by Paul G. Hackett

[Excerpted with revisions from: Paul G. Hackett, Barbarian Lands: Theos Bernard, Tibet, and the American Religious Life. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 2008.]

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

British-Indian intelligence reported that Kalimpong had an “extensive spy-network” by 1946 (SAWB, IB 1946, 4). We will probably never know about all the spies who operated in Kalimpong, but arguably the two most famous who appeared in Kalimpong were Gergan Dorje Tharchin, the editor of the Tibet Mirror, and Hisao Kimura, the “Japanese agent who disguised himself as a Mongolian pilgrim [… and] was recruited by the British Intelligence to gather information on the Chinese in Eastern Tibet” (Kimura 1990, book jacket). Tharchin had settled in Kalimpong and started his newspaper; with that he became of interest to the British, and also the Chinese, who tried to buy him.

-- Kalimpong: The China Connection, by Prem Poddar and Lisa Lindkvist Zhang

Like Tashkent a thousand years earlier, Kalimpong of the twentieth century was one of those cultural junctures — the meeting place of age-old civilizations and a crossing over point between radically different worlds. Below and to the south lay the jungles and lowlands of British India and most prominently of all, Calcutta, where hill-stations such as Kalimpong met their commercial port, where the whole population of India — Lepchas, Nepalis, Bengalis, British, Chinese, Malaysians and a whole host of traders, missionaries, soldiers and bureaucrats — daily swarmed over each other in pursuit of their lofty and not-so-lofty goals. Above and to the north lay the mountain ranges of Tibet, a kingdom like no other, perched atop the high Himalayas, a monastic haven far above the mundane world below, a place that six million people called “home”; from the narrow valleys of Ladakh and Guge near Kaśmir in the west, to the wide open plains of Amdo and the Chang-tang on the border of China to the east, Tibet was an ethereal, 1.2 million square kilometer land-mass whose natural borders were visible from space. Kalimpong was where these two worlds met.

Called “Da-ling Kote” by the local Bhutias after the old fort on the 4,000 ft. ridge line, for most of its pre-history, Kalimpong was little more than the stockade (“pong”) of a Bhutanese minister (“Kalön”). It was only with the annexation of the area by the British in the late-19th century with the hopes of opening trade routes did the small village formed around the ruins of the old fort begin to grow. In the wake of the 1904 Younghusband invasion of Tibet, Kalimpong took on greater significance as trading post as the wool trade shifted markets from the administrative capital of the region, Darjeeling, to its new economic capital, Kalimpong, being slightly closer the Tibetan passes of Jelep-la and Nathu-la, with easy transport south to Calcutta for shipping to the textile mills of England and eventually, America.

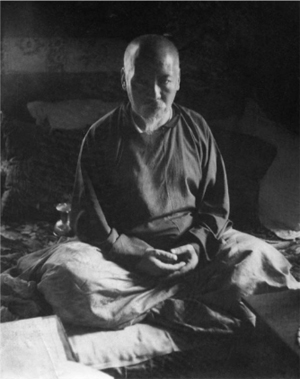

Though still in many aspects a trading post and missionary enclave, by the early twentieth century Kalimpong had much to offer a Tibetophile. Most notably, Kalimpong was home to the only Tibetan language newspaper in the world, The Mirror or “Me-long,” as it was known in Tibetan. It was also home to the newspaper’s editor and the de facto center of the Tibetan ex-patriot community in Kalimpong, Dorje Tharchin, known affectionately to all and sundry as Tharchin Babu.

Tharchin was a unique man. Born in 1890 in the village of Pu (spu) in the Khunu region of Spiti (spi ti), Tharchin was the son of one of only a handful of Moravian Christian converts in the western Tibetan borderlands of Spiti, and had spent the early years of his life in Khunu being educated in missionary schools (taught in a mixture of Tibetan and Urdu). With the death of his parents in the early years of the century, Tharchin finally left his village at the age of twenty. During the years that followed, Tharchin earned money as a common laborer spending his time between Delhi and the British “summer capital” of Simla at the mouth of the Kulu valley, and by the late 1910’s Tharchin was fully ensconced in his identity as a Christian and could often be found preaching in one of the cities’ local bazaars.

Accepting a job at the Ghoom Mission School outside of Darjeeling, Tharchin taught Tibetan and Hindi at a Christian school belonging to the Scandanavian Alliance Mission.

By 1917, Tharchin had managed to secure a Government scholarship to attend school and so relocated himself to Kalimpong to enter into the “Teacher Training” program being operated by the Scottish Union Mission [Scottish Universities' Mission? [SUM?]].

The Scottish Universities' Mission Institution (S.U.M.I. or S.U.M.Institution) of Kalimpong, West Bengal has completed hundred and twenty five years of its glorious existence in 2011 and the contribution it has been rendering to the spread of education in the hills of Darjeeling and for that matter the whole of North East India, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim and a large part of Bengal is prodigious and laudable.

SUMI it light from which torches of knowledge could spread to the corners of this region to enlighten the darkness of illiteracy. The institution was uniquely endowed with a rare gift of overseas missionaries representing the Church of Scotland whose abiding contribution to the spread of education is worth remembering.

The Treaty of Sugauli 1816 between Nepal and East India Company granted Sikkim the region West of the Teesta under the guarantee of the Company. This territory was put under Capt. Lloyd and Mr. J. Grant, Commissioner Resident at Malda. Captain Lloyd toured the region and saw the suitability of Darjeeling as a sanitarium. He strongly urged the then Governor General Lord Bentinck to acquire it for health, trade, military and political purposes. Lord Bentinck agreed and negotiations with Sikkim Raja were made. In 1835 the Sikkim Raja made a free gift of Darjeeling Hill. In 1841 compensation of Rs. 3000 per annum was made to the Raja which was raised to Rs. 6000 per annum. By 1840 a road was made from Pankhabari to Darjeeling. Houses were built in the wooded hill slopes. In 1839, Dr. [Archibald] Campbell was appointed Superintendent of Darjeeling. Between 1839-42 a cart road had been built between Siliguri and Darjeeling. In the neighborhood tea plantation had begun. By 1850 there was a bazaar, a jail and a hospital. In 1840, the famous botanist Sir Joseph Hooker and Dr. Campbell while touring in North Sikkim were seized and imprisoned for six weeks. An avenging force was sent to Sikkim. The result was that the land south of the Rangeet and Tarai were annexed and formed the western part of the district of Darjeeling.

Disputes on the borders of Bhutan and Bengal had continued for years since the British came to power in Bengal and Assam. In 1863 Sir Ashley Eden was sent to negotiate a treaty with Bhutan. The mission was a failure. He was ill-treated in Bhutan and in retaliation Indian forces invaded Bhutan from the south. Tongsa, Penlop signed a treaty with Indian Government in 1865. By this treaty Bhutan ceded the Duars and the region between the Jaldhaka and the Teesta, the present Kalimpong Sub-Division. Thus the regions ceded by Sikkim and Bhutan formed the Darjeeling District. In this district, came the first missionary of the Church of Scotland in 1870.

The first Church of Scotland missionary Rev. William Macfarlane came to Darjeeling from Gaya in 1870. He bought a small piece of land and built a small school in Darjeeling. Boys attended this school and received education for four years. These youths were sent to schools in the neighboring tea gardens and villages. He himself toiled hard at school and toured Sikkim and the neighborhood. In 1873, he crossed the Teesta and reached Kalimpong. He thought that Kalimpong would be a fruitful station for education and evangelism. In 1873, he came to Kalimpong, bringing two teachers with him and opened a small school – the first school in Kalimpong.

The teaching and preaching work in Darjeeling prospered. Many youths became workers in offices, teachers in schools and some of them were baptized in 1874. These young Christians became leaders of Church – Ganga Prasad Pradhan, Lakshmansing Mukhia, Surjaman Mukhia, Apun Laksom, Jangabir Mukhia and Sukhman Limbu.

The area of Rev. Macfarlane’s work was so extensive by 1878 that he could not cover the area alone. So he sent a letter to Scotland, asking for two workers. So the Church of Scotland in 1880 sent two missionaries – Rev. W.S. Sutherland and Rev. A. Turnbull to work in the newly founded educational and religious work. The three missionaries in a meeting agreed to work in different parts of Darjeeling District and Sikkim – Turnbull in Darjeeling, Sutherland in Sikkim and Macfarlane in Kalimpong.

During the furlough in 1881 after 15 years, Rev. Macfarlane visited churches in Scotland and held meetings in which he told them about the work of the missionaries in the Eastern Himalaya. The Church of Scotland was very happy to hear this. A Missionary Association of four Scottish Universities had been formed a few years before this. Mr. Macfarlane met this Scottish Universities Mission Association members and had talks about the teaching and preaching work of the missionaries. This Scottish Universities Mission, under and jointly with Church of Scotland decided to send Mr. Macfarlane in the Eastern Himalayan region. This S.U.M. field of work was to be Sikkim. It was decided to open a Training school for teachers and catechists in Kalimpong, so Mr. Macfarlane returned to Kalimpong as the first S.U.M. missionary. Meanwhile, Rev. Sutherland was working in Kalimpong and in 1886 on 19th April, Training Institution was opened with twelve students. The number of pupils gradually grew and the mission had to provide accommodation for students.

Mr. Macfarlane began his activity of the construction of houses – School, hostel for students and quarters for teachers. These were low roofed one storied long houses. The hostel consisted of a long one storied house divided into separate rooms. Each room was occupied by two or three students. They cooked their food in the room. He supervised the construction of the houses, brought materials and went to the forest to employ woodcutters and sawyers for timber in the construction of houses. On 15th February 1887, he had gone to the forest to bring timber, he returned late in the evening tired and went to bed early. Next Morning, his servant found him dead. He was 47 years of age at his home call.

Now, the burden of the Guild Mission and Scottish University Mission work fell on the shoulders of Rev. Sutherland. To relieve him of the two responsibilities, the Young Men’s Guild sent Rev. J.A. [John Anderson] Graham who took the church work in Kalimpong. Rev. W.S. Sutherland was put in charge of the S.U.M. Training Institution. He built the Lalkothi – Ladies’ Mission House. He as the first Principal of the S.U.M. Training Institution worked up to 1889. In 1891, an English School was opened by Shri Harkadhoj Pradhan near the bazaar. He taught the young men who later on held good jobs in the court and forest and police departments. After 12 or 13 years, this school was amalgamated with the Training Institution. Rev. Sutherland returned after 20 years in this district to Scotland. Rev. John Macara worked in his place from 1900 to 1902. Then Rev. T.E. Taylor succeeded him in the same year.

He was a humble selfless Christian. During his tenure of Principal ship, he did manual labour leading the students. He and the training students after hard labour drained a large pool of water which covered the low area between the Girls’ hostel and K.D. Pradhan Road. This is now the Mission ground.

In 1904 – 05, the training Institution was shifted to its present location. The one storied school and hostel were taken over by Women’s Guild Mission. The new double storied building had then a Constance Taylor Memorial Hall and class rooms on both sides on the ground floor. The upper stories contained sleeping rooms for boarders. Rev. Taylor died on Christmas Day 1906 at Newpara, Gorubathan where he had gone to nurse a tea planter. Rev. W.G. McKean became the Principal after Rev. T.E. Taylor and served up to 1907 when the Rev. W.S. Sutherland returned to Kalimpong. He served this term of 14 years up to January 1921. Aberdeen University had conferred D.D. on him while he was in Scotland. Although, this are between the Jaldhaka and the Teesta was annexed to Bengal by the Treaty of Sinchula in 1865, there were few people and land survey was taken lately. Mr. C.A. Bell (Later Sir) the second Settlement Officer undertook the first survey of this sub-division in 1901-03. The land was classified (a) Khas mahal, (b) Forest and (c) Tea or Cinchona plantation.

The Church of Scotland within 30 years, by the end of the last century, had opened Primary Schools in Darjeeling and Kalimpong. In Kalimpong Female Education and Home Industries and a hospital were begun. In these institutes local people were trained.

In the hospital opened in 1893, Scottish Missionary doctors and sisters but they needed nurses, compounders and attendants. So, young men and women were taken in the hospital to be trained in this profession. The Hospital Superintendent in the early years of this century, selected labourious, intelligent, patient youths and gave them thorough practical and theoretical coaching. After 3 years they were sent to Patna Medical School for the completion of the course. These young men after completion of course became L.M.S. The first qualified doctors came from S.U.M.I. where they educated first. Similarly, nurse training started here in 1913 and this Nurses Training is going on. So Indirectly the students of this institution have served their community as doctors. These were the first doctors from this district – Yensing Sitling, Ongden Rongong, Prem Tshring Rongong, Lemsing Foning, Bishnulal Diskhit, Tongyuk Chhiring and Kashinath Chettri.

At the arrival of Dr. Sutherland in 1907 as the Principal of the S.U.M.I. The Institution had developed into a large school with over 800 students. There were his assistants David Lepcha, A. Ropcha Sada, Singbir Pradhan, Bahadur Lama, Lakshmansingh Mukhia, Kiran Sarkar, Dharnidhar Biswas, Benjamin Roy.

The Teacher’s Training School was started in 1908. This department took teachers of primary schools and gave practical and theoretical lessons in classes. The teachers who had read up to Upper Primary Class were put in Lower Grade and those above and class four in Higher Grade Class. Gradually all teachers of Primary Mission Schools were sent to Kalimpong S.U.M.I. for refresher.

-- About Us, by Scottish Universities' Mission Institution

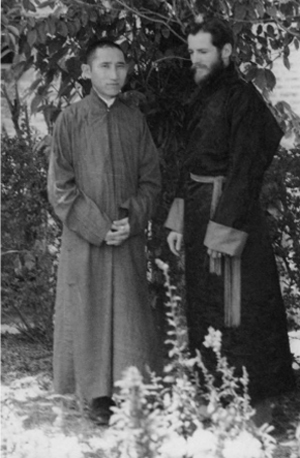

Having recently published two small Tibetan language primers, a Tibetan Primer with Simple Rules of Correct Spelling and The Tibetan Second Book, his knowledge of Tibetan brought him to the notice of W.S. Sutherland, a missionary who had spent the better part of forty years in the area of Kalimpong running a combination orphanage and missionary school, who quickly put Tharchin to work teaching Tibetan to a mixture of Bhutia and Tibetan boys in the orphanage.

Despite all these activities and events, Tharchin continued his proselytizing throughout Sikkim, as well as serving as a Tibetan translator for embassies to Bhutan and Sikkim. It was during this time, as well, that Tharchin began to forge friendships with many of the high ranking Tibetan and British dignitaries who passed through the region on a regular basis and various current and future members of the Tibetan government, and relatives of the various aristocratic houses. In the midst of these activities he commenced work on what would be his greatest achievement, eventually earning him worldwide notoriety.

It was on one occasion, in August of 1925 while working for Sutherland’s successor at the Scottish Union Mission [Scottish Universities' Mission? [SUM?]], John [Anderson] Graham, that Tharchin noticed “a Roneo Duplicator lying idle in the office of Dr. [John Anderson] Graham” and asked him if he could take it, thinking to produce his own newspaper in Tibetan. Graham offered it to Tharchin, though offered little encouragement saying that his office staff had failed to get it working the entire time they had had it. Nonetheless, undaunted, Tharchin began tinkering with the duplicator in an attempt to get it working. After two months of work in his spare time, Tharchin was finally greeted with success, and on October 10th, 1925, Tharchin produced the first issue of his very own Tibetan language newspaper, “The Mirror — News From Various Regions” (yul phyogs so so'i gsar 'gyur gyi me long). Following a brief hiatus, Tharchin commenced regular publication of his newspaper the following February with monthly issues to follow, and while receiving encouragement and advice from all around, his first real commendation came a year later, when he received a letter from His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama accompanied by a gift of twenty rupees stating that he was receiving Tharchin’s newspaper, “was very glad and added to continue it and send more news which would be very useful to him.”

Encouraged by this, Tharchin began to think of himself more and more as a newspaperman, expanding the scope of the newspaper beyond the simple relaying of news from other sources to the production of news content himself. With these goals in mind, Tharchin petitioned the Tibetan Government for permission to visit Lhasa as a reporter. With permission received, on August 20th, 1927, Tharchin headed for Gyantse, and from there left for Lhasa to conduct the first important interview of his career — an interview with His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. Arriving in Lhasa a month later, Tharchin remained self-conscious about his broken Tibetan -- the result of having grown-up in borderlands of Tibet -- and spent the better part of the next three months attempting to improve his speaking abilities before finally applying for an audience with His Holiness in mid-December. Success achieved, Tharchin returned to India the following February, receiving 100 rupees along the way from the British Political Officer at Gyantse, Arthur Hopkinson, to support him in the continued publication of the newspaper. By June, the Scottish Mission had received a new Litho Press, which Dr. Graham made available for Tharchin to use, and sending Tharchin to Calcutta to receive training in its use, Graham allowed him to use the press to produce his newspaper as part of his official duties at the Mission.

Although Tharchin had begun his newspaper with only fourteen subscriptions, by the third year his subscriptions were close to fifty, but Tharchin was still sending more than a hundred issues freely to officials in the Tibetan government although more than half of those were usually “lost” along the way by the Tibetan Post Office. These, however, were the least of Tharchin’s troubles and his greater opposition during these years came less from officials in Tibet, than from more hard-line missionaries who would soon appear in Kalimpong, in particular, Dr. Graham’s replacement at the Mission, the Australian missionary, Rev. Knox. Despite the often prominent and unsubtle “articles” on Christianity that appear in the pages of the Mirror with regularity, Knox was not favorably disposed to Tharchin’s activities as a newspaper editor, and shortly after arriving in Kalimpong brought an end to the subsidization of the Mirror — both in terms of material resources and Tharchin’s time. By the early-1930s, Tharchin had managed to stabilize the publication of his newspaper, although was constantly in search of new subscribers and advertising to underwrite his publication costs. It was thus with a certain degree of trepidation that Tharchin rejoined the Scottish Guild Mission in Kalimpong under Rev. Knox as “Tibetan Catechist,” agreeing to accept strict limits on his official activities in exchange for a salary. While there was little love lost between Tharchin and Knox, the position allowed Tharchin to continue his publication efforts, although eventually their differences would prove irreconcilable and they would part ways, with Tharchin pursuing his newspaper work on his own.

Over the next twenty-five years, Tharchin remained hard at work publishing his newspaper. What had begun as a personal vision and occasional medium for Christian propaganda going into Tibet, and which later morphed into a Tibetan language chronicle of world events (especially during World War II), by the 1950s became a vehicle for the fight for Tibetan freedom from the Chinese invasion and occupation. A major hub for information, Kalimpong and Tharchin’s newspaper offices in particular became a clearinghouse for news about the ongoing Chinese aggression in Tibet. In his offices, Tharchin received handwritten accounts of military occupations and aerial bombardments of monasteries and villages in eastern Tibet, which he published along with illustrations. Even in crude cartoon form, the picture Tharchin painted for his audience of events transpiring in Tibet was sobering and hard to believe, and the accounts would only get worse. Over the years that followed, the events unfolding in Tibet and in the rest of central Asia took their toll in very human terms, and even those who escaped Tibet were not immune from their effects. On more than one occasion, Tharchin would find himself writing the obituary for someone he had known, and as with many of the articles that Tharchin authored for his paper, these editorial reports would carry a deeply personal touch.

By the early 1960s, with financial troubles that never seemed to end, Tharchin ceased publication of his newspaper (1963) despite being offered a substantial sum of money and guaranteed subscriptions by the Chinese authorities in Tibet if he would publish pro-Chinese articles in his paper. With the Tibetan exile community growing and Tibetan language newspapers such as Freedom (rang dbang) and others beginning to be published, Tharchin decided that he had done his part on the world stage, and instead turned to put his energies into an orphanage that he and his wife had begun running years earlier. As the years passed and the Tibet Mirror Press became little more than a small historical artifact of the streets of Kalimpong, the Tibet Mirror newspaper would become Tharchin's greatest achievement, an invaluable legacy and testimony to the abilities of one man and to a once free and independent Tibet.