by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/10/19

Maurice Strong is also a member of the Bahai World Faith. With Haifa, in Israel, as the site of its international headquarters, the Bahai movement now exercises a strong presence in the United Nations and its One-World Religion agenda. Its involvement in the UN dates back to its founding in 1945. In 1948, the Bahai community was recognized as an international non-governmental organization. In May 1970, they were granted consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), and later with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The Bahai organization has a working relationship with the World Health Organization (WHO), is associated with the UN Environment Programme, as well as many other religious, environmental and social programs.

-- Chapter Twenty-Two: One-World-Religion, Terrorism and the Illuminati: A Three Thousand Year History, by David Livingston

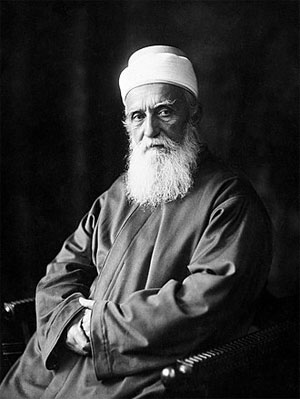

`Abdu'l-Bahá

Personal

Born `Abbás

23 May 1844

Tehran, Persia

Died 28 November 1921 (aged 77)

Haifa, Palestine

Resting place Shrine of `Abdu'l-Bahá

32°48′52.59″N 34°59′14.17″ECoordinates: 32°48′52.59″N 34°59′14.17″E

Religion Bahá'í Faith

Nationality Persian

Spouse Munírih Khánum (m. 1873)

Children 4 (incl. Ḍíyá'íyyih Khánum)

Parents Bahá'u'lláh (father)

Ásíyih Khánum (mother)

Relatives Shoghi Effendi (grandson)

`Abdu’l-Bahá' (/əbˈdʊl bəˈhɑː/; Persian: عبد البهاء, 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born `Abbás (Persian: عباس), was the eldest son of Bahá'u'lláh and served as head of the Bahá'í Faith from 1892 until 1921.[1] `Abdu’l-Bahá was later canonized as the last of three "central figures" of the religion, along with Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb, and his writings and authenticated talks are regarded as a source of Bahá'í sacred literature.[2]

He was born in Tehran to an aristocratic family. At the age of eight his father was imprisoned during a government crackdown on the Bábí Faith and the family's possessions were looted, leaving them in virtual poverty. His father was exiled from their native Iran, and the family went to live in Baghdad, where they stayed for nine years. They were later called by the Ottoman state to Istanbul before going into another period of confinement in Edirne and finally the prison-city of `Akká (Acre). `Abdu’l-Bahá remained a political prisoner there until the Young Turk Revolution freed him in 1908 at the age of 64. He then made several journeys to the West to spread the Bahá'í message beyond its middle-eastern roots, but the onset of World War I left him largely confined to Haifa from 1914–1918. The war replaced the openly hostile Ottoman authorities with the British Mandate, who knighted him for his help in averting famine following the war.

In 1892 `Abdu'l-Bahá was appointed in his father's will to be his successor and head of the Bahá'í Faith. He faced opposition from virtually all his family members, but held the loyalty of the great majority of Bahá'ís around the world. His Tablets of the Divine Plan helped galvanize Bahá'ís in North America into spreading the Bahá'í teachings to new territories, and his Will and Testament laid the foundation for the current Bahá'í administrative order. Many of his writings, prayers and letters are extant, and his discourses with the Western Bahá'ís emphasize the growth of the faith by the late 1890s.

`Abdu'l-Bahá's given name was `Abbás. Depending on context, he would have gone by either Mírzá `Abbás (Persian) or `Abbás Effendi (Turkish), both of which are equivalent to the English Sir `Abbás. He preferred the title of `Abdu'l-Bahá ("servant of Bahá", a reference to his father). He is commonly referred to in Bahá'í texts as "The Master".

Early life

`Abdu'l-Bahá was born in Tehran, Iran on 23 May 1844 (5th of Jamadiyu'l-Avval, 1260 AH),[3] the eldest son of Bahá'u'lláh and Navváb. He was born on the very same night on which the Báb declared his mission.[4] Born with the given name of `Abbás,[2] he was named after his grandfather Mírzá `Abbás Núrí, a prominent and powerful nobleman.[5] As a child, `Abdu'l-Bahá was shaped by his father's position as a prominent Bábí. He recalled how he met the Bábí Táhirih and how she would take "me on to her knee, caress me, and talk to me. I admired her most deeply".[6] `Abdu’l-Bahá had a happy and carefree childhood. The family’s Tehran home and country houses were comfortable and beautifully decorated. `Abdu'l-Bahá enjoyed playing in the gardens with his younger sister with whom he was very close.[7] Along with his younger siblings – a sister, Bahíyyih, and a brother, Mihdí – the three lived in an environment of privilege, happiness and comfort.[5] With his father declining a position as minister of the royal court; during his young boyhood `Abdu’l-Bahá witnessed his parents' various charitable endeavours,[8] which included converting part of the home to a hospital ward for women and children.[7]

`Abdu'l-Bahá received a haphazard education during his childhood. It was customary not to send children of nobility to schools. Most noblemen were educated at home briefly in scripture, rhetoric, calligraphy and basic mathematics. Many were educated to prepare themselves for life in the royal court. Despite a brief spell at a traditional preparatory school at the age of seven for one year,[9] `Abdu'l-Bahá received no formal education. As he grew he was educated by his mother, and uncle.[10] Most of his education however, came from his father.[11] Years later in 1890 Edward Granville Browne described how `Abdu'l-Bahá was "one more eloquent of speech, more ready of argument, more apt of illustration, more intimately acquainted with the sacred books of the Jews, the Christians, and the Muhammadans...scarcely be found even amongst the eloquent."[12]

When `Abdu'l-Bahá was seven, he contracted tuberculosis and was expected to die.[13] Though the malady faded away,[14] he would be plagued with bouts of illness for the rest of his life.[15]

One event that affected `Abdu'l-Bahá greatly during his childhood was the imprisonment of his father when `Abdu'l-Bahá was eight years old; the imprisonment led to his family being reduced to poverty and being attacked in the streets by other children.[4] `Abdu'l-Bahá accompanied his mother to visit Bahá'u'lláh who was then imprisoned in the infamous subterranean dungeon the Síyáh-Chál.[5] He described how "I saw a dark, steep place. We entered a small, narrow doorway, and went down two steps, but beyond those one could see nothing. In the middle of the stairway, all of a sudden we heard His [Bahá’u’lláh's]…voice: 'Do not bring him in here', and so they took me back".[14]

Baghdad

Bahá'u'lláh was eventually released from prison but ordered into exile, and `Abdu'l-Bahá then eight joined his father on the journey to Baghdad in the winter (January to April)[16] of 1853.[14] During the journey `Abdu'l-Bahá suffered from frost-bite. After a year of difficulties Bahá'u'lláh absented himself rather than continue to face the conflict with Mirza Yahya and secretly secluded himself in the mountains of Sulaymaniyah in April 1854 a month before `Abdu'l-Bahá's tenth birthday.[16] Mutual sorrow resulted in him, his mother and sister becoming constant companions.[17] `Abdu'l-Bahá was particularly close to both, and his mother took active participation in his education and upbringing.[18] During the two-year absence of his father `Abdu'l-Bahá took up the duty of managing the affairs of the family,[19] before his age of maturity (14 in middle-eastern society)[20] and was known to be occupied with reading and, at a time of hand-copied scriptures being the primary means of publishing, was also engaged in copying the writings of the Báb.[21] `Abdu’l-Bahá also took an interest in the art of horse riding and, as he grew, became a renowned rider.[22]

In 1856, news of an ascetic carrying on discourses with local Súfí leaders that seemed to possibly be Bahá'u'lláh reached the family and friends. Immediately, family members and friends went to search for the elusive dervish – and in March[16] brought Bahá'u'lláh back to Baghdad.[23] On seeing his father, `Abdu'l-Bahá fell to his knees and wept loudly "Why did you leave us?", and this followed with his mother and sister doing the same.[22][24] `Abdu'l-Bahá soon became his father's secretary and shield.[4] During the sojourn in the city `Abdu’l-Bahá grew from a boy into a young man. He was noted as a "remarkably fine looking youth",[22] and remembered for his charity and amiableness.[4] Having passed the age of maturity `Abdu'l-Bahá was regularly seen in the mosques of Baghdad discussing religious topics and the scripture as a young man. Whilst in Baghdad, `Abdu'l-Bahá composed a commentary at the request of his father on the Muslim tradition of "I was a Hidden Treasure" for a Súfí leader named `Alí Shawkat Páshá.[4][25] `Abdu'l-Bahá was fifteen or sixteen at the time and `Alí Shawkat Páshá regarded the more than 11000 word essay as a remarkable feat for somebody of his age.[4] In 1863 in what became known as the Garden of Ridván Bahá'u'lláh announced to a few that he was the manifestation of God and He whom God shall make manifest whose coming had been foretold by the Báb. On day eight of the twelve days, it is believed `Abdu'l-Baha was the first person Baha'u'llah revealed his claim to.[26][27]

Constantinople/Adrianople

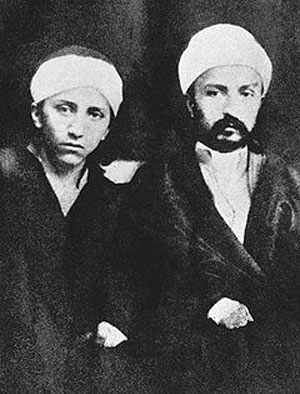

`Abdu'l-Bahá (right) with his brother Mírzá Mihdí

In 1863 Bahá'u'lláh was summoned to Constantinople (Istanbul), and thus his whole family including `Abdu'l-Bahá, then nineteen, accompanied him on his 110-day journey.[28] The journey to Constantinople was another wearisome journey,[22] and `Abdu'l-Bahá helped feed the exiles.[29] It was here that his position became more prominent amongst the Bahá’ís.[2] This was further solidified by Bahá’u’lláh’s tablet of the Branch in which he constantly exalts his son's virtues and station.[30] The family were soon exiled to Adrianople and `Abdu'l-Bahá went with the family.[2] `Abdu’l-Bahá again suffered from frostbite.[22]

In Adrianople `Abdu’l-Bahá was regarded as the sole comforter of his family – in particular to his mother.[22] At this point `Abdu'l-Bahá was known by the Bahá'ís as "the Master", and by non-Bahá'ís as `Abbás Effendi ("Effendi" signifies "Sir"). It was in Adrianople that Bahá’u’lláh referred to his son as "the Mystery of God".[22] The title of "Mystery of God" symbolises, according to Bahá'ís, that `Abdu'l-Bahá is not a manifestation of God but how a "person of `Abdu'l-Bahá the incompatible characteristics of a human nature and superhuman knowledge and perfection have been blended and are completely harmonized".[31][32] `Abdu'l-Bahá was at this point noted for having black hair which flowed to his shoulders, large blue eyes, rose-through-alabaster coloured skin and a fine nose.[33] Bahá'u'lláh gave his son many other titles such as Ghusn-i-A'zam (meaning "Mightiest Branch" or "Mightier Branch"),[a] the "Branch of Holiness", "the Center of the Covenant" and the apple of his eye.[2] `Abdu'l-Bahá ("the Master") was devastated when hearing the news that he and his family were to be exiled separately from Bahá'u'lláh. It was, according to Bahá'ís, through his intercession that the idea was reverted and the family were allowed to be exiled together.[22]

`Akká

Prison in `Akká where Bahá’u’lláh and his family were housed

At the age of 24, `Abdu'l-Bahá was clearly chief-steward to his father and an outstanding member of the Bahá’í community.[28] Bahá’u’lláh and his family were – in 1868 – exiled to the penal colony of Acre, Palestine where it was expected that the family would perish.[34] Arrival in `Akká was distressing for the family and exiles.[2] They were greeted in a hostile manner by the surrounding population and his sister and father fell dangerously ill.[4] When told that the women were to sit on the shoulders of the men to reach the shore, `Abdu'l-Bahá took a chair and carried the women to the bay of `Akká.[22] `Abdu'l-Bahá was able to procure some anesthetic and nursed the sick.[22] The Bahá’ís were imprisoned under horrendous conditions in a cluster of cells covered in excrement and dirt.[4] `Abdu'l-Bahá himself fell dangerously ill with dysentery,[4] however a sympathetic soldier permitted a physician to help cure him.[22] The population shunned them, the soldiers treated them the same, and the behaviour of Siyyid Muhammad-i-Isfahani (an Azali) did not help matters.[5][35] Morale was further destroyed with the accidental death of `Abdu'l-Bahá’s youngest brother Mírzá Mihdí at the age of 22.[22] His death devastated the family – particularly his mother and father – and the grieving `Abdu'l-Bahá kept a night-long vigil beside his brother’s body.[5][22]

Later in `Akká

Over time, he gradually took over responsibility for the relationships between the small Bahá'i exile community and the outside world. It was through his interaction with the people of `Akká (Acre) that, according to the Bahá'ís, they recognized the innocence of the Bahá'ís, and thus the conditions of imprisonment were eased.[36] Four months after the death of Mihdí the family moved from the prison to the House of `Abbúd.[37] The people of `Akká started to respect the Bahá'ís and in particular, `Abdu'l-Bahá. `Abdu'l-Bahá was able to arrange for houses to be rented for the family, the family later moved to the Mansion of Bahjí around 1879 when an epidemic caused the inhabitants to flee.

`Abdu'l-Bahá soon became very popular in the penal colony and Myron Henry Phelps a wealthy New York lawyer described how "a crowd of human beings...Syrians, Arabs, Ethiopians, and many others",[38] all waited to talk and receive `Abdu'l-Bahá.[39] He undertook a history of the Bábí religion through publication of A Traveller's Narrative (Makála-i-Shakhsí Sayyáh) in 1886,[40] later translated and published in translation in 1891 through Cambridge University by the agency of Edward Granville Browne who described `Abdu'l-Bahá as:

Seldom have I seen one whose appearance impressed me more. A tall strongly built man holding himself straight as an arrow, with white turban and raiment, long black locks reaching almost to the shoulder, broad powerful forehead indicating a strong intellect combined with an unswerving will, eyes keen as a hawk's, and strongly marked but pleasing features – such was my first impression of 'Abbás Efendí, "the master".[41]

Marriage and family life

`Abdu'l-Bahá at age 24

When `Abdu'l-Bahá was a young man, speculation was rife amongst the Bahá’ís to whom he would marry.[4][42] Several young girls were seen as marriage prospects but `Abdu’l-Bahá seemed disinclined to marriage.[4] On 8 March 1873, at the urging of his father,[5][43] the twenty-eight-year-old `Abdu’l-Bahá married Fátimih Nahrí of Isfahán (1847–1938) a twenty-five-year-old from an upper-class family of the city.[44] Her father was Mírzá Muḥammad `Alí Nahrí of Isfahan an eminent Bahá’í with prominent connections.[ b][4][42] Fátimih was brought from Persia to `Akká after both Bahá’u’lláh and his wife Navváb expressed an interest in her to marry `Abdu’l-Bahá.[4][44][45] After a wearisome journey from Isfahán to Akka she finally arrived accompanied by her brother in 1872.[4][45] The young couple were betrothed for about five months before the marriage itself commenced. In the meantime, Fátimih lived in the home of `Abdu'l-Bahá’s uncle Mírzá Músá. According to her later memoirs, Fátimih fell in love with `Abdu'l-Bahá on seeing him. `Abdu'l-Bahá himself had showed little inkling to marriage until meeting Fátimih;[45] who was entitled Munírih by Bahá’u’lláh.[5] Munírih is a title meaning "Luminous".[46]

The marriage resulted in nine children. The first born was a son Mihdí Effendi who died aged about 3. He was followed by Ḍiyá'iyyih Khánum, Fu’ádíyyih Khánum (d. few years old), Rúhangíz Khánum (d. 1893), Túbá Khánum, Husayn Effendi (d.1887 aged 5), Túbá Khánum, Rúhá Khánum and Munnavar Khánum. The death of his children caused `Abdu’l-Bahá immense grief – in particular the death of his son Husayn Effendi came at a difficult time following the death of his mother and uncle.[47] The surviving children (all daughters) were; Ḍiyá'iyyih Khánum (mother of Shoghi Effendi) (d. 1951) Túbá Khánum (1880–1959) Rúḥá Khánum and Munavvar Khánum (d. 1971).[4] Bahá'u'lláh wished that the Bahá'ís follow the example of `Abdu'l-Bahá and gradually move away from polygamy.[45][46][48] The marriage of `Abdu’l-Bahá to one woman and his choice to remain monogamous,[45] from advice of his father and his own wish,[45][46] legitimised the practice of monogamy[46] to a people who hitherto had regarded polygamy as a righteous way of life.[45][46]

Early years of his ministry

After Bahá'u'lláh died on 29 May 1892, the Will and Testament of Bahá'u'lláh named `Abdu'l-Bahá as Centre of the Covenant, successor and interpreter of Bahá'u'lláh's writings.[c][49][1]

Bahá'u'lláh designates his successor with the following verses:

The Will of the divine Testator is this: It is incumbent upon the Aghsán, the Afnán and My Kindred to turn, one and all, their faces towards the Most Mighty Branch. Consider that which We have revealed in Our Most Holy Book: ‘When the ocean of My presence hath ebbed and the Book of My Revelation is ended, turn your faces toward Him Whom God hath purposed, Who hath branched from this Ancient Root.’ The object of this sacred verse is none other except the Most Mighty Branch [‘Abdu’l-Bahá]. Thus have We graciously revealed unto you Our potent Will, and I am verily the Gracious, the All-Powerful. Verily God hath ordained the station of the Greater Branch [Muḥammad ‘Alí] to be beneath that of the Most Great Branch [‘Abdu’l-Bahá]. He is in truth the Ordainer, the All-Wise. We have chosen ‘the Greater’ after ‘the Most Great’, as decreed by Him Who is the All-Knowing, the All-Informed.

— Bahá'u'lláh (1994) [1873-92]. "Kitáb-i-`Ahd". Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh Revealed After the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-174-4.

This translation of the Kitáb-i-'Ahd is based on a solecism, however, as the terms Akbar and A'zam do not mean, respectively, 'Greater' and 'Most Great'. Not only do the two words derive from entirely separate triconsonantal roots (Akbar from k-b-r and A'zam from ʿ-z-m), but the Arabic language possesses the elative, a stage of gradation, with no clear distinction between the comparative and superlative.[50] In the Will and Testament `Abdu'l-Bahá's half-brother, Muhammad `Alí, was mentioned by name as being subordinate to `Abdu'l-Bahá. Muhammad `Alí became jealous of his half-brother and set out to establish authority for himself as an alternative leader with the support of his brothers Badi'u'llah and Diya'u'llah.[3] He began correspondence with Bahá'ís in Iran, initially in secret, casting doubts in others' minds about `Abdu'l-Bahá.[51] While most Bahá'ís followed `Abdu'l-Bahá, a handful followed Muhammad `Alí including such leaders as Mirza Javad and Ibrahim George Kheiralla, an early Bahá'í missionary to America.[52]

Muhammad `Alí and Mirza Javad began to openly accuse `Abdu'l-Bahá of taking on too much authority, suggesting that he believed himself to be a Manifestation of God, equal in status to Bahá'u'lláh.[53] It was at this time that `Abdu'l-Bahá, in order to provide proof of the falsity of the accusations leveled against him, in tablets to the West, stated that he was to be known as "`Abdu'l-Bahá" an Arabic phrase meaning the Servant of Bahá to make it clear that he was not a Manifestation of God, and that his station was only servitude.[54][55] `Abdu'l-Bahá left a Will and Testament that set up the framework of administration. The two highest institutions were the Universal House of Justice, and the Guardianship, for which he appointed Shoghi Effendi as the Guardian.[1] With the exception of `Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi, Muhammad `Alí was supported by all of the remaining male relatives of Bahá'u'lláh, including Shoghi Effendi's father, Mírzá Hádí Shírází.[56] However Muhammad `Alí's and his families statements had very little effect on the Bahá'ís in general - in the `Akká area, the followers of Muhammad `Alí represented six families at most, they had no common religious activities,[57] and were almost wholly assimilated into Muslim society.[58]

First Western pilgrims

Early Western Bahá'í pilgrims. Standing left to right: Charles Mason Remey, Sigurd Russell, Edward Getsinger and Laura Clifford Barney; Seated left to right: Ethel Jenner Rosenberg, Madam Jackson, Shoghi Effendi, Helen Ellis Cole, Lua Getsinger, Emogene Hoagg

By the end of 1898, Western pilgrims started coming to Akka on pilgrimage to visit `Abdu'l-Bahá; this group of pilgrims, including Phoebe Hearst, was the first time that Bahá'ís raised up in the West had met `Abdu'l-Bahá.[59] The first group arrived in 1898 and throughout late 1898 to early 1899 Western Bahá’ís sporadically visited `Abdu'l-Bahá. The group was relatively young containing mainly women from high American society in their 20s.[60] The group of Westerners aroused suspicion for the authorities, and consequently `Abdu'l-Bahá’s confinement was tightened.[61] During the next decade `Abdu'l-Bahá would be in constant communication with Bahá'ís around the world, helping them to teach the religion; the group included May Ellis Bolles in Paris, Englishman Thomas Breakwell, American Herbert Hopper, French Hippolyte Dreyfus [fr], Susan Moody, Lua Getsinger, and American Laura Clifford Barney.[62] It was Laura Clifford Barney who, by asking questions of `Abdu'l-Bahá over many years and many visits to Haifa, compiled what later became the book Some Answered Questions.[63]

Ministry, 1901–1912

During the final years of the 19th century, while `Abdu'l-Bahá was still officially a prisoner and confined to `Akka, he organized the transfer of the remains of the Báb from Iran to Palestine. He then organized the purchase of land on Mount Carmel that Bahá'u'lláh had instructed should be used to lay the remains of the Báb, and organized for the construction of the Shrine of the Báb. This process took another 10 years.[64] With the increase of pilgrims visiting `Abdu'l-Bahá, Muhammad `Alí worked with the Ottoman authorities to re-introduce stricter terms on `Abdu'l-Bahá's imprisonment in August 1901.[1][65] By 1902, however, due to the Governor of `Akka being supportive of `Abdu'l-Bahá, the situation was greatly eased; while pilgrims were able to once again visit `Abdu'l-Bahá, he was confined to the city.[65] In February 1903, two followers of Muhammad `Alí, including Badi'u'llah and Siyyid `Aliy-i-Afnan, broke with Muhammad `Ali and wrote books and letters giving details of Muhammad `Ali's plots and noting that what was circulating about `Abdu'l-Bahá was fabrication.[66][67]

From 1902 to 1904, in addition to the building of the Shrine of the Báb that `Abdu'l-Bahá was directing, he started to put into execution two different projects; the restoration of the House of the Báb in Shiraz, Iran and the construction of the first Bahá'í House of Worship in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.[68] `Abdu'l-Bahá asked Aqa Mirza Aqa to coordinate the work so that the house of the Báb would be restored to the state that it was at the time of the Báb's declaration to Mulla Husayn in 1844;[68] he also entrusted the work on the House of Worship to Vakil-u'd-Dawlih.[69]

During this period, `Abdu'l-Bahá communicated with a number Young Turks, opposed to the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, including Namık Kemal, Ziya Pasha and Midhat Pasha, in an attempt to disseminate Bahá'í thought into their political ideology.[70] He emphasized Bahá'ís "seek freedom and love liberty, hope for equality, are well-wishers of humanity and ready to sacrifice their lives to unite humanity" but on a more broad approach than the Young Turks. Abdullah Cevdet, one of the founders of the Committee of Union and Progress who considered the Bahá'í Faith an intermediary step between Islam and the ultimate abandonment of religious belief, would go on trial for defense of Bahá'ís in a periodical he founded.[71][72]

‛Abdu'l-Bahá also had contact with military leaders as well, including such individuals as Bursalı Mehmet Tahir Bey and Hasan Bedreddin. The latter, who was involved in the overthrow of Sultan Abdülaziz, is commonly known as Bedri Paşa or Bedri Pasha and is referred to in Persian Bahá'í sources as Bedri Bey (Badri Beg). He was a Bahá'í who translated ‛Abdu’l-Baha's works into French.[73]

`Abdu'l-Bahá also met Muhammad Abduh, one of the key figures of Islamic Modernism and the Salafi movement, in Beirut, at a time when the two men were both opposed to the Ottoman ulama and shared similar goals of religious reform.[74][75] Rashid Rida asserts that during his visits to Beirut, `Abdu'l-Bahá would attend Abduh's study sessions.[76] Regarding the meetings of `Abdu'l-Bahá and Muhammad 'Abduh, Shoghi Effendi asserts that "His several interviews with the well-known Shaykh Muhammad ‘Abdu served to enhance immensely the growing prestige of the community and spread abroad the fame of its most distinguished member."[77]

Due to `Abdu'l-Bahá's political activities and alleged accusation against him by Muhammad `Ali, a Commission of Inquiry interviewed `Abdu'l-Bahá in 1905, with the result that he was almost exiled to Fezzan.[78][79][80] In response, `Abdu'l-Bahá wrote the sultan a letter protesting that his followers refrain from involvement in partisan politics and that his tariqa had guided many Americans to Islam.[81] The next few years in `Akka were relatively free of pressures and pilgrims were able to come and visit `Abdu'l-Bahá. By 1909 the mausoleum of the Shrine of the Báb was completed.[69]

Journeys to the West

`Abdu'l-Bahá, during his trip to the United States

The 1908 Young Turks revolution freed all political prisoners in the Ottoman Empire, and `Abdu'l-Bahá was freed from imprisonment. His first action after his freedom was to visit the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh in Bahji.[82] While `Abdu'l-Bahá continued to live in `Akka immediately following the revolution, he soon moved to live in Haifa near the Shrine of the Báb.[82] In 1910, with the freedom to leave the country, he embarked on a three-year journey to Egypt, Europe, and North America, spreading the Bahá'í message.[1]

From August to December 1911, `Abdu'l-Bahá visited cities in Europe, including London, Bristol, and Paris. The purpose of these trips was to support the Bahá'í communities in the west and to further spread his father's teachings.[83]

In the following year, he undertook a much more extensive journey to the United States and Canada to once again spread his father's teachings. He arrived in New York City on 11 April 1912, after declining an offer of passage on the RMS Titanic, telling the Bahá'í believers, instead, to "Donate this to charity."[84] He instead travelled on a slower craft, the RMS Cedric, and cited preference of a longer sea journey as the reason.[85] After hearing of the Titanic's sinking on 16 April he was quoted as saying "I was asked to sail upon the Titanic, but my heart did not prompt me to do so."[84] While he spent most of his time in New York, he visited Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., Boston and Philadelphia. In August of the same year he started a more extensive journey to places including New Hampshire, the Green Acre school in Maine, and Montreal (his only visit to Canada). He then travelled west to Minneapolis, San Francisco, Stanford, and Los Angeles before starting to return east at the end of October. On 5 December 1912 he set sail back to Europe.[86]

During his visit to North America he visited many missions, churches, and groups, as well as having scores of meetings in Bahá'ís' homes, and offering innumerable personal meetings with hundreds of people.[87] During his talks he proclaimed Bahá'í principles such as the unity of God, unity of the religions, oneness of humanity, equality of women and men, world peace and economic justice.[87] He also insisted that all his meetings be open to all races.[87]

His visit and talks were the subject of hundreds of newspaper articles.[87] In Boston newspaper reporters asked `Abdu'l-Bahá why he had come to America, and he stated that he had come to participate in conferences on peace and that just giving warning messages is not enough.[88] `Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to Montreal provided notable newspaper coverage; on the night of his arrival the editor of the Montreal Daily Star met with him and that newspaper along with The Montreal Gazette, Montreal Standard, Le Devoir and La Presse among others reported on `Abdu'l-Bahá's activities.[89][90] The headlines in those papers included "Persian Teacher to Preach Peace", "Racialism Wrong, Says Eastern Sage, Strife and War Caused by Religious and National Prejudices", and "Apostle of Peace Meets Socialists, Abdul Baha's Novel Scheme for Distribution of Surplus Wealth."[90] The Montreal Standard, which was distributed across Canada, took so much interest that it republished the articles a week later; the Gazette published six articles and Montreal's largest French language newspaper published two articles about him.[89] His 1912 visit to Montreal also inspired humourist Stephen Leacock to parody him in his bestselling 1914 book Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich.[91] In Chicago one newspaper headline included "His Holiness Visits Us, Not Pius X but A. Baha,"[90] and `Abdu'l-Bahá's visit to California was reported in the Palo Altan.[92]

Back in Europe, he visited London, Paris (where he stayed for two months), Stuttgart, Budapest, and Vienna. Finally, on 12 June 1913, he returned to Egypt, where he stayed for six months before returning to Haifa.[86]

On 23 February 1914, at the eve of World War I, `Abdu'l-Bahá hosted Baron Edmond James de Rothschild, a member of the Rothschild banking family who was a leading advocate and financier of the Zionist movement, during one of his early trips to Palestine.[93]

Final years (1914–1921)

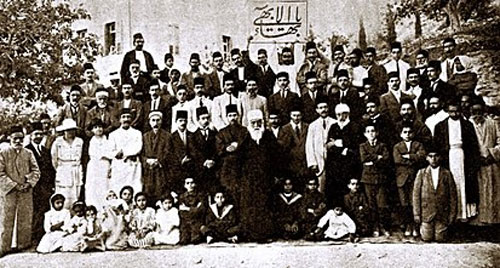

`Abdu'l-Bahá on Mount Carmel with pilgrims in 1919

During World War I (1914–1918) `Abdu'l-Bahá stayed in Palestine and was unable to travel. He carried on a limited correspondence, which included the Tablets of the Divine Plan, a collection of 14 letters addressed to the Bahá'ís of North America, later described as one of three "charters" of the Bahá'í Faith. The letters assign a leadership role for the North American Bahá'ís in spreading the religion around the planet.

Haifa was under real threat of Allied bombardment, enough that `Abdu'l-Bahá and other Bahá'ís temporarily retreated to the hills east of `Akka.[94]

`Abdu'l-Bahá was also under threats from Cemal Paşa, the Ottoman military chief who at one point expressed his desire to crucify him and destroy Bahá'í properties in Palestine.[95] The surprisingly swift Megiddo offensive of the British General Allenby swept away the Turkish forces in Palestine before harm was done to the Bahá'ís, and the war was over less than two months later.

Post-war period

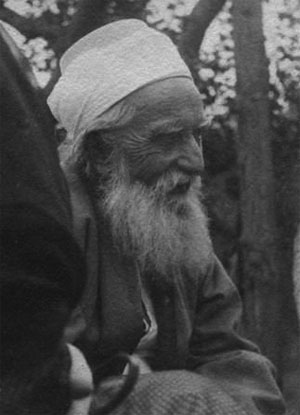

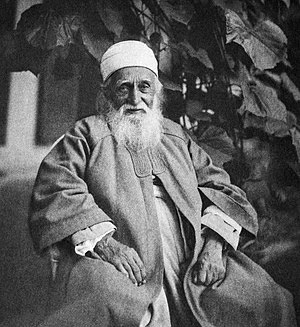

The elderly `Abdu'l-Bahá

The conclusion of World War I led to the openly hostile Ottoman authorities being replaced by the more friendly British Mandate, allowing for a renewal of correspondence, pilgrims, and development of the Bahá'í World Centre properties.[96] It was during this revival of activity that the Bahá'í Faith saw an expansion and consolidation in places like Egypt, the Caucasus, Iran, Turkmenistan, North America and South Asia under the leadership of `Abdu'l-Bahá.

The end of the war brought about several political developments that `Abdu'l-Bahá commented on. The League of Nations formed in January 1920, representing the first instance of collective security through a worldwide organization. `Abdu'l-Bahá had written in 1875 for the need to establish a "Union of the nations of the world", and he praised the attempt through the League of Nations as an important step towards the goal. He also said that it was "incapable of establishing Universal Peace" because it did not represent all nations and had only trivial power over its member states.[97][98] Around the same time, the British Mandate supported the ongoing immigration of Jews to Palestine. `Abdu'l-Bahá mentioned the immigration as a fulfillment of prophecy, and encouraged the Zionists to develop the land and "elevate the country for all its inhabitants... They must not work to separate the Jews from the other Palestinians."[99]

`Abdu'l-Bahá at his knighting ceremony, April 1920

The war also left the region in famine. In 1901, `Abdu'l-Bahá had purchased about 1704 acres of scrubland near the Jordan river and by 1907 many Bahá'ís from Iran had begun sharecropping on the land. `Abdu'l-Bahá received between 20-33% of their harvest (or cash equivalent), which was shipped to Haifa. With the war still raging in 1917, `Abdu'l-Bahá received a large amount of wheat from the crops, and also bought other available wheat and shipped it all back to Haifa. The wheat arrived just after the British seized control, and the wheat was widely distributed to allay the famine.[100][101] For this service in averting a famine in Northern Palestine he received a knighthood at a ceremony held in his honor at the home of the British Governor on 27 April 1920.[102][103] He was later visited by General Allenby, King Faisal (later king of Iraq), Herbert Samuel (High Commissioner for Palestine), and Ronald Storrs (Military Governor of Jerusalem).[104]

Death and funeral

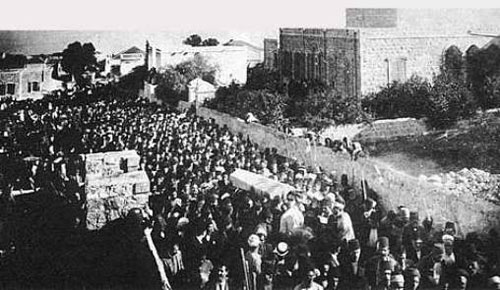

Funeral of `Abdu'l-Bahá in Haifa, British Mandate-Palestine

`Abdu'l-Bahá died on Monday, 28 November 1921, sometime after 1:15 a.m. (27th of Rabi' al-awwal, 1340 AH).[105]

Winston Churchill telegraphed the High Commissioner for Palestine, "convey to the Bahá'í Community, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, their sympathy and condolescence." Similar messages came from Viscount Allenby, the Council of Ministers of Iraq, and others.[106]

On his funeral, which was held the next day, Esslemont notes:

... a funeral the like of which Haifa, nay Palestine itself, had surely never seen... so deep was the feeling that brought so many thousands of mourners together, representative of so many religions, races and tongues.[107]

Among the talks delivered at the funeral, Shoghi Effendi records Stewart Symes giving the following tribute:

Most of us here have, I think, a clear picture of Sir ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá ‘Abbás, of His dignified figure walking thoughtfully in our streets, of His courteous and gracious manner, of His kindness, of His love for little children and flowers, of His generosity and care for the poor and suffering. So gentle was He, and so simple, that in His presence one almost forgot that He was also a great teacher, and that His writings and His conversations have been a solace and an inspiration to hundreds and thousands of people in the East and in the West.[108]

He was buried in the front room of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel. His interment there is meant to be temporary, until his own mausoleum can be built.

Legacy

`Abdu'l-Bahá left a Will and Testament that was originally written between 1901-1908 and addressed to Shoghi Effendi, who at that time was only 4-11 years old. The will appoints Shoghi Effendi as the first in a line of Guardians of the religion, a hereditary executive role that may provide authoritative interpretations of scripture. `Abdu'l-Bahá directed all Bahá'ís to turn to him and obey him, and assured him of divine protection and guidance. The will also provided a formal reiteration of his teachings, such as the instructions to teach, manifest spiritual qualities, associate with all people, and shun Covenant-breakers. Many obligations of the Universal House of Justice and the Hands of the Cause were also elaborated.[109][1] Shoghi Effendi later described the document as one of three "charters" of the Bahá'í Faith.

The authenticity and provisions of the will were almost universally accepted by Bahá'ís around the world, with the exception of Ruth White and a few other Americans who tried to protest Shoghi Effendi's leadership.

During his lifetime there was some ambiguity among Bahá'ís as to his station relative to Bahá'u'lláh, and later to Shoghi Effendi. Some American newspapers reported him to be a Bahá'í prophet or the return of Christ. Shoghi Effendi later formalized his legacy as the last of three "Central Figures" of the Bahá'í Faith and the "Perfect exemplar" of the teachings, also claiming that holding him on an equal status to Bahá'u'lláh or Jesus was heretical. Shoghi Effendi also wrote that during the anticipated Bahá'í dispensation of 1000 years there will be no equal to `Abdu'l-Bahá.[110]

Works

The total estimated number of tablets that `Abdu'l-Bahá wrote are over 27,000, of which only a fraction have been translated into English.[111] His works fall into two groups including first his direct writings and second his lectures and speeches as noted by others.[1] The first group includes The Secret of Divine Civilization written before 1875, A Traveller's Narrative written around 1886, the Resāla-ye sīāsīya or Sermon on the Art of Governance written in 1893, the Memorials of the Faithful, and a large number of tablets written to various people;[1] including various Western intellectuals such as August Forel which has been translated and published as the Tablet to Auguste-Henri Forel. The Secret of Divine Civilization and the Sermon on the Art of Governance were widely circulated anonymously.

The second group includes Some Answered Questions, which is an English translation of a series of table talks with Laura Barney, and Paris Talks, `Abdu'l-Baha in London and Promulgation of Universal Peace which are respectively addresses given by `Abdu'l-Bahá in Paris, London and the United States.[1]

The following is a list of some of `Abdu'l-Bahá's many books, tablets, and talks:

• Foundations of World Unity

• Memorials of the Faithful

• Paris Talks

• Secret of Divine Civilization

• Some Answered Questions

• Tablets of the Divine Plan

• Tablet to Auguste-Henri Forel

• Tablet to The Hague

• Will and Testament of `Abdu'l-Bahá

• Promulgation of Universal Peace

• Selections from the Writings of 'Abdu'l-Bahá

• Divine Philosophy

• Treatise on Politics / Sermon on the Art of Governance[112]

See also

• Bahá'u'lláh's family

• Mírzá Mihdí

• Ásíyih Khánum

• Bahiyyih Khánum

• Munirih Khánum

• Shoghi Effendi

• House of `Abdu'l-Bahá

Explanatory notes

1. The elative is a stage of gradation in Arabic that can be used both for a superlative or a comparative. Ghusn-i-A'zam could mean "Mightiest Branch" or "Mightier Branch"

2. The Nahrí family had earned their fortune from a successful trading business. They won the favor of the leading ecclesiastics and nobility of Isfahan and had business transactions with royalty.

3. In the Kitáb-i-`Ahd Bahá'u'lláh refers to his eldest son `Abdu'l-Bahá as Ghusn-i-A'zam (meaning "Mightiest Branch" or "Mightier Branch") and his second eldest son Mírzá Muhammad `Alí as Ghusn-i-Akbar (meaning "Greatest Branch" or "Greater Branch").

Notes

1. Iranica 1989.

2. Smith 2000, pp. 14-20.

3. Muhammad Qazvini (1949). "`Abdu'l-Bahá Meeting with Two Prominent Iranians". Retrieved 5 September 2007.

4. Esslemont 1980.

5. Kazemzadeh 2009

6. Blomfield 1975, p. 21

7. Blomfield 1975, p. 40

8. Blomfield 1975, p. 39

9. Taherzadeh 2000, p. 105

10. Blomfield, p.68

11. Hogenson 2010, p. 40

12. Browne 1891, p. xxxvi.

13. Hogenson, p.81

14. Balyuzi 2001, p. 12.

15. Hogenson, p.82

16. Chronology of persecutions of Babis and Baha'iscompiled by Jonah Winters

17. Blomfield 1975, p. 54

18. Blomfield 1975, p. 69

19. The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, volume two, page 391

20. Can women act as agents of a democratization of theocracy in Iran? by Homa Hoodfar, Shadi Sadr, page 9

21. Balyuzi 2001, p. 14.

22. Phelps 1912, pp. 27–55

23. Smith 2008, p. 17

24. Balyuzi 2001, p. 15.

25. 'Abdu'l-Bahá. "'Abdu'l-Baha's Commentary on The Islamic Tradition: "I Was a Hidden Treasure ..."". Baha'i Studies Bulletin 3:4 (Dec. 1985), 4–35. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

26. Declaration of Baha'u'llah

27. The history and significance of the Bahá'í festival of Ridván BBC

28. Balyuzi 2001, p. 17.

29. Kazemzadeh 2009.

30. "Tablet of the Branch". Wilmette: Baha'i Publishing Trust. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

31. "The Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh". US Bahá’í Publishing Trust. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

32. "The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh". Baha'i Studies Bulletin 3:4 (Dec. 1985), 4–35. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

33. Gail & Khan 1987, pp. 225, 281

34. Foltz 2013, pp. 238

35. Balyuzi 2001, p. 22.

36. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 33–43.

37. Balyuzi 2001, p. 33.

38. Phelps 1912, pp. 3

39. Smith 2000, pp. 4

40. A Traveller's Narrative, (Makála-i-Shakhsí Sayyáh)

41. `Abdu'l-Bahá (1891), Browne, E.G. (Tr.), ed., A Traveller's Narrative: Written to illustrate the episode of the Bab, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. (See Browne's "Introduction" and "Notes", esp. "Note W".)

42. Hogenson, p.87

43. Ma'ani 2008, p. 112

44. Smith 2000, p. 255

45. Phelps 1912, pp. 85–94

46. Smith 2008, p. 35

47. Ma'ani 2008, p. 323

48. Ma'ani 2008, p. 360

49. Taherzadeh 2000, p. 256.

50. MacEoin, Denis (June 2001). "Making the Crooked Straight, by Udo Schaefer, Nicola Towfigh, and Ulrich Gollmer: Review". Bahá'í Library Online. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

51. Balyuzi 2001, p. 53.

52. Browne 1918, p. 145

53. Browne 1918, p. 77

54. Balyuzi 2001, p. 60.

55. Abdul-Baha. "Tablets of Abdul-Baha Abbas".

56. Smith, Peter (2000). A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 169–170. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

57. Warburg, Margit. Bahá'í: Studies in Contemporary Religion. Signature Books. p. 64. ISBN 1-56085-169-4. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013.

58. MacEoin, Denis. "Bahai and Babi Schisms". Iranica. In Palestine, the followers of Moḥammad-ʿAlī continued as a small group of families opposed to the Bahai leadership in Haifa; they have now been almost wholly re-assimilated into Muslim society.

59. Balyuzi 2001, p. 69.

60. Hogenson, p.x

61. Hogenson, p.308

62. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 72–96.

63. Balyuzi 2001, p. 82.

64. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 90–93.

65. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 94–95.

66. Balyuzi 2001, p. 102.

67. Afroukhteh 2003, p. 166

68. Balyuzi 2001, p. 107.

69. Balyuzi 2001, p. 109.

70. Alkan, Necati (2011). "The Young Turks and the Bahá'ís in Palestine". In Ben-Bassat, Yuval; Ginio, Eyal. Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 262. ISBN 978-1848856318.

71. Hanioğlu, M. Şükrü (1995). The Young Turks in Opposition. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0195091151.

72. Polat, Ayşe (2015). "A Conflict on Baha'ism and Islam in 1922: Abdullah Cevdet and State Religious Agencies"(PDF). Insan & Toplum. 5 (10). Archived from the original(PDF) on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

73. Alkan, Necati (2011). "The Young Turks and the Bahá'ís in Palestine". In Ben-Bassat, Yuval; Ginio, Eyal. Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 266. ISBN 978-1848856318.

74. Scharbrodt, Oliver (2008). Islam and the Bahá'í Faith: A Comparative Study of Muhammad 'Abduh and 'Abdul-Baha 'Abbas. Routledge. ISBN 9780203928578.

75. Cole, Juan R.I. (1983). "Rashid Rida on the Bahai Faith: A Utilitarian Theory of the Spread of Religions". Arab Studies Quarterly. 5 (2): 278.

76. Cole, Juan R.I. (1981). "Muhammad `Abduh and Rashid Rida: A Dialogue on the Baha'i Faith". World Order. 15 (3): 11.

77. Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. p. 193. ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

78. Alkan, Necati (2011). "The Young Turks and the Bahá'ís in Palestine". In Ben-Bassat, Yuval; Ginio, Eyal. Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 263. ISBN 978-1848856318.

79. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 111–113.

80. Momen 1981, pp. 320–323

81. Alkan, Necati (2011). "The Young Turks and the Bahá'ís in Palestine". In Ben-Bassat, Yuval; Ginio, Eyal. Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule. I.B.Tauris. p. 264. ISBN 978-1848856318.

82. Balyuzi 2001, p. 131.

83. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 159–397.

84. Lacroix-Hopson, Eliane; `Abdu'l-Bahá (1987). `Abdu'l-Bahá in New York- The City of the Covenant. NewVistaDesign. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013.

85. Balyuzi 2001, p. 171.

86. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 159-397.

87. Gallagher & Ashcraft 2006, p. 196

88. Balyuzi 2001, p. 232.

89. Van den Hoonaard 1996, pp. 56–58

90. Balyuzi 2001, p. 256.

91. Wagner, Ralph D. Yahi-Bahi Society of Mrs. Resselyer-Brown, The. Accessed on: 19 May 2008

92. Balyuzi 2001, p. 313.

93. "February 23, 1914". Star of the West. 9 (10). 8 September 1918. p. 107. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

94. Effendi 1944, p. 304.

95. Smith 2000, p. 18.

96. Balyuzi 2001, pp. 400–431.

97. Esslemont 1980, pp. 166-168.

98. Smith 2000, p. 345.

99. "Declares Zionists Must Work with Other Races". Star of the West. 10 (10). 8 September 1919. p. 196.

100. McGlinn 2011.

101. Poostchi 2010.

102. Luke, Harry Charles (23 August 1922). The Handbook of Palestine. London: Macmillan and Company. p. 59.

103. Religious Contentions in Modern Iran, 1881-1941, by Mina Yazdani, PhD, Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 2011, pp. 190-191, 199–202.

104. Effendi 1944, p. 306-307.

105. Effendi 1944, p. 311.

106. Effendi 1944, p. 312.

107. Esslemont 1980, p. 77, quoting 'The Passing of `Abdu'l-Bahá", by Lady Blomfield and Shoghi Effendi, pp 11, 12.

108. Effendi 1944, pp. 313-314.

109. Smith 2000, p. 356-357.

110. Effendi 1938.

111. Universal House of Justice (September 2002). "Numbers and Classifications of Sacred Writings texts". Retrieved 20 March 2007.

112. Translations of Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Texts Vol. 7, no. 1 (March 2003)

References

• Afroukhteh, Youness (2003) [1952], Memories of Nine Years in 'Akká, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-477-8

• Balyuzi, H.M. (2001), `Abdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh (Paperback ed.), Oxford, UK: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-043-8

• Bausani, Alessandro (1989), "'Abd-al-Bahā' : Life and work", Encyclopædia Iranica.

• Blomfield, Lady (1975) [1956], The Chosen Highway, London, UK: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, ISBN 0-87743-015-2

• Effendi, Shoghi (1938). The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-231-7.

• Effendi, Shoghi (1944), God Passes By, Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, ISBN 0-87743-020-9

• Browne, E.G. (1918), Materials for the Study of the Bábí Religion, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

• Esslemont, J.E. (1980), Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.), Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust, ISBN 0-87743-160-4

• Foltz, Richard (2013), Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 1-85168-336-4

• Gail, Marzieh; Khan, Ali-Kuli (31 December 1987). Summon up remembrance. G. Ronald. ISBN 978-0-85398-259-3.

• Gallagher, Eugene V.; Ashcraft, W. Michael (2006), New and Alternative Religions in America, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-98712-4

• Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2009), "'Abdu'l-Bahá 'Abbás (1844–1921)", Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project, Evanston, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States.

• McGlinn, Sen (22 April 2011). "Abdu'l-Baha's British knighthood". Sen McGlinn's Blog.

• Momen, M. (editor) (1981), The Bábí and Bahá'í Religions, 1844–1944 – Some Contemporary Western Accounts, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-102-7

• Momen, Moojan (2003). "The Covenant and Covenant-Breaker". bahai-library.com. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

• Phelps, Myron Henry (1912), Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi, New York: Putnam, ISBN 978-1-890688-15-8

• Poostchi, Iraj (1 April 2010). "Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development". Baha'i Studies Review. 16 (1): 61–105.

• Van den Hoonaard, Willy Carl (1996), The origins of the Bahá'í community of Canada, 1898–1948, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, ISBN 0-88920-272-9

• Smith, Peter (2000), A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, ISBN 1-85168-184-1

• Hogenson, Kathryn J. (2010), Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage & Establishment of the Baha'i Faith in the West, George Ronald, ISBN 978-0-85398-543-3

• Ma'ani, Baharieh Rouhani (2008), Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-533-2

• Smith, Peter (2000). A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. pp. 169–170. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

• Taherzadeh, Adib (2000). The Child of the Covenant. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-439-5.

Further reading

• Smith, Peter (2008), An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6

• Zarqáni, Mírzá Mahmúd-i- (1998) [1913], Mahmúd's Diary: Chronicling `Abdu'l-Bahá's Journey to America, Oxford, UK: George Ronald, ISBN 0-85398-418-2

External links

• Works by `Abdu'l-Bahá at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about `Abdu'l-Bahá at Internet Archive

• Works by `Abdu'l-Bahá at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Selections from the Writings of `Abdu'l-Bahá

• Tablets of `Abdu'l-Bahá Abbas

• Abbas Effendi-`Abdu'l-Bahá