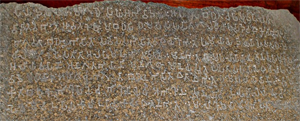

William Jones (philologist)by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/10/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. I, 1799.-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. II, 1799.-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. III, 1799.-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. IV, 1799.-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. V, 1799.-- The Works of Sir William Jones. In Six Volumes. Vol. VI, 1799.-- Sacontala [Shakuntala]; or, The Fatal Ring: An Indian Drama, by Calidas [Kalidasa], Translated from the Original Sanscrit and Pracrit by Sir William Jones-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones-- Manusmriti, by Wikipedia

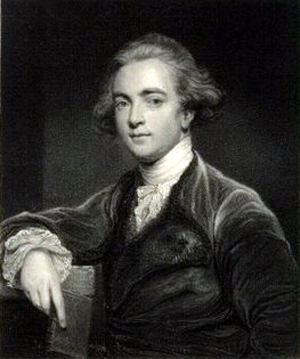

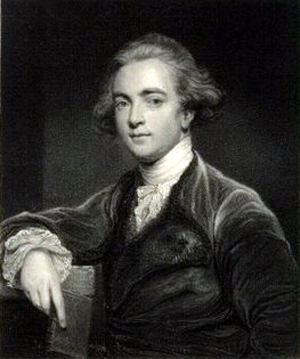

William Jones

A steel engraving of Sir William Jones, after a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds

Puisne judge of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal

In office: 22 October 1783[1] – 27 April 1794[2]

Personal details

Born: September 28, 1746, Westminster, London

Died: April 27, 1794 (aged 47), Calcutta

Sir William Jones FRS FRSE (28 September 1746 – 27 April 1794) was an Anglo-Welsh philologist, a puisne judge on the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Bengal, and a scholar of ancient India, particularly known for his proposition of the existence of a relationship among European and Indian languages, which he coined as Indo-European.Jones is also credited for establishing the Asiatic Society of Bengal in the year 1784.

BiographyWilliam Jones was born in London at Beaufort Buildings, Westminster; his father William Jones (1675–1749) was a mathematician from Anglesey in Wales, noted for introducing the use of the symbol π. The young William Jones was a linguistic prodigy, who in addition to his native languages English and Welsh,[3] learned Greek, Latin, Persian, Arabic, Hebrew and the basics of Chinese writing at an early age.[4] By the end of his life he knew eight languages with critical thoroughness, was fluent in a further eight, with a dictionary at hand, and had a fair competence in another twelve.[5]Jones' father died when he was aged three, and his mother Mary Nix Jones raised him. He was sent to Harrow School in September 1753 and then went on to University College, Oxford. He graduated there in 1768 and became M.A. in 1773. Financially constrained, he took a position tutoring the seven-year-old Lord Althorp, son of Earl Spencer. For the next six years he worked as a tutor and translator. During this time he published Histoire de Nader Chah (1770), a French translation of a work originally written in Persian by Mirza Mehdi Khan Astarabadi. This was done at the request of King Christian VII of Denmark: he had visited Jones, who by the age of 24 had already acquired a reputation as an orientalist. This would be the first of numerous works on Persia, Turkey, and the Middle East in general.

Tomb of William Jones in CalcuttaIn 1770, Jones joined the Middle Temple and studied law for three years, a preliminary to his life-work in India. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 30 April 1772. After a spell as a circuit judge in Wales, and a fruitless attempt to resolve the conflict that eventually led to the American Revolution in concert with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, he was appointed puisne judge to the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Calcutta, Bengal on 4 March 1783, and on 20 March he was knighted.

Tomb of William Jones in CalcuttaIn 1770, Jones joined the Middle Temple and studied law for three years, a preliminary to his life-work in India. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 30 April 1772. After a spell as a circuit judge in Wales, and a fruitless attempt to resolve the conflict that eventually led to the American Revolution in concert with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, he was appointed puisne judge to the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William in Calcutta, Bengal on 4 March 1783, and on 20 March he was knighted. In April 1783 he married Anna Maria Shipley, the eldest daughter of Dr. Jonathan Shipley, Bishop of Llandaff and Bishop of St Asaph. Anna Maria used her artistic skills to help Jones document life in India. On 25 September 1783 he arrived in Calcutta.

Jones was a radical political thinker, a friend of American independence. His work, The principles of government; in a dialogue between a scholar and a peasant (1783), was the subject of a trial for seditious libel after it was reprinted by his brother-in-law William Shipley.

In the Subcontinent he was entranced by Indian culture, an as-yet untouched field in European scholarship, and on 15 January 1784 he founded the

Asiatic Society in Calcutta[3] and started a journal called Asiatick Researches.

He studied the Vedas with Rāmalocana, a pandit teaching at the Nadiya Hindu university, becoming a proficient Sanskritist.[3] Jones kept up a ten-year correspondence on the topic of jyotisa or Hindu astronomy with fellow orientalist Samuel Davis.[6] He learnt the ancient concept of Hindu Laws from Pandit Jagannath Tarka Panchanan.[7]

Over the next ten years he would produce a flood of works on India, launching the modern study of the subcontinent in virtually every social science. He also wrote on the local laws, music, literature, botany, and geography, and made the first English translations of several important works of Indian literature.

Sir William Jones sometimes also went by the nom de plume Youns Uksfardi (یونس اوکسفردی, "Jones of Oxford"). This pen name can be seen on the inner front cover of his Persian Grammar published in 1771 (and in subsequent editions).

He died in Calcutta on 27 April 1794 at the age of 47 and is buried in South Park Street Cemetery.[8]

Scholarly contributionsJones is known today for making and propagating the observation about relationships between the Indo-European languages.

In his Third Anniversary Discourse to the Asiatic Society (1786) he suggested that Sanskrit, Greek and Latin languages had a common root, and that indeed they may all be further related, in turn, to Gothic and the Celtic languages, as well as to Persian.[9] Although his name is closely associated with this observation, he was not the first to make it. In the 16th century, European visitors to India became aware of similarities between Indian and European languages[10] and as early as 1653 Van Boxhorn had published a proposal for a proto-language ("Scythian") for Germanic, Romance, Greek, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic and Iranian.[11] Finally, in a memoir sent to the French Academy of Sciences in 1767 Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, a French Jesuit who spent all his life in India, had specifically demonstrated the existing analogy between Sanskrit and European languages.[12][13] In 1786 Jones postulated a proto-language uniting Sanskrit, Iranian, Greek, Latin, Germanic and Celtic, but in many ways his work was less accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included Egyptian, Japanese and Chinese in the Indo-European languages, while omitting Hindustani[11] and Slavic[14]

Nevertheless, Jones' third annual discourse before the Asiatic Society on the history and culture of the Hindus (delivered on 2 February 1786 and published in 1788) with the famed "philologer" passage is often cited as the beginning of comparative linguistics and Indo-European studies.[15]

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

This common source came to be known as Proto-Indo-European.[16]

Jones was the first to propose a racial division of India involving an Aryan invasion but at that time there was insufficient evidence to support it. It was an idea later taken up by British administrators such as Herbert Hope Risley but remains disputed today.[17]

Jones also propounded theories that might appear peculiar today but were less so in his time. For example,

he believed that Egyptian priests had migrated and settled down in India in prehistoric times. He also posited that the Chinese were originally Hindus belonging to the Kshatriya caste.[18]Jones, in his 1772 ‘Essay on the Arts called Imitative’, was one of the first to propound an expressive theory of poetry, valorising expression over description or imitation: “If the arguments, used in this essay, have any weight, it will appear, that the finest parts of poetry, musick, and painting, are expressive of the passions...the inferior parts of them are descriptive of natural objects”.[19] He thereby anticipated Wordsworth in grounding poetry on the basis of a Romantic subjectivity.[20]

Jones was a contributor to Hyde's Notebooks during his term on the bench of the Supreme Court of Judicature. The notebooks are a valuable primary source of information for life in late 18th century Bengal and are the only remaining source for the proceedings of the Supreme Court.

Encounter with Anquetil duperronIn Europe a discussion as to the authenticity of the work of first translation of Avesta arose. It was the first evidence of an indo-european language as old as sanskrit that had been translated into a european language. It was suggested that the so-called Zend-Avesta was not the genuine work of

Zoroaster, but was a forgery. Foremost among the detractors, it is to be regretted, was the distinguished Orientalist, Sir William Jones. He claimed, in a letter published in French (1771), that Anquetil had been duped, that the Parsis of Surat had palmed off upon him a conglomeration of worthless fabrications and absurdities. In England, Sir William Jones was supported by Richardson and Sir John Chardin; in Germany, by Meiners. Anquetil du Perron was labelled an impostor who had invented his own script to support his claim.[21] It is not curious that Jones didn't include Iranian in his naming the cluster of indoeuropean languages, especially since he hadn't any idea about the relationship between avestan and sanskrit as the two main branches of this language family.

Chess poemIn 1763, at the age of 17, Jones wrote the poem Caissa, based on a 658-line poem called "Scacchia, Ludus" published in 1527 by Marco Girolamo Vida, giving a mythical origin of chess that has become well known in the chess world. This poem he wrote in English.

In the poem the nymph Caissa initially repels the advances of Mars, the god of war. Spurned, Mars seeks the aid of the god of sport, who creates the game of chess as a gift for Mars to win Caissa's favour. Mars wins her over with the game.

Caissa has since been characterised as the "goddess" of chess, her name being used in several contexts in modern chess playing.

Schopenhauer's citationArthur Schopenhauer referred to one of Sir William Jones's publications in §1 of

The World as Will and Representation (1819). Schopenhauer was trying to support the doctrine that "everything that exists for knowledge, and hence the whole of this world, is only object in relation to the subject, perception of the perceiver, in a word, representation." He quoted Jones's original English:

... how early this basic truth was recognized by the sages of India, since it appears as the fundamental tenet of the Vedânta philosophy ascribed to Vyasa, is proved by Sir William Jones in the last of his essays: "On the Philosophy of the Asiatics" (Asiatic Researches, vol. IV, p. 164): "The fundamental tenet of the Vedânta school consisted not in denying the existence of matter, that is solidity, impenetrability, and extended figure (to deny which would be lunacy), but in correcting the popular notion of it, and in contending that it has no essence independent of mental perception; that existence and perceptibility are convertible terms."

Schopenhauer used Jones's authority to relate the basic principle of his philosophy to what was, according to Jones, the most important underlying proposition of Vedânta. He made more passing reference to Sir William Jones's writings elsewhere in his works.

Oration by Hendrik Arent HamakerIn 1822 the Dutch orientalist Hendrik Arent Hamaker accepted a professorship at the University of Leiden, and gave as his inaugural lecture in Latin De vita et meritis Guilielmi Jonesii (Leiden, 1823).[22]

Cited by Edgar Allan PoeEdgar Allan Poe's short story "Berenice" starts with a motto, the first half of a poem, by Ibn Zaiat: Dicebant mihi sodales si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. It was taken from the works of William Jones, and here is the missing part (from Complete Works, Vol. 2, London, 1799):

Dixi autem, an ideo aliud praeter hoc pectus habet sepulchrum?

My companions said to me, if I would visit the grave of my friend, I might somewhat alleviate my worries. I answered "could she be buried elsewhere than in my heart?"

BibliographyListing in most cases only editions and reprints that came out during Jones's own lifetime, books by, or prominently including work by, William Jones, are:

• Muhammad Mahdī, Histoire de Nader Chah: connu sous le nom de Thahmas Kuli Khan, empereur de Perse / Traduite d'un manuscrit persan, par ordre de Sa majesté le roi de Dannemark. Avec des notes chronologiques, historiques, géographiques. Et un traité sur la poésie orientale, par Mr. Jones, 2 vols (London: Elmsly, 1770), later published in English as The history of the life of Nader Shah: King of Persia. Extracted from an Eastern manuscript, ... With an introduction, containing, I. A description of Asia ... II. A short history of Persia ... and an appendix, consisting of an essay on Asiatick poetry, and the history of the Persian language. To which are added, pieces relative to the French translation / by William Jones (London: T. Cadell, 1773)

• William Jones, Kitāb-i Shakaristān dar naḥvī-i zabān-i Pārsī, taṣnīf-i Yūnus Ūksfurdī = A grammar of the Persian language (London: W. and J. Richardson, 1771) [2nd edn. 1775; 4th edn. London: J. Murray, S. Highley, and J. Sewell, 1797]

• [anonymously], Poems consisting chiefly of translations from the Asiatick languages: To which are added two essays, I. On the poetry of the Eastern nations. II. On the arts, commonly called imitative (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1772) [2nd edn. London: N. Conant, 1777]

• [William Jones], Poeseos Asiaticæ commentariorum libri sex: cum appendice; subjicitur Limon, seu miscellaneorum liber / auctore Gulielmo Jones (London: T. Cadell, 1774) [repr. Lipsiae: Apud Haeredes Weidmanni et Reichium, 1777]

• [anonymously], An inquiry into the legal mode of suppressing riots: with a constitutional plan of future defence (London: C. Dilly, 1780) [2nd edn, no longer anonymously, London: C. Dilly, 1782]

• William Jones, An essay on the law of bailments (London: Charles Dilly, 1781) [repr. Dublin: Henry Watts, 1790]

• William Jones, The muse recalled, an ode: occasioned by the nuptials of Lord Viscount Althorp and Miss Lavinia Bingham (Strawberry-Hill: Thomas Kirgate, 1781) [repr. Paris: F. A. Didot l'aîné, 1782]

• [anonymously], An ode, in imitation of Callistratus: sung by Mr. Webb, at the Shakespeare Tavern, on Tuesday the 14th day of May, 1782, at the anniversary dinner of the Society for Constitutional Information ([London, 1782])

• William Jones, A speech of William Jones, Esq: to the assembled inhabitants of the counties of Middlesex and Surry, the cities of London and Westminster, and the borough of Southwark. XXVIII May, M. DCC. LXXXII (London: C. Dilly, 1782)

• William Jones, The Moallakát: or seven Arabian poems, which were suspended on the temple at Mecca; with a translation, and arguments (London: P. Elmsly, 1783),

https://books.google.com/books?id=qbBCAAAAcAAJ• [anonymously], The principles of government: in a dialogue between a scholar and a peasant / written by a member of the Society for Constitutional Information ([London: The Society for Constitutional Information, 1783])

• William Jones, A discourse on the institution of a society for enquiring into the history, civil and natural, the antiquities, arts, sciences, and literature of Asia (London: T. Payne and son, 1784)

• William Davies Shipley, The whole of the proceedings at the assizes at Shrewsbury, Aug. 6, 1784: in the cause of the King on Friday August the sixth, 1784, in the cause of the King on the prosecution of William Jones, attorney-at-law, against the Rev. William Davies Shipley, Dean of St. Asaph, for a libel ... / taken in short hand by William Blanchard (London: The Society for Constitutional Information, 1784)

• William Davies Shipley, The whole proceedings on the trial of the indictment: the King, on the prosecution of William Jones, gentleman, against the Rev. William Davies Shipley, Dean of St. Asaph, for a libel, at the assize at Shrewsbury, on Friday the 6th of August, 1784, before the Hon. Francis Buller ... / taken in short-hand by Joseph Gurney (London: M. Gurney, [1784])

• Jones, William (1786). "A dissertation on the orthography of Asiatick words in Roman letters". Asiatick Researches. 1: 1–56.

• Works by William Jones at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• [William Jones (ed.)], Lailí Majnún / a Persian poem of Hátifí (Calcutta: M. Cantopher, 1788)

• [William Jones (trans.), Sacontalá: or, The fatal ring: an Indian drama / by Cálidás ; translated from the original Sanscrit and Prácrit (London: Edwards, 1790) [repr. Edinburgh: J. Mundell & Co., 1796]

• W. Jones [et al.], Dissertations and miscellaneous pieces relating to the history and antiquities, the arts, sciences, and literature, of Asia, 4 vols (London: G. Nicol, J. Walter, and J. Sewell, 1792) [repr. Dublin: P. Byrne and W. Jones, 1793]

• William Jones, Institutes of Hindu law: or, the ordinances of Menu, according to the gloss of Cullúca. Comprising the Indian system of duties, religious and civil / verbally translated from the original Sanscrit. With a preface, by Sir William Jones (Calcutta: by order of the government, 1796) [repr. London: J. Sewell and J. Debrett, 1796] [trans. by Johann Christian Hüttner, Hindu Gesetzbuch: oder, Menu's Verordnungen nach Cullucas Erläuterung. Ein Inbegriff des indischen Systems religiöser und bürgerlicher Pflichten. / Aus der Sanscrit Sprache wörtlich ins Englische übersetzt von Sir W. Jones, und verteutschet (Weimar, 1797)

• [William Jones], The works of Sir William Jones: In six volumes, ed. by A[nna] M[arie] J[ones], 6 vols (London: G. G. and J. Robinson, and R. H. Evans, 1799) [with two supplemental volumes published 1801], [repr. The works of Sir William Jones / with the life of the author by Lord Teignmouth, 13 vols (London: J. Stockdale and J. Walker, 1807)], vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4, vol. 5, vol. 6, supplemental vol. 1, supplemental vol. 2

See also• Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux

• James Prinsep

• Alexander Cunningham

• Anquetil duperron

Notes1. Curley, Thomas M. (1998). Sir Robert Chambers: Law, Literature, & Empire in the Age of Johnson. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 353. ISBN 0299151506. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

2. Curley 1998, p. 434.

3. Anthony 2010, p. 6.

4. Said 1978, p. 77.

5. Edgerton 2002, p. 10.

6. Davis & Aris 1982, p. 31.

7. "Dictionary of Indian Biography". Retrieved 10 March 2019.

8. The South Park Street Cemetery, Calcutta, published by the Association for the Preservation of Historical Cemeteries in India, 5th ed., 2009

9. Patil, Narendranath B. (2003). The Variegated Plumage: Encounters with Indian Philosophy : a Commemoration Volume in Honour of Pandit Jankinath Kaul "Kamal". Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 249.

10. Auroux, Sylvain (2000). History of the Language Sciences. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 1156. ISBN 3-11-016735-2.

11. Roger Blench Archaeology and Language: methods and issues. In: A Companion To Archaeology. J. Bintliff ed. 52–74. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2004.

12. Wheeler, Kip. "The Sanskrit Connection: Keeping Up With the Joneses". Dr.Wheeler's Website. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

13. See:

Anquetil Duperron (1808) "Supplément au Mémoire qui prècéde" (Supplement to the preceding memoir), Mémoires de littérature, tirés des registres de l'Académie royale des inscriptions et belles-lettres (Memoirs on literature, drawn from the records of the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belle-lettres), 49 : 647-697.

John J. Godfrey (1967) "Sir William Jones and Père Coeurdoux: A philological footnote," Journal of the American Oriental Society, 87 (1) : 57-59.

14. Campbell & Poser 2008, p. 37.

15. Jones, Sir William (1824). Discourses delivered before the Asiatic Society: and miscellaneous papers, on the religion, poetry, literature, etc., of the nations of India. Printed for C. S. Arnold. p. 28.

16. Damen, Mark (2012). "SECTION 7: The Indo-Europeans and Historical Linguistics". Retrieved 16 April 2013.

17. Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter (ed.). The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0. Retrieved 2 December2011.

18. Singh 2004, p. 9.

19. Quoted in M H Abrams, ‘’The Mirror and the Lamp’’ (Oxford 1971) p. 88

20. M Franklin, ‘’Orientalist Jones’’ (2011) p. 86

21. "The First European Translation of the Holy Avesta".

http://www.zoroastrian.org.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

22. P.J. Blok, P.C. Molhuysen, p. 534, Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. D.3 (1914).

References• Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

• Edgerton, Franklin (2002) [1936]. "Sir William Jones, 1746-1794". In Sebeok, Thomas A. (ed.). Portrait of Linguists. Volume 1. Thoemmes Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-441-15874-1.

• Cannon, Garland H. (1964). Oriental Jones: A biography of Sir William Jones, 1746–1794. Bombay: Asia Pub. House Indian Council for Cultural Relations.

• Cannon, Garland H. (1979). Sir William Jones: A bibliography of primary and secondary sources. Amsterdam: Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-0998-7.

• Cannon, Garland H.; & Brine, Kevin. (1995). Objects of enquiry: Life, contributions and influence of Sir William Jones. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1517-6.

• Franklin, Michael J. (1995). Sir William Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 0-7083-1295-0.

• Jones, William, Sir. (1970). The letters of Sir William Jones. Cannon, Garland H. (Ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-812404-X.

• Mukherjee, S. N. (1968). Sir William Jones: A study in eighteenth-century British attitudes to India. London, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05777-9.

• Poser, William J. and Lyle Campbell (1992). Indo-european practice and historical methodology, Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, pp. 214–236.

• Campbell, Lyle; Poser, William (2008). Language Classification: History and Method. Cambridge University Press. p. 536. ISBN 052188005X.

• Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Jones, Sir William" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 501.

• "Sir William Jones (1746 - 1794): As a Philologist, a Persian Scholar and Founder of Asiatic Society" by R M Chopra, INDO-IRANICA, Vol.66, (1 to 4), 2013.

• Singh, Upinder (2004). The discovery of ancient India: early archaeologists and the beginnings of archaeology. Permanent Black. ISBN 9788178240886.

• Said, Edward W. (1978). Orientalism. Random House. ISBN 9780804153867.

• Anthony, David W. (2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400831105.

• Davis, Samuel; Aris, Michael (1982). Views of Medieval Bhutan: the diary and drawings of Samuel Davis, 1783. Serindia.

External links• Works by or about William Jones at Internet Archive

• Urs App: William Jones's Ancient Theology. Sino-Platonic Papers Nr. 191 (September 2009) (PDF 3.7 Mb PDF, 125 p.; includes third, sixth, and ninth anniversary discourses)

• The Third Anniversary Discourse, On The Hindus

• Caissa or The Game at Chess; a Poem.

• The principles of government; in a dialogue between a scholar and a peasant. (London?; 1783)