Gyalo Thondup

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/26/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

When the United States learned that the Dalai Lama had gotten permission in early November to attend the Buddha Jayanti celebrations, the CIA scrambled to bypass Sikkim and establish direct links with Tibetan sources close to the monarch.

None were closer than the Dalai Lama's two brothers in exile. The eldest, Thubten Norbu, already had a history of indirect contact with the agency via the Committee for a Free Asia… Settling in New Jersey, Norbu began to earn a modest income teaching Tibetan to a handful of students as part of a noncredited course at Columbia University.

The other brother, Gyalo Thondup, was residing in Darjeeling. Six years Norbu's junior, Gyalo was the proverbial prodigal son… As a teen, he had befriended members of the Chinese mission in Lhasa and yearned to study in China… Gyalo got his wish in 1947 when he and a brother-in-law arrived at the Kuomintang capital of Nanking and enrolled in college.

Two years later, Gyalo, then twenty-one, veered further toward China when he married fellow student Zhu Dan. Not only was his wife ethnic Chinese, but her father, retired General Chu Shi- kuei, had been a key Kuomintang officer during the early days of the republic. Because of both his relationship to General Chu and the fact that he was the Dalai Lama's brother, Gyalo was feted in Nanking by no less than Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek…

With the communists closing in on Nanking during the final months of China's civil war, Gyalo and his wife fled in mid-1949 to the safer climes of India. Once again because of his relationship to the Dalai Lama, he was added to the invitation list for various diplomatic events and even got an audience with Prime Minister Nehru.

That October, Gyalo briefly ventured to the Tibetan enclave at Kalimpong before settling for seven months in Calcutta. While there, his father-in-law, General Chu, attempted to make contact with the Tibetan government. With the retreat of the Kuomintang to Taiwan, Chu had astutely shifted loyalty to the People's Republic and was now tasked by Beijing to arrange a meeting between Tibetan and PRC officials at a neutral site, possibly Hong Kong.

Conversant in Chinese and linked to both the Dalai Lama and General Chu, Gyalo was a logical intermediary for the Hong Kong talks… Unable to gain quick entry to the crown colony, Gyalo made what he intended to be a brief diversion to the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan. But Chiang Kai- shek, no doubt anxious to keep Gyalo away from General Chu and the PRC, had other plans. Smothering the royal sibling with largesse, Chiang kept Gyalo in Taipei for the next sixteen months. Only after a desperate letter to U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson requesting American diplomatic intervention did the ROC relent and give Gyalo an exit permit.

After arriving in Washington in September 1951, Gyalo continued to dabble in diplomacy. Within a month of his arrival, he was called to a meeting at the State Department. Significantly, Gyalo's Chinese wife was at his side during the encounter. Because of the couple's close ties to Chiang, department representatives assumed that details of their talk would quickly be passed to the Kuomintang Nationalists…

Despite State Department efforts to secure him a scholarship at Stanford University, he hurriedly departed the United States in February 1952 for the Indian subcontinent. Leaving his wife behind, he then trekked back to Lhasa after a six-year absence.

By that time, Beijing had a secure foothold in the Tibetan capital. Upon meeting this wayward member of the royal family, the local PRC representatives were pleased. As a Chinese speaker married to one of their own, Gyalo was perceived as a natural ally. Yet again, however, he would prove a disappointment. After showing some interest in promoting a bold land reform program championed by the Dalai Lama, Gyalo once more grew restive. In late spring, he secretly met with the Indian consul in Lhasa, and after promising to refrain from politicking, he was given permission to resettle in India…

Noting his recent return to Darjeeling, the U.S. embassy in early August 1952 cautiously considered establishing contact. Calcutta's Consul General Gary Soulen saw an opportunity in early September while returning from his Sikkim trek with Princess Kukula. Pausing in Darjeeling, Soulen stayed long enough for Gyalo to pass on the latest information from his contacts within the Tibetan merchant community.

Although he had promised to refrain from exile politics, Gyalo saw no conflict in courting senior Indian officials. In particular, he sought a meeting with India's spymaster Bhola Nath Mullik. As head of Indian intelligence, Mullik presided over an organization with deep colonial roots. Established in 1887 as the central Special Branch, it had been organized by the British to keep tabs on the rising tide of Indian nationalism. Despite several redesignations before arriving at the title Intelligence Bureau, anticolonialists remained its primary target for the next sixty years.

Upon independence in 1947, Prime Minister Nehru appointed the bureau's first Indian director…

Three years later, Mullik became the bureau's second director. A police officer since the age of twenty-two, the taciturn Mullik was known for his boundless energy (he often worked sixteen-hour days), close ties to Nehru, healthy suspicion of China, and (rare for a senior Indian official) predisposition against communism. Almost immediately, the Tibetan frontier became his top concern. This followed Beijing's invasion of Kham that October, which meant that India's military planners now had to contend with a hypothetical front besides Pakistan. Moreover, the tribal regions of northeastern India were far from integrated, and revolutionaries in those areas could now easily receive Chinese support. The previous year, in fact, the bureau had held a conference on risks associated with Chinese infiltration.

Despite Mullik's concerns, Nehru was prone to downplay the potential Chinese threat. Not only did he think it ludicrous to prepare for a full-scale Chinese attack, but he saw real benefits in cultivating Beijing to offset Pakistan's emerging strategy of anticommunist cooperation with the West. "It was Nehru's idealism against hard-headed Chinese realism," said one Intelligence Bureau official. "Mullik injected healthy suspicions."

Astute enough to hedge his bets, Nehru allowed Mullik some leeway in improving security along the border and collecting intelligence on Chinese forces in Tibet. To accomplish this, Mullik expanded the number of Indian frontier posts strung across the Himalayas. In addition, he sought contact with Tibetans living in the Darjeeling and Kalimpong enclaves. Not only could these Tibetans be tapped for information, but a symbolic visit by a senior official like Mullik would lift morale at a time when their homeland was being subjugated. Such contact, moreover, could give New Delhi advance warning of any subversive activity in Tibet being staged from Indian soil.

Of all the Tibetan expatriates, Mullik had his eye on Gyalo Thondup. Besides having an insider's perspective of the high offices in Lhasa, Gyalo had already passed word of his desire for a meeting. Prior to his departure for his first visit to Darjeeling in the spring of 1953, Mullik asked for -- and quickly received -- permission from the prime minister to include the Dalai Lama's brother on his itinerary. Their subsequent exchange of views went well, as did their tete-a-tete during Mullik's second visit to Darjeeling in 1954…

To earn a living, [Gyalo] ironically began exporting Indian tea and whiskey to Chinese troops and administrators in Tibet. For leisure, he and his family were frequent guests at the Gymkhana Club. Part of an exclusive resort chain that was once a playpen for the subcontinent's colonial elite, the Gymkhana's Darjeeling branch was situated amid terraced gardens against the picturesque backdrop of Kanchenjunga. A regular on the tennis courts, the Dalai Lama 's brother was the local champion.

In the summer of 1956, Gyalo's respite came to an abrupt end. The senior abbot and governor from the Tibetan town of Gyantse had recently made his escape to India and in July wrote a short report about China's excesses. Gyalo repackaged the letter in English and mailed copies to the Indian media, several diplomatic missions, and selected world leaders. One of these arrived in early September at the U.S. embassy in the Pakistani capital of Karachi, and from there was disseminated to the American mission in New Delhi and consulate in Calcutta…

Once word reached India in early November that the Dalai Lama would be attending the Buddha Jayanti, John Hoskins got an urgent cable from headquarters. Put aside your efforts against the Chinese community, he was told, and make immediate contact with Gyalo. A quick check indicated Gyalo's predilection for tennis, so Hoskins got a racket and headed north to Darjeeling. After arranging to get paired with Gyalo for a doubles match, the CIA officer wasted no time in quietly introducing himself…

Hoskins was not exactly wowed by Gyalo's persona. "There was a lot of submissiveness rather than dynamism," he noted. At their first meeting, little was discussed apart from reaching an understanding that, to avoid Indian intelligence coverage in Darjeeling, future contact would be made in Calcutta using proper countersurveillance measures.

Later that same month, the Dalai Lama and a fifty-strong delegation departed Lhasa by car. Switching to horses at the Sikkimese border, the royal entourage was met on the other side by both Gyalo and Norbu, who had rushed to India from his teaching assignment in New York. The party was whisked through Gangtok and down to the closest Indian airfield near the town of Siliguri, and by 25 November the monarch was being met by Nehru on the tarmac of New Delhi's Palam Airport.

By coincidence, three days after the Dalai Lama's arrival in New Delhi, Chinese premier Zhou En-Lai began a twelve-day stop in India as part of a five-country South Asian tour. Keeping with diplomatic protocol, the young Tibetan leader was on hand to greet Zhou at the airport. The two then held a private meeting, at which time the elderly Chinese statesman lectured the Dalai Lama on the necessity of returning to his homeland.

Zhou was not alone in his appeal. As eager as Nehru was to offset Chinese influence in Tibet, he, too, was against the Dalai Lama's seeking asylum -- especially on Indian soil. This was partly because India wanted to maintain good relations with China. This was also because New Delhi did not want to go it alone, and not a single country to date had recognized Tibetan independence. Fearing that the monarch's brothers would have an unhealthy effect on any decision, Indian officials in the capital did all in their power to keep Gyalo and Norbu segregated from their royal sibling.

The Dalai Lama hardly needed convincing from his brothers, however. During his first private session with Nehru, he openly hinted about not going back to Lhasa. He also requested that the issue of Tibetan independence be taken up by Nehru and President Dwight Eisenhower at their upcoming summit in Washington in December. Nehru was not entirely surprised by all this: Gyalo had already sought out Mullik and told the Indian intelligence chief in no uncertain terms that his brother would opt for exile.

As India's leadership digested these developments, the Dalai Lama departed the capital for an exhausting schedule of Buddha Jayanti festivities. He was still in the midst of this tour when Zhou returned to New Delhi for an encore visit on 30 December. In the interim, Nehru had had his Washington meeting with Eisenhower, and the Chinese premier had scheduled the stop specifically to discuss the outcome of that summit. As it turned out, however, Tibet was a major topic of conversation. In particular, Nehru used the opportunity to press Zhou about tempering China's harsh military and agrarian policies on the Tibetan plateau…

Anxious to broker a deal that would assuage both Lhasa and Beijing, Nehru summoned the Dalai Lama from his pilgrimage and underscored to the Tibetan leader that Indian asylum was not in the cards. But if that was bitter news, Zhou had earlier proposed a sweetener. While noting that China was ready to use force to stamp out resistance, he claimed that Mao now recognized the folly of rapid collectivization and pledged to delay further revolutionary reforms in Tibet.

Zhou and his senior comrades were by now gravely concerned over permanently losing the Dalai Lama. Leaving nothing to chance, Zhou was back in New Delhi on 24 January 1957 for his third visit in as many months.

Despite Beijing's lobbying, Gyalo and Norbu were still insistent that their brother choose exile. Torn over his future, the twenty-one-year-old monarch had already departed Calcutta on 22 January for Kalimpong, which by then was home to a growing number of disaffected Tibetan elite. Once there, he did what Tibet's leaders had done countless other times when confronted with a hard decision: he consulted the state oracle. Two official soothsayers happened to be traveling with his delegation; using time-honored -- if unscientific -- methods, the pair went into a trance on cue and recited their sagely advice. Return to Lhasa, they channeled.

As far as the Dalai Lama was concerned, the ruling of his oracles was incontrovertible, and the decision was made all the easier by the fact that nobody seemed anxious to give him refuge. Flouting the suggestions of his brothers, he declared his intention to go home. He crossed into Sikkim in early March and was compelled to remain in Gangtok until heavy snows melted from the mountain passes. There, he finalized plans to set out for Lhasa by month's end…

[A]s soon as the Dalai Lama received permission to attend the Buddha Jayanti, [William] Broe [CIA China Branch] felt it prudent to show heightened interest. Looking for a junior officer to spare, he soon settled on John Reagan. Twenty-eight years old, Reagan had joined the agency upon graduation from Boston College in 1951. He was soon in Asia, where he spent the next twenty-four months working on paramilitary projects in Korea. Switching to China Branch, he served two more years in Japan as part of the CIA's penetration effort against the PRC. Returning to the United States in 1955, Reagan divided the next twelve months between Chinese language training and trips to New York City to practice tradecraft against United Nations delegates.

As the branch's new man on Tibet, Reagan initially did little more than forward instructions for John Hoskins to make contact with Gyalo. He was silent on further guidance, primarily because senior U.S. policy makers had not yet ironed out a coherent framework for dealing with Lhasa. In earlier meetings between CIA and State Department officials during the summer of 1956, there had been those who felt that the Dalai Lama should flee to another Buddhist nation to offer a rallying cry for anticommunist Buddhists across Asia. Others, primarily inside the agency, believed that he could play a more important role as a rallying symbol in Lhasa among his fellow Tibetans. This was still the CIA's operating assumption in late 1956: once the Dalai Lama was in India, the prevailing mood at agency headquarters was that he should eventually go home.

Gyalo, meantime, was telling Hoskins that his brother had every intention of seeking asylum. With the Dalai Lama apparently intent on staying away from his homeland -- and therefore not conforming to the agency's preferred scenario of rallying his people from Lhasa -- Reagan was largely idle during most of the Dalai Lama's four-month absence from Tibet.

Eventually, however, the CIA looked to hedge its bets. Since the second half of 1956, a band of twenty-seven young Khampa men -- some still in their late teens -- had been growing restive in the enclave of Kalimpong. Most came from relatively wealthy trading families and had been spirited to India to protect them from the instability in their native province. Full of vigor, the entire group had ventured to New Delhi shortly before the Dalai Lama's Buddha Jayanti pilgrimage to conduct street protests. Once the Dalai Lama arrived, they sought a brief audience to make an impassioned plea for Lhasa's intercession against the Chinese offensive in Kham.

To their disappointment, the Dalai Lama counseled patience. "His Holiness only said things would settle down," recalls one of the Khampas. Undaunted, the twenty-seven young men shadowed the monarch during several of the Buddha Jayanti commemorative events. By early January 1957, this took them to Bodh Gaya, the city in eastern India where the historical Buddha was said to have attained enlightenment. While there, the Dalai Lama's older brother, Thubten Norbu, approached the Khampas and asked if he could take their individual photographs as a souvenir. Although it was an odd request, they complied.

For the next few weeks, nothing happened. Frustrated by the Dalai Lama's repeated rebuffs, the Khampas sulked back to Kalimpong. Several Chinese traders were in town, some of whom were rumored to have links to the Nationalist regime on Taiwan. Desperate, the Khampas sounded them out on the possibility of covert assistance from Taipei. It was at that point that Gyalo Thondup arrived and requested a meeting with all twenty-seven. For most of the young Khampas, it was the first time they had spoken with the Dalai Lama's lay brother. As they listened attentively, Gyalo lectured them to steer clear of the Kuomintang. "The United States," he told them cryptically, "is a better choice."

Less than a week later, the Dalai Lama arrived in Kalimpong, the oracles had their channeling session, and things changed dramatically. With the monarch's return journey now imminent, John Reagan in Washington scrambled to script a program of action. At its core, the plan called for a unilateral capability to determine how much armed resistance activity really existed in Tibet; further commitments could then be weighed accordingly.

The CIA had good reason to act with prudence. It already had a long and growing list of embarrassing failures while working with resistance groups behind communist lines. Perhaps none had been more painful than its experience against the PRC. There the agency's efforts had taken two tracks. The first was a collaborative effort with the Kuomintang government on Taiwan. Clinging to its dream of reconquering the mainland, the ROC in 1950 claimed to control a million guerrillas inside the People's Republic. Although a February 1951 Pentagon study placed the figure at no more than 600,000 -- only half of which were thought to be nominally loyal to the ROC -- Washington saw fit to support these insurgents as a means of appeasing a key Asian ally while at the same time possibly diverting Beijing's attention from the conflict on the Korean peninsula.

To funnel covert American assistance to the ROC, the CIA established a shell company in Pittsburgh known as Western Enterprises (WE). In September 1951, WE's newly appointed chief, Raymond Peers, arrived on Taiwan with a planeload of advisers. A U.S. Army colonel who had earned accolades during World War II as chief of the famed OSS Detachment 101 in Burma, Peers quickly initiated a number of paramilitary efforts. A large portion of his resources was directed toward airborne operations, including retraining the ROC's 1,500-man parachute regiment. Other WE advisers, meanwhile, were tasked with putting ROC action and intelligence teams through an airborne course.

To deploy these operatives, WE turned to the agency's Far East air proprietary, Civil Air Transport (CAT). By the spring of 1952, CAT planes were dropping teams and singletons on the mainland, as well as supplies to resistance groups that the ROC claimed were already active on the ground. Some of the penetrations ranged as far as Tibet's Amdo region, where the ROC alleged it had contact with Muslim insurgents.

Concurrently, the agency in April 1951 initiated a unilateral third-force effort using anticommunist Chinese unaffiliated with the ROC. Allocated enough arms and ammunition for 200,000 guerrillas, the CIA recruited many of these third-force operatives from Hong Kong, trained them in Japan and Saipan, and inserted them in CAT planes via air bases in South Korea…

That summer, an armistice sent the Korean conflict into remission. This provided the CIA with convenient cover to reassess its third-force track. Although it elected to maintain a China Base at Yokosuka, Japan, this unit was to handle primarily agent penetrations and low-level destabilization efforts; support for broader unilateral resistance got the ax.

Cooperative ventures with the ROC were not so easily nixed. Although Taipei had tempered its claims somewhat, it still pegged loyal mainland guerrilla strength at 650,000 insurgents. By contrast, a November 1953 estimate by the U.S. National Security Council (NSC) put the figure closer to 50,000. Despite this huge discrepancy, the NSC still advocated continued covert assistance to the ROC in order to develop anticommunist guerrillas for resistance and intelligence. Even temporary guerrilla successes, the council reasoned, might set off waves of defections and stiffen passive resistance.

Chiang Kai-shek could not have agreed more. Eager to vastly increase the scope of guerrilla support, the generalissimo in 1954 asked Washington for some 30,000 parachutes. Turned down the first time, he made further high-priority appeals over the next two years. These parachutes were needed for an ambitious plan to drop 100-man units near major PRC population centers. Hoping to set off a chain of uprisings, Chiang optimistically talked in terms of uprooting Chinese communism in as little as two years.

Hearing these plans, Washington patiently counseled against the proposed airborne blitz. On a more modest level, however, the CIA's assistance program continued unabated. In this, success was more elusive than ever. Despite inserting an average of two Nationalist agents a month through the mid-1950s, the ROC operatives were still being killed or captured in short order.

Although these reasons might have made covert operations against the PRC a study in frustration, Tibet appeared to be different. Unlike many of Taipei's wishful claims about other areas of the mainland, Tibet had a resistance movement corroborated by multiple, albeit dated, sources. What the CIA needed was timely data that could give a current and accurate picture of this resistance. And given the historical animosity between Tibetans and lowland Chinese, the agency needed to gather this information without resort to ROC assistance.

In February 1957, John Hoskins was ordered by Washington to immediately identify eight Tibetan candidates for external training as a pilot team that would infiltrate their homeland and assess the state of resistance. Gyalo, who had been in Kalimpong making an eleventh-hour bid to convince his brother to seek asylum, was given responsibility for screening candidates among the Tibetan refugees already in India. Although the twenty-seven Khampas did not know it, Gyalo intended to make the selection from their ranks. Using the photographs taken by Norbu at Bodh Gaya, he sought guidance from two senior Khampas in town, both of whom hailed from the extended family of Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang, a prominent trader of Tibetan wool, deer horns, and musk.

With their assistance, Gyalo soon settled on his first pick. Wangdu Gyato-tsang, age twenty-seven, had been born to an affluent Khampa family from the town of Lithang. He was well connected: Gompo Tashi was his uncle, as was one of the senior Khampas helping Gyalo with the selection. Wangdu also had the right disposition for the task at hand. Despite being schooled at the Lithang monastery from the age of ten, he did not exactly conform to monastic life. "He was hot tempered from childhood," recalls younger brother Kalsang...

When approached by Gyalo, Wangdu immediately volunteered for the mission. Within days, five other Khampas were singled out (Washington now wanted a total of six trainees, not eight), but only Wangdu was given any hint of the impending assignment. Four were from Lithang; of these, three were Wangdu's close acquaintances, and one was his family servant. The fifth was a friend from the nearby town of Bathang (also spelled Batang). All were still on hand to attend the Dalai Lama's final open-air blessing in a Kalimpong soccer field shortly before the monarch headed back toward Tibet.

-- The CIA's Secret War in Tibet, by Kenneth Conboy and James Morrison

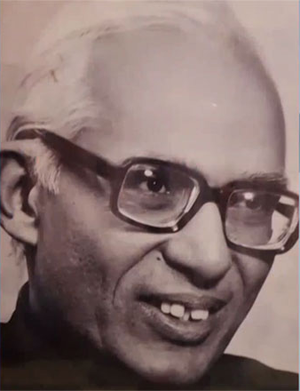

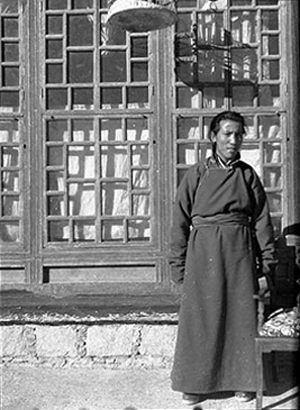

Gyalo Thondup

Gyalo Thondup in 1948 or 1949, standing in front of a large window of the Dalai Lama's family house, Yabshi Taktser, in Lhasa. He is wearing a woollen robe and felt boots. The bottom part of a bird cage can be seen at the top of the image.

Gyalo Thondup (Tibetan: རྒྱལ་ལོ་དོན་འགྲུབ, Wylie: rgyal lo don 'grub; Chinese: 嘉乐顿珠; pinyin: Jiālè Dùnzhū), born c.1927,[1] is the second-eldest brother of the 14th Dalai Lama. He often acted as the Dalai Lama's unofficial envoy, and was involved in various political controversies around the Tibetan diaspora.[2]

Early life

In late fall of 1927,[1] Gyalo Thondup was born in the village of Taktser[3] Ping'an District, Qinghai province. In 1939, he moved with his family to Lhasa.

In 1942, at the age of 14, Thondup went to Nanjing, the capital of Republican China, to study Standard Chinese and the history of China. He often visited Chiang Kai-shek at his home and ate dinner with him.[4] "In fact, young Gyalo Thondup ate his meals at the Chiang family table, from April 1947 until the summer of 1949, and tutors selected by Chiang educated the boy."[5] In 1948, he married Zhu Dan, the daughter of a Guomindang general.

Political involvement

In 1949, before the Communist revolution of that year in China, Thondup left Nanjing for India via British Hong Kong. "Gyalo Thondup... was the first officially acknowledged Tibetan to visit Taiwan since 1949. Taipei Radio announced the meeting between President Chang Kai-shek on 21 May 1950."[6] Fluent in Chinese, Tibetan and English,[5] he "later facilitated semi-official contacts between the Tibetan-government-in-exile and the Republic of China (ROC) as well as with the People's Republic of China (PRC) government in 1979."[6]