Banaras Hindu University [Central Hindu College]by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/17/20

Banaras Hindu University

The seal of Banaras Hindu University, depicting Goddess Saraswati

Former name: Central Hindu College

Motto: Vidyayā'mritamașnute

Motto in English: "Knowledge imparts immortality"

Type: Public

Established: 1916; 104 years ago

Founders: Madan Mohan Malaviya; Annie Besant; Rameshwar Singh; Sir Sunder Lal

Chancellor: Giridhar Malaviya[1]

Vice-Chancellor: Rakesh Bhatnagar[2]

Rector: V. K. Shukla

Visitor: President of India

Students: 30,698[3]

Undergraduates: 15,746[3]

Postgraduates: 7,557[3]

Doctoral students: 4,555[3]

Location: Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

Campus: Multiple sites

Affiliations: ACU AIU NAAC UGC

Mascot: Goddess Saraswati

Website: bhu.ac.in

Coordinates: 25.2677203°N 82.9890695°E

Banaras Hindu University (Hindi: [kaʃi hind̪u viʃvəvid̪yaləy], BHU), formerly Central Hindu College, is a public central university located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. It was established jointly in 1916 by Maharaja of Darbhanga Rameshwar Singh[4],...

Maharaja Sir Rameshwar Singh Thakur GCIE KCB KBE (16 January 1860 – 3 July 1929) was the Maharaja of Darbhanga in the Mithila region from 1898 to his death. He became Maharaja on the death of his elder brother Maharaja Sir Lakshmeshwar Singh, who died without issue. He was appointed to the Indian Civil Service in 1878, serving as assistant magistrate successively at Darbhanga, Chhapra, and Bhagalpur. He was exempted from attendance at the Civil Courts and was appointed a Member of the Legislative Council of Bengal (MLC of Bengal) in 1885.

He was the first Indian appointed to the lieutenant governor's Executive Council.

He was a Member of the Council of India of the Governor General of India in 1899 and on 21 September 1904 was appointed a non-officiating member representing the Bengal Provinces, along with Gopal Krishna Gokhale from Bombay Province.

He was president of the Bihar Landholder's Association, president of the

All India Landholder's Association, president of Bharat Dharma Mahamandal,...

Bharat Dharma Mahamandala was a prominent Hindu organization founded by Pandit Din Dayalu Sharma in Hardwar in 1887, who also founded the Hindu College, Delhi, on May 15, 1899. Its objective was to bring together all leaders of the orthodox Hindu community and to work together for the preservation of Sanatan Dharma. The offshoots of the Mahamandala were the Sanatan Dharma Sabhas, founded for the defense of Hinduism from critics both within the community and outside it. In the early years of the 20th century, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya was very closely associated with the Mahamandala and the Sanatan Dharma movements.

-- Bharat Dharma Mahamandala, by GKToday

Sanātanī (सनातनी[1]) is a term used to describe Hindu movements that includes the ideas from the Vedas and the Upanishads while also incorporating the teachings of sacred hindu texts such as Ramayana and

Bhagavad Gita which itself is often being described as a concise guide to Hindu philosophy and a practical, self-contained guide to life.

Sanatana Dharma denotes duties (righteousness) performed according to one's spiritual (constitutional) identity as Ātman (Hinduism). Sanatana Dharma is presently a large facet of the collective synthesis of beliefs known as Hinduism. It often rejects previously long-established socio-religious systems based on interpretations of sectarian followers of an individual sant (saint or pontiff). The term was used by Gandhi in 1921 while describing his own religious beliefs.

-- Sanātanī, by Wikipedia

a member of the Council of State [Rajya Sabha, upper house of the bicameral Parliament of India], a trustee of the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta, president of the Hindu University Society, M.E.C. of Bihar and Orissa and Member of the Indian Police Commission (1902–03). He was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind medal in 1900. He was the only member of the India Police Commission who dissented with a report on requirements for police service, and suggested that the recruitment to the Indian Police Services should be through a single exam only to be conducted in India and Britain simultaneously. He also suggested the recruitment should not be based on colour or nationality. This suggestion was rejected by the India Police Commission.

Maharaja Rameshwar Singh was a Tantric and was known as Buddhist Siddha. He was considered a Rajarshi (sage king) by his people.

He was knighted a

Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE) on 26 June 1902, was promoted to a Knight Grand Commander (GCIE) in the 1915 Birthday Honours List and was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Civil Division (KBE) in the 1918 Birthday Honours List.

He was succeeded by his son, Sir Kameshwar Singh.

-- Rameshwar Singh, by Wikipedia

Madan Mohan Malaviya,...

Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya (25 December 1861 – 12 November 1946) was an Indian scholar, educational reformer and politician notable for his role in the Indian independence movement, as the

four times president of Indian National Congress and the founder of Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha [Hindu Mahasabha.

Assassination of Mahatma GandhiIn the 1940s, the Muslim League stepped up its demand for a separate Muslim state of Pakistan. Although the Congress strongly opposed religious separatism, the League's great popularity amongst Muslims forced the Congress leaders to hold talks with the League president, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Even though Savarkar agreed with Jinnah and recognised Hindus and Muslims to be separate nations, he condemned the secular Gandhi's overtures to hold talks with Jinnah and regain Muslim support for the Congress as appeasement. After communal violence claimed the lives of thousands in 1946, Savarkar claimed that Gandhi's adherence to non-violence had left Hindus vulnerable to armed attacks by militant Muslims. When the partition of India was agreed upon in June 1947 after months of failed efforts at power-sharing between the Congress and the League, the Mahasabha condemned the Congress and Gandhi for agreeing to the partition plan.

On January 30, 1948 Nathuram Godse shot Mahatma Gandhi three times and killed him in Delhi. Godse and his fellow conspirators Digambar Badge, Gopal Godse, Narayan Apte, Vishnu Karkare and Madanlal Pahwa were identified as prominent members of the Hindu Mahasabha. Along with them, police arrested Savarkar, who was suspected of being the mastermind behind the plot. While the trial resulted in convictions and judgments against the others, Savarkar was released on a technicality, even though there was evidence that the plotters met Savarkar only days before carrying out the murder and had received the blessings of Savarkar. The Kapur Commission in 1967 established that Savarkar was in close contact with the plotters for many months. Kapur Commission said,

All these facts taken together were destructive of any theory other than the conspiracy to murder (of Gandhiji) by Savarkar and his group.

-- Hindu Mahasabha, by Wikipedia

He was respectfully addressed as Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya and also addressed as Mahamana.

Malaviya strived to promote modern education among Indians and eventually cofounded

Banaras Hindu University (BHU) at Varanasiin 1916, which was created under the B.H.U. Act, 1915. The largest residential university in Asia and one of the largest in the world, having over 40,000 students across arts, commerce, sciences, engineering, linguistic, Ritual medical, agriculture, performing arts, law and technology from all over the world. He was Vice Chancellor of Banaras Hindu University from 1919–1938.

He is also remembered for his role in ending the Indian indenture system, especially in the Caribbean. His efforts in helping the Indo-Caribbeans is compared to Mahatma Gandhi's efforts of helping Indian South Africans.

Malaviya was one of the founders of

Scouting in India. He also founded a highly influential, English-newspaper, The Leader published from Prayagaraj in 1909. He was also the Chairman of Hindustan Times from 1924 to 1946. His efforts resulted in the launch of its Hindi edition named Hindustan Dainik in 1936.

He was posthumously conferred with Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, on 24 December 2014, a day before his 153rd Birth Anniversary.

-- Madan Mohan Malaviya, by Wikipedia

Sir Sunder Lal [5]...

Rai Bahadur Sir Sunder Lal CIE was born in Jaspur, near Nainital, on 21 May 1857.

In 1876, he joined Muir Central College at Allahabad then led by Augustus Harrison. While an under-graduate Pandit Sunder Lal passed the Vakil's Examination of the High Court in 1880 and was enrolled as a Vakil on 21 December 1880. He practiced in Allahabad High Court. In 1896 the High Court raised him to the rank and status of Advocate.

The distinction of 'Rai Bahadur' was conferred on him in 1905. He was

appointed a CIE in 1907. In 1909 he accepted a seat on the Bench of the Judicial Commissioner's Court at Lucknow for a few months and in 1914 for brief periods officiated as a Judge of the Allahabad High Court.

Appointed Member, Council of Law Reporting, Allahabad; Member of the Board of the Allahabad Court to represent Vakils, 1893; enrolled as Advocate, 1893; Fellow Allahabad University, since 1888 Member of the Syndicate, 1895, represented University in U.P. Legislative Council, 1904; and 1906–1909; one of the Secretaries of the MacDonnell Boarding House, Allahabad; Offg. Additional Judicial Commissioner, Oudh, 1909; Vice-Chairman, U.P. Exhibition, 1910–11; acting Judicial Commissioner for 5 months; Judge, High Court, N.W.P.. 1914; owner of the largest private library in the Province; prominently connected with the establishment of the University School of Law and the Hindu University, Benares; nominated as an Additional Member, Imperial Legislative Council, 1915: resigned his seat in the U.P. Legislative Council, 1915. Address: Allahabad.

In 1906, he became the first Indian Vice Chancellor of Allahabad University. He was reappointed to that office in 1912 and 1916.

In 1916, he was named the founding Vice Chancellor of Banaras Hindu University (BHU). The Sir Sunderlal Hospital of the Institute of Medical Sciences on the BHU campus is named in his honor.

On 21 February 1917, Sunder Lal received a knighthood. He died in Allahabad on 13 February 1918 at age 61.

-- Sunder Lal (lawyer), by Wikipedia

and

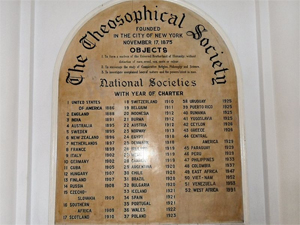

British Theosophist and Home Rule League founder Annie Besant.[6] With over 30,000 students residing in campus, it is the largest residential university in Asia.[7]

The university's main campus spread over 1,300 acres (5.3 km2) was built on land donated by the Kashi Naresh Prabhu Narayan Singh, the hereditary ruler of Banaras ("Kashi" being an alternative name for Banaras or Varanasi). The south campus, spread over 2,700 acres (11 km2),[8] hosts the Krishi Vigyan Kendra (Agriculture Science Centre)[9] and is located in Barkachha in Mirzapur district, about 60 km (37 mi) from Banaras.[10]

BHU is organised into six institutes and 14 faculties (streams) and about 140 departments.[11][12] As of 2017, the total student enrolment at the university is 27,359[13] coming from 48 countries.[14] It has over 75 hostels for resident students. Several of its faculties and institutes include arts (FA - BHU), commerce (Faculty of Commerce, Banaras Hindu University), management studies (Institute of Management Studies Banaras Hindu University|I.M.St. - BHU), science (I.Sc. - BHU), performing arts (FPA-BHU), law (FL-BHU), agricultural science (Institute of Agricultural Science, Banaras Hindu University|I.A.S. - BHU), medical science (Institute of Medical Science, Banaras Hindu University|I.M.S. - BHU) and environment and sustainable development (Institute of Environment And Sustainable Development, Banaras Hindu University|I.E.S.D. - BHU) along with departments of linguistics, journalism & mass communication, among others. The university's engineering institute was designated as an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT BHU) in June 2012.

BHU celebrated its centenary year in 2015–2016. The Centenary Year Celebration Cell organised various programs including cultural programs, feasts, competitions and Mahamana Madan Mohan Malviya Birth Anniversary on 25 December 2015.[15]

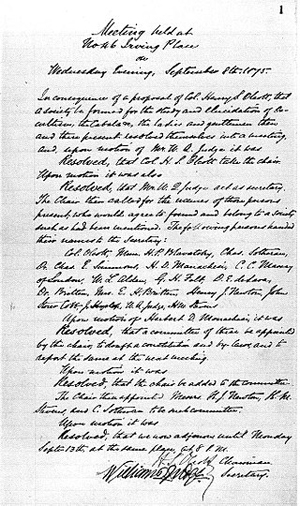

History Statue of Madan Mohan Malaviya at the entrance of Shri Vishwanath Mandir

Statue of Madan Mohan Malaviya at the entrance of Shri Vishwanath MandirThe Banaras Hindu University was established by Madan Mohan Malaviya. A prominent lawyer and an Indian independence activist, Malaviya considered education as the primary means for achieving a national awakening.[16]

At the 21st Conference of the Indian National Congress in Benares in December 1905, Malaviya publicly announced his intent to establish a university in Varanasi. Malaviya continued to develop his vision for the university with inputs from other Indian nationalists and educationists. He published his plan in 1911. The focus of his arguments was the prevailing poverty in India and the decline in income of Indians compared to Europeans. The plan called for the focus on technology and science, besides the study of India's religion and culture:

"The millions mired in poverty here can only get rid (of it) when science is used in their interest. Such maximum application of science is only possible when scientific knowledge is available to Indians in their own country."[17]

Malaviya's plan evaluated whether to seek government recognition for the university or operate without its control. He decided in favour of the former for various reasons. Malaviya also considered the question of medium of instruction and decided to start with English given the prevalent environment, and gradually add Hindi and other Indian languages. A distinguishing characteristic of Malaviya's vision was the preference for a residential university. All other Indian universities of the period, such as the universities in Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, etc., were affiliating universities which only conducted examinations and awarded degrees to students of their affiliated colleges.[18] Malaviya had supported Annie Besant's cause and in 1903, he had raised 250,000 Rupees in donations to finance the construction of the school's hostel.[19] In 1907 Besant had applied for a royal charter to establish a university. However, there was no response from the British government.

Following the publication of Malviya's plan, Besant met Malviya and in April 1911 they agreed to unite their forces to build the university in Varanasi.[20]

Malaviya soon left his legal practice to focus exclusively on developing the university and his independence activities.[21] On 22 November 1911, he registered the Hindu University Society to gather support and raise funds for building the university.[22] He spent the next 4 years gathering support and raising funds for the university. Malaviya sought and received early support from the Kashi Naresh Prabhu Narayan Singh and Maharaja Sir Rameshwar Singh Bahadur of Raj Darbhanga.[18] Thakur Jadunath Singh of Arkha along with other noble houses of United Provinces contributed for the development of the university.

In October 1915, with support from Malaviya's allies in the Indian National Congress, the Banaras Hindu University Bill was passed by the Imperial Legislative Council.[23]

BHU was finally established in 1916, the first university in India that was the result of a private individual's efforts. The foundation for the main campus of the university was laid by Lord Hardinge, the then Viceroy of India, on Vasant Panchami 4 February 1916.[20][24] To promote the university's expansion, Malviya invited eminent guest speakers such as Mahatma Gandhi, Jagadish Chandra Bose, C. V. Raman, Prafulla Chandra Roy, Sam Higginbottom, Patrick Geddes, and Besant to deliver a series of what are now called The University Extension Lectures between 5–8 February 1916. Gandhi's lecture on the occasion was his first public address in India.[24]

Sir Sunder Lal was appointed the first Vice-Chancellor, and the university began its academic session[6] the same month with classes initially held at the Central Hindu School in the Kamachha area, while the campus was being built on over 1,300 acres (5.3 km2) of land donated by the Kashi Naresh on the outskirts of the city. The Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar, Mir Osman Ali Khan, also made a donation of ₹1 lakh for the university.[25][26][27]

The university's anthem, known as the Kulgeet, was composed by Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar.[28]

Campus

Main campus Dept of Electrical Engineering IIT-BHU

Dept of Electrical Engineering IIT-BHU Sir Sundarlal Hospital

Sir Sundarlal Hospital Ruiya Medical Hostel, BHU

Ruiya Medical Hostel, BHUBHU is located on the southern edge of Varanasi, near the banks of the river Ganges. Development of the main campus, spread over 1,300 acres (5.3 km2), started in 1916 on land donated by the then Kashi Naresh Prabhu Narayan Singh. The campus layout approximates a semicircle, with intersecting roads laid out along the radii or in arcs. Buildings built in the first half of the 20th century are fine examples of Indo-Gothic architecture.

The campus has over 60 hostels offering residential accommodation for over 12,000 students.[29] On-campus housing is also available to a majority of the full-time faculty.

The main entrance gate and boundary wall was built on the donation made by Maharaja of Balrampur, Maharaja Pateshvari Prashad Singh.

The Sayaji Rao Gaekwad Library is the main library on campus and houses over 1.3 million volumes as of 2011. Completed in 1941, its construction was financed by Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda. In addition to the main library, there are three institute libraries, eight faculty libraries and over 25 departmental libraries available to students and staff.

Sir Sunderlal Hospital on the campus is a teaching hospital for the Institute of Medical Sciences. Established in 1926 with 96 beds, it has since been expanded to over 900 beds and is the largest tertiary referral hospital in the region.

Shri Vishwanath Mandir has the tallest temple tower in the world.[30]

Shri Vishwanath Mandir has the tallest temple tower in the world.[30]The most prominent landmark is the Shri Vishwanath Mandir, located in the centre of the campus. The foundation for this 252 feet (77 m) high complex of seven temples was laid in March 1931, and took almost three decades to complete.[31]

Bharat Kala Bhavan is an art and archaeological museum on the campus. Established in January 1920, its first chairman was Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, with his nephew Abanindranath Tagore as the vice-chairman. The museum was expanded and gained prominence with the efforts of Rai Krishnadasa.[32] The museum is best known for its collection of Indian paintings, but also includes archaeological artefacts, textiles and costumes, Indian philately as well as literary and archival materials.[33] The Alice Boner Gallery was also set up at Bharat Kala Bhavan with the assistance of the Alice Boner Foundation in 1989 to mark the birth centenary of Alice Boner.[34]

Rajiv Gandhi South CampusThe south campus is located in Barkachha in Mirzapur district,[8] about 60 km (37 mi) southwest of the main campus. Spread over an area of over 2,700 acres (11 km2), it was transferred as a lease in perpetuity to BHU by the Bharat Mandal Trust in 1979.[35]

It hosts the Krishi Vigyan Kendra (Agricultural Science Centre), with focus on research in agricultural techniques, agro-forestry and bio-diversity appropriate to the Vindhya Range region.[36] The South Campus features a lecture complex, library, student hostels and faculty housing, besides administrative offices.[37]

AcademicsBHU is organised into 6 institutes and 14 faculties (streams). The institutes are administratively autonomous, with their own budget, management and academic bodies.[38]

Institutes

Indian Institute of Technology (BHU) VaranasiMain article: Indian Institute of Technology, BHU

The Indian Institute of Technology (BHU) Varanasi (IIT-BHU) is an engineering institute under the aegis of BHU. IIT-BHU has 14 departments and 3 inter-disciplinary schools,[39] providing technology education with an emphasis on its industrial applications. Established in 1919, it is one of the oldest engineering institutes in India.[40] The institute in its present form was created by the merger of three BHU colleges – the Banaras Engineering College, the College of Mining and Metallurgy, and the College of Technology.

It was designated as Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) by The Institutes of Technology (Amendment) Act, 2012[41] of Parliament in 2012[42] and is declared as Institute of National Importance by Government of India under IIT Act.[43]

Institute of ScienceMain article: Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University

The Institute of Science (ISc) comprises 13 departments covering various branches of modern science, and several inter-disciplinary schools and research centres. It offers Undergraduate (B.Sc), Post graduate (M.Sc) and Ph.D in most disciplines, MSc (Tech.) in Geophysics, MCA, and conducts research programmes in all areas.Two vocational courses, Industrial Microbiology and Electronics Instrumentation and Maintenance have been introduced in recent years at U.G. level. Aakanksha is its annual cultural fest organised every year in the month of February.[44]

Institute of Agricultural SciencesMain article: Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University

The Institute of Agricultural Sciences (IAS) was founded as Institute of Agricultural Research in 1931 and was the first institute in India to provide postgraduate programs (MSc and PhD) in agricultural science. In 1945, undergraduate degrees were introduced and it was renamed as the College of Agriculture. It was renamed as the Faculty of Agriculture in 1968 and was raised to the status of the Institute of Agricultural Sciences in August 1980. It is involved in both education and research in agricultural science.[45]

Institute of Medical Sciences Institute of Medical Sciences, BHU

Institute of Medical Sciences, BHUMain article: Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University

The Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS) is a residential, co-educational medical institute. It admits students for its programs in medicine through the NEET entrance examination held across India. In addition to the MBBS programs, it offers specialisations and PhD programs for physicians in medicine and surgery. It also offers graduate and post-graduate programs in Nursing, Ayurvedic medicine, Dentistry and Health Statistics. It is one of the finest institutes in the country. It produces some of the best physicians and results across the country. There are three faculties viz. Medicine, Ayurveda and Dental Sciences.

Institute of Environment and Sustainable DevelopmentThe Institute of Environment & Sustainable Development (IESD) aiming to develop and advance the knowledge of technology and processes for sustainable development was started in 2010 in the tenure of the then Vice-Chancellor of BHU, D.P. Singh.[46]

In accordance with the UN visualisation that higher education should contribute significantly to the development of appropriate knowledge and competencies in the area of sustainable development, a nation-level Institute of Environment & Sustainable Development has been established in the Banaras Hindu University. The institute will cover education about sustainable development (developing an awareness of what is involved) and education for sustainable development (using education as a tool to achieve sustainability). The institute will be dedicated to a better understanding of critical scientific and social issues related to sustainable development goals through guided research.[47]

Institute of Management StudiesThe Institute of Management Studies is the business school of Banaras Hindu University. Established in 1968 as the Faculty of Management Studies (FMS, BHU), it is among the earliest management schools in India. It was renamed to its current name on 16 December 2015.[48]

The institute offers several two-year Master of Business Administration (MBA) programmes. Admission is based on the combined merit acquired by a candidate in CAT, group discussion and interview. Eligibility requirements are a graduate degree under 10+2+3 Pattern / degree in Agriculture, Technology, Medicine, Education or Law / Post-graduate degree in any discipline under 10+2+3+2 pattern from any Indian University/Institution recognised by AIU/AICTE with at least 50% marks in aggregate (at least 45% for SC/ST candidates).[49]

Faculties Faculty of Arts, Banaras Hindu University

Faculty of Arts, Banaras Hindu UniversityAcademic faculties of the university include:[50]

• Faculty of Arts

• Faculty of Ayurveda

• Faculty of Commerce

• Faculty of Education

• Faculty of Law

• Faculty of Performing Arts

• Sanskrit Vidya Dharma Vijnan Sankaya

• Faculty of Social Sciences

• Faculty of Visual Arts

Faculty of Performing ArtsThe Faculty of Performing Arts offers undergraduate, postgraduate and doctorate courses in performing arts. It was founded in 1950 and had several renowned and award-winning artists and musicians as faculty members.[51][52] Faculty of Performing Arts was started by Omkarnath Thakur in 1950. It was initially instituted as a college called "Music and Fine Arts". In 1966, under Govind Malviya and founding principal Omkarnath Thakur, the college was restructured to a faculty, with three departments (Vocal music, Instrumental music and Musicology). Faculty of Performing Arts claims to start the first department of Musicology in India headed by musicologists Prem Lata Sharma.[51]

Faculty of Social Sciences Samanvaya Bhawan, Faculty of Social Sciences (Old PG Building) as seen from Faculty of Arts building

Samanvaya Bhawan, Faculty of Social Sciences (Old PG Building) as seen from Faculty of Arts buildingThe Faculty of Social Sciences offers undergraduate and postgraduate courses in Social science. It was bifurcated from the Faculty of Arts in 1971. It includes the departments of Economics, History, Political Science, Psychology and Sociology.[53]

Other than the departments, there are five centres which carry on the studies in various fields, namely the Centre for the Study of Nepal, Centre for Women's Study and Development, Centre for Integrated Rural Development, Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusion Policy and the Malviya Centre for Peace Research.[54]

The faculty holds three chairs, the currently (as of 2018) vacant Babu Jagjivan Ram Chair for Social Research, commemorating Jagjivan Ram and his contributions,[55] the Dr. Ambedkar Chair for Nationalism & National Integration established in 2016[56] and the Pt. Deendayal Upadhyay Chair, established in 2017.[57]

Currently, Koushal Kishor Mishra is the Dean of Faculty of Social Sciences. This faculty also has several professors at administrative positions likewise Professor Sanjay Srivastava as the Member of BHU Court and Professor Ram Pravesh Pathak (Former Dean) as Chairman of Student Grievance Cell.

Faculty of Visual ArtsThe Faculty of Visual Arts offers undergraduate and postgraduate courses in applied and visual arts. It was founded in 1916.[58] It includes five departments:

• Painting

• Applied arts

• Plastic arts

• Pottery and Ceramics

• Textile designing

Inter-disciplinary schools

School of Biotechnology School of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Banaras Hindu University

School of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Banaras Hindu UniversityThe School of Biotechnology (SBT) is a center for postgraduate teaching and research under the aegis of Institute of Science of the BHU.[59][60] It was established in 1986 with funding from the Department of Biotechnology,[61] of the Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India. It offers MSc and PhD programmes in Biotechnology.

The interdisciplinary program involves the partnership between the Institute of Science, the Institute of Medical Sciences and the Indian Institute of Technology at BHU. Notable faculty include Arvind Mohan Kayastha.[62]

DBT-BHU Interdisciplinary School of Life SciencesThe Interdisciplinary School of Life Sciences (ISLS) is a joint initiative of the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India and the BHU. It was established with a grant of INR 238.9 million from the DBT.[63]

DST Centre for Interdisciplinary Mathematical SciencesThe Centre for Interdisciplinary Mathematical Sciences (CIMS) focuses on research and education in mathematics, modelling and statistics. It was established under the management of the Faculty of Science, with support from the Department of Science and Technology (DST).[64] The centre imparts post-graduate education and research with participation from the Department of Mathematics, Department of Statistics and Department of Computer Science of the Institute of Science and the Department of Applied Mathematics of the IIT-BHU. It regularly organises training programmes, workshops, Seminars and conferences.

Centre of Food Science and TechnologyThe Centre of Food Science & Technology (CFST) is an inter-disciplinary research centre with collaboration between the Institute of Agricultural Sciences and the Indian Institute of Technology (BHU) focusing on food processing technology.[65]

Research centresApart from specialised centres directly funded by DBT, DST, ICAR and ISRO, a large number of departments under the Institutes of Sciences, Engineering & Technology and Faculty of Social Sciences receive funding from the DST Fund for Improvement of Science & Technology Infrastructure (FIST) and the University Grants Commission (UGC) Special Assistance Programme (SAP). UGC SAP provides funds under its Centre of Advanced Study (CAS), Department of Special Assistance (DSA) and Departmental Research Support (DRS) programmes.[66]

BHU research centres include:

• DBT Centre of Genetic Disorders[67]

• Center for Environmental Science and Technology[68]

• Nano science and Technology Center

• Hydrogen Energy Center

• UGC Advanced Immunodiagnostic Training and Research Center

• Centre for Experimental Medicine and Surgery

• Center for Women's Studies and Development (CWSD)[69]

• Center for the Study of Nepal (CNS)[70]

• Malviya Center for Peace Research (MCPR)[71]

• Center for Rural Integrated Development (CIRD)[72]

• Centre for Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy (CSSEIP)[73]

• DST Centre for Interdisciplinary Mathematical Sciences

Affiliated colleges and schools

Colleges• Arya Mahila Mahavidyalaya

• DAV Post Graduate College

• Vasanta College for Women

• Vasant Kanya Mahavidyalaya

Schools• Ranvir Sanskrit Vidyalaya,[74]

• Central Hindu Boys School[75]

• Central Hindu Girls School[76]

Library systemMain article: Sayaji Rao Gaekwad Library, BHU

Central Library, BHU

Central Library, BHUThe Banaras Hindu University Library system was established from a collection donated by P.K. Telang in the memory of his father Justice Kashinath Trimbak Telang in 1917. The collection was housed in the Telang Hall of the Central Hindu College, Kamachha. In 1921, the library was moved to the Central Hall of the Arts College (now the Faculty of Arts).

The present Central Library of BHU was established with a donation from Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda. Upon his return from the First round Table Conference, Gaekwad wanted a library built on the pattern of the British Library and its reading room, which was then located in the British Museum. On Malviya's suggestion, he made the donation to build the library on the BHU campus.[77]

The Gaekwad Library is a designated Manuscript Conservation Centre (MCC) of the National Mission for Manuscripts,[78] established in 2003.[79]

By 1931, the library had built a collection of around 60,000 volumes. The trend of donation of personal and family collection to the library continued as late as the 1940s with the result that it has unique pieces of rarities of books and journals dating back to the 18th century.

As of 2011, the BHU Library System consisted of the Central Library and 3 Institute Libraries, 8 Faculty Libraries and over 25 Departmental Libraries, with a collection of at least 1.3 million volumes.[77] The digital library is available to students and staff and provides online access to thousands of journals, besides access to large collections of online resources[80] through the National Informatics Centre's DELNET[81] and UGC's INFLIBNET.[82]

ProtestsMain article: Banaras Hindu University women's rights protest

On 21 September 2017 a woman reported sexual harassment to the university. She claimed that the university responded by blaming her.[83] The next day, 22 September, students organised a protest of the university's treatment of women.

The university's administration filed a First information report against hundreds of students. Security officers used violence in an attempt to get protesters to disperse. Various protesters reported injuries.[84]

AdmissionsBanaras Hindu University conducts national level undergraduate (UET) and postgraduate (PET) entrance tests usually during May–June for admission for which registrations begin usually in February–March.[85] Admissions are done according to merit in the entrance tests, subject to fulfilling of other eligibility requirements. Admissions to BTech/B.Pharm., MTech/M.Pharm. are done through JEE and GATE respectively. Admission to MBA and MBA-IB are done through IIM-CAT score and also through separate BHU-MBA entrance tests. Admissions for PhD are done on the basis of either qualification of National Eligibility Test (NET) by the candidates or through the scores of CRET (Common Research Entrance Test). Admissions in IMS are done through PMT exam.

BHU attracts a number of foreign learners. Foreign students are admitted through the application submitted to the Indian mission in his/her country or by his/her country's mission in India.

BHU conducts UG entrance exam every year in May. The offline exam is held for 5166 seats. The total exam duration is two hours with 150 MCQs and the total marks is 450. There are seven participating colleges including BHU Faculty of Law and six constituent colleges.[86]

Halls of residenceBHU is a fully residential University with a total of 62 hostels - 41 hostels for male and 21 hostels for female students.

There are four separate hostels for international students. These four include an International House Annexe for female students with an intake capacity of 24. Hostels are named after several historically important figures such as Raja Baldev Das Jugal Kishore Birla, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Rani Laxmibai and M. Visvesvaraya.

Birla Hostel 'A'The faculty has one of the oldest hostels in the University named Birla Hostel constructed in 1921 by the industrialist Shri Jugal Kishore Birla in the memory of his father Raja Baldev Das Birla. It is a large hostel and for administrative purposes it was divided into three sub-hostels - Birla A, Birla B and Birla C; about a decade back[when?]. Undergraduate students are accommodated in Birla A while Birla B is meant for Research Scholars and Birla C for Postgraduate students.[citation needed]

FestivalsBHU observes Saraswati puja day (also known as Vasant Panchami) as its foundation day. Goddess Saraswati is the Hindu goddess of knowledge, music, arts, wisdom and nature. She is a part of the trinity of Saraswati, Lakshmi and Parvati.

There is also an intra-university fest 'Spandan', where students represent their faculty/institute in various arts competition like literature (writing essay, poem, debates), painting, sketches, vocal music, dancing, singing, drama, and mimicry. It is held every year after Vasant Panchami in month of February or March.

RankingsInternationally, BHU was ranked 801–1000 in the QS World University Rankings of 2020.[87] The same rankings ranked it 177 in Asia in 2020[88] and 90 among BRICS nations in 2019.[89] It was ranked 601–800 in the world by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings of 2020[90] and 167 in Asia in 2020.[91]

In India, the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) ranked it tenth overall in 2020[93] and third among universities.[94] It also ranked it 36 in the management ranking.[104]

Its engineering institute, IIT, was ranked 11 by the NIRF Engineering ranking for 2019.[97] In 2019, it was ranked 9th among engineering colleges in India by The Week.[98]

The Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University was ranked 5th in India by Outlook India's "India's Top 30 Law Colleges In 2019"[103] and seventh in India by The Week's "Top Law Colleges 2019".[102]

The Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University was ranked seventh among medical colleges in India in 2020 by India Today,[101] sixth by The Week[100] and eight by Outlook India.[99]

Awards and medalsThe following awards and medals are given to meritorious students in BHU:

BHU Medal is given to students who secure the first position in their respective departments or faculties.Notable alumni, faculty and staff

BHU Medal is given to students who secure the first position in their respective departments or faculties.Notable alumni, faculty and staffMain articles: List of Banaras Hindu University people and List of Vice-Chancellors of Banaras Hindu University

Alumni and faculty of BHU have gained prominence in India and across the world. Among BHU's administrators was Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who went on to become the President of India. Other famous administrators include Sir Sunder Lal, K. L. Shrimali, Moti Lal Dhar.

The university's alumni include Raj Narain, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay, C.N.R Rao, Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Bhupen Hazarika, Shyam Sunder Surolia, Veena Pandey, A. K. Narain, Kamalesh Chandra Chakrabarty, Ashok Agarwal, Jagdish Kashyap, T. V. Ramakrishnan, Harkishan Singh, Narla Tata Rao, Patcha Ramachandra Rao, Jayant Vishnu Narlikar, Basanti Dulal Nagchaudhuri, Ahmad Hasan Dani, Kota Harinarayana, Kothapalli Jayashankar, Krishan Kant, Manick Sorcar, Satish K. Tripathi, Shashi P. Karna, Tapan Singhel, Raja Ram Jain and Prem Saran Satsangi. Amongst its famous international students are Robert M. Pirsig and Koenraad Elst.

BHU's faculty have included Ganesh Prasad, Birbal Sahni, Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar, Prafulla Kumar Jena,[105] Omkarnath Thakur, N. Rajam and A. K. Narain.

See also· Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith

· Aligarh Muslim University

· Siddharth University

References1. "Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi". www.bhu.ac.in. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

2. "Vice-Chancellor". www.bhu.ac.in. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

3. "University". www.ugc.ac.in. Retrieved 10 February2020.

4. Jha, Dhirendra K. "Malviya was not the main founder of Banaras Hindu University, researcher claims". Scroll.in. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

5. Jha, Tejakar (7 August 2015). The Inception of Banaras Hindu University: Who Was the Founder in the Light of Historical Documents?. ISBN 9781482852479.

6. "History of BHU". Banaras Hindu University website. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

7. "University at Buffalo, BHU sign exchange programme". Rediff News. 4 October 2007.

8. "About the Campus". Krishi Vigyan Kendra, BHU. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 3 June2012.

9. "Rajiv Gandhi South Campus". Krishi Vigyan Kendra, BHU. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

10. "Banaras Hindu University keen to setup its Center in Bihar". IANS. Biharprabha News. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

11. "UGC BHU Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 11 December 2018.

12. "UGC Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018.

13. "Submitted Institute Data for National Institute Ranking Framework - Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi" (PDF). NIRF. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

14. "Banaras Hindu University: All rounder : 2011 - India Today". indiatoday.intoday.in. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

15. "10 things to know about Madan Mohan Malviya". ABP Live. 24 December 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

16. "Founder of Banaras Hindu University: Mahamana Bharat Ratna Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya" (PDF). Banarash Hindu University. 2006. p. 18. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

17. "Founder of Banaras Hindu University: Mahamana Bharat Ratna Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya" (PDF). Banarash Hindu University. 2006. p. 19. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

18. Singh, Rana P.B.; Pravin S. Rana (2002). Banaras Region: A Spiritual and Cultural Guide. Varanasi: Indica Books. p. 141. ISBN 81-86569-24-3.

19. "Founder of Banaras Hindu University: Mahamana Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya" (PDF). Banarash Hindu University. 2006. p. 12. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

20. "Bharat Ratna Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya: The Man, The Spirit, The Vision". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 3 June2012.

21. "Founder of Banaras Hindu University: Mahamana Bharat Ratna Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya" (PDF). Banarash Hindu University. 2006. p. 11. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

22. "Founder of Banaras Hindu University: Mahamana Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya" (PDF). Banarash Hindu University. 2006. p. 30. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

23. "The Banaras Hindu University Act, 1915". Indian Kanoon. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

24. "Madan Mohan Malaviya and Banaras Hindu University"(PDF). Current Science. Indian Academy of Sciences. 101 (8). 25 October 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

25. "A 'miser' who donated generously". The Hindu. 24 May 2013.

26. Ifthekhar, AuthorJS. "Reminiscing the seventh Nizam's enormous contribution to education". Telangana Today.

27. "Nizam gave funding for temples, and Hindu educational institutions". 28 May 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

28. "Heritage Complex". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

29. "Student Amenities". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

30. "Brief description". Benaras Hindu University website. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 7 March2015.

31. "Landmarks and Heritage of BHU". Banaras Hindu University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 4 June2012.

32. "History". Bharat Kala Bhavan. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

33. "Collection". Bharat Kala Bhavan. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

34. "Alice Boner Gallery". Archived from the original on 17 August 2018.

35. "History". RGSC, Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

36. "Research Projects". Krishi Vigyan Kendra, BHU. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

37. "Infrastructure". Krishi Vigyan Kendra, BHU. Retrieved 4 June2012.

38. [1]

39. "Departments".

40. "Introduction". IIT Kanpur. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

41. "IIT-BHU Act" (PDF).

42. Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department) (21 June 2012). "IT-Amendment-Act-2012" (PDF). The Gazette of India. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

43. "Institutions of National Importance". Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. Retrieved 25 June2015.

44. "Amar Ujala".

45. "Introduction". Institute of Agricultural Sciences, BHU. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

46. "Welcome". Institute of Environment & Sustainable Development, BHU. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

47. "IESD". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018.

48. http://www.bhu.ac.in/fms/NofIoMS-BHU16Dec2015.pdf

49. "Welcome to Institute of Management Studies, BHU". www.bhu.ac.in. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

50. "Faculty & Institute, BHU". Bhu.ac.in. 19 August 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

51. "Faculty of Performing Arts". BHU website. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

52. "Location". Latlong.net. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

53. "Welcome to "Faculty of Social Sciences"". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

54. "Welcome to "Faculty of Social Sciences"". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 8 February 2018. Click "Centers".

55. "Babu Jagjivan Ram Chair for Social Research (BJRC)". bhu.ac.in. Banaras Hindu University, Faculty of Social Sciences Varanasi. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

56. "The Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Chair". bhu.ac.in. Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

57. "Pt. Deendayal Upadhyay Chair". bhu.ac.in. Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

58. "About Faculty of Visual Arts". BHU website. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

59. "Home Page of Faculty of Science, BHU". Archived from the original on 2 April 2009.

60. "About the department - School of Biotechnology, BHU". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 4 June2012.

61. "Human Resource Development, Department of Biotechnology, Government of India". Archived from the original on 24 November 2011.

62. "Lab web page of Prof. A. M. Kayastha, School of Biotechnology". Retrieved 10 February 2020.

63. "Central grant to BHU for school of life sciences". The Times of India. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

64. "About us". DST Centre for Interdisciplinary Mathematical Sciences, BHU. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

65. "Overview". Centre of Food Science & Technology, BHU. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

66. "Financial Support: Special Assistance Programme (SAP)". University Grants Commission. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

67. "About CGD". Centre for Genetic Disorders, BHU. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

68. "Welcome". Centre for Environmental Science & Technology, BHU. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

69. "CWSD". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018.

70. "CSN".[dead link]

71. "MCPR". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018.

72. "CIRD". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018.

73. "CSSEIP". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018.

74. "RSV". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018.

75. "CHS". Archived from the original on 21 July 2018.

76. "CHGS". Archived from the original on 21 July 2018.

77. "Genesis and history". Sayaji Rao Gaekwad Library, BHU. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June2012.

78. "Manuscript Conservation Centres". National Mission for Manuscripts. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

79. "History". National Mission for Manuscripts. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

80. "Library Services". Banaras Hindu University. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

81. "Developing Library Network". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 6 June2012.

82. "Information and Library Network Centre". University Grants Commission. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

83. Mishra, Bishnu (2 October 2017). "Student Protests Have Challenged the Ideological Stagnation of BHU". The Wire (Indian web publication).

84. "What is the BHU protest? everything you need to know". The Indian Express. 25 September 2017.

85. "Application process" (PDF).

86. "BHU UET 2019 – Check Results, Cut Off, Scorecard, Merit List, Counselling". university.careers360.com.

87. "QS World University Rankings 2020". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

88. "QS Asia University Rankings 2020". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020.

89. "QS BRICS University Rankings 2019". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2018.

90. "Top 1000 World University Rankings 2020". Times Higher Education. 2019.

91. "Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings (2020)". Times Higher Education. 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

92. "Times Higher Education Emerging Economies University Rankings (2020)". Times Higher Education. 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

93. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2020 (Overall)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 11 June 2020.

94. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2020 (Universities)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 11 June 2020.

95. "The Week India University Rankings 2019". The Week. 18 May 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

96. "Outlook India University Rankings 2019". The Outlook. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

97. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2019 (Engineering)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 2018.

98. Pushkarna, Vijaya (8 June 2019). "Best colleges: THE WEEK-Hansa Research Survey 2019". The Week.

99. "Outlook Ranking: India's Top 25 Medical Colleges In 2019 Outlook India Magazine". Retrieved 22 January 2020.

100. Pushkarna, Vijaya (8 June 2019). "Best colleges: THE WEEK-Hansa Research Survey 2019". The Week.

101. "Best MEDICAL Colleges 2020: List of Top MEDICAL Colleges 2020 in India". www.indiatoday.in. Retrieved 13 July2020.

102. Pushkarna, Vijaya (8 June 2019). "Best colleges: THE WEEK-Hansa Research Survey 2019". The Week.

103. "Outlook India: India's Top 30 Law Colleges In 2019 Outlook India Magazine". Retrieved 22 January 2020.

104. "National Institutional Ranking Framework 2020 (Management)". National Institutional Ranking Framework. Ministry of Education. 11 June 2020.

105. "Institute of Advanced Technology and Environmental Studies profile" (PDF). Institute of Advanced Technology and Environmental Studies. 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

Further reading· Leah Renold, A Hindu Education: Early Years of the Banaras Hindu University (Oxford University Press).

External links· Official website