by Wikipedia

Accessed: 1/11/20

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

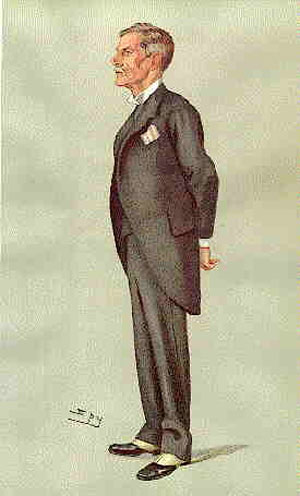

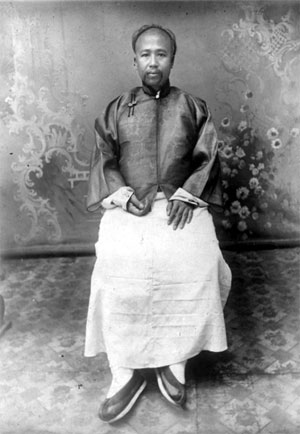

Homer Lea

Born November 17, 1876

Denver, Colorado, U.S

Died November 11, 1912 (aged 35)

California, U.S.

Nationality American

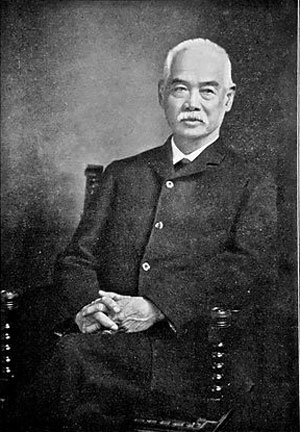

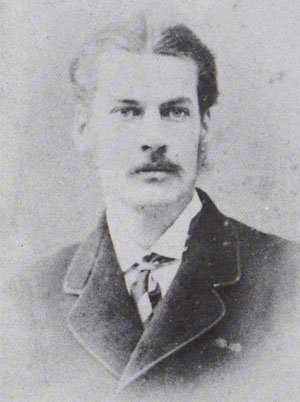

Alma mater Stanford University

Homer Lea (November 17, 1876 – November 1, 1912) was an American adventurer, author and geopolitical strategist. He is today best known for his involvement with Chinese reform and revolutionary movements in the early twentieth century and as a close advisor to Dr. Sun Yat-sen during the 1911 Chinese Republican revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty, and for his writings about China and geopolitics.

Early life

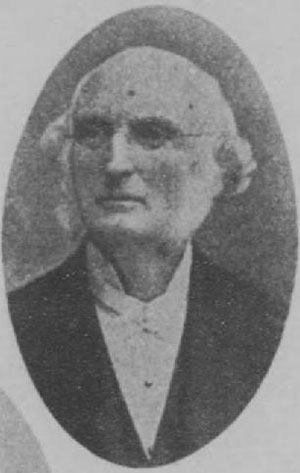

Homer Lea was born in Denver, Colorado, to Alfred E. (1845–1909) and Hersa A. (1846–1879; née Coberly) Lea. He had two younger sisters, Ermal and Hersa. Alfred, a Tennessee native, had a successful real estate, abstract and brokerage business in Boulder, Colorado. After his wife Hersa died from an unexpected illness in 1879, he married Emma R. Wilson in 1890 and moved his family to Los Angeles, California four years later.[1]

Homer came from a pioneering family. His grandfather, Dr. Pleasant John Graves Lea (1807-1862), helped establish the town of Cleveland, Tennessee, in 1837, before moving his family to Jackson County, Missouri, in the late 1840s in search of new opportunities. He is the namesake for Lee's Summit, Missouri. The town was named after him in 1868 when the Missouri Pacific Railroad established a station near his property, which was the highest point of its St. Louis-Omaha line, but misspelled his name. In 1884, Alfred Lea was involved in the establishment of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, and the following year helped his brother Joseph establish the town of Roswell, New Mexico, by surveying and drawing the first plat of the Roswell town site. In 1917, Joseph C. Lea (1841-1905), Alfred's brother, became the namesake for Lea County, New Mexico.[2] [3]

Homer was born seemingly healthy, but after suffering a drop as a baby, he became a hunchback, eventually standing five feet in height and weighing approximately 100 pounds. At about age 12 he went to the National Surgical Institute in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he received medical treatment that helped improve his stature. His health began deteriorating further from a degenerative kidney ailment known as Bright's disease and he suffered chronic headaches and vision problems that may have stemmed from a diabetic condition.[4]

Homer attended Boulder Central School (1886–1887), East Denver High School (1892–1893), the University of the Pacific college preparatory academy in San Jose, California (1893–1894), and Los Angeles High School (1894–1896). He planned on going to Harvard University and becoming a lawyer, but financial setbacks altered his plans and he attended Occidental College in Los Angeles (1897–1898) for his freshman college year and Stanford University (1898–1899) for his sophomore and junior years, before dropping out of school for health reasons.[5]

Homer was an avid reader, a charismatic debater, and an accomplished outdoorsman who refused to be bound by the limitations of his disabilities. He loved reading military history and particularly admired Napoleon, in part because he considered that the Emperor's slight stature (now, incidentally, known to be a myth) was an example of greatness unaffected by physical size. He excelled as a debater and developed effective skills in influencing others. He became president of the Los Angeles High School debating society and later president of the local Lyceum League national debating society chapter. He loved adventure and the outdoors and often went on rugged camping trips where he always carried his own weight.[6]

Chinese affairs

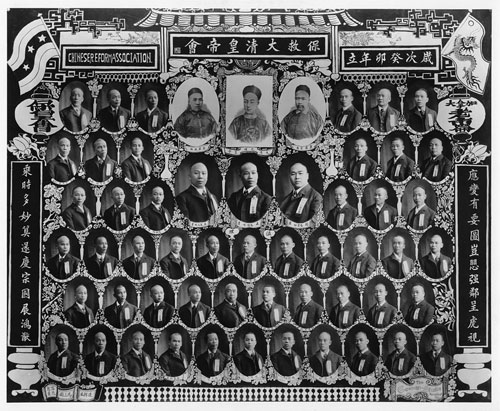

Lea developed an interest in China after his family moved to Los Angeles, seeing in China an opportunity to attain military glory. He often visited nearby Chinatown and also befriended the Reverend Ng Poon Chew, a local Chinese missionary friend of his parents. He met other Chinese through Ng Poon Chew and soon began learning Cantonese. In 1899, while recuperating from a bout of smallpox, he learned of a recently organized Chinese society called the Bao Huang Hui (Protect the Emperor Society; also known as the Chinese Empire Reform Association), which Kang Youwei, a former adviser to the Chinese emperor, helped establish to restore the Guangxu Emperor to his throne. The emperor had been deposed in 1898 by Empress Dowager Cixi for instituting Western reforms.[7]

Lea saw an opportunity for adventure in China with the Bao Huang Hui rather than returning to Stanford. He convinced local Bao Huang Hui leaders that he was a military expert who could greatly benefit their cause, in part, by falsely claiming Confederate army general Robert E. Lee as a relative. Chinese officials were also impressed by his extensive Stanford education. The Bao Huang Hui welcomed him into their ranks with promises of becoming a general in their upcoming military campaign to restore the emperor to power. He traveled to China in 1900, while the Boxer Uprising was underway, with high hopes of playing a major role in the military campaign. He became a lieutenant general in the Bao Huang Hui's makeshift military forces, but had a relatively unimportant assignment that involved training rural volunteers away from any active military operations. After the Bao Huang Hui's main military forces were defeated by the imperial army, his military adventures in China came to a virtual end.[8]

Lea returned to California in 1901 and continued working with the Bao Huang Hui. He became the architect of a plan to train a Bao Huang Hui military cadre in America whose goal was to return to China and help restore the emperor to power. In 1904, he began establishing a network of military schools nationwide to covertly train his soldiers. His soldiers wore uniforms similar to those of the U.S. Army, with the exception of having a dragon replacing the national eagle on buttons and hats, and he recruited U.S. Army veterans as drill instructors. While his training scheme received popular attention in the press, it also resulted in a series of unwanted federal, state and local investigations, which subsequently led Kang Youwei to disavow Lea and his training scheme.[9]

After breaking with the Bao Huang Hui, Lea again turned his ambitions to China. In 1908, he unsuccessfully sought to become a U.S. trade representative to China for the Roosevelt administration; and in 1909, he unsuccessfully sought to become the U.S. Minister to China for the Taft administration. In 1908, he also contrived a bold and audacious military venture in China called the "Red Dragon Plan" that called for organizing a revolutionary conspiracy to conquer the two southern Guang provinces. He conspired with a handful of American businessmen and Yung Wing, a prominent former Chinese diplomat and scholar living in America. Through Yung Wing, he planned to solicit a united front of various southern Chinese factions and secret societies to organize an army that he would command for the revolution. If successful, Yung Wing was slated to head a coalition government of revolutionary forces while Lea and his fellow conspirators hoped to receive wide-ranging economic concessions from the new government.[10]

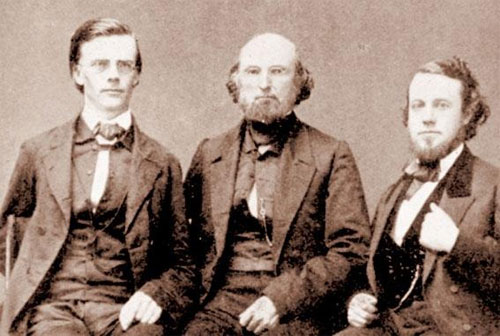

When Chinese revolutionary leader Dr. Sun Yat-sen came to America in late 1909 on a fund-raising trip, he met with Yung Wing, who convinced him that Lea and the Red Dragon conspirators could benefit his revolutionary movement. The Red Dragon conspirators joined Sun Yat-sen's movement to topple the Manchu Dynasty and Lea became one of Sun Yat-sen's most trusted advisors. Ultimately, the Red Dragon conspirators could not obtain the necessary financial backing for their plans and dissolved the conspiracy after a failed revolutionary attempt by Sun Yat-sen's followers in March 1911. Lea, however, remained loyal to Sun Yat-sen.[11]

In October 1911, Sun Yat-sen's forces succeeded in their revolution to depose the Manchu Dynasty. Sun Yat-sen was in America on a fundraising trip when he received word that he was to be the president of the new Chinese provisional government. He immediately contacted Lea to help arrange American and British governmental support for the revolutionary cause. Sun Yat-sen and Lea believed in forming an Anglo-Saxon alliance with China that would grant the United States and Great Britain special status for their support. Lea, who was in Wiesbaden, Germany, receiving medical treatment for his failing eyesight, met Sun Yat-sen in London, but they failed to obtain the desired Anglo-American support.[12]

As Sun Yat-sen and Lea sailed together for China, Lea's influence on Sun Yat-sen appeared to be growing. As their ship made several port calls along the way, Sun Yat-sen announced plans to make Lea the chief of staff of China's Republican army with authority to negotiate an end to hostilities with the imperial government. Shortly after arriving in Shanghai, China, in late December 1911, however, Lea suffered a major reversal of fortunes. He received word from the U.S. State Department that he could not be the chief of staff of China's Republican army since U.S. legal restrictions prevented him from aiding revolutionary movements. At the same time, Chinese revolutionary leaders wary of his influence over Sun Yat-sen, considered him an interloper and wanted nothing to do with him, which further marginalized his position. He remained Sun Yat-sen's close unofficial adviser until early February 1912, when he suffered a near fatal stroke that left him partially paralyzed and signaled an end to his stay in China.[13]

Writings

Homer Lea's principal writings included three books, The Vermilion Pencil (1908), The Valor of Ignorance (1909), and The Day of the Saxon (1912). His first book, The Vermilion Pencil, a romance novel, received critical acclaim. The novel painted a colorful picture of Chinese rural life with a fast moving plot that centered on the relationship and romance of a French missionary and the young wife of a Chinese Viceroy. Lea originally entitled it, The Ling Chee, (or lingchi in the present romanization) in reference to a type of Chinese execution by dismemberment. His publisher, McClure's, insisted on the change. Lea collaborated with Oliver Morosco, the proprietor of the Burbank Theater in Los Angeles, to produce a dramatized version of The Ling Chee in the fall of 1907, but nothing came of the venture. Lea subsequently wrote a dramatized version of his novel that he renamed The Crimson Spider. In 1922, Japanese-born Sessue Hayakawa, a leading Hollywood film star and movie producer, adapted The Vermilion Pencil to the screen.[14]

Lea's second book, The Valor of Ignorance, examined American defense and in part prophesied a war between America and Japan. It created controversy and instantly elevated his reputation as a credible geo-political spokesman. Two retired U.S. Army generals, including former Army Chief-of-Staff Adna R. Chaffee, wrote glowing introductions to the book, which also contained a striking frontispiece photograph of Lea in his lieutenant general's uniform. The book contained maps of a hypothetical Japanese invasion of California and the Philippines and was very popular among American military officers, particularly those stationed in the Philippines over the next generation. General Douglas MacArthur and his staff, for example, paid close attention to the book in planning the defense of the Philippines. The Japanese military also paid close attention to the book, which was translated into Japanese.[15] Carey McWilliams attributed to this book's depiction of a local fifth column the instigation of the modern anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States that would eventually lead to the internment of Japanese Americans.[16]

Lea's final book, The Day of the Saxon, repeated the prophecy of war between America and Japan. Japan, it said, must gain control of the Pacific before extending her sovereignty on the Asian continent. Japan's maritime frontiers must extend eastward of the Hawaiian Islands and southward of the Philippines. "Because of this Japan draws near to her next war—a war with America—by which she expects to lay the true foundation of her greatness." (1912: 92). Lea criticized the United States for its "indifference," party politics, and the lack of militarism which increase the chance of victory for Japan (1912: 92-93). The Day of the Saxon examined British imperial defense and predicted the break-up of the British Empire. It too generated controversy and received most of its critical attention in Europe. In The Day of the Saxon Lea believed the entire Anglo-Saxon race faced a threat from German (Teuton), Russian (Slav), and Japanese expansionism: The "fatal" relationship of Russia, Japan, and Germany "has now assumed through the urgency of natural forces a coalition directed against the survival of Saxon supremacy." It is "a dreadful Dreibund." (1912: 122) Lea believed that while Japan moved against Far East and Russia against India, the Germans would strike at England, the center of the British Empire. He thought the Anglo-Saxons faced certain disaster from their militant opponents.[17] Two Pacts—Non-Aggression between Germany and Russia in 1939 and Neutrality between Russia and Japan in April 1941—much approached Lea's prophecy, but the German decision to attack Russia in June 1941 prevented the prophecy from coming true. Lea considered the possibility of war between Germany and Russia but did not believe that this war will take place before the defeat of the British Empire because the German-Russian war would be mutually disastrous for both (1912: 124-125).

In The Valor of Ignorance and The Day of the Saxon, Lea viewed American and British struggles for global competition and survival as part of a larger Anglo-Saxon social Darwinist contest between the "survival of the fittest" races. He sought to make all English-speaking peoples see that they were in a global competition for supremacy against the Teutonic, Slavic, and Asian races. He believed that once awakened, they would embrace his militant doctrines and prepare for the coming global onslaught. China figured prominently in his world-view as a key ally with the Anglo-Saxons in counterbalancing other regional and global competitors. He had plans for a third volume to complete a trilogy with The Valor of Ignorance and The Day of the Saxon, in which he sought to advance his social Darwinist beliefs by discussing the spread of democracy among nations, but he died before beginning the volume.[18]

Later life and death

Homer Lea's grave

Lea returned to California in May 1912 to recover his health. He had hopes of rejoining Sun Yat-sen, but he suffered another stroke in late October 1912, which proved fatal. His final wishes were to be buried in China, but his cremated ashes remained with his family until they arranged for the Republic of China to receive them. In 1969, his ashes and those of his wife Ethel (née Bryant) were interred at Wuzhi Mountain Military Cemetery in Yangmingshan National Park in Taipei, Taiwan. President Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen's brother-in-law, took a personal interest in the arrangements. He believed the interment of the Lea's ashes in Taiwan should only be temporary until they could be transferred to Nanking and interred by Sun Yat-sen's mausoleum, when Taiwan and mainland China were finally reunited.[19]

In popular culture

Homer Lea is portrayed by Michael Lacidonia in the film 1911, released in 2011.

Bibliography

Major Works by

• 1908 The Vermilion Pencil; a Romance of China. New York: McClure. 1908. Internet Archive 30756368

Reprinted 2003. - Stirling: Read Around Asia. - ISBN 978-0-9545450-0-0

Reprinted 2017. - Special Revised Edition Edited by Lawrence M. Kaplan: Amazon/Createspace.com - ISBN 978-1979429610

• 1909: The Crimson Spider. - Unpublished

Reprinted 2017. - Edited by Lawrence M. Kaplan: Amazon/Createspace.com - ISBN 978-1547091829

• 1909: The Valor of Ignorance. - New York & London: Harper and Brothers. - 1178360

Reprinted 1942. - ISBN 1-931541-66-3

• 1912: The Day of the Saxon. -New York & London: Harper and Brothers. - 250316

Reprinted 1942. ISBN 1-932512-02-0

Major Works about

• Anschel, Eugene, (1984). - Homer Lea, Sun Yat-Sen, and the Chinese Revolution. - Praeger Pubs. ISBN 0-03-000063-7

• Alexander, Tom, (July, 1993). - "The Amazing Prophecies of "General" Homer Lea". - Smithsonian. - p. 102.

• Kaplan, Lawrence (Sept. 15, 2010). - Homer Lea: American Soldier of Fortune (American Warriors Series). - The University Press of Kentucky. - ISBN 0-8131-2616-9

• O'Reilly, Tex and Thomas, Lowell, (). - "Born to Raise Hell". - p. 141-148. - ISBN 1-59048-109-7

Notes

1. Kaplan, Lawrence Homer Lea: American Soldier of Fortune.

2. Kaplan, Homer Lea

3. http://www.leacounty.net/about.html

4. Kaplan, Homer Lea

5. Kaplan, Homer Lea

6. Kaplan, Homer Lea

7. Kaplan, Homer Lea

8. Kaplan, Homer Lea

9. Kaplan, Homer Lea

10. Kaplan, Homer Lea

11. Kaplan, Homer Lea

12. Kaplan, Homer Lea

13. Kaplan, Homer Lea

14. Kaplan, Homer Lea

15. Kaplan, Homer Lea.

16. McWilliams, Carey (1944). Prejudice - Japanese Americans: Symbol of Racial Intolerance. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 40–45.

17. Kaplan, Homer Lea.

18. Kaplan, Homer Lea.

19. Kaplan, Homer Lea.

External links

• The Homer Lea Research Center – developed by Lea's biographer Dr. Lawrence M. Kaplan

• Homer Lea's remains arriving at Taipei, Songshan Airport (video)

• Homer Lea at Library of Congress Authorities, with 11 catalog records