Part 2 of 2

The IraqComm system

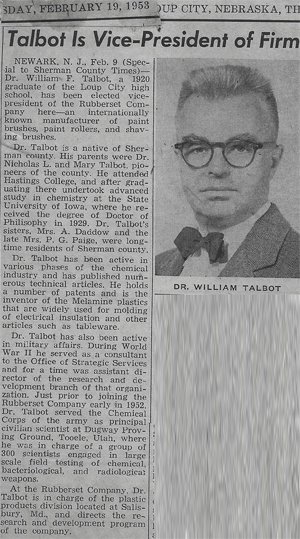

The IraqComm systemWith DARPA-funded research, SRI contributed to the development of speech recognition and translation products[82][83] and was an active participant in DARPA's Global Autonomous Language Exploitation (GALE) program.[83] SRI developed DynaSpeak speech recognition technology which was used in the handheld VoxTec Phraselator, allowing U.S. soldiers overseas to communicate with local citizens in near real time.[84] SRI also created translation software for use in the IraqComm, a device which allows two-way, speech-to-speech machine translation between English and colloquial Iraqi Arabic.[85]

In medicine and chemistry, SRI developed dry-powder drugs,[86] laser photocoagulation (a treatment for some eye maladies),[87] remote surgery (also known as telerobotic surgery), bio-agent detection using upconverting phosphor technology, the experimental anticancer drugs Tirapazamine and TAS-108, ammonium dinitramide (an environmentally benign oxidizer for safe and cost-effective disposal of hazardous materials), the electroactive polymer ("artificial muscle"), new uses for diamagnetic levitation, and the antimalarial drug Halofantrine.[26][88]

SRI performed a study in the 1990s for Whirlpool Corporation that led to modern self-cleaning ovens.[89] In the 2000s, SRI worked on Pathway Tools software for use in bioinformatics and systems biology to accelerate drug discovery using artificial intelligence and symbolic computing techniques.[90] The software system generates the BioCyc database collection, SRI's growing collection of genomic databases used by biologists to visualize genes within a chromosome, complete biochemical pathways, and full metabolic maps of organisms.[91]

Early 21st centurySRI researchers made the first observation of visible light emitted by oxygen atoms in the night-side airglow of Venus, offering new insight into the planet's atmosphere.[92][93][94] SRI education researchers conducted the first national evaluation of the growing U.S. charter schools movement. For the World Golf Foundation, SRI compiled the first-ever estimate of the overall scope of the U.S. golf industry's goods and services ($62 billion in 2000), providing a framework for monitoring the long-term growth of the industry.[95][96] In April 2000, SRI formed Atomic Tangerine, an independent consulting firm designed to bring new technologies and services to market.[97]

A building on SRI International's campus

A building on SRI International's campusIn 2006, SRI was awarded a $56.9 million contract with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to provide preclinical services for the development of drugs and antibodies for anti-infective treatments for avian influenza, SARS, West Nile virus and hepatitis.[98] Also in 2006, SRI selected St. Petersburg, Florida, as the site for a new marine technology research facility targeted at ocean science, the maritime industry and port security; the facility is a collaboration with the University of South Florida College of Marine Science and its Center for Ocean Technology.[99][100][101] That facility created a new method for underwater mass spectrometry, which has been used to conduct "advanced underwater chemical surveys in oil and gas exploration and production, ocean resource monitoring and protection, and water treatment and management" and was licensed to Spyglass Technologies in March 2014.[102]

In December 2007, SRI launched a spin-off company, Siri Inc., which Apple acquired in April 2010.[103] In October 2011, Apple announced the Siri personal assistant as an integrated feature of the Apple iPhone 4S.[104] Siri's technology was born from SRI's work on the DARPA-funded CALO project, described by SRI as the largest artificial intelligence project ever launched.[105] Siri was co-founded in December 2007 by Dag Kittlaus (CEO), Adam Cheyer (vice president, engineering), and Tom Gruber (CTO/vice president, design), together with Norman Winarsky (vice president of SRI Ventures). Investors included Menlo Ventures and Morgenthaler Ventures.[106]

For the National Science Foundation (NSF), SRI operates the advanced modular incoherent scatter radar (AMISR), a novel relocatable atmospheric research facility.[107] Other SRI-operated research facilities for the NSF include the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and the Sondrestrom Upper Atmospheric Research Facility in Greenland. In May 2011, SRI was awarded a $42 million contract to operate the Arecibo Observatory from October 1, 2011 to September 30, 2016.[108] The institute also manages the Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Northern California, home of the Allen Telescope Array.[109]

In February 2014, SRI announced a "photonics-based testing technology called FASTcell" for the detection and characterization of rare circulating tumor cells from blood samples. The test is aimed at cancer-specific biomarkers for breast, lung, prostate, colorectal and leukemia cancers that circulate in the blood stream in minute quantities, potentially diagnosing those conditions earlier.[110][111]

In September 2018, NSF announced that SRI International will be rewarded $4.4 million to establish the backbone organization of a national network.[112]

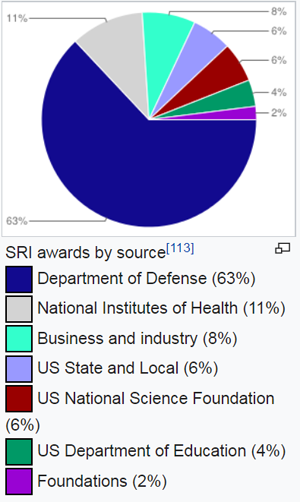

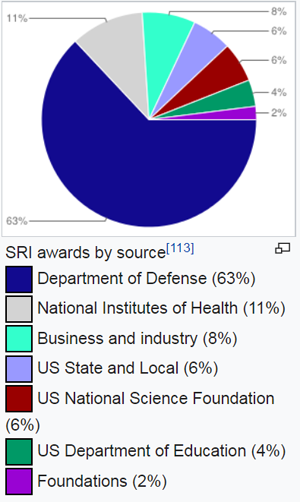

Description SRI awards by source[113]Employees and financials

SRI awards by source[113]Employees and financialsAs of February 2015, SRI employs approximately 2,100 people.[1] In 2014, SRI had about $540 million in revenue.[1] In 2013, the United States Department of Defense consisted of 63% of awards by value; the remainder was composed of the National Institutes of Health (11%); businesses and industry (8%); other United States agencies (6%); the National Science Foundation (6%); the United States Department of Education (4%); and foundations (2%).[113]

As of February 2015, approximately 4,000 patents have been granted to SRI International and its employees.[7]

FacilitiesSRI is primarily based on a 63-acre (0.25 km2; 0.10 sq mi) campus located in Menlo Park, California, which is considered part of Silicon Valley. This campus encompasses 1,300,000 square feet (120,000 m2) of office and lab space.[114] In addition, SRI has a 254-acre (1.028 km2; 0.397 sq mi) campus in Princeton, New Jersey, with 600,000 square feet (56,000 m2) of research space. There are also offices in Washington, D.C., and Tokyo, Japan. In total, SRI has 2,300,000 square feet (210,000 m2) of office and laboratory space.[114]

OrganizationSRI International is organized into seven units (generally referred to as divisions) that focus on specific subject areas.[115]

Name / Research area / Reference

Advanced Technology and Systems / SRI's largest organizational unit manages complex projects for government and commercial clients in areas such as chemistry, physics, and materials science; geospace studies and space and marine technology; surveillance and remote sensing; applied optics and secure circuits; and robotics, medical devices, and nanotechnology. / [116]

Biosciences / SRI Biosciences works with academic, commercial, foundation, and government clients and partners to bring new medicines to market through basic research, pharmaceutical discovery, pre-clinical development, and clinical translation. SRI has helped move more than 100 drugs into clinical trials. / [117][118]

Education / SRI Education works with government officials, private foundations, and commercial clients to provide research-based analysis and evaluation of programs to identify trends, understand outcomes, and guide public policy and practice. Focus areas include early learning, educational technology, social and emotional learning, teacher quality assessments, college and career readiness, and large-scale surveys. / [119]

Global Partnerships / It comprises three groups: the Center for Science, Technology, and Economic Development, the Center for Innovation Leadership, the Energy Center, and a team focused on R&D programs for international clients. / [120]

Information and Computing Sciences / For its government and commercial clients, this division conducts R&D activities to understand the computational principles underlying intelligence in humans and machines, and to create computer-based systems that solve problems. ICS is organized into four laboratories, one of which is SRI's Artificial Intelligence Center. The division focuses on artificial intelligence, speech recognition, natural language processing, bioinformatics, and computer security. / [121]

Mission Solutions / Mission Solutions performs technology and services in support U.S. government-deployed systems. The division focuses on information operations, navigation and survivability systems, and systems and signal technology. / [122]

Products and Solutions / This SRI division transitions R&D technology into products for its government and commercial clients. It maintains a portfolio that includes biometric identification systems, real-time video processing systems, integrated video and sensor exploitation solutions, and video test tools. / [123]

Staff members and alumniMain article: List of SRI International people

William A. Jeffrey

William A. Jeffrey Douglas Engelbart

Douglas EngelbartSRI has had a chief executive of some form since its establishment. Prior to the split with Stanford University, the position was known as the director; after the split, it is known as the company's president and CEO. SRI has had nine so far, including William F. Talbot (1946–1947),[15] Jesse E. Hobson (1947–1955),[124] E. Finley Carter (1956–1963),[125] Charles Anderson (1968–1979),[126] William F. Miller (1979–1990),[127] James J. Tietjen (1990–1993),[128] William P. Sommers (1993–1998)[129]

Curtis Carlson (1998–2014)[130] and most recently, William A. Jeffrey (2014–present).[131]

SRI also has a board of directors since its inception, which has served to both guide and provide opportunities for the organization. The current board of directors includes Samuel Armacost (Chairman of the Board Emeritus), Mariann Byerwalter (chairman), William A. Jeffrey, Charles A. Holloway (vice chairman), Vern Clark, Robert L. Joss, Leslie F. Kenne, Henry Kressel, David Liddle, Philip J. Quigley, Wendell Wierenga and John J. Young, Jr.[132]

Its notable researchers include Elmer Robinson (meteorologist), co-author of the 1968 SRI report to the American Petroleum Institute (API) on the risks of fossil fuel burning to the global climate.[133] Many notable researchers were involved with the Augmentation Research Center. These include Douglas Engelbart, the developer of the modern GUI;[134] William English, the inventor of the mouse;[135] Jeff Rulifson, the primary developer of the NLS;[136] Elizabeth J. Feinler, who ran the Network Information Center;[137] and David Maynard, who would help found Electronic Arts.[138]

The Artificial Intelligence Center has also produced a large number of notable alumni, many of whom contributed to Shakey the robot;[139] these include project manager Charles Rosen[140] as well as Nils Nilsson,[141] Bertram Raphael,[139] Richard O. Duda,[142] Peter E. Hart,[142] Richard Fikes[143] and Richard Waldinger.[144] AI researcher Gary Hendrix went on to found Symantec.[145][146] Current Yahoo! President and CEO Marissa Mayer performed a research internship in the Center in the 1990s.[147] The CALO project (and its spin-off, Siri) also produced notable names including C. Raymond Perrault and Adam Cheyer.[148][149]

Several SRI projects produced notable researchers and engineers long before computing was mainstream. Early employee Paul M. Cook founded Raychem.[150] William K. MacCurdy developed the Hydra-Cushion freight car for Southern Pacific in 1954;[27] Hewitt Crane and Jerre Noe were instrumental in the development of Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting;[40] Harrison Price helped The Walt Disney Company design Disneyland;[22] James C. Bliss developed the Optacon;[151] and Robert Weitbrecht invented the first telecommunications device for the deaf.[152][153]

Spin-off companiesMain article: List of SRI International spin-offs

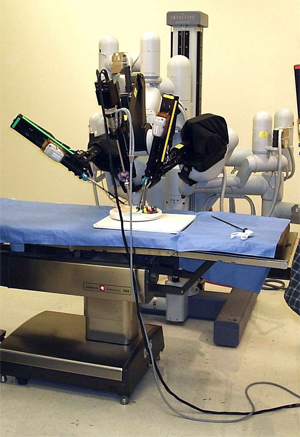

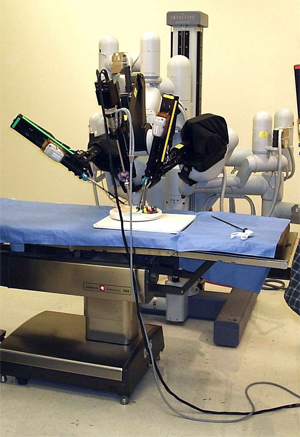

Intuitive Surgical's robotic surgery system, the da Vinci Surgical System

Intuitive Surgical's robotic surgery system, the da Vinci Surgical SystemWorking with investment and venture capital firms, SRI and its former employees have launched more than 60 spin-off ventures[154] in a wide range of fields, including Siri (acquired by Apple), Tempo AI (acquired by Salesforce.com), Redwood Robotics (acquired by Google), Desti (acquired by HERE), Grabit, Kasisto, Artificial Muscle, Inc. (acquired by Bayer MaterialScience), Nuance Communications, Intuitive Surgical, Ravenswood Solutions, and Orchid Cellmark.[4][155][156]

Former SRI staff members have also established new companies. In engineering and analysis, for example, notable companies formed by SRI alumni include Weitbrecht Communications,[157] Exponent and Raychem.[156] Companies in the area of legal, policy and business analysis include Fair Isaac Corporation, Global Business Network and Institute for the Future.[156]

Research in computing and computer science-related areas led to the development of many companies, including Symantec, the Australian Artificial Intelligence Institute, E-Trade, and Verbatim Corporation. Wireless technologies spawned Firetide and venture capital firm enVia Partners.[156] Health systems research inspired Telesensory Systems.[156][158]

See also• San Francisco Bay Area portal

References

Notes1. "About Us". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

2. "Products and Solutions: Technologies for License". SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

3. "Products and Solutions". SRI International. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

4. "SRI Ventures". SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

5. "SRI International Completes Integration of Sarnoff Corporation" (Press release). SRI International. 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2002-07-01.

6. "SRI International". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

7. "About Us". SRI International. 2014-10-20. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

8. Nielson, p. 1-1

9. Nielson, p. B-1

10. Nielson, p. B-2

11. Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 6, 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

12. Nielson, p. B-3

13. Nielson, p. B-4

14. Gibson, SRI: The Founding Years, pp. 111-112

15. Lowen, Rebecca (July–August 1997). "Exploiting a Wonderful Opportunity". Stanford Magazine. Stanford Alumni Association. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

16. Gibson, SRI: The Founding Years, pp. 98-99

17. Gibson, SRI: The Founding Years, p. 108

18. "Tide". SRI International. Archived from the original on 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

19. Nielson, pp. 9-18 - 9-21

20. Gibson, Weldon B. (1986). SRI: The Take-Off Days. Los Altos, California: Stanford Research Institute. pp. 48, 55, 149, 168, 181. ISBN 978-0-86576-103-2.

21. Nielson, pp. 14-17 - 14-20

22. "Disneyland". Timeline of Innovations. SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

23. Katz, Leslie (2010-07-19). "Star-studded celebration of Disneyland's 55th year". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

24. "Timeline of SRI International Innovations: 1940s - 1950s". SRI International. Archived from the original on 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

25. McLaughlin, p. 39

26. McLaughlin, p. 40

27. Nielson, pp. 6-1 - 6-3

28. "Railroad Hydra-Cushion". Timeline of Innovations. SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

29. Nielson, p. 2-8

30. Nielson, p. 2-1

31. "Timeline of Innovations: Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

32. "Magnetic Ink Character Recognition Line Law & Legal Definition". USLegal. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

33. "Douglas C. Engelbart". Hall of Fellows. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

34. "Douglas Engelbart, Foresight Advisor, Is Awarded National Medal of Technology". Foresight Update. 43. Foresight Institute. 2000-12-30.

35. "How the mouse got its name". BBC News. 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

36. DARPA, pp. 76-77

37. McLaughlin, p. 37

38. "Milestones: Liquid Crystal Display, 1968". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

39. "All-Magnetic Logic Computer". Timeline of Innovations. SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

40. Markoff, John (2008-06-21). "Hewitt D. Crane, 81, Early Computer Engineer, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

41. Movie "Shakey". Stanford Research Institute. 1969. In 1966, the Stanford Research Institute created the first mobile robot that could reason about its surroundings.

42. "Shakey". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

43. Sutton, Chris (2004-09-14). "Internet Began 35 Years Ago at UCLA with First Message Ever Sent Between Two Computers". UCLA. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

44. DARPA, pp. 79-83

45. Lewis, Mark G.; Garcia-Luna-Aceves, J. J. (1987-10-19). "Packet-Switching Applique for Tactical VHF Radios". Crisis Communications: The Promise and Reality. IEEE MILCOM 1987. 2: 0449–0455. doi:10.1109/MILCOM.1987.4795249.

46. "Over-the-Horizon Radar". SRI International. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

47. Thomason, Joseph F. (2005-04-14). "Development of Over-the-Horizon Radar in the United States". United States Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

48. "Telecommunications Tools for the Deaf". Timeline of Innovations. SRI International. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

49. "Deafnet". CNET. 2010-10-26. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

50. Ogg, Erica (2007-11-08). "'Internet van' helped drive evolution of the Web". CNET. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

51. "Timeline of innovations: Internetworking: The First Three-Network Transmission". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

52. "Elizabeth J. Feinler". SRI Alumni Hall of Fame. 2000. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

53. "Underground Newspapers on Microfilm: Peninsula Observer". Herb Caen Magazines and Newspapers Center. San Francisco Public Library. 2010-06-05. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

54. McLaughlin, p. 38

55. Leslie, Stuart W. (1994-04-15). "Chapter 9. The Days of Reckoning: March 4 and April 3". The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231079594.

56. Targ, R.; Puthoff, H. (1974-10-18). "Information transmission under conditions of sensory shielding". Nature. 251 (5476): 602–7. doi:10.1038/251602a0. PMID 4423858.

57. Puthoff, H.; Targ, R. (March 1976). "A perceptual channel for information transfer over kilometer distances: Historical perspective and recent research". Proceedings of the IEEE. 64 (3): 329–354. doi:10.1109/proc.1976.10113.

58. May, EC (March 1996). "The American Institutes for Research review of the Department of Defense's STAR GATE program: A commentary". Journal of Parapsychology (commentary). 60: 3–23. Also published in "The American Institutes for Research review of the Department of Defense's STAR GATE program: A commentary". Journal of Scientific Exploration. 10 (1): 89–107. 1996.

59. Jayanti, Vikram (June 13, 2013). "Never mind the NSA: Uri Geller is the real spy story". The Guardian. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

60. Scott, C. (July 29, 1982). "No "remote viewing"". Nature. 298 (5873): 414. doi:10.1038/298414c0., Marks, D.; Scott, C. (1986-02-06). "Remote viewing exposed". Nature. 319 (6053): 444. doi:10.1038/319444a0. PMID 3945330.

61. Waller, Douglas (1995-12-11). "The Vision Thing". Time. p. 45. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

62. "About VALS: The VALS Story". Strategic Business Insights. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

63. "Vals". Sric-Bi. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

64. Nielson, pp. 11-7 - 11-10

65. Lunt, Teresa F.; Denning, Dorothy E.; Schell, Roger R.; Heckman, Mark; Shockley, William R. (June 1990). "The SeaView Security Model" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. IEEE Computer Society. 16 (6).

66. Lamport, Leslie (1986). LaTeX: A Document Preparation System. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-15790-1. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

67. "Ventures: PacketHop". SRI International. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

68. "SRI International of Menlo Park Wins Patent Battle Over Enterprise Network Intrusion Detection Technology". Intellectual Property Today. 2008-10-24. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

69. Saffiotti, Alessandro; Ruspini, E.; Konolige, Kurt G. (March 1993). "A Fuzzy Controller For Flakey, An Autonomous Mobile Robot". SRI International. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

70. "CARMEL vs. Flakey: A Comparison of Two Robots". University of Michigan and SRI International. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.87.1641.

71. "100 oldest .com domains". iWhois.com. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

72. Myers, Karen L. "PRS-CL: A Procedural Reasoning System". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

73. "SRI Technology At Core of New U.S. Postal Service Letter Sorting System". 1997-09-03. Archived from the original on 2011-04-20. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

74. "INCON". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

75. "Deployable Force-on-Force Instrumented Range System". SRI International. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

76. "Centibots: The 100 Robots Project". Artificial Intelligence Center. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

77. "Centibots: The 100 Robots Project". University of Washington Computer Science & Engineering: Robotics and State Estimation Lab. Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

78. Ackerman, Elise (2004-01-15). "Centibot army drills for action for the military". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

79. Delio, Michelle (2003-08-04). "LinuxWorld Opens Hunting Season". Wired. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

80. "BotHunter aims to find bots for free".

http://www.securityfocus.com.

81. "About BotHunter".

http://www.bothunter.net.

82. DARPA, p. 99

83. Anderson, Nate (2006-11-09). "Defense Department funds massive speech recognition and translation program". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

84. Mieszkowski, Katharine (2003-04-07). "How do you say "regime change" in Arabic?". Salon. p. 2. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

85. Piquepaille, Roland (2006-06-04). "IraqComm computer cracks language barriers". ZDNet. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

86. "SRI International Licenses Drug Formulation Process to Dura Pharmaceuticals". SRI International. 1997-07-01. Archived from the original on 2011-04-20. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

87. US 3703176

88. Nielson, pp. 10-3 - 10-5

89. Nielson, p. 11-1

90. "Pathway Tools Information Site". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

91. "BioCyc". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

92. "SRI International Makes First Observation of Atomic Oxygen Emission in the Night Airglow of Venus" (Press release). SRI International. 2001-01-18. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

93. "SRI International Celebrates 50 Years of Molecular Physics Discoveries" (Press release). SRI International. 2006-08-06. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

94. "Discovery of the Atomic Oxygen Green Line in the Venus Night Airglow". Science. 2001-01-19. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

95. "Golf 20/20 Overview". World Golf Foundation. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

96. "U.S. Golf Economy Measures $62 Billion, Says New Report By SRI International for the World Golf Foundation's Golf 20/20 Initiative" (Press release). SRI International. 2002-11-14. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

97. "SRI International Launches Spin-Off Company AtomicTangerine, The First Venture Consulting Firm to Target E-business". SRI International. 2000-04-19. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

98. Lauerman, John (2006-11-07). "SRI Wins U.S. Contract to Develop Drugs for Bird Flu". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2012-04-15.

99. "SRI International Selects St. Petersburg, Florida for New Marine Technology R&D Facility" (Press release). SRI International. 2006-11-30. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

100. "City Breaks Ground on SRI International's St. Petersburg Facility" (Press release). SRI International. 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

101. "SRI Opens New Research Facility at the Port of St. Petersburg". Florida Technology Journal. 2010-01-11. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

102. "Spyglass Technologies Receives Exclusive License to Commercialize SRI International's Underwater Mass Spectrometer" (Press release). SRI International. 2014-03-19. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

103. Hay, Timothy (2010-04-28). "Apple Moves Deeper Into Voice-Activated Search With Siri Buy". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

104. "Apple's Siri voice assistant based on extensive research". CNN. 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

105. "Siri Launches Virtual Personal Assistant for iPhone 3GS" (Press release). SRI International. 2010-02-05. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

106. Lardinois, Frederic (2008-10-13). "Semantic Stealth Startup Siri Raises $8.5 Million". Readwriteweb.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-18. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

107. "Advanced Modular Incoherent Scatter Radar". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

108. "SRI International Selected by the National Science Foundation to Manage Arecibo Observatory"(Press release). SRI International. 2011-06-02. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

109. Robert Sanders (April 13, 2012). "UC Berkeley passes management of Allen Telescope Array to SRI". UC Berkeley NewsCenter. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

110. "SRI International launches FASTcell cancer cell screening system". Optics. 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

111. Barclay, Rachel (2014-02-28). "Novel Blood Test Can Find One Cancer Cell Among Millions". HealthlineNews. Healthline. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

112. "NSF Awards Aim to Expand STEM Participation". SIGNAL Magazine. 2018-09-12. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

113. "SRI Fact Sheet" (PDF). SRI International. March 2014. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

114. "Specialized Facilities". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

115. "Our Organization". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

116. "Advanced Technology and Systems Division". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

117. "SRI Biosciences". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

118. Potera, Carol (2008-08-01). "SRI Boasts Abilities in Early- and Late-Stage R&D". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Company Updates. 28 (14). Mary Ann Liebert. p. 18. ISSN 1937-8661. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

119. "SRI Education". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

120. "Global Partnerships". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

121. "Information and Computing Sciences". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

122. "Mission Solutions Division". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

123. "Products and Solutions". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

124. "Alumni Hall of Fame: Previous Years: J. E. Hobson". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

125. "E. Finley Carter". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

126. "Charles Anderson". San Francisco Chronicle. 2009-04-21. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

127. "Faculty Profiles: William F. Miller". Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

128. "Dean Emeritus of Stevens Institute of Technology Dr. James J. Tietjen Joins SynQuest Board"(Press release). The Free Library by Farlex. 2000-11-30. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

129. "Dr. William P. "Bill" Sommers". San Francisco Chronicle. 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

130. "Our People: Curtis R. Carlson". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

131. "Our People: William Jeffrey". SRI International. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

132. "Our People: Board of Directors". SRI International. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

133. "The Oil Industry Was Warned About Climate Change in 1968". Vice News. 15 April 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

134. "The Demo". Science and Technology in the Making: MouseSite. Stanford University. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

135. "Bill English". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-01-04. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

136. "Alumni Hall of Fame 2006: Johns Frederick (Jeff) Rulifson". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

137. "Alumni Hall of Fame 2000: Elizabeth J. Feinler". SRI International. 2000. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

138. David Maynard at MobyGames

139. Nilsson, Nils J. (2010). The Quest for Artificial Intelligence: A History of Ideas and Achievements (PDF). Stanford University.

140. Buchanan, Wyatt (2002-12-20). "Charles Rosen -- expert on robots, co-founder of winery". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

141. "AI's Hall of Fame" (PDF). IEEE Intelligent Systems. 26 (4): 5–15. 2011. doi:10.1109/MIS.2011.64.

142. "Alumni Hall of Fame 2008: Peter E. Hart". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

143. Fikes, Richard E (April 1971). "Monitored Execution of Robot Plans Produced by STRIPS" (PDF). SRI International. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

144. "Dr. Richard J. Waldinger". Artificial Intelligence Center. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

145. Spicer, Dag (2004-11-19). "Oral History of Gary Hendrix" (PDF). Computer History Museum. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

146. McLaughlin, p. 100

147. "Marissa Mayer Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

148. "International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Honors SRI's Raymond Perrault with Donald E. Walker Distinguished Service Award". SRI International. 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

149. Boran, Marie (2011-11-16). "iRobot". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

150. Bohning, James J. (2 April 1992). Paul M. Cook, Transcript of an Interview Conducted by James J. Bohning at San Carlos, California on 2 April 1992 (PDF). Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation.

151. Bliss, James C. (June 1966). "Contributors". IEEE Transactions on Human Factors in Electronics. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

152. "Robert H. Weitbrecht". Deaf Scientist Corner. Texas Women's University. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

153. Hevesi, Dennis (2009-08-22). "James Marsters, Deaf Inventor, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

154. "SRI Ventures". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

155. "Alphabetical List". SRI International. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

156. Nielson, p. F1-F4

157. Lang, Harry G (2000). A phone of our own: the deaf insurrection against Ma Bell. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1-56368-090-8.

158. "Ventures: Biotech/Medical". SRI International. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

Works cited• Nielson, Donald (2006). A Heritage of Innovation: SRI's First Half Century. Menlo Park, California: SRI International. ISBN 978-0-9745208-1-0.

• Gibson, Weldon B. (1980). SRI: The Founding Years. Los Altos, California: Stanford Research Institute. ISBN 978-0-913232-80-4.

• McLaughlin, John R.; Weimers, Leigh A.; Winslow, Wardell V. (2008). Silicon Valley: 110 Year Renaissance. Palo Alto, California: Santa Clara Valley Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-9649217-4-0.

• DARPA: 50 Years of Bridging The Gap. DARPA. 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-05-06.

Further reading[edit]

SRI history[edit]

• Carlson, Curtis R.; Wilmot, William W. (2006). Innovation: The Five Disciplines for Creating What Customers Want. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-33669-9.

• Lento, Thomas V (2006). Inventing the Future: 60 Years of Innovation at Sarnoff. Princeton, New Jersey: Sarnoff Corporation. ISBN 978-0-9785463-0-4.

• Gibson, Weldon B. (1986). SRI: The Take-Off Days. Los Altos, California: Stanford Research Institute. ISBN 978-0-86576-103-2.

Specific topics[edit]

• Crane, Hewitt; Kinderman, Edwin; Malhotra, Ripudaman (June 2010). A Cubic Mile of Oil. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 978-0-19-532554-6.

• Markoff, John (2005). What the Dormouse Said: How the 60s Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. New York: Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-03382-9.

• Hafner, Katie (1996). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet (with Matthew Lyon). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83267-8.

• Bowden, Mark (2011). WORM: The First Digital World War [about the Conficker computer worm]. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1983-4.

External links• SRI International website