by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/30/20

Sheikh Abdullah, recently released from jail, manoeuvred into the vacuum created by the flight of the maharaja and his courtiers. With communist help, he organised a militia, some of which was trained and equipped by the Indian army. This was both a defence force should invaders again imperil the Kashmiri capital and a demonstration to all that the old regime of princely autocracy had been swept away. Sheikh Abdullah's supporters flooded the streets of Srinagar, and the city pulsed with political energy. 'The National Conference red flag ... decorates every public building in the city,' the Times of India reported. 'In the main square in the heart of the city, which has been renamed "Red Square", a giant red flag flutters from a tall mast under which workers and ordinary people foregather at all hours of the day to hear the latest news of the war and exchange political gossip.'23

Amid all this turmoil, Sheikh Abdullah received a letter from Freda in England and found the time to write a brief reply from the hotel in Srinagar which had become his temporary headquarters:We are facing a grim struggle and the enemy is almost at our door-step. But we are confident that we shall turn the corner.

I think the best you can do for us at present would be to help us to set up an Information Bureau in New Delhi to work as the medium of our publicity in the outside world. I do not want to call you here because coming here at present is unsafe and unpleasant.

I should love to hear from Bedi. The two of you have done such a lot for us.24

Freda and Bedi took no notice of Sheikh Abdullah's warning to stay clear of Srinagar. Within a few days of their re-assembly as a family in India in December 1947, they all moved on to Kashmir. While the Indian army by then had the upper hand, Kashmir was a war zone. 'From Delhi we were flown in an army troop carrier, Dakota DC5,' Ranga recalls. 'No formal seats, fixed benches along the length of the aircraft and seat belts anchored to the body of the plane. Our great dane Rufus on the floor shivered out of fright all the way. When we landed in Srinagar it was a hive of military activity.' Bedi's role was to work closely with Sheikh Abdullah, both on policy and propaganda. The family were allotted evacuee property -- a simple but well situated house with the name Dar-ul-Aman ('home of peace') at Gagribal, close to Srinagar's renowned Dal Lake.

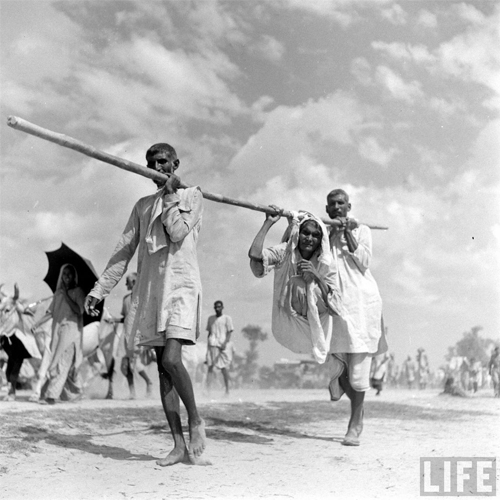

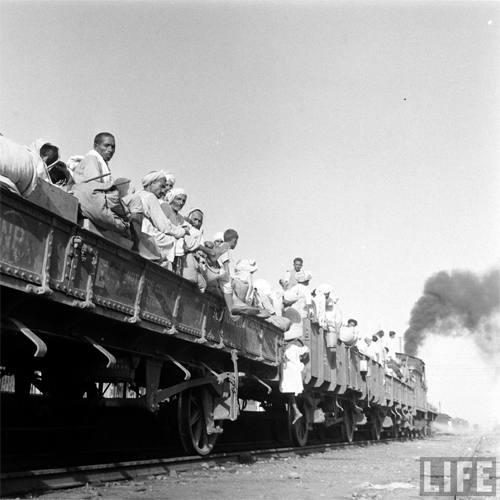

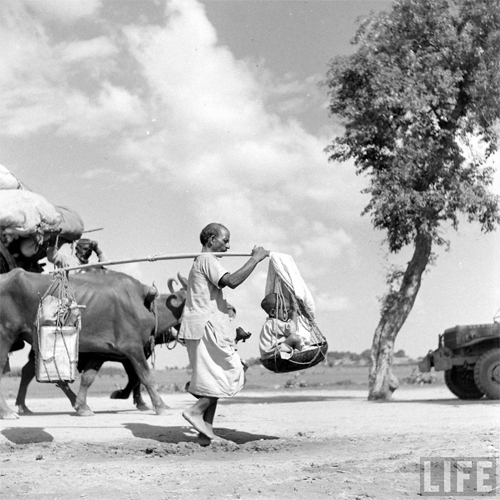

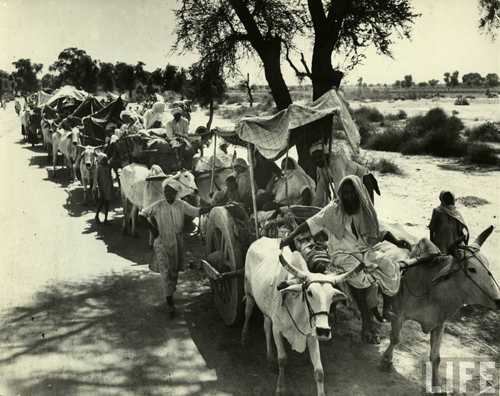

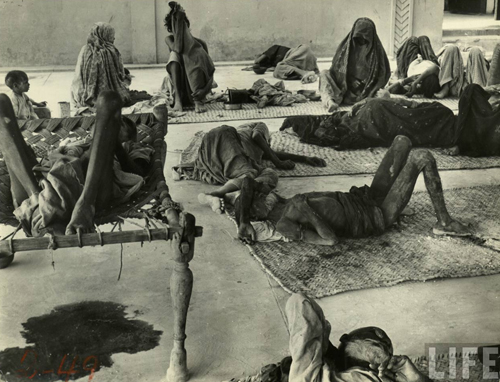

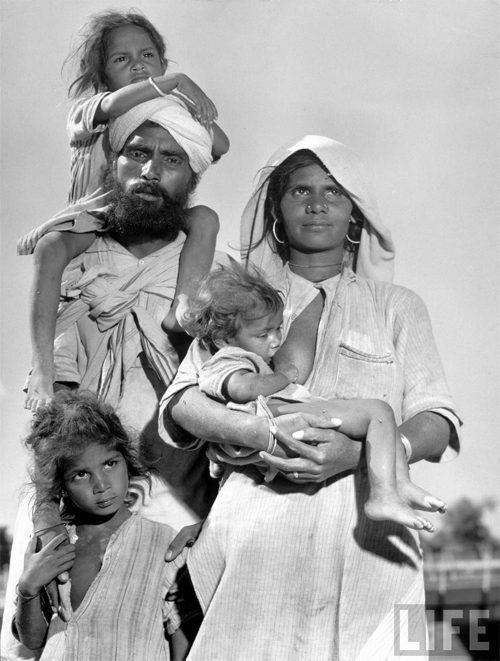

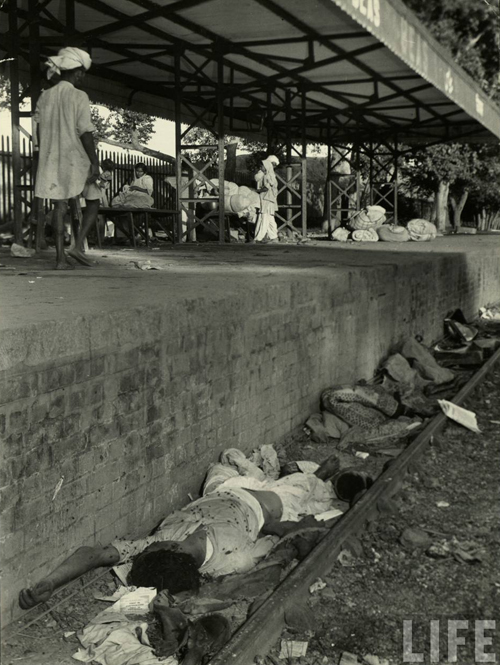

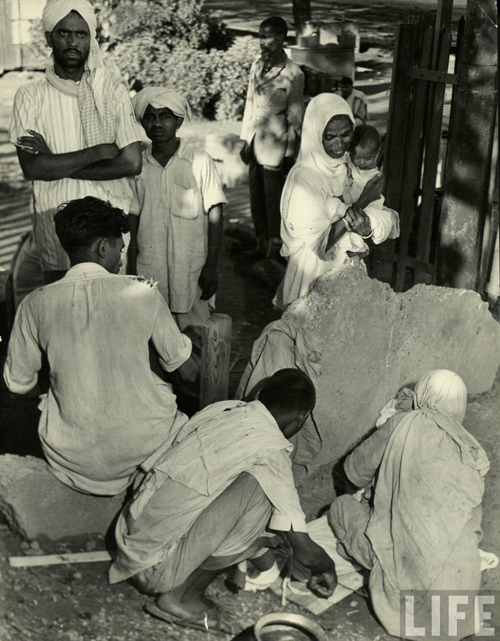

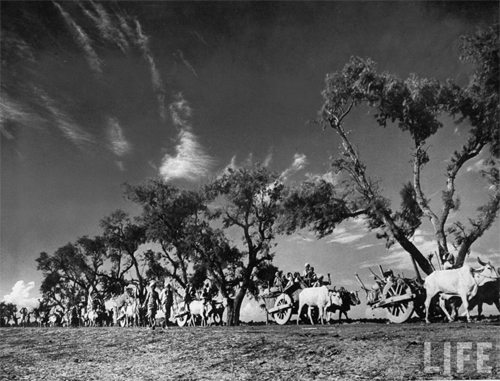

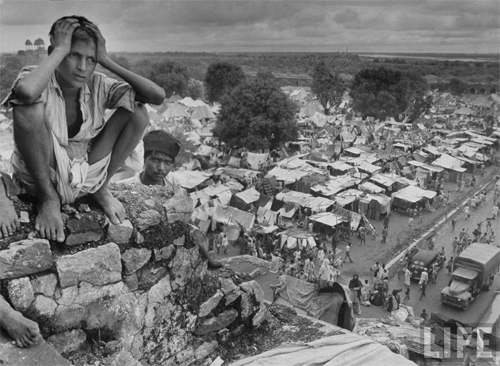

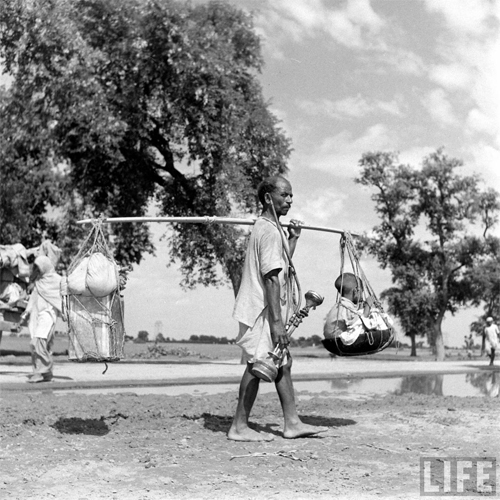

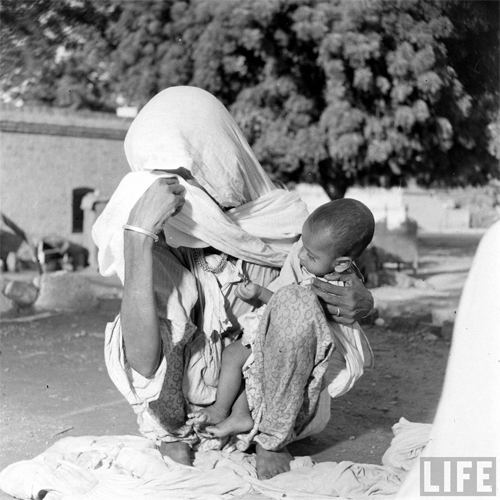

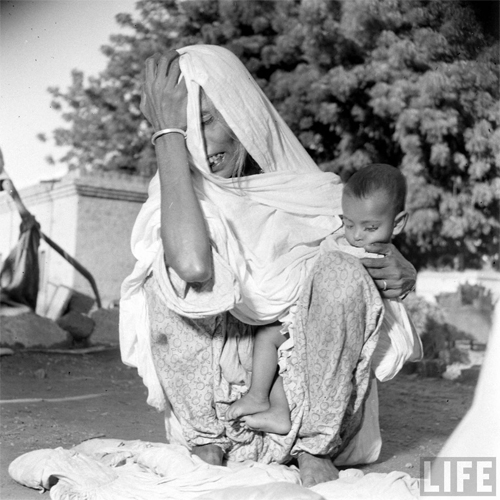

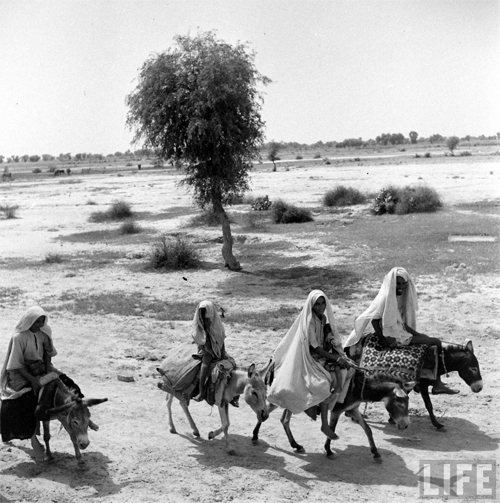

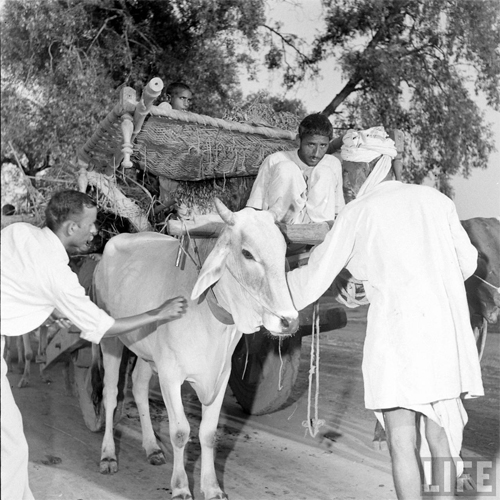

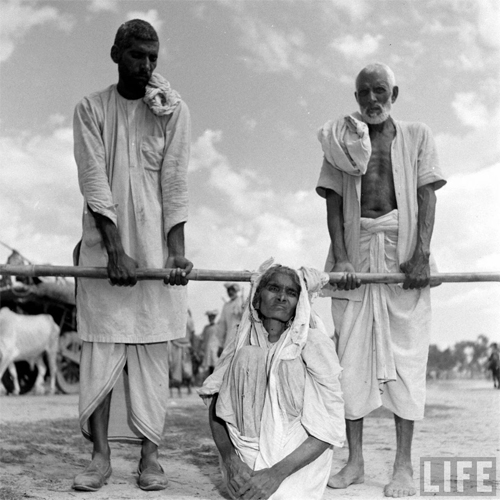

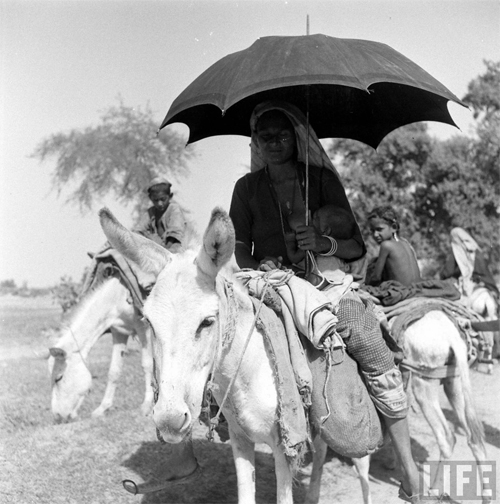

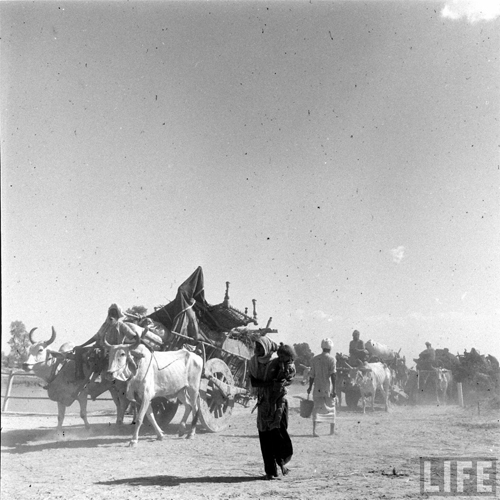

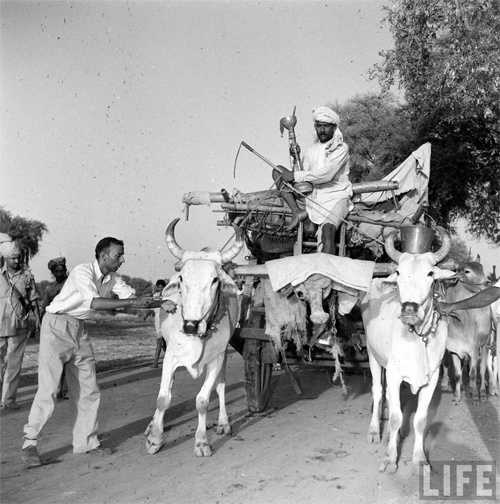

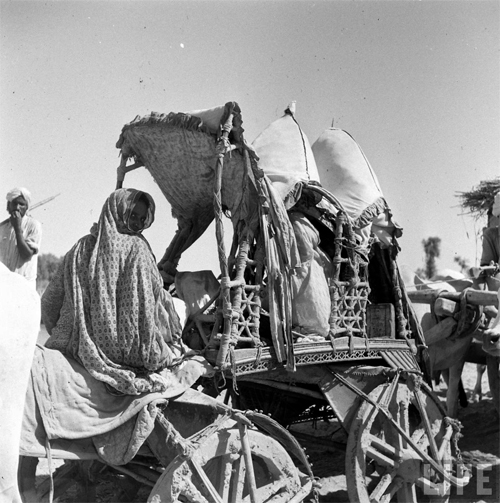

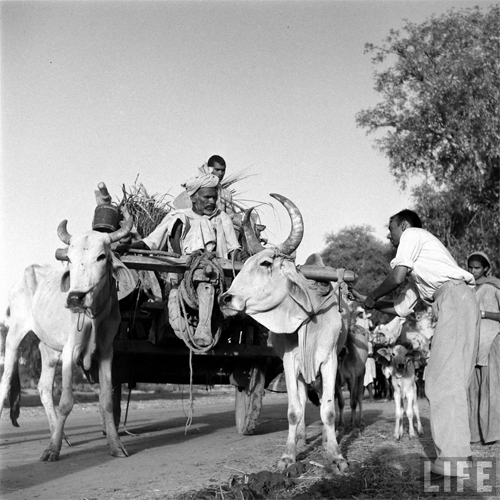

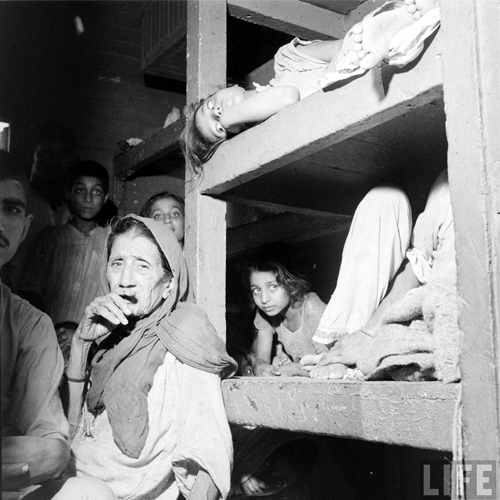

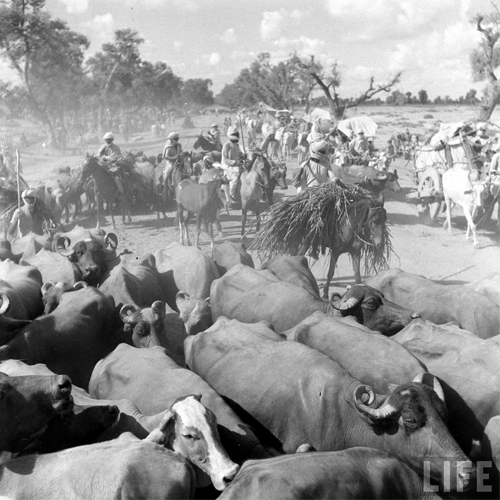

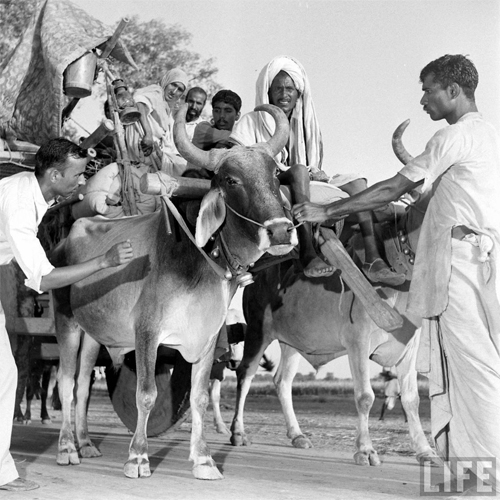

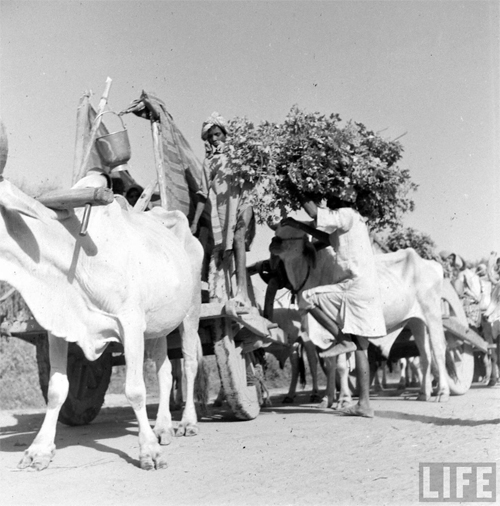

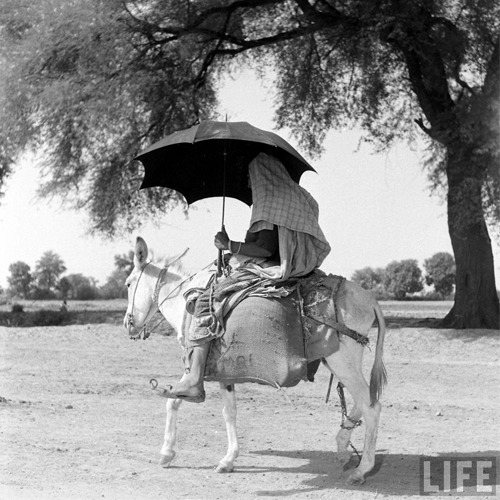

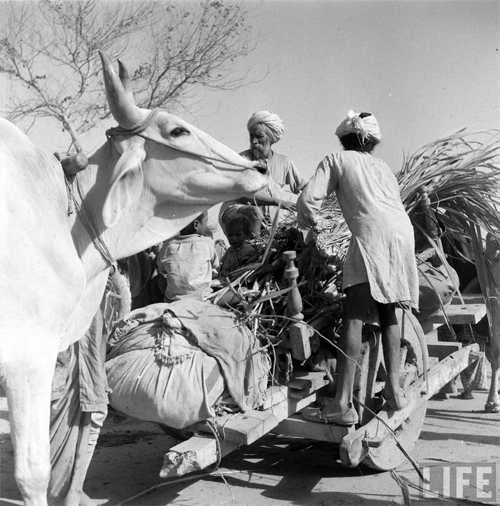

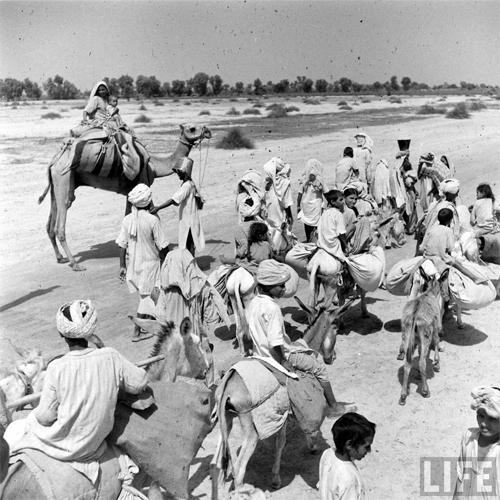

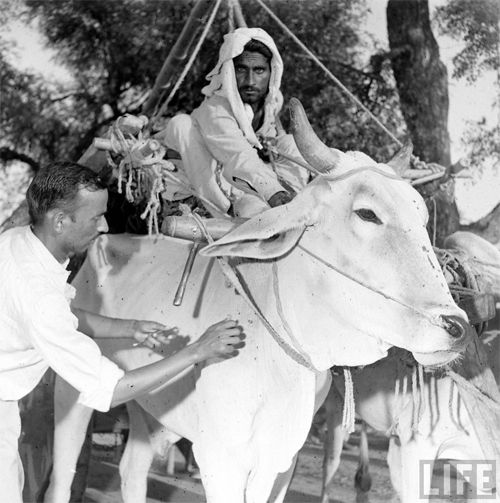

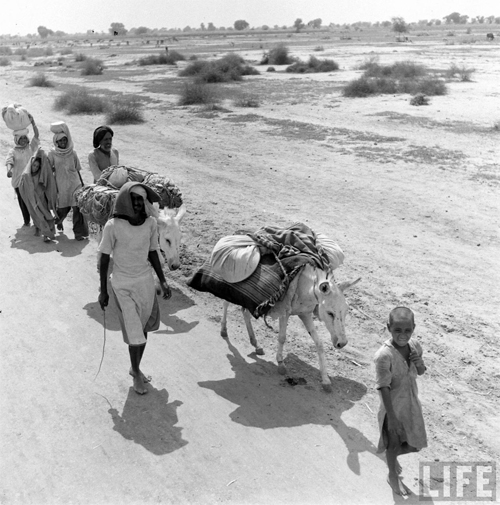

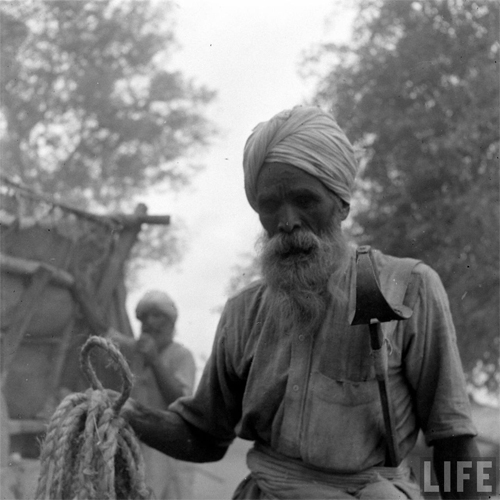

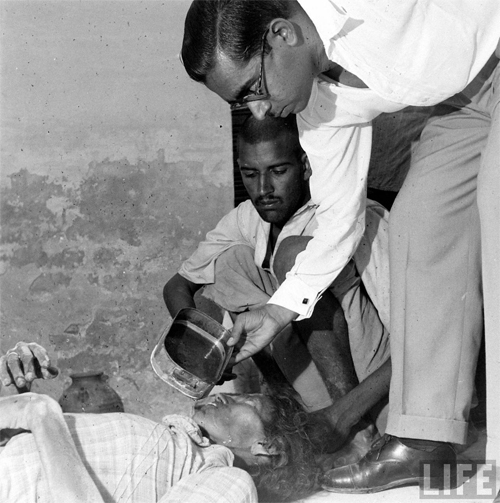

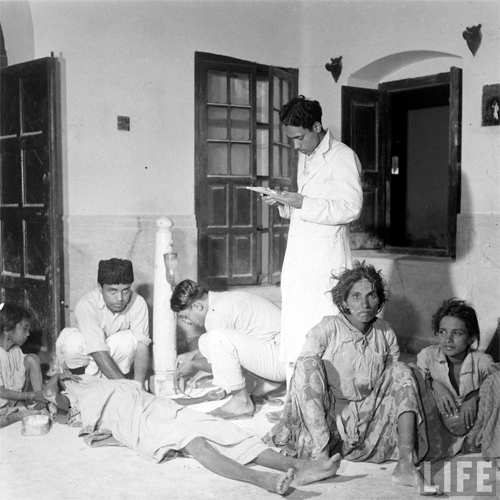

Within days of arriving in Srinagar, the Bedis had a visit from one of the commanding photo-journalists of the era. Margaret Bourke-White had provided Life with its first front cover in 1936. She was a war photographer in Europe but turned her back on the 'decay of Europe' and came to India just as it was about to achieve independence. 'I witnessed that extremely rare event in the history of nations, the birth of twins,' she wrote.25 She arrived in India in March 1946 and spent seven months travelling widely across the subcontinent, meeting and photographing all the main political players. She returned in September 1947, as it became clear that the birth of twin nations, midnight's children, was also a profound human calamity. Her powerful and unsettling images of Partition -- of migration and massacre -- are among her most memorable. She was determined to record India's passage to independence not only in images but in a book, Halfway to Freedom, sub-titled 'a report on the new India' and published in 1949, is a vivid account of India's faltering steps to full nationhood.

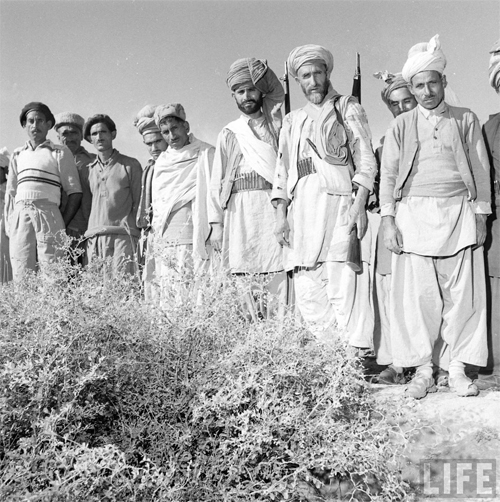

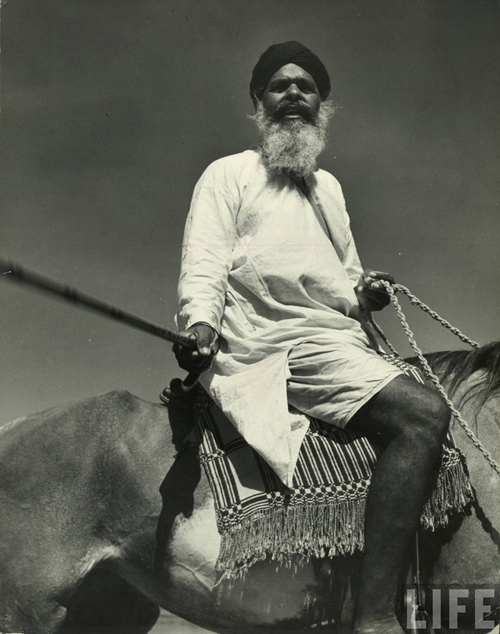

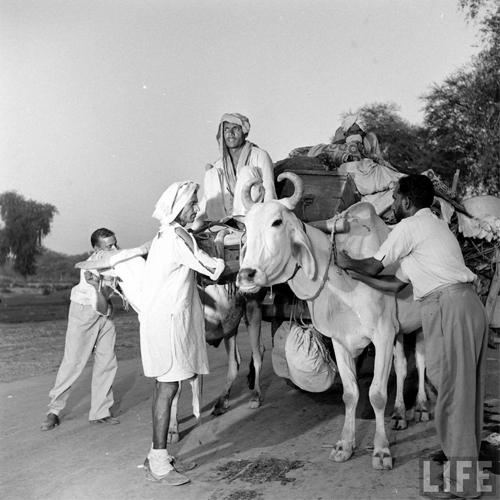

When fighting erupted in Kashmir in late October 1947, Margaret Bourke-White was determined to get there. For a photo-journalist, the prime requirement is to be at the heart of the action -- there's no other way of capturing the most commanding images. Early in November, Sir George Cunningham, the governor of Pakistan's North West Frontier Province, noted in his diary that two American women journalists from Life had been refused permission to go to Abbottabad, the informal headquarters of the invading force, and beyond to Baramulla.26 That didn't stop her. She managed to reach Abbottabad and to meet and photograph a band of several hundred armed Pathans on their way to Kashmir:Unlike higher officials, these tribesmen seemed to know what was going on when I questioned them.

'Are you going into Kashmir?' I asked.

'Why not?' they said. 'We are all Muslims. We are going to help our Muslim brothers in Kashmir.'

Sometimes their help to their brother Muslims was accomplished so quickly that the trucks and buses would come back within a day or two bursting with loot, only to return to Kashmir with more tribesmen, to repeat their indiscriminate 'liberating' -- and terrorizing of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim villager alike.27

A few weeks later, Margaret Bourke-White managed to reach the Kashmir Valley -- approaching not from Pakistani territory but from the Indian side. 'Just before Christmas of 1947 I flew over the wild mountain barrier, with guerrilla warfare going on fiercely but invisible among the ravines and chasms below, and landed in the enchanted city of Srinagar. Everyone who has ever visited Kashmir knows it has a special magic. "It is a different world altogether," my friend Bedi, who was my guide in Kashmir, expressed it; "the water and the land combines into one."'28

The account Bourke-White gave of the turbulence in Kashmir -- the political cohesion of its people, the progressive credentials of the National Conference's manifesto and their 'legendary' leader Sheikh Abdullah, 'this good-natured, weather-beaten, eminently practical and rather homely young man' -- reflect the political outlook of her guide and host. Indeed, her two chapters on Kashmir capture the high water mark of the progressive New Kashmir movement. She interviewed Sheikh Abdullah and several of his associates, met members of his people's militia, and encountered the key figure in the underground movement during the Quit Kashmir campaign. And of course, she got to know Bedi's wife.Freda Bedi is a fair-haired English girl whom Bedi had met and married when both were students at Oxford. She had become deeply interested in the welfare of her adopted country, learned the language, and wore the long full pajama like dress of Kashmiri women. She had her own jail record -- acquired for her participation in the freedom movement -- which is the proud badge of every patriotic Indian who has worked for independence.

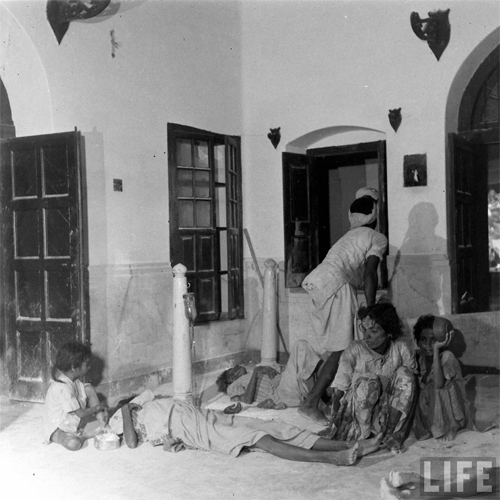

Bourke-White also wanted to see the evidence of the invaders' largely indiscriminate destruction, and having heard about the desecration of a convent at Baramulla and the ransacking of the mission hospital, she persuaded Bedi to take her there:It was badly defaced and littered, and a delegation of students from Srinagar was coming next day to clean it up and salvage what remained of the library .... They would put the Christian mission in as good order as they could in time for Christmas Day.

We made our way into the ravaged chapel, wading through the mass of torn hymnbooks and broken sacred statuary. The altar was deep in rubble. Bedi stooped down over it and picked up one fragment, turning it over carefully in his big hands. It was the broken head of Jesus, with just one eye remaining.

'How beautiful it is,' said Bedi, 'this single eye of Christ looking out so calmly on the world. We shall preserve it always in Kashmir as a permanent reminder of the unity between Indians of all religions which we are trying to achieve.'29

And that's where she left her account of Kashmir -- an impassioned, if partial, piece of reportage. She recited uncritically what she heard from Bedi, and this has to be marked down as one of his key successes as a propagandist. There's hardly a whisper of criticism of Sheikh Abdullah and the movement he headed, and hardly a good word about Pakistan or the invaders acting in its name.

B.P.L. Bedi pops up repeatedly in the pages of Halfway to Freedom as Bourke-White's friend and guide. In Delhi in mid-January 1948 a couple of weeks after leaving Kashmir, she conveniently caught sight of him when attending Gandhi's prayers during a fast to protest against the communal hatred unleashed by Partition. 'Bedi was a giant of a figure in his billowing wool homespun which swept in coarse, oatmeal-colored folds from his massive shoulders to his Gargantuan feet, bare and crusty in their open sandals.'30Another two weeks later, she was again with Bedi in Delhi when she heard of Gandhi's assassination and rushed with her camera to the spot. The following day, Bedi and sixteen-year-old Binder accompanied Bourke-White to Gandhi's cremation, Bedi using his persuasiveness to help get access, and Binder being little short of heroic in guarding the cameras from the crush of the crowd and helping Bourke-White to a vantage point.

Margaret Bourke-White was in her early forties when she arrived in India -- vivacious, sociable, successful, determined and with two failed marriages behind her. She embarked on an affair with one of India's best-known journalists, Frank Moraes -- handsome, hard living, Oxford-educated with an accent to match. He was a friend of the Bedis. He was also married -- and Beryl Moraes, in the throes of a mental health crisis, turned up with her young son Dom at Bourke-White's hotel room to remonstrate. She had other Indian lovers. Her publisher, Peter Jayasinghe, suggested marriage but was rebuffed. For a woman 'who had so little wish to do harm,' says her biographer, 'Margaret left behind her a wide swath of injured wives.'31 Whether Freda was among those who had reason to feel injured, it's difficult to say with certainty. There are stray hints in Bedi's letters at an intimacy. What I really feel like saying to you -- I have told these petals to whisper!' he wrote to Bourke-White in September 1949, just ten days before Freda gave birth to their fourth child.32 That could be a flirtatious aside -- it feels as if it's something more.

B.P.L. Bedi and Margaret Bourke-White seem not to have met again after her departure from India in early 1948, but they kept in touch by letter for almost two decades more. Eight years after Gandhi's assassination, Bedi wrote to his old friend -- that letter hasn't survived, but Bourke-White's tender reply has.It was wonderful to hear from you. Yes I too think of you when the anniversary rolls round of the solemn events in which we shared. And I think of you always, and with quiet affection ....

I was very moved, Bedi dear, at your letter. I too felt we were always very close in understanding and those terrible -- and, in a way, majestic -- events through which we moved, brought us even closer.33

In subsequent years, Bedi offered support and succour through the photo-journalist's diagnosis with Parkinson's disease and her gradual decline in health. 'Remember we who lived through the stormiest of struggles have the deepest faith in the doings of the Divine ... ,' Bedi wrote, reflecting the unorthodox spiritual turn his life had taken. 'I am directed by the Celestial Masters to tell you that your future is greater than your past.'34 Bourke-White wrote respectfully of Bedi's personal journey and fondly of their shared adventures: 'How vividly I remember your long, strong stride on our excursions in Srinagar, Amritsar and Delhi.'35 A few years later, at Bedi's prodding, she wrote in support of funding for a project he had devised to translate and publish Sufi poetry. 'He is one of the most scholarly, cultivated and great-hearted of men.' A generous comment about an old friend she hadn't seen for sixteen years -- and the last act of a loving friendship of which Freda can hardly have been unaware.36

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

Margaret Bourke-White

Bourke-White interviewed on Person to Person, 1955

Born: Margaret White, June 14, 1904, The Bronx, New York City

Died: August 27, 1971 (aged 67), Stamford, Connecticut, US

Nationality: American

Alma mater: Columbia University; University of Michigan; Purdue University; Western Reserve University; Cornell University

Occupation: Photographer, photojournalist

Spouse(s): Everett Chapman (m. 1924; div. 1926); Erskine Caldwell (m. 1939; div. 1942)

Margaret Bourke-White (/ˈbɜːrk/; June 14, 1904 – August 27, 1971) was an American photographer and documentary photographer.[1] She is best known as the first foreign photographer permitted to take pictures of Soviet industry under the Soviet's five-year plan,[2] the first American female war photojournalist, and having one of her photographs (the construction of Fort Peck Dam) on the cover of the first issue of Life magazine.[3] She died of Parkinson's disease about eighteen years after developing symptoms.

Early life

Margaret Bourke-White,[4] born Margaret White[5] in the Bronx, New York,[6] was the daughter of Joseph White, a non-practicing Jew whose father came from Poland, and Minnie Bourke, who was of Irish Catholic descent.[7] She grew up in Bound Brook, New Jersey (in a neighborhood now part of Middlesex), and graduated from Plainfield High School in Union County.[6][8] From her naturalist father, an engineer and inventor, she claimed to have learned perfectionism; from her "resourceful homemaker" mother, she claimed to have developed an unapologetic desire for self-improvement."[9] Her younger brother, Roger Bourke White, became a prominent Cleveland businessman and high-tech industry founder, and her older sister, Ruth White, became well known for her work at the American Bar Association in Chicago, Ill.[7] Roger Bourke White described their parents as "Free thinkers who were intensely interested in advancing themselves and humanity through personal achievement," attributing this quality in part to the success of their children. He was not surprised at his sister Margaret's success, saying "[she] was not unfriendly or aloof".

Margaret's interest in photography began as a hobby in her youth, supported by her father's enthusiasm for cameras.[6] Despite her interest, in 1922, she began studying herpetology at Columbia University, only to have her interest in photography strengthened after studying under Clarence White (no relation).[6] She left after one semester, following the death of her father.[5] She transferred colleges several times, attending the University of Michigan (where she became a member of Alpha Omicron Pi sorority),[10] Purdue University in Indiana, and Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.[5] Bourke-White ultimately graduated from Cornell University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1927, leaving behind a photographic study of the rural campus for the school's newspaper, including photographs of her famed dormitory, Risley Hall.[5][6][11] A year later, she moved from Ithaca, New York, to Cleveland, Ohio, where she started a commercial photography studio and began concentrating on architectural and industrial photography.

In 1924, during her studies, she married Everett Chapman, but the couple divorced two years later.[9] Margaret White added her mother's surname, "Bourke" to her name in 1927 and hyphenated it.[5]

Architectural and commercial photography

One of Bourke-White's clients was Otis Steel Company. Her success was due to her skills with both people and her technique. Her experience at Otis is a good example. As she explains in Portrait of Myself, the Otis security people were reluctant to let her shoot for many reasons.

Firstly, steel making was a defense industry, so they wanted to be sure national security was not endangered. Second, she was a woman, and in those days, people wondered if a woman and her delicate cameras could stand up to the intense heat, hazard, and generally dirty and gritty conditions inside a steel mill. When she finally got permission, technical problems began.

Black-and-white film in that era was sensitive to blue light, not the reds and oranges of hot steel, so she could see the beauty, but the photographs were coming out all black. She solved this problem by bringing along a new style of magnesium flare, which produces white light, and having assistants hold them to light her scenes. Her abilities resulted in some of the best steel factory photographs of that era, which earned her national attention. "To me... industrial forms were all the more beautiful because they were never designed to be beautiful. They had a simplicity of line that came from their direct application of purpose. Industry... had evolved an unconscious beauty – often a hidden beauty that was waiting to be discovered" Margaret Bourke-White, Portrait of Myself (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963), 49.

Photojournalism

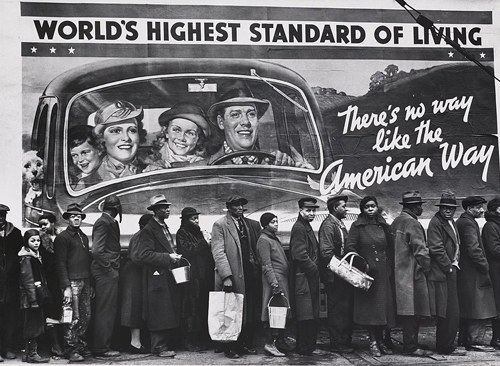

"Kentucky Flood", February 1937

In 1929, Bourke-White accepted a job as associate editor and staff photographer of Fortune magazine, a position she held until 1935.[5] In 1930, she became the first Western photographer allowed to take photographs of Soviet industry.[5]

She was hired by Henry Luce as the first female photojournalist for Life magazine in 1936.[5] She held the title of staff photographer until 1940, but returned from 1941 to 1942,[5] and again in 1945, after which she stayed through her semi-retirement in 1957 (which ended her photography for the magazine)[3] and her full retirement in 1969.[5]

Her photographs of the construction of the Fort Peck Dam were featured in Life's first issue, dated November 23, 1936, including the cover.[12] This cover photograph became such a favorite (see[13]) that it was the 1930s' representative in the United States Postal Service's Celebrate the Century series of commemorative postage stamps. "Although Bourke-White titled the photo, New Deal, Montana: Fort Peck Dam, it is actually a photo of the spillway located three miles east of the dam," according to a United States Army Corps of Engineers web page.[14]

During the mid-1930s, Bourke-White, like Dorothea Lange, photographed drought victims of the Dust Bowl. In the February 15, 1937 issue of Life magazine, her famous photograph of black flood victims standing in front of a sign which declared, "World's Highest Standard of Living", showing a white family, was published. The photograph later would become the basis for the artwork of Curtis Mayfield's 1975 album, There's No Place Like America Today.

Bourke-White and novelist Erskine Caldwell were married from 1939 to their divorce in 1942,[5] and collaborated on You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), a book about conditions in the South during the Great Depression.

She also traveled to Europe to record how Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia were faring under Nazism and how Russia was faring under Communism. While in Russia, she photographed a rare occurrence, Joseph Stalin with a smile, as well as portraits of Stalin's mother and great-aunt when visiting Georgia.

World War II

Bourke-White was the first known female war correspondent[5] and the first woman to be allowed to work in combat zones during World War II. In 1941, she traveled to the Soviet Union just as Germany broke its pact of non-aggression. She was the only foreign photographer in Moscow when German forces invaded. Taking refuge in the U.S. Embassy, she then captured the ensuing firestorms on camera.

As the war progressed, she was attached to the U.S. Army Air Force in North Africa, then to the U.S. Army in Italy and later in Germany. She repeatedly came under fire in Italy in areas of fierce fighting.

"The woman who had been torpedoed in the Mediterranean, strafed by the Luftwaffe, stranded on an Arctic island, bombarded in Moscow, and pulled out of the Chesapeake when her chopper crashed, was known to the Life staff as 'Maggie the Indestructible.'"[3] This incident in the Mediterranean refers to the sinking of the England-Africa bound British troopship SS Strathallan that she recorded in an article, "Women in Lifeboats", in Life, February 22, 1943. She was disliked by General Dwight D Eisenhower but was friendly with his chauffeur/secretary, Irishwoman Kay Summersby, with whom she shared the lifeboat.

In the spring of 1945, she traveled throughout a collapsing Germany with Gen. George S. Patton. She arrived at Buchenwald, the notorious concentration camp, and later said, "Using a camera was almost a relief. It interposed a slight barrier between myself and the horror in front of me." After the war, she produced a book entitled Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly, a project that helped her come to grips with the brutality she had witnessed during and after the war.

The editor of a collection of Bourke-White's photographs wrote: "To many who got in the way of a Bourke-White photograph—and that included not just bureaucrats and functionaries but professional colleagues like assistants, reporters, and other photographers—she was regarded as imperious, calculating, and insensitive."[3]

Korean War

She served as a photographer of Life during Korean War.[15]

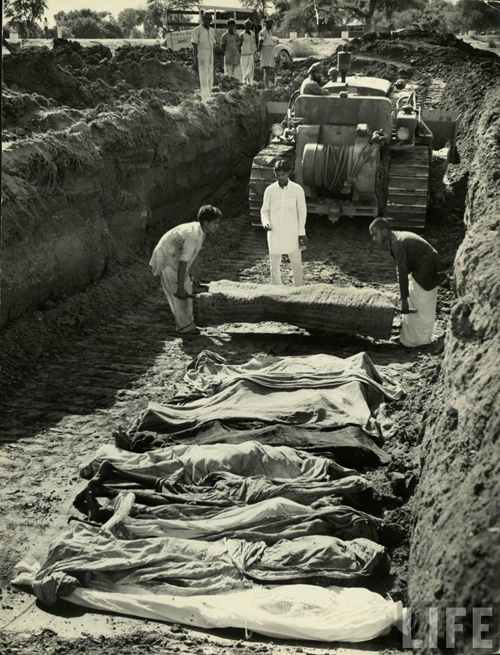

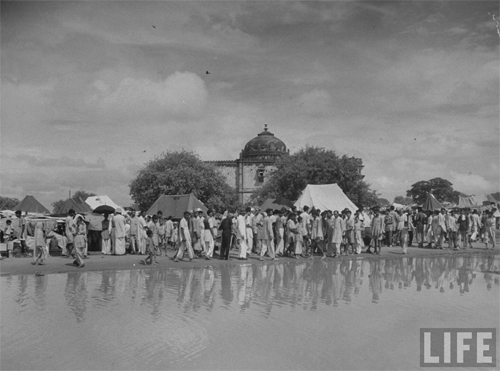

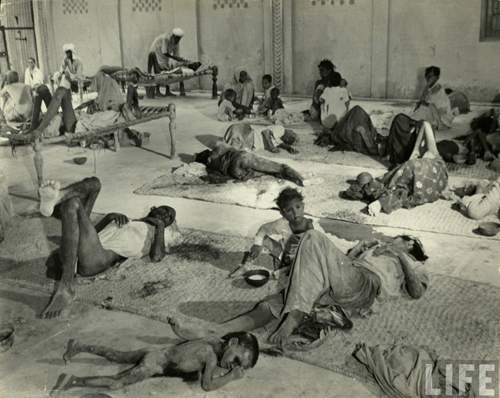

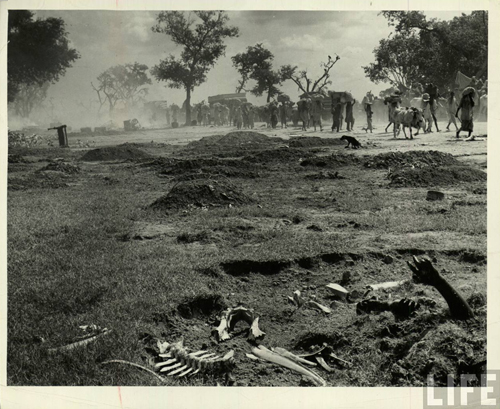

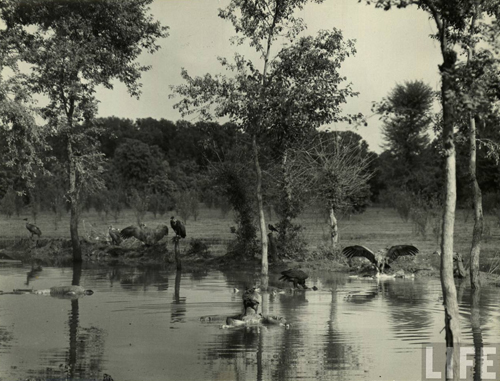

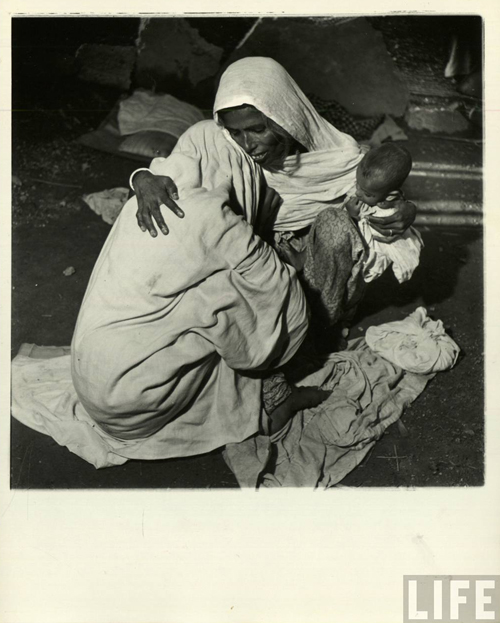

Recording the India–Pakistan partition violence

An iconic photograph that Margaret Bourke-White took of Mohandas K. Gandhi in 1946

Bourke-White is known equally well in both India and Pakistan for her photographs of Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar at his home Rajgriha, Dadar in Mumbai on the occasion of a third impression of his book which was published in December 1940 as Thoughts on Pakistan (the book was republished in 1946 under the title India's Political What's What: Pakistan or Partition of India). These photographs were published on LIFE magazine cover. She also photographed M. K. Gandhi at his spinning wheel and Pakistan's founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, upright in a chair.[16][17]

She also was "one of the most effective chroniclers" of the violence that erupted at the independence and partition of India and Pakistan, according to Somini Sengupta, who calls her photographs of the episode "gut-wrenching, and staring at them, you glimpse the photographer's undaunted desire to stare down horror." She recorded streets littered with corpses, dead victims with open eyes, and refugees with vacant eyes. "Bourke-White's photographs seem to scream on the page," Sengupta wrote. The photographs were taken just two years after those Bourke-White took of the newly captured Buchenwald.[16]

Sixty-six of Bourke-White's photographs of the partition violence were included in a 2006 reissue of Khushwant Singh's 1956 novel about the disruption, Train to Pakistan. In connection with the reissue, many of the photographs in the book were displayed at "the posh shopping center Khan Market" in Delhi, India. "More astonishing than the images blown up large as life was the number of shoppers who seemed not to register them," Sengupta wrote. No memorial to the partition victims exists in India, according to Pramod Kapoor, head of Roli, the Indian publishing house coming out with the new book.[16]

She had a knack for being at the right place at the right time: she interviewed and photographed Mohandas K. Gandhi just a few hours before his assassination in 1948.[18] Alfred Eisenstaedt, her friend and colleague, said one of her strengths was that there was no assignment and no picture that was unimportant to her. She also started the first photography laboratory at Life magazine.[9]

Later years and death

In 1953, Bourke-White developed her first symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[5] She was forced to slow her career to fight encroaching paralysis.[3] In 1959 and 1961, she underwent several operations to treat her condition,[5] which effectively ended her tremors but affected her speech.[3] In 1971, she died at Stamford Hospital in Stamford, Connecticut, aged 67, from Parkinson's disease.[4][5][19]

Bourke-White wrote an autobiography, Portrait of Myself, which was published in 1963 and became a bestseller, but she grew increasingly infirm and isolated in her home in Darien, Connecticut. In her living room, there "was wallpapered in one huge, floor-to-ceiling, perfectly-stitched-together black-and-white photograph of an evergreen forest that she had shot in Czechoslovakia in 1938". A pension plan set up in the 1950s, "though generous for that time", no longer covered her health-care costs. She also suffered financially from her personal generosity and "less-than-responsible attendant care."[3]

Legacy

Bourke-White's photographs are in the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the New Mexico Museum of Art[20] and the Museum of Modern Art in New York as well as in the collection of the Library of Congress.[9] A 160-foot-long photomural she created for NBC in 1933, for the Rotunda in the broadcaster's Rockefeller Center headquarters, was destroyed in the 1950s. In 2014, when the Rotunda and Grand Staircase leading up to it were rebuilt, the photomural was faithfully recreated in digital form on the 360-degree LED screens on the Rotunda's walls. It forms one of the stops on the NBC Studio Tour.

Many of her manuscripts, memorabilia, photographs, and negatives are housed in Syracuse University's Bird Library Special Collections section.

Principal exhibitions

Group

• John Becker Gallery, New York: 1931 (Photographs by Three Americans, with Ralph Steiner and Walker Evans)

• Museum of Modern Art, New York:1949 (Six Women Photographers, 1951 (Memorable Life Photographs))[21]

Individual

• Annual Exhibition of Advertising Art, New York: 1931 (with Anton Bruehl; art works by others)

• Little Carnegie Playhouse, New York: 1932

• Rockefeller Center, New York: 1932

• Art Institute of Chicago: 1956

• Syracuse University, NY: 1966

• Carl Siembab Gallery, Boston: 1971

• Witkin Gallery, New York: 1971

• Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca: 1972 (retrospective)[21]

Public collections

• Brooklyn Museum

• Cleveland Museum of Art

• Library of Congress

• Museum of Modern Art, New York City

• New Mexico Museum of Art

• Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[22]

Portrayals in popular culture

Bourke-White was portrayed by Farrah Fawcett in the television movie, Double Exposure: The Story of Margaret Bourke-White (1989) and by Candice Bergen in the 1982 film Gandhi.

Awards

• honorary Doctorate: Rutgers University, 1948[5]

• honorary Doctorate: University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), 1951[5]

• Achievement Award: US Camera, 1963[5]

• Honor Roll Award: American Society of Magazine Photographers, 1964[5]

In 1990, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[23] She was designated a Women's History Month Honoree in 1992 and again in 1994 by the National Women's History Project.[24]

Publications

• Eyes on Russia (1931)

• You Have Seen Their Faces (1937; with Erskine Caldwell) ISBN 0-8203-1692-X

• North of the Danube (1939; with Erskine Caldwell) ISBN 0-306-70877-9

• Shooting the Russian War (1942)

• They Called it "Purple Heart Valley" (1944)

• Halfway to Freedom; a report on the new India (1949)

• Interview with India,(1950)

• Portrait of Myself. Simon Schuster. (1963). ISBN 0-671-59434-6

• Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly (1946)

• The Taste of War (selections from her writings edited by Jonathon Silverman) ISBN 0-7126-1030-8

• Say, Is This the USA? (Republished 1977) ISBN 0-306-77434-8

• The Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White ISBN 0-517-16603-8

Biographies and collections of Bourke-White's photographs

• Margaret Bourke-White: Photography of Design, 1927–1936 ISBN 0-8478-2505-1

• Margaret Bourke-White ISBN 0-8109-4381-6

• Margaret Bourke-White: Photographer ISBN 0-8212-2490-5

• Margaret Bourke-White: Adventurous Photographer ISBN 0-531-12405-3

• Power and Paper, Margaret Bourke-White: Modernity and the Documentary Mode ISBN 1-881450-09-0

• Margaret Bourke-White: A Biography by Vickie Goldberg (Harper & Row: 1986) ISBN 0-06-015513-2

• Bourke-White: A Retrospective, Collected and Circulated by the International Center of Photography, New York. Exhibition catalog United Technologies Corporation, 1988

• Margaret Bourke-White: Twenty Parachutes, Nazraeli Press, 2002 ISBN 1-59005-013-4

• Margaret Bourke-White: The Early Work, 1922–1930 Selected, with an essay by Ronald E. Ostman and Harry Littel (David E Godine 2005) ISBN 9781567922998

• For the World to See: The Life of Margaret Bourke-White by Jonathan Silverman ISBN 0-670-32356-X

• Down North: John Buchan and Margaret Bourke-White on the Mackenzie by John Brinckman ISBN 978-0-9879163-3-4

• Witness to Life and Freedom: Margaret Bourke-White in India & Pakistan by Pramod Kapoor (Roli & Janssen 2010) ISBN 9788174366993

In popular culture

Fictional character based on Margaret Bourke-White on-screen.[25]

• Megan Fox in South Korean movie The Battle of Jangsari

References

1. Hudson, Berkley (2009). Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE. pp. 1060–67. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

2. Benton, Whisenhunt, William; E., Saul, Norman. New perspectives on Russian-American relations. p. 193. ISBN 9781138916234. OCLC 918941221. This was the first time a professional photographer from abroad had been allowed to take pictures of the "Piatiletl" (Five-year plan).

3. Callahan, Sean. "The Last Days of a Legend". Scout Productions. Bullfinch Press. Archived from the originalon December 13, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

4. "ULAN Full Record Display – Bourke-White, Margaret". Union List of Artist Names – Getty Research. The J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

5. Gaze, Delia, ed. (1997). Dictionary of Artists, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. p. 1512. ISBN 9781884964213.

6. "The Industrial revelations of Margaret Bourke-White". USA Today, the Society for the Advancement of Education. April 2005. Retrieved June 5, 2010. A native of the Bronx, NY, Margaret Bourke-White (1904–71) first gained recognition as an industrial photographer based in Cleveland

7. Roger Bourke White. "Roger White's Autobiography". Retrieved June 2, 2010.

8. "She grew up in Bound Brook, NJ, and graduated from Plainfield High School". Archived from the original on September 12, 2006. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

9. "Margaret Bourke-White". Gallery M. Retrieved July 2,2006.

10. "Greek Life NPC Alpha Omicron Pi". Student Affairs. East Carolina University. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

11. Bourke-White, Margaret; Ronald Elroy Ostman; Harry Littell (2005). Margaret Bourke-White: the early work, 1922–1930. David R. Godine Publisher. p. 88. ISBN 9781567922998.

12. "1930s source:life fort peck dam margaret bourke white – Google Search". Google.

13. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

14. [1] Web page for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Office of History. Retrieved July 2, 2006. Archived April 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

15. LIFE in Korea: Rare and Classic Photos From the 'Forgotten War'

16. Sengupta, Somini, "Bearing Steady Witness To Partition's Wounds," an article in the Arts section, The New York Times, September 21, 2006, pages E1, E7

17. Kapoor, Pramod (2010). Witness to Life and Freedom : Margaret Bourke-white in India & Pakistan. New Delhi: Lustre Press, Roli Books. ISBN 978-81-7436-699-3.

18. Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 225–233.

19. Whitman, Alden (August 28, 1971). "Margaret Bourke-White, Photo-Journalist, Dead at 67". The New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2010. Margaret Bourke-White, one of the world's pre-eminent photographers, died yesterday morning at the Stamford (Conn.) Hospital from complications after a long battle with Parkinson's disease, a nerve disorder. She was 67 years old and lived in Darien, Conn.

20. "Margaret Bourke-White". New Mexico Museum of Art. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

21. "Bourke-White, Margaret". Dictionary of Women Artists. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. 1997.

22. "Search". Rijksmuseum.nl.

23. "Bourke-White, Margaret". National Women's Hall of Fame.

24. "Honorees: 2010 National Women's History Month". Women's History Month. National Women's History Project. 2010. Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

25. '장사리' 메간 폭스 출연에 숨겨진 사연은? [★비하인드

External links

• Margaret Bourke-White Papers at Syracuse University

• Images from Time's image archive by Margaret Bourke-White.

• Margaret Bourke-White in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art

• Women in History: Margaret Bourke-White

• Distinguished Women: Margaret Bourke-White

• Margaret Bourke-White Photographs

• Masters of Photography: Margaret Bourke-White

• Margaret Bourke-White in cosmopolis.ch

• Margaret Bourke-White at Find a Grave