedenborg’s name in their titles. The earliest of these was the article “Suedenborii shi no ritsugi,” which appeared in issue 5 of Hanseikai zasshi in April 1888 (Meiji 21). This was a translation of the article “Dicta of Swedenborg” published in the first issue of Buddhist Ray. The article’s content is summed up by the following quote:

That in archaic times there existed throughout the world a system of Spiritual Truth handed down from pre-archaic times. That this system of truth, which may be called Ancient Word, exists still, and is in the hands of Central-Asian Buddhists. (The Buddhist Ray 1 [Jan. 1888]: 1)

Furthermore, in Hanseikai zasshi’s ninth issue from August 1888, the article “Bussha Suedenborii” (The Buddhist Swedenborg) appeared, and the nineteenth issue from June 1889 featured the article “Bussha toshite no Suiidenboogu shi” (Swedenborg as a Buddhist). Both of these were likely based on articles from Buddhist Ray.

Of particular interest is the article on “‘Sueedenboorugu’ no zenron” (Swedenborg on Zen) which was published in the monthly Rinzai magazine Katsuron’s third issue from May 1890. Katsuron 活論 was edited and published by Hirai Kinza, who had been responsible for inviting Colonel Olcott to Japan in 1889. The anonymous author of the introduction to this article (probably penned by either Hirai or the article’s translator, Araki Toshio) states that, “Swedenborg emerged as a famous religious philosopher in the previous century and propagated Buddhism. Now, since Buddhism is prospering, people frequently discuss Swedenborg” (Katsuron 3 [25 May 1890]: 21–22). This shows that Swedenborg was already known as a Buddhist in Japan. The original author of this article is given in Japanese as “Osukeauitchi” (the original spelling is unknown; maybe “Oskarewich”), and based on my discussion below, it is likely that this was another name used by Vetterling.

The article takes the form of a dialog between a Christian belonging to the New Church and a Buddhist. The “Buddhist,” who stands in for the article’s author, argues that the New Church’s interpretation of Swedenborg is wrong and that true Swedenborgianism is identical with Buddhism. According to this argument, Swedenborg entered “contemplative samadhi” under the guidance of a Tibetan Buddhist, and it is claimed that the method he used was to block out his senses.12 It is no coincidence that among the articles dealing with Swedenborg and Buddhism, it was this article concerning religious experience that was already available in translation in 1890. This fact should probably be seen as an expression of the interest that existed in the notion of “experience” among progressive-reformist Japanese Buddhists.13 As will be discussed later, the key-words “Swedenborg” and “Theosophy” were discussed in connection with “experience,” at least by Ishidō Emyō and Taoka Reiun.

Hirai went to America in 1892 in order to propagate Buddhism and received acclaim for a speech he gave at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, wherein he criticized the unequal treaties.14 Apart from this, Hirai gave speeches in various places about the topic of synthetic religion (sōgō shūkyō 総合宗教). For instance, in a speech entitled “Mahayana and Hinayana” given in May 1892 in Los Angeles, Hirai argued that the object of veneration in all religions is “truth” (shinri 真理), and declared that all religions are the same. To illustrate this point, he quoted a Japanese waka that reads, “While at the base of the mountain the paths leading upward are many, is it not the same moon in the sky that all see in the end?” (wakenoboru fumoto no michi wa ōkeredo, onaji takane no tsuki o miru kana; Los Angeles Herald, 9 May 1892).

In 1893, Hirai published the article “Religious Thought in Japan” in English in the magazine Arena (Hirai 1893). To begin with, he stresses that the Japanese are not idol worshippers (that is, savages), but seekers of the truth. The Shinto purification rite, too, is nothing other than a spiritual exercise (gyō 行) to cleanse the mind (kokoro 心) and bring it into harmony with truth. He explains that the term kami, used for the Shinto deities, comes from the word kangami, to think about the truth. In Buddhism, buddha nature (busshō 仏性) includes the truth, the understanding of the truth, and the potentiality to know the truth. Since humans have consciousness and are made out of inanimate matter, inanimate matter also has consciousness. Therefore, all things, including inanimate matter, have buddha nature. Buddhism means the understanding of truth, and if the Christian god is also the essence of universal reason, then there is no difference between the two religions. On the other hand, the object of faith cannot be grasped logically and is unknowable. In other words, all religions share an a priori faith in an unknown entity, and the various truths pertaining to the existence of this entity constitute the edifice of all religions. Therefore, by synthesizing the various religions, it is possible to obtain a more complete truth. In the case of Japan, there were Prince Shōtoku (who not only promoted Buddhism but also Shinto), Kōbō Daishi Kūkai (who blended Buddhism and Shinto), and Ishida Baigan (who founded Shingaku 心学 in the early modern period combining Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism). This kind of synthetic religion, reflecting the full spectrum of Japan’s original wisdom, Hirai also refers to as Japanism. Hirai concludes his article by expressing hope that through the World’s Congress of Religions, which will be held shortly, Syntheticism and Japanism will be put into practice. Hirai thus employed a strategy in America of invoking the global ideal of Syntheticism while at the same time stressing the superiority of Japanism and covertly criticizing Christianity. Putting the issue of Japanism aside, at least in regard to Syntheticism, Hirai shared common ground with liberal religious thinkers such as Jenkin Lloyd Jones.15 After returning to Japan, he discussed his religious faith in the following way in a lecture he gave in 1899: “Whether ‘Mohammed’ or ‘Swedenborg’, Buddhism or Christianity, my belief is that despite these divisions, they [religions] are all fundamentally one” (Hirai 1899: 16). That he lists him alongside other religious founders shows in what high esteem Hirai held Swedenborg.

There are hardly any writings by Hirai himself about Swedenborg, but there exists a discussion of Swedenborg that was influenced by Hirai. This is Ishidō Emyō’s article “Suedenbori to Kōbō Daishi” (Swedenborg and Kōbō Daishi), published in the Shingon sect magazine Dentō from issue 98 (28 July 1895) to issue 103. Ishidō was a priest in the Shingon sect who had studied at the Unitarian Senshin Gakuin, later becoming chief editor at Dentō and finally acting as superintendent priest (kanchō) of the Omuro branch of the Shingon sect.

Ishidō’s understanding of Swedenborg basically followed that of Vetterling. He held that the essence of Swedenborg’s philosophy was Buddhism, and that because it was the product of Asian spirituality, if read by someone not versed in Buddhism, it would be as if someone were to enter a treasure mountain and return empty-handed (Dentō 101 [13 Sept. 1895): 16). From this position, Ishidō compared Buddhism and Swedenborg’s philosophy by dividing the comparison into four categories: theories concerning the cosmos, the identical essence of sentient beings and buddhas, the stages of the soul, and life. I will touch on the first two categories here.

In regard to cosmology, Ishidō points out that Kōbō Daishi (Kūkai) saw matter and mind (busshin 物心) as originally neither arising nor ceasing and thus constant. In this regard, Ishidō saw a congruence with Swedenborg. However, according to Ishidō, while Swedenborg does talk about the existence of an invisible heavenly god, this god does not have human guise. Rather, god stands in for the truth, “hiding the rational ideal,” in Ishidō’s words. Next, he proceeded to explain the correspondence that exists between “part” and “whole” in Swedenborg’s thought. Parts possess the same quality as the whole. A heart, for example, is made of infinitely small hearts. All things in the universe contain the entirety of creation. Where Swedenborg says that “not only are all things your possession, but you are all things,” Kōbō Daishi states that, “every particle and every dharma are the body of the dharma realm” (ichijin ippō mina kore hokkaitai 一塵一法皆是法 界体). Drawing on Swedenborg’s statement that “the human body is strictly universal,” Ishidō held that this was identical to Kōbō Daishi’s “Principle of Attaining Buddhahood in the Present Body” (Sokushin jōbutsu gi 即身成仏 義). Swedenborg had stated that not only men and women, old and young, but also animals and plants possess divine nature, and Ishidō likened this to tathāgatagarbha thought in Buddhism, seeing it as corresponding to Kōbō Daishi’s statement that, “everything that has form and possesses consciousness also has buddha nature” (ugyō ushiki ha kanarazu busshō o gusu 有形有 識必具仏性).

The idea that sentient beings and buddhas are of the same essence (shōbutsu funi 生仏不二) is an extension of this inner divine nature and constitutes a theory of salvation. According to Ishidō, Kōbō Daishi’s idea of the shared essence of sentient beings and buddhas is similar to Swedenborg’s theory of the intimate connection between humans and god. Drawing on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s discourse on compensation, Ishidō further erased the distinction between self and other, and argued that by reaching a stance of treating all with the same benevolence (isshi dōjin 一視同仁) and accepting the knowledge and virtues of others as one’s own, it becomes possible even for ordinary people to reach the realm of saints and buddhas. However, ordinary people and buddhas are not initially the same. Distinctive characteristics obviously exist in the beginning. Achieving this state of sameness requires a struggle employing earnest intention (hosshin 発心) and faith-based effort (shinju 信修). This holds true whether it be Yangming learning (which emphasizes inner spirituality in the form of good knowledge and good capacity), Swedenborg, or Kōbō Daishi.

Having said that, Ishidō writes that one should not search for guidelines to salvation in an external church or system, but rather within one’s own mind. He holds that in this regard, Kōbō Daishi’s statement that, “the Buddha Dharma is nowhere remote. It is in our own mind; it is close to us. Suchness is nowhere external. If not within our body, where can it be found?” and Swedenborg’s statements, “Why do people focus so much on the external? Why do people propagate the Bible over and over again?… Is the lord not within us?” and “it is imprinted onto all humans to look within oneself to perceive the divine entity” all correspond to each other (Dentō 101 [1895]: 10).

Hirai’s influence on Ishidō can be seen in his treatment of “truth” as the foundation for comparison. Like Hirai, Ishidō also cites the poem, “While at the base of the mountain the paths leading upward are many, is it not the same moon in the sky that all see in the end?” and comments: “There is only one cosmic truth; while people of then and now, east and west differ, the ultimate truth cannot but be one, just as they look at the same bright disc of the moon. There exist various methods, however, to reach the source of this truth” (Dentō 100: 12). While it is also possible to see the influence of Unitarianism in these ideas, the influence of Hirai Kinza’s notion of synthetic religion can be felt strongly in the use of the moon as a metaphor for truth. Further, drawing on Emerson, Ishidō stresses the importance of intuition for salvation. Following Swedenborg, intuition can be further divided into the superficial and the profound. Ishidō argues that profound (spiritual) intuition corresponds to what Kōbō Daishi propagated, saying that through this intuition it is possible to see the entire cosmos in a single drop of water (Dentō 100: 13).

Among Ishidō’s contemporaries, there were young intellectuals who made similar arguments concerning the understanding of truth trough intuition. Among intellectuals who were discussing mysticism in the second half of the 1880s to the mid-1890s, Taoka Reiun (1871–1912) is of particular importance. Taoka was known as a literary critic and as an author of pioneering writings about mysticism. He was not only familiar with classical mysticism (German mysticism, Indian Yoga philosophy, Neo-Platonism) and Schopenhauer’s philosophy, but also had detailed knowledge of contemporary European intellectual trends such as Theosophy, Mesmerism, and Vegetarianism.16 In the essay “Beauty and the Good” (Bi to zen 美と善), Taoka wrote that the experience of forgetting the self is “the state where every being is perfect and spiritual enlightenment is without impediment.” Since the existence of “buddhas” or “god” can also be traced back to this subjective psychological state, “Christ and paradise are already inside of you, and Shakyamuni has achieved buddhahood in his very body” (Nishida 1973, 234; first published in Shūkyō 35 [5 September 1895]). He also wrote that the climate of skepticism created by experimental science is overpowering, and that Japan has turned into a state of “no faith and no religion.” However, without faith people cannot live, he writes. To overcome skepticism, the only option is to gain mystical experiences through Zen and to realize that “one should not look for god outside oneself nor should one look for Buddha outside one’s own nature.”17 The emergence of this issue in Japan came with the introduction of Western civilization, but, Taoka prophesized, Western and Eastern civilization were headed towards reconciliation in the twentieth century: “Material civilization was imported to the Orient from the West, but spiritual civilization has not been injected from the Orient to the West. Ah! Will we see in the coming twentieth century the mutual mixing of Eastern and Western civilization and the emergence of a grand new civilization whose light will reach all corners of the world?”18

It is a fact that during the period from the mid-1880s to mid-1890s, Vetterling’s Buddhist Swedenborgianism exerted a great influence on Buddhism. Whether in the case of those who saw Swedenborg as a Buddhist, as Vetterling did (as did Shaku Sōen who will be discussed below), or in the case of those who, like Ishidō Emyō, distinguished between Swedenborg’s philosophy and Buddhism but still compared the two, Swedenborg’s philosophy was widely regarded as very similar to Buddhism. This is not the result of a one-sided imposition of American occultism onto Japan, however, nor of a strategic occidentalist usage, as James Ketelaar (1993) argues. That Ishidō’s comparative framework was that of an amalgamated religion like Heart Learning (Shingaku) and its modernized version in the form of Hirai Kinza’s synthetic religion is the result of active attempts on the Japanese side to absorb this thought. It was also nothing unusual for a young Buddhist such as Daisetsu in the mid-1880s to mid-1890s to be interested in Swedenborg.

Furthermore, discussion of Swedenborg led to a focus on psychological states that went beyond reason and the ordinary senses in the form of samadhi, or intuition. At the same time, Taoka Reiun was already proposing a theory of mystical experience based on religion and a decontextualized theory of Zen experience that was inseparably linked to the former. Considering that Taoka had been a non-regular student at Tokyo Imperial University like Daisetsu, and that he had been a prolific writer in the first half of the 1890s, it can be assumed that Daisetsu knew of Taoka.19 Further, as I argue below, judging by the similarity in content of Daisetsu’s and Ishidō’s writings, there is the possibility that Daisetsu was also familiar with these ideas. That is, the topics that Daisetsu would continue to reflect on—the meaning of the universality of religious truth, the congruence or opposition of Western and Eastern mystical thought, Swedenborg’s philosophy—all had been raised already by other young intellectuals during the period of the mid- 1880s to mid-1890s. In other words, ideas that later came to be criticized as characteristic of Suzuki Daisetsu’s thought (an exclusive emphasis on experience, comparisons of stereotyped Western and Eastern civilization) were already constitutive elements of the Buddhist world of that period without Daisetsu’s help.

Daisetsu and Swedenborg

It is believed that there were three instances in the first half of Suzuki Daisetsu’s life in which he came into contact with Swedenborg‘s philosophy.

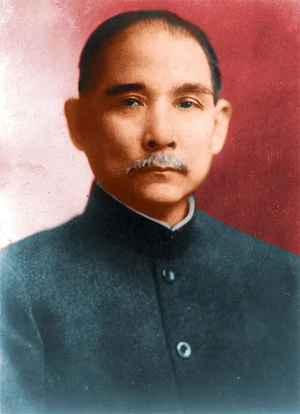

It is possible that Daisetsu learned about Swedenborg through contemporary Buddhist magazines before embarking for America. We know at least that his master Shaku Sōen was familiar with the volume Zuiha Bukkyōgaku. In an “Epigraph” attached to Daisetsu’s partial translation of Paul Carus’ The Gospel of Buddha, published in the eighty-sixth issue of Shimei yoka, he writes:

Even though there are a great number of Western scholars who translate Indian Sanskrit texts or write about Chinese Buddhism, works that have been translated and distributed in our country are limited to those by Mr. Max Müller, A Buddhist Catechism by Mr. Olcott, The Light of Asia by Mr. Arnold, and Buddhist studies (Bukkyōgaku)20 by Mr. Swedenborg.

(Shimei yoka 86 [24 February 1895]: 12)

The fact that Zuiha Bukkyōgaku is mentioned here alongside Müller, Arnold, and Olcott can also be taken to show that Shaku Sōen regarded it as a work on Buddhism, despite knowing its contents.

Furthermore, Daisetsu published a short piece entitled “The Zen of Emerson” in issue 14 of the magazine Zenshū on 1 March 1896. He does not mention Ishidō’s name in it, but its content resembles that of Ishidō’s articles. The way that Daisetsu develops an argument about the unity of all religions based on Zen through a poem that uses the moon as a metaphor is another example of this conflation, as witnessed in the following quote.

Since the so-called paths leading up from the base of the mountain are manifold, somebody who is in one place will look at the reflection of the moon from that position and take that as the truth, while somebody in another place will look at the reflection of the moon from another perspective and take that as the truth. If someone reaches the very top beyond which one can proceed no further, he is already removed from the path of delusion, does not discriminate between this and that, and therefore there is no more quarrel. Therefore, even Confucianism ultimately becomes Zen, and Daoism and Christianity, too, inevitably turn into Zen. (sdz 30: 42)

Or, as shown by the next quote, the emphasis on experience over scriptures reminds one of Ishidō and Taoka:

Concerning Emerson, Daisetsu wrote that, “[Emerson] does not take god to actually exist outside the mind or to be a human-like creator. Correspondingly, he does not employ literal meanings in his understanding of the teachings of Christ, turning the idolatrous Christianity of the past into an intuitive and self-reflective religion. He does not seek god through other languages and scripts, [instead] arguing that if one moves straight ahead and removes the manifold emotions, the spirit will be enriched, and the mind will enter a realm of highest joy (gokuraku). (sdz 30: 49)

As a matter of fact, this interesting philosophy consisting of the idea of the unity of all religions centered on “Zen,” the rejection of a personalized creator god, and an intuitive understanding not dependent on texts had already been formulated at this point, and Ishidō had already used these notions in his own writings. The similarity of Ishidō’s and Daisetsu’s theories of religion does not only derive from Swedenborg’s influence on Emerson, but possibly also from Daisetsu having read Ishidō’s writings (or those of Vetterling). However, it is interesting to note that what Ishidō called “truth” (shinri 真理), Daisetsu called “enlightenment” (satori 悟り). Having said that, all this amounts only to circumstantial evidence, and, as far as can be ascertained, it was only after making his way to America that Daisetsu became interested in Swedenborg. This was probably due to the influence of A. J. Edmunds, whom he met while living there. It has been argued that Daisetsu learned about Swedenborg from Edmunds, who was employed for a short period of time at Open Court in July 1903. This can be ascertained through both Edmunds’ own diary and Daisetsu’s own words.21

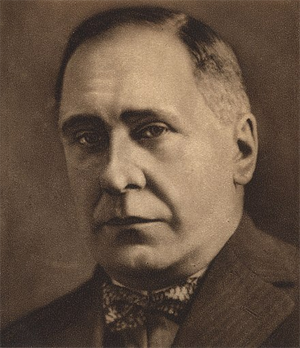

Albert Joseph Edmunds (1857–1941) has already been mostly forgotten, but he was a “Buddhist” who in many points resembled Vetterling. He was born in 1857 into a family of Quakers in England and immigrated to America in 1885. He moved to Philadelphia, a Quaker stronghold, becoming a cataloger for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and spent the rest of his life there. A scholar of Buddhism, Edmunds co-authored, together with Anesaki Masaharu, a work comparing Buddhism and Christianity (Edmunds 1905), while spending a quiet life as librarian for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Besides research on Buddhism, he also tried his hand at research on early Christianity and penned an anthology of poems (Leonard 1908, 230). Despite being a Quaker, he was a Swedenborgian and vegetarian. It is unclear, though, how Edmunds and Vetterling stood towards each other, and it should be pointed out that this combination of Buddhism and Swedenborgianism was not exceptional.22

The third instance of contact with Swedenborg came in 1909, when Daisetsu visited London on his way back to Japan from America. On that occasion, on commission from the Swedenborg Society, he fashioned a translation of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell for the purpose of proselytization in Japan. In the summer of 1912 he visited London at the invitation of the Swedenborg Society, translating a further three of Swedenborg’s works. After this, the Japan Swedenborg Society was launched with his participation, 23 and he became involved in publishing these works. However, the activities of the Japan Swedenborg Society seem to have ended in 1915 with the publication of Divine Providence (Shinryoron 神慮論), the conclusion of its publishing contract with the Swedenborg Society in Britain. At the time that Daisetsu began work on his translation, Swedenborg was no longer wrongly regarded as a Buddhist, but Buddhists had also ceased to read and discuss his philosophy. The target audience Daisetsu sought to familiarize with Swedenborg’s philosophy, then, were not Buddhist priests and believers as had been the case when Hirai and Ishidō were writing in the mid- 1880s to mid-1890s, nor was it the young intellectuals (as had been the case with Taoka), but rather the wider general public.

Daisetsu and the Swedenborgians

Apart from the translations, Daisetsu did not pen many other writings about Swedenborg, although he held Swedenborg fundamentally in high regard. Daisetsu’s collected thoughts on Swedenborg are expressed in a lecture he gave at the Swedenborg Society, which is included in the Society’s 1912 Annual Report. The lecture is divided into three parts, the first dealing with the allure of Swedenborg, the second with the spread of his philosophy in Japan, and the last with Japan’s spiritual poverty as well as Daisetsu’s expectations for its recovery via Swedenborg’s thought. Spread across these three parts is an analysis of Japan’s spiritual culture and a discussion of the transmission of Swedenborg’s philosophy. With regard to its content, it can be called the antetype of later discussions of Swedenborg, but its unadulterated praise and expressions are rarely seen in Japanese writings.24

First, Daisetsu praises Swedenborg’s writing style in the following terms:

Even his peculiar repetitious style of writing is so characteristic of him. It is so much like a grey-haired, long-bearded, kind-looking, patriarchal wise man teaching his children, who gather about him and wonderingly listen to what he says about the wonders of an unknown world. He has naturally to repeat over again and again lest his ignorant audience should miss his heavenly message—he has so much to say, and all so new to his listeners. In his style I perceive the kindly heart of the author, and in the matter of his writing I perceive his intellectual penetration and deep spiritual insight into the secrets of life. (aars, 31)

Next, he makes an interesting argument regarding the need for Swedenborg’s philosophy in Japan.

A senior friend of mine who is the chief prosecuting attorney in the supreme Court of Japan is a religiously minded person—and he was one of the first who bought the Japanese copies of Heaven and Hell. When I met him later, he was enthusiastic about the book, and highly recommended it to the Japanese public, which is lately, I am sorry to say, losing faith in the world to come, or rather in a world which exists along with this one. He ascribed one of the reasons why crime seems to be growing rampant lately in Japan, to the lack of the knowledge of a coming life. (aars, 32)

Here, Daisetsu introduces the concept of the loss of belief in the afterlife or other world (that is, Japan’s modernization) and the idea that enlightenment thought has invited moral decay. These notions also reflect his own opinions. His conclusion is a rather vicious critique of Japan:

There was a time once when everything spiritual was hopelessly trodden under foot and most contemptuously looked upon as having nothing to do with material welfare, political reformation, industrial prosperity, or, in short, with the development of the national life. This was when materialism was at its height, which came soon after the political revolution about forty years ago. This revolution or reformation destroyed everything historical, priding itself in this very destruction. Old Japan was to go, and New Japan to be welcomed at any cost. But the fact is that we cannot live without history. We are all historical. We grow out of the historical background. New Japan must be the continuous growth of Old Japan. And Old Japan was religious and spiritual, as you can see from the numerous temples, monasteries, and shrines still in existence. Swedenborg, too, must come and help New Japan to be placed once more upon the solid pedestal of spirituality. In concluding this, I wish to express my gratitude for your having made it possible for me to peruse Swedenborg with thoroughness, which has opened to me so many beautiful, noble things belonging to the spirit. My next task will be to purify my own will through this elevated understanding and thus to appreciate his wonderful message spiritually. (aars, 33–34)

By comparison, in Suedenborugu, the representative treatise on Swedenborg in Japanese, Daisetsu gave an overall very positive evaluation of Swedenborg despite some criticism, writing that, “despite the fact that not all that [Swedenborg] wrote can be believed, there are pearls among the rubble” (sdz 24: 11. From Suedenborugu).