Charles Webster Leadbeaterby Wikipedia

Accessed: 12/13/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

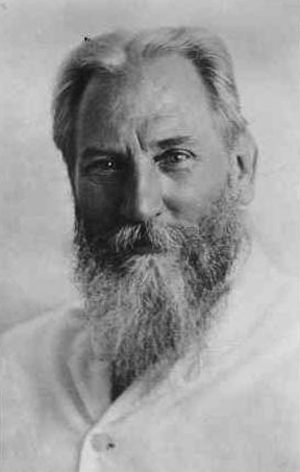

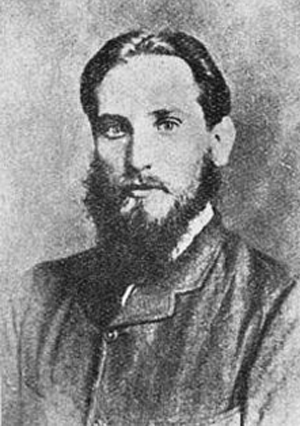

Charles Webster Leadbeater

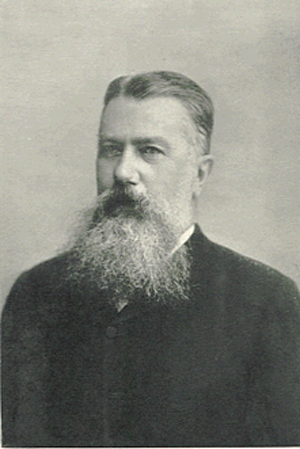

Leadbeater in 1914 (age 60)

Born 16 February 1854

Stockport, Greater Manchester, UK

Died 1 March 1934 (aged 80)

Perth, Australia

Known for Theosophist and writer

Charles Webster Leadbeater (/ˈlɛdˌbɛtər/; 16 February 1854 – 1 March 1934) was a member of the Theosophical Society, author on occult subjects and co-initiator with J. I. Wedgwood of the Liberal Catholic Church.

Originally a priest of the Church of England, his interest in spiritualism caused him to end his affiliation with Anglicanism in favour of the Theosophical Society, where he became an associate of Annie Besant. He became a high-ranking officer of the Society, but resigned in 1906 amid a sex scandal involving adolescent boys. He was readmitted after his champion Annie Besant became President and remained one of its leading members until his death in 1934, writing at least 69 books and pamphlets and maintaining regular speaking engagements, but continued to be involved in scandals.

Early lifeLeadbeater was born in Stockport, Cheshire, in 1854. His father, Charles Sr., was born in Lincoln and his mother Emma was born in Liverpool. He was an only child. By 1861 the family had relocated to London, where his father was a railway contractor's clerk.[1][non-primary source needed]

In 1862, when Leadbeater was eight years old, his father died from tuberculosis. Four years later a bank in which the family's savings were invested became bankrupt. Without finances for college, Leadbeater sought work soon after graduating from high school in order to provide for his mother and himself. He worked at various clerical jobs.[2] During the evenings he became largely self-educated. For example, he studied astronomy and had a 12-inch reflector telescope (which was very expensive at the time) to observe the heavens at night. He also studied French, Latin and Greek.

An uncle, his father's brother-in-law, was the well-known Anglican cleric William Wolfe Capes. By his uncle's influence, Leadbeater was ordained an Anglican priest in 1879 in Farnham by the Bishop of Winchester. By 1881, he was living with his widowed mother at Bramshott in a cottage which his uncle had built, where he is listed as "Curate of Bramshott".[3] He was an active priest and teacher who was remembered later as "a bright and cheerful and kindhearted man".[4] About this time, after reading about the séances of reputed medium Daniel Dunglas Home (1833–1886), Leadbeater developed an active interest in spiritualism.

Theosophical SocietyHis interest in Theosophy was stimulated by A.P. Sinnett's Occult World, and he joined the Theosophical Society in 1883. The next year he met Helena Petrovna Blavatsky when she came to London; she accepted him as a pupil and he became a vegetarian.[5]

Around this time he wrote a letter to Kuthumi, asking to be accepted as his pupil.[6] Shortly afterward, an encouraging response influenced him to go to India; he arrived at Adyar in 1884. He wrote that while in India, he had received visits and training from some of the "Masters" that according to Blavatsky were the inspiration behind the formation of the Theosophical Society, and were its hidden guides.[7] This was the start of a long career with the Theosophical Society.

Headmaster in CeylonDuring 1885, Leadbeater traveled with Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), first President of the Theosophical Society, to Burma and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In Ceylon they founded the English Buddhist Academy, with Leadbeater staying there to serve as its first headmaster under very austere conditions.[8] This school gradually expanded to become Ananda College, which now has more than 6,000 students and has a building named for Leadbeater.[9] After Blavatsky left Adyar in 1886 to return to Europe and finish writing The Secret Doctrine, Leadbeater claimed to have developed clairvoyant abilities.[10]

Return to EnglandIn 1889, Sinnett asked Leadbeater to return to England to tutor his son and George Arundale (1878–1945). He agreed and brought with him one of his pupils, Curuppumullage Jinarajadasa (1875–1953). Although struggling with poverty himself, Leadbeater managed to send both Arundale and Jinarajadasa to Cambridge University. Both would eventually serve as International presidents of the Theosophical Society.

Meeting with Annie BesantAfter H. P. Blavatsky's death in 1891, Annie Besant, an English social activist, took over leadership of the Theosophical Society along with Colonel Olcott.[11] Besant met Leadbeater in 1894. The next year she invited him to live at the London Theosophical Headquarters, where H.P. Blavatsky died in 1891.[12]

Writing and speaking careerLeadbeater wrote 69 books and pamphlets during the period from 1895 to his death in 1934, many of which continued to be published until 1955.[13] Two noteworthy titles, Astral Plane and the Devachanic Plane (or The Heaven World) both of which contained writings on the realms the soul passes through after death.

"For the first time among occultists, a detailed investigation had been made of the Astral Plane as a whole, in a manner similar to that in which a botanist in an Amazonian jungle would set to work in order to classify its trees, plants and shrubs, and so write a botanical history of the jungle. For this reason the little book, The Astral Plane, was definitely a landmark, and the Master as Keeper of the Records desired to place its manuscript in the great Museum." [14]

Highlights of his writing career included addressing topics such as: the existence of a loving God, The Masters of Wisdom, what happens after death, immortality of the human soul, reincarnation, Karma or the Law of Consequence, development of clairvoyant abilities, the nature of thought forms, dreams, vegetarianism, Esoteric Christianity[15]

He also became one of the best known speakers of the Theosophical Society for a number of years[16] and served as Secretary of the London Lodge.[17]

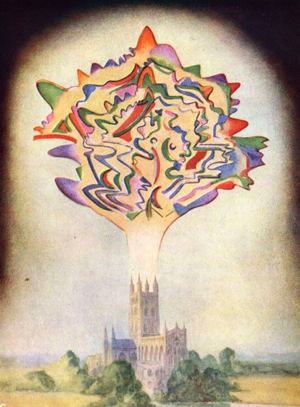

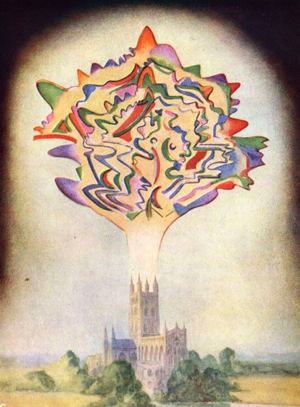

Clairvoyance "Seeing" of music: a piece by Gounod (from a book Thought-Forms by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater).

"Seeing" of music: a piece by Gounod (from a book Thought-Forms by Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater).Clairvoyance is a book by Leadbeater originally published in 1899 in London.[18][19] It is a study of a belief in seeing beyond the realms of ordinary sight.[20][21][22] The author mainly appeals readers "convinced of the existence of clairvoyance and familiar with theosophical terms."[23] Leadbeater claims that the "power to see what is hidden from ordinary physical sight" is an extension of common reception, and "describes a wide range of phenomena."[23][note 1][note 2]

Contents1. What clairvoyance is.

2. Simple clairvoyance: full.

3. Simple clairvoyance: partial.

4. Clairvoyance in space: intentional.

5. Clairvoyance in space: semi-intentional.

6. Clairvoyance in space: unintentional.

7. Clairvoyance in time: the past.

8. Clairvoyance in time: the future.

9. Methods of development.[26][27]

Methods of development Leadbeater writes about the importance of control over thinking and the need for skill "to concentrate thought":

"Let a man choose a certain time every day—a time when he can rely upon being quiet and undisturbed, though preferably in the daytime rather than at night—and set himself at that time to keep his mind for a few minutes entirely free from all earthly thoughts of any kind whatever and, when that is achieved, to direct the whole force of his being towards the highest spiritual ideal that he happens to know. He will find that to gain such perfect control of thought is enormously more difficult than he supposes, but when he attains it, it cannot but be in every way most beneficial to him, and as he grows more and more able to elevate and concentrate his thought, he may gradually find that new worlds are opening before his sight."[28][note 3] [note 4]

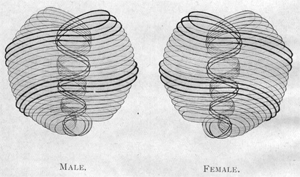

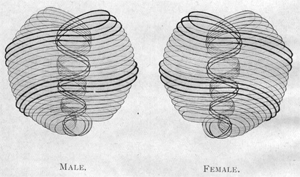

Author's personal experience "Ultramicroscopic seeing" of matter: the "ultimate" physical atom (from Occult Chemistry by A. Besant and C. W. Leadbeater).

"Ultramicroscopic seeing" of matter: the "ultimate" physical atom (from Occult Chemistry by A. Besant and C. W. Leadbeater).Professor Robert Ellwood wrote that from 1884 to 1888 Leadbeater undertook a course of meditation practice "which awakened his clairvoyance."[25] One day when the Master Kuthumi visited, he asked whether Leadbeater had ever attempted "a certain kind of meditation connected with the development of the mysterious power called kundalini."[33][34] The Master recommended him to make a "few efforts along certain lines," and told him that he would himself "watch over those efforts to see that no danger should ensue." Leadbeater accepted the offer of the Master and became "day after day" working on this kind of meditation.[35] He worked on the task assigned to him for forty-two days, and it seemed to him that he was already on the verge of achieving a result when Kuthumi intervened and "performed the final act of breaking through which completed the process," and enabled Leadbeater thereafter to use astral sight while as he was retaining full consciousness in the physical body. It is equivalent to saying that "the astral consciousness and memory became continuous," whether the physical body was awake or asleep.[36][37][note 5]

Possible application In the chapter "Simple Clairvoyance: Full" the author argues that an occultist-clairvoyant can "see" the smallest particles of matter, for example, a molecule or atom, magnificating them "as though by a microscope."[40][note 6][note 7] In the chapter "Clairvoyance in Time: The Past" Leadbeater claims that before the historian who is in "full possession of this power" open up wonderful possibilities:

"He has before him a field of historical research of most entrancing interest. Not only can he review at his leisure all history with which we are acquainted, correcting as he examines it the many errors and misconceptions which have crept into the accounts handed down to us; he can also range at will over the whole story of the world from its very beginning."[43][note 8][note 9]

New editions and translations The book was reprinted several times and translated into some European languages. Second edition of the book was published in 1903, and third—in 1908.[18][note 10]

Resignation from the Theosophical SocietyIn 1906, critics were angered to learn that Leadbeater had given advice to boys under his care that encouraged masturbation as a way to relieve obsessive sexual thoughts. Leadbeater acknowledged that he had given this advice to a few boys approaching maturity who came to him for help. He commented, "I know that the whole question of sex feelings is the principal difficulty in the path of boys and girls, and very much harm is done by the prevalent habit of ignoring the subject and fearing to speak of it to young people. The first information about it should come from parents or friends, not from servants or bad companions."[45]

The revelations regarding Leadbeater's advice and resulting suspicion that he was sexually abusive prompted several members of the Theosophical Society to ask for his resignation. The Society held proceedings against him in 1906. Annie Besant, elected president of the Society in 1907, later stated in his defense:

"The so-called trial of Mr Leadbeater was a travesty of justice. He came before Judges, one of whom had declared before hand that 'he ought to be shot'; another, before hearing him, had written passionate denunciations of him, a third and fourth had accepted, on purely psychic testimony, unsupported by any evidence, the view that he was grossly immoral, and a danger to the Society..."[46]

Charges of misconduct that went beyond the advice he admitted giving were never proven. He nevertheless resigned.

Readmission to the Theosophical SocietyAfter Olcott died in 1907, Annie Besant became president of the society following a political struggle. By the end of 1908, the International Sections voted for Leadbeater's readmission. He accepted and came to Adyar on 10 February 1909. At the time, Besant referred to Leadbeater as a martyr who was wronged by her and by the Theosophical Society, saying that "never again would a shadow come between her and her brother Initiate".[47]

Discovery of KrishnamurtiIn 1909 Leadbeater encountered fourteen-year-old Jiddu Krishnamurti at the private beach of the Theosophical Society headquarters at Adyar. Krishnamurti's family lived next to the compound; his father, a long-time Theosophist, was employed by the Society. Leadbeater believed Krishnamurti to be a suitable candidate for the "vehicle" of the World Teacher, a reputed messianic entity[48] whose imminent appearance he and many Theosophists were expecting. The proclaimed savior would then usher in a new age and religion.[49]

Leadbeater assigned the pseudonym Alcyone to Krishnamurti and under the title "Rents in the Veil of Time", he published 30 reputed past lives of Alcyone in a series in The Theosophist magazine beginning in April 1910. "They ranged from 22,662 BC to 624 AD ... Alcyone was a female in eleven of them."[50]

Leadbeater stayed in India until 1915, overseeing the education of Krishnamurti; he then relocated to Australia. During the late 1920s, Krishnamurti disavowed the role that Leadbeater and other Theosophists expected him to fulfil.[51] He disassociated himself from the Theosophical Society and its doctrines and practices,[52] and during the next six decades became known as an influential speaker on philosophical and religious subjects.

Australia and The Science of the SacramentsLeadbeater moved to Sydney in 1915. He was responsible for the construction of the Star Amphitheatre at Balmoral Beach in 1924. While in Australia he became acquainted with J. I. Wedgwood, a Theosophist and bishop in the Liberal Catholic Church who initiated him into Co-Masonry in 1915 and later consecrated him as a bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church in 1916.

Public interest in Theosophy in Australia and New Zealand increased greatly as a result of Leadbeater's presence there and Sydney became comparable to Adyar as a centre of Theosophical activity.[53]

The Manor, Sydney, Australia, where Leadbeater stayed from 1922 to 1929

The Manor, Sydney, Australia, where Leadbeater stayed from 1922 to 1929In 1922, the Theosophical Society began renting a mansion known as The Manor in the Sydney suburb of Mosman. Leadbeater took up residence there as the director of a community of Theosophists. The Manor became a major site and was regarded as "the greatest of occult forcing houses".[54] There he accepted young women students. They included Clara Codd, future President of the Theosophical Society in America, clairvoyant Dora van Gelder, another future President of the Theosophical Society in America who during the 1970s also worked with Delores Krieger to develop the technique of Therapeutic touch, and Mary Lutyens, who would later write an authorized Krishnamurti biography.[55] Lutyens stayed there in 1925, while Krishnamurti and his brother Nitya stayed at another house nearby. The Manor became one of three major Theosophical Society sites, the others being at Adyar and the Netherlands. The Theosophical Society bought The Manor in 1925 and during 1951 created The Manor Foundation Ltd, to own and administer the house, which is still used by the Society.[56]

It was also during his stay in Australia that Leadbeater became the Presiding Bishop of the Liberal Catholic Church and co-wrote the liturgy book for the church which is still in use today. The work represents an adaptation of the Roman Catholic liturgy of his time, for which Leadbeater sought to remove what he regarded as undesirable elements, such as (in his view) the blatant anthropomorphisms and expressions of the fear and wrath of God, which he regarded "as derogatory alike to the idea of a loving Father and to the men He has created in His own image." "If Christians", he wrote, "had been content to take what Christ taught of the Father in heaven, they would never have saddled themselves with the jealous, angry, bloodthirsty Jehovah of Ezra, Nehemiah and the others – a god that needs propitiating and to whose 'mercy' constant appeals must be made."[57]

Thus the Credo of the Liberal Catholic Church liturgy written by Leadbeater reads:

"We believe that God is Love and Power and Truth and Light; that perfect justice rules the world; that all His sons shall one day reach His Feet, however far they stray. We hold the Fatherhood of God, the Brotherhood of man; we know that we do serve Him best when best we serve our brother man. So shall His blessing rest upon us and peace for evermore. Amen."[58]

Previously Leadbeater had written on the energies of the Christian sacraments in The Science of the Sacraments: An Occult and Clairvoyant Study of the Christian Eucharist, one of the most significant works of Christian esotericism. In his prologue to the latest edition of this book, John Kersey refers to the Eucharist proposed by Leadbeater as "a radical reinterpretation of the context of the Eucharist seen within a theological standpoint of esoteric magic and universal salvation; it is Catholicism expressing the love of God to the full without the burdens of needless guilt and fear, and the false totem of the temporal powers of the church."[59]

How Theosophy Came to MeIt is an autobiographical book by Leadbeater; it was first published in 1930.[60]

Spiritualism and Theosophy Leadbeater tells that he was interested always in a variety of anomal phenomena, and if in any newspaper report it was said about the appearance of ghosts or other curious events in the troubled house, he had been going immediately to this location. In a large number of instances it was a blank — "either there was no evidence worth mentioning, or the ghost declined to appear when he was wanted." Sometimes, however, there were signs of some success, and soon had collected "an amount of direct evidence" that could easily convince him, if would had needed, as he said, in order it was convincing.[61]

In attitude to spiritualism Leadbeater was initially set up quite skeptical, but still one day decided to conduct an experiment with his mother and a some small boy, who, as they later discovered, "was a powerful physical medium." They had a small round table with a leg in the middle and silk hat, which they put on the table, and then put their "hands upon its brim as prescribed." Surprisingly the hat gave "a gentle but decided half-turn on the polished surface of the table," and then began to spin so vigorously that it was difficult to keep on it their hands.[62]

Further, the author describes the events as follows:

"Here was my own familiar silk hat, which I had never before suspected of any occult qualities, suspending itself mysteriously in the air from the tips of our fingers, and, not content with that defiance of the laws of gravity on its own account, attaching a table to its crown and lifting that also! I looked down to the feet of the table; they were about six inches from the carpet, and no human foot was touching them or near them! I passed my own foot underneath, but there was certainly nothing there—nothing physically perceptible, at any rate."[63][64]

The author says that he was not himself thinking of the phenomenon "in the least as a manifestation from the dead," but only as the disclosure of some unknown new force.[65][note 11]

Leadbeater says that the first theosophical book that fell into his hands was Sinnett's The Occult World. Histories contained in this book were for him very interested, but "its real fascination lay in the glimpses which it gave of a wonderful system of philosophy and of a kind of inner science which really seemed to explain life rationally and to account for many phenomena," which Leadbeater has watched. He had written to Sinnett, who invited him to come to London in order to meet.[69][70][note 12] The author tells that when he had claimed of joining the Society, Sinnett "became very grave and opined that that would hardly do," since Leadbeater was a clergyman. He had asked him why the Society discriminates against members according to the cloth. Sinnett replied: "Well, you see, we are in the habit of discussing every subject and every belief from the beginning, without any preconceptions whatever; and I am afraid that at our meetings you would be likely to hear a great deal that would shock you profoundly."[71] But most members of the Council of the London Lodge approved the joining of Leadbeater. He was joined into the Theosophical Society together with professor Crookes and his wife. On that day at the Lodge meeting "have been some two hundred people present," including such as professor Myers, Stainton Moses and others.[72][note 13]

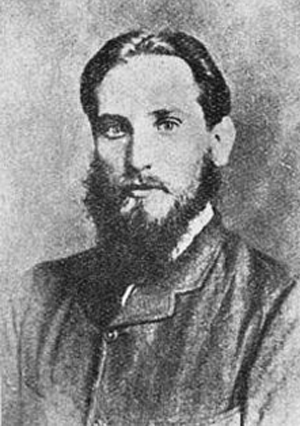

Blavatsky Blavatsky

BlavatskyIn a section I Meet Our Founder Leadbeater describes the "triumphant" appearance of Blavatsky at a meeting of the London Lodge of the British Theosophical Society, where he saw her for the first time.[note 14]

"Suddenly and sharply the door opposite to us opened, and a stout lady in black came quickly in and seated herself at the outer end of our bench. She sat listening to the wrangling on the platform for a few minutes, and then began to exhibit distinct signs of impatience. As there seemed to be no improvement in sight, she then jumped up from her seat, shouted in a tone of military command the one word 'Mohini!'[note 15] and then walked straight out of the door into the passage. The stately and dignified Mohini came rushing down that long room at his highest speed, and as soon as he reached the passage threw himself incontinently flat on his face on the floor at the feet of the lady in black. Many people arose in confusion, not knowing what was happening; but a moment later Mr. Sinnett himself also came running to the door, went out and exchanged a few words, and then, re-entering the room, he stood up on the end of our bench and spoke in a ringing voice the fateful words: 'Let me introduce to the London Lodge as a whole—Madame Blavatsky!' The scene was indescribable; the members, wildly delighted and yet half-awed at the same time, clustered round our great Founder, some kissing her hand, several kneeling before her, and two or three weeping hysterically."[75][note 16]

According to the author, the impression which Blavatsky made "was indescribable." She was looking straight through man, and obviously saw everything that was in one, and not everyone liked it. Sometimes Leadbeater heard from her very unpleasant revelations about those with whom she spoke. He's writing: "Prodigious force was the first impression, and perhaps courage, outspokenness, and straightforwardness were the second."[76]

Leadbeater writes that Blavatsky was the best interlocutor he had ever met: "She had the most wonderful gift for repartee; she had it almost to excess, perhaps." She also had knowledge of all sorts of things that relate to very different directions. She always had something to say, and it was never empty talk. She traveled a lot, and mostly on little-known places, and did not forget anything. She has been remembering even the most insignificant cases that had happened to her. She was a wonderful storyteller, who knew how to give a good story and make the right impression. "Whatever else she may have been, she was never commonplace. She always had something new, striking, interesting, unusual to tell us."[77][78]

In connection with the accusations of Blavatsky's enemies in her alleged fraud, cheating, forgery, Leadbeater writes: "The very idea of deception of any sort in connection with Madame Blavatsky is unthinkable to anyone who knew her... Her absolute genuineness was one of the most prominent features of her marvellously complex character."[77]

Letters from Kuthumi The author tells that during the study of spiritualism his greatest confidant was medium Eglinton. On one of the spiritualistic séances Eglinton's spirit guide "Ernest" agreed to take Leadbiter's letter in order to transmit it to the Master Kuthumi. In this letter the author "with all reverence" wrote that ever since he had first heard of theosophy his one desire had been to place himself under Master as a chela (pupil).[69][79][note 17] He also wrote about his current circumstances and has asked, has a pupil need to be in India within seven years of probation.[69][82]

The response from the Master Kuthumi has arrived a few months. The mahatma said that to be in India for seven years of probation isn't necessary—a chela can pass them anywhere. He offered to work for a few months at Adyar to see, may Leadbeater to be as a servant of the headquarters, and added a significant remark: "He who would shorten the years of probation has to make sacrifices for theosophy."[83][84][note 18]

The letter was ended with the following words:

"You ask me — 'what rules I must observe during this time of probation, and how soon I might venture to hope that it could begin'. I answer: you have the making of your own future, in your own hands as shown above, and every day you may be weaving its woof. If I were to demand that you should do one thing or the other, instead of simply advising, I would be responsible for every effect that might flow from the step and you acquire but a secondary merit. Think, and you will see that this is true. So cast the lot yourself into the lap of Justice, never fearing but that its response will be absolutely true.

Chelaship is an educational as well as probationary stage and the chela alone can determine whether it shall end in adeptship or failure. Chelas from a mistaken idea of our system too often watch and wait for orders, wasting precious time which should be taken up with personal effort. Our cause needs missionaries, devotees, agents, even martyrs perhaps. But it cannot demand of any man to make himself either. So now choose and grasp your own destiny, and may our Lord's the Tathâgata's memory aid you to decide for the best."[83][85]

After reading the letter, Leadbeater hurried back to London, not doubting his decision to devote his life to the service for the Masters. He hoped to send his answer with the help of Blavatsky. At first she refused to read the letter of the mahatma, saying that such cases are purely private, but as a result of Leadbeater's insistence, she finally read and asked him what answer he had decided to give. He said he wanted to quit his priesthood career and go to India, fully dedicating himself to a serving the Masters. Blavatsky assured him that, because of her constant connection with the mahatma, he already knows about Leadbeater's decision, and will give his answer in the near time. She warned that he need to stay close to her until he get an answer.[83][86][note 19] The author tells:

"She (Blavatky) was talking brilliantly to those who were present, and rolling one of her eternal cigarettes, when suddenly her right hand was jerked out towards the fire in a very peculiar fashion, and lay palm upwards. She looked down at it in surprise, as I did myself, for I was standing close to her, leaning with an elbow on the mantel-piece: and several of us saw quite clearly a sort of whitish mist form in the palm of her hand and then condense into a piece of folded paper, which she at once handed to me, saying: 'There is your answer'."[83][87]

It was a very short note, and read it as follows:

"Since your intuition led you in the right direction and made you understand that it was my desire you should go to Adyar immediately, I may say more. The sooner you go the better. Do not lose one day more than you can help. Sail on the 5th if possible. Join Upasika[note 20] at Alexandria. Let no one know that you are going, and may the blessing of our Lord and my poor blessing shield you from every evil in your new life. Greeting to you, my new chela.

−K.H."[83][89][note 21]

In section A Message the author tells how Blavatsky received in the going train car from the mahatma Kuthumi a note, which had several words intended for him: "Tell Leadbeater that I am satisfied with his zeal and devotion."[90]

Leadbeater claims that in early days of the Theosophical Society commissions and orders from the mahatmas were common, and members lived at a "level of splendid enthusiasm which those who have joined since Madame Blavatsky’s death can hardly imagine."[91]

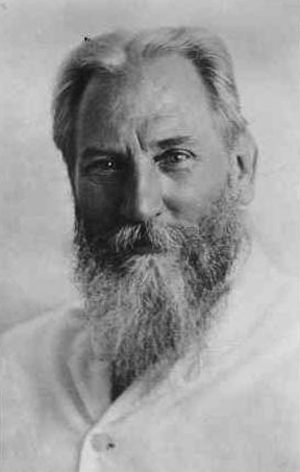

Tisarana and pansil Leadbeater in Adyar, 1885

Leadbeater in Adyar, 1885During the few weeks of traveling from Egypt to India, Blavatsky radically transformed the personality of Leadbeater, who was "an ordinary lawn-tennis-playing curate—well-meaning and conscientious... incredibly shy and retiring," making him a worthy disciple of mahatmas.[92][note 22]

During a brief stop in Ceylon, Blavatsky who together with Olcott even earlier became a Buddhist invited Leadbeater to follow the example of the founders of the Theosophical Society. The author writes that she believed that since he was a Christian priest, his public demonstration of Buddhism could convince both Hindus and Buddhists of the honesty of his intentions and would allow him to become more useful for the mahatmas.[94]

After three times pronouncing of a praise to the Lord Buddha: "I reverence the Blessed One, the Holy One, the Perfect in Wisdom," Leadbeater recitated on the Pali sacred formula of the Tisarana and then the Pancha Sila.[95][note 23]

Upon arrival in Madras, Blavatsky has spoke in front of the Hindustanies who filled the room, indignant at the actions of the Christian missionaries.

"When at last she was allowed to speak, she began very well by saying how touched she was by this enthusiastic reception, and how it showed her what she had always known, that the people of India would not accept tamely these vile, cowardly, loathsome and utterly abominable slanders, circulated by these unspeakable—but here she became so vigorously adjectival that the Colonel hurriedly intervened, and somehow persuaded her to resume her seat, while he called upon an Indian member to offer a few remarks."[96][note 24]

The author informs that his life at Adyar was ascetic; there were practically no servants, except two gardeners and a boy who has been working in the office. Leadbeater ate every day porridge from wheat flakes, which he brewed himself, also he was being brought milk and bananas.[98] At the headquarters of the Society, Leadbeater had been taking post of the recording secretary, since that allowed him to remain in the center of the Theosophical movement, where, as he knew, in the materialized forms, the Masters were often shown themselves.[99][note 25]

One day the author had met with the mahatma Kuthumi on the roof of the headquarters, next to Blavatsky's room. He was near a balustrade which "running along the front of the house at the edge of the roof" when the Master "materialized," stepping over the balustrade, as if before that he had been flying through the air. Leadbeater says:

"Naturally I rushed forward and prostrated myself before Him; He raised me with a kindly smile, saying that though such demonstrations of reverence were the custom among the Indian peoples, He did not expect them from His European devotees, and He thought that perhaps there would be less possibility of any feeling of embarrassment if each nation confined itself to its own methods of salutation."[100]

Occult training Subba Row

Subba RowThe author claims that when he arrived in India, he did not have any clairvoyant abilities. One day when Kuthumi "honoured" him with a visit, he asked whether Leadbeater had ever attempted "a certain kind of meditation connected with the development of the mysterious power called kundalini."[34][note 26] Leadbeater had heard of that power, but thinked it to be certainly out of reach for Western people. Yet Kuthumi recommended him to make a "few efforts along certain lines," and told him that he would himself "watch over those efforts to see that no danger should ensue." He accepted the offer of the Master and became "day after day" working on this kind of meditation. He was told that on average it would take forty days, if he do it constantly and vigorously.[35]

Leadbeater worked on the task assigned to him for forty-two days, and it seemed to him that he was already on the verge of achieving a result when Kuthumi intervened and "performed the final act of breaking through which completed the process," and enabled the author thereafter to use astral sight while as he was retaining full consciousness in the physical body. It is equivalent to saying that "the astral consciousness and memory became continuous," whether the physical body was awake or asleep.[102][37][note 27]

A lot of care and work was spent on occult training of the author by the Master Djwal Khul. Leadbeater tells:

"Over and over again He would make a vivid thought-form, and say to me: 'What do you see?' And when I described it to the best of my ability, would come again and again the comment: 'No, no, you are not seeing true; you are not seeing all; dig deeper into yourself, use your mental vision as well as your astral; press just a little further, a little higher.'"[103]

To participate in the training of Leadbeater, often came to headquarters swami Subba Row, "our great pandit," as the author calls him. And Leadbeater claims that he will forever remain an obligor to these "two great people" — Djwal Khul and Subba Row — for all the help which they gave him "at this critical stage" of his life.[104]

LegacyLeadbeater remains well-known and influential in New Age circles for his many works based on his clairvoyant investigations of life, including such books as Outline of Theosophy, Astral Plane, Devachanic Plane, The Chakras and Man, Visible and Invisible dealing with, respectively, the basic principles of theosophy, the two higher worlds humanity passes through after "death", the chakra system, and the human aura.

His writings on the sacraments and Christian esotericism remain popular, with a constant stream of new editions and translations of his magnum opus The Science of the Sacraments. His liturgy book is still used by many Liberal and Independent Catholic Churches across the world.

Selected writings• Dreams (What they are and how they are caused) (1893)

• Theosophical Manual Nº5: The Astral Plane (Its Scenery, Inhabitants and Phenomena) (1896)

• Theosophical Manual Nº6: The Devachanic Plane or The Heaven World Its Characteristics and Inhabitants (1896)

• Invisible Helpers (1896)

• Reincarnation (1898)

• Our Relation to Our Children (1898)

• Clairvoyance (1899)

• Thought Forms (with Annie Besant) (1901)

• An Outline of Theosophy (1902)

• Man Visible and Invisible (1902)

• Some Glimpses of Occultism, Ancient and Modern (1903)

• The Christian Creed (1904)

• Occult Chemistry (with Annie Besant) (1908)

• The Inner Life (1911)

• The Perfume of Egypt and Other Weird Stories (1911)

• The Power and Use of Thought (1911)

• The Life After Death and How Theosophy Unveils It (1912)

• A Textbook of Theosophy (1912)

• Man: Whence, How and Whither (with Annie Besant) (1913)

• Vegetarianism and Occultism (1913)

• The Hidden Side of Things (1913)

• Australia & New Zealand: Home of a new sub-race (1916)

• The Monad and Other Essays Upon the Higher Consciousness (1920)

• The Inner Side Of Christian Festivals (1920)

• The Science of the Sacraments (1920)

• The Lives of Alcyone (with Annie Besant) (1924)

• The Liturgy According to the Use of the Liberal Catholic Church (with J.I. Wedgwood) (Second Edition) (1924)

• The Masters and the Path (1925)

• Talks on the Path of Occultism (1926)

• Glimpses of Masonic History (1926) (later pub 1986 as Ancient Mystic Rites)

• The Hidden Life in Freemasonry (1926)

• The Chakras (1927) (published by the Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton, Illinois, USA)

• Spiritualism and Theosophy Scientifically Examined and Carefully Described (1928)

• The Noble Eightfold Path (1955)

• Messages from the Unseen (1931)

See also• Chakras

• Clairvoyance

• Christian mythology

• K.H. Letters to C.W. Leadbeater

• Reincarnation

• Root race

• Theosophy and Christianity

• Theosophy and visual arts

Notes1. When the Theosophical Society was created the investigation "the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man" was proclaimed its third major task.[24]

2. Professor Robert Ellwood stated, "The key to Leadbeater's teaching and theosophical style is the idea of clairvoyance, the capacity to see things that are hidden from ordinary eyes."[25]

3. "He (Leadbeater) suggests that if the aspirant should concentrate on living the pure and unselfish life and practice meditation, then possibly some form of psychic power may emerge spontaneously with little risk."[29]

4. Professor Radhakrishnan wrote: "By following the principles of the Yoga, such as heightening the power of concentration, arresting the vagaries of mind by fixing one's attention on the deepest sources of strength, one can master one's soul even as an athlete masters his body. The Yoga helps us to reach a higher level of consciousness, through a transformation of the psychic organism, which enables it to get beyond the limits set to ordinary human experience."[30] Uncommon power of the senses, by which man "can see and hear at a distance, follow as a result of concentration."[31] According to Buddhist philosophy, extra-sensory abilities achieved primarily "through meditation and wisdom."[32]

5. "The awakening of the kundalini arouses an intense heat, and its progress through the cakras is manifested by the lower part of the body becoming as inert and cold as a corpse, while the part—through which the kundalini passes—is burning hot."[38] Professor Olav Hammer wrote that in the most authoritative interpretation chakras were introduced to the Western audience by the Theosophists, mainly by Leadbeater.[39]

6. "The power of 'magnification' is said to be one of the powers, or siddhis, of the great yogi, meaning that he is able to look at small objects and see them greatly enlarged."[41]

7. "Leadbeater had first used his psychic powers in delving in to the atom at the request of Mr. Sinnett, and thus discovered that he possessed 'ultramicroscopic' vision."[42]

8. "Through concentration on the threefold modifications which all objects constantly undergo, we acquire the power to know the past, present and the future."[31]

9. See also: Man: Whence, How and Whither#Explorations of past lives

10. "19 editions published between 1899 and 2014 in 5 languages and held by 23 WorldCat member libraries worldwide."[44]

11. Tillett stated: "Leadbeater's interest in spiritualism increased after the death of his mother on May 24, 1882."[66] Also Matley wrote that Leadbeater has been on "few spiritualistic séances" of the mediums Husk[67] and Eglinton.[68]

12. His new life had started in 1883, when he has had read Sinnett's The Occult World. It had led the "young curate" to contact with the Theosophical Society in London.[25]

13. Leadbeater "was welcomed into the London Lodge on February 21, 1884."[25]

14. Senkevich wrote: "The appearance of Blavatsky at the meeting was triumphant, some of its participants fell down in front of her to their knees.... At this re-election meeting she was deservedly represented by the queen of occultism, all were obeying her will unquestioningly."[73]

15. Mohini Mohun Chatterji (1858–1936) was a private secretary to Henry Steel Olcott.[74]

16. "Then, on April 7, 1884, Leadbeater met Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott at a turbulent election meeting of the London Lodge. Deeply impressed by Blavatsky, from that day on Leadbeater's commitment tilted more and more away from Anglicanism and toward theosophy."[25]

17. Goodrick-Clarke wrote that "the very concept of the Masters" is the Rosicrucian idea of "invisible and secret adepts, working for the advancement of humanity."[80] And Tillett stated: "The concept of Masters or Mahatmas as presented by HPB involved a mixture of western and eastern ideas; she located most of them in India or Tibet. Both she and Colonel Olcott claimed to have seen and to be in communication with Masters. In Western occultism the idea of 'Supermen' has been found in such schools as... the fraternities established by de Pasqually and de Saint-Martin."[81]

18. Leadbeater "received a letter from the Master Koot Hoomi (K.H.) in October 31, 1884, just prior to Blavatsky's return to India. Leadbeater responded by writing a letter on November 1 in which he offered to give up his career in the Church and go to India with her to serve theosophy."[25]

19. Leadbeater passed the mahatma's letter to Blavatsky in London and asked her to read it, that she did unwillingly, since she believed so it was a confidential correspondence. He "then accompanied her to the home of the Cooper-Oakleyswhere, 'after midnight' (i.e., early November 2, 1884) a reply materialized on Blavatky's upturned hand while Leadbeater was watching."[25]

20. "Upasika is a name often used for H.P.B. in the Letters; the word is from Buddhism, where it denotes a Lay Disciple."[88]

21. With this note mahatma ordered to Leadbeater to leave England immediately, since it was his desire, and to join Blavatsky in Alexandria. "This he did, precipitously resigning his priesthood, putting his affairs in order, and sailing for India on November 5."[25]

22. Senkevich wrote: "The last trip of Blavatsky to India was described in memoirs by Charles Leadbeater, who was a young rural Anglican priest that had just joined the Theosophical Society. He had been accompanying Blavatsky from England to Port Said, from there — to Colombo, and then — to Madras."[93]

23. Leadbeater "took pansil, formally becoming a Buddhist, in Colombo, Ceylon, and then arrived in Adyar in December 1884."[25]

24. "As soon as the audience was quiet, Blavatsky began her fierce speech directed against Christian missionaries. In it, she used such an obscene word that Olcott jumped up in terror and looked pleadingly at her."[97]

25. "From 1884 to 1888, Leadbeater was recording secretary of the Theosophical Society, assistant to Olcott and a student of the Ancient Wisdom called theosophy."[25]

26. "Leadbeater and later Esotericists up to and including New Age writers have reinterpreted kundalini as simply a form of energy."[101]

27. Robert Ellwood wrote that from 1884 to 1888 Leadbeater has had a course of meditation practice "which awakened his clairvoyance."[25]

References[edit]

1. 1861 Census of England

2. Tillett, Gregory John; Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934, A Biographical Study, 1986,

http://hdl.handle.net/2123/16233. 1881 Census of England

4. Warnon, Maurice H., "Charles Webster Leadbeater, Biographical Notes". "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

5. Lutyens, Mary (1975). Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux. p. 13. ISBN 0-374-18222-1.

6. How Theosophy Came To Me, C. W. Leadbeater, Chpt 2 – A letter to the master, The Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai 600 020, India, First Edition 1930

7. Leadbeater, C.W. (1930). "How Theosophy Came To Me". The Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 26 March2008.

8. Lutyens 1975 p. 13.

9. Oliveira, Pedro, CWL Bio, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 June 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

10. How Theosophy Came To Me, C. W. Leadbeater, chpt 9 – Unexpected development; Psychic Training, The Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai 600 020, India, First Edition 1930

11. Theosophical Society – World Headquarters, Adyar, Channai, India [1].

12. Astral Plane, CW Leadbeater, p. xviii,

http://anandgholap.net/Astral_Plane-CWL.htm13. Blavatskyarchives.com, "A Chronological Listing of C.W. Leadbeater's Books and Pamphlets", [2]

14. Astral Plane, CW Leadbeater[3]; Introduction by C. JINARAJADASA, p. xviii

15. [4]

16. Warnon, Maurice H.Biographical Notes Archived 16 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine

17. A Description of the Work of Annie Besant and C W Leadbetter Archived 19 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, by Jinarajadasa

18. Editions.

19. Tillett 1986, p. 1078.

20. Britannica2.

21. Shepard 1991.

22. Melton 2001c.

23. Cambridge Books.

24. Kuhn 1992, p. 113.

25. Ellwood.

26. Leadbeater 1899.

27. Monograph.

28. Leadbeater 1899, p. 152; Tillett 1986, p. 907.

29. Harris.

30. Radhakrishnan 2008, Ch. 5/1.

31. Radhakrishnan 2008, Ch. 5/16.

32. Britannica1.

33. Tillett 1986, p. 161.

34. Melton 2001a.

35. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 131–32; Tillett 1986, pp. 161–62.

36. Leadbeater 1930, p. 133; Tillett 1986, p. 162.

37. Motoyama 2003, p. 190.

38. Eliade 1958, p. 246.

39. Hammer 2003, p. 184.

40. Leadbeater 1899, p. 42.

41. Tillett 1986, p. 220.

42. Tillett 1986, p. 221.

43. Leadbeater 1899, p. 106; Tillett 1986, pp. 197–98.

44. WorldCat.

45. Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934 – A Biographical Study, Gregory John Tillett, First Edition: University of Sydney, Department of Religious Studies, March 1986, 2008 Online Edition published at [Leadbeater.Org], chpt 10, p. 247.

46. Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934 – A Biographical Study, Gregory John Tillett, First Edition: University of Sydney, Department of Religious Studies, March 1986, 2008 Online Edition published at [Leadbeater.Org], chpt 11, p. 395.

47. Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934 – A Biographical Study, Gregory John Tillett, First Edition: University of Sydney, Department of Religious Studies, March 1986, 2008 Online Edition published at [Leadbeater.Org], chpt 11, pg 398

48. Lutyens 1975 pp. 20–21.

49. Lutyens 1975 pp. 11–12.

50. Lutyens 1975 pp. 23–24.

51. Lutyens 1975 "Chapter 33: Truth is a Pathless Land", pp. 272–275.

52. Lutyens 1975 pp. 276–278, 285.

53. Tillet, 1986, "supra"

54. Lutyens 1975 p. 191.

55. Tillet, 1982, "supra".

56. The Theosophist, August 1997, pp. 460–463.

57. The Liturgy according to the Use of the Liberal Catholic Church (Preface), p. 11.

58. The Liturgy according to the Use of the Liberal Catholic Church (Preface), p. 249.

59. The Science of the Sacraments, New 2007 edition (Preface by John Kersey), p. 11.

60. Formats and editions.

61. Leadbeater 1967, p. 8; Tillett 1986, pp. 99–100.

62. Leadbeater 1967, pp. 10–11; Tillett 1986, p. 101.

63. Leadbeater 1967, pp. 11–12; Tillett 1986, p. 102.

64. Melton 2001b.

65. Leadbeater 1967, p. 12; Tillett 1986, p. 102.

66. Tillett 1986, p. 107.

67. Melton 2001.

68. Matley 2013.

69. Leadbeater 1930, Ch. II.

70. Tillett 1986, pp. 112–13, 122.

71. Leadbeater 1930, p. 22; Tillett 1986, pp. 122–23.

72. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 24–5; Tillett 1986, pp. 124–25.

73. Сенкевич 2012, pp. 404–5.

74. Tillett 1986, p. 970.

75. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 43–4; Tillett 1986, pp. 131–32.

76. Leadbeater 1930, p. 50; Tillett 1986, p. 133.

77. Leadbeater 1930, Ch. IV.

78. Oliveira.

79. Tillett 1986, p. 126.

80. Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 6.

81. Tillett 1986, p. 966.

82. Tillett 1986, pp. 126–27.

83. Leadbeater 1930, Ch. V.

84. Jinarajadasa 1919, p. 33.

85. Jinarajadasa 1919, pp. 33–5.

86. Tillett 1986, p. 138.

87. Jinarajadasa 2013, First phenomenon.

88. Jinarajadasa 1919, p. 113.

89. Jinarajadasa 1919, p. 35; Tillett 1986, p. 139.

90. Leadbeater 1930, p. 62; Washington 1995, p. 117.

91. Leadbeater 1930, p. 91; Tillett 1986, pp. 144–45.

92. Leadbeater 1930, p. 92; Tillett 1986, p. 145.

93. Сенкевич 2012, p. 414.

94. Leadbeater 1930, p. 101; Tillett 1986, p. 147.

95. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 103–6; Tillett 1986, p. 148.

96. Leadbeater 1930, p. 118; Tillett 1986, p. 150.

97. Сенкевич 2012, pp. 416–17.

98. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 130–31; Tillett 1986, pp. 160–61.

99. Leadbeater 1930, p. 149; Tillett 1986, p. 158.

100. Leadbeater 1930, p. 151; Tillett 1986, p. 155.

101. Hammer 2003, p. 185.

102. Leadbeater 1930, p. 133; Tillett 1986, p. 162; Wessinger 2013, p. 36.

103. Leadbeater 1930, pp. 133–34; Tillett 1986, p. 163.

104. Leadbeater 1930, p. 134; Tillett 1986, p. 165.

https://diedrei.org/tl_files/hefte/2015 ... D_1509.pdf letter of J. Krishnamurti´s father to Rudolf Steiner dated 12.3.1912 talking about his efforts to avoid his sons having any future contact to Leadbeater

Sources• "Abhijna". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• "Clairvoyance". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• "Formats and Editions of Clairvoyance". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• "Formats and editions of How theosophy came to me". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• "Clairvoyance (monograph)". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• "Clairvoyance by Charles Webster Leadbeater". Cambridge Books Online. Cambridge University Press. 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• "Leadbeater, Charles Webster 1854–1934". WorldCat Identities. OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Melton, J. G., ed. (2001c). "Clairvoyance". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 1 (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 297–301. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Melton, J. G., ed. (2001). "Husk, Cecil (1847–1920)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 1 (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 757–58. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Melton, J. G., ed. (2001a). "Kundalini". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 1 (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 881–83. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Melton, J. G., ed. (2001b). "Levitation". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 1 (5th ed.). Gale Group. pp. 909–18. ISBN 0-8103-8570-8. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Shepard, L., ed. (1991). "Clairvoyance". Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. 1 (3rd ed.). Detroit: Gale Research Inc. pp. 292–94. ISBN 0810349159. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Eliade, M. (1958). Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Translated by Trask, W. R. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691017648. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Ellwood, R. S. (15 March 2012). "Leadbeater, Charles Webster". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Goodrick-Clarke, N. (2004). Helena Blavatsky. Western esoteric masters. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-55643-457-X. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Hammer, O. (2003). Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Studies in the history of religions. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004136380. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Harris, P. S. (5 December 2011). "Clairvoyance". Theosopedia. Manila: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Jinarajadasa, C., ed. (1919). Letters from the masters of the wisdom, 1881–1888. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. OCLC 5151989.

• Jinarajadasa, C. (2013) [1941]. The K. H. Letters to C. W. Leadbeater. Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 9781258882549. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Kuhn, A. B. (1992) [1930]. Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom (PhD thesis). American religion series: Studies in religion and culture. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-175-3.

• Leadbeater, C. W. (1899). Clairvoyance. London: Theosophical Publishing Society. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Leadbeater, C. W. (1930). How Theosophy Came to Me. Adyar: Theosophical Pub. House. OCLC 561055008. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• ———— (1967) [1930]. How Theosophy Came to Me (3rd ed.). Madras: Theosophical Pub. House. OCLC 221982801. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Matley, J. W. (2013) [1941]. "C. W. Leadbeater at Bramshott Parish". The K. H. Letters to C. W. Leadbeater. Literary Licensing, LLC. pp. 105–108. ISBN 9781258882549. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Motoyama, H. (2003) [1981]. Theories of the Chakras: Bridge to Higher Consciousness (Reprint ed.). New Age Books. ISBN 9788178220239. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

• Oliveira, P. "With Madame Blavatsky". CWL World. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Radhakrishnan, S. (2008). Indian Philosophy. 2 (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195698428.

• Tillett, Gregory J. (1986). Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934: a biographical study (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of Sydney (published 2007). OCLC 220306221. Retrieved 16 June 2018 – via Sydney Digital Theses.

• Washington, P. (1995). Madame Blavatsky's baboon: a history of the mystics, mediums, and misfits who brought spiritualism to America. Schocken Books. ISBN 9780805241259. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

• Wessinger, C. (2013). "The Second Generation Leaders of the Theosophical Society (Adyar)". In Hammer, O.; Rothstein, M. (eds.). Handbook of the Theosophical Current. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Boston: Brill. pp. 33–50. ISBN 9789004235960. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

• Сенкевич, А. Н. (2012). Елена Блаватская. Между светом и тьмой [Helena Blavatsky. Between Light and Darkness]. Носители тайных знаний (in Russian). Москва: Алгоритм. ISBN 978-5-4438-0237-4. OCLC 852503157. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

Further reading• Caldwell, Daniel. Charles Webster Leadbeater: His Life, Writings & Theosophical Teachings.

• Kersey, John. Arnold Harris Matthew and the Old Catholic Movement in England: 1908–52

• Kersey, John. The Science of the Sacraments by Charles Webster Leadbeater. New 2007 Edition with a Preface by John Kersey

• Michel, Peter. Charles W. Leadbeater:Mit den Augen des Geistes ISBN 3-89427-107-8 (In German; No English translation available)

• Tillett, Gregory. The Elder Brother: A Biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater.

• Lutyens, Mary. Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening; Avon Books (Discus), New York. 1983 ISBN 0-380-00734-7

• Oliveira, Pedro. CWL Speaks: C.W. Leadbeater's Correspondence concerning the 1906 Crisis in the Theosophical Society Foreword by Robert Ellwood ISBN 978-0-646-97305-0

External links• How Theosophy Came to Me

• Works by Charles Webster Leadbeater at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Charles Webster Leadbeater at Internet Archive

• Works by Charles Webster Leadbeater at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• A chronological listing of C.W. Leadbeater's books and pamphlets

• C.W. Leadbeater life, writings and theosophical teachings at the Blavatsky Study Center

• Articles by and about C.W. Leadbeater

• C.W. Leadbeater articles and media

• Leadbeater in Sydney: Garry Wotherspoon (2011). "Leadbeater, Charles". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]