Behold the Green Dragon: The Myth & Reality of an Asian Secret Society

by Richard Spence

New Dawn Magazine

Jan-Feb 2009

History certainly has no shortage of enigmatic or controversial brotherhoods, orders, lodges and societies. The Knights Templar, for instance, are a perennial object of fascination and speculation. Whether the Templars were the inspiration for the no less controversial Freemasons, a band of depraved heretics or the innocent victims of a conspiracy born of greed and envy remains a topic of lively debate.

What no one can contest, however, is that the Knights existed. The beginning and formal end of the Order can be dated with precision, and the names of its leaders are a matter of historical record. Even a dubious organisation like the Priory of Sion can be shown to have had a genuine, if recent, existence, though its claims to centuries of tradition and hidden influence remain unsubstantiated. But there are other groups which seem to exist only in that gray zone between reality and imagination, ones whose origins, number, scope and purpose remain maddeningly vague.

One such entity is the quasi-mythical Green Dragon Society (GDS), also known as the Order of the Green Dragon or simply the Green Dragon. It most often is mentioned as a Japanese secret society, but that is not necessarily the whole story. Other evidence, or at least allegation, argues that its true origins lay in China or Tibet and that its influence extended to the power centres of Tsarist Russia and Nazi Germany. Historical figures from the Emperor Hirohito, to Adolf Hitler to Rasputin have been tied to the Green Dragon, legitimately or not. The waters have been further muddied by role-playing games which have combined the Society with H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos and other fictional elements. Determining what is “real” and what is the playful figment of someone’s imagination can be tricky.

What follows will not solve the mystery of the Green Dragon, but it will try to separate fact from fiction and explain where claims and information came from. In doing so, it will offer a tantalising glimpse into a mysterious organisation that may have played a significant role in shaping modern history.

Enter the Black Dragon

The simplest explanation for the Green Dragon Society is that it is a muddled reference to the better known, and definitely real, Black Dragon Society (BDS) or Kokuryukai. The BDS first appeared about 1901 and was an offshoot of another, older Japanese secret society, the Black Ocean or Genyosha. Like its parent, the Black Dragon was a militant, “ultra-nationalist” body which worked to expand Imperial Japan’s influence on the Asian mainland. The BDS initially concentrated on combating Russian interests in the vast Chinese province of Manchuria. Indeed, the Society took its name from the “Black Dragon” or Amur River which separated Manchuria and Siberia. The Black Dragon’s network of spies and saboteurs took an active part in the subsequent Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) and the Black Dragons later expanded their operations and influence throughout Asia and Europe and even the Americas.

The nominal founder and leader of the Black Dragon was Ryohei Uchida, but the true master, or “darkside emperor,” was Uchida’s shadowy and sinister mentor, Mitsuru Toyama, also a founding member of Genyosha. He reputedly was steeped in “extreme Eastern religious beliefs.”1 That suggests the mysticism and occultism attributed the Green Dragon Society. Might the scheming and secretive Toyama have played a guiding role in both societies?

Were the Black and Green Dragons, if not one and the same, two sides of the same conspiratorial coin? For instance, just as the Black Dragon (Amur) River delineated the northern limit of Manchuria, further south the much smaller Qinglong or Green Dragon River roughly followed the dividing line between Manchuria and China proper. If the Black Dragon Society was primarily anti-Russian in its focus, might the Green Dragon have been anti-Chinese or anti-Western? While the Black Dragon focused on the political side, did the Green deal with the more secretive occult realm?

One obscure but important reference which clearly distinguishes between the Black and Green societies appears in the memoir of Chinese strongman Chiang Kai-shek’s “second wife,” Ch’en Chieh-ju.2 She recalls that her husband contemplated a “completely secret system of private investigators” and considered as models the “Green and Black Dragon Societies of Japan and the Triad societies of Shanghai.”3 Thus, in Chiang’s mind at least, the two Dragons were entirely separate (though not necessarily unrelated), Japanese, and appropriate models for secret intelligence gathering.

As noted, the Black Dragon Society was heavily involved in spying and the kindred spheres of propaganda and subversion. As such, it basically functioned as an extension of the Imperial Army’s “special organ,” the Tokumu Kikan. Not to be outdone in anything, the Japanese Imperial Navy maintained its own secret service, the Joho Kyoko. Just as the Army utilised the Black Dragon to augment or handle its “special needs,” might the Navy have used the Green Dragon in the same way?

Trevor Ravenscroft & Karl Haushofer

The identification of the Green Dragon as a fundamentally mystical order most evidently appears in Trevor Ravenscroft’s 1973 The Spear of Destiny. It is not insignificant that Ravenscroft was a follower of Anthroposophy and its founder Rudolf Steiner, and his book is a distinctly Anthroposophist take on the nefarious occult forces behind Hitler and his Nazi Regime. Ravenscroft firmly connects the Green Dragon to German geo-politician and mystic Karl Haushofer, one of Hitler’s presumed spiritual mentors. According to Ravenscroft, Professor Haushofer “gained… extraordinary gifts through membership of the Green Dragon Society of Japan in which the mastery of the Time Organism and the control of the life forces in the human body is the central aim of ascending degrees of initiation.” Ravenscroft adds that “one of the highest tests of this type of initiation in the Green Dragon Society demands the capacity to control and direct the life force in plants in a somewhat similar manner to the former powers of the Atlantean people.” “Only two other Europeans have been permitted to join this Japanese Order,” [and who, one wonders, were they?] continues Ravenscroft, “which demands oaths of secrecy and obedience of far more strict and uncompromising nature than similar secret societies in the Western world.”4

The major problem with all this is that Ravenscroft’s sources are hazy or non-existent. He likely took a cue from the 1960 work of Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians. Those authors claim that Haushofer “is said [by whom?] to have been initiated into one of the most important secret Buddhist societies and to have been sworn, if he failed in his ‘mission,’ to commit suicide in accordance with the time-honoured ceremonial.”5 Assuming this to be an allusion to the above GDS, we are still faced with the lack of any identifiable source for the authors’ information.

Ravenscroft goes on the claim that members of the Green Dragon Society set-up shop in 1920s Germany and there joined forces with a group of Tibetan monks called the “Society of Green Men.” The latter were, in fact, the “Adepts of Agharti and Schamballah” and their leader was a mysterious “Man with the Green Gloves.”6 It also turns out that the Green Dragons and the Green Men had “been in astral communication for hundreds of years.”7 The united brethren soon established communication with the rising Herr Hitler.

Others have since elaborated on the above by turning the Green Dragons into an “inner cabal” of both Genyosha and the Black Dragon, and making them “but an outpost of a much larger conspiracy based on the even more secretive group known and the Green Men.”8 While fascinating, such assertions appear not to have any basis in hard fact.

But that is not to say they may not have a germ of truth. For instance, there was an occult figure in late Weimar Berlin sometimes referred to as the “Magician with the Green Gloves” who did become a short-lived soothsayer for Hitler and the Nazi Party. He was no Tibetan but, of all things, a Jew who went under the name of Erik Jan Hanussen. When he became inconvenient by accurately predicting the Reichstag Fire (or arranging it), his erstwhile Nazi pals killed him.9

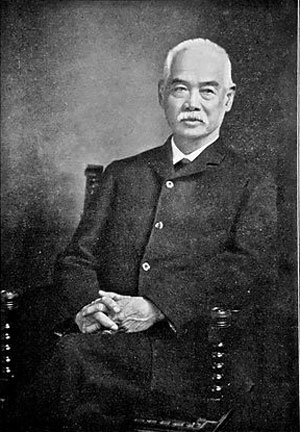

Likewise, there could very well be something to a Green Dragon-Tibet connection. A green dragon, or Zhug, plays an important role in Tibetan mythology where it symbolises the “God of Thunder… bravery and all-conquering force.”10 More to the point, perhaps, a Japanese Buddhist monk named Ekai Kawaguchi made two visits to Tibet in the years before World War I, around the same time Haushofer was in Tokyo. On the surface, Kawaguchi seemed a simple religious devotee, but he is known to have had contact with at least one Japanese secret agent while in the Land of Eternal Snows, Narita Yasuteru, as well as an operative of British Indian intelligence.11

2502, Hyer, P. 1979. Narita Yasuteru: first Japanese to enter Tibet. Tibet J. 4(3): 12-19. Narita arrived in Lhasa via India a few months after Kawaguchi, and spent two weeks there. Whilst Kawaguchi's interest in Tibet was religious, Narita's visit was at the request, and with the assistance of, the Japanese Foreign Ministry. His mission was possibly due to Japanese concern about Russian activity in Inner Asia and their need for information on the Tibetan situation. Also includes information on correspondence between Narita and Sarat Chandra Das concerning Kawaguchi's published account of his time in Tibet.

-- Britain and Tibet 1765-1947: A Select Annotated Bibliography of British relations with Tibet and the Himalayan states including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan, by Julie G. Marshall

There are many cheap inns and hotels in Lhasa, but as I had been informed that they were not respectable, I desired to stay with a friend, a son of the premier of Tibet. While at Darjeeling I had become acquainted with this young noble, and he had offered me a lodging during my stay in Lhasa. I liked him, and did many things for him, and now, though I did not mean to demand a return for what I had done for him, I had no alternative but to go to him. So I called at his house. It was known as Bandesha—a magnificent mansion on a plot of about three hundred and sixty feet square. I entered the house and asked if he was in, but heard that my friend had become a lunatic. They told me that he had gone out of his mind two years before, and that he went mad at regular periods. I learned that he was staying at his brother’s villa at Namsailing, and was obliged to go there for him, but there also I could not find him, and was told the same thing. I waited there for over two hours, as I was told he might come, and then I reflected that it would be of no use for me to see a madman, on whom I could not depend, so I made up my mind to direct my steps to the Sera monastery, for I thought it would be better for me to be temporarily admitted in the college, and then to pass the regular entrance examinations.....

Once while standing at the door of the druggist's, I saw a man apparently of quality come towards me with his servant. The store stands at the corner where the streets leading to Panang-sho and Kache-hakhang meet, and this man came along Ani-sakan street toward Panang-sho. He passed a few steps by me, when he turned and looked at me. Then I heard his servant say that I must be the man. Walking to me the nobleman said “Is it you?” I looked at him and found him, though much thinner than before, to be the son of Para the Premier, whom I had met at Darjeeling. He did not look like a man out of his senses, as I had been told. He said that he was much pleased that I had come to his country. He was on some important business, but went with me into the house of the druggist. The wife of the druggist, who knew him, gave him a chair, and the young noble seemed to be desirous to talk with me. I hinted that it was not good for us to let it be known that we had seen each other at Darjeeling, and began our talk by saying that it was about half a year since we had met each other at Gyangtze. He also was aware that his staying at Darjeeling should be kept a secret, and carefully avoided talking about our having met in that town.

From what he said and did there, I could not find anything in him that showed him to be an idiot; on the contrary, he was evidently a man of much sense. Among other things he told me that three months before, one of his servants committed theft and, when reproved severely, had pierced him through the side with a sword with the result that a part of his intestines could be seen. This, he added, made him so haggard. When, after a long talk, he went on his way, the wife of the druggist told me that the young man had hoodwinked me about the wounds, which really were given him for wrong-doing on his side. She told me that everything concerning his family was known to her, for she had before been wife to his brother, who, not being allowed to live long with her, simply because she was of birth too humble for his family, divorced her and was now adopted at Namsailing. The young man, she told me, was very prodigal, and deeply in debt, on account of which he was wounded. To my question whether he was then beside himself, she answered that he was mad or otherwise as it suited him, and not a man to be easily trusted, for he was very good at taking money from others.....

I have spoken before of the prodigal son of the house of Para. One day this man sent his servant to me with a letter and asked for a loan of money, rather a large sum for Tibet. Of course he had no idea of repaying me, and his loan was really blackmail. I sent back the servant with half of what he had asked, together with a letter. I was told that he was highly enraged at what I had done, exclaiming that I had insulted him, and that he had not asked for the sum for charity, and so on. At any rate he sent back the money to me, probably expecting that I would then send him the whole sum asked for. But I did not oblige him as he had expected, and took no notice of his threat. A few days after another letter reached me from that young man, again asking for the sum as at first. I decided to save myself from further annoyance and so I sent the sum. Like master, like servant; the latter, having heard most probably from his spendthrift master that I was a Japanese, came to me for a loan or blackmail of fifty yen. I gave that sum too, for I knew that they could not annoy me repeatedly with impunity....

Some while later on during the same day I had another startling story told me by the wife of the apothecary. She began with: “Say, Kusho-la (your lordship). Don’t you think the most awful thing in the world is a madman?”

I asked her reason, and she said: “Why, that mad son of Para has been telling a strange story. It is a story told by a madman, so of course I think it cannot be depended upon; but he said that though it was a great secret, he knew of a horrible affair that was to take place in this country. When I asked what it was, he whispered to me: ‘There is a priest from Japan in this town. He calls himself a priest, but he is surely a great officer of the Japanese Government, who has been sent for the investigation of the country. It is no less a personage than the Serai Amchi [Ekai Kawaguchi]. I met and talked with him once when I went to Darjeeling, and I found him a great man.’ This is what he tells me. Is it not strange? Nobody knows he has ever been to Darjeeling, but what do you think about it?”

I thought the madman was not mad if he had spoken that way, but answered her: “The story of a madman must be only taken as such.”

The lady continued, “Anyhow my husband and many others seem to believe it. I have told this to you as I heard it, and hope you will not mind.”

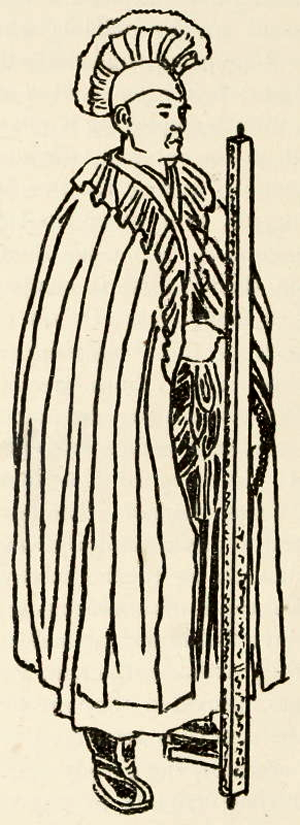

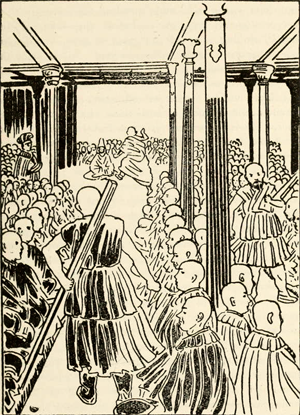

-- Three Years in Tibet, with the original Japanese illustrations, by Shramana Ekai Kawaguchi, Late Rector of Gohyakurakan Monastery, Japan

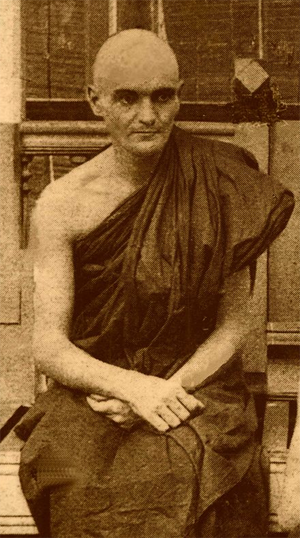

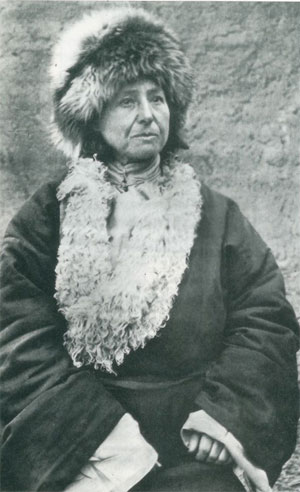

Kawaguchi also had links to Annie Besant and her Theosophist sect, another group accused of subversion and general skullduggery.12 More significantly, Kawaguchi was a devotee of Zen Buddhism.

CHAPTER LXXI. Russia’s Tibetan Policy.

Before proceeding to give an account, necessarily imperfect, of Tibetan diplomacy, I must explain what is the public opinion of the country as to patriotism. I am sorry to say that the attitude of the people in this respect by no means does them credit. So far as my limited observation goes, the Tibetans, who are sufficiently shrewd in attending to their own interest, are not so sensitive to matters of national importance. It seems as if they were destitute of the sense of patriotism, as the term is understood by ordinary people. Not that they are totally ignorant of the meaning of “fatherland,” but they are rather inclined to turn that meaning to their own advantage in preference to the interest of their country. Such seems, in short, the general idea of the politicians of to-day.

The Tibetans are more jealous with regard to their religion. A few of them, a very limited few it is true, seem to be prepared to defend and promote it at the expense of their private interest, though even in this respect the majority are so far unscrupulous as to abuse their religion for their own ends. In the eyes of the common people, religion is the most important product of the country, and they think therefore that they must preserve it at any cost. Their ignorance necessarily makes them fanatics and they believe that any one who works any injury to their religion deserves death. The Hierarchical Government makes a great deal of capital out of this fanatical tendency of the masses. The holy religion is its justification when it persecutes persons obnoxious to it, and when it has committed any wrong it seeks refuge under the same holy name. The Government too often works mischief in the name of religion, but the masses do not of course suspect any such thing—or even if they do now and then harbor a suspicion, they are deterred from giving vent to their sentiments, for to speak ill of the religion is a heinous crime in Tibet....

A foreign country knowing this weak point, and wishing to push its interests in the Forbidden Land, has only to form its diplomatic procedure accordingly. In other words, it has merely to captivate the hearts of the rulers of Tibet, for once the influential Cabinet Ministers of the Hierarchical Government are won over, the next step will be an easy matter. The greedy Ministers will be ready to listen to any insidious advice coming from outside, provided that the advice carries with it literally the proper weight of gold. They will not care a straw about the welfare of the State or the interest of the general public, if only they themselves are satisfied.

However, foreign diplomatists desiring to succeed in their policy of gaining influence over Tibet must not think that they have an easy task before them. Gold is most acceptable to all Tibetan statesmen, but at times gold alone may not carry the point. The fact is that Tibet has no diplomatic policy in any dignified sense of the word. Its foreign doings are determined by sentiment, which is necessarily destitute of any solid foundation, but is susceptible to change from a trivial cause.... It is impossible to rely on the faith of the Tibetan statesmen, for they are entirely led by sentiment and never by rational conviction....

There was a Mongolian tribe called the Buriats, which peopled a district far away to the north-east of Tibet towards Mongolia. The tribe was originally feudatory to China, but it passed some time ago under the control of Russia. The astute Muscovites have taken great pains to insinuate themselves into the grateful regard of this tribe. Contrary to their vaunted policy at home, they have never attempted to convert the Mongolians into believers of the Greek Church, but have treated their religion with a strange toleration. The Muscovites even went farther and actually rendered help in promoting the interests of the Lamaist faith, by granting its monasteries more or less pecuniary aid.... From this tribe quite a large number of young priests are sent to Tibet to prosecute their studies at the principal seats of Lamaist learning. These young Mongolians are found at the religious centres of Ganden, Rebon, Sera, Tashi Lhunpo and at other places. There must be altogether two hundred such students at those seats of learning; several able priests have appeared from among them, one of whom, Dorje by name, became a high tutor to the present Dalai Lama while he was a minor....

The Tsan-ni Kenbo returned home when, on his pupil’s attaining majority, his services as tutor were no longer required. It is quite likely that he described minutely the results of his work in Tibet to the Russian Government, for it is conceivable that he may have been entrusted by it with some important business during his stay at Lhasa. Soon the Tsan-ni Kenbo re-visited Lhasa, and this time as a priest of great wealth, instead of as a poor student, as he was at first. He brought with him a large amount of gold, also boxes of curios made in Russia. The money and the curios must have come to him from the Russian Government. The Dalai Lama and his Ministers were the recipients of the gold and curios, and among the Ministers a young man named Shata appears to have been honored with the largest share....

The Dalai Lama was now ready to lend a willing ear to anything his former tutor represented to him, while the friendship between him and the young Premier grew so fraternal that they are said to have vowed to stand by each other as brothers born. The astute Tsan-ni did not of course confine his crafty endeavors to the higher circles alone; the priest classes received from him a large share of attention, due to the mighty influence which they wield over the masses. Liberal donations were therefore more than once presented to all the important monasteries of Tibet, with which of course the priests of these monasteries were delighted. In their eyes the Tsan-ni was a Mongolian priest of immense wealth and pious heart, and the idea of suspecting how he came to be possessed of such wealth never entered their unsophisticated minds....

It must be remembered that a work written in former times by some Lama of the New Sect contained a prophetic pronouncement—a pronouncement which was supported by some others—that some centuries hence a mighty prince would make his appearance somewhere to the north of Kashmīr, and would bring the whole world under his sway, and under the domination of the Buḍḍhist faith.....

This announcement alone was not sufficiently attractive to awake the interest of the Tibetans, and so the unborn prince was represented as a holy incarnation of the founder of the national religion of Tibet, Tsong-kha-pa, and his Ministers were to be incarnations of his principal disciples, as Jam yan Choeje, Chamba Choeje and Gendun Tub. The prophet went into further details and gave the name of the future great country as “Chang Shambhala”... With a precision worthy of Swift’s pen, the prophet located the new Buḍḍhist empire of the future at a distance some three thousand miles north-west of Buḍḍhagayā in Hinḍūsṭān, and he even described at some length the route to be taken in reaching the imaginary country. This utopian account has obtained belief from a section of the Tibetan priest-class, and some of them are said to have undertaken a quest for this future empire, so that they might at least have the satisfaction of inspecting its cradle. Now the Tibetan prophet bequeathed us this important forecast with the idea that when the Tibetan religion degenerated, it would be saved from extinction by the appearance of that mighty Buḍḍhist prince, who would extend his benevolent influence over the whole world. I should state that this announcement is widely accepted as truth by the common people of Tibet.

The Tsan-ni Kenbo was perfectly familiar with the existence of this marvellous tradition, and he was not slow to utilise it for promoting his own ambitious schemes. He wrote a pamphlet with the special object of demonstrating that “Chang Shambhala” means Russia, and that the Tsar is the incarnation of Je Tsong-kha-pa. The Tsar, this Russian emissary wrote, is a worthy reincarnation of that venerable founder, being benevolent to his people, courteous in his relations to neighboring countries, and above all endowed with a virtuous mind. This fact and the existence of several points of coincidence between Russia and the country indicated in the sacred prophecy indisputably proved that Russia must be that country, that anybody who doubted it was an enemy of Buḍḍhism and of the august will of the Founder of the New Sect, and that in short all the faithful believers in Buḍḍhism must pay respect to the Tsar as a Chang-chub Semba Semba Chenbo, which in Tibetan indicates one next to Buḍḍha, or as a new embodiment of the Founder, and must obey him....

Tsan-ni Kenbo’s artful scheme has been crowned with great success, for to-day almost every Tibetan blindly believes in the ingenious story concocted by the Mongolian priest, and holds that the Tsar will sooner or later subdue the whole world and found a gigantic Buḍḍhist empire. So the Tibetans may be regarded as extreme Russophiles, thanks to the machination of the Tsan-ni Kenbo.

There is another minor reason which has very much raised the credit of Russia in the eyes of the Tibetans; I mean the arrival of costly fancy goods from that country.... The ignorant Tibetans do not of course exercise any great discernment, and seeing that the goods from England and Russia make such a striking contrast with each other they naturally jump to the conclusion that the English goods are trash, and that the people who produce such things must be an inferior and unreliable race.

I heard during my stay in Tibet a strange story the authenticity of which admitted of no doubt. It was kept as a great secret and occurred about two years ago. At that time the Dalai Lama received as a present a suit of Episcopal robes from the Tsar, a present forwarded through the hands of the Tsar’s emissary. It was a splendid garment glittering with gold and was accepted, I was told, with gratitude by the Grand Lama....

Shata, whose name I have before mentioned, is the eldest of the Premiers, and comes from one of the most illustrious families of Tibet. His house stood in hereditary feud with the great monastery Tangye-ling whose head, Lama Temo Rinpoche, acted as Regent before the present Dalai Lama had been installed. At that time the star of Shata was in the decline. He could not even live in Tibet with safety, and had to leave the country as a voluntary exile. As a wanderer he lived sometimes at Darjeeling and at other times in Sikkim. It was during this period of his wandering existence that he observed the administration of India by England, and heard much about how India came to be subjugated by that Power. Shata therefore is the best authority in Tibet about England’s Indian policy. His mind was filled with the dread of England.... He must have thought during his exile that Tibet would have to choose between Russia and China in seeking foreign help against the possible aggression of England. Evidently therefore he carried home some such idea as to Tibetan policy when affairs allowed him to return home with safety, that is to say, when his enemy had resigned the Regency and surrendered the supreme power to the Dalai Lama. Shata was soon nominated a Premier, and the power he then acquired was first of all employed and abused in destroying his old enemy and his followers. The maladministration and unjust practices of which those followers had been guilty during the ascendancy of their master furnished a sufficient cause for bringing a serious charge against the latter. The poor Temo Rinpoche was arrested for a crime of which he was innocent, and died a victim to his enemy, as already told ...

China’s loss of prestige in Tibet since the Japano-Chinese war owing to her inability to assert her power over the vassal state has much to do with this pro-Russian leaning. China is no longer respected, much less feared by the Tibetans. Previous to that war and before China’s internal incompetence had been laid bare by Japan, relations like those between master and vassal bound Tibet to China. The latter interfered with the internal affairs of Tibet and meted out punishments freely to the Tibetan dignitaries and even to the Grand Lama. Now she is entirely helpless. She could not even demand explanations from Tibet when that country was thrown into an unusual agitation about the Temo Rinpoche’s affair. The Tibetans are now conducting themselves in utter disregard or even in defiance of the wishes of China, for they are aware of the powerlessness of China to take any active steps against them. They know that their former suzerain is fallen and is therefore no longer to be depended upon. They are prejudiced against England on account of her subjugation of India, and so they have naturally concluded that they should establish friendly relations with Russia, which they knew was England’s bitter foe....

The Dalai Lama’s friendly inclination was clearly established when in December, 1900, he sent to Russia his grand Chamberlain as envoy with three followers. Leaving Lhasa on that date the party first proceeded towards the Tsan-ni Kenbo’s native place, whence they were taken by the Siberian railway, and in time reached S. Petersburg. The party was received with warm welcome by that court, to which it offered presents brought from Tibet. It is said that on that occasion a secret understanding was reached between the two Governments.

It was about December of 1901 or January of the following year that the party returned home. By that time I had already been residing in Lhasa for some time. About two months after the return of the party I went out on a short trip on horseback to a place about fifty miles north-east of Lhasa. While I was there I saw two hundred camels fully loaded arrive from the north-east. The load consisted of small boxes, two packed on each camel. Every load was covered with skin, and so I could not even guess what it contained. The smallness of the boxes however arrested my attention, and I came to the conclusion that some Mongolians must have been bringing ingots of silver as a present to the Dalai Lama. I asked some of the drivers about the contents of the boxes, but they could not tell me anything. They were hired at some intermediate station, and so knew nothing about the contents. However they believed that the boxes contained silver, but they knew for certain that these boxes did not come from China....

When I returned to the house of my host, the Minister of Finance came in and informed him that on that day a heavy load had arrived from Russia. On my host inquiring what were the contents of the load, the Minister replied that this was a secret....

Now I knew one Government officer who was one of the worst repositories imaginable for any secret; he was such a gossip that it was easy to worm out anything from him.... he told me (confidentially, he said) that another caravan of three hundred camels had arrived some time before, and that the load brought by so many camels consisted of small fire-arms, bullets, and other interesting objects. He was quite elated with the weapons, saying that now for the first time Tibet was sufficiently armed to resist any attack which England might undertake against her, and could defiantly reject any improper request which that aggressive power, as the Tibetans believe her to be, might make to her.

I had the opportunity to inspect one of the guns sent by Russia. It was apparently one of modern pattern, but it did not impress me as possessing any long range nor seem to be quite fit for active service. The stock bore an inscription attesting that it was made in the United States of America. The Tibetans being ignorant of Roman letters and English firmly believed that all the weapons were made in Russia. It seems that about one-half of the load of the five hundred camels consisted of small arms and ammunition.

The Chinese Government appears mortified to see Tibet endeavoring to break off her traditional relation with China, and to attach herself to Russia. The Chinese Amban once tried to interfere with the Tsan-ni Kenbo’s dealings in Lhasa, and even intended to arrest him. But it was of no avail, as the Tibetan Government extended protection to the man and defeated the purposes of the Amban. On one occasion the Tsan-ni was secretly sent to Darjeeling and on another occasion to Nepāl, and the Amban could never catch hold of him. It appears that the British Government watched the movements of the Tsan-ni, and this suspicion of England against him appears to have been shared by the Nepāl Government.

Apparently therefore the Russian manœuvres in Tibet have succeeded, and the question that naturally arises is this: “Is Russia’s footing in Tibet so firmly established as to enable her to make with any hope of success an attempt on India with Tibet as her base?” I cannot answer this question affirmatively, for Russia’s influence in Tibet has not yet taken a deep root. She can count only on the Dalai Lama and his Senior Premier as her most reliable friends, and the support of the rest who are simply blind followers of those two cannot be counted upon. Of course those blind followers would remain pro-Russian, if Russia should persist in actively pushing on her policy of fascination; but as their attitude does not rest on a solid foundation they may abandon it any time when affairs take a turn unfavorable for Russia....

***

CHAPTER LXXII. Tibet and British India.

The Tibetans are on the whole a hospitable people, and the unfavorable discrimination made against England is mainly attributable to mutual misunderstanding. On the part of England that misunderstanding led to the adoption of a rough and ready method instead of one of ingratiation, and so England is singled out as an object of abhorrence by Tibet. England had opportunities to score a greater success in Tibet than that achieved by Russia, and had she followed the Russian method her influence would now have extended far beyond the Himālayas. Instead, she tried to coerce Tibet, and so she failed. It is like crying over spilt milk to speak of this failure at present, but I cannot help regretting it for the sake of England. She would have saved much of the trouble and money she has subsequently been obliged to give in consequence of her too hasty policy, occasioned by her ignorance of the temper of the Tibetans and the general state of affairs in their country. As it was, since England sent her abortive expedition of force, the attitude of Tibet towards that Power has become one of pronounced hostility. The revelation of the secret mission of Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās and the serious agitation that occurred in Tibet, including the execution of several noted men, such as the virtuous Sengchen Dorjechan and others, has completely estranged the Tibetan Government from England. That revelation has had a far-reaching effect that has involved the interests of other countries, for it confirmed the Tibetan Government in its prejudice in favor of a exclusory policy. Tibet has been closed up entirely since that time, not only against British India, but even against Russia and Persia. The Lama believers of India even are prohibited from entering the country. Such being the case, should England ever wish to transact any business with Tibet she would be obliged to do so by force.

Not that England neglects to take measures calculated to win the favorable opinion of the Tibetans. The Indian Viceroy is, for instance, endeavoring to convey friendly impressions to such of the Tibetans as may happen to come to frontier places, such as Darjeeling or Sikkim. Thus the children of those Tibetans are at liberty to enter any Government schools without paying fees, while boys of a hopeful nature are patronised by the Government and are sent at Government expense to higher institutions. At present there are quite a number of Tibetan lads who, after graduation from their respective courses, are employed by the Indian Government as surveyors, Post Office clerks or teachers. Then the privilege of carrying on the business of palanquin-bearers, quite a lucrative occupation, is practically reserved for the Tibetans, at least at Darjeeling. Not even natives of India, still less people of other countries, are easily allowed to start this business. The Indian Police officers too are quite indulgent towards the Tibetans, and never deal with them so strictly as with the Indian natives.

The Tibetans residing at Darjeeling are therefore quite satisfied with their lot....They are impressed with the treatment of the British Government, its straightforwardness, veracity and benevolence, in contrast to the merciless dealings of the Government at home, which inflicts shocking punishments for even minor offences. They are well aware that the Lama’s Government cuts off a man’s arms or extracts his eye-balls for larceny, or similar minor crimes, while in India capital punishment is very seldom inflicted even on offenders of a grave character; the humane treatment of criminals by the British Government is a thing that can hardly be dreamed of by the people of Tibet. The roads in India are an object of marvel to the Tibetans who arrive there for the first time. The presence of free hospitals, of free asylums, of educational institutions, the railways, telegraphs and telephones—all these are objects of wonder and marvel to those Tibetans, and it is not strange that most of them become the more disinclined to return home the longer they live in India....

The policy of indirectly winning the goodwill of the Tibetans, so far pursued by the Indian Government, has failed, however, to produce any perceptible effect on the Government circles of Tibet. They are too far engrossed with personal interests to be open to any great extent to indirect suasion of a moral nature. They are far more inclined to gain advantage for themselves directly from offers of bribes than to profit by an exemplary model of administration. The main reason why they are favorably disposed towards Russia is because they have received gold from that country; it was never by the effect of any display of good administrative method that Russia has succeeded so well. In short, these greedy Tibetan officials offer their friendship to the highest bidders, and they do not care at all whence the gold comes so long as they grasp a large sum. The policy of the British Government therefore rests on a pedestal set a little too high to be understood and appreciated by the majority of the official circles of Tibet....

The existence of the Siberian railway can hardly be expected to give any great help to Russia, if ever the latter should be obliged from one reason or another to send a warlike expedition to Lhasa. The distance from the nearest station to Lhasa is prohibitive of any such undertaking, for the march, even if nothing happens on the road, must require five or six months and is through districts abounding in deserts and hills. The presence of wild natives in Amdo and Kham is also a discouraging factor, for they are people who are perfectly uncontrollable, given up to plunder and murder, and of course thoroughly at home in their own haunts. Even discipline and superior weapons would not balance the natural advantages which these dreadful people enjoy over intruders, however well informed the latter may be about the topography of the districts. Russia can hardly expect to subdue Tibet by force of arms....

It must be remembered that the sentiment of the common people towards China still retains its old force, even though they know that the power of their old patron has considerably declined lately. They are well aware that Tibet has been placed from time immemorial in a state of vassalage to China, that Prince Srong-tsan Gambo who first introduced Buḍḍhism into Tibet had as his wife a daughter of the then Emperor of China, while the Tibetans believe that the present Emperor of China is an incarnation of a Buḍḍhist deity (the Chang-chub Semba Tambe yang in Tibetan) worshipped on Mount Utai, China. And so both from tradition and prejudice and from present superstition, the mass of the people, who are conservative, cannot but regard China with a lingering sentiment of respect and attachment, and the position which China still occupies in the niches of their hearts can hardly be supplanted by Russia, even when the Tsan-ni Kenbo ingeniously represents her as the country indicated in the Tibetan Book of Prophecy.

As I have mentioned before, some few of the influential Government officials do not seem to approve of the Tsan-ni’s movement. They even suspect that Russia might have some sinister object in view when she presented gold and other valuable things to the Dalai Lama and others. ... The result is that not a small number of priests have begun to side, though not as an organised movement, with these prudent thinkers, and therefore to rebel against Shata and his faction. The priests of the colleges and the warrior-priests seem to be particularly conspicuous in this reactionary movement.... Then again the thoughtful portion of the college-priests never tolerated the Nechung oracles. They despised the oracle-priests as not much better than men of unsound mind, as drunkards, and corrupters of national interests. The very fact that Shata patronised this vile set further estranged him from the college-priests....

In reviewing the relations that formerly existed between British India and Tibet, it must be stated first of all that British India was closely connected with Tibet many years ago. At least Tibet’s attitude toward the Indian Government was not embittered by any hostile sentiment. In the eighteenth century, during the Governor-Generalship of Warren Hastings, he sent George Bogle to make commercial arrangements between the two countries. This gentleman resided a few years at Shigatze. Then Captain Turner also lived at the same place as a commercial agent for some time.... Though official relations had ceased between Tibet and India, their people therefore were bound together by some friendly connexions till quite recently. It is not unlikely that if the Indian Government had made at that time some advances acceptable to Tibet, it would have succeeded in establishing cordial relations with the latter.

The exploration of Saraṭ Chanḍra Ḍās disguised as an ordinary Sikkimese priest, and the frontier trouble that followed it, completely changed the attitude of Tibet towards India and the outer world and made it adopt a strict policy of exclusion....

***

CHAPTER LXXIII. China, Nepal and Tibet.

It requires the erudition and investigations of experts to write with any adequacy about the earlier relations between China and Tibet. I must therefore confine myself here only to the existing state of those relations.

Tibet is nominally a protectorate of China, and as such she is bound to pay a tribute to the Suzerain State. In days gone by, Tibet used to forward this tribute to China, but subsequently the payment was commuted against expenses which China had to allow Tibet, on account of the Grand Prayer which is performed every year at Lhasa for the prosperity of the Chinese Emperor. As a result of this arrangement, Tibet ceased to send the tribute and China to send the prayer fund.

The loss of Chinese prestige in Tibet has been truly extraordinary since the Japano-Chinese War. Previous to that disastrous event, China used to treat Tibet in a high-handed way, while the latter, overawed by the display of force of the Suzerain, tamely submitted. All is now changed, and instead of that subservient attitude Tibet regards China with scorn. The Tibetans have come to the conclusion that their masters are no longer able to protect and help them, and therefore do not deserve to be feared and respected any more. It can easily be understood how the Chinese are mortified at this sudden downfall of their prestige in Tibet. They have tried to recover their old position, but all their endeavors have as yet been of no avail. The Tibetans listen to Chinese advice when it is acceptable, but any order that is distasteful to them is utterly disregarded....

In Nepāl the military department receives appropriations which are quite out of proportion to those set apart for peaceful matters, as education, justice and philanthropy. Indeed the Nepāl troops, the famous Gurkhas, may even rival regular British troops in discipline and effectiveness; they may perhaps even surpass the others in mountain warfare, such as would take place in their own country. Certainly in their capacity of enduring hardships and in running up and down hills, bearing heavy knapsacks, they are superior to the British soldiers. They very much resemble the Japanese soldiers in stature and general appearance, and also in temperament. The one might easily be mistaken for the other, so close is the resemblance between the two. In short, as fighters in mountainous places the Gurkhas form ideal soldiers; and it seems as though circumstances will sooner or later compel Nepāl to employ for her self-defence this highly effective force. Russia is at the bottom of the impending trouble, while Tibet supplies the immediate cause.

The Russianising tendency of Tibet has recently put Nepāl on her guard, and when intelligence reached Nepāl that Tibet had concluded a secret treaty with Russia, that the Dalai Lama had received a bishop’s robe from the Tsar, and that a large quantity of arms and ammunition had reached Lhasa from S. Petersburg, Nepāl became considerably alarmed, and with good reason. For with Russia established in Tibet, Nepāl must necessarily feel uneasy, as it would be exposed to the danger of absorption. The very presence of a powerful neighbor must subject Nepāl to a great strain which can hardly be borne for long.

It is not surprising to hear that Nepāl is said to have communicated in an informal manner with Tibet and to have demanded an explanation of the rumors concerning the conclusion of a secret treaty between her and Russia, adding that if that were really the case then Nepāl, from considerations of self-defence, must oppose that arrangement even if the opposition entailed an appeal to arms....

Nepāl may be driven to declare war on Tibet should the latter persist in pursuing her pro-Russian policy, and allow Russia to establish herself in that country; and it is quite likely that England may be pleased to see Nepāl adopt that resolute attitude. She may even extend a helping hand, for instance by supplying part of the war expense, and thus enabling Nepāl to prosecute that movement. The reason is obvious, for England has nothing to lose but everything to gain from trouble between Nepāl and Tibet, in which the former may certainly be expected to win. But even if Nepāl is victorious her victory will bring her only a small benefit, and the lion’s share will go to England; Nepāl therefore would be placed in the rather foolish position of having taken the chestnuts from the fire for the British lion to eat. The present Ruler of Nepāl is too intelligent a statesman not to perceive that—judging at least from my personal observations, when I was allowed to see the Ruler, the Cabinet Minister....

Thus, it is hardly likely that Nepāl will go to extreme measures towards Tibet, even if England should cleverly encourage her.

It must be remembered that the relations between the two countries are not yet strained. The Tibetans do not seem to harbor any ill-feeling towards their neighbors beyond the mountains, nor do they regard them as a whole with fear, though they do fear the Gurkhas on account of their valor and discipline. The Tibetan Government also seems to be desirous of maintaining a friendly relation with Nepāl. For instance, when on one occasion the Ruler of Nepāl sent his messenger to Tibet to procure a set of Tibetan sūṭras, the Dalai Lama, who heard of that errand, caused a set to be sent to Nepāl as a present from himself, which is now kept in the Royal Library of Nepāl.

The Nepāl Government, on its part, appears to be doing its best to create a favorable impression on the Tibetans. The Ruler, it must be remembered, is not a Buḍḍhist but a Brāhmaṇa; still, he pursues the policy of toleration towards all faiths, and is especially kindly to Buḍḍhists. The Buḍḍhists from Tibet who are staying in Nepāl enjoy protection from the Government, and the Ruler not unfrequently makes grants of money or timber when Buḍḍhist temples are to be built in his dominion. The care bestowed by the Ruler on the Buḍḍhists is highly appreciated by their friends at home, and Nepāl is therefore favorably situated for winning the hearts of the Tibetan people. It is easily conceivable that with a judicious use of secret service funds Nepāl might easily establish her influence in Tibet. This, however, cannot be readily expected from that country, as internal conditions now are, for order is far from being firmly established in that little kingdom, and domestic troubles and administrative changes occur too frequently. Even the Prime Minister, who wields the real power, has been assassinated more than once, while changes have very frequently taken place in the incumbency of that post. Nepāl is at present too deeply absorbed in her internal affairs, and cannot spare either energy or money for pursuing any consistent policy towards Tibet. Thus, though the military service of Nepāl is sufficiently creditable, her diplomacy leaves much to be desired.

***

CHAPTER LXXIV. The Future of Tibetan Diplomacy.

Tibet may be said to be menaced by three countries—England, Russia and Nepāl, for China is at present a negligible quantity as a factor in determining its future. The question is which of the three is most likely to become master of that table-land. It is evident that the three can never come to terms in regard to this question; at best England and Nepāl may combine for attaining their common object, but the combination of Russia with either of them is out of the question. Russia’s ambition in bringing Tibet under her control is too obviously at variance with the interest of the other two to admit of their coming to terms with her, for Russia’s occupation would be merely preparatory to the far greater end of making a descent on the fertile plains on the south side of the Himālayas by using Tibet as a base of operation. As circumstances stand, Nepāl has to confine her ambition to pushing her interests in Tibet by peaceful means. This is evidently the safest and most prudent plan for that country, seeing that when once that object has been attained her interest would remain unimpaired whether Tibet should fall into the hands of England or into those of Russia. After all, therefore, the future of Tibet is a problem to be solved between those two Powers. At present Russia has the ears of an important section of the ruling circles of Tibet, while on the other hand England has the mass of the Tibetan people on her side. The Russian policy, depending as it does on clever manœuvres and a free use of gold, is in danger of being upset by any sudden turn of affairs in Tibet, while the procedure of England being moderate and matter-of-fact is more lasting in its effect. Which policy is more likely to prevail cannot easily be determined, for though moderation and practical method will win in the long run, diplomacy is a ticklish affair and must take many other factors into consideration. At any rate England is warned to be on the alert, for otherwise Russia may steal a march upon her and upon Lhasa.

If the Russian troops should ever succeed in reaching Lhasa, that would open up a new era for Tibet, for the country would passively submit to the Russian rule. The Tibetans, it must be remembered, are thoroughly imbued with the spirit of negative fatalism, and the arrival of Russian troops in Lhasa would therefore be regarded as the inevitable effect of a predetermined causation, and therefore as an event that must be submitted to without resistance. The entry of those troops would never rouse the patriotic sentiment of the people. But the effect of this imaginary entry would constitute a serious menace to India. In fact, with Russia established in the natural strongholds of Tibet, India, it may be said, would be placed at the mercy of Russia, which could send her troops at any moment down to the fertile plains below. Thus would the dream of Peter the Great be realised, and of course the British supremacy on the sea would avail nothing against this overland descent across the Himālayas. Some may think that what I have stated is too extravagant, and is utterly beyond the sphere of possibility. I reply that any such thought comes from ignorance of the natural position of Tibet. Any person who has ever personally observed the immense strength which Tibet naturally commands must agree with me that its occupation by Russia would be followed sooner or later by that of India by the same aggressive power.

The question naturally arises: “Will Tibet then cease to be an independent country?” It is of course impossible to come to any positive conclusion about it, but from what I have observed and studied I cannot give a reassuring answer. The spirit of dependence on the strong is too deeply implanted in the hearts of the Tibetan people to be superseded now by the spirit of self-assertion and independence. During the long period of more than a thousand years, the Tibetan people has always maintained the idea of relying upon one or another great power, placing itself under the protection of one suzerain State or another, first India and then China. How far the Tibetans lack the manly spirit of independence may easily be judged from the following story about the Dalai Lama, who is unquestionably a man of character, gifted with energy and power of decision, who would be well qualified to lead his country to progress and prosperity did he possess modern knowledge and were he well informed of the general trend of affairs abroad. He is thoroughly familiar with the condition of his own people, and has done much towards satisfying popular wishes, redressing grievances and discouraging corrupt practices. If ever there were a man in Tibet whose heart was set on maintaining the independence of the country, it must be the Dalai Lama. So I had thought, but my fond hope was rudely shaken, and I was left in despair about the future of Tibet.

This supreme chief of the Lama Hierarchy has recently undergone a complete change in his attitude towards England. Formerly whenever England opened some negotiation with Tibet, the Dalai Lama was overcome by great perturbation, while any display of force on the part of England invariably plunged him into the deepest anxiety. He was often seen on such occasions to shut himself up in a room and, refusing food or rest, to be absorbed in painful reflexions. Now all is changed, and the same Dalai Lama regards all threats or even encroachments with indifference or even defiance. For instance, when England, chiefly to feel the attitude of Tibet and not from any object of encroachment, included, when fixing the boundary, a small piece of land that had formerly belonged to Tibet, the Dalai Lama was not at all perturbed. Instead of that he is said to have talked big and breathed defiance, saying that he would make England rue this sooner or later. His subjects, it is reported, were highly impressed on this occasion and they began to regard him as a great hero.

For my part this sudden change in the behavior of the supreme Lama only caused me to heave a heavy sigh for the future of Tibet. It cruelly disillusioned me of the great hopes I had reposed in his character for the welfare of his country. The reason why the Grand Lama, who was at first as timid as a hare towards England, should become suddenly as bold as a lion, is not far to seek. The conclusion of a secret treaty with Russia was at the bottom of the strange phenomenon. Strong in the idea that Russia, as she had promised the Dalai Lama, would extend help whenever his country was threatened by England, he who had formerly trembled at the mere thought of the possibility of England’s encroachment began now to hurl defiance at her. He may even have thought that the arrival of a large number of arms from Russia would enable Tibet to resist England single-handed. In short, the Dalai Lama believed that Russia being the only country in the world strong enough to thwart England, therefore he need no longer be harassed by any fear of the latter country.

With the Dalai Lama—perhaps one of the greatest Lama pontiffs that has ever sat on the throne—given up shamelessly, and even with exultation, to that servile thought of subserviency, and with no great men prepared to uphold the independence of the country, Tibet must be looked upon as doomed. All things considered therefore, unless some miracle should happen, she is sure to be absorbed by[530] some strong Power sooner or later, and there is no hope that she will continue to exist as an independent country.

-- Three Years in Tibet, by Shramana Ekai Kawaguchi