Dearborn, Michiganby Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/26/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- The International Jew, by Henry Ford

-- Did the Jews Foresee the World War?, by Henry Ford

-- 100 Years Later, Dearborn Confronts The Hate Of Hometown Hero Henry Ford, by Bill McGraw

-- [Henry] Ford and the Fuhrer, by Ken Silverstein

-- Individual Isolationists: Henry Ford, by Historical Boys' Clothing

-- Power, Ignorance, and Anti-Semitism: Henry Ford and His War on Jews, by Jonathan R. Logsdon

-- Facts and Fascism, by George Seldes

-- The Russian Roots of Nazism: White Emigres and the Making of National Socialism, 1917-1945, by Michael Kellogg

-- Orville Hubbard -- the ghost who still haunts Dearborn, by David L. Good

-- Dearborn, Michigan, by Wikipedia

Dearborn, Michigan

City of Dearborn

Ford Motor Company World Headquarters

Ford Motor Company World HeadquartersMotto(s): "Home Town of Henry Ford"[1]

Country United States

State Michigan

County Wayne

Settled 1786

Incorporated 1893 (village)

1927 (city)

Government

• Type Strong mayor–council

• Mayor John B. O'Reilly Jr.

Area[2]

• City 24.52 sq mi (63.50 km2)

• Land 24.23 sq mi (62.77 km2)

• Water 0.28 sq mi (0.73 km2)

Elevation 591 ft (180 m)

Population (2010)[3]

• City 98,153

• Estimate (2018)[4] 94,333

• Density 3,899.11/sq mi (1,505.44/km2)

• Metro 4,285,832 (Metro Detroit)

Time zone UTC−5 (EST)

• Summer (DST) UTC−4 (EDT)

ZIP code(s)

48120, 48121, 48123, 48124, 48126, 48128

Area code(s) 313

FIPS code 26-21000

GNIS feature ID 0624432[5]

Website Official website

Dearborn is a city in the State of Michigan. It is located in Wayne County and is part of the Detroit metropolitan area. Dearborn is the eighth largest city in the State of Michigan. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 98,153 and is home to the largest Muslim population in the United States.[6] First settled in the late 18th century by ethnic French farmers in a series of ribbon farms along the Rouge River and the Sauk Trail, the community grew in the 19th century with the establishment of the Detroit Arsenal on the Chicago Road linking Detroit and Chicago. In the 20th century, it developed as a major manufacturing hub for the automotive industry.

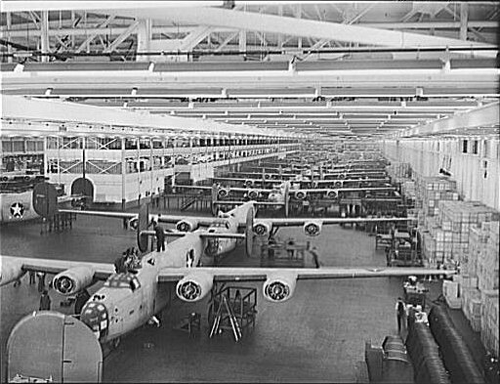

Henry Ford was born on a farm here and later established an estate in Dearborn, as well as his River Rouge Complex, the largest factory of his Ford empire. He developed mass production of automobiles, and based the world headquarters of the Ford Motor Company here. The city has a campus of the University of Michigan as well as Henry Ford College. The Henry Ford, the United States' largest indoor-outdoor historic museum complex and Metro Detroit's leading tourist attraction, is located here.[7][8]

Dearborn residents are Americans primarily of European or Middle Eastern ancestry, many descendants of 19th and 20th-century immigrants. Because of new waves of immigration from the Middle East in the late 20th century, the largest ethnic grouping is now composed of descendants of various nationalities of that area: Christians from Lebanon and Palestine, as well as Muslim immigrants from Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. The primary European ethnicities, as identified by respondents to the census, are German, Polish, Irish, and Italian.

HistoryBefore European encounter, the area had been inhabited for thousands of years by successive indigenous peoples. Historical tribes belonged mostly to the Algonquian-language family, especially the Council of Three Fires, the Potawatomi and related peoples. In contrast, the Huron (Wyandot) were Iroquoian speaking. French colonists had a trading post at Fort Detroit and a settlement developed there in the colonial period. Another developed on the south side of the Detroit River in what is now southwestern Ontario, near a Huron mission village. French and French-Canadian colonists also established farms at Dearborn in this period. France ceded all of its territory east of the Mississippi River in North America to Great Britain in 1763 after losing to the English in the Seven Years' War.

Beginning in 1786, after the United States gained independence in the American Revolutionary War, more European Americans entered this region, settling in Detroit and the Dearborn area.[9] With population growth, Dearborn Township was formed in 1833 and the village of Dearbornville in 1836, each named after patriot Henry Dearborn, a general in the American Revolution who later served as Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson. The Town of Dearborn was incorporated in 1893. Through much of the 19th century, the area was largely rural and dependent on agriculture.

Stimulated by industrial development in Detroit and within its own limits, in 1927 Dearborn was established as a city. Its current borders result from a 1928 consolidation vote that merged Dearborn and neighboring Fordson (previously known as Springwells), which feared being absorbed into expanding Detroit.

According to historian James W. Loewen, in his book Sundown Towns (2005), Dearborn discouraged African Americans from settling in the city. In the early 20th century, both whites and Afrian Americans migrated to Detroit for industrial jobs. Over time, some city residents relocated in the suburbs. Many of Dearborn's residents "took pride in the saying, 'The sun never set on a Negro in Dearborn'". According to Orville Hubbard, the segregationist mayor of Dearborn from 1942 to 1978, "as far as he was concerned, it was against the law for a Negro to live in his suburb."[10]

The area between Dearborn and Fordson was undeveloped, and still remains so in part. Once farm land, much of this property was bought by Henry Ford for his estate, Fair Lane, and for the Ford Motor Company World Headquarters. Later developments in this corridor were the Ford airport (later converted to the Dearborn Proving Grounds), and other Ford administrative and development facilities.

More recent additions are The Henry Ford (a reconstructed historic village and museum), the Henry Ford Centennial Library, the super-regional shopping mall Fairlane Town Center, and the Ford Performing Arts Center. The open land is planted with sunflowers and often with Ford's favorite crop of soybeans. The crops are never harvested.

With the growth and achievements of the Arab-American community, they developed and in 2005 opened the Arab American National Museum (AANM), the first museum in the world devoted to Arab-American history and culture. Arab Americans in Dearborn include descendants of Lebanese Christians who immigrated in the early twentieth century to work in the auto industry, as well as more recent Arab immigrants and their descendants from other, primarily Muslim nations.[11]

In January 2019, Dearborn Mayor John "Jack" O'Reilly, Jr., terminated the contract of Bill McGraw, new editor of the Dearborn Historian, a city publication. He refused to allow distribution of the Autumn 2018 issue to subscribers. That issue, on the 100th anniversary of Henry Ford's acquisition of the Dearborn Independent newspaper, discussed the influence that Ford exerted in expressing his anti-Semitism. The mayor's suppression of the issue received national publicity.[12][13] The Dearborn Historical Commission held an emergency meeting and passed a resolution calling for the mayor to reverse these actions.[14] The suppressed article was published in DeadlineDetroit and may be read here.

Geography Parklane Towers

Parklane TowersAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 24.5 square miles (63 km2), of which 24.4 square miles (63 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (0.37%) is water. The city developed on both sides of the Rouge River. An artificial waterfall/low head dam was constructed by Henry Ford on his estate to power its powerhouse. The Upper, Middle, and Lower Branches of the river come together in Dearborn. The river is widened and channeled near the Rouge Plant to allow lake freighter access.

Fordson Island (42°17′38″N 83°08′52″W) is an 8.4 acres (3.4 hectares) island about three miles (5 km) upriver on the River Rouge from its confluence with the Detroit River. Fordson Island is the only major island in a tributary to the Detroit River. The island was created in 1922 when engineers dug a secondary trench to reroute the River Rouge to increase navigability for shipping purposes; businesses needed it to be navigable by the large lake freighters. The island is privately owned, and public access is prohibited. The island is part of the city of Dearborn, which has no frontage along the Detroit River.[15][16]

Dearborn is among a small number of municipalities that own property in other cities. It owns the 626-acre (2.53 km2) Camp Dearborn in Milford, Michigan, which is located 35 miles (56 km) from Dearborn.[17] Dearborn was among an even smaller number of cities that hold property in another state: for a time the city owned the "Dearborn Towers" apartment complex in Clearwater, Florida, but this has been sold. Camp Dearborn is considered part of the city of Dearborn. Revenues generated by camp admissions are incorporated into the city's budget.

DemographicsAs of the 2010 census, the population of Dearborn was 98,153. The racial and ethnic composition was 89.1% Whites, 4.0% black or African-American, 0.2% Native American, 1.7% Asian, 0.2% Non-Hispanics of some other race, 4.0% reporting two or more races and 3.4% Hispanic or Latino.[22] 41.7% were of Arab ancestry (categorized as "White" in Census collection data).[23]

Dearborn has a large community of descendants of ethnic Europeans who arrived as immigrants from the mid-19th into the 20th centuries. Their ancestors generally first settled in Detroit: Irish, German, Italians, and Polish. It is also a center of Maltese American settlement, from the Mediterranean island of Malta. Also attracted to jobs in the auto industry, some were among immigrant Maltese who first settled in Corktown.[24]

The city has a small African American population, many of whose ancestors came to the area from the rural South during the Great Migration of the early twentieth century.[25]

In Census 2000, 61.9% spoke only English, while 29.3% spoke Arabic, 1.9% Spanish, and 1.5% Polish as first languages. There were 36,770 households out of which 31.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.0% were married couples living together, 9.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.1% were non-families. 30.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.65 and the average family size was 3.42.

In the city, the population was spread out with 27.8% under the age of 18, 8.3% from 18 to 24, 29.2% from 25 to 44, 19.1% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $44,560, and the median income for a family was $53,060. Males had a median income of $45,114 versus $33,872 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,488. About 12.2% of families and 16.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.4% of those under age 18 and 7.6% of those age 65 and over.

As of the 2012 estimate, Dearborn's population was thought to have fallen to 96,474, a decrease of 1.7% since 2010. Over the same period, though, SEMCOG, the local statistics agency of Metro Detroit Council of Governments, has estimated the city to have grown to 99,001, or an increase of 1.2% since 2000. SEMCOG's July 2014 estimate listed Dearborn with a population of 102,566.[26]

Arab Americans The Arab American National Museum in Dearborn

The Arab American National Museum in DearbornMain article: History of the Middle Eastern people in Metro Detroit

The city's population includes 40,000 Arab Americans. Since the late 20th century, there has been growth in immigration from new areas of the Middle East, such as Syria.[27] Arab Americans own many shops and businesses, offering services in both English and Arabic.[28]

Per the 2000 census, Arab Americans totaled 29,181 or 29.85% of Dearborn's population; many are descendants of families who have been in the city since the early 20th century. The city has the largest proportion of Arab Americans in the United States.[29] As of 2006 Dearborn has the largest Lebanese American population in the United States.[30]

The first Arab immigrants came in the early-to-mid-20th century to work in the automotive industry and were chiefly Lebanese Christians (Maronites). Other immigrants from the Mideast (Assyrians/Chaldeans/Syriacs) have also immigrated to the area. Since then, Arab immigrants from Yemen, Iraq and Palestine, most of whom are Muslim, have joined them. Lebanese Americans comprise the largest group of ethnic Arabs.[31][32] The Arab Muslim community has built the Islamic Center of America, the largest mosque in North America,[33] and the Dearborn Mosque. More Iraqi refugees have come, fleeing the continued war in their country since 2003.

Warren Avenue has become the commercial center of the Arab-American community. The Arab American National Museum is located in Dearborn.[34] The museum was opened in January 2005 to celebrate the Arab American community's history, culture and contributions to the United States.

EconomyFurther information: Economy of metropolitan Detroit

Dearborn skyline with Ford River Rouge Complex in background, 1973

Dearborn skyline with Ford River Rouge Complex in background, 1973 Edward Hotel and conference center

Edward Hotel and conference centerFord Motor Company has its world headquarters in Dearborn.[35] In addition its Dearborn campus contains many research, testing, finance, and some production facilities. Ford Land controls the numerous properties owned by Ford, including sales and leasing to unrelated businesses, such as the Fairlane Town Center shopping mall. DFCU Financial, the largest credit union in Michigan, was created for Ford and related companies' employees.

One of the largest employers in Dearborn is Oakwood Healthcare System. Other major employers include auto suppliers like Visteon, education facilities such as Henry Ford Community College, and museums such as The Henry Ford. Other businesses headquartered in Dearborn include Carhartt (clothing), Eppinger (fishing lures), AAA Michigan (insurance), and the Society of Manufacturing Engineers.

Largest employersAccording to the City's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[36] the largest employers in the city are:

# / Employer / # of employees

1 / Ford / 44,000

2 / ADP / 10,000

3 / Automotive Components Holdings (Ford/Visteon) / 7,000

4 / Oakwood Health System / 6,167

5 / Severstal (now AK Steel) / 4,900

6 / Percepta / 4,450

7 / Dearborn Board of Education / 3,339

8 / Auto Club of Michigan / 1,752

9 / EP Management Corporation / 1,400

10 / United Technologies Auto (Lear) / 1,200

Education

Colleges and universities University of Michigan–Dearborn

University of Michigan–DearbornUniversity of Michigan–Dearborn and Henry Ford College are located in Dearborn on Evergreen Road and are adjacent to each other. Concordia University Dearborn Center, and Central Michigan University both offer classes in Dearborn.[37][38] Career training schools include Kaplan Career Institute, ITT Tech, and Sanford Brown College.

Primary and secondary schoolsDearborn residents, along with a small portion of Dearborn Heights residents, attend Dearborn Public Schools.[39] The system operates 34 schools including three major high schools: Fordson High School, Dearborn High School and Edsel Ford High School. The public schools serve more than 18,000 students in the fourth-largest district in the state.

Divine Child High School and Elementary School are in Dearborn as well; the high-school is the largest private coed high school in the area. Henry Ford Academy is a charter high school inside Greenfield Village and the Henry Ford Museum. Another charter secondary school is Advanced Technology Academy. Dearborn Schools operated the Clara B. Ford High School inside Vista Maria, a non-profit residential treatment agency for girls in Dearborn Heights. Clara B. Ford High School became a charter school in the 2007–08 school year.

A small portion of the city limits is within the Westwood Community School District.[40] The sections of Dearborn within the district are zoned for industrial and commercial uses.[41]

The Islamic Center of America operates the Muslim American Youth Academy (MAYA), an Islamic elementary and middle school.[42]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit operates Sacred Heart Elementary School. It previously operated the St. Alphonsus School in Dearborn. In 2003 the archdiocese closed the high school of St. Alphonsus;[43] and in 2005 closed the St. Alphonsus elementary school.[44]

Global Educational Excellence operates multiple charter schools in Dearborn: Riverside Academy Early Childhood Center, Riverside Academy East Campus (K-5), and Riverside Academy West Campus (6–12).[45]

Public libraries Henry Ford Centennial Library

Henry Ford Centennial LibraryDearborn Public Library includes the Henry Ford Centennial Library, which is the main library; and the Bryant and Esper branches.[46]

Dearborn's first public library opened in 1924 at the building now known as the Bryant Branch. This served as the main library until the Ford library opened in 1969. In 1970 what became known as the Mason building was classified as a branch library. The library was renamed in 1977 after Katharine Wright Bryant, who developed a plan for the library and campaigned for it.[47]

Around April 1963 the Ford Motor Company granted the City of Dearborn $3,000,000 to build a library as a memorial to Henry Ford. Ford Motor Company deeded 15.3 acres (6.2 ha) of vacant land for the public library to the city on July 30, 1963, the centennial or 100th anniversary of Henry Ford's birth. The Ford Foundation later granted the library an additional $500,000 for supplies and equipment. On November 25, 1969 the library was dedicated. Library employees have occupied the building since its opening; originally only the library had offices in the building. In 1979 the library staff gave up the western side's meeting rooms, and the City of Dearborn Health Department occupied those rooms.[48]

The Esper Branch, the smallest branch, is located in what is known as the Arab residential quarter of the city. The library has about 35,000 books, entertainment and educational videocassettes, music CDs, children's music cassettes, audio books, and magazines. Newspapers are also available. It features many Arabic-language books, newspapers, and videocassettes for Arabic-speaking residents. This library was dedicated on October 12, 1953. Originally named the Warren Branch, this structure had replaced the Northeast Branch, which opened in a storefront in 1944. In October 1961 it was named after city councilman Anthony M. Esper.[49]

Post officeDuring the years 1934 to 1943, during and after the Great Depression, murals were commissioned for federal public buildings in the United States through the Section of Painting and Sculpture, later called the Section of Fine Arts, of the Treasury Department. They often featured representation of local history. In 1938 artist Rainey Bennett painted an oil-on-canvas mural for the federal post offices in Dearborn titled, Ten Eyck's Tavern on Chicago Road.

InfrastructureSports facilitiesSports facilities include the Dearborn Ice Skating Center.

TransportationFurther information: Transportation in metropolitan Detroit and Dearborn (Amtrak station)

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Dearborn, operating its Wolverine three times daily in each direction between [[Chicago, Illinois and Pontiac, Michigan, via Detroit. Baggage cannot be checked at this location; however, up to two suitcases, in addition to any "personal items" such as briefcases, purses, laptop bags, and infant equipment, are allowed on board as carry-ons. There are two rail stops in Dearborn: the regular Amtrak station and a rarely used station at Greenfield Village. Amtrak operates on Norfolk Southern's (NS) "Michigan Line". This track runs from Dearborn to Kalamazoo, Michigan. Most of the freight traffic on these rails is related to the automotive industry. Norfolk Southern's Dearborn Division offices are also located in Dearborn.

Dearborn is served by buses of both the Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) systems.

From 1924 to 1947, Dearborn was the site of Ford Airport. It featured the world's first concrete runway and the first scheduled U.S. passenger service.[citation needed]

GovernmentDearborn has a mayor-council form of government. As of 2019, the Mayor of the City of Dearborn is John B. "Jack" O'Reilly, Jr.[50] The City Council President is Susan Dabaja.[51]

MediaThe metropolitan-area newspapers are The Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press.

The Dearborn & Dearborn Heights Press and Guide publishes local news for Dearborn and the neighboring Dearborn Heights.[52] The Arab American News is published in Dearborn.[53]

Notable people Henry Ford's Fair Lane estate in Dearborn

Henry Ford's Fair Lane estate in Dearborn River Rouge from Henry Ford's estate

River Rouge from Henry Ford's estate• Frankie Andreu - professional cyclist, rode Tour De France multiple years

• Bazzi - singer

• Dave Brandon – CEO of Toys "R" Us, chairman of Domino's Pizza

• David Burtka – chef and actor, married to Neil Patrick Harris

• Brian Calley – 63rd Lieutenant Governor of Michigan

• Garrett Clayton – actor

• Jim Cummins – NHL player

• John Dingell – former dean of the U.S. House of Representatives, longest-serving Congressman

• Agnes Dobronski – Michigan educator and legislator

• Ronnie Duman - auto racer

• Chad Everett – actor, Medical Center, The Last Challenge, Made in Paris, Airplane II: The Sequel

• Rima Fakih – Miss Michigan USA 2010, Miss USA 2010,[54]

• Henry Ford – iconic automaker, founder of Ford Motor Company

• Edsel Ford – Henry Ford's son, second president of Ford Motor and co-namesake of Fordson

• Dan Gheesling – winner of Big Brother 10 (U.S.) and runner-up on Big Brother 14 (U.S.)

• Russ Gibb - concert promoter and media figure

• George Z. Hart – Michigan state senator

• Ahmad Harajly – rugby player (USA Rugby)

• Orville L. Hubbard – Mayor of Dearborn from 1942 to 1978

• Al Iafrate – NHL defenseman

• Art James – TV quiz-show host

• John C. Kornblum – diplomat, former Ambassador to Germany

• Derek Lowe – Major League Baseball pitcher, 2004 World Series champion with Boston Red Sox

• Don Matheson – actor, Land of the Giants

• Nancy Milford – author and biographer

• Alan Mulally – CEO of Ford Motor Company

• Dorothy Naum - baseball player

• Johnny Pacar – actor, Flight 29 Down, Make It or Break It, Now You See It...

• Eugenia Paul – actress and dancer

• George Peppard – film actor, known for Breakfast at Tiffany's, How the West Was Won, and more

• Tom Price - United States Secretary of Health and Human Services

• Brian Rafalski – NHL defenseman (New Jersey Devils, Detroit Red Wings)

• Doug Ross – college ice hockey coach

• Soony Saad – soccer player

• Scott Sanderson – All-Star Major League Baseball pitcher in 19 Major League seasons for seven teams

• Norbert Schemansky – four-time Olympic medalist in weightlifting

• Suzanne Sena – host of Independent Film Channel program Onion News Network and former Fox News anchor

• Serena Shim – Lebanese-American journalist

• Jim Snyder - Major League Baseball player and manager

• Edward Stinson – aviation pioneer

• Windy & Carl – musicians

Target of Christian missionaries and politiciansIn the 21st century, the Arab-American community in Dearborn has sometimes been subject to public prosyletizing by Protestant Christian missionaries and inflammatory statements by political candidates. In 2010, Nabeel Qureshi, David Wood, and two other people acting as Christian missionaries, were arrested at the Dearborn International Arab Festival. They had been handing out Christian literature aimed at Muslim believers. The four were prosecuted for breach of the peace. Police ordered them to stop filming the incident, to provide identification, and to move at least five blocks from the border of the fair.[55]

After reviewing the video evidence, the jury acquitted the defendants.[56] The four defendants filed a separate civil suit against the city. Dearborn was found to have violated their constitutional rights related to freedom of speech. The city settled the lawsuit and issued a formal apology to the individuals.[57]

Sharron Angle, a Republican senatorial candidate in Nevada, said in an October 2010 political speech that the Arab Americans in Dearborn contributed to a "militant terrorist situation,"[58][59] and that the city government was enforcing Islamic sharia law.[58] Mayor Jack O'Reilly strongly criticized Angle for her deliberate misrepresentation of the city and its residents, and he called her comments "shameful."[58] He said her claim was based on distorted Tea Party accounts of the arrest of members of an anti-Islam group at an Arab festival.[58]

Preacher Terry Jones of Gainesville, Florida, known for burning a Quran, the sacred book of Islam, planned a protest in 2011 outside the Islamic Center of America. Local authorities required him either to post a $45,000 "peace bond" to cover Dearborn's cost if Jones incited violence, or to go to trial. Jones contested that requirement, and he and his co-pastor Wayne Sapp refused to post the bond. They were held briefly in jail, while claiming violation of First Amendment rights. That night Jones was released by the court.[60] The ACLU had filed an amicus brief in support of Jones's protest plans.[61] A week later, on April 29, Jones led a rally at the Dearborn City Hall, in a designated free speech zone. Riot police were called out to control counter protesters.[62][63][64] Jones also planned to speak at the annual Arab Festival on June 18, 2011, but his route was blocked by protesters, six of whom were arrested. Police said they did not have enough officers present to maintain safety.[65] Christian missionaries accompanied Jones with their own protest signs. Both festivalgoers and counter protesters said the missionaries had yelled insults at Arabs, Muslims, and Catholics.[66]

On November 11, 2011, Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Robert Ziolkowski vacated the "breach of peace" ruling against Jones and Sapp on the grounds that they were denied due process.[67] On April 7, 2012 Jones led another protest in front of the Islamic Center of America, where he spoke about Islam and free speech. The mosque officials had locked it down to prevent damage. The city used thirty police cars to block traffic from the area in an effort to prevent a counter protest.[68]

Historical timeline

European exploration and colonization• 1603 – French lay claim to unidentified territory in this region, naming it New France.

• July 24, 1701 – Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac and his soldiers first land at what is now Detroit.

• November 29, 1760 – The British take control of the area from France.

• 1780 – Pierre Dumais clears farm near what is today's Morningside Street in Dearborn's South End.

Early U.S. history• 1783 – By terms of the Treaty of Paris ending the American Revolutionary War, Great Britain cedes territory south of the Great Lakes to the United States, although the British retain practical control of the Detroit area and several other settlements until 1797.

• 1786 – Agreed year of first permanent settler in present-day Dearborn.

• 1787 – Territory of the US north and west of the Ohio River is officially proclaimed the Northwest Territory.

• December 26, 1791 – Detroit environs become part of Kent County, Ontario.

• 1795 – James Cissne becomes first settler in what is now west Dearborn.

• 1796 – Wayne County is formed by proclamation of the acting governor of the Northwest Territory. Its original area is 2,000,000 square miles (5,200,000 km2), stretching from Cleveland, Ohio, to Chicago, Illinois, and northwest to Canada.

• May 7, 1800 – Indiana Territory, created out of part of Northwest Territory, although the eastern half of Michigan including the Dearborn area, was not attached to Indiana Territory until Ohio was admitted as a state in 1803.

• January 11, 1805 – Michigan Territory officially created out of a part of the Indiana Territory.

• June 11, 1805 – Fire destroys most of Detroit.

• November 15, 1815 – Current boundaries of Wayne County drawn, county split into 18 townships.

• January 5, 1818 – Springwells Township established by Gov. Lewis Cass.

• October 23, 1824 – Bucklin Township created by Gov. Lewis Cass. The area ran from Greenfield to approximately Haggerty and from Van Born to Eight Mile.

• 1826 – Conrad Ten Eyck builds Ten Eyck Tavern at Michigan Avenue and Rouge River.

• 1827 – Wayne County's boundaries changed to its current 615 square miles (1,593 km2).

• April 12, 1827 – Springwells and Bucklin townships formally organized and laid out by gubernatorial act.

• October 29, 1829 – Bucklin Township split along what is today Inkster Road into Nankin (west half) and Pekin (east half) townships.

• March 21, 1833 – Pekin Township renamed Redford Township.

• March 31, 1833 – Greenfield Township created from north and west sections of Springwells Township, including what is now today east Dearborn.

• April 1, 1833 – Dearborn Township created from southern half of Redford Township south of Bonaparte Avenue (Joy Road).

• 1833 – Detroit Arsenal built.

• October 23, 1834 – Dearborn Township renamed Bucklin Township.

• March 26, 1836 – Bucklin Township renamed Dearborn Township.

• January 26, 1837 – Michigan admitted to the Union as the 26th state. Stevens T. Mason is first governor.

• 1837 – Michigan Central Railroad extended through Springwells Township. Hamlet of Springwells rises along railroad.

• April 5, 1838 – Village of Dearbornville incorporates. Village later unincorporated on May 11, 1846.

• 1849 Detroit annexes Springwells Township east of Brooklyn Street.

• April 2, 1850 – Greenfield Township annexes another section of Springwells Township.

• February 12, 1857 – Detroit annexes Springwells Township east of Grand Boulevard.

• March 25, 1873 – Springwells Township annexes back section of Greenfield Township south of Tireman

• May 28, 1875 – Postmaster general changes name of Dearbornville post office to Dearborn post office, hence changing the city's name.

• 1875 – Detroit Arsenal closed.

• 1875 – Detroit annexes another section of Springwells Township.

• 1876 – William A. Nowlin writes The Bark Covered House in honor of country's 100th birthday.

• June 20, 1884 – Detroit annexes Springwells Township east of Livernois.

• 1889 – First telephone installed in Dearborn at St. Joseph's retreat.

Incorporation as village• March 24, 1893 – Village of Dearborn incorporates.

• 1906 – Detroit annexes another section of Springwells Township.

• 1916 - Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford move to Dearborn.

• 1916 – Detroit annexes more of Springwells Township, forming Dearborn's eastern boundary.

• 1917 – Rouge "Eagle" Plant opens.

• November 1, 1919 – The first house numbering ordinance in Dearborn starts. Residents required to place standard plate number on right side of the main house entrance five feet up.

• December 9, 1919 – Springwells Township incorporates as village of Springwells.

• October 16, 1922 – Springwells Township annexes small section of Dearborn Township east of present-day Greenfield Road.

• December 27, 1923 – Voters approve incorporation of Springwells as a city. It officially became a city April 7, 1924.

• September 9, 1924 – Village of Warrendale incorporates.

• November 1924 – Ford Airport opens.

• April 6, 1925 – Warrendale voters and residents of remaining Greenfield Township approve annexation by Detroit.

• May 26, 1925 – Village of Dearborn annexes large portion of Dearborn Township.

• December 23, 1925 – Springwells changes name to city of Fordson.

• February 15, 1926 – First U.S. airmail delivery made, going from Ford Airport in Dearborn to Cleveland.

• September 14, 1926 – Election approves incorporation of village of Inkster. Unincorporated part of Dearborn Township split into two unconnected sections.

• October 11, 1926 – Only dirigible to ever moor in Dearborn docks at Ford Airport.

Reincorporation as city• February 14, 1927 – Village of Dearborn residents approve vote to become a city.

• June 12, 1928 – Voters in Dearborn, Fordson and part of Dearborn Township vote to consolidate into one city.

• January 9, 1929 – Clyde Ford elected as first mayor of Dearborn.

• 1929 – Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village opens.

• July 1, 1931 – Dearborn Inn opens as one of the first airport hotels in world.

• March 7, 1932 – Ford Hunger March crosses Dearborn city limits. Four marchers are shot to death by police and Ford service men.

• 1936 – John Carey becomes mayor of Dearborn.

• June 19, 1936 – Montgomery Ward opens in Dearborn.

• May 26, 1937 – Harry Bennett's Ford "service" men beat United Auto Workers (UAW) official Richard Frankensteen in the Battle of the Overpass

• June 21, 1941 – Ford Motor Company signs its first union contract.

• 1939 – The Historic Springwells Park Neighborhood is established by Edsel B. Ford to provide company executives and auto workers with upscale housing accommodations.

• January 6, 1942 – Orville L. Hubbard takes office as mayor of Dearborn for first time.

• April 7, 1947 – Henry Ford dies.

• October 20, 1947 – Dearborn City Council approves purchase of land near Milford, Michigan for what would become Camp Dearborn. First section of camp opens following year.

• October 21, 1947 – Ford Airport officially closes.

• 1950 – First Pleasant Hours senior citizen group formed.

• 1950 – Dearborn Historical Museum formally established.

• January 1953 – Oakwood Hospital formally opened and dedicated.

• April 22, 1958 – Election held to annex part of South Dearborn Township to Dearborn. Proposal fails.

• 1959 – University of Michigan (Dearborn Campus) opens.

• April 6, 1959 – Election held to annex part of North Dearborn Township to Dearborn. Proposal fails.

• 1962 – St. Joseph's retreat closed and razed

• 1962 – New Henry Ford Community College campus dedicated.

• November 9, 1962 – Ford Rotunda burns down

• 1967 – Dearborn Towers in Clearwater, Florida opens.

• March 2, 1976 – Fairlane Town Center opens.

• 1978 – John B. O' Reilly, Sr. becomes mayor of Dearborn

• November 6, 1981 – Cable Television reaches first home in Dearborn, on Abbot Street.

• December 16, 1982 – Orville Hubbard dies.

• 1986 – Michael Guido becomes mayor of Dearborn.

• 1993 – Michael Guido is the first mayor to run unopposed.

• 2006 – Michael Guido dies at the age of 52 during his 6th term, the only mayor to die in office.

• 2006 – John B. O'Reilly, Jr. is to become temporary Mayor. O'Reilly's father was the mayor who had preceded Mayor Guido.

• 2007 – John B. O'Reilly, Jr. is elected mayor of Dearborn winning 93.97% of the vote.

• 2008 – John B. O'Reilly, Sr. dies at the age of 89; he was Mayor of Dearborn (1978–1985) and also served as Chief of Police for 11 years.

See also• History of the Middle Eastern people in Metro Detroit

References1. "City of Dearborn, Michigan". City of Dearborn, Michigan. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

2. "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jan 3, 2019.

3. "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

4. Jump up to:a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 16, 2019.

5. "Dearborn". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

6. Population of Michigan Cities, Villages, Townships, and Remainders of Townships.

http://www.michigan.gov.

7. America's Story, Explore the States: Michigan (2006). Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield VillageArchived 2009-10-14 at the Wayback Machine Library of Congress Retrieved on May 2, 2007.

8. State of Michigan: MI Kids (2006).Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village Archived 2010-12-07 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on May 2, 2007.

9. "History" Archived 2007-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Dearborn Area Living, accessed 15 May 2010

10. Loewen, James W. (2005). Sundown Towns. The New Press. pp. 110–112. ISBN 156584887X.

11. "Arab American National Museum of Arab American History, Culture & Art". Arabamericanmuseum.org. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

12. Woeste, Victoria Saker (February 9, 2019). "Why Ford needs to grapple with its founder's anti-Semitism". Washington Post.

13. Eisenstein, Paul A. (February 4, 2019). "Mayor's attempt to censor local article about Henry Ford's anti-Semitism draws national attention". CNBC.

14. Stanton, Jonathon (February 4, 2019). "Dearborn Historical Commission urges mayor to release article on Henry Ford and the Dearborn Independent". Press and Guide.

15. Buttle and Tuttle Ltd (2000–2008). "Wayne County island place names". Archived from the original on May 27, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

16. Heritage Newspapers (2009). "Dearborn Area Living: rivers, creeks, ditches". Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

17. Camp Dearborn Archived 2009-08-06 at the Wayback Machine, Dearborn city website

18. "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

19. "MI Dearborn". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

20. "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

21. "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

22. "Dearborn (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". census.gov. Archived from the originalon 2014-01-04.

23. Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov.

24. Maltese In Detroit, Diane Gale Andreassi, Larry Zahra, Arcadia Publishing, Feb 28, 2011, p. 47

25. Rev. Horace L. Sheffield, III, Denounces 'Residents Only' Policy at New Dearborn Civic Center as Racist Attempt to Limit Access by African-Americans, PR Newswire, HighBeam Research[dead link]

26. Population and Household Estimates for Southeast Michigan July 2014, SEMCOG, July 2014

27. "Dearborn, Michigan: America's Muslim Capital". Planetizen: The Urban Planning, Design, and Development Network.

28. of Citizenship, University of Michigan[dead link]

29. The Arab Population: Census Bureau, 2000, pp. 7–8, accessed 15 Apr 2008

30. Raz, Guy. "Lebanese-Americans Are Angry and Anxious", National Public Radio. August 8, 2006. Retrieved on March 27, 2013.

31. Michigan statistics – Arab Institute of America Archived 2010-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

32. Pierre M. Atlas. "Living together peacefully in heart of Arab America". commongroundnews.org. Archived from the original on 2010-10-13. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

33. "Islamic Center of America - Dearborn, Michigan - Mosques on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com.

34. Karoub, Jeff. "Oasis of Arab culture sits comfortably in Dearborn, Michigan." Chicago Sun-Times. August 6, 2011. Retrieved on November 20, 2012.

35. "Contact Ford Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine." Ford Motor Company. Retrieved on November 7, 2009.

36. "City of Dearborn 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). p. 186.

37. Locations: Detroit (Dearborn) Archived 2012-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Spring Arbor University, accessed November 8, 2012

38. CMU in Dearborn, Michigan, CMU Global Campus, Central Michigan University, accessed November 8, 2012

39. "Dearborn Public Schools". Dearborn Public Schools. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

40. "Westwood Community Schools." Michigan Department of Information Technology Center for Geographic Information. Retrieved on May 4, 2017.

41. "Zoning Map Archived 2016-12-25 at the Wayback Machine." City of Dearborn. Retrieved on May 4, 2017.

42. "Home." Muslim American Youth Academy. Retrieved on November 1, 2015. The address is "19500 Ford Road, Dearborn, MI 48128, United States"

43. "School History – St. Alphonsus Schools Alumni Dearborn, MI". Stalsalumni.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-02. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

44. Pratt, Chastity, Patricia Montemurri, and Lori Higgins. "PARENTS, KIDS SCRAMBLE AS EDUCATION OPTIONS NARROW." Detroit Free Press. March 17, 2005. A1 News. Retrieved on April 30, 2011. "School closings announced Wednesday by the Archdiocese of Detroit doomed eight high schools in Detroit and neighboring suburbs and will shutter 10 elementary schools, including historic landmarks such as St. Alphonsus Elementary in Dearborn and St. Florian Elementary in Hamtramck."

45. "GEE Academies." Global Educational Excellence. Retrieved on September 1, 2015.

46. "Hours/About Us." (Archive) Dearborn Public Library. Retrieved on November 15, 2013.

47. "A LOOK AT THE Bryant Branch." (Archive) Dearborn Public Library. Retrieved on November 15, 2013.

48. "A LOOK AT THE Henry Ford Centennial Library." (Archive) Dearborn Public Library. Retrieved on November 15, 2013.

49. "A LOOK AT THE Esper Branch." (Archive) Dearborn Public Library. Retrieved on November 15, 2013.

50. "City of Dearborn".

51. "City of Dearborn Council President".

52. Guide, Press and. "pressandguide.com - Serving Dearborn and Dearborn Heights since 1918". Press and Guide.

53. "About Us Archived 2013-05-20 at the Wayback Machine." The Arab American News. Retrieved on September 22, 2013.

54. "Michigan's Rima Fakih Wins Miss USA Pageant". CBS News. May 16, 2010.

55. Brayton, Ed (2010-07-22). "Dearborn police accused of violating First Amendment". The Michigan Messenger. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

56. Light, Jonathan (September 25, 2010). "Acts-17 Group Acquitted of Inciting Crowd". Dearborn Free Press. DEARBORN, Michigan. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

57. "Dearborn ordered to apologize for arrests of Christian missionaries at Arab Fest".

58. Jill Lawrence, "Sharron Angle on Sharia Religious Law: It's Already Supplanting the Constitution", Politics Daily, 7 October 2010

59. "Sharron Angle Claims Dearborn, Michigan Ruled by Sharia Law", The Atlantic

60. "Jones Released from Jail After Paying 'Peace Bond'". WJBK. Dearborn. 2011-04-22. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

61. "Terry Jones Amicus Brief", ACLU Michigan Website, accessed 1 September 2011

62. WDIV. "Crowds Bust Barricades At Pastor's Speech In Dearborn". ClickOnDetroit.

63. "Riot Police Respond as Counter-Protesters Storm Terry Jones' Demonstration". Dearborn, Michigan Patch.

64. "Riot police were called in Friday evening after Gainesville pastor Terry Jones taunted protesters here, prompting the protesters to rush past a police barricade and begin throwing water bottles and shoes". Gainesville.com. 2011-04-29. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

65. "6 Arrested as Mob Rushes Terry Jones on Way to Arab Festival in Dearborn". Dearborn, Michigan Patch.

66. WARIKOO, Niraj (Jun 19, 2011). "Christian missionaries take on Muslims, Catholics at Arab International Festival". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

67. Wattrick, Jeff (November 11, 2011). "Judge vacates 'breach of peace' judgement against Terry Jones". MLive.com. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

68. Warikoo, Niraj (April 7, 2012). "Fla. pastor Terry Jones: Islam's goal is 'world domination'". USA Today.

Further reading• Barrow, Heather B. (2015). Henry Ford's Plan for the American Suburb: Dearborn and Detroit. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press.

• Cantor, George (2005). Detroit: An Insiders Guide to Michigan. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03092-2.

• Fisher, Dale (2003). Building Michigan: A Tribute to Michigan's Construction Industry. Grass Lake, MI: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-24-7.

• Fisher, Dale (2005). Southeast Michigan: Horizons of Growth. Grass Lake, MI: Eyry of the Eagle Publishing. ISBN 1-891143-25-5.

• Hill, Eric J. and John Gallagher (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3120-3.

• Rignall, Karen (graduate student). "Building an Arab-American Community in Dearborn." University of Michigan. Volume 5, Issue 1, Fall 1997.

External links• City of Dearborn

• Dearborn Chamber of Commerce

• Dearborn, Michigan at Curlie