Re: Freda Bedi, by Wikipedia

Order of the Thistle

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/12/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

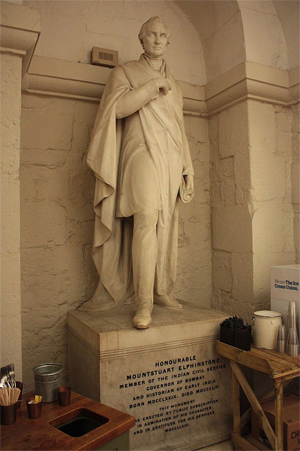

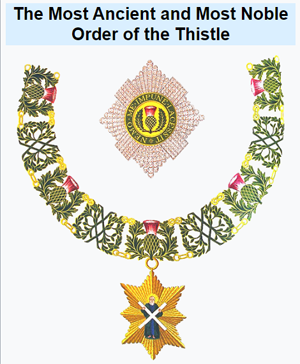

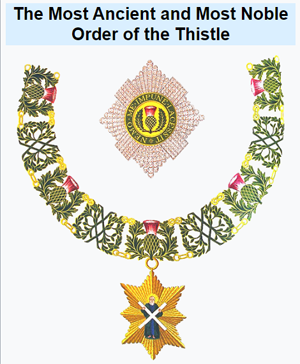

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

Insignia of a Knight Companion of The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

Awarded by the monarch of Scotland and successor states

Type Order of chivalry

Established 1687

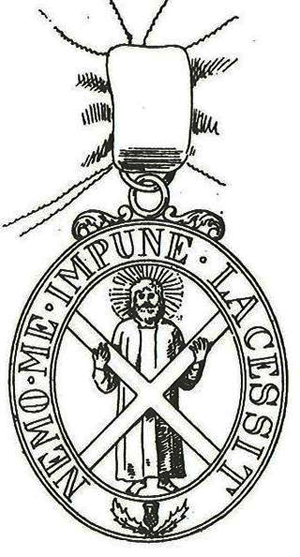

Motto Nemo me impune lacessit

Criteria At the monarch's pleasure

Status Currently constituted

Founder James VII of Scotland

Sovereign Elizabeth II

Chancellor David, Earl of Airlie

Grades

Knight/Lady Companion

KT/LT

Extra Knight/Lady

KT/LT

Statistics

First induction 29 May 1687

Last induction 9 June 2018

Total inductees

James VII: 8

Anne: 12

George I: 8

George II: 17

George III: 29

George IV: 10

William IV: 4

Victoria: 53

Edward VII: 8

George V: 27

George VI: 12

Elizabeth II: 56

Precedence

Next (higher) Order of the Garter

Next (lower) Order of St Patrick

Order of the Thistle UK ribbon.png

Riband of the Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland (James II of England and Ireland) who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order. The Order consists of the Sovereign and sixteen Knights and Ladies, as well as certain "extra" knights (members of the British Royal Family and foreign monarchs). The Sovereign alone grants membership of the Order; he or she is not advised by the Government, as occurs with most other Orders.

The Order's primary emblem is the thistle, the national flower of Scotland. The motto is Nemo me impune lacessit (Latin for "No one provokes me with impunity").[1] The same motto appears on the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom for use in Scotland and some pound coins, and is also the motto of the Royal Regiment of Scotland, Scots Guards, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada and Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. The patron saint of the Order is St Andrew.

Most British orders of chivalry cover the whole United Kingdom, but the three most exalted ones each pertain to one constituent country only. The Order of the Thistle, which pertains to Scotland, is the second-most senior in precedence. Its equivalent in England, The Most Noble Order of the Garter, is the oldest documented order of chivalry in the United Kingdom, dating to the middle fourteenth century. In 1783 an Irish equivalent, The Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick, was founded, but has now fallen dormant.

History

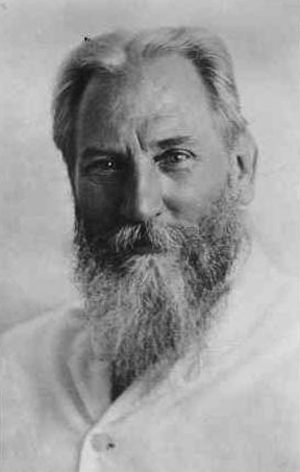

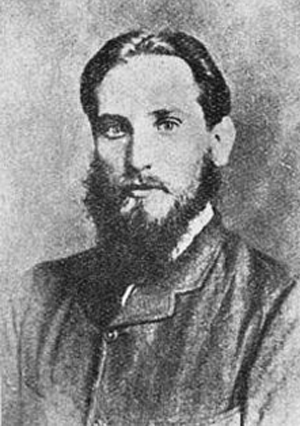

John Drummond, 1st Earl of Melfort in 1688; originator of the 'revived' Order

The claim that James VII was reviving an earlier Order is generally not supported by the evidence. The 1687 warrant states that during the 786 battle of Athelstaneford with Æthelstan of East Anglia, the cross of St Andrew appeared in the sky to Achaius, King of Scots; after his victory, he established the Order of the Thistle and dedicated it to the saint.[2] This seems unlikely, since Achaius died a century before Aethelstan.[3]

An alternative version is that the Order was founded in 809 to commemorate an alliance between Achaius and Emperor Charlemagne; there is some substance to this, as Charlemagne employed Scottish bodyguards.[4] Yet another is Robert the Bruce instituted the order after his victory at Bannockburn in 1314.[5]

Most historians consider the earliest credible claim to be the founding of the Order by James III, during the fifteenth century.[6] He adopted the thistle as the royal badge, issued coins depicting thistles and allegedly conferred membership of the "Order of the Burr or Thissil" on Francis I of France.[7][8] However, there is no conclusive evidence for this; in 1558, a French commentator described the use of the crowned thistle and St Andrew's cross on Scottish coins and banners but noted there was no Scottish order of knighthood.[9]

Writing around 1578, John Lesley refers to the three foreign orders of chivalry carved on the gate of Linlithgow Palace, with James V's ornaments of St Andrew, proper to this nation.[10] Some Scottish order of chivalry may have existed during the sixteenth century, possibly founded by James V and called the Order of St. Andrew, but lapsed by the end of that century.[11][12]

In 1610 William Fowler, the Scottish secretary to Anne of Denmark was asked about the Order of the Thistle. Fowler believed that there had been an Order, founded to honour Scots who fought for Charles VII of France. He thought it had been discontinued in the time of James V, and could say nothing of its ceremonies or regalia.[13]

James VII issued letters patent "reviving and restoring the Order of the Thistle to its full glory, lustre and magnificency" on 29 May 1687.[14][15] His intention was to reward Scottish Catholics for their loyalty but the initiative actually came from John, 1st Earl and 1st Jacobite Duke of Melfort, then Secretary of State for Scotland. Only eight members out of a possible twelve were appointed; these included Catholics, such as Melfort and the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, his elder brother James, 4th Earl and 1st Jacobite Duke of Perth, plus Protestant supporters like the Earl of Arran.[16]

After James was deposed by the 1688 Glorious Revolution and no further appointments were made until his younger daughter Anne did so in 1703.[17] It remains in existence and is used to recognise Scots 'who have held public office or contributed significantly to national life.'[18]

Founder knights; 1687 Creation

• James, Earl of Perth; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1716;

• George, Duke of Gordon; exiled in 1689 but returned home and pardoned, included in the 1703 revival by Anne, died 1716;

• John, Marquis of Atholl; reconciled with new regime in 1689, died 1703,

• James, Earl of Arran; confirmed in his titles by William III in 1698, heavily involved in the disastrous Darien Scheme, abstained from the vote passing the 1707 Acts of Union, killed in a famous duel with Lord Mohun, 1712;

• Kenneth, Earl of Seaforth; imprisoned after 1688, released in 1696 and moved to Paris, died 1701;

• John, Earl of Melfort; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1714;

• George, Earl of Dumbarton; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1692;

• Alexander, Earl of Moray; lost office after 1688, died at home 1701;

Composition

Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex in the robes of a Knight of the Order of the Thistle

The Kings of Scots, later the Kings of Great Britain and of the United Kingdom, have served as Sovereigns of the Order.[14][19] When James VII revived the Order, the statutes stated that the Order would continue the ancient number of Knights, which was described in the preceding warrant as "the Sovereign and twelve Knights-Brethren in allusion to the Blessed Saviour and his Twelve Apostles".[14][20] In 1827, George IV augmented the Order to sixteen members.[21] Women (other than Queens regnant) were originally excluded from the Order;[22] George VI created his wife Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon a Lady of the Thistle in 1937 via a special statute,[23] and in 1987 Elizabeth II allowed the regular admission of women to both the Order of the Thistle and the Order of the Garter.[6]

From time to time, individuals may be admitted to the Order by special statutes. Such members are known as "Extra Knights" and do not count towards the sixteen-member limit.[24] Members of the British Royal Family are normally admitted through this procedure; the first to be so admitted was Prince Albert.[25] King Olav V of Norway, the first foreigner to be admitted to the Order, was also admitted by special statute in 1962.[26]

The Sovereign has historically had the power to choose Knights of the Order. From the eighteenth century onwards, the Sovereign made his or her choices upon the advice of the Government. George VI felt that the Orders of the Garter and the Thistle had been used only for political patronage, rather than to reward actual merit. Therefore, with the agreement of the Prime Minister (Clement Attlee) and the Leader of the Opposition (Winston Churchill) in 1946, both Orders returned to the personal gift of the Sovereign.[27]

Vestments of a Knight of the Thistle

Knights and Ladies of the Thistle may also be admitted to the Order of the Garter. Formerly, many, but not all, Knights elevated to the senior Order would resign from the Order of the Thistle.[28] The first to resign from the Order of the Thistle was John, Duke of Argyll in 1710;[29] the last to take such an action was Thomas, Earl of Zetland in 1872.[30] Knights and Ladies of the Thistle may also be deprived of their knighthoods. The only individual to have suffered such a fate was John Erskine, 6th Earl of Mar who lost both the knighthood and the earldom after participating in the Jacobite rising of 1715.[31]

The Order has five officers: the Dean, the Chancellor, the Usher, the Lord Lyon King of Arms and the Secretary. The Dean is normally a cleric of the Church of Scotland. This office was not part of the original establishment, but was created in 1763 and joined to the office of Dean of the Chapel Royal.[32] The two offices were separated in 1969.[33] The office of Chancellor is mentioned and given custody of the seal of the Order in the 1687 statutes, but no-one was appointed to the position until 1913.[34] The office has subsequently been held by one of the knights, though not necessarily the most senior. The Usher of the Order is the Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod (unlike his Garter equivalent, the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, he does not have another function assisting the House of Lords).[35] The Lord Lyon King of Arms, head of the Scottish heraldic establishment and whose office predates his association with the Order serves as King of Arms of the Order.[36] The Lord Lyon often—but not invariably—also serves as the Secretary.

Habit and insignia

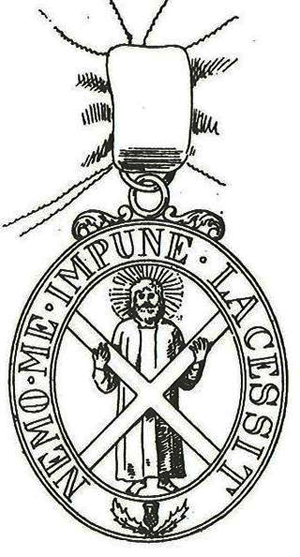

The St Andrew with the saltire in the badge of the Order of the Thistle

The star of the Order of the Thistle

For the Order's great occasions, such as its annual service each June or July, as well for coronations, the Knights and Ladies wear an elaborate costume:[37]

• The mantle is a green robe worn over their suits or military uniforms. The mantle is lined with white taffeta; it is tied with green and gold tassels. On the left shoulder of the mantle, the star of the Order (see below) is depicted.[38]

• The hat is made of black velvet and is plumed with white feathers with a black egret or heron's top in the middle.[38]

• The collar is made of gold and depicts thistles and sprigs of rue. It is worn over the mantle.[38]

• The St Andrew, also called the badge-appendant, is worn suspended from the collar. It comprises a gold enamelled depiction of St Andrew, wearing a green gown and purple coat, holding a white saltire.[38] Gold rays of a glory are shown emanating from St Andrew's head.[39]

Aside from these special occasions, however, much simpler insignia are used whenever a member of the Order attends an event at which decorations are worn.

• The star of the Order consists of a silver St Andrew's saltire, with clusters of rays between the arms thereof. In the centre is depicted a green circle bearing the motto of the Order in gold majuscules; within the circle, there is depicted a thistle on a gold field. It is worn pinned to the left breast.[40] (Since the Order of the Thistle is the second-most senior chivalric order in the UK, a member will wear its star above that of other orders to which he or she belongs, except that of the Order of the Garter; up to four orders' stars may be worn.)[41]

• The broad riband is a dark green sash worn across the body, from the left shoulder to the right hip.[42]

• At the right hip of the Riband, the badge of the Order is attached. The badge depicts St Andrew in the same form as the badge-appendant surrounded by the Order's motto.[43]

However, on certain collar days designated by the Sovereign,[44] members attending formal events may wear the Order's collar over their military uniform, formal wear, or other costume. They will then substitute the broad riband of another order to which they belong (if any), since the Order of the Thistle is represented by the collar.[45]

Upon the death of a Knight or Lady, the insignia must be returned to the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood. The badge and star are returned personally to the Sovereign by the nearest relative of the deceased.[46]

Officers of the Order also wear green robes.[47] The Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod also bears, as the title of his office suggests, a green rod.[48]

One unusual recipient of the Order of the Thistle was James, Earl of Southesk (1827-1905). He was recognized by the Order for his adventurous spirit and his passion for the wilds of Canada. His portrait in marble by William Grant Stevenson depicts a stern man who had placed himself at some risk as he travelled through the Canadian wilderness and wrote about his admiration for the native peoples of North America.

Chapel

Swords, helms and crests of Knights of the Thistle above their stalls in the Thistle Chapel. Lady Marion Fraser's helm and crest are second from the left

Stall plates of Knights of the Thistle

When James VII created the modern Order in 1687, he directed that the Abbey Church at the Palace of Holyroodhouse be converted to a Chapel for the Order of the Thistle, perhaps copying the idea from the Order of the Garter (whose chapel is located in Windsor Castle). James VII, however, was deposed by 1688; the Chapel, meanwhile, had been destroyed during riots. The Order did not have a Chapel until 1911, when one was added onto St Giles High Kirk in Edinburgh.[49] Each year, the Sovereign resides at the Palace of Holyroodhouse for a week in June or July; during the visit, a service for the Order is held. Any new Knights or Ladies are installed at annual services.[6]

Each member of the Order, including the Sovereign, is allotted a stall in the Chapel, above which his or her heraldic devices are displayed. Perched on the pinnacle of a knight's stall is his helm, decorated with mantling and topped by his crest. If he is a peer, the coronet appropriate to his rank is placed beneath the helm.[50] Under the laws of heraldry, women, other than monarchs, do not normally bear helms nor crests;[51] instead, the coronet alone is used (if she is a peeress or princess).[52] Lady Marion Fraser had a helm and crest included when she was granted arms; these are displayed above her stall in the same manner as for knights.[53] Unlike other British Orders, the armorial banners of Knights and Ladies of the Thistle are not hung in the chapel, but instead in an adjacent part of St Giles High Kirk.[54] The Thistle Chapel does, however, bear the arms of members living and deceased on stall plates. These enamelled plates are affixed to the back of the stall and display its occupant's name, arms, and date of admission into the Order.[55]

Upon the death of a Knight, helm, mantling, crest (or coronet or crown) and sword are taken down. The stall plates, however, are not removed; rather, they remain permanently affixed to the back of the stall, so that the stalls of the chapel are festooned with a colourful record of the Order's Knights (and now Ladies) since 1911.[56] The entryway just outside the doors of the chapel has the names of the Order's Knights from before 1911 inscribed into the walls giving a complete record of the members of the order.

Precedence and privileges

Banners of Knights of the Thistle, hanging in St Giles High Kirk

Knights and Ladies of the Thistle are assigned positions in the order of precedence, ranking above all others of knightly rank except the Order of the Garter, and above baronets. Wives, sons, daughters and daughters-in-law of Knights of the Thistle also feature on the order of precedence; relatives of Ladies of the Thistle, however, are not assigned any special precedence. (Generally, individuals can derive precedence from their fathers or husbands, but not from their mothers or wives.)[57]

Knights of the Thistle prefix "Sir", and Ladies prefix "Lady", to their forenames. Wives of Knights may prefix "Lady" to their surnames, but no equivalent privilege exists for husbands of Ladies. Such forms are not used by peers and princes, except when the names of the former are written out in their fullest forms.[58]

Knights and Ladies use the post-nominal letters "KT" and "LT" respectively.[6] When an individual is entitled to use multiple post-nominal letters, "KT" or "LT" appears before all others, except "Bt" or "Btss" (Baronet or Baronetess), "VC" (Victoria Cross), "GC" (George Cross) and "KG" or "LG" (Knight or Lady of the Garter).[41]

Knights and Ladies may encircle their arms with the circlet (a green circle bearing the Order's motto) and the collar of the Order; the former is shown either outside or on top of the latter. The badge is depicted suspended from the collar.[59] The Royal Arms depict the collar and motto of the Order of the Thistle only in Scotland; they show the circlet and motto of the Garter in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[60]

Knights and Ladies are also entitled to receive heraldic supporters. This high privilege is shared only by members of the Royal Family, peers, Knights and Ladies of the Garter, and Knights and Dames Grand Cross of the junior orders of chivalry and clan chiefs.[61]

Current members and officers

• Sovereign: Elizabeth II

• Knights and Ladies Companion:

1. The Earl of Elgin and Kincardine KT JP DL (1981)

2. The Earl of Airlie KT GCVO PC JP (1985)

3. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres KT GCVO PC DL (1996)

4. The Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden KT DL (1996)

5. The Lord Mackay of Clashfern KT PC QC (1997)

6. The Lord Wilson of Tillyorn KT GCMG (2000)

7. Sir Eric Anderson KT (2002)

8. The Lord Steel of Aikwood KT KBE PC (2004)

9. The Lord Robertson of Port Ellen KT GCMG PC (2004)

10. The Lord Cullen of Whitekirk KT PC QC (2007)

11. The Lord Hope of Craighead KT PC QC (2009)

12. The Lord Patel KT (2009)

13. The Earl of Home KT CVO CBE (2014)

14. The Lord Smith of Kelvin KT CH (2014)

15. The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KT KBE DL FSA FRSE (2017)

16. Sir Ian Wood KT GBE (2018)

• Extra Knights and Ladies Companion:

1. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh KG KT OM GCVO GBE AK CC CMM QSO PC ADC(P) CD (1952)

2. Prince Charles, Duke of Rothesay KG KT GCB OM AK CC QSO PC ADC(P) CD (1977)

3. Anne, Princess Royal KG KT GCVO QSO CD (2000)

4. Prince William, Earl of Strathearn KG KT PC ADC(P) (2012)

• Officers:

o Chancellor: The Earl of Airlie KT GCVO PC JP

o Dean: The Reverend Professor David Fergusson, OBE FBA FRSE

o Secretary of the Thistle: Elizabeth Roads LVO

o Lyon King of Arms: Joseph Morrow, CBE QC DL (Lord Lyon King of Arms)

o Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod: Rear Admiral Christopher Hope Layman CB DSO LVO

See also

• List of Knights and Ladies of the Thistle (1687–present)

Notes

1. 1687 Statutes, quoted in Statutes (1987), p6

2. This version, without the date, is given in the warrant 'reviving' the Order in 1687. (1687 warrant, quoted in Statutes, 1978, p. 1)

3. Nicholas, p4, footnote 1, notes that Achaius died more than a century before Aethelstan

4. Nicolas, Appendix, p.vi, quotes Nisbet's A system of heraldry, which relates this version.

5. Mackey and Heywood, p. 890

6. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Thistle". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

7. Nicolas, p. 3

8. Nicolas, footnote7, p. 15, quotes Nisbet in support of these claims.

9. Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (1898), 206.

10. Leslie, John, Historie of Scotland, vol. 2, STS (1895), 230–1.

11. Stevenson, Katie "The Unicorn, St Andrew and the Thistle: Was there an Order of Chivalry in Late Medieval Scotland?", Scottish Historical Review. Volume 83, Page 3–22, April 2004

12. Nicolas quotes Elias Ashmole's Treatise on Military Orders (1672) which mentions a ceremony involving Knights of St Andrew (i.e. Knights of the Thistle) but Nicolas goes on to say that "it was not pretended that there were any "Knights of the Thistle" or "of St Andrew" after the accession of James VI in 1567"

13. E. K. Purnell & A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, vol. 2 (London, 1936), pp. xxii-xxiii, 388.

14. "No. 2251". The London Gazette. 13 June 1687. pp. 1–2.

15. 1687 Warrant, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 1

16. Glozier, Mathew (2000). "The Earl of Melfort, the Court Catholic Party and the Foundation of the Order of the Thistle, 1687". The Scottish Historical Review. 79 (208): 233–234. doi:10.3366/shr.2000.79.2.233. JSTOR 25530975.

17. Joseph Timothy Haydn's Book of Dignities (Longmans, 1851), p. 434

18. "The Order of the Thistle". The Royal Family. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

19. 1687 Warrant, quoted in Statutes (1978), p2 states revive the said Order, of which his Majesty is the undoubted and rightful Sovereign

20. 1687 Warrant and 1687 Statutes, quoted in Statutes (1987) pp. 1–3

21. Warrant of 8 May 1827, quoted in Statutes (1978)

22. Members of the Order had to be Knights Bachelor before appointment (1703 Statutes, article 14, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17); only men could be created as such.

23. Additional statute, 12 June 1937, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 60

24. Many such statutes are quoted in Statutes (1978), all of which follow a fixed formula.

25. Additional statute 17 January 1842, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 33. The first Royal Knight (other than a monarch) was a younger son of George III, The Prince William Henry (later William IV), however he was admitted as one of the twelve ordinary knights (Nicolas, p. 51).

26. Additional statute of 18 October 1962, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 63

27. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Garter". The Royal Household. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

28. Nicolas, p. 33, says that the Duke of Hamilton was given special permission by Queen Anne, hitherto unprecedented, to belong to both the Orders of the Thistle and Garter.

29. Nicolas, p. 32

30. The Times, 30 November 1872, p. 9

31. Nicolas, p. 35. Unlike the other British orders, the statutes of the Order of the Thistle do not specify a procedure for the removal of a Knight.

32. Warrant of 7 January 1763, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp28–29

33. "No. 44902". The London Gazette. 22 July 1969. p. 7525.

34. Statute of 8 October 1913, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 49

35. 1703 Statutes, article 13, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17, refer to the office only as the Usher, and does not specify the colour of his baton of office, however by the time of a statute of 17 July 1717 he is referred to as Green Rod.

36. 1703 Statutes, article 11, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17 does not assign any duties to Lord Lyon, but merely prescribes his vestments and insignia.

37. For an early illustration, see: Hélyot, P. (1719) 'Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires, et des congregations séculières de l'un et de l'autre sexe, qui ont été établis jusqu'à présent' Paris, Vol. VIII, p. 389.

38. 1703 Statutes, article 2, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16

39. Statute of 17 February 1714/15, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 20

40. 1703 Statutes, article 5, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16

41. "Order of Wear". Ceremonial Secretariat, Cabinet Office. 13 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

42. 1703 Statutes, article 3, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 15. In the 1687 statutes the riband was purple-blue; the colour was changed by Queen Anne when she refounded the Order.

43. 1703 Statutes, article 3, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 15 refers to this item of insignia as the medal.

44. 1703 Statutes, article 7, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 16

45. "Royal Insight: Mailbox". The Royal Household. February 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

46. Debrett's Peerage, p. 82

47. 1703 Statutes, article 11 (Secretary), article 12 (Lord Lyon), article 13 (Usher); Special statute of 10 July 1886 (Dean), Statute of 8 October 1913 (Chancellor), all quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16, 42 and 49–50

48. 1703 Statutes, article 13, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16, says only that he carries his "baton of office"

49. Burnett and Hodgson, pp6–7. The 1703 statutes however continue to designate this as the chapel of the Order

50. Paul, pp32–33

51. Innes, p35

52. Cox, N. (1999). "The Coronets of Members of the Royal Family and of the Peerage (The Double Tressure)". Journal of the Heraldry Society of Scotland (22): 8–13. Archived from the original on 21 November 2001.

53. Burnett and Hodgson, p208

54. Innes, p42

55. Burnett and Hodgson, pp. 7–8, and illustrations on pp. 54 ff. Only stall plates for Knights and Ladies appointed after 1911 give the name and date of appointment.

56. Burnett and Hodgson

57. "The Scale of General Precedence in Scotland". Burke's Peerage. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

58. The Crown Office (July 2003). "Forms of Address for use orally and in correspondence". Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 6 March 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

59. Innes, p. 47. The circlet does not appear to be commonly used. Neither the collar nor the circlet are used on the stall plates; Burnett and Hodgson on the occasions when the insignia of the Order are mentioned in a grant or matriculation of arms in Burnett and Hodgson (e.g. pp. 134, 138, 174, 180, 198) it is only the collar which is used.

60. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Symbols: Coats of Arms". The Royal Household. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

61. Woodcock and Robinson, p. 93

References

Printed

• Burnett, C.J.; Hodgson, L. (2001). Stall Plates of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle in the Chapel of the Order within St Giles' Cathedral, The High Kirk of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Heraldry Society of Scotland. ISBN 978-0-9525258-3-7.

• Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage. London: Debrett's Peerage Ltd. 1995.

• Galloway, Peter (2009). The Order of the Thistle. Spink & Son Ltd. ISBN 978-1-902040-92-9.

• Innes of Learney, T. (1956). Scots heraldry; a practical handbook on the historical principles and modern application of the art and science (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

• Mackey, A.G.; Haywood, H.L. (1946). Encyclopedia of Freemasonry. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-4719-5.

• Nicolas, N. H. (1842). History of the orders of knighthood of the British empire, of the order of the Guelphs of Hanover; and of the medals, clasps, and crosses, conferred for naval and military service, Vol iii. London.

• Paul, J.B. (1911). The knights of the Order of the Thistle: a historical sketch by the Lord Lyon King of Arms, and a descriptive sketch of their chapel by J. Warrack. Edinburgh.

• Order of the Thistle (1978). Statutes of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle: revived by His Majesty King James II of England and VII of Scotland and again revived by Her Majesty Queen Anne. Edinburgh.

• Woodcock, T.; Robinson, J.M. (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211658-1.

Online

• "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Thistle". The official website of the British Monarchy. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

• "Royal Insight: Mailbox". The Royal Household. February 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

• "The Scale of General Precedence in Scotland". Burke's Peerage. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/12/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

Insignia of a Knight Companion of The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

Awarded by the monarch of Scotland and successor states

Type Order of chivalry

Established 1687

Motto Nemo me impune lacessit

Criteria At the monarch's pleasure

Status Currently constituted

Founder James VII of Scotland

Sovereign Elizabeth II

Chancellor David, Earl of Airlie

Grades

Knight/Lady Companion

KT/LT

Extra Knight/Lady

KT/LT

Statistics

First induction 29 May 1687

Last induction 9 June 2018

Total inductees

James VII: 8

Anne: 12

George I: 8

George II: 17

George III: 29

George IV: 10

William IV: 4

Victoria: 53

Edward VII: 8

George V: 27

George VI: 12

Elizabeth II: 56

Precedence

Next (higher) Order of the Garter

Next (lower) Order of St Patrick

Order of the Thistle UK ribbon.png

Riband of the Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland (James II of England and Ireland) who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order. The Order consists of the Sovereign and sixteen Knights and Ladies, as well as certain "extra" knights (members of the British Royal Family and foreign monarchs). The Sovereign alone grants membership of the Order; he or she is not advised by the Government, as occurs with most other Orders.

The Order's primary emblem is the thistle, the national flower of Scotland. The motto is Nemo me impune lacessit (Latin for "No one provokes me with impunity").[1] The same motto appears on the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom for use in Scotland and some pound coins, and is also the motto of the Royal Regiment of Scotland, Scots Guards, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada and Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. The patron saint of the Order is St Andrew.

Most British orders of chivalry cover the whole United Kingdom, but the three most exalted ones each pertain to one constituent country only. The Order of the Thistle, which pertains to Scotland, is the second-most senior in precedence. Its equivalent in England, The Most Noble Order of the Garter, is the oldest documented order of chivalry in the United Kingdom, dating to the middle fourteenth century. In 1783 an Irish equivalent, The Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick, was founded, but has now fallen dormant.

History

John Drummond, 1st Earl of Melfort in 1688; originator of the 'revived' Order

The claim that James VII was reviving an earlier Order is generally not supported by the evidence. The 1687 warrant states that during the 786 battle of Athelstaneford with Æthelstan of East Anglia, the cross of St Andrew appeared in the sky to Achaius, King of Scots; after his victory, he established the Order of the Thistle and dedicated it to the saint.[2] This seems unlikely, since Achaius died a century before Aethelstan.[3]

An alternative version is that the Order was founded in 809 to commemorate an alliance between Achaius and Emperor Charlemagne; there is some substance to this, as Charlemagne employed Scottish bodyguards.[4] Yet another is Robert the Bruce instituted the order after his victory at Bannockburn in 1314.[5]

Most historians consider the earliest credible claim to be the founding of the Order by James III, during the fifteenth century.[6] He adopted the thistle as the royal badge, issued coins depicting thistles and allegedly conferred membership of the "Order of the Burr or Thissil" on Francis I of France.[7][8] However, there is no conclusive evidence for this; in 1558, a French commentator described the use of the crowned thistle and St Andrew's cross on Scottish coins and banners but noted there was no Scottish order of knighthood.[9]

Writing around 1578, John Lesley refers to the three foreign orders of chivalry carved on the gate of Linlithgow Palace, with James V's ornaments of St Andrew, proper to this nation.[10] Some Scottish order of chivalry may have existed during the sixteenth century, possibly founded by James V and called the Order of St. Andrew, but lapsed by the end of that century.[11][12]

In 1610 William Fowler, the Scottish secretary to Anne of Denmark was asked about the Order of the Thistle. Fowler believed that there had been an Order, founded to honour Scots who fought for Charles VII of France. He thought it had been discontinued in the time of James V, and could say nothing of its ceremonies or regalia.[13]

James VII issued letters patent "reviving and restoring the Order of the Thistle to its full glory, lustre and magnificency" on 29 May 1687.[14][15] His intention was to reward Scottish Catholics for their loyalty but the initiative actually came from John, 1st Earl and 1st Jacobite Duke of Melfort, then Secretary of State for Scotland. Only eight members out of a possible twelve were appointed; these included Catholics, such as Melfort and the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, his elder brother James, 4th Earl and 1st Jacobite Duke of Perth, plus Protestant supporters like the Earl of Arran.[16]

After James was deposed by the 1688 Glorious Revolution and no further appointments were made until his younger daughter Anne did so in 1703.[17] It remains in existence and is used to recognise Scots 'who have held public office or contributed significantly to national life.'[18]

Founder knights; 1687 Creation

• James, Earl of Perth; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1716;

• George, Duke of Gordon; exiled in 1689 but returned home and pardoned, included in the 1703 revival by Anne, died 1716;

• John, Marquis of Atholl; reconciled with new regime in 1689, died 1703,

• James, Earl of Arran; confirmed in his titles by William III in 1698, heavily involved in the disastrous Darien Scheme, abstained from the vote passing the 1707 Acts of Union, killed in a famous duel with Lord Mohun, 1712;

• Kenneth, Earl of Seaforth; imprisoned after 1688, released in 1696 and moved to Paris, died 1701;

• John, Earl of Melfort; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1714;

• George, Earl of Dumbarton; went into exile with James in 1688, died in France 1692;

• Alexander, Earl of Moray; lost office after 1688, died at home 1701;

Composition

Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex in the robes of a Knight of the Order of the Thistle

The Kings of Scots, later the Kings of Great Britain and of the United Kingdom, have served as Sovereigns of the Order.[14][19] When James VII revived the Order, the statutes stated that the Order would continue the ancient number of Knights, which was described in the preceding warrant as "the Sovereign and twelve Knights-Brethren in allusion to the Blessed Saviour and his Twelve Apostles".[14][20] In 1827, George IV augmented the Order to sixteen members.[21] Women (other than Queens regnant) were originally excluded from the Order;[22] George VI created his wife Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon a Lady of the Thistle in 1937 via a special statute,[23] and in 1987 Elizabeth II allowed the regular admission of women to both the Order of the Thistle and the Order of the Garter.[6]

From time to time, individuals may be admitted to the Order by special statutes. Such members are known as "Extra Knights" and do not count towards the sixteen-member limit.[24] Members of the British Royal Family are normally admitted through this procedure; the first to be so admitted was Prince Albert.[25] King Olav V of Norway, the first foreigner to be admitted to the Order, was also admitted by special statute in 1962.[26]

The Sovereign has historically had the power to choose Knights of the Order. From the eighteenth century onwards, the Sovereign made his or her choices upon the advice of the Government. George VI felt that the Orders of the Garter and the Thistle had been used only for political patronage, rather than to reward actual merit. Therefore, with the agreement of the Prime Minister (Clement Attlee) and the Leader of the Opposition (Winston Churchill) in 1946, both Orders returned to the personal gift of the Sovereign.[27]

Vestments of a Knight of the Thistle

Knights and Ladies of the Thistle may also be admitted to the Order of the Garter. Formerly, many, but not all, Knights elevated to the senior Order would resign from the Order of the Thistle.[28] The first to resign from the Order of the Thistle was John, Duke of Argyll in 1710;[29] the last to take such an action was Thomas, Earl of Zetland in 1872.[30] Knights and Ladies of the Thistle may also be deprived of their knighthoods. The only individual to have suffered such a fate was John Erskine, 6th Earl of Mar who lost both the knighthood and the earldom after participating in the Jacobite rising of 1715.[31]

The Order has five officers: the Dean, the Chancellor, the Usher, the Lord Lyon King of Arms and the Secretary. The Dean is normally a cleric of the Church of Scotland. This office was not part of the original establishment, but was created in 1763 and joined to the office of Dean of the Chapel Royal.[32] The two offices were separated in 1969.[33] The office of Chancellor is mentioned and given custody of the seal of the Order in the 1687 statutes, but no-one was appointed to the position until 1913.[34] The office has subsequently been held by one of the knights, though not necessarily the most senior. The Usher of the Order is the Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod (unlike his Garter equivalent, the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, he does not have another function assisting the House of Lords).[35] The Lord Lyon King of Arms, head of the Scottish heraldic establishment and whose office predates his association with the Order serves as King of Arms of the Order.[36] The Lord Lyon often—but not invariably—also serves as the Secretary.

Habit and insignia

The St Andrew with the saltire in the badge of the Order of the Thistle

The star of the Order of the Thistle

For the Order's great occasions, such as its annual service each June or July, as well for coronations, the Knights and Ladies wear an elaborate costume:[37]

• The mantle is a green robe worn over their suits or military uniforms. The mantle is lined with white taffeta; it is tied with green and gold tassels. On the left shoulder of the mantle, the star of the Order (see below) is depicted.[38]

• The hat is made of black velvet and is plumed with white feathers with a black egret or heron's top in the middle.[38]

• The collar is made of gold and depicts thistles and sprigs of rue. It is worn over the mantle.[38]

• The St Andrew, also called the badge-appendant, is worn suspended from the collar. It comprises a gold enamelled depiction of St Andrew, wearing a green gown and purple coat, holding a white saltire.[38] Gold rays of a glory are shown emanating from St Andrew's head.[39]

Aside from these special occasions, however, much simpler insignia are used whenever a member of the Order attends an event at which decorations are worn.

• The star of the Order consists of a silver St Andrew's saltire, with clusters of rays between the arms thereof. In the centre is depicted a green circle bearing the motto of the Order in gold majuscules; within the circle, there is depicted a thistle on a gold field. It is worn pinned to the left breast.[40] (Since the Order of the Thistle is the second-most senior chivalric order in the UK, a member will wear its star above that of other orders to which he or she belongs, except that of the Order of the Garter; up to four orders' stars may be worn.)[41]

• The broad riband is a dark green sash worn across the body, from the left shoulder to the right hip.[42]

• At the right hip of the Riband, the badge of the Order is attached. The badge depicts St Andrew in the same form as the badge-appendant surrounded by the Order's motto.[43]

However, on certain collar days designated by the Sovereign,[44] members attending formal events may wear the Order's collar over their military uniform, formal wear, or other costume. They will then substitute the broad riband of another order to which they belong (if any), since the Order of the Thistle is represented by the collar.[45]

Upon the death of a Knight or Lady, the insignia must be returned to the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood. The badge and star are returned personally to the Sovereign by the nearest relative of the deceased.[46]

Officers of the Order also wear green robes.[47] The Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod also bears, as the title of his office suggests, a green rod.[48]

One unusual recipient of the Order of the Thistle was James, Earl of Southesk (1827-1905). He was recognized by the Order for his adventurous spirit and his passion for the wilds of Canada. His portrait in marble by William Grant Stevenson depicts a stern man who had placed himself at some risk as he travelled through the Canadian wilderness and wrote about his admiration for the native peoples of North America.

Chapel

Swords, helms and crests of Knights of the Thistle above their stalls in the Thistle Chapel. Lady Marion Fraser's helm and crest are second from the left

Stall plates of Knights of the Thistle

When James VII created the modern Order in 1687, he directed that the Abbey Church at the Palace of Holyroodhouse be converted to a Chapel for the Order of the Thistle, perhaps copying the idea from the Order of the Garter (whose chapel is located in Windsor Castle). James VII, however, was deposed by 1688; the Chapel, meanwhile, had been destroyed during riots. The Order did not have a Chapel until 1911, when one was added onto St Giles High Kirk in Edinburgh.[49] Each year, the Sovereign resides at the Palace of Holyroodhouse for a week in June or July; during the visit, a service for the Order is held. Any new Knights or Ladies are installed at annual services.[6]

Each member of the Order, including the Sovereign, is allotted a stall in the Chapel, above which his or her heraldic devices are displayed. Perched on the pinnacle of a knight's stall is his helm, decorated with mantling and topped by his crest. If he is a peer, the coronet appropriate to his rank is placed beneath the helm.[50] Under the laws of heraldry, women, other than monarchs, do not normally bear helms nor crests;[51] instead, the coronet alone is used (if she is a peeress or princess).[52] Lady Marion Fraser had a helm and crest included when she was granted arms; these are displayed above her stall in the same manner as for knights.[53] Unlike other British Orders, the armorial banners of Knights and Ladies of the Thistle are not hung in the chapel, but instead in an adjacent part of St Giles High Kirk.[54] The Thistle Chapel does, however, bear the arms of members living and deceased on stall plates. These enamelled plates are affixed to the back of the stall and display its occupant's name, arms, and date of admission into the Order.[55]

Upon the death of a Knight, helm, mantling, crest (or coronet or crown) and sword are taken down. The stall plates, however, are not removed; rather, they remain permanently affixed to the back of the stall, so that the stalls of the chapel are festooned with a colourful record of the Order's Knights (and now Ladies) since 1911.[56] The entryway just outside the doors of the chapel has the names of the Order's Knights from before 1911 inscribed into the walls giving a complete record of the members of the order.

Precedence and privileges

Banners of Knights of the Thistle, hanging in St Giles High Kirk

Knights and Ladies of the Thistle are assigned positions in the order of precedence, ranking above all others of knightly rank except the Order of the Garter, and above baronets. Wives, sons, daughters and daughters-in-law of Knights of the Thistle also feature on the order of precedence; relatives of Ladies of the Thistle, however, are not assigned any special precedence. (Generally, individuals can derive precedence from their fathers or husbands, but not from their mothers or wives.)[57]

Knights of the Thistle prefix "Sir", and Ladies prefix "Lady", to their forenames. Wives of Knights may prefix "Lady" to their surnames, but no equivalent privilege exists for husbands of Ladies. Such forms are not used by peers and princes, except when the names of the former are written out in their fullest forms.[58]

Knights and Ladies use the post-nominal letters "KT" and "LT" respectively.[6] When an individual is entitled to use multiple post-nominal letters, "KT" or "LT" appears before all others, except "Bt" or "Btss" (Baronet or Baronetess), "VC" (Victoria Cross), "GC" (George Cross) and "KG" or "LG" (Knight or Lady of the Garter).[41]

Knights and Ladies may encircle their arms with the circlet (a green circle bearing the Order's motto) and the collar of the Order; the former is shown either outside or on top of the latter. The badge is depicted suspended from the collar.[59] The Royal Arms depict the collar and motto of the Order of the Thistle only in Scotland; they show the circlet and motto of the Garter in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[60]

Knights and Ladies are also entitled to receive heraldic supporters. This high privilege is shared only by members of the Royal Family, peers, Knights and Ladies of the Garter, and Knights and Dames Grand Cross of the junior orders of chivalry and clan chiefs.[61]

Current members and officers

• Sovereign: Elizabeth II

• Knights and Ladies Companion:

1. The Earl of Elgin and Kincardine KT JP DL (1981)

2. The Earl of Airlie KT GCVO PC JP (1985)

3. The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres KT GCVO PC DL (1996)

4. The Lord Macfarlane of Bearsden KT DL (1996)

5. The Lord Mackay of Clashfern KT PC QC (1997)

6. The Lord Wilson of Tillyorn KT GCMG (2000)

7. Sir Eric Anderson KT (2002)

8. The Lord Steel of Aikwood KT KBE PC (2004)

9. The Lord Robertson of Port Ellen KT GCMG PC (2004)

10. The Lord Cullen of Whitekirk KT PC QC (2007)

11. The Lord Hope of Craighead KT PC QC (2009)

12. The Lord Patel KT (2009)

13. The Earl of Home KT CVO CBE (2014)

14. The Lord Smith of Kelvin KT CH (2014)

15. The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KT KBE DL FSA FRSE (2017)

16. Sir Ian Wood KT GBE (2018)

• Extra Knights and Ladies Companion:

1. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh KG KT OM GCVO GBE AK CC CMM QSO PC ADC(P) CD (1952)

2. Prince Charles, Duke of Rothesay KG KT GCB OM AK CC QSO PC ADC(P) CD (1977)

3. Anne, Princess Royal KG KT GCVO QSO CD (2000)

4. Prince William, Earl of Strathearn KG KT PC ADC(P) (2012)

• Officers:

o Chancellor: The Earl of Airlie KT GCVO PC JP

o Dean: The Reverend Professor David Fergusson, OBE FBA FRSE

o Secretary of the Thistle: Elizabeth Roads LVO

o Lyon King of Arms: Joseph Morrow, CBE QC DL (Lord Lyon King of Arms)

o Gentleman Usher of the Green Rod: Rear Admiral Christopher Hope Layman CB DSO LVO

See also

• List of Knights and Ladies of the Thistle (1687–present)

Notes

1. 1687 Statutes, quoted in Statutes (1987), p6

2. This version, without the date, is given in the warrant 'reviving' the Order in 1687. (1687 warrant, quoted in Statutes, 1978, p. 1)

3. Nicholas, p4, footnote 1, notes that Achaius died more than a century before Aethelstan

4. Nicolas, Appendix, p.vi, quotes Nisbet's A system of heraldry, which relates this version.

5. Mackey and Heywood, p. 890

6. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Thistle". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

7. Nicolas, p. 3

8. Nicolas, footnote7, p. 15, quotes Nisbet in support of these claims.

9. Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 1 (1898), 206.

10. Leslie, John, Historie of Scotland, vol. 2, STS (1895), 230–1.

11. Stevenson, Katie "The Unicorn, St Andrew and the Thistle: Was there an Order of Chivalry in Late Medieval Scotland?", Scottish Historical Review. Volume 83, Page 3–22, April 2004

12. Nicolas quotes Elias Ashmole's Treatise on Military Orders (1672) which mentions a ceremony involving Knights of St Andrew (i.e. Knights of the Thistle) but Nicolas goes on to say that "it was not pretended that there were any "Knights of the Thistle" or "of St Andrew" after the accession of James VI in 1567"

13. E. K. Purnell & A. B. Hinds, HMC Downshire, vol. 2 (London, 1936), pp. xxii-xxiii, 388.

14. "No. 2251". The London Gazette. 13 June 1687. pp. 1–2.

15. 1687 Warrant, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 1

16. Glozier, Mathew (2000). "The Earl of Melfort, the Court Catholic Party and the Foundation of the Order of the Thistle, 1687". The Scottish Historical Review. 79 (208): 233–234. doi:10.3366/shr.2000.79.2.233. JSTOR 25530975.

17. Joseph Timothy Haydn's Book of Dignities (Longmans, 1851), p. 434

18. "The Order of the Thistle". The Royal Family. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

19. 1687 Warrant, quoted in Statutes (1978), p2 states revive the said Order, of which his Majesty is the undoubted and rightful Sovereign

20. 1687 Warrant and 1687 Statutes, quoted in Statutes (1987) pp. 1–3

21. Warrant of 8 May 1827, quoted in Statutes (1978)

22. Members of the Order had to be Knights Bachelor before appointment (1703 Statutes, article 14, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17); only men could be created as such.

23. Additional statute, 12 June 1937, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 60

24. Many such statutes are quoted in Statutes (1978), all of which follow a fixed formula.

25. Additional statute 17 January 1842, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 33. The first Royal Knight (other than a monarch) was a younger son of George III, The Prince William Henry (later William IV), however he was admitted as one of the twelve ordinary knights (Nicolas, p. 51).

26. Additional statute of 18 October 1962, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 63

27. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Garter". The Royal Household. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

28. Nicolas, p. 33, says that the Duke of Hamilton was given special permission by Queen Anne, hitherto unprecedented, to belong to both the Orders of the Thistle and Garter.

29. Nicolas, p. 32

30. The Times, 30 November 1872, p. 9

31. Nicolas, p. 35. Unlike the other British orders, the statutes of the Order of the Thistle do not specify a procedure for the removal of a Knight.

32. Warrant of 7 January 1763, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp28–29

33. "No. 44902". The London Gazette. 22 July 1969. p. 7525.

34. Statute of 8 October 1913, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 49

35. 1703 Statutes, article 13, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17, refer to the office only as the Usher, and does not specify the colour of his baton of office, however by the time of a statute of 17 July 1717 he is referred to as Green Rod.

36. 1703 Statutes, article 11, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 17 does not assign any duties to Lord Lyon, but merely prescribes his vestments and insignia.

37. For an early illustration, see: Hélyot, P. (1719) 'Histoire des ordres monastiques, religieux et militaires, et des congregations séculières de l'un et de l'autre sexe, qui ont été établis jusqu'à présent' Paris, Vol. VIII, p. 389.

38. 1703 Statutes, article 2, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16

39. Statute of 17 February 1714/15, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 20

40. 1703 Statutes, article 5, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16

41. "Order of Wear". Ceremonial Secretariat, Cabinet Office. 13 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

42. 1703 Statutes, article 3, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 15. In the 1687 statutes the riband was purple-blue; the colour was changed by Queen Anne when she refounded the Order.

43. 1703 Statutes, article 3, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 15 refers to this item of insignia as the medal.

44. 1703 Statutes, article 7, quoted in Statutes (1978), p. 16

45. "Royal Insight: Mailbox". The Royal Household. February 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

46. Debrett's Peerage, p. 82

47. 1703 Statutes, article 11 (Secretary), article 12 (Lord Lyon), article 13 (Usher); Special statute of 10 July 1886 (Dean), Statute of 8 October 1913 (Chancellor), all quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16, 42 and 49–50

48. 1703 Statutes, article 13, quoted in Statutes (1978), pp. 15–16, says only that he carries his "baton of office"

49. Burnett and Hodgson, pp6–7. The 1703 statutes however continue to designate this as the chapel of the Order

50. Paul, pp32–33

51. Innes, p35

52. Cox, N. (1999). "The Coronets of Members of the Royal Family and of the Peerage (The Double Tressure)". Journal of the Heraldry Society of Scotland (22): 8–13. Archived from the original on 21 November 2001.

53. Burnett and Hodgson, p208

54. Innes, p42

55. Burnett and Hodgson, pp. 7–8, and illustrations on pp. 54 ff. Only stall plates for Knights and Ladies appointed after 1911 give the name and date of appointment.

56. Burnett and Hodgson

57. "The Scale of General Precedence in Scotland". Burke's Peerage. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

58. The Crown Office (July 2003). "Forms of Address for use orally and in correspondence". Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original on 6 March 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

59. Innes, p. 47. The circlet does not appear to be commonly used. Neither the collar nor the circlet are used on the stall plates; Burnett and Hodgson on the occasions when the insignia of the Order are mentioned in a grant or matriculation of arms in Burnett and Hodgson (e.g. pp. 134, 138, 174, 180, 198) it is only the collar which is used.

60. "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Symbols: Coats of Arms". The Royal Household. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

61. Woodcock and Robinson, p. 93

References

Printed

• Burnett, C.J.; Hodgson, L. (2001). Stall Plates of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle in the Chapel of the Order within St Giles' Cathedral, The High Kirk of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Heraldry Society of Scotland. ISBN 978-0-9525258-3-7.

• Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage. London: Debrett's Peerage Ltd. 1995.

• Galloway, Peter (2009). The Order of the Thistle. Spink & Son Ltd. ISBN 978-1-902040-92-9.

• Innes of Learney, T. (1956). Scots heraldry; a practical handbook on the historical principles and modern application of the art and science (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

• Mackey, A.G.; Haywood, H.L. (1946). Encyclopedia of Freemasonry. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-4719-5.

• Nicolas, N. H. (1842). History of the orders of knighthood of the British empire, of the order of the Guelphs of Hanover; and of the medals, clasps, and crosses, conferred for naval and military service, Vol iii. London.

• Paul, J.B. (1911). The knights of the Order of the Thistle: a historical sketch by the Lord Lyon King of Arms, and a descriptive sketch of their chapel by J. Warrack. Edinburgh.

• Order of the Thistle (1978). Statutes of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle: revived by His Majesty King James II of England and VII of Scotland and again revived by Her Majesty Queen Anne. Edinburgh.

• Woodcock, T.; Robinson, J.M. (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211658-1.

Online

• "The Monarchy Today: Queen and Public: Honours: The Order of the Thistle". The official website of the British Monarchy. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

• "Royal Insight: Mailbox". The Royal Household. February 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2007.

• "The Scale of General Precedence in Scotland". Burke's Peerage. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.