The Postwar Zen Responses to Imperial-Way Buddhism, Imperial-State Zen, and Soldier Zen, Chapter Ten, [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

Second Edition

© 2006 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

PART III: POSTWAR TRENDS

CHAPTER TEN: THE POSTWAR ZEN RESPONSES TO IMPERIAL-WAY BUDDHISM, IMPERIAL-STATE ZEN, AND SOLDIER ZEN

Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, marked the end of imperial-way Buddhism, imperial-state Zen, and soldier Zen. In the wake of Japan's defeat and the Allied Occupation, the sects of institutional Buddhism quickly changed aspects of their daily liturgies to reflect the demise of these movements. Buddhist leaders were faced with the question of how to explain their wartime conduct. Had their actions been a legitimate expression of Buddha Dharma or a betrayal of it?

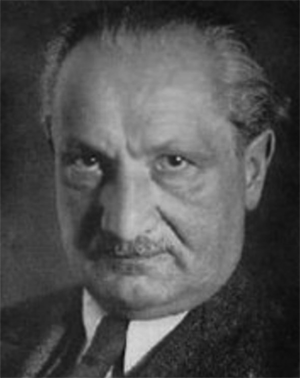

D. T. SUZUKI'S RESPONSE

D. T. Suzuki was probably the first Buddhist leader in the postwar period to address the moral questions related to Buddhist war support. He first broached the topic of Buddhist war responsibility in October 1945, in a new preface for a reprint of Japanese Spirituality (Nihonteki Reisei), originally published in 1944. He began by assigning to Shinto the blame for providing the "conceptual background" to Japanese militarism, imperialism, and totalitarianism. He then went on to discuss the Buddhist role as follows:

It is strange how Buddhists neither penetrated the fundamental meaning of Buddhism nor included a global vision in their mission. Instead, they diligently practiced the art of self-preservation through their narrow-minded focus on "pacifying and preserving the state." Receiving the protection of the politically powerful figures of the day, Buddhism combined with the state, thinking that its ultimate goal was to subsist within this island nation of Japan.

As militarism became fashionable in recent years, Buddhism put itself in step with it, constantly endeavouring not to offend the powerful figures of the day. Out of this was born such things as totalitarianism, references to [Shinto] mythology, "imperial-way Buddhism," and so forth. As a result, Buddhists forgot to include either a global vision or concern for the masses within the duties they performed. In addition, they neglected to awake within the Japanese religious consciousness the philosophical and religious elements, and the spiritual awakening, that are an intrinsic part of Buddhism.

Although it may be said that Buddhism became "more Japanese" as a result of the above, the price was a retrogression in terms of Japanese spirituality itself. That is to say, the opportunity was lost to develop a world vision within Japanese spirituality that was sufficiently extensive or comprehensive.1

Suzuki also attached a large portion of the blame for the militarization of Zen to both Zen priests and the Zen establishment. In an article written in 1946 fox the magazine Zengaku Kenkyu entitled "Renewal of the Zen World" (Zenkai Sasshin), Suzuki called for a "renewal" of Japanese Zen: "Generally speaking, present-day Zen priests have no knowledge or learning and therefore are unable to think about things independently or formulate their own independent opinions. This is a great failing of Zen priests."2 One result of this "great failing" had been Zen's collaboration with the war, including mouthing government propaganda during wartime and then suddenly embracing world peace and democracy in the postwar era. As far as Suzuki was concerned, "it would be justifiable for priests like these to be considered war criminals."3

Interestingly, Suzuki did not deny that the Zen priests he criticized were enlightened, but rather that being enlightened was no longer sufficient for Zen priests:

With satori [enlightenment] alone, it is impossible [for Zen priests] to shoulder their responsibilities as leaders of society. Not only is it impossible, but it is conceited of them to imagine they could do so. . . . In satori there is a world of satori. However, by itself satori is unable to judge the right and wrong of war. With regard to disputes in the ordinary world, it is necessary to employ intellectual discrimination .... Furthermore, satori by itself cannot determine whether something like communism's economic system is good or bad.4

One reason Suzuki gave for this regrettable state of affairs was that Zen had developed under the "oppression" of a feudal society and had been forced to utilize that oppression in order to advance its own interests. It is only human nature, Suzuki pointed out, "to lick the hand that feeds you."5 In addition, Japanese Zen priests had failed to realize that a world existed outside of their own country. Suzuki concluded his article as follows:

In any event, today's Zen priests lack "intellectuality" (J. chisei) .... I wish to foster in Zen priests the power to increasingly think about things independently. A satori which lacks this element should be taken to the middle of the Pacific Ocean and sent straight to the bottom! If there are those who say this can't be done, those persons should confess and repent all of the ignorant and uncritical words they and others spoke during the war in their temples and other public places.6

In all the passages above Suzuki seems to except himself from the need to confess or repent, but in the preface to Japanese Spirituality, he alludes obliquely to his own responsibility: "I believe that a major reason for Japan's collapse was truly because each one of us lacked an awareness of Japanese spirituality."7 If Suzuki accepts any personal responsibility for Japan's collapse, it is responsibility shared equally with each and every Japanese.

Suzuki apparently regarded his active promotion of the unity of Zen and the sword, the unity of Zen and Bushido, as having had no connection to Japan's militarism, and he had very little to say about the possibility that any of his wartime writings may have influenced the course of events. He did, however, refer rather mysteriously to a deficiency in Japanese Spirituality: "This work was written before Japan's unconditional surrender to the Allies. I was therefore unable to give clear expression to the meaning of Japanese spirituality."8 Is Suzuki suggesting that he distorted or censored his own writings in order to publish them under Japan's military government? Apparently not, since later in the same preface he explains the lack of clarity was due to the book's "academic nature," coupled with its "extremely unorganized structure."

Suzuki spoke again of his own moral responsibility for the war in The Spiritualizing of Japan (Nihon no Reiseika), published in 1947. This book is a collection of five lectures that he had given at Shin sect-affiliated Otani University in Kyoto during the month of June 1946. The focus of his talks was Shinto, for by this time he had decided that Shinto was to blame for Japan's militaristic past. According to Suzuki, Shinto was a "primitive religion" that "lacked spirituality." These factors had led to Japan's "excessive nationalism" and "military control."9 The solution to this situation was, in Suzuki's eyes, quite simple: "do away with Shinto."10 But Suzuki also spoke of his own responsibility for events:

This is not to say that we were blameless. We have to accept a great deal of blame and responsibility .... Both before and after the Manchurian Incident [of 1931] all of us applauded what had transpired as representing the growth of the empire. I think there were none amongst us who opposed it. If some were opposed, I think they were extremely few in number. At that time everyone was saying we had to be aggressively imperialistic. They said Japan had to go out into the world both industrially and economically because the country was too small to provide a living for its people. There simply wasn't enough food; people would starve.

I have heard that the Manchurian Incident was fabricated through various tricks. I think there were probably some people who had reservations about what was going on, but instead of saying anything they simply accepted it. To tell the truth, people like myself were just not very interested in such things.11

Even in the midst of Japan's utter defeat, Suzuki remained determined to find something praiseworthy in Japan's war efforts. He described the positive side of the war as follows:

Through the great sacrifice of the Japanese people and nation, it can be said that the various peoples of the countries of the Orient had the opportunity to awaken both economically and politically. . .. This was just the beginning, and I believe that after ten, twenty, or more years the various peoples of the Orient may well have formed independent countries and contributed to the improvement of the world's culture in tandem with the various peoples of Europe and America.12

Here, in an echo of his wartime writings, Suzuki continued to praise the "great sacrifice" the Japanese people allegedly made to "awaken the peoples of Asia."

To his English-reading audience, Suzuki offered a different interpretation of the war. The following appeared in an essay entitled ''An Autobiographical Account." included in the commemorative anthology A Zen Life: D. T. Suzuki Remembered:

The Pacific War was a ridiculous war for the Japanese to have initiated; it was probably completely without justification. Even so, seen in terms of the phases of history, it may have been inevitable. It is undeniable that while British interest in the East has existed for a long time, interest in the Orient on the part of Americans heightened as a consequence of their coming to Japan after the war, meeting the Japanese people, and coming into contact with various Japanese things.13

Added to the awakening of the peoples of Asia, Suzuki tells us that another positive side bf the "inevitable" war was the increased American presence and interest in Japan. In sum, it would seem that both friend and foe alike benefited in some way from Japan's "great sacrifice."

It is also noteworthy that Suzuki did not find war itself "ridiculous" but only the Pacific War, which was "probably" unjustified. Nowhere in Suzuki's writings does one find the least regret, let alone an apology, for Japan's earlier colonial efforts in such places as China, Korea, or Taiwan. In fact, he was quite enthusiastic about Japanese military activities in Asia. In an article addressed specifically to young Japanese Buddhists written in 1943 he stated: ''Although it is called the Greater East Asia War, its essence is that of an ideological struggle for the culture of East Asia. Buddhists must join in this struggle and accomplish their essential mission."14 One is left with the suspicion that for Suzuki things really didn't go wrong until Japan decided to attack the United States. What was it that made this particular war so "ridiculous"?

I suggest the answer is that Suzuki, having previously lived for more than a decade in the United States, knew Japan would be defeated. In support of this conclusion I point to a guest lecture Suzuki presented at Kyoto University in September 1941, just three months before Pearl Harbor. His ostensible topic was "Zen and Japanese Culture." but after finishing the formal part of his presentation, Suzuki added:

Japan must evaluate more calmly and accurately the awesome reality of America's industrial productivity. Present-day wars will no longer be determined as in the past by military strategy and tactics, courage and fearlessness alone. This is because of the large role now played by production capacity and mechanical power.15

Some observers, including Suzuki's former student Hidaka Daishiro, who recorded these remarks, interpret them as "antiwar" statements. Another way to view them is as simple common sense, without any moral or political intent: Don't pick a fight with someone you can't beat! Suzuki did not continue to make such statements of common sense after Pearl Harbor, when Japan had already engaged the United States in combat. Much more important, however, is the fact that he never criticized Japan's long-standing aggression against the peoples of Asia. Suzuki thought that punishing the "unruly heathens" was all right as long as Japan was strong enough to do so.

DECLARATIONS OF WAR RESPONSIBILITY BY JAPANESE BUDDHIST SECTS

In the postwar years there have only been four declarations addressing war responsibility or complicity by the leaders of traditional Buddhist sects in Japan's war effort. None of these statements was issued until more than forty years after the end of the war. By comparison, Japan's largest Protestant organization first issued a statement, "A Confession of Responsibility During World War II by the United Church of Christ in Japan," in 1967, twenty years before any Buddhists spoke up-though even that statement was more than a generation in the making. Most leading Japanese Buddhist sects remain silent to this day. None of the branches of the Rinzai Zen sect, for example, has formally addressed this crucial issue, which institutional Japanese Buddhism is only beginning to face.

The first of the four Buddhist sects to make an admission of war responsibility was the Higashi Honganji branch of the Shin sect in 1987. Koga Seiji, administrative head of the branch, read the statement aloud as part of a "Memorial Service for All War Victims" held on April 2, 1987. It read in part:

As we recall the war years, it was our sect that called the war a "sacred war." It was we who said, "The heroic spirits [of the war dead] who have been enshrined in [Shinto's] Yasukuni Shrine have served in the great undertaking of guarding and maintaining the prosperity of the imperial throne. They should therefore to be revered for having done the great work of a bodhisattva ." This was an expression of deep ignorance and shamelessness on our part. When recalling this now, we are attacked by a sense of shame from which there is no escape ....

Calling that war a sacred war was a double lie. Those who participate in war are' both victims and victimizers. In light of the great sin we have committed, we must not pass it by as being nothing more than a mistake. The sect declared that we should revere things that were never taught by Saint [Shinran]. When we who are priests think about this sin, we can only hang our heads in silence before all who are gathered here.16

The Nishi Honganji branch followed suit four years later, in 1991. The following statement was issued by the administrative assembly of the Nishi Honganji branch on February 27, 1991. It was entitled "The Resolution to Make Our Sect's Strong Desire for Peace Known to All in Japan and the World." The central focus of this declaration, however, was the Gulf War coupled with the question of nuclear warfare mentioned in the second and third paragraphs. The sect's own wartime role did not rate mention until the fourth paragraph:

Although there was pressure exerted on us by the military-controlled state, we must be deeply penitent before the Buddhas and patriarchs, for we ended up cooperating with the war and losing sight of the true nature of this sect. This can also be seen in the doctrinal sphere, where the [sect's] teaching of the existence of relative truth and absolute truth was put to cunning use.17

In 1992 the Soto sect published a "Statement of Repentance" (sanshabun) apologizing for its wartime role. If the Rinzai Zen sect has been unwilling to face its past, it cannot be claimed that the postwar leadership of the Soto Zen sect was any more anxious to do so. Yet, a series of allegations concerning human rights abuses by this sect had the cumulative effect of forcing it to do so in spite of its reluctance. Unquestionably, the single most important event in this series of allegations was the sect headquarters' publication in 1980 of The History of the Soto Sect's Overseas Evangelization and Missionary Work (Soto Shu Kaigai Kaikyo Dendo Shi).

In the January 1993 issue of Soto Shuho, the sect's administrative headquarters announced that it was recalling all copies of the publication:

The content of this book consists of the history of the overseas missionary work undertaken by this sect since the Meiji period, based on reports made by the persons involved. However, upon investigation, it was discovered that this book contained many accounts that were based on discriminatory ideas. There were, for example, words which discriminated against peoples of various nationalities. Furthermore, there were places that were filled with uncritical adulation for militarism and the policy to turn [occupied peoples] into loyal imperial subjects.18

Immediately following the above announcement was the Statement of Repentance issued by the administrative head of the sect, Otake Myogen. The statement contained a passage which clearly shows how the preceding work served as a catalyst for what amounted to the sect's condemnation of its wartime role. The statement's highlights are as follows:

We, the Soto sect, have since the Meiji period and through to the end of the Pacific War, utilized the good name of overseas evangelization to violate the human rights of the peoples of Asia, especially those in East Asia. This was done by making common cause with, and sharing in, the sinister designs of those who then held political power to rule Asia. Furthermore, within the social climate of ceasing to be Asian and becoming Western, we despised the peoples of Asia and their cultures, forcing Japanese culture on them and taking actions which caused them to lose their national pride and dignity. This was all done out of a belief in the superiority of Japanese Buddhism and our national polity. Not only that, but these actions, which violated the teachings of Buddhism, were done in the name of Buddha Shakyamuni and the successive patriarchs in India, China, and Japan who transmitted the Dharma. There is nothing to be said about these actions other than that they were truly shameful.

We forthrightly confess the serious mistakes we committed in the past history of our overseas missionary work, and we wish to deeply apologize and express our repentance to the peoples of Asia and the world.

Moreover, these actions are, not merely the responsibility of those people who were directly involved in overseas missionary work. Needless to say, the responsibility of the entire sect must be questioned inasmuch as we applauded Japan's overseas aggression and attempted to justify it.

To make matters worse, the Soto sect's publication in 1980 of the History of the Soto Sect's Overseas Evangelization and Missionary Work was done without reflection on these past mistakes. This meant that within the body of the work there were not only positive evaluations of these past errors, but even expressions which attempted to glorify and extol what had been done. In doing this, there was a complete lack of concern for the pain of the peoples of Asia who suffered as a result. The publication involved claimed to be a work of history but was written from a viewpoint which affirmed an imperial view of history, recalling the ghosts of the past and the disgrace of Japan's modern history.

We are ashamed to have published such a work and cannot escape a deeply guilty conscience in that this work was published some thirty-five years after the end of the Pacific War. The reason for this is that since the Meiji period our sect has cooperated in waging war, sometimes having been flattered into making common cause with the state, and other times rushing on its own to support state policies. Beyond that, we have never reflected on the great misery that was forced upon the peoples of Asia nor felt a sense of responsibility for what happened.

The historian E. H. Carr has said: "History is an endless conversation between the past and the present." Regretfully, our sect has failed to engage in that conversation, with the result that we have arrived at today without questioning the meaning of the past for the present, or verifying our own standpoint in the light of past history. We neglected to self-critically examine our own war responsibility as we should have done immediately after having lost the war in 1945.

Although the Soto sect cannot escape the feeling of being too late, we wish to apologize once again for our negligence and, at the same time, apologize for our cooperation with the war .... We recognize that Buddhism teaches that all human beings are equal as children of the Buddha. And further, that they are living beings with a dignity that must not, for any reason whatsoever, be impaired by others. Nevertheless, our sect, which is grounded in the belief of the transference of Shakyamuni's Dharma from master to disciple, both supported and eagerly sought to cooperate with a war of aggression against other peoples of Asia, calling it a holy war.

Especially in Korea and the Korean peninsula, Japan first committed the outrage of assassinating the Korean Queen [in 1895], then forced the Korea of the Lee Dynasty into dependency status [in 1904-5), and finally, through the annexation of Korea [in 1910), obliterated a people and a nation. Our sect acted as an advance guard in this, contriving to assimilate the Korean people into this country, and promoting the policy of turning Koreans into loyal imperial subjects.

All human beings seek a sense of belonging. People feel secure when they have a guarantee of their identity deriving from their own family, language, nationality, state, land, culture, religious belief, and so forth. Having an identity guarantees the dignity of human beings. However, the policy to create loyal imperial subjects deprived the Korean people of their nation, their language, and, by forcing them to adopt Japanese family and personal names, the very heart of their national culture. The Soto sect, together with Japanese religion in general, took upon itself the role of justifying these barbaric acts in the name of religion.

In China and other countries, our sect took charge of pacification activities directed towards the peoples who were the victims of our aggression. There were even some priests who took the lead in making contact with the secret police and conducting spying operations on their behalf.

We committed mistakes on two levels. First, we subordinated Buddhist teachings to worldly teachings in the form of national policies. Then we proceeded to take away the dignity and identity of other peoples. We solemnly promise that we will never make these mistakes again ....

Furthermore, we deeply apologize to the peoples of Asia who suffered under the past political domination of Japan. We sincerely apologize that in its overseas evangelism and missionary work the Soto sect made common cause with those in power and stood on the side of the aggressors.19

Of all the Japanese Buddhist sects to date, the Soto sect's statement of apology is certainly the most comprehensive. Yet, it almost totally ignores the question of the doctrinal and historical relationship between Buddhism and the state, let alone between Buddhism and the emperor. Is, for example, "nation-protecting Buddhism" an intrinsic part of Buddhism or merely a historical accretion? Similarly, is the vaunted unity between Zen and the sword an orthodox or heretical doctrine? Is there such a thing as a physical "life-giving sword" or is it no more than a Zen metaphor that Suzuki and others have terribly misused?

The most recent statement by a Japanese Buddhist sect concerning its wartime role was issued on June 8, 1994 by the Jimon branch of the Tendai sect, the smallest of that sect's three branches. Its admission of war responsibility amounted to one short phrase contained in "An Appeal for the Extinction of Nuclear [Weapons)." It read: "Having reached the fiftieth anniversary of the deaths of the atomic bomb victims, we repent of our past cooperation and support for [Japan's) war of aggression."20

In spite of the positive good that has issued from the Soto sect's statement of apology, including the posthumous reinstatement of the priestly status of Uchiyama Gudo in 1983, Zen scholars such as Ichikawa Hakugen make it clear that the rationale for Zen's support of state-sponsored warfare in general, and Japanese militarism in particular, is far more deeply entrenched in Zen and Buddhist doctrine and historicaL practice, especially in its Mahayana form, than any Japanese Buddhist sect has yet to publicly admit.

ICHIKAWA HAKUGEN AND OTHER COMMENTATORS

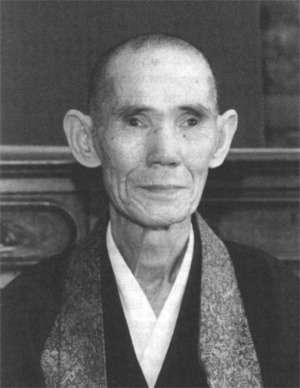

Far more has been written on the relationship of the Zen school to war than on any other school or sect of Japanese Buddhism. This is due to the voluminous writings of one man, the late Zen scholar and former Rinzai Zen priest, Ichikawa Hakugen (1902-86). In the postwar years he almost singlehandedly brought this topic before the public and made it into an area of scholarly research. His writing, in turn, has sparked further investigation of this issue within other sects as well.

Before examining Ichikawa's writings, however, it would be helpful to look at comments made by other Zen adherents to get some idea of the overall tenor of the discussion and to bring the breadth and depth of Ichikawa's contribution into clearer focus. Several Zen scholars after Ichikawa continued to pursue this theme, coming to some remarkable conclusions, and a review of their writings closes out this chapter.

Yanagida Seizan Yanagida Seizan (b. 1922) started life as the son of a Rinzai Zen priest in a small village temple in Shiga Prefecture. As an adult he became the director of the Institute for Humanistic Studies at Kyoto University. Following retirement, he founded and became the first director of the International Research Institute f~r Zen Buddhism located at Hanazono University. In 1989 he presented a senes of lectures on Zen at both Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1990 Seizan published a book entitled Zen from the Future (Mirai kara no Zen). This book, containing a number of lectures he had presented in the United States, included material that was both personal and confessional in nature, making it relatively unusual among Zen scholarship. In the book Seizan speaks of his experience as a young Rinzai Zen priest during and immediately after the war:

When as a child I began to become aware of what was going on around me, the Japanese were fighting neighboring China. Then the war expanded to the Pacific region, and finally Japan was fighting the rest of the world. When Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, I had experienced two major wars. As someone who was brought up while these wars were expanding, I did not have the luxury of thinking deeply about the relationship between the state as a sovereign power engaged in war and Zen Buddhism. No doubt this was largely due to the fact that I had neither the opportunity to go to the battlefield nor directly engage in battle. Furthermore, having been brought up in a remote Zen temple, I was completely ignorant of what was happening in the world. In the last phase of World War II, I was training as a Zen monk at Eigenji, proud of being away from the secular world and convinced that my total devotion to Zen practice would serve the state.

At any rate, with Japan's defeat I became aware of my own stupidity for the first time, with the result that I developed a deep sense of self-loathing. From 1945 to 1950 I did not see any point to human life, and I was both mentally and physically in a state of collapse. I had lost many of my friends; I alone had been left behind. We had fought continuously against China, the home country of Zen. We had believed, without harboring the slightest doubt, that it was a just war. In a state of inexpressible remorse, I could find rest neither physically nor mentally, and day after day I was deeply disturbed, not knowing what to do.

There is no need to say how complete is the contradiction between the Buddhist precepts and war. Yet, what could I, as a Buddhist, do for the millions upon millions of my fellow human, beings who had lost their lives in the war? At that time, it dawned on me for the first time that I had believed that to kill oneself on the state's behalf is the teaching of Zen. What a fanatical idea!

All of Japan's Buddhist sects-which had not only contributed to the war effort but had been one heart and soul in propagating the war in their teachings-flipped around as smoothly as one turns one's hand and proceeded to ring the bells of peace. The leaders of Japan's Buddhist sects had been among the leaders of the country who had egged us on by uttering big words about the righteousness [of the war]. Now, however, these same leaders acted shamelessly, thinking nothing of it. Since Japan had turned itself into a civilized [i.e., democratic] nation overnight, their actions may have been unavoidable. Still, I found it increasingly difficult to find peace within myself. I am not talking about what others should or should not have done. My own actions had been unpardonable, and I repeatedly thought of committing suicide.21

Seizan did not, of course, commit suicide, but it is bracing to meet a Japanese Buddhist who was so moved by his earlier support for the war that he entertained the idea of killing himself. The irony is that by comparison with the numerous Zen and other Buddhist leaders we have heard from so far, Seizan bore very little responsibility for what had happened. Yet in the idealism of youth he felt obliged to take the sins of his elders on his own shoulders. He neither sought to ignore what had happened nor place the blame on anyone else.

Seizan's disdain for the way in which the previously prowar leaders of the various sects had so abruptly abandoned their war cries and become "peacemakers." coupled with his overall dissatisfaction with Rinzai Zen war collaboration, led him to stop wearing his robes in 1955:

I recognized that the Rinzai sect lacked the ability to accept its [war] responsibility. There was no hope that the sect could in any meaningful way repent of its war cooperation .... Therefore, instead of demanding the Rinzai sect do something it couldn't do, I decided that I should stop being a priest and leave the sect .... As far as . I'm concerned, [Zen] robes are a symbol of war responsibility. It was those robes that affirmed the war. I never intend to wear them again."22

Seizan's return to lay life did not, however, signal a lessening of his interest in Zen, for he became one of Japan's preeminent contemporary scholars of Buddhism, earning an international reputation for his research into the early development of Chinese Zen, or Chan Buddhism.

Masanaga Reiho Ichikawa Hakugen recorded numerous statements made by these instant converts to peace, Masanaga Reiho prominent among them. During the war, as we noted earlier, Reiho extolled the virtues of Japan's kamikaze pilots. On September 15, 1945, exactly one month after Japan's surrender, Reiho wrote the following:

The cause of Japan's defeat ... was that among the various classes within our country there were not sufficient capable men who could direct the war by truly giving it their all .... That is to say, we lacked individuals who, having transcended self-interest, were able to employ the power of a life based on moral principles .... It is religion and education that have the responsibility to develop such_ individuals ....

We must develop patriotic citizens who understand [the Zen teaching] that both learning and wisdom must be united with practice. They will become the generative power for the revival of our people . . . and we will be able to preserve our glorious national polity .... It is for this reason that religionists, especially Buddhists, must bestir themselves.23

In peace as well as war, it would seem, the national polity required Buddhists to bestir themselves. Reiho certainly did. He became vice-president of Komazawa University.

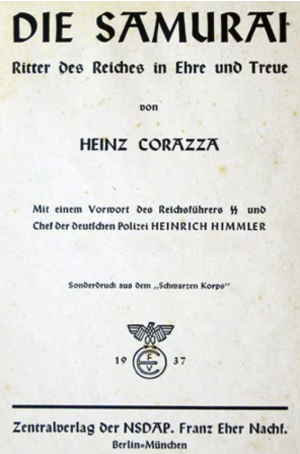

Yamada Mumon Rinzai Zen master Yamada Mumon was the editor in 1942 of the strongly prowar book by his teacher Seki Seisetsu entitled The Promotion of Bus hi do. As already noted, in postwar Japan Mumon became both president of Hanazono University and chief abbot of Myoshinji, the largest branch of the Rinzai Zen sect.

In 1964 a collection of Mumon's sayings was published in English under the title A Flower in the Heart. Although Mumon did not intend it to be a scholarly work, he nevertheless made some noteworthy observations about both modern Buddhist history and Japan's participation in the Pacific War:

The only time when Buddhism in Japan met a suppression by the hand of a government was during the Meiji Restoration. Then, its ' teachings were denounced and its sacred images desecrated. Only the desperate efforts of its leaders saved it from the fate of an utter extinction, but the price they had to pay for its survival was high, for the monks, they agreed, would take up arms at the time of national emergencies. The dealing was surely regrettable. If those celebrated priests of the Meiji era were deceived by the name of loyalty and patriotism, we of today were taken in by the deceitful name of holy war. As a consequence, the nation we all loved lost its gear and turned upside down. This teaches us that we must beware not so much of oppression as of compromise.24

Interestingly, Mumon described the events from what is basically a third party's point of view. Nowhere does he take personal responsibility for what happened. Later, however, he did broach this topic:

For a long time I have entertained a wish to build a temple in every Asian nation to which we caused so much indescribable sufferings and damages during the past war, as token of our sincere penitence and atonement, both to mourn for their deads and ours and to pray for a perpetual friendship between her and our country and for further cultural intercourses.25 [English as in original]

Here Mumon does at least admit to a collective responsibility for what happened, though he still does not discuss any personal role. Later, however, Mumon tries to justify the war, at least to some degree:

The sacrifices listed above were the stepping stones upon which the South-East Asian peoples could obtain their political independence. In a feeble sense, this war was a holy war. Is this observation too partial? ... "If it were for the sake of the peace of the Far East." a phrase in one of the war-time songs, still rings in my ears.26

In the face of all these contradictions, it is difficult indeed to identify Mumon's true views. This is made even more challenging by a subsequent statement made in Japanese and distributed at the inaugural meeting of the "Association to Repay the Heroic Spirits [of Dead Soldiers]" (Eirei ni Kotaeru Kai) on June 22, 1976. Mumon was one of the founders of this association, whose purpose was to lobby the Japanese Diet for reinstatement of state funding for Yasukuni Shrine, the Shinto .shrine in Tokyo dedicated to the veneration of the "heroic spirits" of Japan's war dead. Mumon's statement was entitled "Thoughts on State Maintenance of Yasukuni Shrine." It contained the following passage:

Japan destroyed itself in order to grandly give the countries of Asia their independence. I think this is truly an accomplishment worthy of the name "holy war." All of this is the result of the meritorious deeds of two million five hundred thousand heroic spirits in our country who were loyal, brave, and without rival. I think the various peoples of Asia who achieved their independence will ceaselessly praise their accomplishments for all eternity.27

To his English-speaking audience Mumon described the war as having been in some "feeble sense" a holy war. To his Japanese audience, however, he invokes "meritorious deeds." "heroic spirits." and the "ceaseless praise" of a Southeast Asia liberated by the Japanese imperial forces. Now the real Mumon speaks up-at least to his Japanese audience. In the introduction to A Flower in the Heart, Umehara Takeshi described Mumon as "one of those rare monks from whose presence emanates a sense of genuine holiness." 28 Questions of "genuine holiness" aside, Mumon clearly persisted in his belief in Japan's holy war even into the postwar period, a belief that has been a credo for conservative Japanese politicians to this day.

Asahina Sagen Asahina Sogen (1891-1979) was the chief abbot and administrative head of the Engakuji branch of the Rinzai Zen sect. It will be recalled that Shaku Soen had earlier been the abbot of this same temple, and though Sogen had never been his disciple, their thinking was quite similar. Furthermore, like Yamada Mumon, Sogen was active in conservative causes in the postwar years, most notably as one of the founders of the ''Association to Protect Japan" (Nihon o Mamoru Kai).

In 1978 Sogen published a book entitled Are You Ready? (Kakugo wa Yoi ka), the last part of which was autobiographical in nature and included extensive comments about the war, its historical background, and his own role in it. Sogen began his discussion, as so many others had, by praising the thirteenth-century military ruler Hojo Tokimune and his Chinese Zen master Mugaku Sogen. According to Sogen, the roots of both Zen involvement in prayer services and the subsequent dose relationship between Zen and the state can be traced back to this period:

The reason that Japanese Zen began to chant sutras in both morning and evening services was due to the Mongol invasion. Although other temples were making a big fuss of their prayers [to protect the country], Zen priests were only doing zazen. They were out of step [with the other sects] and said to be indifferent to the affairs of state. The result was that they began to recite sutras.29

Jumping more than six hundred years to the nineteenth century, Sogen wrote that the Sino-Japanese War had been caused by China, which tried "to put Japan under its thumb" in Korea.30 The subsequent Russo-Japanese War was, in his opinion, due entirely to Russian actions. "Russia rapidly increased its armaments and intended to destroy Japan without fighting. It was decided that if Japan was going to be destroyed without fighting, it might as well have a go at it and be destroyed."31

These remarks were only a warm-up for Sogen's lengthy discussion of the Pacific War. He began this discussion with the following comments:

Shortly after the [Pacific] War started, I realized that this was one we were going to lose. That is to say, the civil and military officials of whom the Japanese were so proud had turned into a totally disgusting bunch ....

I'm not going to mince words-the top-level leadership of the navy was useless. I know because living in Kamakura as I did, I had met many of them .... For example, two dose friends of [Admiral] Yamamoto Isoroku [1884-1943] told me the following story: After the great victory Yamamoto achieved in the air attack on Pearl Harbor, he had a meeting with [General] Tojo Hideki. Yamamoto told him that this was no longer the era of battleships with their big guns. Rather, it was unquestionably the era of the airplane. Therefore every effort should be made to build more airplanes. Yamamoto was right, of course, in having said this.

Tojo, however, being the kind of person he was, in addition to being an army general, was consumed with jealousy, for, unlike the navy, the army had yet to achieve any major victories. The result was that, due to his stubbornness, Tojo told Yamamoto that he refused to accept orders from him because the latter was merely the commander-in-chief of the combined fleet while he [Tojo) was the nation's prime minister. They were like two children fighting. Yamamoto's two friends claimed that because Japan wasn't building more airplanes, it was losing the war.

[Sogen) said to them, "Why wasn't Yamamoto willing to risk his position in opposing him? Why didn't he tell Tojo he would resign his position as combined fleet commander?" ... If I had been there, I would have let go with an explosive "Fool!" ... The army and the navy don't exist for themselves, they exist to defend the country .... With people like these at the top how can they accomplish what is expected of them? We're already losing. With people like them as commanders, we cannot expect to win .... They're only thinking about themselves.32

Even though Sogen claimed to have realized that Japan faced defeat at an early stage of the war with the Allies, he did not withdraw his support for the nation's war effort. On the contrary, he wrote that on numerous occasions he had given lectures and led "training camps" (rensei kai) to help maintain the people's morale. One of his earliest efforts (omitted from his book) was given on national radio (NHK) in July 1939. Speaking in support of the government's newly issued order for a general mobilization of the civilian population, he said:

Lieutenant Colonel Sugimoto Goro was revered as a god of war, having undergone Zen training .... Had he possessed a weak spirit, or lacked the ability to carry out [what needed to be done), he would have been held in contempt by the people, given today's emergency situation. Let us be inspired by the [Zen] expression: ''A day without work is a day without eating." If we were to carry this over into every aspect of our daily lives, that is to say, if we were to dedicate ourselves totally to repaying the debt of gratitude we owe the nation, we would have a splendidly coherent life. Though we found ourselves on the home front and not on the battlefield, we would have nothing to be ashamed of.33

A second lecture, which Sogen did choose to write about, was given at the Naval Technical Research Institute in Tokyo. With evident pride, he twice mentioned that all the members of this institute were university graduates and that it was the most important center for naval technology in Japan. His lecture was given to all two hundred workers at the institute and lasted for a full three hours and twenty minutes. Perhaps embarrassed by its content (within the context of the postwar era), he did not give the details of his talk, but he claimed there was not so much as a cough from his audience the entire time. "I'll be satisfied if what I've said has been of even a small benefit to the state." he concluded.34 As an example of one of the training camps he led, Sogen described a military-sponsored visit of some forty-four wounded war veterans to Engakuji. They underwent Zen training as best they could for a one-week period. When it came time for them to leave, Sogen addressed them:

Even though you have sustained injuries to your eyes or to your hands, you are still brave and seasoned warriors. This is now a time when the people must give everything they have to the state. You, too, have something precious to give. That is to say, transfer your spirit to the people of this nation, hardening their resolve. You were not sent to a place like this to be pampered. I took charge of you because I wanted you to have the resolve and the courage to offer up the last thing you possess [to the state].35

"They cried." Sogen reported, "all of them."36

Sogen was not critical of all those in leadership positions during the war. There was one institution, or figure, for whom he had unwavering respect both during and after the war, the emperor: "The debt of gratitude owed the emperor ... is so precious that there is no way to express one's gratitude for it or to repay it."37 Although Sogen didn't discuss Emperor Hirohito's wartime role, he had nothing but praise for his actions following Japan's defeat. It was the emperor's "nobility of spirit." Sogen maintained, that so moved General Douglas MacArthur, head of the Allied Occupation Forces, that he decided to treat Japan leniently, maintaining its integrity as a single country. It was in this spirit that Sogen left his Japanese readers with the following parting thought: "The prosperity and everything we enjoy today is completely due to the selflessness and no-mindedness of the emperor's benevolence. I want you to remember this. Human beings must never forget the debt of gratitude they owe [others )."38 Though the terms "imperial-state Zen" and "soldier Zen" may have ceased being rallying cries in postwar Japan, Sogen, like Yamada Mumon, demonstrates that their spirit lived on. He was far from the only postwar Zen master to maintain this attitude, a fact which explains, at least in part, why even today not a single branch of the Rinzai Zen sect has ever publicly discussed, let alone apologized for, its wartime role. To do so would call into question not only the modern history of that sect but much of its seven-hundred-year history in Japan.

Ichikawa Hakugen While the Rinzai Zen sect has spawned some of the strongest advocates of imperial-state Zen and soldier Zen, it has also produced some of its most severe critics. Yanagida Seizan may be considered one, though his was at best a limited critique. The Rinzai Zen-affiliated priest and scholar Ichikawa Hakugen took up this challenge on a much broader scope and a much deeper level.

Hakugen's classic statement on the role of Buddhism, particularly Zen, in the wartime era is The War Responsibility of Buddhists (Bukkyosha no Senso Sekinin), published in 1970. Three years before, in 1967, he had begun to examine this issue in Zen and Contemporary Thought (Zen to Gendai Shiso). He developed his ideas still further in a series of articles and books including Religion Under Japanese Fascism (Nihon Fashizumu Ka no Shukyo), published in 1975, and a major article entitled "The Ideology of the Military State" (Kokubo Kokka Shiso) included in Buddhism During the War(Senji Ka no Bukkyo), published in 1977 and edited by Nakano Kyotoku.

In Religion Under Japanese Fascism, Hakugen justified his call for a critical evaluation of the relationship between Buddhism and Japanese militarism:

In recent times, Japanese Buddhists talk about Buddhism possessing the wisdom and philosophy to save the world and humanity from collapse. However, I believe Buddhism first has to reflect on what, if any, doctrines and missionary work it advocated during the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods to oppose exploitation and oppression within Japan itself, as well as Korea, Taiwan, Okinawa, China, and Southeast Asia. Beyond that, Buddhism has the duty and responsibility to clarify individual responsibility for what happened and express its determination [never to let it happen again].39

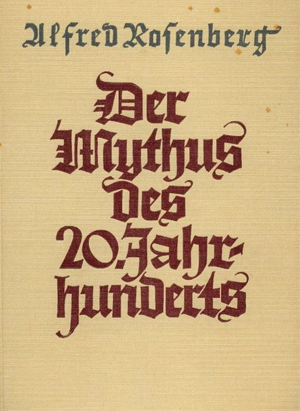

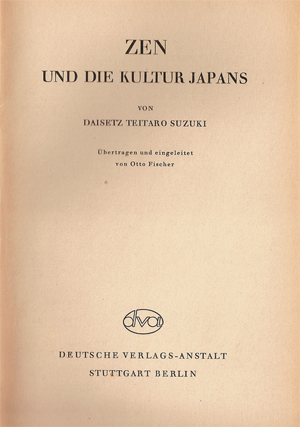

In the preceding work, as well as many of his other works, Hakugen set out to do just what he said needed to be done. He not only clarified individual responsibility but also looked at those doctrinal and historical aspects of both Zen and Buddhism which he believed lent themselves, rightly or wrongly, to abuse by supporters of Japanese militarism. One of the individuals whom Hakugen felt was most responsible for the development of imperial-way Zen was D. T. Suzuki.

Hakugen felt that Suzuki's position as expressed in A Treatise on the New [Meaning of] Religion in the latter part of the Meiji period helped form the theoretical basis for what followed. In justification of this assertion, he quoted the same passage from that treatise introduced in chapter 2. He stated that Suzuki had been speaking of China when he mentioned a "lawless country" in this treatise. Hakugen then went on to say:

[Suzuki] considered the Sino-Japanese War to be religious practice designed to punish China in order to advance humanity. This is, at least in its format, the very same logic used to support the fifteen years of warfare devoted to "The Holy War for the Construction of a New Order in East Asia." Suzuki didn't stop to consider that the war to punish China had not started with a Chinese attack on Japanese soil, but, instead, took place on the continent of China. Suzuki was unable to see the war from the viewpoint of the Chinese people, whose lives and natural environment were being devastated. Lacking this reflection, he considered the war of aggression on the continent as religious practice, as justifiable in the name of religion ....

The logic that Suzuki used to support his "religious conduct" was that of "the sword that kills is identical with the sword that gives life" and "kill one in order that many may live." It was the experience of "holy war" that spread this logic throughout all of Asia. It was Buddhists and Buddhist organizations that integrated this experience of war with the experience of the emperor system.40

Needless to say, Suzuki was not the only Zen adherent who Hakugen believed shared responsibility for the war. Mention has already been made, for example, of Harada Daiun Sogaku, whom Hakugen identified as a "fanatical militarist." Hakugen went on to point out that yet another of Harada's chief disciples and Dharma successors, Yasutani Hakuun (1885-1973) was, in postwar years, "no less a fanatical militarist and anticommunist" than his master.41

Specifically, in 1951, Hakuun established a publication known as Awakening Gong (Gyosho) as a vehicle for his religious and political views. The following passage is typical of his political views:

Those organizations which are labeled right-wing at present are the true Japanese nationalists. Their goal is the preservation of the true character of Japan. There are, on the other hand, some malcontents who ignore the imperial household, despise tradition, forget the national polity, forget the true character of Japan, and get caught up in the schemes and enticements of Red China and the Soviets. It is resentment against such malcontents that on occasion leads to the actions of young [assassin) Yamaguchi Ojiya or the speech and behavior of [right-wing novelist) Mishima Yukio.42

Coupled with Hakuun's admiration for Japan's right wing was his equal distaste for Japan's labor movement and institutions of higher learning. Less than a year after the above, he wrote:

It goes without saying the leaders of the Japan Teachers' Union are at the forefront of the feeble-minded [in this country) .... They, together with the four opposition political parties, the General Council of Trade Unions, the Government and Public Workers Union, the Association of Young Jurists, the Citizen's League for Peace in Vietnam, and so forth, have taken it upon themselves to become traitors to the nation ....

The universities we presently have must be smashed one and all. If that can't be done under the present constitution, then it should be declared null and void just as soon as possible, for it is an un-Japanese constitution ruining the nation, a sham constitution born as the bastard child of the allied occupation forces.43

As for the theoretical basis of Hakuun's political views, he shared the following with his readers six months later: "All machines are assembled with screws having right-hand threads. Right-handedness signifies coming into existence, while left-handedness signifies destruction."44 When Hakuun went to the United States to lead meditation training on seven different occasions between 1962 and 1969, sentiments like the above were noticeably missing from his public presentations. It would appear that they were for domestic consumption only. Yet Hakuun did not hesitate to tell his American students what the true cause of conflict in the world was. In a 1969 essay entitled "The Crisis in Human Affairs and the Liberation Found in Buddhism," he wrote:

Western-style social sciences have been based on a deluded misconception of the self, and they attempt to develop this "I" consciousness. This is dichotomy. As a result, they have reinforced the idea of dichotomy between human beings which has lead to conflicts and fighting. They have even created a crisis which may destroy all of mankind.45

Naturally, Hakugen was sharply critical of "god of war" Sugimoto Goro and his Zen master and eulogist Yamazaki Ekiju:

First, Sugimoto and Yamazaki used Zen as nothing more than a means for the practice of the imperial way. Not only that, but by forcing the meaning and tenets of Zen to fit within the context of a religion centered on the emperor, Zen itself was obliterated.46

Hakugen also pointed out that the Soto Zen sect had gone so far as to actually change its fundamental principles in order to place itself squarely behind the state's war efforts. In 1940 this sect revised its creed to read: "The purpose of this sect is ... to exalt the great principle of protecting the state and promoting the emperor, thereby providing a blessing for the eternal nature of the imperial throne while praying for the tranquility of a world ruled by his majesty."47 In its new creed promulgated following Japan's defeat, the Soto sect dropped the preceding paragraph in its entirety, as it was clearly no longer politically acceptable.

Hakugen was the first postwar Zen and Buddhist scholar to try to determine what Buddhist doctrines or pre-Meiji historical developments might have either contributed to or facilitated Buddhist war collaboration. He identifies one example of a contributing historical development in Zen and Contemporary Thought:

In the Edo period [1600-1867) Zen priests such as Bunan [1603-76), Hakuin [1685-1768), and Torei [1721-92) attempted to promote the unity of Zen and Shinto by emphasizing Shinto's Zen-like features. While this resulted in the further assimilation of Zen into Japan, it occurred at the same time as the establishment of the power of the emperor system. Ultimately this meant that Zen lost almost all of its independence, the impact of the High Treason Incident on the Zen world representing the final stage of this transformation.48

Hakugen also looked for those Buddhist tenets that seem to· have made Buddhism susceptible to militaristic manipulation. One example he gave of such an idea concerned the Buddhist teaching of wago (harmony). Out of harmony, he postulated, had come Buddhism's "nonresistance" and "tolerance":

With what has modern Japanese Buddhism harmonized itself? With State Shinto. With the power of the state. With militarism. And therefore, with war. To what has modern Japanese Buddhism been nonresistant? To State Shinto. To the power of the state. To militarism. To wars of aggression. Toward what has modern Japanese Buddhism been tolerant? Toward the above mentioned entities with which it harmonized. Therefore, toward its own war responsibility.

And I should not forget to include myself as one of those modern Japanese Buddhists who did these things.49

Hakugen's self-indictment was, in fact, quite appropriate, for during the war years he had indeed been a strong advocate of Japan's "holy war." For example, in September 1942, he published an article in Daihorin entitled, "War, Science, and Zen." He began his article with the following observation:

Pacifistic humanitarianism, which takes the position that all conflicts are inhumane crimes, is the sentiment of moralists who don't know the true nature of life. We, on the other hand, know of numerous instances in which peace is far more unwholesome and evil than conflict. In this regard, Nietzsche, who taught the logic of war instead of peace, was a man with a firm grip on living truth rather than the abstractions of pacificists.50