by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/1/20

Jugantar or Yugantar (Bengali: যুগান্তর Jugantor) (English meaning New Era or more literally Transition of an Epoch) was one of the two main secret revolutionary trends operating in Bengal for Indian independence. This association, like Anushilan Samiti started in the guise of suburban fitness club. Several Jugantar members were arrested, hanged, or deported for life to the Cellular Jail in Andaman. Thanks to the amnesty after World War I, most of them were released and could give a new turn to their political career, mainly: (a) by joining Deshbandhu's Swarajya ...

The Swaraj Party was established as the Congress-Khilafat Swaraj Party. It was a political party formed in India in January 1923 after the Gaya annual conference in December 1922 of the National Congress, that sought greater self-government and political freedom for the Indian people from the British Raj.

It was inspired by the concept of Swaraj. In Hindi and many other languages of India, swaraj means "independence" or "self-rule." The two most important leaders were Chittaranjan Das, who was its president and Motilal Nehru, who was its secretary.

Das and Nehru thought of contesting elections to enter the legislative council with a view to obstructing a foreign government. Many candidates of the Swaraj Party got elected to the central legislative assembly and provincial legislative council in the 1923 elections. In these legislatures, they strongly opposed the unjust government policies.[1]

As a result of the Bengal Partition, the Swaraj Party won the most seats during elections to the Bengal Legislative Council in 1923. The party disintegrated after the death of C. R. Das.[2]

-- Swaraj Party, by Wikipedia

or (b) the Communist Party of India; or (c) M. N. Roy's Radical Democratic Party; ...

Radical Democratic Party (RDP), was a political party in India which existed at the time of the Second World War. RDP evolved out of the League of Radical Congressmen, which had been founded in 1939 by former Communist International leader M.N. Roy. Roy founded Radical Democratic Party in 1940 with the purpose of engaging India in the war to support the Allies. RDP also worked for Indian independence. RDP was against the industrial strike that took place at the time.

During the period 1944-1948 the general secretary of RDP was V. M. Tarkunde.

The trade union wing of the Royists was the Indian Federation of Labour.

RDP was dissolved in 1948, to give place to the Radical Humanist movement.

-- Radical Democratic Party (India), by Wikipedia

or (d) later Subhas Chandra Bose's Forward Bloc in the 1930s.

The All India Forward Bloc (AIFB) is a left-wing nationalist political party in India. It emerged as a faction within the Indian National Congress in 1939, led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The party re-established as an independent political party after the independence of India. It has its main stronghold in West Bengal. The party's current Secretary-General is Debabrata Biswas. Veteran Indian politicians Sarat Chandra Bose (brother of Subhas Chandra Bose) and Chitta Basu had been the stalwarts of the party in independent India.

The Forward Bloc of the Indian National Congress was formed on May 3, 1939 by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, who had resigned from the presidency of the Indian National Congress on 29 April after being outmanoeuvered by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The formation of the Forward Bloc was announced to the public at a rally in Calcutta. Bose said that who all were joining, they had to never turn their back to the British and must fill the pledge form by cutting their finger and signing it with their blood. First of all, seventeen young girls came up and signed the pledge form. Initially the aim of the Forward Bloc was to rally all the leftwing sections within the Congress and develop an alternative leadership inside the Congress. Bose became the president of the Forward Bloc and S.S. Cavesheer its vice-president. A Forward Bloc Conference was held in Bombay in the end of June. At that conference the constitution and programme of the Forward Bloc were approved.[6] In July 1939 Subhas Chandra Bose announced the Committee of the Forward Bloc. It had Subhas Chandra Bose as president, S.S. Kavishar from Punjab as its vice-president, Lal Shankarlal from Delhi, as its general secretary and Pandit B Tripathi and Khurshed Nariman from Bombay as secretaries. Other prominent members were Annapurniah from Andhra Pradesh, Senapati Bapat, Hari Vishnu Kamnath from Bombay, Pasumpon U. Muthuramalingam Thevar from Tamil Nadu and Sheel Bhadra Yagee from Bihar. Satya Ranjan Bakshi, was appointed as the secretary of the Bengal Provincial Forward Bloc.[7]

In August, the same year Bose began publishing a newspaper titled Forward Bloc. He travelled around the country, rallying support for his new political project.[7]

The next year, on 20–22 June 1940, the Forward Bloc held its first All India Conference in Nagpur. The conference declared the Forward Bloc to be a socialist political party, and the date of 22 June is considered as the founding date of the party by the Forward Bloc itself. The conference passed a resolution titled 'All Power to the Indian People', urging militant action for struggle against British colonial rule. Subhash Chandra Bose was elected as the president of the party and H.V. Kamath as the general secretary.[8]

Soon thereafter, on 2 July, Bose was arrested and detained in Presidency Jail, Calcutta. In January 1941 he escaped from house arrest, and clandestinely went into exile. He travelled to the Soviet Union via Afghanistan, seeking Soviet support for the Indian independence struggle. Stalin declined Bose's request, and he then travelled to Germany. In Berlin he set up the Free India Centre, and rallied the Indian Legion.[9]

Inside India, local activists of the Forward Bloc continued the anti-British activities without central co-ordination. For example, in Bihar members were involved in the Azad Dasta resistance groups, and distributed propaganda in support of Bose and Indian National Army. They did not have, however, any organic link either with Bose nor the INA.[10]

At the end of the war, the Forward Bloc was reorganised. In February 1946 R.S. Ruiker organised an All India Active Workers Conference at Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. The conference declared the formation of the 'FB Workers Assembly', in practice the legal cover of the still illegal Forward Bloc. Notably some leading communists from Bombay, like K.N. Joglekar and Soli Batliwalli, joined the 'FB Workers Assembly'. The Workers Assembly conference declared that the "Forward Bloc is a Socialist Party, accepting the theory of class struggle in its fullest implications and a programme of revolutionary mass action for the attainment of Socialism leading to a Classless Society."[11]

-- All India Forward Bloc, by Wikipedia

Notable members

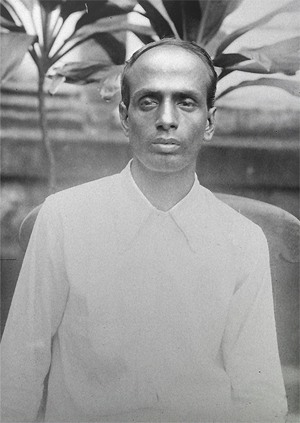

• Surya Sen (Masterda)

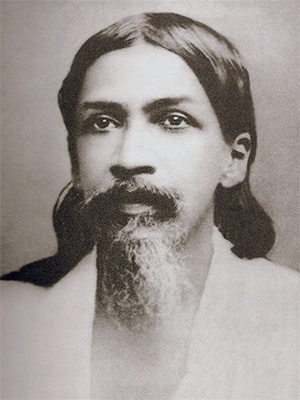

• Aurobindo Ghosh (1872-1950)

• Barin Ghosh

• Santi Ghose (1916-1989)

• Mohit Moitra

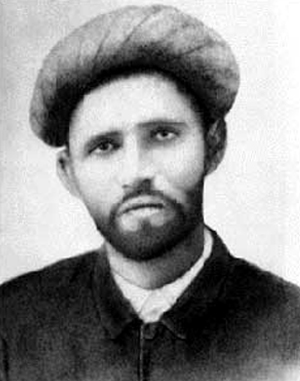

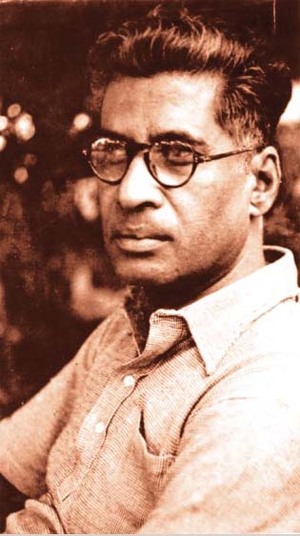

Bagha Jatin

• Bagha Jatin alias Jatindra Nath Mukherjee (1879-1915)

• Satyendra Chandra Mitra (1888-1942)

• Raja Subodh Mallik

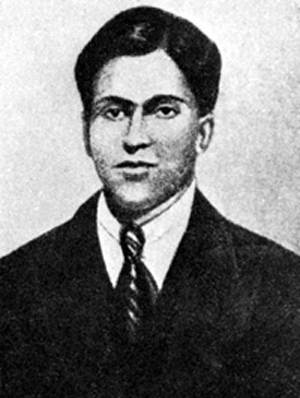

• Khudiram Bose

• Prafulla Chaki

Pritilata Waddedar

• Pritilata Waddedar (1911-1932)

• Kanailal Dutta (1888-1908)

• Satyendranath Bose (1882-1908)

• Santosh Kumar Mitra (1901-1931)

• Dinesh Chandra Majumdar (1907-1934)

• Ganesh Ghosh (b. 1900 )

• Jadugopal Mukherjee (1866-1976)

• Roshomoy Majumdar (d.1996)

• Manoranjan Gupta (b. 1890)

• Abinash Chandra Bhattacharya (1882 - 1962)

• Amarendra Chatterjee (1880-1957)

• Ambika Chakrobarty (1891-1962)

• Arun Chandra Guha (b. 1892)

• Basanta Kumar Biswas (1895-1915)

• Bipin Behari Ganguli (1887-1954)

• Bhupendra Kumar Datta (1894-1979)

• Jiban Lal Chattopadhyay (1889-1970)

• Jyotish Chandra Ghose (1887-1970)

• Taraknath Das (1884-1958)

• Tarakeswar Dastidar

• Purna Chandra Das (1889-1956)

• Surendra Mohan Ghosh alias Madhu Ghosh(1893-1976)

• Prabodh Kumar Ray (1908-1996) in Andaman till 1938,Tamrapatra conferred 1972

• Upendra Nath Bandopadhyay (1879-1950)

• Ullaskar Dutta

• Phanibhusan Bakshi

• Debabrata Bose, later Swami Paragyananda

• Chattalesh Chaudhuri (1913-1987)[1]

• Ishwar Shukla, later Jayadutta Shastree (1892-1966)

The beginning

The jugantar party was established by leaders like Aurobindo Ghosh, his brother Barin Ghosh, Bhupendranath Datta, Raja Subodh Mallik in April 1906.[2] Barin Ghosh and Bagha Jatin were the main leaders. Along with 21 revolutionaries, they started to collect arms, explosives and manufactured bombs.

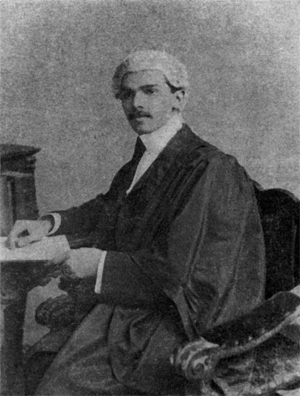

Barindra Kumar Ghosh or Barindra Ghosh, or, popularly, Barin Ghosh (5 January 1880 – 18 April 1959) was an Indian revolutionary and journalist. He was one of the founding members of Jugantar, a revolutionary outfit in Bengal. Barindra Ghosh was a younger brother of Sri Aurobindo.

-- Barindra Kumar Ghosh, by Wikipedia

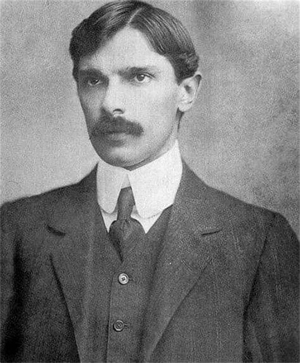

Bagha Jatin [Jatindranath Mukherjee](Bagha Jatin, lit: Tiger Jatin), born Jatindranath Mukherjee (Jotindrônāth Mukhōpaddhāē; 7 December 1879 – 10 September 1915), was an Indian freedom fighter.[1][2]

He was the principal leader of the Jugantar party that was the central association of revolutionary freedom fighters in Bengal.[1]...

After passing the Entrance examination in 1895 from Krishnanagar Anglo-vernacular School (A.V. School), Jatin joined the Calcutta Central College (now Khudiram Bose College), to study Fine Arts. At the same time, he took lessons in steno typing with Mr. Atkinson: this is a new qualification opening possibilities of a coveted career. Soon he started visiting Swami Vivekananda, whose social thought, and especially his vision of a politically independent India – indispensable for the spiritual progress of humanity – had a great influence on Jatin. The Master taught him the art of conquering libido before raising a batch of young volunteers "with iron muscles and nerves of steel", to serve miserable compatriots during famines, epidemics and floods and running clubs for "man-making" in the context of a nation under foreign domination. They soon assisted Sister Nivedita, the Swami's Irish disciple, in this venture. According to J. E. Armstrong, Superintendent of the colonial Police, Jatin "owed his preeminent position in revolutionary circles, not only to his qualities of leadership, but in great measure to his reputation of being a Brahmachari with no thought beyond the revolutionary cause."[5] Noticing his ardent desire to die for a cause, Swami Vivekananda sent Jatin to the Gymnasium of Ambu Guha where he himself had practised wrestling. Jatin met here, among others, Sachin Banerjee, son of Yogendra Vidyabhushan (a popular author of biographies like Mazzini and Garibaldi), who turned into Jatin's mentor. In 1900, his uncle Lalit Kumar married Vidyabhushan's daughter....

Several sources mention Jatin as being among the founders of the Anushilan Samiti in 1900, and as a pioneer in creating its branches in the districts.Anushilan Samiti (Ônushīlôn sômiti, lit: bodybuilding society) was a Bengali Indian organisation in the first quarter of the 20th century that supported revolutionary violence as the means for ending British rule in India. The organisation arose from a conglomeration of local youth groups and gyms (akhara) in Bengal in 1902. It had two prominent, somewhat independent, arms in East and West Bengal, Dhaka Anushilan Samiti (centred in Dhaka, modern day Bangladesh), and the Jugantar group (centred at Calcutta).

From its foundation to its dissolution during the 1930s, the Samiti challenged British rule in India by engaging in militant nationalism, including bombings, assassinations, and politically-motivated violence. The Samiti collaborated with other revolutionary organisations in India and abroad. It was led by the nationalists Aurobindo Ghosh and his brother Barindra Ghosh, and influenced by philosophies as diverse as Hindu Shakta philosophy, as set forth by Bengali authors Bankim and Vivekananda, Italian Nationalism, and the Pan-Asianism of Kakuzo Okakura. The Samiti was involved in a number of noted incidents of revolutionary attacks against British interests and administration in India, including early attempts to assassinate British Raj officials. These were followed by the 1912 attempt on the life of the Viceroy of India, and the Seditious conspiracy during World War I, led by Rash Behari Bose and Jatindranath Mukherjee [Bagha Jatin] respectively.

The organisation moved away from its philosophy of violence in the 1920s due to the influence of the Indian National Congress and the Gandhian non-violent movement. A section of the group, notably those associated with Sachindranath Sanyal, remained active in the revolutionary movement, founding the Hindustan Republican Association in north India. A number of Congress leaders from Bengal, especially Subhash Chandra Bose, were accused by the British Government of having links with the organisation during this time.

The Samiti's violent and radical philosophy revived in the 1930s, when it was involved in the Kakori conspiracy, the Chittagong armoury raid, and other actions against the administration in British-occupied India.

Shortly after its inception, the organisation became the focus of an extensive police and intelligence operation which led to the founding of the Special branch of the Calcutta Police. Notable officers who led the police and intelligence operations against the Samiti at various times included Sir Robert Nathan, Sir Harold Stuart, Sir Charles Stevenson-Moore and Sir Charles Tegart. The threat posed by the activities of the Samiti in Bengal during World War I, along with the threat of a Ghadarite uprising in Punjab, led to the passage of Defence of India Act 1915. These measures enabled the arrest, internment, transportation and execution of a number of revolutionaries linked to the organisation, which crushed the East Bengal Branch. In the aftermath of the war, the Rowlatt committee recommended extending the Defence of India Act (as the Rowlatt Act) to thwart any possible revival of the Samiti in Bengal and the Ghadarite movement in Punjab. After the war, the activities of the party led to the implementation of the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment in the early 1920s, which reinstated the powers of incarceration and detention from the Defence of India Act. However, the Anushilan Samiti gradually disseminated into the Gandhian movement. Some of its members left for the Indian National Congress then led by Subhas Chandra Bose, while others identified more closely with Communism. The Jugantar branch formally dissolved in 1938. In independent India, the party in West Bengal evolved into the Revolutionary Socialist Party, while the Eastern Branch later evolved into the Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal (Workers and Peasants Socialist Party) in present-day Bangladesh.

-- Anushilan Samiti, by Wikipedia

According to Daly's Report: "A secret meeting was held in Calcutta about the year 1900 [...] The meeting resolved to start secret societies with the object of assassinating officials and supporters of Government [...] One of the first to flourish was at Kushtea, in the Nadia district. This was organised by one Jotindra Nath Mukherjee [sic!].".[9] Nixon reports further: "The earliest known attempts in Bengal to promote societies for political or semi-political ends are associated with the names of the late P. Mitter, Barrister-at-Law, Miss Saralabala Ghosal and a Japanese named Okakura. These activities commenced in Calcutta somewhere about the year 1900, and are said to have spread to many of the districts of Bengal and to have flourished particularly at Kushtia, where Jatindra Nath Mukharji [sic!] was leader."[10] Bhavabhushan Mitra's written notes precise his presence along with Jatindra Nath during the first meeting. A branch of this organisation (Anushilan Samiti), was to be inaugurated in Dacca. In 1903, on meeting Sri Aurobindo at Yogendra Vidyabhushan's place, Jatin decides to collaborate with him and is said to have added to his programme the clause of winning over the Indian soldiers of the British regiments in favour of an insurrection. W. Sealy in his report on "Connections with Bihar and Orissa" notes that Jatin Mukherjee "a close confederate of Nani Gopal Sen Gupta of the Howrah Gang (...) worked directly under the orders of Aurobindo Ghosh [Sri Aurobindo]."[11]...

Jatin, together with Barindra Ghosh, set up a bomb factory near Deoghar, while Barin was to do the same at Maniktala in Calcutta. Whereas Jatin disapproved of all untimely terrorist action, Barin led an organisation centred around his own personality: his aim was, aside from the general production of terror, the elimination of certain Indian and British officers serving the Crown. Side by side, Jatin developed a decentralised federated body of loose autonomous regional cells. Organising relentless relief missions with a paramedical body of volunteers following almost a military discipline, during natural calamities such as floods, epidemics, or religious congregations like the Ardhodaya and the Kumbha Mela, or the annual celebration of Ramakrishna's birth, Jatin was suspected of utilising these as pretexts for group discussions with regional leaders and recruiting new freedom fighters to fight the supporters of the Britain.[14][15]

-- Bagha Jatin, by Wikipedia

The headquarters of Jugantar was located at 27 Kanai Dhar Lane, then 41 Champatola 1st Lane, Kolkata.[3]

Activities

The Jugantar party possessed cast iron bombshells those manufactured in 1930 by themselves.

Some senior members of the group were sent abroad for political and military training. One of the first batches included Surendra Mohan Bose, Tarak Nath Das and Guran Ditt Kumar, who, since 1907, were extremely active among the Hindu and Sikh immigrants on the Western coast of North America. These units were to compose the future Ghadar Party.[4] In Paris Hemchandra Kanungo alias Hem Das, along with Pandurang M. Bapat, obtained training in explosives from the Russian anarchist Nicholas Safranski. (Source: Ker, p397.) After returning to Kolkata, he joined the combined school of 'self-culture' (anushilan) and bomb factory run by Barin Ghosh at a garden house in Maniktala, a suburb of Calcutta. However, the attempted murder of Kingsford, the-then district Judge of Muzaffarpur by Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki (30 April 1908) initiated a police investigation that led to the arrest of many of the revolutionaries. The prisoners were tried in the famous Alipore bomb conspiracy case in which several activists were deported for life to the Cellular Jail in Andaman.

In 1908, as a next step, Jugantar chose to censure persons connected with the arrest and trial of revolutionaries involved in the Alipore Bomb Case. On 10 February 1909, Ashutosh Biswas, who conducted the prosecution of Kanai and Satyen for the murder of Naren Gosain (a revolutionary turned approver), was shot dead by Charu Basu in the Calcutta High Court premises. Samsul Alam, Deputy Superintendent of Police, who conducted the Alipore Case was shot and killed by Biren Dutta Gupta on the stairs of Calcutta High Court building on 24 January 1910. Charu Basu and Biren Dutta Gupta were later hanged.[5]

Several including Jatindra Nath Mukherjee were arrested in connection with the murder of Police inspector Samsul Alam on 24 January 1910 in Calcutta and other charges. Thus started the Howrah-Sibpur Conspiracy case that tried the prisoners for treason, waging war against the Crown and tampering with the loyalty of Indian soldiers, such as those belonging to the Jat Regiment posted in Fort William, and soldiers in Upper Indian Cantonments.[6]

The German Plot

Main article: Hindu German Conspiracy

Nixon's Report corroborates that Jugantar under Jatindra Nath Mukherjee counted a good deal on the ensuing World War to organise an armed uprising with the Indian soldiers in various regiments.[7] During World War I the Jugantar Party arranged importation of German arms and ammunitions[8] (notably the 32 bore German automatic pistols) via Virendranath Chattopadhyay alias Chatto and other revolutionaries residing in Germany. They had contacted Indian revolutionaries active in the United States, as well as Jugantar leaders in Kolkata. Jatindra Nath Mukherjee informed Rash Behari Bose to take charge of Upper India, aiming at an All-Indian Insurrection with the collaboration of native soldiers in different cantonments. History refers to it as the Hindu German Conspiracy. To raise fund, the Jugantar party organized a series of dacoities which came to be known as Taxicab dacoities and Boat dacoities, in order to procure funds to prepare the ground for working out the Indo-German Conspiracy.

The first of the Taxicab dacoities took place at Garden Reach, Kolkata on 12 February 1915, by a group of armed revolutionaries under the leadership of Narendra Bhattacharya under the direct supervision of Jatindranath Mukherjee [Bagha Jatin]. Similar dacoities were organized on different occasions and in various parts of Calcutta. Dacoities were accompanied by political murders in which the victims were mostly zealous police officers investigating into the cases, or approvers who helped the police.

Failure of the German plot

On receiving instructions from Berlin, Jatindra Nath Mukherjee selected Naren Bhattacharya (alias M. N. Roy) and Phani Chakravarti (alias Pyne) to meet the German legation at Batavia. The Berlin committee had decided that the German arms were to be delivered at two or three places like Hatia on Chittagong coast, Raimangal in the Sunderbans and Balasore in Orissa. The plan was to organize a guerrilla force to start an uprising in the country, backed by a mutiny among the Indian Armed Force. The whole plot leaked out locally owing to a native traitor and, internationally, through the Czech revolutionaries who were in touch with their counterparts in the United States,[9] and as soon as the information reached the British authorities, they alerted the police, particularly in the delta region of the Ganges, and sealed all the sea approaches on the eastern coast from Noakhali-Chittagong side to Orissa. Sramajibi Samabaya and Harry & Sons of Calcutta, the two business concerns run respectively by Amarendra Chatterjee and Harikumar Chakrabarti which were taking an active part in the Indo-German Conspiracy were searched. The police came to know that Bagha Jatin was in Balasore waiting for a German arms delivery. Police went on to find out the hiding places of Bagha Jatin and associates and after a gun-fight, the revolutionaries were either killed or arrested. The German plot thus failed.

After the First World War

The revolution suffered grievous blows with the death or arrest of some of their important leaders. In effect, they had been divided into two groups with distinct convictions. The Dhaka Anushilan Samiti in Eastern Bengal did not participate in the Indo-German plan that the Jugantar in Western Bengal promoted.

In 1920, leaders of the Jugantar Party suspended all violent action, having accepted to follow the Non-Cooperation movement proposed by Gandhi, compatible with their revolutionary hope to organise a mass movement.

Unification and failure

Following these major setbacks, and in the new circumstances of the colonial powers practising their divide and rule policy, there was an attempt to unify the revolutionary factions in Bengal. Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were brought close by the joint leadership of Narendra Mohan Sen of Anushilan, represented by Rabindra Mohan Sen and Jadugopal Mukherjee of Jugantar, represented by Bhupendra Kumar Datta. However, this merger failed to revive the revolutionary activities up to the expected level.[10]

Neo-violence

The younger generation of the revolutionaries were frustrated by the failure of the attempted merger. This led to the formation of a new confederation in 1929, called the neo-violence party.

Later activities

In 1930, as an antidote promised to Gandhi's policy, Jugantar group prepared programmes for further violent revolutionary acts of opposing British occupation. The plans included murder of Europeans; burning of the Dum-Dum aerodrome; destroying the electricity, gas and petrol supplies of Kolkata; disorganisation of tram services in Kolkata by cutting overhead wires; damaging the communication system by destroying telegraph lines, railway tracks etc.

The outcome of such programmes culminated in several attacks. The Chittagong armoury raid by Surya Sen and his followers deserves special mention in this regard.

The scenario changed with the years. The British were planning to quit India, while communal and religious politics came into play. The basic political background on which revolutionary ideas were founded seemed to evolve towards a new direction. The Revolutionaries can thus be said to have come to an end by 1936. The Jugantar officially merged with the Congress on 9 September 1938.

References

1. Chaudhuri,Chattalesh https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli ... 3_djvu.txt

2. Shah, Mohammad (2012). "Jugantar Party". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

3. Mukhopadhyay Haridas & Mukhopadhyay Uma. (1972) Bharater svadhinata andolané 'jugantar' patrikar dan, p15.

4. Political Trouble in India , by James Campbell Ker, pp220-260.

5. Rowlatt Report; Samanta, op. cit.

6. The major charge... during the trial (1910–1911) was "conspiracy to wage war against the King-Emperor" and "tampering with the loyalty of the Indian soldiers" (mainly with the 10th Jats Regiment) (cf: Sedition Committee Report, 1918)

7. Samanta, op. cit. Vol II, p 591

8. Rowlatt Report (§109-110)

9. Spy and Counter-Spy by E.V. Voska and W. Irwin, pp98, 108, 120, 122–123, 126–127; The Making of a State by T.G. Masaryk, pp50, 221, 242; Indian Revolutionaries Abroad by A.C. Bose, pp232–233

10. Islam, Sirajul (2012). "Revolutionary Terrorism". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.