The Emergence of Imperial-State Zen and Soldier Zen [Chapter Eight], [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

Second Edition

© 2006 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE EMERGENCE OF IMPERIAL-STATE ZEN AND SOLDIER ZEN

The involvement of Japan's two major Zen sects, Rinzai and Soto, in their country's war effort was not an isolated phenomenon but part of the overall relationship between institutional Buddhism and the Japanese state. It is important to be aware of this because, as Robert Sharf has noted, from the late nineteenth century onward, proponents of Japanese Zen had promoted it not merely as one school of Buddhism but as "the very heart of Asian spirituality, the essence of Japanese culture, and the key to the unique qualities of the Japanese race."1

A parallel development during this period was the tendency to explain Japan's string of Asian military victories as stemming from the allegedly ancient code of Bushido, the Way of the Warrior. Zen spokesmen identified Bushido as the very essence of Japaneseness. If both Zen and Bushido comprised the essence of Japanese culture, the question naturally arises as to the relationship between these two seemingly disparate phenomena.

The answer to this question is the key to understanding the eventual emergence of "imperial-state Zen" (kokoku Zen). A complete investigation of the relationship between Zen and Bushido is both beyond the scope of this book and unnecessary. The important question for our discussion is not the actual historical relationship so much as how Zen adherents from the Meiji period onward perceived and interpreted it. In other words, what did post-Meiji Zen adherents find in the relationship between Zen and Bushido that justified their own fervent support of Japan's war effort?

We have seen that the Meiji-period connection between Zen and martial prowess became pronounced as early as the Russo-Japanese War, thanks to such personages as Rinzai Zen masters Shaku Soen and Nantembo, as well as the latter's famous student, General Nogi Maresuke. A full explication of the symbiotic relationship alleged to exist between Zen and Bushido comes, however, from a rather surprising source.

Nitobe Inazo That source was a book written in English by Dr. Nitobe Inazo (1862-1933) entitled Bushido: The Soul of Japan and published in 1905. The surprising thing about this book is that it was written not by a Buddhist but a Christian, for Dr. Nitobe identified himself as such in the preface. Nevertheless, he stated that he had chosen to act as a "personal defendant" of the creed "I was taught and told in my youthful days, when feudalism was still in force."2

In chapter 2, "Sources of Bushido." Nitobe clarified the relationship between Bushido and Zen as follows:

I may begin with Buddhism. It furnished a sense of calm trust in Fate, a quiet submission to the inevitable, that stoic composure in sight of danger or calamity, that disdain of life and friendliness with death. A foremost teacher of swordsmanship, when he saw his pupil master the utmost of his art, told him, "Beyond this my instruction must give way to Zen teaching."3

Nitobe offered little detailed explanation of Zen teaching, but he did write that:

[Zen's] method is contemplation, and its purport, so far as I understand it, [is] to be convinced of a principle that underlies all phenomena, and, if it Can, of the Absolute itself, and thus to put oneself in harmony with this Absolute. Thus defined, the teaching was more than the dogma of a sect, and whoever attains to the perception of the Absolute rises above mundane things and awakes "to a new Heaven and a new Earth."4

Although Nitobe's discussion of Zen was limited, he was far more forthcoming in his description of Bushido's role in modern Japan: "Bushido, the maker and product of Old Japan, is still the guiding principle of the transition, and will prove the formative force of the new era."5 When Nitobe sought proof of Bushido's ongoing influence on modern Japan, he found it in none other than the Sino-Japanese war:

The physical endurance, fortitude, and bravery that "the little Jap" possesses, were sufficiently proved in the Chino[Sino]-Japanese war. "Is there any nation more loyal and patriotic?" is a question asked by many; and for the proud answer, "There is not." we must thank the Precepts of Knighthood [i.e. Bushido] ....

What won the battles on the Yalu, in Corea and Manchuria, were the ghosts of our fathers, guiding our hands and beating our hearts. They are not dead, those ghosts, the spirits of our warlike ancestors. To those who have eyes to see, they are clearly visible.6

What, then, of the future? Nitobe devoted the last chapter of his book to that very question. On the one hand, he acknowledged that without feudalism, its mother institution, Bushido had been left an orphan. He then suggested that while Japan's modern military might take it under its wing, "we know that modern warfare can afford little room for its continuous growth."7 Would Bushido, then, eventually disappear?

It should come as no surprise to learn that Nitobe didn't believe Bushido was slated for extinction. On the contrary, in the concluding paragraph of his book, he saw it as still "bless [ing] mankind" with "odours ... floating in the air." His book concludes:

Bushido as an independent code of ethics may vanish, but its power will not perish from the earth; its schools of martial prowess or civic honour may be demolished, but its light and its glory will long survive their ruins. Like its symbolic flower, after it is blown to the four winds, it will still bless mankind with the perfume with which it will enrich life.

Ages after, when its customaries will have been buried and its very name forgotten, its odours will come floating in the air as from a far-off, unseen hill, "the wayside gaze beyond"; -then in the beautiful language of the Quaker poet,

"The traveller owns the grateful sense

Of sweetness near, he knows not whence,

And, pausing, takes with forehead bare

The benediction of the air."8

The proponents of imperial-way Buddhism had been able to put forth the remarkable proposition that the Japanese invasion of China was for that country's benefit. Nitobe's intellectual gymnastics here, tying the code of the Japanese warrior to the poetry of a pacifist Quaker, are no less remarkable.

Nukariya Kaiten Nukariya Kaiten, the Soto Zen priest and scholar who wrote The Religion of the Samurai while lecturing at Harvard University in 1913, only eight years after Nitobe published Bushido, was introduced in chapter 5. In his book he maintained that:

Bushido ... should be observed not only by Japan's soldiers on the battlefield, but by every citizen in the struggle for existence. If a person be a person and not a beast, then he must be a samurai -- brave, generous, upright, faithful, and manly, full of self-respect and self-confidence, and at the same time full of the spirit of self-sacrifice. 9

Kaiten may be said to have anticipated the future use of Bushido in two important respects. The first is that in Japan after the Meiji Restoration, everydtizen was expected to adopt the code of the warrior, in what may be regarded as preparation for the militarization of Japanese society as a whole. Second, for all the admonitions to be "generous, upright, faithful." and so forth, "the spirit of self-sacrifice" would come over time, especially after 1937, to be proclaimed the essential element of Bushido.

Shaku Soen Shaku Soen, too, continued speaking out on what he believed Zen could and should contribute to the nation's advancement. In this context, he joined the discussion of Bushido's modern significance in a book entitled A Fine Person, A Fine Horse (Kaijin Kaiba), published in 1919. The date is significant in that World War I had only just ended. Once again, war had become the pretext for a discussion of Zen's contribution to Japan's military prowess.

In Japan's fight against Germany, Soen lamented what he saw as the Japanese people's increasing "materialism." "extreme worship of money." and general decadence. In his mind the solution was clear: "the unification of all the people in the nation in the spirit of Bushido." For Soen, as for Kaiten, the essence of this code was found "in a sacrificial spirit consisting of deep loyalty [to the emperor and the state] coupled with deep filial piety."10.

Where does Zen fit into the picture? Soen's answer was as follows:

The power that comes from Zen training can be called forth to become military power, good government, and the like. In fact, it can be applied to every endeavor. The reason that Bushido has developed so greatly since the Kamakura period is due to Zen, the essence of Buddhism. It was the participation of the Way of Zen which, I believe it can be said, gave to Bushido its great power.11

The belief that the power resulting from Zen training could be converted into military power was to become an ever more important part of the Zen contribution to Japan's war effort. In fact, as will be seen in the following section, it was the basic assumption underlying the emergence of imperial-state Zen. This said, it is equally important to understand that for Soen, the modern role of Bushido, empowered as it was by Zen, was not limited to military action. He emphasized this point yet again when he stated:

Today, my sixty million compatriots are in the maelstrom of a world war. It can be said that not only military men, but also industrialists, politicians, and the general populace are all equipped with a Bushido-like virile and intrepid spirit. As I look toward to the future economic war, however, I cannot help having some doubts as to whether ... there will be persons who can accomplish wonderfully marvelous deeds.12

For Soen, then, not only was Bushido valuable for all segments of society, starting with the military, but it was also equally valuable in Japan's coming "economic wars."

Fueoka Seisen The discussion of the relationship between Zen and Bushido was not limited to scholarly works on Zen or the writings of a few nationalistic Zen masters. On the contrary, it was to be found in even the simplest of introductory books on Zen. A Zen Primer (Zen no Tebiki), published in 1927 by Fueoka Seisen, is an example of such a work. Seisen focused on historical incidents in which he found a connection between Zen and Bushido. Seisen began his discussion of these incidents with the following observation:

Zen was introduced into Japan at the beginning of the Kamakura period, at a time when Bushido had risen to power. The simple and direct teachings of Zen coincided with the straightforward and resolute spirit of samurai discipline. In particular, the Zen teaching on life and death was strikingly dear and thorough. Because samurai stood on the edge between life and death, this teaching was very appropriate for their training. They very quickly came to revere and have faith in it.13

One of the first incidents Seisen introduced was to become probably the most often cited example of the historical connection between Zen and the warrior spirit. It is an exchange between a Chinese Zen master known in Japan as Sogen (Ch. Ziyuan, 1226-86) and his lay disciple, Hojo Tokimune (1251-84), Japan's military ruler. Tokimune was faced with a series of Mongolian invasions that extended over nearly two decades. Seisen recorded the following exchange between Tokimune and Sogen, which supposedly took place after they had heard the news that the Mongolian invaders were seaborne and on their way to attack Japan:

"The great event has come." said Tokimune.

"How will, you face it?" asked Sogen.

"Katsu!" shouted Tokimune.

"Truly a lion's child roars like a lion. Rush ahead and never turn back!" replied Sogen.14

If this exchange marked the first incident in Japan of the linkage of Zen training to mental military preparedness, it also marked, in Seisen's view, "the enhancement of national glory." Martial incidents of this nature revealed that "the spirits of Japan's many heroes have been trained by Zen," and that "Zen and the sword were one and the same."15

Seisen wanted to make sure his readers understood that the Zen spirit which infused Bushido was, in fact, very relevant to the Japan of their day:

Zen enlightenment is not a question of ability, but of power. It is not something acquired through experience, but is the power that immediately gushes to the surface from one's original nature, from one's original form .... This power can be utilized by persons in all fields, including those in the military, industrialists, government ministers, educators, artists, farmers, and others. It underlies all of these pursuits.16

Everyone in contemporary Japan could utilize the power of Zen, just as everyone could benefit from its "strikingly clear and thorough teaching on life and death."

Following the Manchurian Incident of September 1931 and the establishment of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo the following year, Japan entered a period of ever-increasing military activity on the Asian continent, first and foremost in China. Under these circumstances, the need to further strengthen the bonds between Zen, Bushido, and the state became ever more pronounced. One of the first to respond to this need was Sow Zen master Iida Toin.

Iida Toin Given Toin's previously noted praise for General Nogi, it is hardly surprising to find that he devoted an entire chapter of his 1934 book Random Comments on Zen Practice (Sanzen Manroku) to what he called "warrior Zen" (bujin Zen). The titles of its subsections give a good sense of what this chapter was about."''Zen and Bushido." "What is the Spirit of Japan?" "The Essence of the Japanese People." and "The Flower of Loyalty." Toin insisted that the concepts underlying all of these were "unique to Japan" and "beyorid the ability of foreigners to understand."

Toin summarized his argument intbe final section of this chapter, which was entitled "The Perfection of Warrior Zen." The highlights of this section are as follows:

There is truly no end to the numbers of warriors who from ancient times practiced Zen, and it is important to recognize how much power it gave to Bushido. The fact that of late the Zen sect is popular among military men is truly a matter for rejoicing. No matter how much we might practice zazen, if it had no application to today's situation, it would be better not to do it. Are you, at this moment, prepared to die or not? Can you laugh and find eternal peace? Can you face danger without being disturbed? Do you have the great courage required to sacrifice your personal affections for a just cause?

I call on you to wake from your sleep. I call on you to discard your desire for fame and fortune. Without Zen people could not exist. Without people the nation could not exist. Would you put the nation at risk in order to seek fame and fortune for yourself? If you cannot bear to forgo this, what can you bear to forgo? Zen is the general repository for Buddhism. Is not the goal of our practice to save others before we save ourselves? ... The nobility of spirit expressed in the willingness to sacrifice one's life seven times over to repay the debt of gratitude owed the sovereign is purer than the purest snow. Is not sincerity the true essence of the Japanese spirit?

Death is not the end of everything, A basic principle of the universe is that energy does not dissipate and matter is preserved. Those [leaders) who have great strength will ensure the survival of the many. We must take this matter to heart.

Warrior Zen requires no more than to become a warrior. In both the present and the future, and beyond, it is sufficient to be a warrior. To be lionhearted, plunging forward and never retreating -- this is the perfection of warrior Zen.17

Toin was a disciple and eventual Dharma successor of Harada Daiun Sogaku (1870-1961), whose own similar views on this topic will be introduced shortly. If it is possible to transmit the light of the Dharma lamp from master to disciple, perhaps it is also possible to transmit darkness.

Daihorin Discussion By the beginning of 1937 the likelihood of all-out war between Japan and China was growing. As war approached, discussions and writings detailing the connections among Zen, Bushido, and the imperial military increased. One particularly salient discussion took place on January 16, 1937. Sponsored by the major nonsectarian Buddhist magazine Daihorin, the discussion numbered among its participants the prime minister (army general Hayashi Senjuro), another army general, and a navy vice-admiral. In addition, there were lesser-ranking military officers and representatives from both leading academic institutions and the business community.

The purpose of the discussion was "to clarify the direction the people's minds should be heading in light of the present situation." This could only be done, the participants agreed, by looking at "the relationship between Buddhism and the people's spirit."18 Not surprisingly, the ensuing conversation quickly focused on Zen and the contribution it could make to developing the martial spirit of both those within and without the military. The magazine company's president, Ishihara Shummyo, who was also a Soto Zen priest, had this to say:

Zen is very particular about the need not to stop one's mind. As soon as flintstone is struck, a spark bursts forth. There is not even the most momentary lapse of time between these two events. If ordered to face right, one simply faces right as quickly as a flash of lightning. This is proof that one's mind has not stopped.

Zen master Takuan taught ... that in essence Zen and Bushido were one. He further taught that the essence of the Buddha Dharma was a mind which never stopped. Thus, if one's name were called, for example "Vemon," one should simply answer "Yes," and not stop to consider the reason why one's name was called ....

I believe that if one is called upon to die, one should not be the least bit agitated. On the contrary, one should be in a realm where something called "oneself" does not intrude even slightly. Such a realm is no different from that derived from the practice of Zen.19

If the preceding statement may be considered indicative of the spirit that Zen could contribute to the imperial military, the following statement by army major Okubo Koichi, another military participant in the discussion, demonstrates what it was the military, for its part, sought to find in Zen. He said:

[The soldier) must become one with with his superior. He must actually become his superior. Similarly, he must become the order he receives. That is to say, his self must disappear. In so doing, when he eventually goes onto the battlefield, he will advance when told to advance .... On the other hand, should he believe that he is going to die and act accordingly, he will be unable to fight well. What is necessary, then, is that he be able to act freely and without [mental) hindrance.20

Furukawa Taiga If the preceding comments provide a basic conceptual link among selfless Zen, Bushido, and the imperial military, it was left to Furukawa Taigo to present a detailed exposition of the doctrinal relationship among these entities. Furukawa, it will be recalled, was the popular commentator on Buddhism who had written the book Rapidly Advancing Japan and the New Mahayana Buddhism in 1937. According to Furukawa, Bushido had eight major characteristics: (1) great value placed on fervent loyalty; (2) a high esteem for military prowess; (3) an abundance of the spirit of self-sacrifice; (4) realism; (5) an emphasis on practice based on self-reliance; (6) an esteem for order and proper decorum; (7) respect for truthfulness and strong ambition; and (8) a life of simplicity.21

What, then, was the relationship between the above and Zen doctrine? Furukawa noted six points, which I paraphrase below, though there is considerable repetition and overlap among them.

(1) The doctrine of emptiness is the foundation of all Buddhism. It is, furthermore, the fundamental principle of Zen, providing Zen with its practical orientation. For this reason Zen was able to become the driving force behind the self-sacrificing spirit of Bushido, grounded, as the latter is, on the emptiness of self.

(2) The realistic, this-worldly nature of Zen is based on the teaching that our ordinary world of life and death is identical with Nirvana. Zen takes the position that the ordinary world, just as it is, is the ideal world, and it does not seek salvation in the hereafter. This simple, frank, and optimistic spirit of Zen has enabled it to exert a profound influence on the down-to-earth and patriotic spirit of Japan's warriors.

(3) Within the Mahayana branch of Buddhism, the Zen sect alone has faithfully transmitted the thoroughgoing atheism and self-reliance of early Buddhism. Zen abjures reliance on the assistance of Buddhas or gods. Its goal is to see deeply into one's nature and become a Buddha through the single-minded practice of zazen. Zen thus resonated deeply with the independent, self-reliant, and virile spirit of Japan's warriors.

(4) Zeiltakes a very practical stance based on its teaching of the transmission of enlightenment from master to disciple. This transmission takes place independent of the sutras and cannot be expressed in words. Having discarded complicated doctrines, Zen maintains that the Buddha Dharma is synonymous with one's dignified appearance and that proper decorum is the essence of the faith. This is identical to the silent practicality of Bushido, which rejects theoretical argument and instead urges the accomplishment of one's duty.

(5) In leading a plain and frugal life, Zen practitioners maintain a tradition dating back to Buddha Shakyamuni and his first disciples. This life style appealed to the straightforward and unsophisticated warrior temperament, further promoting the development of these qualities among the warrior class.

(6) Unlike Zen in India and China, Japanese Zen was able to transcend the subjective, individualistic, and passive attitude toward salvation that it inherited and become an active, dynamic force influencing the entire nation. It thereby became the catalyst for warriors to enter into the realm of selflessness. This, in turn, resulted in self-sacrificial conduct on behalf of their sovereign and their country. It was the imperial household that made all of this possible, for the emperor was the incarnation of the selfless wisdom of the universe. It can therefore be said that Mahayana Buddhism didn't simply spread to Japan but was actually created there.22

Furukawa's final point concerning Bushido was that it was wrong to say that the samurai had disappeared at the time of the Meiji Restoration. On the contrary, all Japanese men became samurai at that time. Up to the Restoration, only members of the samurai class were allowed to carry weapons in order to fulfil their duty to protect their sovereign and the country. Now that duty had passed to all enfranchised citizens, and all Japanese men were now samurai, bound to uphold the code of Bushido.

As previously noted, Furukawa wrote the above in 1937, some ten years after Seisen published A Zen Primer and immediately preceding the outbreak of full-scale war with China. At that time all Japanese males were subject to military conscription. This was also a period marked by increasing tension between Japan and the United States and Britain, which, if only to protect their own economic interests in China and throughout Asia, were unwilling to ignore Japanese expansionism.

D. T. Suzuki It was against this backdrop that D. T. Suzuki once again entered the picture. By this time he-had written widely in both English and Japanese and established himself as a scholar of Buddhism in general, and Zen in particular. Suzuki had in fact begun to write about Zen in English as early as 1906, when his essay entitled "The Zen Sect of Buddhism" appeared in the Journal of the Pali Text Society. From this very first English-language effort, Suzuki sought to make his readers aware of the connection between Zen and Bushido, and the inspiration the combination of these two had provided Japan's victorious soldiers in the Russo-Japanese War:

The Lebensanschauung of Bushido is no more nor less than that of Zen. The calmness and even joyfulness of heart at the moment of death which is conspicuously observable in the Japanese, the intrepidity which is generally shown by the Japanese soldiers in the face of an overwhelming enemy; and the fairness of play to an opponent, so strongly taught by Bushido-all these come from the spirit of the Zen training, and not from any such blind, fatalistic conception as is sometimes thought to be a trait peculiar to Orientals.23

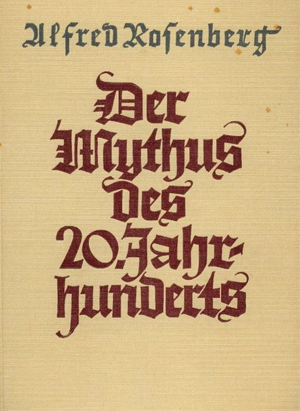

Despite this early effort, Suzuki did not make his best-known statement on the relationship of Zen and Bushido until 1938, when he published a book in English entitled Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. This work was later revised and republished in 1959 by Princeton University Press as Zen and Japanese Culture. Given the almost universal approval this work has met with over the years in both the United States and Europe, it is somewhat surprising to learn that Suzuki's description of the relationship between Zen and Bushido contained in three of this book's eleven chapters is basically a reiteration and elaboration of everything that had come before.

Suzuki began his description of the relationship between Zen and Bushido in the book's second chapter. He described the "rugged virility" of Japan's warriors versus the "grace and refinement" of Japan's aristocracy. He then stated: "The soldierly quality, with its mysticism and aloofness from worldly affairs, appeals to the will-power. Zen in this respect walks hand in hand with the spirit of Bushido ("Warriors' Way")."24 On the one hand, Suzuki claimed that "Buddhism ... in its varied history has never been found engaged in warlike activities." Yet in Japan, Zen had "passively sustained" Japan's warriors both morally and philosophically. They were sustained morally because "Zen is a religion which teaches us not to look backward once the course is decided." Philosophically, they were sustained because "[Zen] treats life and death indifferently."25

Suzuki was clearly taken with the idea of Zen as "a religion of the will."26 Over and over again he returned to this theme. For example: "A good fighter is generally an ascetic or stoic, which means he has an iron will. This, when needed, Zen can supply."27 Less than a page later, Suzuki went on to say: "Zen is a religion of will-power, and will-power is what is urgently needed by the warriors, though it ought to be enlightened by intuition."28

Together with his fascination with the relationship of Zen and willpower, Suzuki is attracted to the relationship between Zen discipline and the warrior:

Zen discipline is simple, direct, self-reliant, self-denying; its ascetic tendency goes well with the fighting spirit. The fighter is to be always single-minded with one object in view, to fight, looking neither backward nor sideways. To go straight forward in order to crush the enemy is all that is necessary for him.29

Although Suzuki first maintained that it was the Zen philosophy of "treat[ing] life and death indifferently" which had sustained Japan's warriors, he then went on to deny that Zen had any philosophy at all. He wrote:

Zen has no special doctrine or philosophy, no set of concepts or intellectual formulas, except that it tries to release one from the bondage of birth and death, by means of certain intuitive modes of understanding peculiar to itself. It is, therefore, extremely flexible in adapting itself to almost any philosophy and moral doctrine as long as its intuitive teaching is not interfered with. It may be found wedded to anarchism or fascism, communism or democracy, atheism or idealism, or any political or economic dogmatism. It is, however, generally animated with a certain revolutionary spirit, and when things come to a deadlock-as they do when we are overloaded with conventionalism, formalism, and other cognate isms - Zen asserts itself and proves to be a destructive force.30

Suzuki's statement that Zen could be found wedded to anarchism or communism is a fascinating comment, since Uchiyama Gudo and his fellow Buddhist priests had earlier attempted to accomplish something very much like that. For their efforts, of course, they were condemned by the leaders of the Soto and Rinzai Zen sects and the leaders of all other sects of Japanese Buddhism.

Perhaps what Suzuki was really trying to do in the above statement was justify the close relationship which by 1938 already existed between Zen and the Japanese military. Not only did Suzuki identify Zen as a "destructive force," but he also wrote favorably of the modern relationship among Zen, Bushido, and Japan's military actions in China:

There is a document that was very much talked about in connection with the Japanese military operations in China in the 1930s. It is known as the Hagakure, which literally means "Hidden under the Leaves," for it is one of the virtues of the samurai not to display himself, not to blow his horn, but to keep himself away from the public eye and be doing good for his fellow beings. To the compilation of this book, which consists of various notes, anecdotes, moral sayings, etc., a Zen monk had his part to contribute. The work started in the middle part of the seventeenth century under Nabeshima Naoshige, the feudal lord of Saga in the island of Kyushu. The book emphasizes very much the samurai's readiness to give his life away at any moment, for it states that no great work has ever been accomplished without going mad -- that is, when expressed in modern terms, without breaking through the ordinary level of consciousness and letting loose the hidden powers lying further below. These powers may be devilish sometimes, but there is no doubt that they are superhuman and work wonders. When the unconscious is tapped, it rises above individual limitations. Death now loses its sting altogether, and this is where the samurai training joins hands with Zen.31

As the following conclusion to the above makes clear, Suzuki was also very concerned with the warrior's ( and soldier's) use of Zen to "master death":

The problem of death is a great problem with everyone of us; it is, however, more pressing for the samurai, for the soldier, whose life is exclusively devoted to fighting, and fighting means death to fighters of either side .... It was therefore natural for every sober-minded samurai to approach Zen with the idea of mastering death.32

Another belief which Suzuki shared with his contemporaries was that Bushido was neither dead nor limited to imperial soldiers, the modern equivalent of Japan's traditional warriors:

The spirit of the samurai deeply breathing Zen into itself propagated its philosophy even among the masses. The latter, even when they are not particularly trained in the way of the warrior, have imbibed his spirit and are ready to sacrifice their lives for any cause they think worthy. This has repeatedly been proved in the wars Japan has so far had to go through.33

Finally, Suzuki could not avoid addressing the fundamental question of how the death and destruction caused by the samurai's sword could be related to Zen and Buddhist compassion. He therefore addressed two chapters (i.e., "Zen and Swordsmanship I" and "Zen and Swordsmanship II") to this very question. He began his discussion by noting what he considered to be the "double office" of the sword:

The sword has thus a double office to perform: to destroy anything that opposes the will of its owner and to sacrifice all the impulses that arise from the instinct of self-preservation. The one relates itself to the spirit of patriotism or sometimes militarism, while the other has a religious connotation of loyalty and self-sacrifice. In the case of the former, very frequently the sword may mean destruction pure and simple, and then it is the symbol of force, sometimes devilish force. It must, therefore, be controlled and consecrated by the second function. Its conscientious owner is always mindful of this truth. For then destruction is turned against the evil spirit. The sword comes to be identified with the annihilation of things that lie in the way of peace, justice, progress, and humanity.34

It is instructive to note here that the tenor of the preceding quote is quite similar to Suzuki's thesis in A Treatise on the New [Meaning of] Religion previously discussed. There he said:

The purpose of maintaining soldiers and encouraging the military arts is not to conquer other countries or deprive them of their rights or freedom .... The construction of big warships and casting of giant cannon is not to trample on the wealth and profit of others for personal gain. Rather, it is done only to prevent the history of one's country from being disturbed by injustice and outrageousness. Conducting commerce and working to increase production is not for the purpose of building up material wealth in order to subdue other nations. Rather, it is done only in order to develop more and more human knowledge and bring about the perfection of morality. Therefore, if there is a lawless country which comes and obstructs our commerce, or tramples on our rights, this is something that would truly interrupt the progress of all humanity. In the name of religion our country could not submit to this. Thus, we would have no choice but to take up arms, not for the purpose of slaying the enemy, nor for the purpose of pillaging cities, let alone for the purpose of acquiring wealth. Instead, we would simply punish the people of the country representing injustice in order that justice might prevail.35

Even more closely related to Suzuki's earlier quote are the sentiments of his master, Shaku Soen. It will be recalled that at the time of the Russo-Japanese War he said: "In the present hostilities, into which Japan has entered with great reluctance, she pursues no egotistic purpose, but seeks the subjugation of evils hostile to civilization, peace, and enlightenment."36 In any event, Suzuki's mental gymnastics on this issue did not stop with the above comments. He went on to directly address the seeming contradictions among Zen, the sword, and killing:

The sword is generally associated with killing, and most of us wonder how it can come into connection with Zen, which is a school of Buddhism teaching the gospel of love and mercy. The fact is that the art of swordsmanship distinguishes between the sword that kills and the sword that gives life. The one that is used by a technician cannot go any further than killing, for he never appeals to the sword unless he intends to kill. The case is altogether different with the one who is compelled to lift the sword. For it is really not he but the sword itself that does the killing. He had no desire to do harm to anybody, but the enemy appears and makes himself a victim. It is as though the sword performs automatically its function of justice, which is the function of mercy .... When the sword is expected to play this sort of role in human life, it is no more a weapon of self-defense or an instrument of killing, and the swordsman turns into an artist of the first grade, engaged in producing a work of genuine originality.37

Previous commentators, it will be recalled, have identified a Buddhist-sanctioned war as an act of compassion. As the above quotation makes clear, Suzuki agreed with this position. He further spoke with apparent approval of the Zen spirit manifested in Japan's military operations in China. Moreover, he clearly approved of a war "identified with the annihilation of things that lie in the way of peace, justice, progress, and humanity." But perhaps his most creative contribution to the discourse of his day was the assertion that the Zen-trained swordsman (and, by extension, the modern soldier) "turns into an artist of the first grade, engaged in producing a work of genuine originality."

Suzuki was, moreover, not simply interested in making his views on the relationship between Zen and the sword known outside of Japan. Less than one month before Pearl Harbor, on November 10, 1941, he joined hands with such military leaders as former army minister and imperial army general Araki Sadao (1877-1966), imperial navy captain Hirose Yutaka, and others to publish a book entitled The Essence of Bushido (Bushido no Shinzui). In his foreword, the book's editor, Handa Shin, explained the importance of Bushido: "It is Bushido that is truly the driving force behind the development of our nation. In the future, it must be the fundamental power associated with the great undertaking of developing Asia, the importance of which to world history is increasing day by day."38 Addressing the reason for publishing the book at that time, Handa said that the book's purpose would be accomplished "if our young men and boys find even a little something enticing in it."39

The connection of this book to the goals and purposes of the imperial military was unmistakable. The book's very first entry consisted of the Field Service Combatants' Code (Senjinkun), promulgated on January 8, 1941, by the army minister at the time, Tojo Hideki (1884-1948). The code, which all imperial army soldiers were required to memorize, had clear religious overtones, including such statements as "faith is power" and "duty is sacred."40 More important, the seventh section, entitled "View of Life and Death; read as if it had come directly from the hands of Suzuki, Shaku Soen, and others of similar views:

That which penetrates life and death is the lofty spirit of self-sacrifice for the public good. Transcending life and death, earnestly rush forward to accomplish your duty. Exhausting the power of your body and mind, calmly find joy in living in eternal duty.41

In addition, the book's final entry consisted of the 1932 "Essentials of the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors" (Gunjin Chokuyu Yogi), the original version of which had been promulgated by Emperor Meiji in 1882.

Suzuki's personal contribution, entitled simply "Zen and Bushido." consisted of a fourteen-page distillation of his earlier thought. It did not cover any new intellectual ground. Suzuki's favorite themes were present as always, including his oft-repeated assertion that "The spirit of Bushido is truly to abandon this life, neither bragging of one's achievements, nor complaining when one's talents go unrecognized. It is simply a question of rushing-forward toward one's ideal."42 The book's editor pointed out in his introduction to Suzuki's essay that "Dr. Suzuki's writings are said to have strongly influenced the military spirit of Nazi Germany."43

In this connection, it is interesting to note the comments made by the Japanese ambassador to Nazi Germany on September 27, 1940. Following the signing of the Tripartite Pact between Japan, Germany, and Italy, a reception was held in Hitler's chancellory in Berlin. In his congratulatory speech Ambassador Kurusu Saburo (1888-1954) said:

The pillar of the Spirit of Japan is to be found in Bushido. Although Bushido employs the sword, its essence is not to kill people, but rather to use the sword that gives life to people. Using the spirit of this sword, we wish to contribute to world peace.44

Whether by design or accident, Suzuki's sentiments as first expressed in 1938 had, two years later, become government policy or, perhaps more accurately, government rationalization.

Seki Seisetsu The Promotion of Bus hi do (Bushido no Koyo) was published in 1942, the year following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. It was a series of talks by Seki Seisetsu (1877-1945), a "fully enlightened" Zen master who served both as the head of the Tenryuji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect and as a military chaplain. A second Rinzai priest, Yamada Mumon (1900-1988), edited this work. After the war, Mumon, Seisetsu's disciple, became president of Hanazono University and chief abbot of the university's ecclesiastical sponsor, the Myoshinji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect.

One of the most striking features of Seisetsu's book is its cover, which depicts the Japanese fairy-tale hero Momotaro. Dressed in samurai clothing, Momotaro stands with his sword pinning down two devils, Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt. This representation is clearly a slightly humorous reflection of the wartime epithet, "the devilish Americans and English" (kichiku beiei).

Like so many of his predecessors, Seisetsu began his description of Bushido as "being nothing other than the Spirit of Japan." Zen had contributed its "profound and exquisite enlightenment" to Bushido, leading to the latter's "unique moral system." Thus had Bushido become "the precious jewel incorporating the purity of the spiritual culture of the Orient."45

In what was by now a familiar litany, Bushido was said to "prize military prowess and view death as so many goose feathers."46 Samurai "revered their sovereign and honored their ancestors."47 They also valued loyalty, frugality, simplicity, decorum, and benevolence. All of these values were identical with those of modern soldiers. Not only that, these values applied equally to "the people of this country who are now all soldiers, for I believe that every citizen ought to adhere to the Bushido of the present age."48

In his conclusion Seisetsu argued that the unity of Zen, the sword, and Bushido had only one goal: world peace. He wrote:

The true significance of military power is to transcend self-interest, to hope for peace. This is the ultimate goal of the military arts. Whatever the battle may be, that battle is necessarily fought in anticipation of peace. When one learns the art of cutting people down, it is always done with the goal of not having to cut people down. The true spirit of Bushido is to make people obey without drawing one's sword and to win without fighting. In Zen circles this is called the sword which gives life. Those who possess the sword that kills must, on the other hand, necessarily wield the sword which gives life.

From the Zen vantage point, where Manjushri [the bodhisattva of wisdom] has used his sharp sword to sever all ignorance and desire, there exists no enemy in the world. The very best of Bushido is to learn that there is no enemy in the world rather than to learn to conquer the enemy. Attaining this level, Zen and the sword become completely one, just as the Way of Zen and the Way of the Warrior [Bushido] unite. United in this way, they become the sublime leading spirit of society.

At this moment, we are in the sixth year of the sacred war, having arrived at a critical juncture. All of you should obey imperial mandates, being loyal, brave, faithful, frugal, and virile. You should cultivate yourselves more and more both physically and spiritually in order that you don't bring shame on yourselves as imperial soldiers. You should acquire a bold spirit like the warriors of old, truly doing your duty for the development of East Asia and world peace. I cannot help asking this of you.49

To the belief that Zen-sanctioned war was both just and compassionate, benefiting even one's enemy, must now be added the belief that it was all being done "for ... world peace." Like Shaku Soen (and many others) before him, Seisetsu also carried his message of peace and the unity of Zen and the sword to the battlefield on more than one occasion. One such visit took place in February 1938, when Seisetsu, accompanied by his disciple Yamada Mumon, made a sympathy calion General Terauchi Hisaichi (1879-1946) at his headquarters in northern China. More will be said about the relationship between Seisetsu and Terauchi in chapter 10.

ZEN AND THE IMPERIAL MILITARY

The reader will recall that one of the chief goals of the so-called New Buddhism of the late Meiji period was to prove its loyalty to the throne. This theme was further developed by the noted Buddhist scholar Yabuki Keiki (1879-1939), who wrote in 1934 that Buddhism had the potential "to become a most effective instrument for the state."50 In 1943 a Western scholar of Japanese religion, D. C. Holtom, emphasized that "Buddhism fosters the qualities of spirit that make for strong soldiers."51

If the preceding statements held true for institutional Buddhism as a whole, it should now be clear that they were particularly relevant to the Zen school. Leading Zen figures made unsurpassed efforts to foster loyalty to the emperor and make spiritually strong soldiers. Did anyone notice? That is to say, was the imperial military actually influenced by their words and actions?

A quantitative answer to this question, it must be admitted, is almost certainly beyond the realm of historical research. How would one accurately determine, more than fifty. years after the end of the war, either the extent or depth of such influence? This said, it is important to note that the imperial military, the imperial army in particular, was more than merely receptive to the type of Buddhist support described above. It actively solicited that support.

As previously discussed, the military had cooperated with frontline visits by Buddhist priests like Shaku Soen as early as the Russo-Japanese War. From that war Japanese military leaders such as General Hayashi Senjuro had come to realize just how critical spirit was in overcoming a better equipped and numerically superior enemy. In his book The Way of the Heavenly Sword, Leonard Humphreys explained it as follows:

The overriding lesson of the [Russo-Japanese J war appeared to be the decisive role of morale or spirit in combat. Japan's centuries-old samurai tradition had strongly emphasized the importance of the intangible qualities of the human spirit (seishin) in warfare, and this war served to reestablish their primacy. Since spirit was the universally acclaimed key to Japan's victory, the leadership tended to emphasize the irrational quality seishin and rest content with attained levels in the rational elements of war technology and its practical utilization through organization and training. After fifty years of borrowing from the West, the Army, like the people, was now relieved and proud to find new relevance in the nation's traditional values. . . . The sole key to victory lay in Yamatodamashii [Spirit of Japan].52

Based on this belief, the army proceeded between 1908 and 1928 to issue a number of changes to its standing orders. Each new military handbook or field manual placed increasing emphasis on developing military spirit, while actively promoting Bushido as the epitome of that spirit.

One example of this was the new infantry field manual issued in 1909, which made the infantry attack with small-arms fire, followed by a bayonet charge, the imperial army's chief tactical doctrine. This placed the burden for attaining victory on the infantry. Technology was thereby relegated to a secondary role, while the development of an irresistible attack spirit became paramount. A critical part of this spirit was absolute and unquestioning obedience to one's superiors, who acted on behalf of the emperor. Through training, this spirit of obedience had to transcend mere habit and become instinctive, unthinking.

In 1928 a revised The Essential Points of Supreme Command (Tosui Koryo) was issued. The continued emphasis on spirit as superior to material in combat resulted in the deletion in this revision of such words as "surrender." "retreat." and "defense." In addition, the term emperor's army, or kogun, was used officially for the first time. Each infantryman's rifle had the imperial chrysanthemum seal stamped on its barrel and was regarded as a precious, even holy gift from the emperor himself. For this reason, it must never, ever, be allowed to fall into enemy hands.

The year 1928 also marked the debut of a series of books and pamphlets devoted exclusively to developing the military spirit. The first, issued by the Inspectorate General of Military Training, was entitled simply A Guide to Spiritual Training (Seishin Kyoiku no Sanko). This was followed in 1930 by the two-volume The Moral Character of Military Men (Bujin no Tokuso). These works opened a floodgate of both official and unofficial materials written on this topic during the 1930S. Needless to say, Zen-related figures were anxious to have their say.

As we have seen, an earlier popular Buddhist commentator on Bushido, Furukawa Taigo, had identified himself as being engaged "in spiritual training for army officer candidates." This training program was focused chiefly on the officer corps. Cadets were first exposed to it at the military preparatory school level and then further indoctrinated during their eighteen months at the military academy. How effective was this spiritual training? A study by historian Mark Peattie caused him to rate it quite highly. "With the possible exception. of the pre-World War I French army." he wrote, "no other army articulated such an extreme code of sacrifice in the attack."53

The writings of one military officer, Lieutenant Colonel Sugimoto Gora (1900-1937), clearly indicate the type. of soldier this training produced and are a powerful testimonial to the influence that Bushido, incorporating the alleged unity of Zen and the sword, had on both imperial soldiers and the general public. Lieutenant Colonel Gora was destined, albeit posthumously, to become widely known and honored as a "god of war" (gunshin).