by Wikipedia

Accessed: 1/12/20

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Brothers in Unity is a four-year secret society at Yale University. It used to be a debating society.

The Society of Brothers in Unity

Motto E parvis oriuntur magna

Formation 1768

Legal status Active

Location

Yale University

Region

New Haven, Connecticut

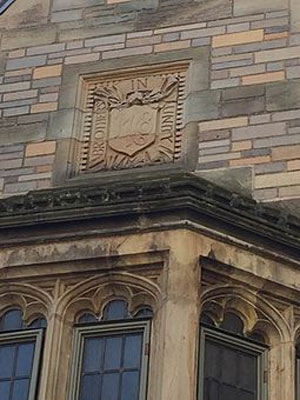

References to Brothers in Unity can be found throughout Yale's campus, including several within the courtyards of Branford College

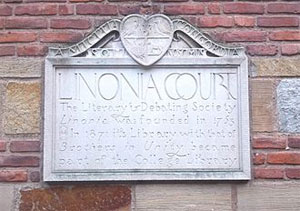

Brothers in Unity shares several memorials with the Linonia Society

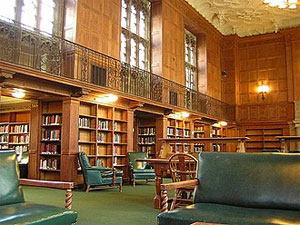

The Linonia and Brothers in Unity Room in the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale

History

Founding

The Society of Brothers in Unity at Yale College was founded by 21 members of the Yale classes of 1768, 1769, 1770 and 1771.[1] The founders included David Humphreys, who is noted in the society's public 1841 catalogue as the "cornerstone" of the founding class.[1] The society was founded chiefly to combat existing class separation among literary societies; prior to 1768, Yale freshmen were not "received into any Society", and junior society members were forced into the servitude of seniors "under dread of the severest penalties".[2] Humphreys, a freshman of the class of 1771, persuaded two members of the senior class, three junior class members, two sophomores, and 14 freshmen to support the society's founding.

There were many revolutionaries and groups that wanted to overthrow the Qing government to re-establish Han-led government. The earliest revolutionary organizations were founded outside of China, such as Yeung Ku-wan's Furen Literary Society, created in Hong Kong in 1890....

In January 1911, the revolutionary group Zhengwu Xueshe (振武學社) was renamed as Wenxueshe (Literary society)...

The Literary Society (文學社) and the Progressive Association (共進會) were revolutionary organizations involved in the uprising that mainly began with a Railway Protection Movement protest.

-- Xinhai Revolution [Chinese Revolution of 1911], by Wikipedia

Early activity

Immediately after its conception, the society's unorthodox class composition was allegedly challenged by other literary groups at Yale College.[2] According to its catalogue, Brothers in Unity only became an independent institution after persevering "an incessant war" waged by multiple traditional societies who did not support the concept of a four-year debating community. It is speculated that this struggle initiated the Brothers' near 250-year rivalry with Linonia, which previously did not initiate freshman members. Within a year, however, Brothers in Unity became fully independent, its popularity influencing other societies to reconsider their exclusion of first year students. The Yale College freshman class of 1771 yielded 15 members of Brothers in Unity, while Linonia accepted four; the first noted point in which underclassmen were publicly accepted into a Yale society.[1] The Brothers adopted the motto E parvis oriuntur magna between 1768 and 1769.

1768-1841

Between its founding and 1841, the society is said to have followed the template of other debating societies, although operating under "Masonic secrecy," according to 19th century Yale historian Ebenezer Baldwin.[3] In conjunction with Linonia and the Calliopean Society, Brothers in Unity was noted by Baldwin to discuss "scientific questions" and gravitate towards "literary pursuits." This is substantiated by the Brother's own public documentation, which denotes that the society sought "lofty places in science, literature, and oratory" fields, as well as general "intellectual improvement."[1]

The Brotherhood, between the years of 1768 and 1841, claims membership of 15 Supreme Court Justices (seven of which Chief Justices), 6 United States Governors, 13 Senators, 45 Congressional representatives, 14 presidents of colleges and universities, two United States Attorney Generals, and a United States Vice President. In its catalogue, the Brotherhood also asserts: "Every President of the United States, with the exception of two, has had in his cabinet one of our members, and the governor's chair of our own state has been filled for twenty years with Brothers in Unity."[1] 26 Yale valedictorians after the position's 1798 founding are attributed to the Society.

Membership to the Brothers and the Linonian Society divided the students of Yale College beginning in the turn of the 19th century. Both held expansive literary collections, which they used to compete against each other. Between 1780 and 1841, the Brothers claimed right to more volumes than Linonia, although these assertions are disputed[1][4] The two societies' rivalry extended to their membership. Brothers in Unity claims membership of John C. Calhoun, who was alphabetically assigned to Linonia, but had "undiminished attachment" to the Brothers.[1] However, while publications released by both societies repeatedly assert superiority amongst each other, they also express positive sentiment; denoting each other as "ornaments" of Yale and "generous rivals."[5][6][1]

At the time of the formation of Yale's central library, Linonia and 'Brothers in Unity donated their respective libraries to the university. The donation is commemorated in the Linonia and Brothers Reading Room of Yale's Sterling Memorial Library. The reading room contains the Linonia and Brothers (L&B) collection, a travel collection, a collection devoted to medieval history, and a selection of new books recently added to Sterling’s collections.

Actions as a secret society

Following the transformation of Yale's debating societies into the Yale Union, and later, the Yale Political Union, Brothers in Unity and the Linonian Society ceased function as literary and debating societies. Both societies continued their existence in secrecy, recanting their roles as intellectual colloquiums and instead prioritizing power and social influence as paramount. Linonia morphed into the template of other Yale secret societies, although its current existence is still questioned and its membership is not disclosed to the public as of 2012.[7] While unsubstantiated, Linonia is said to participate in Yale's April "tap night," along with the college's senior societies.

Unlike Linonia, Brothers in Unity refrained from association with the customs of Yale's senior societies. The society is rumored to tap a small cohort of members from each class during the fall semester, a notion in line with the organization's 1768 constitution and 1841 catalogue.[1] Internally, the society is referenced as the "Brotherhood," a community stressing unilateral action amongst members to acquire power in the realms of business, politics, and philanthropy. The society is said to have implemented methods of deterrence stemming from its 1768 constitution that prevent brothers from unearthing the identities of fellow members or disclosing internal actions of the brotherhood. However, public knowledge of specific traditions, discussions, and society regulations of Brothers in Unity ended after its 19th-century turn to secrecy, rendering most modern rumor as conjecture. It is rumored that the society maintains "taplines" into several of Yale's most prestigious senior societies, including Skull and Bones, Scroll and Key, Book and Snake, Myth and Sword, Elihu, and Mace and Chain.

Though the society no longer discloses the names of its members, its presence on campus continued through the 19th and 20th centuries, with reported activity spanning into the turn of the 21st century. It is unknown whether men exclusively fill current membership of the Brothers, due to the integration of women into Yale's societal web.

Prominent members

Note

Note: The society's last public catalogue of members was published in 1841. Since the transition of Brothers in Unity into a fully secretive society, the names of members during the 20th and 21st century are unknown.

List

• John C. Calhoun – Class of 1804 – 7th Vice President of the United States, United States Senator, political theorist

• Samuel Morse – Class of 1810 – Inventor of Morse Code, aided development of telegraphy. Namesake of Morse College at Yale

• Nathan Hale – Class of 1773 – Spy for Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. (Also claimed by Linonia)

• Noah Webster – Class of 1778 – United States Founding Father, Author of Merriam-Webster dictionary.

• Theodore Dwight Woolsey – Class of 1820 – President of Yale College, prolific author and academic.

• David Humphreys (soldier) – Class of 1768 – American Revolutionary War colonel and aide to George Washington. Served as the American minister to Portugal and was an entrepreneur who brought Marino sheep to America.

• Morrison Waite – Class of 1837 – 7th Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, champion of education opportunities for blacks.

• Benjamin Silliman – Class of 1796 – Prolific Chemist and Scientist; the first person to distill petroleum, and a founder of the American Journal of Science, the oldest scientific journal in the United States. Namesake of Silliman College at Yale and the mineral Sillimanite.

• Yung Wing – Class of 1854 – First Chinese student to graduate from an American University, businessman, Brothers in Unity librarian.

• Richard Henry Green – Class of 1874 – First African-American to graduate from Yale College, First African-American to earn a Ph.D., 6th American to earn a Ph.D in the field of physics.

• Alphonso Taft – Class of 1833 – 31st United States Secretary of War, 34th United States Attorney General, advocated against anti-African American voting laws.

• Henry Durant – Class of 1827 – Created the University of California, (Berkeley). Was the 16th mayor of Oakland, California.

• Moses Cleaveland – Class of 1777 – Founded Cleveland, Ohio. Commissioned brigadier general of Connecticut militia, surveyed the Western Reserve.

• Stephen Clark Foster – 1840 – First American Mayor of Los Angeles.

• James Gadsden – Class of 1806 – Namesake of the Gadsden Purchase (the United States purchase of Mexico], and appointed Adjunct General of US army.

• James Burnet – Class of 1798 – First Yale valedictorian.

• John Brown of Pittsfield – 1771 – First to alert George Washington to the defection plot of Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. Founding member of Brothers in Unity.

• Peter Buell Porter – Class of 1791 – Served as the 12th United States Secretary of War under president John Quincy Adams, was the 11th Secretary of State of New York, and was elected to the 14th United States Congress.

• William Strong (Pennsylvania judge) – Class of 1828 – Supreme Court Justice.

• Henry Baldwin (judge) – Class of 1797 – Supreme Court Justice and United States Representative.

• John M. Clayton – Class of 1815 – 18th United States Secretary of State, United States Senator

• George Edmund Badger – Class of 1816 (did not graduate) – 12th United States Secretary of the Navy and United States Senator

• William Channing Woodbridge – Class of 1812 – Geographer and educational reformer.

• Chauncey Goodrich – Class of 1776 – Senator and Representative of Connecticut, 8th Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut.

• Joel Barlow – Class of 1778 – Ambassador to France, drafter of the Treaty of Tripoli in 1796.

• Thomas Hill Hubbard – Class of 1799 – Three time Presidential Elector and two time United States representative.

• Uriah Tracy – Class of 1778 – First respondent to the Lexington Alarm during the early American Revolutionary War. United States Senator and Representative from Connecticut.

• Ray Greene – Class of 1784 – United States Senator and Attorney General from Rhode Island.

• Israel Smith – Class of 1781 – Dominated Vermont politics; Governor of Vermont, Senator, and member of the United States House of Representatives.

• John Davis (Massachusetts governor) – Class of 1812 – Two time Governor of Massachusetts in 1834 and 1841, respectively, United States Senator, and member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

• John Elliott – Class of 1794 – United States Senator from Georgia.

• Henry Meigs – Class of 1799 – United States Senator from New York state.

• William Hull – Class of 1772 – General in the War of 1812, appointed by Thomas Jefferson as Governor of Michigan, soldier in Revolutionary War.

• Oliver Wolcott – Class of 1778 – United States Secretary of the Treasury and 24th Governor of Connecticut.

• William Edmond – Class of 1778 – Successor to James Davenport in the United States House of Representatives from Connecticut, fought in the Revolutionary War in the Revolutionary Army.

• Christopher Ellery – Class of 1787 – United States Senator from Rhode Island.

• Leonard Bacon – Class of 1820 – Influential abolitionist and congregational preacher.

• Jeremiah Evarts – Class of 1802 – Christian missionary, reformer, and activist for the rights of American Indians in the United States, and a leading opponent of the Indian removal policy of the United States government.

• James Lanman – Class of 1788 – Member of 8th United States Senate from Connecticut. Namesake of Lanman-Wright Hall in the Old Campus of Yale University.

References

1. Robinson, W.E. (1841). "Preface". A Catalogue of the Society of Brothers in Unity, Yale College, Founded 1768. New Haven, CT: Hitchcock & Stafford. pp. 1–6. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

2. Quoted remarks are the opinions of the Brothers in Unity Society of 1841, on page 2 of its catalogue

3. History of Yale College: From Its Foundation, A.D. 1700, to the Year 1838. Ebenezer Baldwin, Esq. Page 235.

4. See also: History of Yale College: From Its Foundation, A.D. 1700, to the Year 1838. Ebenezer Baldwin, Esq. Page 235-236

5. The Linonian Society Library of Yale College: The First Years, 1768—1790

6. Kathy M. Umbricht Straka The Yale University Library Gazette, Vol. 54, No. 4 (April 1980), pp. 183-192

7. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-11. Retrieved 2014-12-01.