by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/25/20

The Most Reverend and Right Honourable William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury

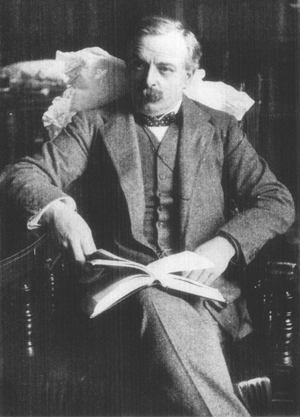

William Temple

Appointed: 1 April 1942 (nominated)

Installed: 17 April 1942 (confirmed)

Term ended: 26 October 1944

Predecessor: Cosmo Lang

Successor: Geoffrey Fisher

Orders

Ordination: 1909 (deacon), 1910 (priest)

Consecration: 25 January 1921

Personal details

Born: 15 October 1881, Exeter, Devon, England

Died: 26 October 1944 (aged 63), Westgate-on-Sea, Kent, England

Buried: Canterbury Cathedral

Nationality: English

Denomination: Church of England

Spouse: Frances Anson

Previous post: Bishop of Manchester, Archbishop of York

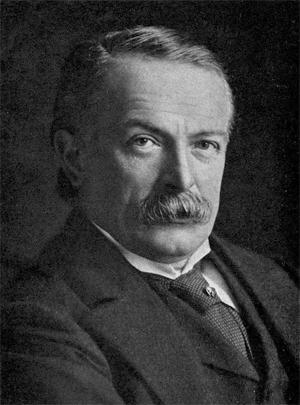

William Temple (15 October 1881 – 26 October 1944) was an English Anglican priest, who served as Bishop of Manchester (1921–1929), Archbishop of York (1929–1942) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1942–1944).

The son of an Archbishop of Canterbury, Temple had a traditional education after which he was briefly a lecturer at the University of Oxford before becoming headmaster of Repton School from 1910 to 1914. After serving as a parish priest in London from 1914 to 1917 and as a canon of Westminster Abbey, he was appointed Bishop of Manchester in 1921. He worked for improved social conditions for workers and for closer ties with other Christian Churches. Despite his socialist sympathies he was nominated by the Conservative government for the Archbishopric of York in 1928 and took office the following year. In 1942 he was translated to be Archbishop of Canterbury, and died in post after two and a half years, aged 63.

Temple was admired and respected for his scholarly writing, his inspirational teaching and preaching, for his constant concern for those in need or under persecution, and for his willingness to stand up on their behalf to governments at home and abroad.

Early years

Temple was born on 15 October 1881 in Exeter, Devon, the second son of Frederick Temple and his wife Beatrice, née Lascelles. Frederick Temple was Bishop of Exeter, and later (1896–1902) Archbishop of Canterbury. Despite the considerable age gap – the Bishop was 59 years old when Temple was born (Beatrice Temple was 35) – they had a close relationship.[1] Sixty years later Temple referred to his father as "among men the chief inspiration of my life".[1] In a centenary appraisal Frederick Dillistone wrote:

Both parents came from aristocratic families and William's life, until he was 21, was spent in episcopal palaces. Yet it is clear that this privileged start did not spoil him, for there was no trace of snobbery or class-consciousness in his later years. Rather, there came to be an increasing concern for all who had not shared his circumstances.[2]

After a preparatory school, Colet Court, Temple went to Rugby School (1894–1900), where his godfather, John Percival was headmaster. Temple later wrote a biography of him.[3] At Rugby, Temple began lifelong friendships with the future historian R. H. Tawney and J. L. Stocks, who became a philosopher and academic.[4]

In 1900 Temple went up to Balliol College, Oxford, where he obtained a double first in classics and served as president of the Oxford Union.[4] The master of Balliol was the philosopher Edward Caird; the biographer Adrian Hastings comments that Caird's neo-Hegelian idealism provided the philosophical inspiration for many of Temple's academic writings.[3] Temple learned to search for a synthesis in apparently conflicting theories or ideals, and later wrote of "my habitual tendency to discover that everybody is quite right – but I was brought up by Caird and I can never get out of that habit".[5] In Dillistone's view, Temple did not make "any radical distinction between Christianity and the World, the Church and the State, Theology and Philosophy, Religion and Culture".[2]

While an undergraduate Temple developed a deep concern for social problems, involving himself in the work of the Oxford and Bermonsdey Mission, which brought material and spiritual help to the poor of the East End of London.

The Mission in Bermondsey

After a meeting of two old friends – Henry Gibbon and Edwyn Barclay – from Wycliffe Hall in 1897, John [Stansfeld] received an invitation to found a small medical mission in Bermondsey, then one of the poorest boroughs of London. The so-called Oxford Medical Mission was started in a small house on Abbey Road with the purpose to ’primarily spread Christ’s Kingdom.’

John’s days were packed with activity – he worked for Customs & Excise during the day and ran a medical surgery and boys club in Bermondsey in the evenings. Those who knew him said that they never saw him sleep! However, he managed to find time to marry Janet Marples, a social worker in Bermondsey, in 1902, and in 1903 their first son, John Gordon Stansfeld, was born followed three years later by a daughter, called Phyllis Janet Stansfeld. For the next sixteen years, John and Janet worked side by side rearing their family and trying to help improve the lives of the residents of Bermondsey.

At the turn of the century, John surprised his colleagues at the mission by buying a piece of land in Horndon-on-the-Hill in Essex in order to create a boys summer camp. He wanted to give the deprived children of the parish a haven away from the city -– a place to escape, explore and enjoy. On the site, he built a ’castle’ from the wreckage of an old Bermondsey church. He also built Wycliffe House -– a long, low hut suitable for meals and gatherings. John obviously had great foresight as this was a few years before Baden Powell formed the Scouts, a movement that made camping and outdoor exploration for young boys popular all around the UK. In 1903 he extended the original Bermondsey mission to another site at Dockhead, just east of Tower Bridge, and other outposts followed.

-- The Story of John Stansfeld, The Man Behind Stansfeld Park, by TheOxfordTrust.co.Uk

Another enduring interest that began in this period was his concern to make higher education available to intellectually able students from all social and economic backgrounds.[6]

Oxford and Repton: 1904–1914

After taking his degree in 1904 Temple received numerous job offers – one biographer says as many as 30[5] – and he opted for a fellowship at Queen's College, Oxford, where he went into residence as fellow and lecturer in philosophy in October 1904, remaining there until 1910. According to Hastings his lectures were ostensibly on Plato's Republic but in reality were on his own mix of Greek and Christian themes.[3] His tutorial duties were light, and he had leisure to visit mainland Europe and meet philosophers and theologians such as Rudolf Christoph Eucken, Hans Hinrich Wendt, Adolf von Harnack and Georg Simmel.[5]

For as long as he could remember, Temple had aimed to be ordained, and in January 1906 he approached the Bishop of Oxford, Francis Paget, seeking admission to the diaconate. Paget declined, expressing regret that he could not ordain anyone with such theological views as those of Temple, who was hesitant about accepting the literal truth of the Virgin birth or the bodily resurrection of Christ. After further study, and guidance from the Oxford theologians Henry Scott Holland and Burnett Hillman Streeter, Temple felt ready to try again and in March 1908 he obtained an interview with his father's successor as Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson. After an exchange of letters between Davidson and Paget, the Archbishop made Temple a deacon on 20 December 1908 in Canterbury Cathedral, and ordained him priest on 19 December 1909.[5]

In 1908 Temple became the first president of the newly formed Workers' Educational Association, a charity dedicated to making the best educational opportunities available to all.[6] In 1910 he published his first book, The Faith and Modern Thought. The Athenaeum took issue with some of his contentions, but considered that writers like him demonstrated that "a fresh presentation of doctrine may be helpful to religion, and not injurious".[7] The Saturday Review enjoyed the book's "vigorous and exuberant healthiness" and predicted, "Matured experience will enable the author to give the world some remarkable work".[8]

In June 1910 Lionel Ford, the headmaster of Repton School, moved to the headship of Harrow, and Temple was appointed to succeed him at Repton.[9] The biographer George Bell quotes a Repton colleague on Temple:

He was not really fitted, either by temperament or by taste, to be a great headmaster, as he probably soon discovered. He was never really interested in the administrative details of an educational institution, and he had too many wider interests in the outside world to settle down to them, but, both in chapel and in the classroom, and most of all perhaps in his familiar intercourse with the senior boys, he was a source of real inspiration to many at Repton. He made a host of life-long friends there, and his Repton years were among the happiest in a fundamentally happy life.[10]

Temple shared his colleague's reservations about his suitability for the post; in late 1910, during his first term at Repton, he wrote "I doubt whether headmastering is really my line".[3] On 1 January 1913 it was announced that he had been appointed vicar of St Margaret's, Westminster, a post that carried with it one of the canonries of the adjacent Westminster Abbey, but it then emerged that the Abbey statutes required all canons to have served at least six years in holy orders.[11] Temple remained at Repton for another 18 months, and then accepted the benefice of St James's, Piccadilly in the West End of London. He was happy to be succeeded as headmaster by Geoffrey Fisher.[11][12]

Piccadilly and Westminster Abbey: 1914–1920

The Piccadilly parish was undemanding, and left Temple free to write and to work on national issues during the early part of the First World War, especially for the National Mission of Repentance and Hope, an initiative designed to renew Christian faith nationwide.[11]

In the autumn of 1916 the Church of England called the nation to a National Mission of Repentance and Hope. The Mission was launched by the Archbishop of Canterbury Randall Davidson and Cosmo Lang, the Archbishop of York, as an attempt to repent for our sins as a nation:‘We are to repent not because we believe that we are guilty of provoking this war, but because we, together with the other nations that profess to be Christian, have failed to learn how to live together as a Christian family, how to set forth Christ to the peoples who do not know Him. We are to repent because, in the light of the war, we are learning to know our sins as a nation. Because it is clear that the spirit of love does not rule our relations with one another at home, any more than it rules the relations between the nations.’

As well as repentance, the National Mission projected a much needed message of hope during the grave time of war. The perils of war lowered public morale and tested the faith of many Christians. The Church believed that a collective national effort is required to combat this bleak sentiment. ‘The war deepened the Church’s sense that society needed its pastoral role.’ The Church had hoped to reconnect with the nation and re-awaken Christian conscience:‘We look forward to a new England, to a new world. Our repentance will open the way for the Holy Spirit to show us how we can help to make that new England, that new world.’

The message of the National Mission of Repentance and Hope invited the nation on a Mission of Witness, to earnestly reflect on their attitudes, weaknesses, and passions, and to repent in hope of a better world. The Church’s sentiment of hoping for a better world mirrored the reason why many conscripted -- in a hope to fight to save their country and the world. The National Mission was very much a home front initiative but was also a message for the trenches. The war was an opportunity to renew the Christian faith: to learn the lesson taught to us by war through examining ourselves as a nation and taking the lesson to heart. The words of the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, in his Presidential Address, sum up the fundamental idea behind Anglican Witness: ‘To be a Christian is to believe we are commanded and authorised to say certain things to the world; to say things that will make disciples of all nations.’3. But our further hope lies in the latent and unconscious Christianity in the nation itself. "Nothing is of any use, but prayer and trust in God; we all feel it out here; war is a great purge," so wrote an Oxford undergraduate from the trenches to me the other day; and this is only a sample of numbers of such letters.

If only anything like the call to reality which has been heard at the Front can be made vocal at home, there is a latent Christianity in the Anglo-Saxon race which will answer to the call; it is not mere sentimentality, but something deeper, which makes a group of soldiers on a Sunday night ready to sing hymns; nor do the crowded churches on a watch night or a harvest festival represent pure superstition. This mission, then, is to be like the coming of the spring; it is to be a drawing-out of sweet influences and powers, inherent but dormant in the Church and nation. Its effect is not to be produced primarily by the beating of big drums, or the oratory of mission preachers; each diocese is to revive itself in its own way, believing that under the breath of the life-giving Spirit even "a desert may rejoice and blossom as the rose."

-- An excerpt of an article from Church Times, March 1916, by the Bishop of London (Arthur-Winnington Ingram) [Davidson 772 f.85]

The organisation of the National Mission was an enormous undertaking. The Bishop of London, Arthur-Winnington Ingram, took the role of Chairman of the Central Council and a panel of Archbishops’ Messengers was set up specifically for the purpose of the National Mission. A large body of literature was provided at [the] national level; posters, postcards, resolution cards, pamphlets, hymn books, children’s books, and study guides. The date of the Mission was to be between October and November 1916 with the clergy preparing first and dioceses following with their own arrangements. Once the arrangements had been made, it was decided that the Mission would go ahead with the help of the newly established general Consultative Committee and five Archbishops’ Committees of Enquiry.

-- The National Mission of Repentance and Hope 1916, by A Monument of Fame: The Lambeth Palace Library Blog, May 13, 2016

Blood shone at me from the red light of the crystal, and when I picked it up to discover its mystery, there lay the horror uncovered before me: in the depths of what is to come lay murder. The blond hero lay slain. The black beetle is the death that is necessary for renewal; and so thereafter, a new sun glowed, the sun of the depths, full of riddles, a sun of the night. And as the rising sun of spring quickens the dead earth, so the sun of the depths quickened the dead, and thus began the terrible struggle between light and darkness. Out of that burst the powerful and ever unvanquished source of blood. This was what was to come, which you now experience in your life, and it is even more than that. (I had this vision on the night of 12 December 1913.)...

In the year 1914 in the month of June, at the beginning and end of the month, and at the beginning of July, I had the same dream three times: I was in a foreign land, and suddenly, overnight and right in the middle of summer, a terrible cold descended from space. All seas and rivers were locked in ice, every green living thing had frozen.

The second dream was thoroughly similar to this. But the third dream at the beginning of July went as follows:

I was in a remote English land. It was necessary that I return to my homeland with a fast ship as speedily as possible. I reached home quickly. In my homeland I found that in the middle of summer a terrible cold had fallen from space, which had turned every living thing into ice. There stood a leaf-bearing but fruitless tree, whose leaves had turned into sweet grapes full of healing juice through the working of the frost. I picked some grapes and gave them to a great waiting throng.

In reality, now, it was so: At the time when the great war broke out between the peoples of Europe, I found myself in Scotland, compelled by the war to choose the fastest ship and the shortest route home. I encountered the colossal cold that froze everything, I met up with the flood, the sea of blood, and found my barren tree whose leaves the frost had transformed into a remedy. And I plucked the ripe fruit and gave it to you and I do not know what I poured out for you, what bitter-sweet intoxicating drink which left on your tongues an aftertaste of blood....

Therefore the spirit foretold to me that the cold of outer space will spread across the earth. With this he showed me in an image that the God will step between men and drive every individual with the whip of icy cold to the warmth of his own monastic hearth.

-- The Red Book: Liber Novus, by C.G. Jung

He served as editor of The Challenge, a non-party Church newspaper, which foundered after two and a half years.[5] He was more successful with the Life and Liberty Movement, a campaign for a measure of independence for the Church of England, which was at that time wholly under the control of Parliament for its laws and rules. In 1916 he married Frances Gertrude Acland Anson (1890–1984). They had no children. The following year Temple gave up the rectorship of St James's to make himself free to tour the country campaigning for Life and Liberty.[13] In the same year he completed his largest philosophical work, Mens Creatrix (The Creative Mind). In 1918 he joined the Labour Party,[14] and remained a member for eight years.[5]

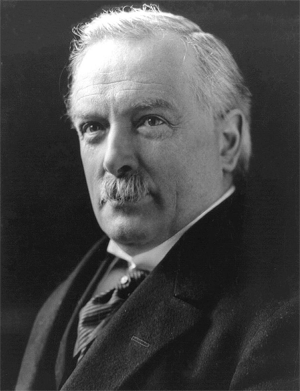

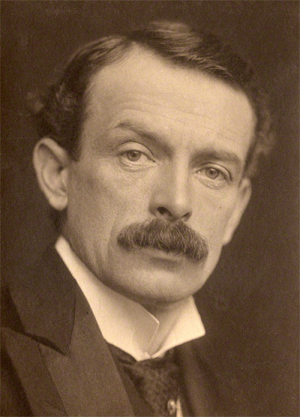

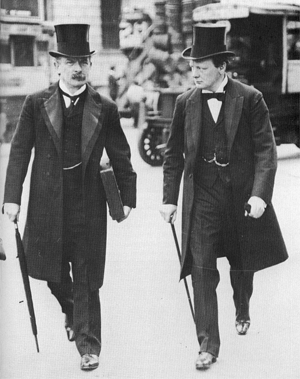

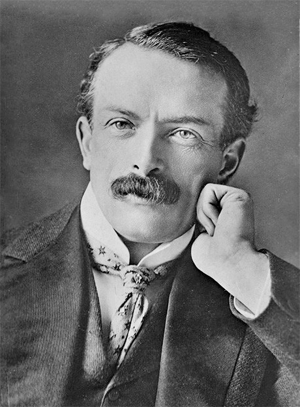

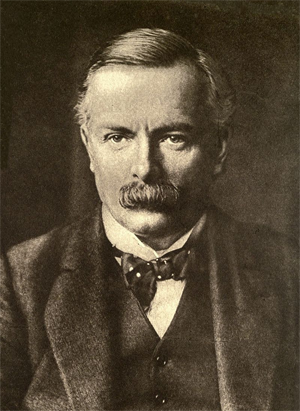

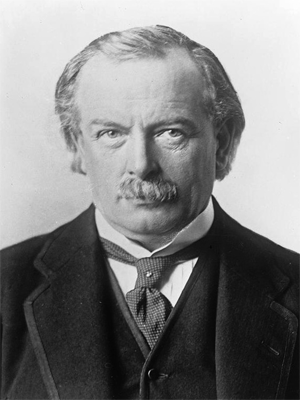

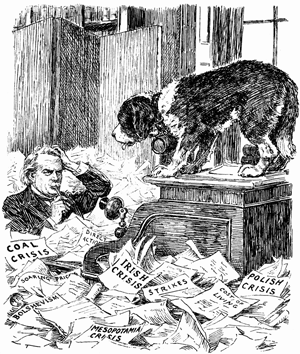

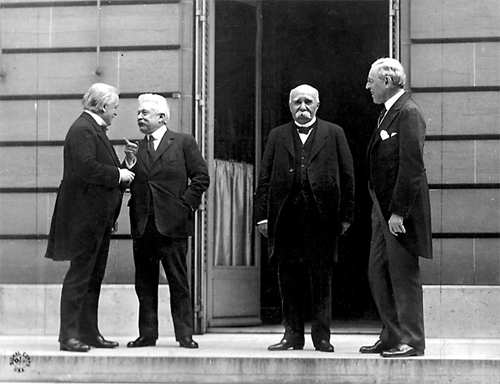

Temple's appointment as a canon of Westminster in June 1919 further raised his public profile. The Abbey was crowded whenever he preached.[5] Hastings writes that it was clear to Archbishop Davidson that so able and influential a man as Temple should be found a suitably important role. Towards the end of 1920, when Temple was 39, the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, offered him the post of Bishop of Manchester.[3]

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, OM, PC (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was a British statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom between 1916 and 1922. He was the final Liberal to hold the post.

-- David Lloyd George

[W]e shall generally call the organization the "Rhodes secret society" before 1901 and "the Milner Group" after this date, but it must be understood that both terms refer to the same organization.

This organization has been able to conceal its existence quite successfully, and many of its most influential members, satisfied to possess the reality rather than the appearance of power, are unknown even to close students of British history. This is the more surprising when we learn that one of the chief methods by which this Group works has been through propaganda. It plotted the Jameson Raid of 1895; it caused the Boer War of 1899-1902; it set up and controls the Rhodes Trust; it created the Union of South Africa in 1906-1910; it established the South African periodical The State in 1908; it founded the British Empire periodical The Round Table in 1910, and this remains the mouthpiece of the Group; it has been the most powerful single influence in All Souls, Balliol, and New Colleges at Oxford for more than a generation; it has controlled The Times for more than fifty years, with the exception of the three years 1919-1922, it publicized the idea of and the name "British Commonwealth of Nations" in the period 1908-1918, it was the chief influence in Lloyd George's war administration in 1917-1919 and dominated the British delegation to the Peace Conference of 1919; it had a great deal to do with the formation and management of the League of Nations and of the system of mandates; it founded the Royal Institute of International Affairs in 1919 and still controls it; it was one of the chief influences on British policy toward Ireland, Palestine, and India in the period 1917-1945; it was a very important influence on the policy of appeasement of Germany during the years 1920-1940; and it controlled and still controls, to a very considerable extent, the sources and the writing of the history of British Imperial and foreign policy since the Boer War....

As High Commissioner, Milner built up a body of assistants known in history as "Milner's Kindergarten." The following list gives the chief members of the Kindergarten, their dates of birth and death (where possible), their undergraduate colleges (with dates), and the dates in which they were Fellows of All Souls....

Of these twenty-three names, eleven were from New College. Seven were members of All Souls, six as Fellows. These six had held their fellowships by 1947 an aggregate of one hundred and sixty-nine years, or an average of over twenty-eight years each. Of the twenty-three, nine were in the group which founded, edited, and wrote The Round Table in the period after 1910, five were in close personal contact with Lloyd George (two in succession as private secretaries) in the period 1916-1922, and seven were in the group which controlled and edited The Times after 1912....

In 1915, Lloyd George sent Hichens and Brand to organize the munitions industry of Canada. They set up the Imperial Munitions Board of Canada, on which Joseph Flavelle (Sir Joseph after 1917) was made chairman, Charles B. Gordon (Sir Charles after 1917) vice-chairman, and Brand a member....

From 1908 on, Kerr [Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian)] was, as we shall see, one of the chief organizers of publicity in favor of the South African Union. He was secretary to the Round Table Group in London and editor of The Round Table from 1910 to 1916, leaving the post to become secretary to Lloyd George (1916-1922), manager of the Daily Chronicle (1921), and secretary to the Rhodes Trust (1925-1939)...

Edward William Mackay Grigg (Sir Edward after 1920, Lord Altrincham since 1945) is one of the most important members of the Milner Group. On graduating from New College, he joined the staff of The Times and remained with it for ten years (1903-1913), except for an interval during which he went to South Africa. In 1913 he became joint editor of The Round Table, but eventually left to fight the war in the Grenadier Guards. In 1919, he went with the Prince of Wales on a tour of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. After replacing Kerr for a year or so as secretary to Lloyd George (1921-1922), he was a Member of Parliament in 1922-1925 and again in 1933-1945....

In the new government formed after the creation of the Union of South Africa, [Jan] Smuts held three out of nine portfolios (Mines, Defense, and Interior). In 1912 he gave up two of these (Mines and Interior) in exchange for the portfolio of Finance, which he held until the outbreak of war. As Minister of Defense (1910-1920) and Prime Minister (1919- 1924), he commanded the British forces in East Africa (1916-1917) and was the South African representative and one of the chief members of the Imperial War Cabinet (1917- 1918). At the Peace Conference at Paris he was a plenipotentiary and played a very important role behind the scenes in cooperation with other members of the Milner Group. In 1921 he went on a secret mission to Ireland and arranged for an armistice and opened negotiations between Lloyd George and the Irish leaders....

William George Stewart Adams was lecturer in Economics at Chicago and Manchester universities and Superintendent of Statistics and Intelligence in the Department of Agriculture before he was elected to All Souls in 1910. Then he was Gladstone Professor of Political Theory and Institutions (1912-1933), a member of the committee to advise the Irish Cabinet (191 1), in the Ministry of Munitions (1915), Secretary to Lloyd George (1916-1919), editor of the War Cabinet Reports (1917-1918), and a member of the Committee on Civil Service Examinations (1918)...

Brand [Robert Henry Brand (Lord Brand)] was apparently the one who brought [Lord] Astor into the Milner Group in 1917, although there had been a movement in this direction considerably earlier. Astor was a Conservative M.P. from 1910 to 1919, leaving the Lower House to take his father's seat in the House of Lords. His place in Commons has been held since 1919 by his wife, Nancy Astor (1919-1945), and by his son Michael Langhorne Astor (1945- ). In 1918 Astor became parliamentary secretary to Lloyd George; later he held the same position with the Ministry of Food (1918-1919) and the Ministry of Health (1919-1921)....

[Alfred] Milner himself became the second most important figure in the government (after Lloyd George)[/size][/b], especially while he was Minister without Portfolio. He was chiefly interested in food policy, war trade regulations, and postwar settlements. He was chairman of a committee to increase home production of food (1915) and of a committee on postwar reconstruction (1916). From the former came the food- growing policy adopted in 1917, and from the latter came the Ministry of Health set up in 1919. In 1917 he went with Lloyd George to a meeting of the Allied War Council in Rome and from there on a mission to Russia...Throughout this period Milner's opinion of Lloyd George was on the highest level. Writing twenty years later in The Commonwealth of God, Lionel Curtis recorded two occasions in which Milner praised Lloyd George in the highest terms. On one of these he called him a greater war leader than Chatham.

At this period it was not always possible to distinguish between the Cecil Bloc and the Milner Group, but it is notable that the members of the former who were later clearly members of the latter were generally in the fields in which Milner was most interested. In general, Milner and his Group dominated Lloyd George during the period from 1917 to 1921. As Prime Minister, Lloyd George had three members of the Group as his secretaries (P. H. Kerr, 1916-1922; W. G. S. Adams, 1916-1919; E. W. M. Grigg, 1921- 1922) and Waldorf Astor as his parliamentary secretary (1917-1918). The chief decisions were made by the War Cabinet and Imperial War Cabinet, whose membership merged and fluctuated but in 1917-1918 consisted of Lloyd George, Milner, Curzon, and Smuts — that is, two members of the Milner Group, one of the Cecil Bloc, with the Prime Minister himself.

-- The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden, by Carroll Quigley

Bishop of Manchester: 1921–1929

Temple was consecrated bishop at York Minster on 25 January 1921 and enthroned at Manchester Cathedral on 15 February.[15] The Church Times later commented, "None of his friends doubted that if he would stick to his new job, and not be lured into a hundred-and-one other activities, he would make a big success".[16] In the view of the same writer':

Throughout the seven years he ruled the diocese he was a true Father-in-God. Whatever tended to the promotion of the work of the Church had his support. Thus he accepted the presidency of the Anglo-Catholic Congress on the two occasions it was held in Manchester, and remained for years president of its diocesan committee.[16]

Temple came as a sharp contrast with his predecessor, Edmund Knox. Knox had been staunchly evangelical and autocratic. He had refused to countenance the division of his over-large diocese; Temple saw that division was essential and founded the separate Diocese of Blackburn in 1926. Hastings comments that while "showing himself a thoroughly pastoral bishop, for whom parish visiting had a high priority",[3] Temple had wider social and ecumenical agendas. Manchester was a better fit than Piccadilly for his social concerns. It gave him scope for his interest in industrial relations and how Christian philosophy could help improve them.[16] In 1926, after the BBC vetoed Davidson's proposed broadcast to help mediate in the General Strike, Temple took a leading part with other bishops in trying to bridge the gulf between the miners and coal owners.[16] He co-operated with other Christian bodies, and as a member of the Council of Christian Congregations in his diocese he took an active part in promoting measures of social improvement.[16] He pursued a policy of inclusiveness among Christians, and invited several nonconformist ministers to preach in the Manchester diocese, which prompted the anti-ecumenical Bishop Weston of Zanzibar to withdraw in protest from the Lambeth Conference.[17]

As well as social concerns, Temple played a role in humanitarian and religious concerns. He was a leading figure in missionary conferences, led missions to undergraduates at Cambridge, Oxford and Dublin,[18] and revitalised the annual Blackpool sands mission.[16] In retrospect (1944) The Manchester Guardian expressed reservations about Temple as a diocesan bishop: "he was doing too many things outside his diocese … he was not really interested in humdrum details of administration".[19] Nonetheless, The Church Times said, "No aspect of life in his diocese was without his touch, whether it were in college, factory, conference hall or theatre. And all the time the flow of books from his pen continued, most of the work being done in the odd snatches of time between interviews and engagements, which lesser men fritter away with a cigarette".[16]

Archbishop of York: 1929–1942

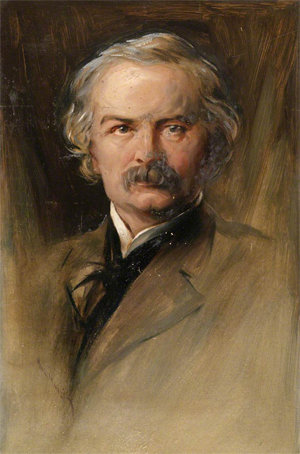

Portrait by Philip de László, 1942

In 1928 Davidson retired, succeeded at Canterbury by Lang, to whom Temple was widely seen as one of six likely successors.[n 1] He had support from all sections of the Church although there was some concern that the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, a Conservative, would not nominate a prominent Labour supporter. Temple was appointed, and was enthroned at York Minster on 10 January 1929.[20]

Hastings writes that Temple's thirteen years at York were "by far the most important and effective in his life".[3] As Archbishop, Temple was in a position to exercise "the sort of national and international leadership for which he was naturally suited". Hastings gives examples ranging from local and national – preaching, lecturing, presiding in parishes, university missions, ecumenical gatherings and chairing the General Advisory Council of the BBC – to international – lecturing in American universities, speaking at the 1932 disarmament conference in Geneva and becoming the recognised leader of the international ecumenical movement. He was one of the instigators of the World Council of Churches as well as the British Council of Churches.[3]

The British Council of Churches (BCC) was an organization established in England in 1942 for the promotion of common action among the Christian churches of Great Britain. It sought to facilitate common evangelical action among the churches, to promote international friendship, to stimulate a sense of social responsibility, to guide youth work, to assist in the growth of ecumenical consciousness, and to promote Christian unity. Various conferences and groupings of the free churches had previously existed, but the BCC brought together the established churches of England and Scotland and the nonconforming churches. Beginning with William Temple, the first president, the presidency was held by the archbishop of Canterbury. The BCC included the Church of England; the Episcopalians of Scotland, Ireland, and Wales; the English Presbyterians; the Presbyterian Church of Scotland; the Methodists; the Congregationalists; the Churches of Christ; the Baptists; the Quakers; the Unitarians; and the Salvation Army. The Greek Orthodox Church became a member in 1965. Associated with the council are also interdenominational societies such as the YMCA, the YWCA, the Student Christian Movement, the Christian Auxiliary Movement, and the Conference of British Missionary Societies.

Roman Catholics were not part of the BCC until 1990, when they were formally admitted. With the inclusion of Roman Catholics, the BCC changed its name to the Council of Churches for Britain and Ireland, and in 1999 they adopted the name Churches Together in Britain and Ireland (CTBI). In addition to building an ecumenical spirit among the member churches, the CTBI has undertaken the task of helping the churches to collaborate in common projects.

-- British Council of Churches, by Encyclopedia.com

While Archbishop of York, in addition to his pastoral work Temple wrote what Hastings regards as his three most enduringly important books: Nature, Man and God (1934), Readings in St John's Gospel (1939 and 1940), and Christianity and Social Order (1942). The first of these was compiled from his Gifford lectures given in Glasgow between November 1932 and March 1934;[3] The Manchester Guardian called it "a fine example of [Temple's] astonishing vigour and versatility" and quoted Dean Inge's comment, "It would be a great achievement for a university professor; for a ruler of the Church it is astonishing".[19] Christianity and Social Order sought to marry faith and socialism and rapidly sold around 140,000 copies.[21]

Temple's contributions in the social field during his time as Archbishop of York included working with a specialist committee and the Pilgrim Trust to produce a report on unemployment, Men without Work (1938), and convening and chairing the Malvern conference (1941) on church and society. The latter proposed six requisites for a society based on Christianity: every child should find itself a member of a family housed with decency and dignity; every child should have an opportunity for education up to maturity; every citizen should have sufficient income to make a home and bring up his children properly; every worker should have a voice in the conduct of the business or industry in which he works; every citizen should have sufficient leisure – two days' rest in seven and annual holiday with pay; every citizen should be guaranteed freedom of worship, speech, assembly, and association.[22]

The Pilgrim Trust is a national grant-making trust in the United Kingdom. It is based in London and is a registered charity under English law.[1]

It was founded in 1930 with a two million pound grant by Edward Harkness, an American philanthropist. The trust's inaugural board were Stanley Baldwin, Sir James Irvine, Sir Josiah Stamp, John Buchan and Hugh Macmillan;[2] its first secretary was former civil servant, Thomas Jones.[3]

Preamble to Trust Deed

The preamble to the Trust Deed was written by John Buchan, and reads thus:[4]“ Whereas it is acknowledged by all the Great Britain in the War spent her resources freely in the common cause and in the years which have elapsed since Peace has sustained honourably and without complaint a burden which has gravely increased the difficulties of life for her people; And whereas the Donor feels himself bound by many ties of affection to the land from which he draws his descent and desires to show his admiration for what Great Britain has done by a gift to be used for some of her more urgent needs; And whereas he hopes that such a gift wisely applied may assist not only in tiding over the present time of difficulty but in promoting her future well-being... ”

Recording Britain

In 1940 the Trust funded a scheme "Recording the changing face of Britain" established by the Committee for the Employment of Artists in Wartime, part of the Ministry of Labour and National Service. Led by Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery, it employed artists to record the home front in Britain, running until 1943. It was motivated by a desire to record and reflect the landscape, already undergoing a period of rapid change through urbanisation and changes in agriculture and further threatened by bombing and other effects of war. Some of the sixty three artists directly commissioned included John Piper, Sir William Russell Flint, Charles Knight, Malvina Cheek, George Hooper, Clifford Ellis, Raymond Teague Cowern and Rowland Hilder. A further thirty four artists contributed to the final total of over 1500 works. The collection was donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum by the Trust in 1949.[5] Over a hundred works comprising the "Recording Scotland" part of the same scheme are held at the Museum Collections Unit, University of St. Andrews.[6]

The Trust today

Today, the trust makes grants of roughly 2 million pounds each year. Around 60% of these funds are given to preservation projects, particularly those aimed at preserving the fabric of architecturally or historically significant buildings, or those aimed at preserving historically interesting artifacts or documents. The trust has a particular interest in the preservation of historic churches and their contents. The remaining funds are allocated to social welfare causes, particularly projects which assist those misusing alcohol and drugs, and projects in prisons, including those that seek alternatives to custody.[citation needed] The trust is a principal contributor to the collaborative National Cataloguing Grants Scheme operated in conjunction with The National Archives.[7]

-- Pilgrim Trust, by Wikipedia

The Malvern Conference of 1941 brought together leading Anglican social thinkers of the day to explore the Christian basis for involvement in society and Christian responses to pressing social, political and economic issues, some of which influenced thinking behind the post-war welfare state. In 1991, a second Malvern conference was organised to mark the 50th anniversary of William Temple’s original conference, this time with a particular focus on the challenges facing Britain and Europe in the light of the creation of the European Union (EU). In this article, the two Malvern conferences are compared and contrasted for their views on the key challenges of the day, steps towards a more just future and the role of the churches within that process. The article concludes with reflection on the lessons of both conferences for the churches’ engagement in the public square today.

-- Faith in the public square in 1941 and 1991: two Malvern Conferences reviewed, Ian Jones

Archbishop of Canterbury: 1942–1944

Lang retired as Archbishop in March 1942. There had been right-wing political attempts to block Temple's succession;[19][23] he was well aware of this: "some of my recent utterances have not been liked in political circles".[5][n 2] But the overwhelming expectation and desire that Temple should succeed Lang prevailed. His biographer Frederic Iremonger cites Lang's strong recommendation together with Temple's "reputation at home, in the Anglican communion overseas, and in the continental Churches; his prophetic leadership; his wide and massive knowledge … his immense powers of concentration; the personal devotion of his life".[5] The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who was responsible for nominating the new Archbishop, was well aware of Temple's political views, but accepted that he was the outstanding candidate: "the only half a crown article in the sixpenny bazaar".[25][n 3] Temple was enthroned in Canterbury Cathedral on 23 April 1942.[3]

In March 1943, Temple addressed the House of Lords, urging action to be taken on the atrocities being carried out by Nazi Germany.[26] He drew criticism in 1944 from his numerous Quaker connections for writing an introduction to Stephen Hobhouse's book Christ and our Enemies that did not condemn the Allied carpet bombing of Germany; he said that he was "not only non-pacifist but anti-pacifist".[27] He did not deny pacifists' right to refuse to fight, but maintained that they must take responsibility for their renunciation of the use of force. He said that people are responsible not only for what they intend, but for the foreseen results of their activity: if Adolf Hitler remained unopposed and conquered Europe, pacifists had to be willing to accept responsibility for this, in that they had not opposed him.[28]

It may be opportune at this point to say a word about the attitude of a Christian Society towards Pacifism....I cannot but believe that the man who maintains that war is in all circumstances wrong, is in some way repudiating an obligation towards society; and in so far as the society is a Christian society the obligation is so much the more serious. Even if each particular war proves in turn to have been unjustified, yet the idea of a Christian society seems incompatible with the idea of absolute pacifism; for pacifism can only continue to flourish so long as the majority of persons forming a society are not pacifists....The notion of communal responsibility, of the responsibility of every individual for the sins of the society to which he belongs, is one that needs to be more firmly apprehended; and if I share the guilt of my society in time of 'peace', I do not see how I can absolve myself from it in time of war, by abstaining from the common action.

-- The Idea of a Christian Society (1939), by T.S. Eliot

Temple was able to complete the work of [Randall] Davidson [Anglican priest who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1903 to 1928], who had striven unsuccessfully for reform of Britain's fragmented and inadequate primary education systems.[29] Davidson had been impeded by nonconformists' resistance in defence of their own church schools, but by the 1940s the sectarian divide was less rigid, and nonconformist leaders trusted Temple's sense of justice and honesty so that he was able to help negotiate the place of all church schools within the system agreed in the 1944 Education Act.[5]

The Education Act 1944 (7 and 8 Geo 6 c. 31) made numerous major changes in the provision and governance of secondary schools in England and Wales. It is also known as the "Butler Act" after the President of the Board of Education, R. A. Butler. Historians consider it a "triumph for progressive reform," and it became a core element of the post-war consensus supported by all major parties.[1] The Act was repealed in steps with the last parts repealed in 1996.[2]

The basis of the 1944 Education Act was a memorandum entitled Education After the War (commonly referred to as the "Green Book") which was compiled by Board of Education officials and distributed to selected recipients in June 1941.[3] The President of the Board of Education at that time was Butler's predecessor, Herwald Ramsbotham; Butler succeeded him on 20 July 1941. The Green Book formed the basis of the 1943 White Paper, Educational Reconstruction which was itself used to formulate the 1944 Act.[3] The purpose of the Act was to address the country's educational needs amid demands for social reform that had been an issue before the Second World War began. The Act incorporated proposals developed by leading specialists in the 1920s and 1930s such as R. H. Tawney and William Henry Hadow.[4] The text of the Act was drafted by Board of Education officials including Griffiths G. Williams, William Cleary, H. B. Wallis, S. H. Wood, Robert S. Wood, and Maurice Holmes.[5]

There was a desire to keep the churches involved in education but they could not afford to modernise without government help. By negotiation with the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple (1881-1944), and other religious leaders, a majority of the Anglican church schools became voluntary controlled and were effectively absorbed into the state system in return for funding. The Act also encouraged non-sectarian religious teaching in secular schools. A third of the Anglican church schools became voluntary aided which entitled them to enhanced state subsidies whilst retaining autonomy over admissions, curriculum and teacher appointments; Roman Catholic schools also chose this option.[6]

The legislation was enacted in 1944, but its changes were designed to take effect after the war, thus allowing for additional pressure groups to have their influence.[7][8] Paul Addison argues that in the end, the act was widely praised by Conservatives because it honoured religion and social hierarchy, by Labour because it opened new opportunities for working class children, and by the general public because it ended the fees they had to pay for secondary education.

-- Education Act 1944, by Wikipedia

In the war years Temple travelled continually around England, often speaking several times in a single day. He suffered all his life from gout, which under the burdens of his workload grew steadily worse and early in October 1944 he was taken by ambulance from Canterbury to rest at a hotel in Westgate-on-Sea, where he died of a heart attack on 26 October.[30] His funeral service was held in Canterbury Cathedral on 31 October and was led by Lang, together with Cyril Garbett, Archbishop of York, and Hewlett Johnson, Dean of Canterbury. Temple was the first Archbishop of Canterbury to be cremated.[31] His ashes were buried in the cloister at Canterbury Cathedral, next to the grave of his father.[3][32]

Reputation and legacy

Temple's death was followed by tributes not only from within the Church of England but also from the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, Bernard Griffin, from nonconformist leaders, and from the Chief Rabbi, Joseph Hertz, who said, "Dr Temple was a great power for good far beyond the borders of the national church. Israel has lost a true friend and humanity a valiant champion. We shall all bitterly miss him."[19] President Roosevelt wrote to George VI on Temple's death expressing the sympathy of the American people, saying, "As an ardent advocate of international co-operation based on Christian principles he exerted a profound influence throughout the world".[33] Lang was greatly distressed by his successor's death. He wrote, "I don't like to think of the loss to the Church and Nation... But 'God knows and God reigns'".[34]

In a biographical essay, Bishop George Bell wrote:

William Temple was not only one of the greatest men of his day, but also one of the greatest teachers who have ever filled the Archbishopric of Canterbury. His tenure of the see was for no more than two and a half years, yet his influence on the British people, in the field of social justice, on the Christian Church as a whole, and in international relations, was of a kind to which it would be very difficult to find a parallel in the history of England.[1]

Among several enduring memorials to Temple is the William Temple Foundation (formerly the William Temple College) in Manchester, a research and resource centre for those developing discipleship and ministry in an urban industrial society.[35]

Works

• The Faith and Modern Thought (1910)

• The Nature of Personality (1911)

• The Kingdom of God (1914)

• Studies In The Spirit And Truth Of Christianity: Being University And School Sermons (1914)

• Church and Nation (1915)

• Mens Creatrix (1917)

• Fellowship with God (1920)

• Life of Bishop Percival (1921)

• Plato and Christianity, three lectures (1916)

• Personal Religion and the Life of Fellowship (1926),

• Christus Veritas (1924)

• Christianity and the State (1928)

• Christian Faith and life (1931).

• Nature, Man and God Gifford Lectures (1934)

• Men Without Work (1938)

• Readings in St John's Gospel (1939/1940. Complete edition 1945.)

• Christianity and Social Order (1942)

• The Church Looks Forward (1944).

Notes, references and sources

Notes

1. The others were the Bishops of Chelmsford (Guy Warman), Durham (Hensley Henson), Liverpool ( Albert David), Oxford (Thomas Strong) and Winchester (Theodore Woods).[17]

2. The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, allayed his misgivings about Temple by nominating Cyril Garbett for York, as, he hoped, a restraining influence. In fact Garbett was at least as left-wing as Temple, though less outspoken.[24]

3. Iremonger quotes Bernard Shaw: "To a man of my generation an archbishop of Temple's enlightenment was a realized impossibility".[5]

References

1. Baker and Bell, p. 11

2. Dillistone, F. W. "William Temple: A Centenary Appraisal",Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church, June, 1983, pp. 101–112 (subscription required)

3. Hastings, Adrian. "Temple, William (1881–1944), archbishop of Canterbury" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2019 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

4. Baker and Bell, p. 12

5. Iremonger, F. A. "Temple, William (1881–1944)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Macmillan 1959 and Oxford University Press, 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2019. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

6.Baker and Bell, p. 14

7. "The Faith and Modern Thought Six Lectures by William Temple", The Athenaeum, 23 April 1910, pp. 489–490

8. "The Faith and Modern Thought Six Lectures by William Temple", The Saturday Review, 15 October 1910, p. 492

9. "New Headmaster of Repton", The Times, 2 July 1910, p.13

10. Baker and Bell, p. 15

11. "Obituary" – The Archbishop of Canterbury – A Great Spiritual Leader", The Times, 27 October 1944, p. 8

12. Hein, pp. 7–8

13. "Life And Liberty in the Church", The Times, 31 October 1917, p. 3

14. Baker and Bell, p. 16

15. "Today's Cathedral Ceremony", The Manchester Guardian, 5 January 1921, p. 6; and "Bishop Temple Enthroned", The Times, 16 February 1921, p. 12

16. "William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury", The Church Times 3 November 1944. Retrieved 15 December 2019

17. "Dr. Temple Archbishop of York: Eight Notable Years In Manchester", The Manchester Guardian, 1 August 1929, p. 9

18. Baker and Bell, p. 22

19. "Archbishop Temple", The Manchester Guardian, 27 October 1944, p. 6

20. "Archbishop of York: Enthronement in the Minster", The Times, 11 January 1929, p. 7

21. Kynaston, p. 55

22. Grant, Robert. "A Communication: William Temple (1881–1944)", The Sewanee Review, Spring 1945, pp. 288–290 (subscription required)

23. Baker and Bell, p. 35

24. Calder, p. 485

25. Robbins, p. 223

26. "German Atrocities: Aid for Refugees. (Hansard, 23 March 1943)". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 3 April2013.

27. W. Temple papers 51, Temple to Hobhouse, 26 March 1944; also Melanie Barber, "Tales of the Unexpected: Glimpses of Friends in the Archives of Lambeth Palace", Journal of the Friends Historical Society, Vol 61, No.2

28. Lammers, p. 76

29. Bell, p. 539

30. "Death of the Primate", The Times, 27 October 1944, p. 4

31. Robbins, Keith (July 1991). "From Dust to Ashes. The replacement of burial by cremation in England 1840–1967". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 42 (3): 528. doi:10.1017/S0022046900003948.

32. "The Archbishop of Canterbury", The Times, 1 November 1944, p. 4

33. Quoted in Baker and Bell, p. 11

34. Lockhart, pp. 451–454.

35. "William Temple Foundation Archives". John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

Sources

Books

• Baker, A. E.; Bell, George (1946). William Temple and his Message. London: Penguin. OCLC 247149905.

• Bell, George (1935). Randall Davidson: Archbishop of Canterbury, Volume I. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 896112401.

• Calder, Angus (1992). The People's War: Britain 1939-1945. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-7126-5284-1.

• Hein, David (2008). Geoffrey Fisher: Archbishop of Canterbury. Cambridge: James Clarke. ISBN 978-0-227-17295-7.

• Kynaston, David (2008). Austerity Britain 1945–51. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-9923-4.

• Lockhart, J. G. (1949). Cosmo Gordon Lang. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 1033753628.

• Robbins, Keith (1993). History, Religion and Identity in Modern Britain. London: Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-101-9.

Journals

• Lammers, Stephen E (Spring 1991). "William Temple and the Bombing of Germany: An Exploration in the Just War Tradition". The Journal of Religious Ethics Spring. 19 (1): 71–92. JSTOR 40015117. (subscription required)

External links

• Works by William Temple at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about William Temple at Internet Archive

• Archives of William Temple at Lambeth Palace Library

• William Temple at Find a Grave

• Newspaper clippings about William Temple in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW