Part 2 of 2

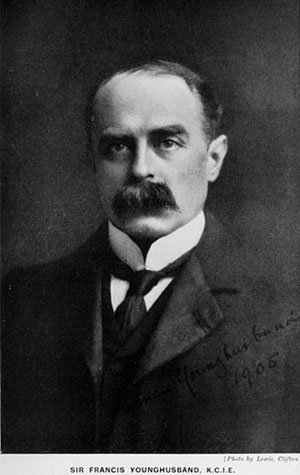

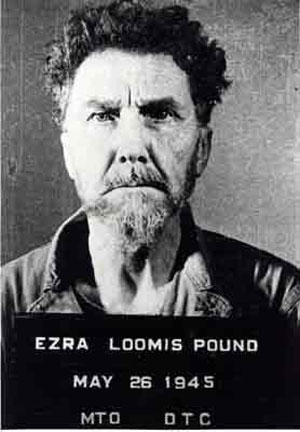

Views and relationshipsAlthough Pound repudiated his antisemitism in public, he maintained his views in private. He refused to talk to psychiatrists with Jewish-sounding names, dismissed people he disliked as "Jews", and urged visitors to read the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903), a forgery claiming to represent a Jewish plan for world domination.[124] He struck up a friendship with the conspiracy theorist and antisemite Eustace Mullins, believed to be associated with the Aryan League of America, and author of the 1961 biography This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound.[133]

Even more damaging was his friendship with John Kasper, a far-right activist and Ku Klux Klan member. Kasper had come to admire Pound during literature classes at university, and after he wrote to Pound in 1950 the two had become friends. Kasper opened a bookstore in Greenwich Village in 1953 called "Make it New", reflecting his commitment to Pound's ideas; the store specialized in far-right material, including Nazi literature, and Pound's poetry and translations were displayed on the window front.[134] Kasper and another follower of Pound's, David Horton, set up a publishing imprint, Square Dollar Series, which Pound used as a vehicle for his tracts about economic reform.[135] Wilhelm writes that there were a lot of conventional people visiting Pound too, such as the classicist J.P. Sullivan and the writer Guy Davenport, but it was the association with Mullins and Kasper that stood out and delayed his release from St Elizabeths.[133][135]

ReleasePound's friends continued to try to get him out. Shortly after Hemingway won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, he told Time magazine that "this would be a good year to release poets".[136] The poet Archibald MacLeish asked Hemingway in June 1957 to write a letter on Pound's behalf. Hemingway believed Pound was unable to abstain from awkward political statements or from friendships with people like Kasper, but he signed a letter of support anyway and pledged $1,500 to be given to Pound when he was released.[137] In an interview for the Paris Review in early 1958, Hemingway said that Kasper should be jailed and Pound released.[138] Kasper was eventually jailed, for inciting a riot in connection with the Hattie Cotton School in Nashville, targeted because a black girl had registered as a student. He was also questioned relating to the bombing of the school.[139]

Several publications began campaigning for Pound's release in 1957. Le Figaro published an appeal entitled "The Lunatic at St Elizabeths". The New Republic, Esquire and The Nation followed suit; The Nation argued that Pound was a sick and vicious old man, but had rights. In 1958 MacLeish hired Thurman Arnold, a prestigious lawyer who ended up charging no fee, to file a motion to dismiss the 1945 indictment. Overholser, the hospital's superintendent, supported the application with an affidavit saying Pound was permanently and incurably insane, and that confinement served no therapeutic purpose.[140] The motion was heard on 18 April 1958 by the judge who had committed Pound to St Elizabeths. The Department of Justice did not oppose the motion, and Pound was free.[141][142]

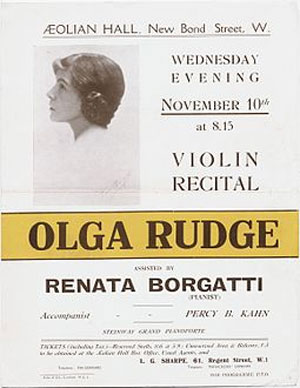

Italy (1958–1972)Pound arrived in Naples in July 1958, where he was photographed giving a fascist salute to the waiting press. When asked when he had been released from the mental hospital, he replied: "I never was. When I left the hospital I was still in America, and all America is an insane asylum."[143] He and Dorothy went to live with Mary at Schloss Brunnenburg, near Merano in the Province of South Tyrol, where he met his grandson, Walter, and his granddaughter, Patrizia, for the first time, then returned to Rapallo, where Olga Rudge was waiting to join them.[144]

They were accompanied by a teacher Pound had met in hospital, Marcella Spann, 40 years his junior, ostensibly acting as his secretary and collecting poems for an anthology. The four women soon fell out, vying for control over him; Canto CXIII: alluded to it: "Pride, jealousy and possessiveness / 3 pains of hell." Pound was in love with Spann, seeing in her his last chance for love and youth. He wrote about her in Canto CXIII: "The long flank, the firm breast / and to know beauty and death and despair / And to think that what has been shall be, / flowing, ever unstill." Dorothy had usually ignored his affairs, but she used her legal power over his royalties to make sure Spann was seen off, sent back to the United States.[144]

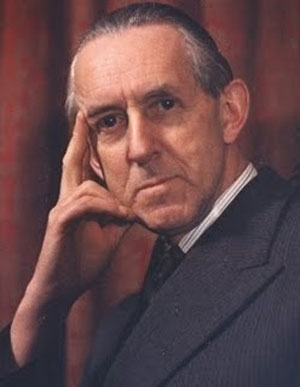

By December 1959, Pound was mired in depression. He saw his work as worthless and The Cantos botched. In a 1960 interview given in Rome to Donald Hall for Paris Review, he said: "You—find me—in fragments." Hall wrote that he seemed in an "abject despair, accidie, meaninglessness, abulia, waste". He paced up and down during the three days it took to complete the interview, never finishing a sentence, bursting with energy one minute, then suddenly sagging, and at one point seemed about to collapse. Hall said it was clear that he "doubted the value of everything he had done in his life".[145]

Those close to him thought he was suffering from dementia, and in mid-1960, Mary placed him in a clinic near Merano when his weight dropped. He picked up again, but by early 1961 he had a urinary infection. Dorothy felt unable to look after him, so he went to live with Olga in Rapallo, then Venice; Dorothy mostly stayed in London after that with Omar. Pound attended a neo-Fascist May Day parade in 1962, but his health continued to decline. The following year he told an interviewer, Grazia Levi: "I spoil everything I touch. I have always blundered ... All my life I believed I knew nothing, yes, knew nothing. And so words became devoid of meaning."[146]

William Carlos Williams died in 1963, followed by Eliot in 1965. Pound went to Eliot's funeral in London and on to Dublin to visit Yeats's widow. Two years later he went to New York where he attended the opening of an exhibition featuring his blue-inked version of Eliot's The Waste Land.[147] He went on to Hamilton College where he received a standing ovation.[148]

Pound's grave on the Isola di San Michele

Pound's grave on the Isola di San MicheleShortly before his death in 1972 it was proposed that he be awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, but after a storm of protest the academy's council opposed it by 13 to 9. The sociologist Daniel Bell, who was on the committee, argued that it was important to distinguish between those who explore hate and those who approve it. Two weeks before he died, Pound read for a gathering of friends at a café: "re usury/ I was out of focus, taking a symptom for a cause. / The cause is avarice."[148]

On his 87th birthday, 30 October 1972, he was too weak to leave his bedroom. The next night he was admitted to the Civil Hospital of Venice, where he died in his sleep of an intestinal blockage on 1 November, with Olga at his side. Dorothy was unable to travel to the funeral. Four gondoliers dressed in black rowed the body to the island cemetery, Isola di San Michele, where he was buried near Diaghilev and Stravinsky.[149] Dorothy died in England the following year. Olga died in 1996 and was buried next to Pound.[147]

StyleCritics generally agree that Pound was a strong yet subtle lyricist, particularly in his early work, such as "The River Merchant's Wife".[150] According to Witmeyer a modern style is evident as early as Ripostes, and Nadel sees evidence of modernism even before he began The Cantos, writing that Pound wanted his poetry to represent an "objective presentation of material which he believed could stand on its own" without use of symbolism or romanticism.[151]

Drawing on literature from a variety of disciplines, Pound intentionally layered often confusing juxtapositions, yet led the reader to an intended conclusion, believing the "thoughtful man" would apply a sense of organization and uncover the underlying symbolism and structure.[152] Ignoring Victorian and Edwardian grammar and structure, he created a unique form of speech, employing odd and strange words, jargon, avoiding verbs, and using rhetorical devices such as parataxis.[153]

Pound's relationship to music is essential to his poetry. Although he was tone deaf and his speaking voice is described as "raucous, nasal, scratchy", Michael Ingam writes that Pound is on a short list of poets possessed of a sense of sound, an "ear" for words, imbuing his poetry with melopoeia.[154] His study of troubadour poetry—words written to be sung (motz et son)—led him to think modern poetry should be written similarly.[154] He wrote that rhythm is "the hardest quality of a man's style to counterfeit".[155] Ingham compares the form of The Cantos to a fugue; without adhering strictly to the traditions of the form, nevertheless multiple themes are explored simultaneously. He goes on to write that Pound's use of counterpoint is integral to the structure and cohesion of The Cantos, which show multi-voiced counterpoint and, with the juxtaposition of images, non-linear themes. The pieces are presented in fragments "which taken together, can be seen to unfold in time as music does".[156]

Imagism and Vorticism Dorothy Shakespear designed the Vorticism-inspired cover art for Pound's 1915 Ripostes.

Dorothy Shakespear designed the Vorticism-inspired cover art for Pound's 1915 Ripostes.Opinion varies about the nature of Pound's writing style. Nadel writes that imagism was to change Pound's poetry.[151] Like Wyndham Lewis, Pound reacted against decorative flourishes found in Edwardian writing, saying poetry required a precise and economic use of language and that the poet should always use the "exact" word, stripping the writing down to the "barest essence".[157] According to Nadel, "Imagism evolved as a reaction against abstraction ... replacing Victorian generalities with the clarity in Japanese haiku and ancient Greek lyrics."[151] Daniel Albright writes that Pound tried to condense and eliminate "all but the hardest kernel" from a poem, such as in the two-line poem "In a Station of the Metro".[158] However, Pound learned that Imagism did not lend itself well to the writing of an epic, so he turned to the more dynamic structure of Vorticism for The Cantos.[158]

TranslationsPound's translations represent a substantial part of his work. He began his career with translations of Occitan ballads and ended with translations of Egyptian poetry. Yao says the body of translations by modernist poets in general, much of which Pound started, consists of some of the most "significant modernist achievements in English".[159] Pound was the first English language poet since John Dryden, some three centuries earlier, to give primacy to translations in English literature. The fullness of the achievement for the modernists is that they renewed interest in multiculturalism, multilingualism, and, perhaps of greater importance, they treated translations not in a strict sense of the word but instead saw a translation as the creation of an original work.[160]

Michael Alexander writes that, as a translator, Pound was a pioneer with a great gift of language and an incisive intelligence. He helped popularize major poets such as Guido Cavalcanti and Du Fu, and brought Provençal and Chinese poetry to English-speaking audiences. He revived interest in the Confucian classics and introduced the west to classical Japanese poetry and drama. He translated and championed Greek, Latin and Anglo-Saxon classics, and helped keep them alive at a time when poets no longer considered translations central to their craft.[161]

In Pound's Fenollosa translations, unlike previous American translators of Chinese poetry, which tended to work with strict metrical and stanzaic patterns, Pound created free verse translations. Whether the poems are valuable as translations continues to be a source of controversy.[162] Hugh Kenner contends that Cathay should be read primarily as a work about World War I, not as an attempt at accurately translating ancient Eastern poems. The real achievement of the book, Kenner argues, is in how it combines meditations on violence and friendship with an effort to "rethink the nature of an English poem". These ostensible translations of ancient Eastern texts, Kenner argues, are actually experiments in English poetics and compelling elegies for a warring West.[163] Pound scholar Ming Xie explains that Pound's use of language in his translation of "The Seafarer" is deliberate, in that he avoids merely "trying to assimilate the original into contemporary language".[162]

The CantosFurther information: List of cultural references in The Cantos

And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly sea, and

We set up mast and sail on that swart ship,

Bore sheep aboard her, and our bodies also

Heavy with weeping, and winds from sternward

Bore us out onward with bellying canvas,

Circe's this craft, the trim-coifed goddess.

Then sat we amidships, wind jamming the tiller,

Thus with stretched sail, we went over sea til day's end.

— Canto I (1917)

The Cantos is difficult to decipher. In the epic poem, Pound disregards literary genres, mixing satire, hymns, elegies, essays and memoirs.[164] Pound scholar Rebecca Beasley believes it amounts to a rejection of the 19th-century nationalistic approach in favor of early-20th-century comparative literature. Pound reaches across cultures and time periods, assembling and juxtaposing "themes and history" from Homer to Ovid and Dante, from Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and many others. The work presents a multitude of protagonists as "travellers between nations". The nature of The Cantos, she says, is to compare and measure among historical periods and cultures and against "a Poundian standard" of modernism.[165]

Pound layered ideas, cultures and historical periods, writing in as many as 15 different languages, using modern vernacular, Classical languages and Chinese ideograms.[166] Ira Nadel says The Cantos is an epic, that is "a poem including history", and that the "historical figures lend referentiality to the text". It functions as a contemporary memoir, in which "personal history [and] lyrical retrospection mingle"—most clearly represented in the Pisan Cantos.[164] Michael Ingham sees in The Cantos an American tradition of experimental literature, writing about it, "These works include everything but the kitchen sink, and then add the kitchen sink".[167] In the 1960s William O'Connor described The Cantos as filled with "cryptic and gnomic utterances, dirty jokes, obscenities of various sorts".[168]

Allen Tate believes the poem is not about anything and is without beginning, middle or end. He argues that Pound was incapable of sustained thought and "at the mercy of random flights of 'angelic insight,' an Icarian self-indulgence of prejudice which is not checked by a total view to which it could be subordinated".[169] This perceived lack of logical consistency or form is a common criticism of The Cantos.[170] Pound himself felt this absence of form was his great failure, and regretted that he could not "make it cohere".[171]

Literary criticism and economic theoryPound's literary criticism and essays are, according to Massimo Bacigalupo, a "form of intellectual journal". In early works, such as The Spirit of Romance and "I Gather the Limbs of Osiris", Pound paid attention to medieval troubadour poets—Arnaut Daniel and François Villon. The former piece was to "remain one of Pound's principal sourcebooks for his poetry"; in the latter he introduces the concept of "luminous details".[172] The leitmotifs in Pound's literary criticism are recurrent patterns found in historical events, which, he believed, through the use of judicious juxtapositions illuminate truth; and in them he reveals forgotten writers and cultures.[173]

Pound wrote intensively about economic theory with the ABC of Economics and Jefferson and/or Mussolini, published in the mid-1930s right after he was introduced to Mussolini. These were followed by The Guide to Kulchur, covering 2500 years of history, which Tim Redman describes as the "most complete synthesis of Pound's political and economic thought".[174] Pound thought writing the cantos meant writing an epic about history and economics, and he wove his economic theories throughout; neither can be understood without the other.[175] In these pamphlets and in The ABC of Reading, he sought to emphasize the value of art and to "aestheticize the political", written forcefully, according to Nadel, and in a "determined voice".[176] In form his criticism and essays are direct, repetitive and reductionist, his rhetoric minimalist, filled with "strident impatience", according to Pound scholar Jason Coats, and frequently failing to make a coherent claim. He rejected traditional rhetoric and created his own, although not very successfully, in Coats's view.[177]

Reception

Critical receptionIn 1922, the literary critic Edmund Wilson reviewed Pound's latest published volume of poetry, Poems 1918–21, and took the opportunity to provide an overview of his estimation of Pound as poet. In his essay on Pound, titled "Ezra Pound's Patchwork", Wilson wrote:

Ezra Pound is really at heart a very boyish fellow and an incurable provincial. It is true that he was driven to Europe by a thirst for romance and color that he could scarcely have satisfied in America, but he took to Europe the simple faith and pure enthusiasm of his native Idaho. ... His sophistication is still juvenile, his ironies are still clumsy and obvious, he ridicules Americans in Europe not very much simpler than himself ...[178]

According to Wilson, the lines in Pound's poems stood isolated, with fragmentary wording contributing to poems that "do not hang together". Citing Pound's first seven cantos, Wilson dubbed the writing "unsatisfactory". He found The Cantos disjointed and its contents reflecting a too-obvious reliance on the literary works of other authors, and an awkward use of Latin and Chinese translations as a device inserted among reminiscences of Pound's own life.[178]

The rise of New Criticism during the 1950s, in which author is separated from text, secured Pound's poetic reputation.[179] Nadel writes that the publication of T.S. Eliot's Literary Essays in 1954 "initiated the recuperation of Ezra Pound". Eliot's essays coincided with the work of Hugh Kenner, who visited Pound extensively at St. Elizabeths.[180] Kenner wrote that there was no great contemporary writer less read than Pound, adding that there is also no one to appeal more through "sheer beauty of language".[181] Along with Donald Davie, Kenner brought a new appreciation to Pound's work in the 1960s and 1970s.[182] Donald Gallup's Pound bibliography was published in 1963 and Kenner's The Pound Era in 1971.[180] In the 1970s a literary journal dedicated to Pound studies (Paideuma) was established, and Ronald Bush published the first dedicated critical study of The Cantos, to be followed by a number of research editions of The Cantos.[180]

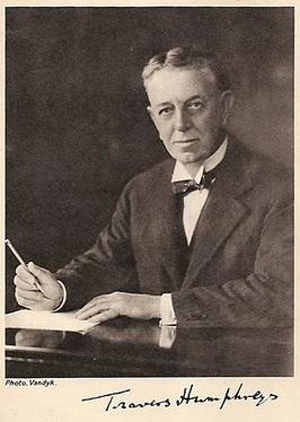

Following Mullins' biography, described by Nadel as "partisan" and "melodramatic", was Noel Stock's factual 1970 Life of Ezra Pound, although the material included was subject to Dorothy's approval. The 1980s saw three significant biographies: John Tytell's "neutral" account in 1987, followed by Wilhelm's multi-volume biography. Humphrey Carpenter's sprawling narrative, a "complete life", built on what Stock began; unlike Stock, Carpenter had the benefit of working without intervention from Pound's relatives. In 2007 David Moody published the first of his multi-volume biography, combining narrative with literary criticism, the first work to link the two.[183]

In the 1980s Mary de Rachewiltz released the first dual-language edition of The Cantos, including "Canto LXXII" and "Canto LXXIII".[184] These cantos had originally been published in fascist magazines, and are characterized by 21st-century literary scholars as no more than war-time propaganda.[185] In 1991 a complete facsimile edition of Pound's prose and poetry was published, now considered a "fundamental research tool", according to Nadel.[184] Scholarship in the 1990s turned toward in-depth investigations of his antisemitism and Rome years. Tim Redman writes about Pound's fascism and his relationship with Mussolini, and Leon Surrette about Pound's economic theories, especially during the Italian period, investigating how Pound the poet became Pound the fascist.[186] In 1999 Surrette wrote about the state of Pound criticism, that "the effort to uncover coherence in a ... crazy quilt of verse styles, critical principles, crankish economic theories and distasteful political affiliations has made it difficult to perceive the genesis and development of any of these components". He emphasized that Pound's "economic and political opinions have not been properly dated, nor has the suddenness of his radicalization been appreciated".[187]

Nadel's 2010 Pound in Context is a contextual literary approach to Pound scholarship. Pound's life, "the social, political, historical, and literary developments of his period", is fully investigated, which, according to Nadel is "the grid for reading Pound's poetry".[188] In 2012 Matthew Feldman wrote that the more than 1,500 documents in the "Pound files" held by the FBI have been ignored by scholars, and almost certainly contain evidence that "Pound was politically cannier, was more bureaucratically involved with Italian Fascism, and was more involved with Mussolini's regime than has been posited".[189]

LegacyPound helped advance the careers of some of the best-known modernist writers of the early 20th century. In addition to Eliot, Joyce, Lewis, Frost, Williams, Hemingway and Conrad Aiken, he befriended and helped Marianne Moore, Louis Zukofsky, Jacob Epstein, Basil Bunting, E. E. Cummings, Margaret Anderson, George Oppen and Charles Olson.[190] Hugh Witemeyer argues that the Imagist movement was the most important in 20th-century English-language poetry because it affected all the leading poets of Pound's generation and the two generations after him.[191] In 1917, Carl Sandburg wrote in Poetry: "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know, ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned."[192]

I have tried to write Paradise

Do not move

Let the wind speak.

that is paradise.

Let the Gods forgive what I

have made

Let those I love try to forgive

what I have made.

— Canto 120[193][194]

The outrage after Pound's wartime collaboration with Mussolini's regime was so deep that the imagined method of his execution dominated the discussion. Arthur Miller considered him worse than Hitler: "In his wildest moments of human vilification Hitler never approached our Ezra ... he knew all America's weaknesses and he played them as expertly as Goebbels ever did." The response went so far as to denounce all modernists as fascists, and it was only in the 1980s that critics began a re-evaluation. Macha Rosenthal wrote that it was "as if all the beautiful vitality and all the brilliant rottenness of our heritage in its luxuriant variety were both at once made manifest" in Ezra Pound.[195]

Pound's antisemitism has soured evaluation of his poetry. Pound scholar Wendy Stallard Flory writes that separating the poetry from the antisemitism is perceived as apologetic. She believes the positioning of Pound as "National Monster" and "designated fascist intellectual" made him a stand-in for the silent majority in Germany, occupied France and Belgium, as well as Britain and the United States, who, she argues, made the Holocaust possible by aiding or standing by.[196]

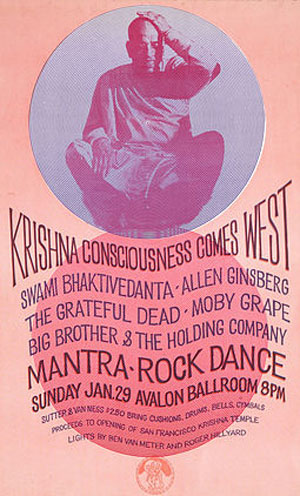

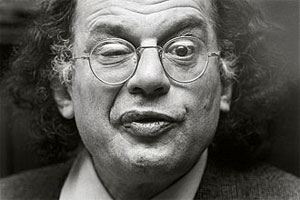

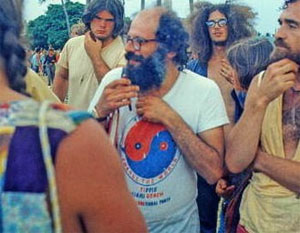

Later in his life, Pound analyzed what he judged to be his own failings as a writer attributable to his adherence to ideological fallacies.[197] Allen Ginsberg states that, in a private conversation in 1967, Pound told the young poet, "my poems don't make sense." He went on to say that he "was not a lunatic, but a moron", and to characterize his writing as "stupid and ignorant", "a mess". Ginsberg reassured Pound that he "had shown us the way", but Pound refused to be mollified:

'Any good I've done has been spoiled by bad intentions—the preoccupation with irrelevant and stupid things,' [he] replied. Then very slowly, with emphasis, surely conscious of Ginsberg's being Jewish: 'But the worst mistake I made was that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-semitism.'[197][198]

Works• 1908 A Lume Spento. Privately printed by A. Antonini, Venice, (poems).

• 1908 A Quinzaine for This Yule. Pollock, London; and Elkin Mathews, London, (poems).

• 1909 Personae. Elkin Mathews, London, (poems).

• 1909 Exultations. Elkin Mathews, London, (poems).

• 1910 The Spirit of Romance. Dent, London, (prose).

• 1910 Provenca. Small, Maynard, Boston, (poems).

• 1911 Canzoni. Elkin Mathews, London, (poems)

• 1912 The Sonnets and Ballate of Guido Cavalcanti Small, Maynard, Boston, (cheaper edition destroyed by fire, Swift & Co, London; translations)

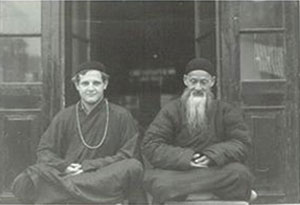

• 1912 Ripostes. S. Swift, London, (poems; first announcement of Imagism)

• 1915 Cathay. Elkin Mathews, (poems; translations)

• 1916 Gaudier-Brzeska. A Memoir. John Lane, London, (prose).[199]

• 1916 Certain Noble Plays of Japan: From the Manuscripts of Ernest Fenollosa, chosen and finished by Ezra Pound, with an introduction by William Butler Yeats.

• 1916 Ernest Fenollosa, Ezra Pound: "Noh", or, Accomplishment: A Study of the Classical Stage of Japan. Macmillan, London,

• 1916 Lustra. Elkin Mathews, London, (poems).

• 1917 Twelve Dialogues of Fontenelle, (translations)

• 1917 Lustra Knopf, New York. (poems). With a version of the first Three Cantos(Poetry, vol. 10, nos. 3, June 1917, 4, July 1917, 5, August 1917).

• 1918: Pavannes and Divisions. Knopf, New York. prose

• 1918 Quia Pauper Amavi. Egoist Press, London. poems

• 1919 The Fourth Canto. Ovid Press, London

• 1920 Hugh Selwyn Mauberley. Ovid Press, London.

• 1920 Umbra. Elkin Mathews, London, (poems and translations)

• 1920 Instigations of Ezra Pound: Together with an Essay on the Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry, by Ernest Fenollosa. Boni & Liveright, (prose).

• 1921 Poems, 1918–1921. Boni & Liveright, New York

• 1922 Remy de Gourmount: The Natural Philosophy of Love. Boni & Liveright, New York, (translation)

• 1923 Indiscretions, or, Une revue des deux mondes. Three Mountains Press, Paris.

• 1924 Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony. Paris, (essays). As: William Atheling.

• 1925 A Draft of XVI Cantos. Three Mountains Press, Paris. The first collection of The Cantos.

• 1926 Personae: The Collected Poems of Ezra Pound. Boni & Liveright, New York

• 1928 A Draft of the Cantos 17–27. John Rodker, London.

• 1928 Selected Poems, edited and with an introduction by T. S. Eliot. Faber & Gwyer, London

• 1928 Confucius: Ta Hio: The Great Learning, newly rendered into the American language. University of Washington Bookstore (Glenn Hughes), (translation)

• 1930 A Draft of XXX Cantos. Nancy Cunard's Hours Press, Paris.

• 1930 Imaginary Letters. Black Sun Press, Paris. Eight essays from the Little Review, 1917–18.

• 1931 How to Read. Harmsworth, (essays)

• 1932 Guido Cavalcanti Rime. Edizioni Marsano, Genoa, (translations)

• 1933 ABC of Economics. Faber, London, (essays)

• 1934 Eleven New Cantos: XXXI-XLI. Farrar & Rinehart, New York, (poems)

• 1934 Homage to Sextus Propertius. Faber, London (poems)

• 1934 ABC of Reading. Yale University Press, (essays)

• 1935 Alfred Venison's Poems: Social Credit Themes by the Poet of Titchfield Street. Stanley Nott, Pamphlets on the New Economics, No. 9, London, (essays)

• 1935 Jefferson and/or Mussolini. Stanley Nott, London, Liveright, 1936 (essays)

• 1935 Make It New. London, (essays)

• 1935 Social Credit. An Impact. London, (essays). Repr.: Peter Russell, Money Pamphlets by Pound, no. 5, London 1951.

• 1936 Ernest Fenollosa: The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Stanley Nott, London 1936. An Ars Poetica With Foreword and Notes by Ezra Pound.

• 1937 The Fifth Decade of Cantos. Farrar & Rinehart, New York, poems

• 1937 Polite Essays. Faber, London, (essays)

• 1937 Confucius: Digest of the Analects, edited and published by Giovanni Scheiwiller, (translations)

• 1938 Culture. New Directions. New edition: Guide to Kulchur, New Directions, 1952

• 1939 What Is Money For?. Greater Britain Publications, (essays). Money Pamphlets by Pound, no. 3, Peter Russell, London

• 1940 Cantos LXII-LXXI. New Directions, New York, (John Adams Cantos 62–71).

• 1942 Carta da Visita di Ezra Pound. Edizioni di lettere d'oggi. Rome. English translation, by John Drummond: A Visiting Card, Money Pamphlets by Pound, no. 4, Peter Russell, London 1952, (essays).

• 1944 L'America, Roosevelt e le cause della guerra presente. Casa editrice della edizioni popolari, Venice. English translation, by John Drummond: America, Roosevelt and the Causes of the Present War, Money Pamphlets by Pound, no. 6, Peter Russell, London 1951

• 1944 Introduzione alla Natura Economica degli S.U.A.. Casa editrice della edizioni popolari. Venice. English translation An Introduction to the Economic Nature of the United States, by Carmine Amore. Repr.: Peter Russell, Money Pamphlets by Pound, London 1950 (essay)

• 1944 Orientamini. Casa editrice dalla edizioni popolari. Venice (prose)

• 1944 Oro et lavoro: alla memoria di Aurelio Baisi. Moderna, Rapallo. English translation: Gold and Work, Money Pamphlets by Pound, no. 2, Peter Russell, London 1952 (essays)

• 1948 If This Be Treason. Siena: privately printed for Olga Rudge by Tip Nuova (original drafts of six of Pound's Rome radio broadcasts)

• 1948 The Pisan Cantos. New Directions, (Cantos 74–84)

• 1948 The Cantos of Ezra Pound (includes The Pisan Cantos). New Directions, poems

• 1949 Elektra (started in 1949, first performed 1987), a play by Ezra Pound and Rudd Fleming

• 1950 Seventy Cantos. Faber, London.

• 1950 Patria Mia. R. F. Seymour, Chicago Reworked New Age articles, 1912, '13 (Orage)

• 1951 Confucius: The Great Digest; The Unwobbling Pivot. New Directions (translation)

• 1951 Confucius: Analects (John) Kaspar & (David) Horton, Square $ Series, New York, (translation)

• 1954 The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius. Harvard University Press (translations)

• 1954 Lavoro ed Usura. All'insegna del pesce d'oro. Milan (essays)

• 1955 Section: Rock-Drill, 85–95 de los Cantares. All'insegna del pesce d'oro, Milan, (poems)

• 1956 Sophocles: The Women of Trachis. A Version by Ezra Pound. Neville Spearman, London, (translation)

• 1957 Brancusi. Milan (essay)

• 1959 Thrones: 96–109 de los Cantares. New Directions, (poems)

• 1968 Drafts and Fragments: Cantos CX-CXVII. New Directions, (poems).[200]

Notes1. ^ Ernest Hemingway wrote in 1925: "[W]e have Pound the major poet devoting, say, one fifth of his time to poetry. With the rest of his time he tries to advance the fortunes, both material and artistic, of his friends. He defends them when they are attacked, he gets them into magazines and out of jail. He loans them money. He sells their pictures. He arranges concerts for them. He writes articles about them. He introduces them to wealthy women. He gets publishers to take their books. He sits up all night with them when they claim to be dying and he witnesses their wills. He advances them hospital expenses and dissuades them from suicide. And in the end a few of them refrain from knifing him at the first opportunity."[1]

2. ^ Stock (1970): "In a letter written in October 1966 Mrs Pound recalled the period in these words: 'E.P. was in Rome when it was taken and he walked out (in a pair of Degli Uberti's heavy boots, many years later restored to owner) along the only road going north not infested by troops—spent a night in the open and with some peasants—got to a junction where there was a train going north with a herd of the dismantled Italian army ...' In an article published in 1966 his daughter said that during the long journey he slept in farms, in dormitories, and in the open, receiving food from kindly women on the way. Altogether Pound travelled more than 450 miles, arriving at Gais, his daughter said, 'one late afternoon, exhausted, his feet all blisters'."[118]

3. ^ The Associated Press reported the list of judges as Conrad Aiken, W. H. Auden, Louise Bogan, Katherine Garrison Chapin, T. S. Eliot, Paul Green, Robert Lowell, Katherine Anne Porter, Karl Shapiro, Allen Tate, Willard Thorp and Robert Penn Warren. Also on the list were Leonie Adams, the Library of Congress's poetry consultant, and Theodore Spencer, who died on 18 January 1949, just before the award was announced.[128]

4. ^ "At their [the committee's first] meeting [in November 1948], and to no one's great surprise, given [Allen] Tate's behind-the-scenes maneuverings and the intimidating presence of recent Nobel Laureate T. S. Eliot, The Pisan Cantos emerged as the major contender ..."[129]

See also• Ezra Pound portal

References

Citations1. Hemingway, "Homage to Ezra", This Quarter, 1, Spring 1925, 221–225, in Hemingway (2006), 5–6

2. The Pisan Cantos (80.665–67), Sieburth (2003), xiii

3. "Books: Unpegged Pound", Time, 20 March 1933; Hemingway (2006), 25, from The Cantos of Ezra Pound: Some Testimonies by Ernest Hemingway, Ford Madox Ford, T. S. Eliot, Hugh Walpole, Archibald McLeish, James Joyce, and Others, Farrar & Rinehart, March 1933

4. Moody (2007), 4; Ridler, Keith. "Poet's Idaho home is reborn", Associated Press, 25 May 2008; for Idaho Territory, see Wilson (2014), 14.

5. Tytell (1987), 11

6. Moody (2007), xiii–13

7. Cockram (2005), 238

8. Moody (2007), xiii

9. Rachewiltz, Moody and Moody (2011), x

10. Moody (2007), 8–9

11. Moody (2007), 14; for Cheltenham Township High School, see McDonald (2005), 91, and Stock (1970), 11

12. Nadel (2004), 18; Barnstone (1998), 202

13. Doolittle (1979), 67–68; Hilda's Book is in the Houghton Library at Harvard; see "Poems and Translations", Library of America.

14. Nadel (2004), 31

15. Tytell (1987), 24–28; for dedication of Personae, see Nadel (1999), xviii

16. Moody (2007), 18–25

17. Stock (1964), 6

18. Moody (2007), 19, 27–28

19. Moody (2007), 28–29

20. Moody (2007), 29–31

21. Stock (1970), 37.

22. Moody (2007), 58–59

23. Moody (2007), 60–62; Wilhelm (1985), 177; Carpenter (1988), 80; Nadel (2004), 30

24. Moody (2007), 62, 63; for the bakery, Tytell (1987), 35

25. Eliot (1917), 5

26. Zinnes (1980), xi; for information about Brooke Smith, see Carpenter (1988), 91, 95

27. Knapp (1979), 25–27

28. Stock (1970), 53–54

29. Wilhelm (2008), 4; Pound (2003), 80, lines 334–336; also see Campbell, James. "Home from home", The Guardian, 17 May 2008.

30. Wilhelm (2008), 5–11

31. Wilhelm (2008), 7

32. Ford 1999, 277.

33. Hemingway (2006), 6

34. Tytell (1987), 46

35. For the money from Cravens, see Moody (2007), 124–125; for the speculation that they were lovers, see Carpenter (1988), 155; Dennis (1999), 264; Pound, Omar (1988), 66

36. Moody (2007), 91; Elek, Jon. "Personae", The Literary Encyclopedia, 8 April 2004.

37. Moody (2007), 93

38. Wilson, Peter. "Exultations", The Literary Encyclopedia, 20 April 2004.

39. Moody (2007), 180

40. Stock (1970), 70, 81–89

41. Wilhelm (2008), 62–65

42. Montgomery, Paul L. "Ezra Pound: A Man of Contradictions", The New York Times, 2 November 1972

43. Tytell (1987), 59–62

44. Stock (1970), 95

45. Elek, Jon. "Canzoni", The Literary Encyclopedia, 8 March 2005. Orage was referred to in The Cantos (Possum refers to T. S. Eliot): "But the lot of 'em, / Yeats, Possum and Wyndham / had no ground beneath 'em. / Orage had." See Wilhelm (2008), 83, citing Canto 98/685.

46. Arrowsmith (2011), 103–164; also see Arrowsmith (2011), 27–42, 118, and Dennis (2000), 101

47. Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard (March 2012). "Cosmopolitanism and Modernism" (video of a lecture discussing the importance of Japanese culture to Pound's early poetry), London University School of Advanced Study.

48. Witemeyer (1961), 112.

49. Venuti (1979), 88; Knapp (1979), 54

50. Moody (2007), 180, 222

51. Pound, Ezra. "A Retrospect", in T. S. Eliot. (1968). Literary Essays of Ezra Pound. New York: New Directions Publishing (first published 1918), 3–5.

52. Witemeyer (1969), 34; for its description as theclassic Imagist poem, see Witemeyer (1999), 49

53. Alexander (1979), 62

54. Pound, Ezra, Ripostes, Stephen Swift & Co Ltd, London, 1912; Pound (1918), 4

55. For submission and publication dates, see Pound, Ezra. Poems and translations, Library of America, (2003), 1239

56. For the original text of The Seafarer, see "The Seafarer", Anglo-Saxons.net; for Pound's interpretation, see Pound, Ezra. "The Seafarer", Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto.

57. Sieburth (2010), xv

58. Moody (2007), 239

59. The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry: A Critical Edition (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008).

60. Alexander (1979), 95

61. Yip, Wai-lim. Ezra Pound's Cathay. Princeton University Press, 1969, cited in Alexander (1979), 99

62. Kern, Robert (1996). Orientalism, Modernism, and the American Poem. Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–189. ISBN 978-0-521-49613-1.

63. "The Fenollosa Papers" in Stock (1965), 177–179

64. Graves, from "These Be Your Gods, O Israel" (138–139)

65. Yao (2010), 36–39

66. Stock (1970), 143–147; Tytell (1987), 97

67. Moody (2007), 240; Longenbach (1988); Longenbach, James. "The Odd Couple: Pound and Yeats Together", The New York Times, 10 January 1988.

68. Moody (2007), 246–249

69. Moody (2007), 230, 256

70. Stock (1970), 159

71. Campbell, James. "Home from home", The Guardian, 17 May 2008.

72. Moody (2007), 222–225

73. Aiken (1965), 4–5

74. Mertens, Richard. "Letter by letter", University of Chicago Magazine, April 2001.

75. Moody (2007), 306–307

76. Moody (2007), 330, 334

77. Moody (2007), 342

78. Stock (1970), 174, 180–182

79. Moody (2007), 334–335

80. Kenner (1971), 286

81. Pound, Ezra. "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley", Project Gutenberg, 18 November 2007.

82. Adams (2005), 149; Leavis (1932), 134, 150.

83. Moody (2007), 394–396

84. Witemeyer (1969), 25; Orage (1921), 201

85. Orage (1921), 199–200; Stock (1970), 235; Moody (2007), 410

86. Wilhelm (2008), 287.

87. Meyers (1985), 70–74

88. Bornstein (1999), 33–34

89. Carpenter (1988), 430–431, 448

90. Tytell (1987), 180; Wilhelm (2008), 251

91. For his operas, see Kenner (1973), 390; for his pieces for violin, see Stock (1970), 252–256

92. Tytell (1987), 191–193

93. Baker (1981), 127

94. Tytell (1987), 225

95. Tytell (1987), 198

96. Wilhelm (1994), 13–15

97. Carpenter (1988), 450–451

98. Carpenter (1988), 452–453

99. For the house in Venice, see Tytell (1987), 198, and Mamoli Zorzi (2007), 15, 23; for Mary's memoir, see de Rachewiltz (1971), 1

100. Wilhelm (1994), 22–24

101. Nadel (1999), xxi–xxiii

102. Tytell (1987), 215

103. Terrell (1980), vii

104. Bush (1976), xiii–xv

105. Preda (2005), 90

106. Tytell (1987), 228–232

107. Tytell (1987), 250–253

108. Tytell (1987), 254

109. Tytell (1987), 253–265

110. "Selected World War II Broadcasts", Modern American Poetry, citing "Ezra Pound Speaking": Radio Speeches of World War II. Ed. Leonard W. Doob. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1978.

111. Tytell (1987), 260

112. Tytell (1987), 264–266

113. Tytell (1987), 268–270

114. Gill (2005), 115–116

115. Sieburth (2003b), xiv

116. Gery (2010), 222

117. Tytell (1987), 262

118. Stock (1970), 401; also see Tytell (1987), 264–273

119. Sieburth (2003), ix–xiv

120. Sieburth (2003), xxxvi

121. Sieburth Stock (1970), 408; Sieburth (2003b), xi

122. Stock (1970), 408

123. Kimpel (1981), 470–474

124. Tytell (1987), 289–297, 304–305

125. For Cornell's efforts, see "Julien Cornell, 83, The Defense Lawyer In Ezra Pound Case", The New York Times, 7 December 1994.

126. Mitgang, Herbert. "Researchers dispute Ezra Pound's 'insanity'", The New York Times, 31 October 1981; also see Kutler, Stanley I. (1983). American Inquisition: Justice and Injustice in the Cold War. Hill & Wang.

127. Tytell (1987), 293, 302–303; Tytell cites MacLeish, Archibald. Riders on the Earth, Houghton Mifflin, 1978, 120; Winnick, R. H. (ed.) Letters of Archibald MacLeish, 1907 to 1982. Houghton Mifflin, 1983, and in particular a letter from MacLeish to Milton Eisenhower, which is in the Library of Congress. For more details of who supported and opposed, see McGuire (1988).

128. "Pound, in Mental Clinic, Wins Prize for Poetry Penned in Treason Cell", Associated Press, 19 February 1949.

129. Sieburth (2003), xxxviii–xxxix

130. "Canto Controversy" Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 22 August 1949.

131. Hillyer, Robert. "Treason's Strange Fruit" and "Poetry's New Priesthood", in The Saturday Review of Literature, 11 and 18 June 1949.

132. McGuire, William. Poetry's Catbird Seat, Library of Congress, 1998.

133. Wilhelm (1994), 286, 306

134. Hickman (2005), 127

135. Tytell (1987), 306–308

136. Stock (1970), 437

137. Reynolds (2000), 303

138. Hemingway, Ernest. "The Art of Fiction", Paris Review, No. 21.

139. "Police Firmness in Nashville", Life magazine, 23 September 1957, 34; Tytell (1987), 308; Webb (2011), 88–89

140. Lewis, Anthony. "U.S. asked to end Pound indictment", The New York Times, 14 April 1958.

141. Tytell (1987), 325–326

142. Arnold, Thurman (1965). Fair Fights and Foul: A Dissenting Lawyer's Life (1 ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. pp. 236–242.

143. "Pound, in Italy, Gives Fascist Salute; Calls United States an 'Insane Asylum'", The New York Times, 10 July 1958.

144. Tytell (1987), 328–332; for the reference to "Canto 113", see Sieburth (2003), xl

145. Tytell (1987), 347; Hall, Donald. "Ezra Pound, The Art of Poetry No. 5", The Paris Review, 28, Summer–Fall 1962.

146. Tytell (1987), 333–336

147. Nadel (2007), 18

148. Tytell (1987), 337–339

149. Tytell (1987), 339; "Ezra Pound Dies in Venice at Age of 87", The New York Times, 2 November 1972.

150. O'Connor (1963), 7, 19

151. Nadel (1999), 1–6; Witmeyer (1999), 47

152. Coats (2009), 87–89

153. Ingham (1999), 236–237

155. Pound (1968), 103

156. Ingham (1999), 244–245

157. Oliver (2011), 87

158. Albright (1999), 60

159. Yao (2010), 34–35

160. Yao (2010), 33–36

161. Alexander (1997), 23–30

162. Xie (1999), 204–212

163. Kenner (1971), 199

164. Nadel (1999), 1–6

165. Beasley (2010), 662

166. Xie (1999), 217

167. Ingham (1999), 240

168. O'Connor (1963), 7

169. Tate (1965), 87

170. Nadel (1999), 8

171. Nicholls (1999), 144

172. Bacigalupo (1999), 188–191

173. Bacigalupo (1999), 203

174. Redman (1999), 258

175. Redman (1999), 255–260

176. Nadel (1999), 10

177. Bacigalupo (1999), 203; Coats (2009), 80, 83

178. Wilson, Edmund (2007). "Ezra Pound's Patchwork", Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s & 30s. Library of America, 44, 45; the essay was first published on 19 April 1922.

179. Beasley (2010), 651

180. Nadel (1999), 12

181. Kenner (1983), 16

182. Alexander (1997), 15–18

183. Nadel (2010b), 162–165

184. Nadel (1999), 13

185. Feldman (2012), 94

186. Coats (2009), 81

187. Surrette (1999) 13

188. Nadel (2010a), 1–6

189. Feldman (2012), 90–91

190. Bornstein (1999), 22–23

191. Witemeyer (1999), 48

192. Eliot (1917), 3

193. Canto 120, the final canto, first published in Threshold, Belfast, and in The Anonym Quarterly, New York, 1969. See Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New Directions Books, 1983, 802

194. There is a debate about the placement of the final canto. See "Late Cantos LXXII–CXVII" Bush (1999), 132; also see Stoicheff, Peter. The Hall of Mirrors: Drafts & Fragments and the End of Ezra Pound's Cantos. University of Michigan Press, 1995, 66

195. For Arthur Miller's quote, see Torrey (1984), 200. For Rosenthal, see her A Primer of Ezra Pound. Macmillan, 1960, 2

196. Flory (1999), 285–286, 294–300

197. Carpenter (1988), 898–899

198. Kashner, Sam (2005). When I Was Cool. New York: HarperCollins Perennial. p. 86. ISBN 006000567-X. Allen explained how he tried to deal with anti-Semitic remarks. He said that he even got Ezra Pound to "take it back," to admit that it was a dumb, suburban prejudice.

199. Translated into French by Margaret Tunstill and Claude Minière Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Tristram éd., Auch, France, 1992

200. Ackroyd, Peter. (1980). Ezra Pound. Thames and Hudson Ltd., 121. For early publications, see Eliot, T. S. (1917). Ezra Pound, His Metric and Poetry. Alfred A. Knopf, 1917, 29–31

Bibliography• Adams, Stephen J. (2005). "Hugh Selwyn Mauberley", in Demetres P. Tryphonopoulos and Stephen Adams (eds.). The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-30448-4

• Aiken, Conrad. (1965). "Ezra Pound: 1914" in Stock, Noel (ed.). Ezra Pound: Perspectives. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

• Albright. Daniel. (1999). "Early Cantos: I – XLI", in Ira Nadel (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Alexander, Michael. (1997). "Ezra Pound as Translator". Translation and Literature. Volume 6, No. 1.

• Alexander, Michael. (1979). The Poetic Achievement of Ezra Pound. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0981-9

• Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard. (2011). Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9

• Baker, Carlos. (1981). Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917–1961. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-16765-7

• Bacigalupo, Massimo. (1999.) "Pound as Critic", in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Barnstone, Aliki (1998). "A Note on H.D.'s Life", in H.D. Trilogy. New York: New Directions Publishing.

• Beasley, Rebecca. (2010). "Pound's New Criticism". Textual Practice. Volume 24, No. 4.

• Bornstein, George. (1985). "Ezra Pound Among the Poets", in Ira B. Nadel (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Casillo, Robert. (1988). The Genealogy of Demons: Anti-Semitism, Fascism, and the Myths of Ezra Pound. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1988.

• Carpenter, Humphrey. (1988). A Serious Character: The Life of Ezra Pound. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-41678-5

• Coats, Jason M. (2009). ""Part of the War Waste": Pound, Imagism, and Rhetorical Excess". Twentieth Century Literature, Volume 55, No. 1.

• Cockram, Patricia. (2005). "Pound, Isabel Weston", in Demetres P. Tryphonopoulos and Stephen Adams (eds). The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2005. ISBN 978-0-313-30448-4

• Dennis, Helen May. (1999). "Pound, Women and Gender". in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Dennis, Helen May. (2000). Ezra Pound and Poetic Influence. Internationale Forschungen zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft, Volume 51. ISBN 978-90-420-1523-4

• Doolittle, Hilda. (1979). End to Torment. New York: New Directions Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8112-0720-1

• Eliot, T. S. (1917). Ezra Pound: His Metric and his Poetry. New York: Alfred A. Knopf

• Feldman, Matthew. (2012). "The 'Pound Case' in Historical Perspective: An Archival Overview". Journal of Modern Literature, Volume 35, No. 2.

• Ford, Ford Madox (1999). Return to Yesterday. Manchester: Carcanet Press (first published 1931). ISBN 978-1-8575-4397-1

• Flory, Wendy. (1999). "Pound and Antisemitism", in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Gery, John. (2010). "Venice". in Ira Nadel (ed). Ezra Pound in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51507-8

• Gill, Jonathan. (2005). "Ezra Pound Speaking: Radio Speeches on World War II", in Demetres P. Tryphonopoulos and Stephen Adams (eds). The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-30448-4

• Hall, Donald. (1992). Their Ancient Glittering Eyes: Remembering Poets and More Poets. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-89919-979-5

• Haller, Evelyn. (2005). "Mosley, Sir Oswald" in Demetres P. Tryphonopoulos and Stephen Adams (eds). The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-30448-4

• Hemingway, Ernest. Bruccoli, Matthew and Baughman, Judith (eds.). (2006). "Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-599-9

• Hickman, Miranda B. (2005). The Geometry of Modernism: The Vorticist Idiom in Lewis, Pound, H.D., and Yeats. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70943-0

• Ingham, Michael. (1999). "Pound and Music", in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Kenner, Hugh. (1983 ed.) The Poetry of Ezra Pound. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press; first published 1951. ISBN 978-0-8032-7756-4

• Kenner, Hugh. (1973). The Pound Era. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02427-4

• Kimpel, Ben D. and Eaves, Duncan. (1981). "More on Pound's Prison Experience". American Literature. Volume 53, No. 1.

• Knapp, James F. (1979). Ezra Pound. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7286-9

• Leavis, F. R. (1932). New Bearings in English Poetry. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-571-24335-8

• Longenbach, James (1988). Stone Cottage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• McGuire, William. (1988). Poetry's Catbird Seat. Washington: Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-16-004004-7

• Mamoli Zorzi, Rosella et al. (2007). In Venice and in the Veneto with Ezra Pound. Venice: Supernova. ISBN 978-88-88548-79-1

• Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-42126-0

• Moody, A. David (2007). Ezra Pound: Poet: A Portrait of the Man and His Work, Volume I, The Young Genius 1885–1920. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957146-8

• Nadel, Ira. (1999). "Introduction", in Ira Nadel (ed).Introduction: Understanding Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Nadel, Ira. (2004). Ezra Pound: A Literary Life. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-58257-2

• Nadel, Ira. (2010a). "Introduction". in Ira Nadel (ed). Ezra Pound in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51507-8

• Nadel, Ira. (2010b). "The Lives of Pound". in Ira Nadel (ed). Ezra Pound in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51507-8

• Nicholls, Peter. (1999). "Beyond the Cantos: Ezra Pound and recent American poetry". in Ira Nadel (ed).The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• O'Connor, William Van. (1963). Ezra Pound. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

• Orage, A. R. (1921). "A. R. Orage on Pound's Departure from London". in Eric Homberger (ed.). Ezra Pound. Routledge (first published as R.H.C., "Readers and Writers", New Age, 31 January 1921, xxviii, 126–127).

• Pound, Ezra. (1926). Personæ. New York: New Directions. 1990 edition. ISBN 978-0-8112-1120-8

• Pound, Ezra. (2005 ed). The Spirit of Romance. New York: New Directions ISBN 978-0-8112-1646-3

• Pound, Ezra. (2006). "Horace" (edited by Caterina Ricciardi). Rimini (Italy): Raffaelli. ISBN 978-88-89642-78-8

• Pound, Ezra. (2006). "The Fifth Decade of Cantos " (translated into Italian by Mary de Rachewiltz). Rimini (Italy): Raffaelli. ISBN 978-88-89642-19-1

• Pound, Omar, ed., (1988). Ezra Pound and Margaret Cravens: A Tragic Friendship, 1910–1912. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0862-1

• Preda, Roxana. (2005), in Demetres P. Tryphonopoulos and Stephen Adams (eds). The Ezra Pound Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-30448-4

• Rachewiltz, Mary de. (1971). Discretions: A memoir by Ezra Pound's daughter. New York: New Directions.ISBN 978-0-8112-1647-0

• Rachewiltz, Mary de; Moody, A. David; and Moody, Joanna (2011). Ezra Pound to His Parents: Letters 1895–1929. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958439-0

• Redman, Tim. (1991). Ezra Pound and Italian Fascism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37305-0

• Redman, Tim. (1999). "Pound's politics and economics", in Ira Nadel (ed). Introduction: Understanding Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Reynolds, Michael (1999). Hemingway: The Final Years. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32047-3

• Sieburth, Richard. (2003b). The Pisan Cantos. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1558-9

• Sieburth, Richard. (2003a). Poems and Translation. New York: The Library of America. ISBN 978-1-931082-42-6

• Sieburth, Richard. (2010). New Selected Poems and Translation. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1733-0

• Stark, Robert. (2001). "Pound Among the Nightingales – From the Troubadours to a Cantible Modernism". Journal of Modern Literature. Volume 32, No. 2.

• Stock, Noel. (1964). Poet in Exile. Manchester: University of Manchester.

• Stock, Noel. (1970). The Life of Ezra Pound. New York: Pantheon Books.

• Surrette, Leon. (1999). Pound in Purgatory: From Economic Radicalism to Anti-Semitism. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02498-6

• Tate, Allen. (1965). "Ezra Pound and the Bollingen Prize", in Noel Stock (ed.). Ezra Pound Perspectives. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

• Terrell, Carroll F. (1980). A Companion to The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03687-1

• Torrey, Edwin Fuller. (1984). The Roots of Treason and the Secrets of St Elizabeths, New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-064983-5

• Tytell, John. (1987). Ezra Pound: The Solitary Volcano. New York: Anchor Press. ISBN 978-0-385-19694-9

• Venuti, Lawrence. (2004). The Translation Studies Reader, London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31919-5

• Webb, Clive. (2011). Rabble Rousers: The American Far Right in the Civil Rights Era. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

• Wilhelm, J. (1985). The American Roots of Ezra Pound. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. ISBN 978-0-8240-7500-2

• Wilhelm, James J. (1994). Ezra Pound: The Tragic Years 1925–1972. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-2-7101-0827-6

• Wilhelm, James J. (2008). Ezra Pound in London and Paris, 1908–1925. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02798-2

• Wilson, Peter (2014) [1997]. A Preface to Ezra Pound. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-25867-9

• Witemeyer, Hugh (ed). (1996). Pound/Williams: Selected letters of Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1301-1

• Witemeyer, Hugh. (1999). "Early Poetry 1908–1920", in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Witemeyer, Hugh (ed.). (1969). The Poetry of Ezra Pound. Berkeley: University of California Press.

• Yao, Steven G. (2010). "Translation", Ira B. Nadel (editor), in Ezra Pound in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51507-8

• Xie, Ming. (1999). "Pound as Translator". in Ira Nadel (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64920-9

• Zinnes, Harriet (ed). (1980). Ezra Pound and the Visual Arts. New York: New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-0772-0

External links• The Ezra Pound Society

• Ezra Pound at Curlie

• Works by Ezra Pound at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Ezra Pound at Internet Archive

• Works by Ezra Pound at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• "Ezra Pound in his Time and Beyond", University of Delaware Library.

• Ezra Pound papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

• Still photographs of Ezra Pound, Beinecke Library

• Ezra Pound collection at University of Victoria, Special Collections

• Frequently requested records: Ezra Pound, United States Department of Justice.

• Records of Ezra Pound are held by Simon Fraser University's Special Collections and Rare Books

Audio/video

• Ezra Pound recordings, University of Pennsylvania.

• "The Four Steps", Pound discussing bureaucracy, BBC Home Service, 21 June 1958.

• Hammer, Langdon. Lecture on Ezra Pound, Yale University, February 2007.