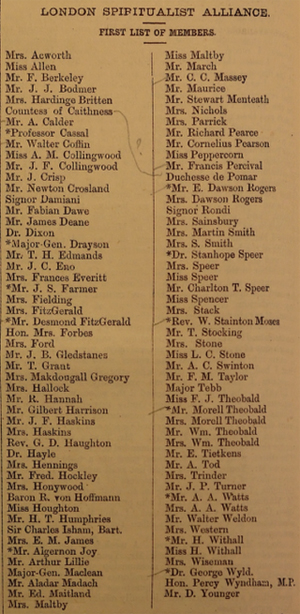

Part 1 of 2

Across Tibet from India to Chinaby Lieutenant-Colonel Count Ilia [Ilya Andreyevich] Tolstoy

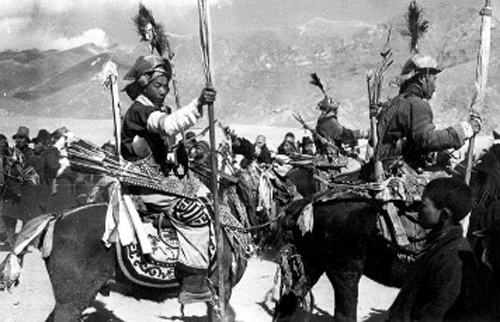

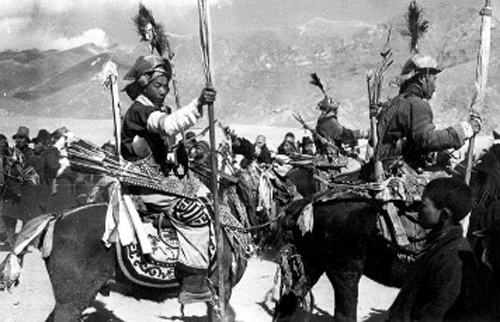

Tibetan Cavalry welcomed Count Tolstoy and Captain Dolan when they rode into Lhasa on their secret mission to "Shangri-La"

Tibetan Cavalry welcomed Count Tolstoy and Captain Dolan when they rode into Lhasa on their secret mission to "Shangri-La"In the Spring of 1942, when the war looked grimmer day by day to the Allies, and the Burma Road was lost, I was given the assignment of crossing Tibet from India to China. The venture, which was primarily to discover ways and routes of transporting supplies to China, was under the auspices of the Office of Strategic Services.

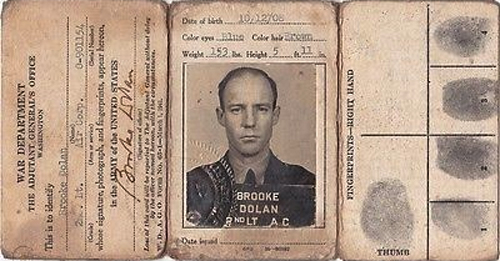

Given the choice of going alone or taking along a unit of personally picked men, I selected as my companion Capt. Brooke Dolan, who was then anchored to an Army Air Forces desk in Washington and was casting an eager eye around for overseas duty. The mission, I felt, would have a better chance of success if shared by two men. If one was lost, the other might get through.

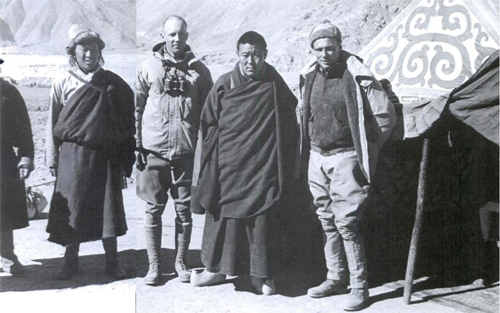

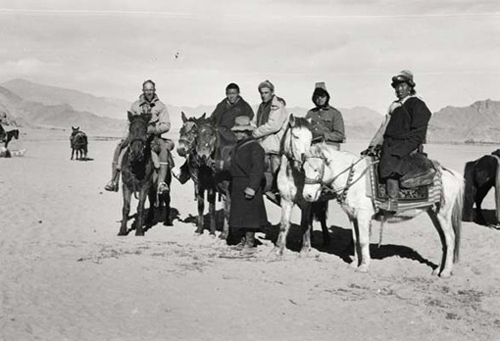

Colonel Count Ilia Tolstoy (left) and Captain Brooke Dolan (right) are greeted by a Tibetan official.President Roosevelt Greets the Dalai Lama

Colonel Count Ilia Tolstoy (left) and Captain Brooke Dolan (right) are greeted by a Tibetan official.President Roosevelt Greets the Dalai LamaSince Tibet proper is closed to all visitors, no permits to enter could be obtained in the United States. The best passport available for the trip was a letter from President Roosevelt to the Dalai Lama of Tibet. This we were to carry, together with the customary gifts to His Holiness and other officials in Lhasa.

On our departure from Washington by air in July, Col. (later Major General) "Wild Bill" Donovan, Director of OSS, bade us "Keep in touch if you can"— a hard task since radio equipment compact enough to carry on such a trip was not procurable at the time.

We carried 290 pounds of equipment, including vital instruments, cameras, film, etc., and 27 pounds each of personal belongings. In those days before the Air Transport Command was fully developed, bucket seats on planes were luxuries, and we slept on some of our cargo.

Arriving in Delhi, we reported to Lt. Gen. (now General) Joseph W. Stilwell, who was then China-Burma-India Theater commander. His rear echelon headquarters occupied only one wing of the Imperial Hotel in New Delhi, though it was the nucleus of the CBI forces.

In our negotiations with the Tibetans through the British Government offices in India, we were aided by Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Russell A. Osmun, USA; Capt. (later Lt. Col.) Charles Suydam Cutting, AUS, an ardent student of Tibet who had been to Lhasa twice in previous years; and George R. Merrill, Secretary of the U. S. Mission at New Delhi.

The success of the negotiations was due in part also to the warm support and assistance of O. K. Caroe, Secretary of External Affairs of the Government of India; Sir Basil John Gould, Political Officer for Sikkim and British Representative for Bhutan and Tibet; and Frank Ludlow, Additional British Political Officer for the same region, who at the time was already in Lhasa.

While arrangements with Lhasa were under way by British wireless, Brooke and I prepared for the trip.

India was in turmoil. There was rioting in the streets of Delhi, and the city was declared out of bounds. Finally, however, we were given a jeep with permission to go wherever we wished, and we darted around old and New Delhi, obtaining all needed supplies and equipment with the exception of a compact radio receiving set.

At the end of September, 1942, we were granted permission to proceed as far as Lhasa. Our prospects of going on from Lhasa to China looked exceedingly doubtful.

"Vinegar Joe" Stilwell's Best WishesBefore our departure General Stilwell found time to call us in and bid us Godspeed in his perfect Chinese. Late at night we struggled into our compartment on a train swarming with Hindus and troops. Our quarters were so jammed with thirty-odd pieces of equipment, all packed in containers for pack animal transport, that we had to sit on some of the cases. Luckily our train got through safely to Calcutta; the one behind us was derailed by rebels.

An overnight train took us on to SiIiguri. There we were met by Sandup, a 29-year-old Tibetan who had studied in English schools in India and was one of the post managers of the Tibetan telephone and telegraph line between Lhasa and India. He was to be our Number 1 man and interpreter on the journey to Lhasa and during our stay there.

With our gear piled into some aging touring Fords, we started a 70-mile climb through the lush vegetation of the Himalayan foothills into the State of Sikkim. The road, though narrow, was fair, damage from washouts and slides being repaired constantly by gangs of Gurkha and Lepcha laborers, mostly women.

We wound precariously along steep hillsides where the slightest swerve would have dropped us hundreds of feet into canyon streams. Once we came to a bridge so tottering that Sandup suggested our walking across and letting the cars go over one at a time.

We were soon in the toylike city of Gangtok, capital of Sikkim, whose Maharaja is much interested in promoting the welfare of his people. Here we were guests in the charming English country house of Sir Basil John Gould. B. J., as we called him, had represented the British Government at the inauguration of the present Dalai Lama. Though now more than 60 years of age, he thinks nothing of making the 300-mile journey to Lhasa.

We found him deeply engaged in the preparation of a new type of English-Tibetan dictionary and working out new methods for learning the Tibetan language. He speaks Tibetan, Hindustani, and Lepcha dialects and can write in those languages. Brooke and I absorbed from this remarkable man all we could about the customs and people of the country into which we were going.

While we were staying with B. J., the Prime Minister of Bhutan, Rani Dorji, with his charming Tibetan wife, was also visiting him. Madam Dorji was translating some Tibetan poetry and old ballads into English.

While we were preparing for the trip to Lhasa, Rai Sahib Sonnam, British trade agent from Yatung, the first Tibetan town of any importance on our route, came to Gangtok and gave us valuable assistance. He helped us organize our outfit and advised us on customs, procedures, protocol, and the presentation of gifts to officials along the way and in Lhasa.

Ready for the Trip to Forbidden LhasaWe were fortunate in finding a cook who later on became our Number 1 man, and an almost indispensable member of the party. Son of a Chinese father and Tibetan mother, he spoke enough English to act as our interpreter after Sandup left us. His name was Thami, which we changed immediately to Tommy. Our other newly engaged boy was Lakhpa, a quiet, hardworking Lepcha about 26 years old.

With our party thus augmented to five, plus whatever transport men were driving the animals, we struck out in clear October weather. The first pack train we hired from the Maharaja of Sikkim, and Rani Dorji lent us two of his fine riding mules as our mounts for the first part of the journey.

For three days, while we were winding up the side of a valley toward the top of a Himalayan pass, we could look back and see the little town of Gangtok with its palace on a knoll. Our overnight stops were at dak bungalows (Government rest-houses).

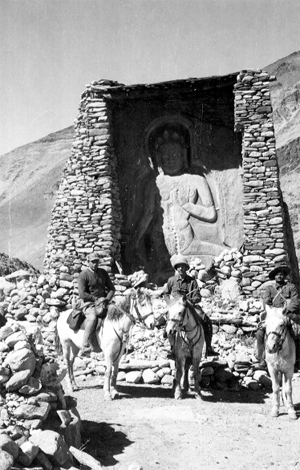

Tolstoy's caravan climbed dangerous Himalayan mountain paths such as this one on their way to the Forbidden City of Lhasa.

Tolstoy's caravan climbed dangerous Himalayan mountain paths such as this one on their way to the Forbidden City of Lhasa.Usually a day apart, these stretched on for 13 stages up to the city of Gyangtse. There was a keeper at each place, and although modern conveniences did not exist, the quarters were adequate and comfortable.

Nearing the summits, the road sometimes was only a trail so narrow that it was difficult to pass oncoming caravans burdened with bulging loads. Here and there slides made the trail almost impassable.

At 14,000 feet we sometimes felt the effect of the altitude and thin air and would wake up in the night gasping for breath. We found that propping ourselves in a semi sitting position was best for sleeping. In the daytime it was difficult to walk any distance uphill without frequent stops and rests, and we soon got used to doing everything as if in slow motion.

The Natu La (13,500 feet), first pass over the Himalayas, was surprisingly easy and level, with a good wide stretch of road approaching it. It is rocky, bare of vegetation, and in October free of snow. There was a little snow on slopes near by.

First Glimpse of Mysterious TibetFor a while we were in the clouds and could see neither behind nor ahead of us. Then the mists parted for a moment, allowing us to take our last look back at India and our first ahead into the thick, evergreen forests below us and the sea of ranges in the distance. We were looking down into mysterious Tibet.

A Tibetan outrider leads Tolstoy and his men into Tibet.

A Tibetan outrider leads Tolstoy and his men into Tibet.Leaving Natu La, we dismounted to spare our horses and walked down into Tibet over old washed-out trails. Our path in the valley of the Amo led often along dry freshet courses. On the way we paused to have a cup of buttered tea with the abbot of Kargyu Gompa (gompa, in Tibet, or gomba, in China, means "monastery"), the first small Tibetan monastery we encountered.

The headman of Yatung, on the Amo, met us with an escort about five miles from the city limits. Both our parties dismounted, and we performed the ceremony of exchanging scarfs, known as kattaks.

Rai Sahib Sonnam and several other acquaintances of the city greeted us just outside the town with military honors presented by a detachment of Indian Sepoy infantry in the employ of the Indian Army. We were then escorted to our quarters in a bungalow truly palatial for that territory.

Yatung is one of the larger Tibetan cities, though it numbers probably not more than 1,500 to 2,000 people. For livelihood the people depend upon agriculture and trade with passing caravans.

Tibetan Etiquette ComplicatedAs soon as we were settled, we were called upon by all the dignitaries of the city. They came with their servants, bringing gifts ranging from Tibetan carpets to yak butter and hen eggs. Our Number 1 man always knew when a caller was to arrive, and consequently we were prepared with the indispensable tea, and candies, cookies, and dried fruit.

The ceremonies of greeting varied with the importance of a caller. The more important he was, the farther away from the room we met him. We had to acquaint ourselves with the rules so as to know whether to greet a caller at the end of a room, at the door, in the yard, or at the front gate!

The day after our arrival in Yatung we had an early lunch with Rai Sahib Sonnam in his modern little home. Lunch was served in the Western style. We met here the first Tibetan of high social standing, Mary Taring, wife of a prominent young Tibetan official from Lhasa, and her two daughters. The younger girl was going to school in India, and the older was about to marry the son of Rani Dorji, Prime Minister of Bhutan. The Tarings later on became our great friends.

At that luncheon we also met Pangda Tsang, one of the two strong men in the Tibetan world of finance. He is a Yatung merchant, whose agency is scattered far and wide.

The next day we were invited to the first really Tibetan luncheon in the Tsangs' typical well-to-do Tibetan home. We rode out to the house with all our group, a thing that is always done, custom demanding that the host provide a good meal for the guest's retinue. Since we were considered high officials, we were expected to uphold the prestige of the United States.

Our three assistants and few pack animals made a show so unimpressive that we had to resort to the excuse that in wartime everything must be done simply and economically.

A Tibetan Luncheon PartyWith a throng of Tibetan guests Pangda Tsang's luncheon party was a gay affair. The food, more than abundant, consisted of Tibetan and Chinese delicacies, some of which had come from the coast of China before the war. We ate our meal with chopsticks, washing it down with many cups of tea and also with chang, the Tibetan national drink, made of lightly fermented barley.

We had regular Chinese shark-fin soup, some small ocean shrimp originally dried, transparent noodles made from pea flour, pickled vegetables (cabbage, cucumber, and a sort of cross between a chutney and a pickle), boiled rice, several dishes of cold and hot meat prepared in different ways, and round balls of dough stuffed with meat, fruit, or brown sugar and then boiled or steamed. These last had been pinched all around before steaming and stained with a red dye. The final course was a succulent noodle dish.

The soup dish and dessert were eaten in the middle of the meal. Dessert, served hot, was a syruplike jelly containing raisins and apricots.

Pangda Tsang asked us when the United States would again buy Tibetan wool. Before the war the bulk of Tibetan wool had been sold to the United States for manufacture of auto rugs, but the war had cut off the export and the Tibetans were temporarily without this important source of revenue. I referred the inquiry to Washington.

We soon realized that Tibetans who knew of the United States were interested in the outcome of the war and had a sympathetic feeling toward us. They had, however, great doubt as to our ability to defeat Japan, since at the time Japan was almost at their border.

A Letter from the Dalai Lama's CourtIn taking our leave from the party, we left, through our Number 1 man, the customary adequate tip for our host's chief servant. Several of Pangda Tsang's riders escorted us to our home. This was good etiquette on such occasions, for the more gaily a guest departs, the better proof to all the neighborhood that the entertainment was lavish.

While we were at Yatung, we received from Lhasa the Red Arrow Letter, a courtesy gesture from the Dalai Lama's court for traveling through the country.

This letter was a piece of red cotton cloth, about 16 inches wide and 2 feet long, to be carried in the bosom or on a staff by an outrider who would precede the party by one or two days. It stated that two American officers were en route to visit the Dalai Lama and requested the headmen of all the villages to supply them with accommodations and transport at a certain rate.

Given a military send-off with honors when we left Yatung, we proceeded up the valley toward the next town of Phari Dzong, several days' journey away.

We passed some scattered villages, their houses built of stone with shingled roofs, and went through little meadows of Li Ma Tang, the only flat grassland we had seen on the bottom of the valley. It was haying time. The villagers had their tents pitched in the meadows and were cutting the grass with scythes, then raking it to dry.

The trail was crowded with little donkeys and mules almost completely hidden under their loads of hay. Even old men and women were carrying enormous backloads.

The Loftiest Post Office in the WorldOur first panoramic view of the typical Tibetan town of Phari Dzong and the country around it was truly magnificent. Here we were greeted by the distinguished old administrator, who is also the abbot of the local monastery of 400 monks. We stayed in the compound of a Tibetan house that also served as the post office for the Tibetans, supposedly the highest-situated post office in the world.

Some crops are grown in the country around Phari Dzong, and barley can be planted above a 15,000-foot altitude. In the plains and foothills we saw some of the first black tents of the nomads and herders, with their winter corrals and homes made out of yak dung and sod.

The weather was freezing, high winds sweeping across the plain with great velocity. Because the Himalayas catch almost all the precipitation from the south, this territory is virtually arid.

Our road climbed so high that the passes were hardly noticeable. They were nothing but rolling, saddlelike open stretches, adorned with the customary sacred mani stone piles and prayer flags and stone pillars.

On October 22 we crossed a pass of this type called Tang La, 15,200 feet, which is part of the great Himalayas, and entered into the approaches of the vast Tuna plain.

Along the road we kept meeting caravans, mostly mules, donkeys, and bullocks, loaded down with wool, marmot hides, and grain. Occasionally we ran into a party of armed merchants from some of the outlying districts of Tibet, all well clothed and mounted, some of them wearing gaily painted masks and goggles as a protection from dry wind, sand, and sun.

At a little place called Dochen we came upon one of the most beautiful panoramas we saw in Tibet, where the deep-blue waters of Ram Tso reflect for miles the Himalayan range beyond, with the vast mountain Chomo Lhari towering over it. There was a little ice along the shores of the mirror-calm lake. Thousands of bar-headed geese lined the shore, and flocks of ruddy sheldrakes, or Brahmany ducks, were filling the air with a moaning cry.

In that region the natives had few horses, and our transport consisted entirely of bullocks, often tended by women or young boys.

A Sportsman's Paradise, but ClosedWhere the salty Kala Tso without outlet is slowly receding, there is considerable crop raising, and we watched the native farmers at work in their fields. Taking Sandup and a native with me, I climbed a 2,000-foot promontory in search of Tibetan bighorns (Ovis ammon hodgsoni). Five rams, one with a magnificent head, paused less than 100 yards from our place of vantage!

Unfortunately for my huntsman's desires, it is against the Tibetan religion and the wish of the Dalai Lama to kill wild game. I had to be satisfied with a rather long-view photograph of the animals.

The next day we crossed the Kala plain, its little tufts of grass reminiscent of some parts of our West. Brooke and I were tempted again when we began running into kiang, the wild ass of Asia, and gazelles.

In the little village of Samada great fall activities were in progress. Manure was carried to the fields in baskets on pack animals, neatly deposited on the soil, and covered up with dirt to prevent it from being blown away.

Knee-deep in barley and peas, domestic animals were being driven round and round threshing floors. Here and there the grain was being hand-winnowed, and along a stream women and children were washing peas in brass cauldrons and woven baskets.

In the afternoon we visited the village of the Porus people, nearest caste counterpart in Tibet to the Untouchables of India, though without doubt much happier than the lowest-caste Hindus. Several families of them lived in semi-cave houses on a hillside a mile or so from the main village. These people, though

they till the soil, gain their primary livelihood by disposing of the dead and butchering cattle for the other villagers.

In Tibet people are not usually buried. The Porus carry bodies to a hilltop where, with the skill of a surgeon, they cut them into portions small enough to be devoured by vultures. The Porus are paid for this task and also inherit certain silver decorations from the dead. Those we saw were well bedecked in silver.

Some cattle herders or nomads came down into the village to trade. Magnificent specimens of manhood, they were clothed only in sheepskin chupas (capelike coats) and trousers. They wore no hats, but had long braids wound about their heads. Apparently the weather in the 12,000-foot valley was too hot for them! They wore their chupas with one arm slipped out, exposing half their bodies above the waist.

A Telephone in the CloudlandsWe stopped overnight at the Kangmar dak bungalow where there is a telephone station. Occasionally one can communicate with either Gangtok or Gyangtse from there, and rarely with Lhasa. This telephone operates spasmodically. Sometimes it is silent for two or three weeks at a stretch when some brigand gets away with a span or two of the wire. If an offender is caught, the punishment is severe, usually the chopping off of one hand.

Our Number 1 man, Sandup, had his home station here, and we met his young wife and two-year-old baby daughter. In the yard of the bungalow a few potted plants added a touch of charm.

That night while we were finishing supper, Sandup approached us with troubled countenance. He was anxious to take his wife and baby along with us to Lhasa. As a rule, women of Asia are good travelers, and nomad women follow their men, doing work under all conditions. We did not hesitate to grant the requested permission. Sandup's wife was a great help to us all on the trip to Lhasa, and the baby girl became our mascot.

A few miles farther on, an ancient monastery perches above the 16,000-foot elevation. I gave our pack animals a day of rest and, taking Sandup with me as interpreter, went on ponyback to the place. The abbot, a stalwart man under middle age, told me I was the first white man to visit the monastery.

Captain Dolan Falls IllAt Gyangtse, an important town and the last British trade and mail post, we were met by Maj. R. Gloyne, acting British trade agent, Lt. C. Finch, and Dr. G. H. F. Humphries, with a colorful honor guard. The guardsmen were of a Sepoy infantry detachment mounted on fine matched white Mongolian ponies. They carried British colors. With the British officials were Rai Sahib Wangdi, a Tibetan kingpin in the trade agency, and many other Tibetan city officials.

Very unfortunately, on the second day in Gyangtse, Captain Dolan was stricken with pneumonia. We gave him sulfa treatment, which arrested the progress of the illness immediately, but because of the high altitude and extremely cold weather his recovery was not so rapid as we hoped. For that reason, we were glad that Dr. Humphries was allowed to travel with us to Lhasa.

We stayed in Gyangtse for a month. Two or three times we were fortunate enough to make telephone connections with Mr. Ludlow in Lhasa and discuss with him certain phases of the journey from Gyangtse and the arrival in the Sacred City.

Some of our mail caught up with us there, and the radio of the Agency gave us daily the rather grim news of the outside world.

The British, with their love of sports, had carried that phase of their life into this part of Tibet. The Agency's Tibetan employees had a good soccer team, playing against the men of the Sepoy detachment and the British commanding personnel.

Played at an altitude of 13,000 feet, the games were amazingly fast. Almost without exception they were won by the Tibetans, who not only were fine physical specimens but were accustomed from childhood to rarefied air. Major Gloyne and I made an attempt to play, but soon found that the only positions we could handle were those of goalkeepers.

I undertook the job of giving cavalry drills and training to the newly arrived Sepoys. Every morning we went through a couple of hours in the saddle, sometimes even knocking a polo ball around. To my long experience as a horseman and my skill in caring for saddle animals I attribute the ease with which I made friends with the horse-loving Tibetans.

In the heart of the city is located one of the large and important monasteries of Tibet, Nenning Gompa, in front of which is a gigantic chorten, or shrine, of unique design and beauty, famous all over Tibet. Inside, it contains 80 chambers filled with Buddhist idols and paintings of many types and sizes. It is adorned with gilded religious figures and ornaments.

Gyangtse is situated in a fertile valley criss-crossed with irrigation ditches which our Mongolian ponies took in their stride during our cross-country rides. It is one of the key cities of Tibet, and through it passes all the trade from the east to India and northwest Tibet.

The Agency compound had electric power, generated by a windmill. A few electric-light bulbs made it quite modern, enticing us to later evenings and long conversations with our Tibetan and British friends.

On the Last Lap to LhasaThe month passed quickly, and on December 4, after a military review of the detachment and numerous calls from high Tibetan officials, we rode out with Major Gloyne and his honor guard toward Lhasa. They escorted us a short distance before turning back; but Dr. Humphries stayed with us. Due for return to India after long service in Gyangtse, he readily obtained permission to visit the Forbidden City. The Anglo-Indian doctor amused us and all the Tibetans by riding, instead of a horse, the smallest mule he could find.

The court of the Dalai Lama had sent two soldiers, a sergeant and a private, to escort us to Lhasa. With pronged rifle across his back and a large silver prayer box slung from one shoulder, the sergeant rode ahead, usually on the best pony he could requisition from the village. His mount was bedecked with ornaments and bells. Had there been any bandits, they would certainly have heard our approach well ahead of time.

When Caravans MeetBy always preceding us, the sergeant added a great air of dignity to our procession, sometimes roughly making approaching caravans get off the road to allow us more room to pass.

Tibetan custom rules that if a traveler sees what might be a more important caravan approaching, he stops within a few hundred yards, gets off the road, dismounts, takes off his hat, and stands while the party passes by. The party, in turn, must greet the dismounted travelers most politely.

Somehow, after leaving Gyangtse, we had the feeling of getting deeper into the real Tibet where the influence of the outside world is negligible. The trails had been worn through the centuries by caravans carrying merchandise from northeast China and India. Although we had to cross several more passes on our way, the terrain was not difficult.

We were meeting more caravans, now mostly of yaks, carrying barley, salt, and wool. It was easy to see that they had been on the trail for months. From this point on we stayed in Tibetan houses, which often were vacated by their occupants for our overnight use.

The headman and owner of the house usually would bustle about and try to make us comfortable, constantly bowing, bringing up the thumbs, sticking out the tongue and hissing—Tibetan ways of showing respect.

The higher the station of the person addressed, and the lower the station of the one who addresses, the lower the latter must bow, the more he is to stick out his tongue, and the more constant must become the hissing, done with quick little intakes of breath. After a while we got used to this and almost did it ourselves. Although we resorted to saluting as an official or any other form of greeting, we often found ourselves bowing while saluting.

In the little village of Ralung at the base of the Ningohi Kangshar mountain, we stayed in the large house of a Tibetan nobleman.

Curtain-like pieces of cloth with little cutouts to admit light were the typical Tibetan substitutes for window glass. The only heat came from charcoal burners, which used yak chips for fuel instead of charcoal. These burners were lighted outside and brought in glowing hot. We got the sensation of heat by sitting almost on top of the burner.

By keeping all our clothes on indoors, we managed to make the entries in our log; then, undressing as quickly as possible, we got into our sleeping bags for the night. The yak chips used in the poorer houses are burned right in the room, which consequently is filled with an almost suffocating smoke.

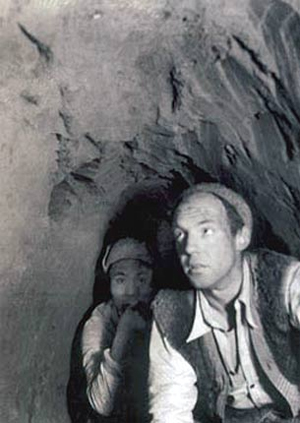

From Ralung we toiled up to Karo La, altitude 16,000 feet, one of the most dangerous passes because of frequent snowfalls.

The animals were tired from the long, tedious climb, and we paused overnight beyond the pass in a Tibetan mail stage shack. It was a windy and bitterly cold night. All of us huddled into a tiny windowless room, filled with the smoke of burning yak chips, while the animals were huddled together outside in a small yard.

Sandup's wife and baby daughter amazed me by their indifference to the discomfort of the trail. I never heard the baby cry, and she was sick only once—then, I think, from some of our candies. She would ride usually either in the arms of her mother or in the saddle in front of another rider.

From Karo La we descended to Yamdrok Tso, near which is situated the small but important town of Nagartse Dzong, with its striking hillside fort guarding the narrows of the valley.

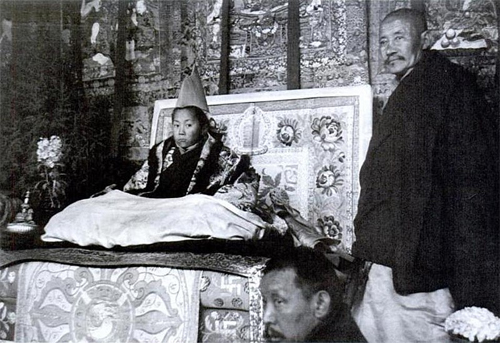

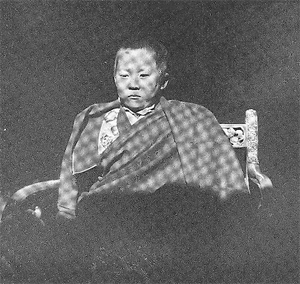

The "Diamond Sow," a 5-year-old AbbessWe remained in Nagartse Dzong an extra day to visit the famous Samden Gompa, which is headed by an abbess known as the "Diamond Sow." She is abbess over male monks.

The first Diamond Sow abbess dates from 1717, when the monastery was besieged by a band of Mongols. It was a nunnery then. After a long siege the abbess is said to have opened the gates at the monastery yard, turning all her nuns into sows at the same time. The Mongols were so impressed with the miracle that they laid down their arms and retreated. The museum room of the monastery contains large quantities of those weapons.

The abbess at the time of our visit was five years old. She received us sitting cross-legged on her throne with her lay female attendant and her ecclesiastical court monks. Her well-proportioned and chiseled face was stern with a grown-up expression. At no time could I notice any mannerisms of a child.

We presented scarfs directly to her, and the gifts and money donations for the monastery were brought in as usual. We in turn were presented with two fragments of a sacred kattak and some magic seeds wrapped up in Tibetan paper with prayers.

A good Tibetan places these objects in his prayer box, which at home is kept in the religious corner found in every Tibetan house, no matter how poor, and on a journey is carried slung across the shoulder. The Tibetans believe that some strong medicine contained in these prayer boxes will divert a bullet.

Brooke impressed even the monks with his knowledge of the images, which he recognized at a glance. I explained that he was a student of the Buddhist religion. Thereafter, this fact became known wherever he went and gained for our party a scholastic and religious respect.

Well-to-do Tibetans Wear Fine RaimentAt Japsan Ferry, by which we crossed the Brahmaputra, we met the first well-to-do Tibetan family on the march. They were mounted on fine mules bedecked with rug blankets and ornamented tack, with large red woolen tassels hanging from their breastplates. A child was held in the saddle by an arrangement of high wooden crosstrees on pommel and cantle.

Loading the Riding Horses and Pack Mules on the river barge.

Loading the Riding Horses and Pack Mules on the river barge.The family was dressed in fine silk robes adorned with furs, and wore fur hats in a cutoff conical shape embroidered with gold thread. All the servants wore the same type of colored robes and were well armed with rifles and Mauser pistols.

I was often asked if we were traveling in uniform. Most of our clothing which we wore every day was of the combat type, but we carried with us blouses, riding breeches, and boots, which we made a point to wear for official calls and for certain arrivals and departures at the more important points. Several times we had to fight high winds behind some hill a few miles outside a village while we changed into our best.

At a small village called Chushul Dzong the headman informed us that the famous Tsarong Shape, a Cabinet Minister, had offered us the use of his small overnight cottage. It was a gracious Tibetan building, with several modern conveniences.

In the big reception room we were astonished to find the walls covered with National Geographic Society maps of the world. Later we learned that Tsarong Shape, whose full name is Namgang Dasan Damdu, is the only Tibetan member of The Society. We saw much of him in Lhasa.

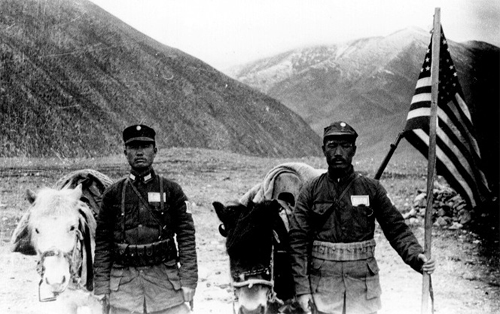

Dalai Lama's Escort Meets the PartyTwenty-five miles out of Lhasa we were met by an escort sent out from the court of the Dalai Lama to greet us. It was headed by a powerfully built, fine-looking young monk, Kusho Yonton Singhi, who was to become our guide and inseparable adviser during our stay in the city of mystery.

Tibetan officials such as these negotiated the possibility of allowing Roosevelt and Churchill to create a road from India to China via their mountainous kingdom.

Tibetan officials such as these negotiated the possibility of allowing Roosevelt and Churchill to create a road from India to China via their mountainous kingdom.He presented us with a warm letter of welcome and greetings from the joint Foreign Ministers of Tibet, and with the usual scarfs. Knowing our animals were tired, the Ministers had sent two fresh ponies for Brooke and me. It was a pleasure to ride the excellent Mongolian pacer, the kind that in Tibet only wealthy men can afford.

By Tibetan custom horsemen walk down steep hills, but from the moment Kusho joined us, we were not obliged to dismount. One of Kusho's outriders would halt at the top of each steep place, give his horse into charge of someone else, and lead our mounts carefully down the trail. We began to feel as if we were precious china dolls.

At noon we rode up to several gaily decorated Tibetan tents, where we had tea with our guide. The next day we woke up early and rode off briskly with an unmistakable feeling of excitement. Our first goal was near.

Entering the valley of Lhasa, we rode along the Kyi, which flows through the city. We crossed its tributary on Tibet's only modern steel bridge. On a concrete foundation, the bridge was built several years ago by Tsarong without the help of foreign engineers. The feat was remarkable in that all the pieces of steel had to be brought from India over the Himalayas by coolies, as the girders were too heavy for pack animals to carry.

Somewhere within the last four miles of Lhasa we knew a delegation waited to receive us, and one of our men rode ahead to herald our approach. The greeters, thus notified, rode out to meet us a couple of hundred yards from the place where they had been stationed. When about 100 feet apart, our parties dismounted and greeted each other.

The welcoming delegation was composed of the city magistrate of Lhasa, representing the city; Frank Ludlow, Additional British Political Officer for Sikkim, Bhutan, and Tibet, with H. Fox, Esquire, his assistant and wireless operator; the British Mission doctor, Rai Sahib Bo, who was a Bhutanese by birth; chief British Mission clerk, Minghyu; Dr. Kung Ching-tsung, chief of the Chinese Mission, with several members of his staff; the Bhutanese representatives; the Nepalese representatives, whose honor guard of soldiers was lined up a few miles away; and the Ladakhi representatives.