Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia: A Tribute: From the Tribune September 9, 1998

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A broad-minded liberal

A broad-minded liberal

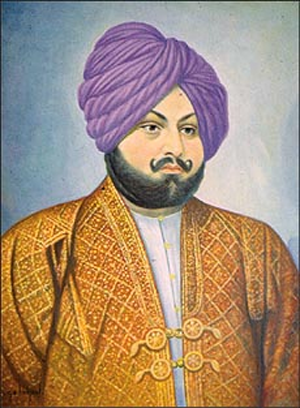

by Madan GopalSARDAR Dyal Singh Majithia was the son of a family that had played a very important part in the history of the Sikh state founded by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. For three generations the family had provided generals to the Maharaja's forces, and Dyal Singh's father was the head of the kingdom's ordnance. His uncle, Gujar Singh, who had been deputed by Maharaja Ranjit to go to Calcutta on a diplomatic mission, was accompanied by 200 armed men specially chosen by the Maharaja. And when Dyal Singh's father, Lehna Singh, left Lahore for a pilgrimage, his adversaries at the darbar at Lahore said that he too had gone with an escort of 200 people and taken gold worth a crore of rupees. Lehna Singh went to different pilgrimage centres and finally bought an estate in Kashi (Benaras).

One yardstick of the importance in society of the family in the British times was the placement in the list of protocol. And so eminent was Dyal Singh's family that when the Viceregal darbar was held in Lahore in 1864, of the 603 people invited, Dyal Singh, then aged 16, was allotted the 55th seat, his uncle Ranjodh Singh being 103rd.

While some members of the erstwhile ruling class lived a life of ease and indulgence, hankered after titles and jagirs, some others took up such jobs as that of tehsildar or extra-assistant commissioner, Dyal Singh decided to carve out a career for himself. Tall, well-built and handsome with refined tastes and aristocratic bearing, he became a shrewd business man dealing in real estate and precious stones and jewellery.

The areas outside the walled city of Lahore had barracks for the British soldiers. Once the British decided that a cantonment should be built in Mian Mir, the barracks were to be pulled down and the plots auctioned. Dyal Singh's agents bid for the plots whereupon he constructed buildings to be rented out to high British civilians. When he died in 1898 he owned 26 prestigious properties, including Dyal Singh Mansion of 54 residential units on The Mall, scores of lawyers, chambers on Fane Road, the exchange building which was later sold to Ganga Ram Hospital, and a property in Karachi which was sold after his death and the earning invested in the purchase of land on the road to Mian Mir, where today stands the new campus of Panjab University. Most of the buildings, plots of land and villages in Lahore, Amritsar and Gurdaspur districts were bequeathed to the trusts that set up Dyal Singh College and Dyal Singh Library.

His other business activity concerned the purchase and resale of precious jewellery. With his deep knowledge of the history of the Sikh kingdom and the riches of the once important and wealthy families now in dire straits, he sent agents to buy these out for him. He was a connoisseur of precious stones and told his friends how lucrative this business was.

From the real estate created by him and the trade in precious stones he earned a huge fortune. The assets created by him and bequeathed in a will drawn up in 1895 were worth Rs 30 lakh, Rs 7 lakh more than the assets bequeathed in 1893 by Sir Dorabji Tata to the House of Tatas.

A great advocate of Western education, he was largely responsible for the setting up of Panjab University. He made a handsome donation to Sir Syed Ahmed's Anjuman-i-Islamia, and set up a Union Academy at Lahore, the nucleus of Dyal Singh School and College.

Dyal Singh was a great philanthropist. He gave much in charity. It is significant that he decided on the amount to be given away to charities in advance, depending upon the earnings in the previous month. And this amount, once fixed, was not to be exceeded. Also if he promised to give a certain amount in the following month this was as good as given, there seldom being any delay in disbursement. He was so meticulous that once when he detected a mistake of a few pies in the total he told the person sending it about the carelessness and warned if a mistake was made again, he would stop all donations so long as the latter was in position.

Dyal Singh lived like a prince. He had the hobbies and failings of the class that he belonged to. His luncheon was a prolonged affair, sometimes continuing for more than a couple of hours. As per the practice, while he and the guests ate, there was some show of entertainment or music or tricks by a madari, or some other activity of this kind. He was a patron of wrestling and a keen kite-flyer. Chess was also his favourite game. He was a great player, and, with plenty of money to spend, he would invite well-known chess players even from Delhi and paid hefty fees.

Dyal Singh was fond of classical music and himself played sitar. A man of great refinement, he was also a poet and wrote in Urdu under the pseudonym "Mashriq". Three of his "Sihafis" are kept in the British Library in London. He wrote flowery prose too and was proud of it. In his ancestral house in Amritsar, he built special rooms for guests.

Dyal Singh was an unorthodox person. He had Muslim and Christian cooks. At his dining table sat Sikhs, Hindus, Christians and Parsis. The wine dealers' bill for himself and guests was substantial.

A scion of the family that had held charge of the affairs of the Golden Temple for decades, Dyal Singh returned from Kashi to Majitha. Instructed by a British governess and then educated at the Christian Mission School at Amritsar, he had an inquisitive mind. He knew more about Christ and Christianity than even the pastors. With a religious bent of mind, he studied the Gita with the help of a Sanskrit teacher from Ferozepur, and studied the Quran too. At this time, there was an exchange of letters between a Sunni Muslim converted to Christianity and a Muslim divine in Lucknow. These letters related to the basic theological issues. Dyal Singh edited the letters and brought out a 115-page booklet, "Naghma-a-Tamboori". His house was the venue of serious discussion and debates on such issues, and for these he would forego even his evening outings. Cool and composed, he seldom lost his temper even with the large retinue of domestic servants at Lahore and Amritsar.

Dyal Singh's first wife died in 1876 or so. His plans to marry a Bengali Brahmo woman did not bear fruit, and he was persuaded to marry Rani Bhagwan Kaur. This did not prove to be a happy union. She observed pardah, and was not normally seen. In fact, Dyal Singh maintained three establishments, one each in Lahore, Amritsar and Karachi. As the work that he had chosen for himself required him to stay in Lahore, he was in Amritsar only for brief periods. He had no issue. He was the most important Brahmo leader of Punjab and the principal financier of the Brahmo Samaj. He was made a trustee of the Brahmo Samaj Mandir in Calcutta.

He was accessible to all those who were seekers after truth. He rendered financial assistance to the needy, irrespective of their religious beliefs.

The only other important Punjabi Brahmo leader was Shiv Narayan Agnihotri, who later left the ranks and set up a rival organisation called the Dev Samaj. Once he approached Dyal Singh for help to build a temple. Dyal Singh obliged him by supplying bricks to the founder of a movement that was antagonistic in nature compared to the one to which he belonged. This gesture was unusual but, then, Dyal Singh himself was, in some ways, an unusually generous, broad-minded and liberal person.Top

***

Dyal Singh Majithia: A genius with foresight

by B. K. NehruSARDAR Dyal Singh Majithia was undoubtedly one of the most remarkable pioneers who led India out of the darkness of ignorance to the enlightenment of modernity. He did for North India what Raja Rammohun Roy had done for Bengal three quarters of a century earlier. It is unfortunate that we know so little about his contribution to liberal education, a factor which was instrumental in India's freedom.

Sardar Dyal Singh had come to the conclusion well before 1880 that India's salvation lay in the education of the masses. He insisted on spreading English education, and established a college of the most modern kind. He made available the latest books to the Indian people. This the Sardar did through the establishment of a public library well endowed with books.

The establishment of The Tribune was another noteworthy contribution by him. The aim of the newspaper was to spread the doctrine of Indian nationalism and to bring about unity in a society that was afflicted by differences on questions of religion, caste, language and region. His nationalism was also reflected in his strong support for the foundation of the Indian National Congress.

A man who could analyse so clearly, a century and a half ago, the reasons for the downfall of the people of our country from the very top of the civilised world to its very bottom and then establish the institutions which would generate the forces to restore it to its old position, can only be regarded as a genius with great foresight and courage. He died on September 9, 1898.Top

***

A visionary with a difference

by V. N. DattaTHE 19th century Punjab was at the bottom optimistic and melioristic and believed that something radical could be done about all sorts of arrangements in society that would promote material well-being and intellectual advancement. Each age leaves its mark on its generation. Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia had a different cast of mind from those of his forefathers. This was so because he belonged to an era of vital social and economic changes as contrasted with the period which was marked by military adventurism and political chicanery.

Dyal Singh Majithia had a lively and questioning mind. He had influential social connections which gave him entree into every political and intellectual sphere partaking fully in the life around him. The whole story of Sardar Majithia cannot be reconstructed without recourse to conjecture and imagination as the documentary evidence helpful for some parts of his life is almost wholly lacking for others.

He belonged to the family of the distinguished ruling chiefs of Punjab, who had held high positions in the times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his successors. His grandfather, Sardar Desa Singh, was Ranjit Singh's trusted military general who was later appointed the Governor of the hill states of Mandi and Saket. He also acted as the civil administrator of Harmander Sahib in Amritsar, a responsibility he discharged with fervour. Because of his meritorious services Ranjit Singh conferred on him the title of "Kisrul-Iktdar". Sir Lepel Griffin estimated Desa Singh's income from various jagirs and other sources at 1,24,250 per annum. Desa Singh died in 1832, leaving behind three sons: Lehna Singh, Gujar Singh and Ranjodh Singh.

Dyal's father, Lehna Singh, was an extraordinary man and, in many ways, an innovator. He was highly respected for his integrity of character, mild manners and amiable disposition. He inherited a major portion of his father's estates. He acted also as the Governor of the hill states and was the chief administrator of Harmandar Sahib. Deeply interested in science, he set up his own laboratory for conducting experiments. Through his contacts with the British he acquainted himself with scientific knowledge in England and procured some literature on the subject for his own studies. An engineer, he improved the Punjab foundries and invented the clock which showed the day, the month and the changes in the moon. Though deeply interested in astronomy he was not converted to the Copernican system and still continued to believe in the earth's immobility.

Ranjit Singh was greatly impressed by Lehna Singh's diplomatic finesse and, therefore, sent him on several diplomatic missions to negotiate with the British on important political matters. In this connection he met Lord William Bentinck, Lord Auckland, Lord Ellenborough and Alexander Burnes. He was conferred the title of Hasham-ud-Daula (Lord of the State). During Chand Rani's brief regime of violence and disorder it was proposed to appoint him as Prime Minister, but he was considered too mild a person for such a challenging task which needed ruthlessness and twisting of politics. When he witnessed how Punjab was breaking up due to the sinister designs and high-handedness of a few self-aggrandising and self-destructive individuals overpowered by overweening ambition during Mesar Julla's regime, he left Punjab to settle in Benaras where Dyal Singh was born in 1849.

Henry Lawrence, the British Resident, who had much sympathy for the Punjab Chiefs, persuaded Lehna Singh to return to Punjab and appointed him a member of the Council of Regency in August, 1847. Henry Lawrence had high opinion of him and thought him the "most sensible Sardar in the Punjab", but also noted his timidity in recourse to action when it was needed. Lehna Singh avoided controversies and loathed pettyfogging and intrigues. He foresaw the rolling clouds of disaster for Punjab and, therefore, left for Benaras again on January 14, 1848, and never to return. Lehna Singh died in 1854 leaving his five-year-old son, Dyal Singh, under the tutelage of Sardar Teja Singh, formerly the Commander-in-Chief and a member of the Council of the Regency. Dyal Singh inherited a large patrimony from his father. The most significant feature of the history of Punjab in the 19th century was its remarkable process of modernisation, and in this transformation certain aspects of urbanisation gained prominence, the various channels producing the changes were education, the Press, the means of transport and communications, the bureaucratic set-up and land settlement. It is not often realised that in the transformation of Punjab the Punjabi elite played a vital role to which Kenneth Jones in his studies has drawn our attention.

Dyal Singh kept himself substantially in touch with some of the influential members of the Bengali elite in Lahore. He had great admiration for the Brahmo Samaj which had initiated social and educational reform in Bengal. It was Surendranath Banerjea who had suggested to Dyal Singh the idea of setting up an independent paper for creating an enlightened public opinion in Punjab. In his memoirs, Surendranath Banerjea wrote about Dyal Singh: "He was one of the truest and noblest men I have come across. It was perhaps difficult to know him and to get the better of his heart for there was a certain reserve about him which hid from public view pure gold that formed the stuff of his nature."

Seetalchandra Mookerjee served as the first Editor of The Tribune who was followed by Seetalakanta Chatterjee and B.C. Pal. During the 1919 disturbances Kalinath Ray was the Editor who was tried and arrested. Gandhiji had to intervene on his behalf and send a petition to the Viceroy about his release.

The Tribune became a success within a short time so much so that when Dennis Fitzpatrick was the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab a civilian wrote to The Pioneer of Lucknow that Punjab was ruled by the Lieutenant-Governor and The Tribune. It remained Dyal Singh's cardinal principle not to interfere in the working and management of the paper, and he left complete freedom to the Editor to use his discretion in running the paper. He emphasised in his Will that the paper should remain entirely free from any taint of communalism which was vitiating the atmosphere in Punjab.

Aristocratic in bearing, Dyal Singh was a reserved and taciturn person. He was a man of few words. Not a profound thinker, ideologue or scholar of the library, he possessed immense Punjabi commonsense of seeing the reality of things. He disdained controversies. This does not mean that he kept himself aloof when important issues of national interest were involved.

Dr G.W. Leitner, Principal of the newly created Government College, founded the Anjuman-i-Punjab with the objective of reviving oriental learning, particularly the study of Sanskrit and Arabic. His objective was like that of orientalist H.H. Wilson to promote Western learning through the medium of classical languages and vernaculars. The old Macaulay-orientalist controversy was being revived in Punjab. Dyal Singh differed from Leitner's views. He regarded the English language as the "key to all improvements". He firmly believed that Western knowledge could only be imparted in India through the medium of English. That he thought was the only way to regenerate Indian society as had been previously shown by the experiment in Bengal.

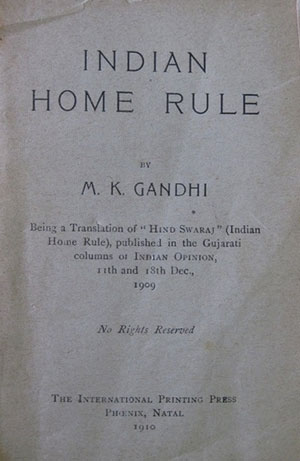

The very first issue of The Tribune on February 2, 1881, stood for the promotion of modern knowledge through the English language. About 25 articles supported by strongly-worded editorials in The Tribune knocked down Leitner's argument and created a strong public opinion in favour of Dyal Singh's stand on higher education. Ultimately, the government had to yield! Though separate arrangements for imparting oriental learning were made, instruction in higher education began to be given through the medium of English.

Dyal Singh Majithia, a public spirited liberal imbued with lofty ideals, left a rich legacy of a creative force calculated to produce far-reaching consequences for generations to come. His institutions continue to function in Punjab and elsewhere and act as a stimulus to the lives of so many people. Unfortunately, political developments took a different turn from what he had envisioned. He was out-and-out a liberal person, but his liberalism got swamped by the rising tide of communalism which led to the Partition of India. The value system he had projected with his insightful intellect has much relevance for us. He had the vision of a secular, prosperous Punjab, free from conflicts, and bustling with ideas and verve.

***

An educationist par excellence

by Justice Dalip K. KapurSHAKESPEARE, perhaps better than anybody else, gave expression to the fundamental emotions and desires of humanity. Heroes or villains, lovers or warriors, kings or politicians, valiant heroines, ghosts, murderers, and, above all, patriots; he had them all. Splendidly displayed in evocative iambic pentameter. Fate and Destiny were two ideas he often referred to. Yet scholars doubt that he wrote the poems and the plays he did. But who wrote them? That is a question that has puzzled scholars over the years.

Our own Kalidas was said to be an idiot, but he was suddenly blessed with overwhelming poetic brilliance. His poetry was filled with brilliant imagery. How did he get his powers?

One of the ideas that obsessed Shakespeare was Immortality. How does one live after death? It is a universal idea. Does one go to heaven or hell or fade into oblivion? Is one reborn? Shakespeare's ideal was to live through his work. He expressed himself best on this point in his sonnets. This is what he said in Sonnet LV Lines 1-4:

Not marble nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone besmear'd with sluttish time.

Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia lives even today. So we remember him on his 100th death anniversary. We also remember him on occasions. Some persons live in history books, some by writings, some by their preaching of ideas, some are poets or philosophers, writers, religious leaders and so on. Sardar Dyal Singh lives through the institutions he created. Few mortals have managed to do this. How did he do what he did? He was an unlikely person to create enduring institutions. He did, however, achieve immortality.

His first creation was The Tribune. The only other worthwhile Indian-owned newspaper of those times was The Hindu of Madras. It is quite remarkable that Dyal Singh could achieve the impossible, create a newspaper in a foreign language, only a few years after Punjab was annexed. And what a newspaper!

How did it come about that a person like Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia conceived the idea of a newspaper? One must remember that he was a land owner; he was educated up to the school-level. There were no university degrees given in Punjab at that time. He was financially very rich; he bought jewels; he bought property. He constructed several buildings in Lahore, Amritsar and Karachi. He was honoured by the British as the head of the Shergil clan. He was rich but unsatisfied. He was part of the Indian revival. He had many Bengali, Christian or Brahmo Samaji friends. He was convinced that he had to do something more than live a life of luxury, which a Punjab chief might ordinarily have lived. He had ideas, which were broadened by visits to Europe. He brought those ideas to life.

The newspaper started as a weekly, but expanded into a nationalist daily of tremendous power and prestige. It was bold and fearless, which refused to be cowed down by the British. It was given to investigative journalism at a time when that expression had not even been invented. Its leading articles shook the Empire and brilliantly evoked the idea of the poor Indian oppressed by the greedy Englishman. Every misdoing, every misdemeanour, every act of misgovernment was fully exposed to the public. It is not possible to reproduce the substance of the editorial writings, which were outstanding, in this short article. It is sufficient to say that one can be proud of what was said, particularly, at the time it was said, when Indian self-esteem was at its lowest ebb.

The newspaper grew from strength to strength during the life-time of the founder. Now it was time to do something different. Sardar Dyal Singh launched Punjab National Bank, the first Punjabi bank. He was the principal shareholder and Chairman. Lala Harkishan Lal, a kindred spirit, was the secretary. This bank soon gained strength and popularity. It became major bank in Lahore. It had a huge building on Mall Road, next to the General Post Office.

Sardar Dyal Singh had vast property in Lahore, Amritsar and Majitha. He made a will creating three trusts. These were the Tribune Trust, the Dyal Singh College Trust and the Dyal Singh Public Library Trust. He appointed three eminent lawyer-friends to be the trustees of The Tribune, but included some educationists, and among them was Dewan (later Raja) Narendra Nath in the College Trust. In the Library Trust, he included some well-known persons. The college and library took shape quite a long time after the Sardar's death, as the will was challenged by the widow and another lady, Mrs Catherine Gill, who claimed to be Dyal Singh's wife. The case was fought up to the Privy Council. The judgements upheld the Trust and give a good picture of Sardar Dyal Singh's philanthropy and reputation.

The college was very successful. Though not the leading college in Lahore, it came to be known as one of the better colleges in Punjab. The library was housed in a lovely building and was the second public library in Lahore, the first being Punjab Public Library. They both had collections of about 30,000 to 40,000 books. Undoubtedly Punjab Public Library was bigger, but Dyal Singh Library was catching up, though it was established about 40 or 50 years later.

Then came Partition. All the three Trusts were wrecked, as they were located in Lahore, and had nowhere to go in East Punjab. Now was the time for action by the trustees. The Tribune was financially well off, so it opened a new office in Ambala, bought a new press and started anew. Naturally, the fact that most of its readers were left in Pakistan meant that its operations were smaller, but at least it became a national paper. Unfortunately, its pre-eminent position as the leading national paper of India was lost, as it was located in a small town.

The College Trust was well-endowed with property in Majitha and Amritsar, so it was able to start functioning again at Karnal and in New Delhi. Dewan Anand Kumar, Vice-Chancellor of Punjab University, who was the main Trustee, was responsible for opening the college at both places. The Karnal college had a small beginning but went on improving. The New Delhi college was very well housed. It had a beautiful building, and was doing well, but the government put some restrictions which forced the trustees to give up the college. It was the hardest decision to make. Huge amounts of money, the college building and all its assets were given to Delhi University. This was one of the blackest deeds of the national government. It was forced because the trust could not run the college under the University Grants Commission. It had no way to meet the deficit, all the income was taken by the commission and the trust was required to meet the deficit from "other sources", which was impossible as there were no "other sources". When the college was set up in New Delhi, the Central Government had done its best to rehabilitate the refugee college through the Rehabilitation Ministry, but later the government evolved an unworkable scheme, which led to the trust giving up its assets to save the college from closure. The college is still called Dyal Singh College, New Delhi, but no longer under the trust.

The Karnal college, on the other hand, has gone from strength to strength. The 10+2 policy, and the creation of the university at Kurukshetra, had led to the college having only a two-year B.A. course. That is not enough. The trustees with immense vigour and enterprise have set up Dyal Singh School, which is one of the leading schools of the area providing education up to the secondary level. A huge new building is under construction. The efforts regarding the college and the school principally of Dewan Anand Kumar and now Dewan Gajendra Kumar, have resulted in the creation of an institution of which the Sardar would be proud. There is now a move for some post-graduate courses. Some have already been started.

The library has had the worst deal in Partition. All its assets were buildings in Lahore. Even after Partition, Dyal Singh Library, Lahore, is functioning, but now it is run by the Pakistan Government. All that the trustees, who all came to India, had brought was a small liquid deposit. With severe constraints, the trustees put up a building in the Rouse Avenue area, New Delhi (now Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg). There were no funds, no books, only efforts and more efforts. The building had to be let out to various other institutions, the meagre funds available had to be husbanded and the income carefully used to increase the assets. A reading room was opened at Connaught Place. It was open and free to the public. A reading room with a small collection was also opened in the main building. Gradually, an improvement took place. A writ in the High Court, which is still pending, led the Government of Delhi paying increased rent. Later the building was vacated and greater rent received. So after a 50-year struggle, the library has become functional. Now it has big plans. A multi-purpose library is proposed, with a media section, using all the latest techniques. Internet connections, film shows, lectures, demonstrations, CD-Roms, audio-video-visual media will be there. Great hopes and aspirations are there.

The Sardar founded these trusts with great care. His trustees were well-chosen, and they have tried to keep his inspiring philosophy alive. Even Partition has not killed the trusts. They are alive. Sardar Dyal Singh lives on. He still inspires.

***

The Tribune, ChandigarhHow The Tribune was launched

The Tribune, ChandigarhHow The Tribune was launchedSEVERAL people have claimed the credit for giving Dyal Singh the idea of starting a newspaper in English from Lahore. The foremost among them was Surendranath Banerjea, who wrote that he persuaded Dyal Singh to start the paper. Rai Bahadur Mul Raj wrote that he and Jogendra Chandra Bose requested Dyal Singh to start a newspaper to carry on the crusade for education in Punjab on Western lines through the medium of English. This, he says, was in 1877 or 1878.

Bipin Chandra Pal, a member of the famous Lal-Bal-Pal trio, who was on the staff of Dyal Singh's paper for a few months, says that the Sardar started the paper at the suggestion of his Bengali friends in Lahore. One issue of The Tribune said that the idea was the Sardar's own. This could well be so.

During his sojourn abroad for two years, Dyal Singh had seen the importance of the role played by an independent Press. Within months of his return from Europe, he came into contact with Surendranath Banerjea and discussed his ideas in regard to starting an English language newspaper from Lahore. Soon he was involved in the controversy over the Vernacular Press Act.

The Indian Association's meeting in the Town Hall in Calcutta had nominated him to be a member of the steering committee set up to oversee the implementation of the Press Act. This was in 1878. Surendranath Banerjea was certainly the person who encouraged him. So also were his close Brahmo Bengali friends in Lahore, particularly P.C. Chatterjee, a senior member of the Lahore Bar, who later rose to be a Judge of the Chief Court; and Jogendra Chandra Bose, another member of the Lahore Bar.

The launching of a newspaper in Punjab was not an easy task at that time. Printing machinery had to be procured and the staff had to be recruited. Dyal Singh solicited the help of Surendranath Banerjea. The latter promised all help. Banerjea arranged the printing Press. He also recommended the name of Sitalakanta Chatterjee for appointment on the editorial staff. Being young, he was appointed Sub-Editor, because the newspaper must have some maturer person for the Editor's job. Thanks to Dyal Singh's Brahmo Bengali friends' help, he was able to get the services of Seetalchandra Mookerjee of Bhowanipore in Calcutta, who lived in Upper India and was editing his own paper, The Indian People, from Allahabad. He promised to edit the proposed Lahore paper from Allahabad itself.

Trained journalists being scarce in those days, Dyal Singh agreed to the arrangement. Seetalchandra Mookerjee sent the editorials and special articles from Allahabad, Sitalakanta Chatterjee looking after the work at Lahore. Dyal Singh himself made the other appointments. He recruited P.K.Chatterjee who had done some scissoring and pasting job at The Pioneer's sister publication in Lahore, The Civil and Military Gazette. For the job of the printer he fixed up with R. Williams, who had worked for The Indian Chronicle.

The first issue of The Tribune, which came out on February 2, 1881, took up the cause of modern education in Punjab through the medium of English. Week after week it carried as many as 25 articles in addition to editorials demolishing the arguments of the "orientalists", Dr Leitner and his supporters. The other members of the Panjab University College Senate asked how Dyal Singh could continue to be a member of the Senate when his paper was opposing the policies of Panjab University College, which supported Dr Leitner. Dyal Singh resigned his membership of the Senate, and The Tribune continued its crusade. As the President of the Lahore branch of the Indian Association, he involved the headquarters of the organisation in Calcutta to take up the issue with the Secretary of State for India in London. The crusade was crowned with success when the British government agreed in 1882 to the establishment of Panjab University on the lines of the universities in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras. The battle was won.

Dyal Singh's Bengali Brahmo friends played an important role in making The Tribune more than a mere provincial paper. Modelled on The Bengalee, it was a paper which claimed to represent the whole of Upper India. It took up not only all-India issues but also international issues, such as they were in the last century. The number of the copies of The Tribune sold outside Punjab was more than the number of the copies sold inside the province.

Significantly, the first issue championed the cause of The Statesman Defence Fund, being raised to fight for The Statesman's pro-India Editor, Robert Knight, who had been sued by a Hyderabad nobleman at the instance of diehard British bureaucrats in India, who had been upset at the exposure by The Statesman (through its London edition) of the working of British bureaucrats here. Dyal Singh himself was a member of The Statesman Defence Committee. The Tribune took up all the public causes, and its voice was taken note of. It is said that one Lieut-Governor of Punjab advised a delegation meeting him to ventilate their grievances through the columns of The Tribune. British civilians of Punjab felt so unhappy as to tell their compatriots that the province was being ruled by the Lieut-Governor and The Tribune, and the civil servants were nowhere.

The exposure of public wrongs once led to a famous defamation case, filed in 1890, by a Superintendent of Police against Dyal Singh and the Editor of The Tribune. One of the factors mentioned by the Superintendent of Police was that Dyal Singh was a nationalist and had allowed the compound of his baronial mansion in Amritsar to be used for a lecture by a Congress agitator named Allah Ram.

M.G.

***

Spreading the light of learning

by Brig Yash Beotra (retd)"PROPAGATION of sound liberal education and dissemination of knowledge to inculcate pure morality", was one of the cherished obsessions with Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia, a many splendoured personality. And to achieve this lifetime wish of his, he bequeathed assets worth over Rs 30 lakh way back in 1895, through a will, the last will and testament of his, to establish three premium institutions in Lahore (now in Pakistan):

(1) The Tribune, to spread knowledge through the print medium.

(2) Dyal Singh College, to disseminate knowledge through formal education.

(3) Dyal Singh Public Library, to spread knowledge through books.

The library was closer to his heart, as Sardar Majithia was himself a voracious reader, with a personal collection of more than 1000 volumes on various subjects. He dedicated his palatial building in the elite area of Lahore for establishing a premier public library.

This selfless action distinguishes him as a rare philanthropist of the country in the 19th century. It is a fact, though unfortunate, that in these days of greed and selfishness very few have the predilection to launch ventures for the benefit of humanity suffering for want of the bare necessities of life. Though numerous saints and sages have delivered sermons to humanity to renounce wealth for the good of mankind, little tangible has been achieved. Deepening greed has prevented people from undertaking munificent projects. In our own lifetime, Vinoba Bhave tried his utmost to inspire people to philanthropy but, alas, the exercise was short-lived. Seen in the light of all this, the movement of philanthropy spearheaded by the late Sardar should be a great source of inspiration and set an example for other Indians to follow. It may be worth mentioning here that bequeathing assets for the purpose of spreading knowledge was uncommon even in western countries then.

Sardar Majithia had the foresight to visualise that the charity of "Vidya Dhan", wealth of knowledge, was the highest deed one could do. He was of the firm view that instead of spending his wealth, which he had earned so assiduously, on building temples and dharamshalas, he should use it for the dissemination of knowledge and the spread of liberal education, the best use one can think of. This was the dire need of Punjab then, as it was plagued by superstition and useless customs.

But what made his mission a great success was his commendable foresight. He was able to find people having a high sense of commitment, dedication and, above all, unquestionable integrity for maintaining the three trusts as conceived by him. The trustees functioned in an exemplary manner, making the trusts premier institutions. The Partition of the country in 1947 forced their temporary closure in Lahore. But this did not dampen the spirits of the dedicated trustees, who managed to get the three institutions revived in India, the tireless efforts put in by the late Dewan Anand Kumar for re-establishing the college and the library trusts need special mention. Today, Dyal Singh Public Library is the only institution of its kind which is functioning as per the wishes of the late Sardar both in Pakistan (Lahore) and India (New Delhi).

Dyal Singh Trust Library, Lahore, was established in 1928, in pursuance of the will of Sardar Majithia. It enjoyed great popularity before Partition. In 1947, it suffered a considerable loss due to riots in Lahore, and a good number of its books and furniture were damaged. It remained closed for 12 years due to the migration of its non-Muslim trustees. It started functioning in 1964 when its control was taken over by the Evacuee Trust Property Board, Government of Pakistan, Lahore. Today, it is managed by the Education Department, Government of Punjab, Pakistan, through a board of trustees, under the chairmanship of the Commissioner, Lahore Division. The library has a collection of over 1,40,000 volumes, both in English and oriental languages. It has a research cell which has so far brought out 26 publications, both in Urdu and English, apart from publishing a quarterly journal, Minhaj.

After Partition, through the efforts of Dewan Anand Kumar, the first Vice-Chancellor of Panjab University, and other trustees, the Dyal Singh Library Trust Society was established afresh in India, on August 2, 1948. The purpose of the society was to establish a library for the use of the general public subject to such rules and regulations as the trustees might frame, provided no charge would be levied for the perusal of books and newspapers and magazines in the library during its hours of business.

The library was set up in the institutional area of Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, New Delhi, not far from the ITO, the busiest crossing overlooking Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, by undertaking the construction of a sprawling building during 1954-55, on a 1.3 acre plot of land, leased out by the government for the purpose. Since it is located at a very central place, well connected by road and rail networks, users find it convenient to visit the library.

Though, initially, the library functioned at a low key due to the paucity of funds, since 1993 the Trust Society under the chairmanship of Mr B.K. Nehru launched itself on a massive programme with much improved financial health, achieved as a result of sound planning and assistance from government agencies as allowed under the rules. This action to enlarge the scope of its activities has enabled it to take a few steps on the path to becoming a premier library in Delhi in particular and the country in general.

The library has over 35,000 volumes, some of these being rare, mainly in English, Hindi, Urdu and Punjabi. It subscribes to 91 magazines/journals, including 12 foreign journals and 23 daily newspapers. With the availability of such a large number of books, newspapers and magazines free of charge, the membership of the library has shown a steady growth over the past few years. Today it has over 4,600 members, including over 1500 lending members, a category which has deposited Rs 300 per head as a refundable security amount and which allows such a person to borrow at a time two books and two old magazines for study at his/her residence. Over 150 members visit the library daily.

The management has undertaken a number of plans to modernise the library. The process of its automation was launched some time back. Today, the English section is fully automated. This has enabled it to become a member of the Delhi Library Network, Delnet, which provides Dyal Singh Public Library the added advantage of resource sharing among the member-libraries in Delhi. In addition, through a well-planned and organised "Perspective Plan of Action", covering the visualised expansion of the library over the next 15-20 years, a state-of-art auditorium, seminar/committee rooms and a cafeteria are proposed to be provided soon. The Internet facility is also there for use by the members as well as the library staff who can now effectively carry out bibliographical search.

***

A pioneer in banking sector too

by Prakash TandonSoon after the new British regime settled down to governance, the Punjabi elite were looking for creating a modern educational, industrial, banking base to activate the Punjabi enterprise with the needed wherewithal to develop. The man who made a unique contribution to this process was a scion of an elite Jagirdar Punjab family, Dyal Singh Majithia, a new born liberal. He realised the importance of creating a wide base of institutions to develop the new Punjab.

Lehna Singh, his father, was quite remarkable in his time for his fondness of mechanics. He paid much attention to his battery of guns in which he brought about great improvements, and made some very efficient pieces of ordnance which were captured by the British in the Battle of Aliwal. He is also said to have invented a clock which showed the hour, the day of the month, and the changes in the month. He was an expert linguist and took keen interest in mathematics and astronomy. At the request of Ranjit Singh he reformed the calendar, for which he won a name among Hindu astronomers.

After Lehna Singh's death in 1854 at Benaras, his family moved back to their substantial jagir at Majitha. Competent tutors were appointed for Dyal Singh in a government Court of Wards before he went to a Mission School, and was placed under an English governess. In his early years he displayed considerable charm, intelligence and eagerness for knowledge. He was tall, graceful in figure, with sharp well-cut features, and fond of both sports and learning. Dyal Singh was installed with proper ceremonies as the head of the Shergil clan, which through the next century produced ministers, administrators and an early remarkable modern painter, Amrita Shergil, born of a Hungarian mother.

Dyal Singh made, what was at that time, a startling decision, to go abroad to complete his education and to learn about the West, especially Britain, their mode of living and their institutions which fascinated him. The conservatives in the community regarded it an unholy act that the son of the great Lehna Singh should cross the seas and eat, live and drink with the Kiranis (Christians) in their distant land. Like Maharaja Dalip Singh, the first Sikh to go abroad, he would surely embrace Christianity, they feared. He spent two years in England, visiting Europe, where he experienced the new wave of nationalism and forces of thought of the period following the Franco-Prussian War. His lineage, name and noble figure made him popular in the Victorian society among persons of both ranks and scholarship.

Upon his return from England, he decided to move from Majitha to Lahore, where he could take active interest in the new movements that were sweeping the city. He combined the life of a Sikh nobleman with patronage of sports, mushairas and music, sumptuous hospitality, and new ideas. He came under the influence of the Brahmo Samaj, a movement founded in Bengal in 1828 by Raja Rammohun Roy.

In 1877, when Swami Dayanand visited Punjab, he met the Sardar and they discussed the question of the infallibility of the Vedas, but Dyal Singh was not convinced. He had already studied the Bhagavad-Gita with a Ferozepur pundit and the Bible, evincing great interest in the crucifixion of Christ.

In the early 1880s, the Indian Association was organised at Lahore and as its first President, he began to guide and influence the new youth movement. He also took active interest in the new Indian National Congress and was made Chairman of the Reception Committee on the occasion of the first Congress session at Lahore in 1893. He believed and stated that political rights must be deserved by his countrymen by liberalising their social customs, shedding their shackles, and spreading liberal education.

His greatest contribution perhaps was in the area of institution building. The rugged individualism of the Punjabis made them averse to forming and working together in voluntary associations. Dyal Singh, on the other hand, was an admirer of British institutions and their parliamentary system, though he did not like the bureaucracy and never cultivated its executive officers. He saw the need to build institutions in Punjab and in less than two decades founded a number of them; the Dyal Singh High School, College and Library. He helped all institutions with which he was associated with wisdom and guidance.

In his inaugural address as the Chairman of the Reception Committee of the Indian National Congress in Lahore in 1893, he made a moving appeal to Indians and the British alike, perhaps the first of its kind at a time when their relationship was already beginning to show strain. He said: "What the Congress contends is not that the country should be transferred from English to Indian hands; no, not change of hands, for it would be entirely suicidal, but that the people should be governed on the broad principles which have been held by the eminent British statesmen and administrators themselves to be the most conducive to the interests of both rulers and the subjects".

Punjab National Bank emerged in the late nineteenth century, inheriting the traditions of ancient trade and banking and influenced by the impact of modern British banks, depicting the resurgence of the new Punjab. One of the ideals of the new elite was to start their own modern bank, professionally run with Indian capital and management, wide public participation and no personal control or ownership. Lajpat Rai, the great political leader, wrote: "Rai Mul Raj of Arya Samaj specially had long cherished the idea that Indians should have a National Bank of their own." He was keenly concerned with the fact that though Indian capital was being used to run English banks and companies, the profits went entirely to the British, while Indians had to contend themselves with a small interest on their capital.

Mul Raj described the idea of Punjab National Bank, as it took shape in his mind (Beginning of Punjabi Nationalism: autobiography of R.B. Mul Raj thus: "In the year 1891, when I was the Judge of the small Causes Court at Amritsar, I was living in a house in Mohalla Khatikan. I had set apart one room as my study for reading books on Dharma-Shastras. There I conceived the idea of organizing a National Bank in the Punjab. It struck me that it was necessary to have a national bank for the development of industries in the country, and that we should have the custody and final say in the investment of our money.

To keep this idea foremost in my mind, I wrote 'National Bank' on a piece of paper and fixed it on the wall. I used to talk on the subject daily with my friends and acquaintances. It was not easy to convince my friends that it was practicable to have a bank managed and controlled by Punjabis. Gradually I succeeded in making some of them take interest in the subject. One of these gentlemen was Lala Bulaki Ram Shastri, Bar-at-Law, who was practising at Amritsar those days. He designed the cheque which is still being used by Punjab National Bank Ltd. The five wavy lines represent the five rivers of the Punjab, the three peaks of mountains represent Tirathkoti, while Devi Shir represent Lakshmi - the Goddess of wealth and prosperity, and the monogram PNB for Punjab National Bank Ltd. Many other friends came round to my views. I met Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia, who agreed to become the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Bank."

On May 23, 1894, the founders, Mr E C Jessawala, Babu Kali Prasono Roy, Bakshi Jaishi Ram, Lala Harkishan Lal, Lala Bulaki Ram and Lala Lal Chand, met at the Lahore residence of Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia and resolved to go ahead with the scheme. The new Bank had then the most remarkable feature of being held by public shareholders and run by professional board of directors, consisting of a banker, three lawyers, a barrister and a businessman, chaired by Dyal Singh. They met on alternate Sundays. It had a staff of eight : an accountant, a treasurer, a clerk, a daftari, two chaprasis and two chowkidars on a total monthly wage bill of Rs.170.

It was open to the public from 10.00 a.m. to 3.30 p.m. The Bank's success was immediate and in two years its paid up capital rose from Rs.41,500 to Rs.1,09,495; deposits from Rs.1,65,337 to Rs.7,27,447; net profit from Rs.1,555 to Rs.15,536 and dividend from 4% to 5%.

Thus was born the first Indian public bank, which today is over a century old and the largest Indian bank in its operations within India.

Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia left us a hundred years ago, during which his bank's contribution to Punjab has been remarkable to its farmers: small, medium and large industrialists; the middle class savers and investors. The question today is how we take the past into the future, the next century and soon the next millennium.

***

His role in the birth of Panjab UniversitySARDAR Dyal Singh Majithia was largely responsible for the setting up of Panjab University, Lahore, in 1882. Punjab was annexed in 1849. The Education Department was set up in 1854. Students travelled to Calcutta for examinations. Panjab University College, as it was called, was affiliated to Calcutta University, but it gave only diplomas, not degrees.

Punjab was among the last to be annexed to the British empire. It was to be the gateway to the Central Asian region which the British wished to advance to. For the administration of Punjab, the British had brought along with them civilians, lawyers and teachers from Bengal. And Bengal had seen the advance of education, enlightenment and national awakening. British officials did not want Punjab to be affected. And one way to ensure this was to impart education not through the medium of English but through Indian classical languages. In effect, it meant the imposition of a pattern different from that of the Calcutta, Bombay and Madras Universities. Dr W.G. Lietner, a Central European Jew, who had mastered Arabic and Islamic theology, was sent out to India to take charge of educational advancement in Punjab. An important person already there was Col W.R.M. Holroyd, Director of Instruction, who had made Lahore take the place of Lucknow and Delhi as the principal centre of Urdu learning. That is why he had invited Hali and Muhammed Hussain Azad to emigrate to Lahore.

Leitner and Holroyd and their British friends were strongly opposed to the adoption of English as the medium of instruction. Their move was opposed by the younger generation which wanted education to be given on the lines of that in London, Madras, Calcutta and Bombay. The debate was on when Dyal Singh returned from a two-year sojourn to the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe. His closest friends in Punjab were not the Sikh nobility but Bengalee Brahmos. Dyal Singh, who played host to all the Brahmo leaders visiting Punjab, enlisted their help and support in starting The Tribune, which was to espouse the cause of education on Western lines. The Tribune launched a campaign for the setting up of Panjab University modelled on the universities at Calcutta, Bombay, Madras or London, the medium of instruction being English. Editorially, week after week it rebutted the arguments of the orientalists. Some 20 articles appeared.

Now Dyal Singh was a nominated member of the Senate of Panjab University College as it was then called. The Senate consisted of the Sikh aristocracy, most of them without much education. The other members of the Senate, under the influence of the orientalists, drew the attention to the fact that one of the members was opposing their policy. Dyal Singh resigned his membership of the Senate, and continued with the campaign. His stand was supported by the Indian Association, whose Lahore branch he headed. While the Indian Association's President and Secretary and others sent petitions to the Secretary of State for India in London, Dyal Singh and his friends continued the pressure on the Lieut-Governor and the Viceroy.

It was a hard battle. Ultimately, however, Dyal Singh's side won, and the British decided in 1882 that the medium of instruction and the pattern of teaching at Panjab University will be the same as that in the three presidencies in Eastern, Western and Southern India. As Jogendra Bose, an important member of the Lahore Bar Association, wrote later, "Dr Leitner backed by immense influence tried his best to orientalise education in the Punjab, but Sardar Dyal Singh proved instrumental in saving the situation. A battle was won."