by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/17/20

Meanwhile, even as Mao spoke in December 1947 a shift was occurring within the Indian Communist party which was bringing into control a faction which interpreted Zhdanov's September directive simplistically, not only assuming it to be a call for armed struggle against the Nehru government but also seeing it as a demand for a limited worker-peasant alliance against all sections of the Indian bourgeoisie to bring about a one-stage revolution overthrowing capitalism and ushering in socialism. This shift took place at a December 1947 CPI central committee meeting in which the balance of power within the party swung away from P. C. Joshi — the old CPI general secretary who had led the party since the middle thirties, and who had advocated support for the new Nehru government — toward B.T. Ranadive, who has since to this day remained at least the titular leader of the CPI leftist faction. The central committee adopted a resolution making no distinction between sections of the Indian bourgeoisie, and lumping all of the bourgeoisie with imperialism and feudalism as the enemy to be fought now.

This line was confirmed and developed three months later at the Second Congress of the CPI in February 1948, when Ranadive formally replaced Joshi as general secretary. The Political Thesis adopted by this congress identified the entire world bourgeoisie with the imperialist camp as the common enemy in every country; explicitly rejected the notion of significant differences among the bourgeoisie; called for a united front from below (to entice away the proletarian following of the Congress party) rather than a united front from above (which would have meant the Joshi line of alliances with and support for Congress party leaders); held that "a revolutionary situation now existed in India, and called for a violent effort to bring about a one-stage revolution. This party congress was held in Calcutta immediately upon the conclusion of an international youth congress there sponsored jointly by the World Federation of Democratic Youth and the International Union of Students which is believed to have given the signal for the armed Communist uprisings which soon afterward began in a number of other Asian countries.

-- The Indian Communist Party and the Sino-Soviet Dispute, by Office of Current Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency

World Federation of Democratic Youth

Formation: 10 November 1945; 74 years ago

Founded at: London

Headquarters: Budapest, Hungary

President: UJCE - Aritz Rodríguez

Secretary General: UJC - Yusdaquy Larduet

Vice President: ULDY - Adnan Al Mokdad

Vice President: Lasantha Abeywarna

Affiliations: ECOSOC (general consultative status); UNESCO

Website http://www.wfdy.org

The World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY) is an international youth organization, recognized by the United Nations as an international youth non-governmental organization, and has historically characterized itself as anti-imperialist and left-wing. WFDY was founded in London in 1945 as a broad international youth movement, organized in the context of the end of World War II with the aim of uniting youth from the Allies behind an anti-fascist platform that was broadly pro-peace, anti-nuclear war, expressing friendship between youth of the capitalist and socialist nations. The WFDY Headquarters are in Budapest, Hungary. The main event of WFDY is the World Festival of Youth and Students. The last festival was held in Sochi, Russia, in October 2017. It was one of the first organizations granted general consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council.

History

On 10 November 1945, the World Youth Conference, organized in London, founded the World Federation of Democratic Youth. This historic conference was convened at the initiative of the World Youth Council which was formed during World War II to encourage the fight against fascism by the youth of the allied nations. The conference brought together, for the first time in the history of the international youth movement, representatives of more than 30,000,000 young people of diverse different political ideologies and religious beliefs from 63 nations. It adopted a pledge for peace.

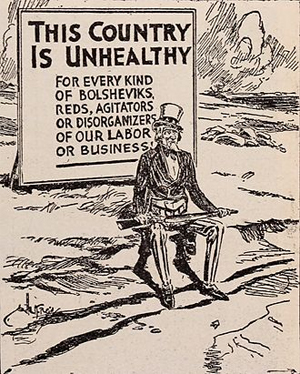

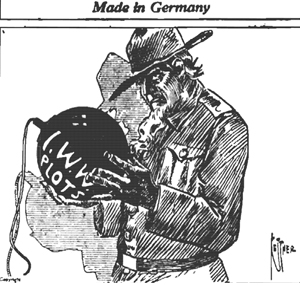

Shortly after, with the onset of the Cold War and Winston Churchill's Iron Curtain speech, the organization was accused by the US State Department of being a "Moscow front". Many of the founding organizations quit, leaving mostly youth from socialist nations, national liberation movements, and communist youth.[1] Like the International Union of Students (IUS) and other pro-Soviet organizations, the WFDY became a target and victim of CIA espionage as well as part of active measures conducted by the Soviet state security.[2][3][4][5]

The WFYD's first General Secretary, Alexander Shelepin, was a former leader of the Young Communist International which had been dissolved in 1943. Shelepin had been a guerilla fighter during World War II (after his work with the WFDY, he was appointed head of Soviet State Security).[2] Both the WFDY and IUS vocally criticized the Marshall Plan, supported the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 and the new People's Democracies in Europe. They opposed the Korean War.[2]

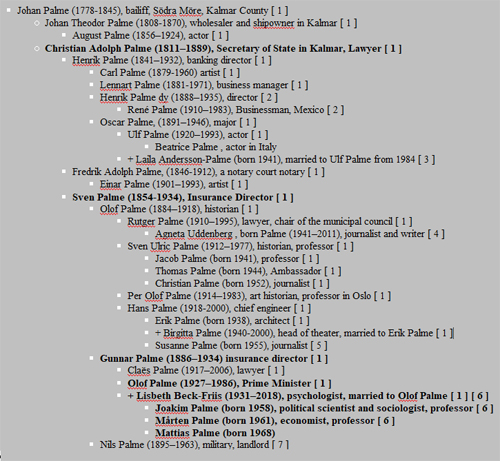

The main event of the WFDY became the World Festival of Youth and Students, a massive political and cultural celebration for peace and friendship between the youth of the world. Most, but not all, of the early festivals were held in socialist nations in Europe. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s the WFDY's festivals were one of the few places where young people from the so-called "Free World" could meet youth struggling against apartheid from South Africa, or militant youth from Vietnam, Palestine, Cuba and other nations. Famous people who participated in festivals included Angela Davis, Yuri Gagarin, Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro, Ruth First, Jan Myrdal and Nelson Mandela.

When the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc collapsed, the WFDY entered a crisis. With the power vacuum left by the collapse of the most important member organization, the Soviet Komsomol, there were conflicting views of the future character of the organization. Some wanted a more apolitical structure, whereas others were more inclined to an openly leftist federation. The WFDY, however, survived this crisis, and is today an active international youth organization that holds regular activities.

Pledge

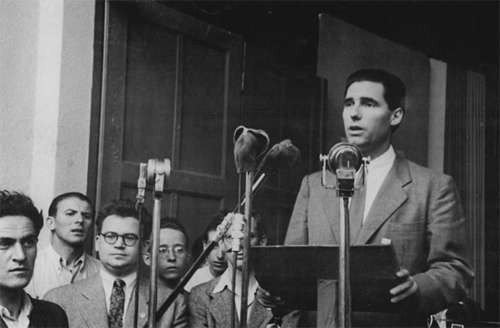

Guy de Boisson, President of the World Federation of Democratic Youth, speaks at the opening of the 2nd World Festival of Youth and Students (Budapest, 1949).

We pledge that we shall remember this unity, forged in this month, November 1945

Not only today, not only this week, this year, but always Until we have built the world we have dreamed of and fought for We pledge ourselves to build the unity of youth of the world All races, all colors, all nationalities, all beliefs To eliminate all traces of fascism from the earth To build a deep and sincere international friendship among the peoples of the world To keep a just lasting peace To eliminate want, frustration and enforced idleness

We have come to confirm the unity of all youth salute our comrades who have died-and pledge our word that skilful hands, keen brains and young enthusiasm shall never more be wasted in war

— Pledge of the World Federation of Democratic Youth

General Assembly

The WFDY conducts a General Assembly every four years, the last taking place in Nikosia in 2019.[6] During the Assembly, leadership and a General Council are elected and an organisational declaration is approved.[7]

Member organizations

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

Africa

Country / Name / Notes / Ref

Angola Juventude do Movimento Popular da Libertação de Angola Youth wing of MPLA [8]

Congo, Dem. Rep. PPRD Youth League Youth wing of the People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy

Eritrea National Union of Eritrean Youth and Students [8]

Ethiopia Ethiopian Youth League [8]

Ghana Democratic Youth League of Ghana

African Youth Command

Mozambique Mozambican Youth Organisation Youth wing of FRELIMO [8]

Namibia SWAPO Party Youth League Youth wing of SWAPO

Senegal Mouvement de la Jeunesse Démocratique Youth wing of the Democratic League/Movement for the Labour Party

UJDAN Youth wing of the Party of Independence and Labour

South Africa African National Congress Youth League Youth wing of the African National Congress [8]

South African Students Congress

Young Communist League of South Africa Youth wing of the South African Communist Party

Sudan Sudanese Youth Union Youth wing of the Sudanese Communist Party

Tanzania Umoja Wa Vijana Youth wing of Chama Cha Mapinduzi [8]

Senegal Democratic Youth Union Alboury Ndiaye Youth wing of the Party of Independence and Work

Western Sahara Saharawi Youth Union Youth wing of the Polisario Front [8]

Zambia United National Independence Party Youth League Youth wing of the United National Independence Party

Zimbabwe ZANU-PF Youth League Youth wing of ZANU-PF [8]

Asia and the Pacific

Country / Name / Notes / Ref

Australia Resistance: Young Socialist Alliance Youth wing of the Socialist Alliance

Bangladesh Socialist Students' Front Student wing of the Socialist Party of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Students Union

Bangladesh Youth Union Youth wing of the Communist Party of Bangladesh [8]

Bhutan Democratic Youth of Bhutan Youth wing of the Bhutan National Democratic Party

Students Union of Bhutan

India All India Students Federation Student wing of the Communist Party of India

All India Youth Federation Youth wing of the Communist Party of India [8]

Students Federation of India Student wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

Democratic Youth Federation of India Youth Wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

All India Youth League Youth wing of the All India Forward Bloc

Iran Tudeh Youth Youth wing of the Tudeh Party of Iran [9]

Japan Japan League of Socialist Youth [8]

Korean Youth League in Japan Youth wing of Chongryon

Korea, DPR Kimilsungist-Kimjongilist Youth League Youth wing of the Workers' Party of Korea [8]

Korea, Rep. 7th-term Hanchongryun

Laos Lao People's Revolutionary Youth Union Youth wing of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party

Myanmar All Burma Students' Democratic Front

All Burma Students League

Nepal All Nepal National Free Students Union Student wing of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist)

Youth Federation Nepal Youth wing of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) [8]

Nepal National Federation of Students Student wing of the Nepal Communist Party (United)

Nepal National Youth Federation Youth wing of the Nepal Communist Party (United)

Pakistan Democratic Students Federation Student wing of the Communist Party of Pakistan

Pashtoonkhwa Students Organization

Philippines ANAKBAYAN

Sri Lanka Communist Youth Federation Youth wing of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka National Union Of Students Student wing of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka

Federation of All Lanka(Ceylon) Youth League Youth wing of Mahajana Eksath Peramuna

Socialist Students Union Student wing of Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna [8]

Socialist Youth Union Youth wing of Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna

Vietnam Ho Chi Minh Communist Youth Union Youth wing of the Communist Party of Vietnam [8]

Vietnam Youth Federation

Europe and North America

Country / Name / Notes / Ref

Armenia Young Communist League Armenia Youth wing of the Armenian Communist Party

Azerbaijan Young Communist League Azerbaijan Youth wing of the Azerbaijan Communist Party

Austria Communist Youth of Austria

Belgium COMAC Youth wing of the Workers' Party of Belgium

Bulgaria Bulgarian Socialist Youth Union

Canada Young Communist League of Canada Affiliated with the Communist Party of Canada

Catalonia Communist Youth of Catalonia Youth wing of the Communists of Catalonia

Czech Republic Communist Youth Union Youth wing of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia [8]

Cyprus United Democratic Youth Organisation Youth wing of the Progressive Party of Working People [8]

Denmark Ungkommunisterne Shared youth organization of the Communist Party in Denmark and the Communist Party of Denmark

Finland Communist Youth League

France Mouvement Jeunes Communistes de France

Georgia Young Communist League of Georgia

Germany Free German Youth

Socialist German Workers Youth Youth wing of the German Communist Party [8]

Greece Communist Youth of Greece Youth wing of the Communist Party of Greece [8]

Hungary Baloldali Front Youth wing of the Hungarian Workers' Party

Ireland Connolly Youth Movement Youth wing of the Communist Party of Ireland

Workers Party Youth Youth wing of the Workers' Party of Ireland

Italy Italian Young Communist Federation Youth wing of the Italian Communist Party; known as Youth Federation of Italian Communists until 2016

Front of the Communist Youth Youth wing of the Communist Party

Giovani Comuniste e Comunisti Youth wing of the Communist Refoundation Party

Republic of Moldova Young Communist League of the Republic of Moldova Youth wing of the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova

Norway Young Communists in Norway Youth wing of the Communist Party of Norway

Young Communist League of Norway

Portugal Portuguese Communist Youth Youth wing of the Portuguese Communist Party [8]

Russia Leninist Young Communist League of the Russian Federation Youth wing of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation

Revolutionary Communist Youth League (Bolshevik) Youth wing of the Russian Communist Workers' Party of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Serbia Young Communist League of Yugoslavia Youth wing of the New Communist Party of Yugoslavia

Slovakia Socialistický Zväz Mladých Youth wing of the Communist Party of Slovakia

Spain Collectives of Communist Youth Youth wing of the Communist Party of the Workers of Spain

Communist Youth Union of Spain Youth wing of the Communist Party of Spain [8]

Sweden Communist Youth of Sweden Youth wing of the Communist Party of Sweden

Switzerland Communist Youth of Switzerland Youth wing of the Swiss Party of Labour

Turkey Communist Youth of Turkey Youth wing of the Communist Party of Turkey [8]

Ukraine Komsomol of Ukraine Youth wing of the Communist Party of Ukraine

United Kingdom Young Communist League Youth wing of the Communist Party of Britain

Young Socialists Youth wing of the Communist League

United States Young Socialists Youth wing of the Socialist Workers Party

Latin America and Caribbean

Country / Name / Notes / Ref

Argentina Federación Juvenil Comunista Youth wing of the Communist Party of Argentina [8]

Barbados League of Progressive Youth

Bolivia Juventud Comunista de Bolivia Youth wing of the Communist Party of Bolivia

Brazil Juventude Revolucionaria 8 de Outubro Youth wing of the MR-8

Juventude do PDT Youth wing of the Democratic Labour Party

Juventude do PMDB Youth wing of the Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement

Juventude Comunista Avançando Youth wing of the Polo Comunista Luiz Carlos Prestes

União da Juventude Comunista Youth wing of the Brazilian Communist Party [8]

União da Juventude Socialista Youth wing of the Communist Party of Brazil [8]

Juventude Socialista Brasileira Youth wing of the Brazilian Socialist Party

Chile Juventudes Comunistas de Chile Youth wing of the Communist Party of Chile [8]

Colombia Juventud Comunista de Colombia Youth wing of the Colombian Communist Party [8]

Costa Rica Juventud Frente Amplio Youth wing of the Broad Front (Costa Rica) [8]

Cuba Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas Youth wing of the Communist Party of Cuba [8]

Ecuador Federación Estudiantes Universitarios

Juventud Socialista Ecuatoriana Youth wing of the Socialist Party of Ecuador

El Salvador Juventud del Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional Youth wing of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front

Grenada Maurice Bishop Youth Movement

Guatemala Juventud URNG Youth wing of the URNG

Guyana Guyana Youth and Students Movement

Walter Rodney Youth Movement

Mexico Federation of Young Communists Youth wing of the Communist Party of Mexico

Juventud Popular Socialista Youth wing of the Popular Socialist Party [8]

Nicaragua Juventud Sandinista 19 de Julio Youth wing of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional

Paraguay Casa de la Juventud del Paraguay

Peru Juventud Comunista Peruana Youth wing of the Peruvian Communist Party

Uruguay Juventud del Movimiento 26 de Marzo Youth wing of the 26 March Movement

Venezuela Juventud Comunista de Venezuela Youth wing of the Communist Party of Venezuela [8]

United Socialist Party of Venezuela Youth Youth wing of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela

Middle East

Country / Name / Notes / Ref

Algeria Union de la Jeunesse Algérienne Youth wing of the FLN

National Union of Algerian Students Students of the FLN

Egypt Union of Progressive Youth of Egypt Youth wing of the Progressive National Unionist Party [8]

Iraq Iraqi Democratic Youth Federation Youth wing of the Iraqi Communist Party [8]

General Union of Students in Iraqi Republic

Israel Young Communist League of Israel [he] Youth wing of the Communist Party of Israel [8]

Lebanon Union of Lebanese Democratic Youth Youth wing of the Lebanese Communist Party [8]

Libya National Youth Organization of Libya

Bahrain Shabeeba Society of Bahrain Youth wing of the Progressive Democratic Tribune [8]

Morocco Istiqlal Party Youth Youth wing of the Istiqlal Party

USFP Jeunesse Ittihadiya Youth wing of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces

Jeunesse Socialiste Youth wing of the Party of Progress and Socialism

Palestine General Union of Palestine Students [8]

Palestinian Democratic Youth Union Youth wing of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine [8]

Syria Union of Democratic Youth of Syria-Khaled Baghdash Youth wing of the Syrian Communist Party [8]

Syrian Democratic Youth Union Youth wing of the Syrian Unified Communist Party

Revolutionary Youth Union Youth wing of the Ba'ath Party

Kuwait Democratic Youth Union Youth wing of the KPM

Former members

• Afghanistan - Democratic Youth Organization of Afghanistan

• Albania - Bashkimi i Rinisë së Punës së Shqipërisë

• Argentina - Juventud Intrasigente Argentina

• Argentina - Juventud Socialista Auténtica

• Australia - Eureka Youth League

• Belgium - Graffiti Jeugendsdienst

• Belgium - Jeunesse Communiste de Belgique

• Bolivia - Confederación Universitaria Boliviana

• Brazil - Juventude do PCB

• Bulgaria - Dimitrov Komsomol

• Byelorussian SSR - Leninist Communist Youth Union of Belarus

• Cambodia - People's Revolutionary Youth Union of Kampuchea

• Chile - Juventud de la Izquierda Cristiana de Chile

• Chile - Juventud del MIR

• Chile - Juventud Rebelde Miguel Enríquez

• Chile - Unión de Jóvenes Socialistas

• China - Communist Youth League of China

• China - All-China Youth Federation

• Colombia - Federación Juvenil Obrera

• Colombia - Juventud de la Alianza Nacional Popular

• Colombia - Juventud del Poder Popular

• Colombia - Unión Nacional de los Estudiantes Secundarios

• Colombia - Unión de Jóvenes Patriotas

• Congo - Union de la jeunesse congolaise, Republic of Congo

• Costa Rica - Juventud del Pueblo Costarriquense

• Costa Rica - Juventudes Patrióticas

• Costa Rica - Juventud Vanguardista Costarriquense

• Czechoslovakia - Svaz Mládeže, Czechoslovakia

• Dominican Republic - Juventud Revolucionaria Dominicana

• Dominican Republic - Unión Democrática Orlando Martínez

• Ecuador - Departamento Juvenil del Central de Trabajadores de Ecuador

• Ecuador - Juventud Comunista de Ecuador

• El Salvador - Asociación General de Estudiantes Universitarios de El Salvador

• Faroe Islands - Færøske Socialister

• Finland - Democratic Youth League of Finland

• Finland - Finnish Union of Democratic Pioneers

• Germany - Socialist Youth League Karl Liebknecht

• East Germany - Free German Youth

• Greece - Greek Communist Youth (Internal)

• Guadeloupe - Union de la Jeunesse Communiste Guadeloupe

• France - Union nationale des étudiants de france-Solidarité Etudiante

• Guatemala - Juventud Patriótica del Trabajo

• Guyana - Young Socialist Movement

• Haiti - Jeunesse Communiste de Haiti

• Honduras - Federación de la Juventud Comunista

• Iceland - Revolutionary Communist Youth League

• Indonesia - People's Youth (Indonesia)

• Italy - Italian Communist Youth Federation

• Jamaica - Young Communist League of the Workers' Party (Workers Party of Jamaica)

• Luxembourg - Jeunesse Communiste Luxembourgoise

• Martinique - Union de la Jeunesse Communiste Martinique

• Mexico - Frente Juvenil Revolucionario

• Mexico - Juventud Socialista de los Trabajadores

• Mongolia - Revolutionary Youth League (REVSOMOL)

• Netherlands - Algemeen Nederlands Jeugd Verbond

• Hungary - Kommunista Ifjúsági Szövetség

• Panama - Juventud del PRD

• Panama - Juventud Popular Revolucionaria

• Paraguay - Federación Juvenil Comunista de Paraguay

• Peru - CGTP Sección Juvenil

• Peru - Juventud Aprista Peruana

• Peru - Juventud Mariateguista

• Poland - Związek Socjalistycznej Młodzieży Polskiej

• Puerto Rico - Federación Universitaria para la Indpendencia

• Puerto Rico - Juventud Comunista de Puerto Rico

• Puerto Rico - Juventud Socialista de Puerto Rico

• San Marino - Federazione Giovanile Comunista San Marino

• Sri Lanka - Congress of Sama Samaja Youth Leagues

• Sri Lanka - Federation of Communist and Progressive Youth

• Saint Vincent and the Grenadines - Vanguard Youth Organization

• Surinam - National Youth Movement

• Sweden - Ung Vänster (1975–1992)

• Switzerland - Jeunesse Communiste Suisse

• Tunisia - Destourian Youth

• Turkey - İlerici Gençler Derneği

• United States - Young Communist League USA

• United States - Young Socialist Alliance

• Uruguay - Juventud Socialista del Uruguay

• Soviet Union - Committee of Youth Organizations of the USSR

• Soviet Union - All-Union Leninist Young Communist League (Komsomol)

• Venezuela - Juventud Socialista-MEP

• Japan - Democratic Youth League of Japan

Observers

• Youth for Communist Rebirth In France (Youth of the Pole of Communist Rebirth in France)

• Communist Youth Movement (Youth of the New Communist Party of the Netherlands)

• Communist Youth of Luxemburg (Refounded youth organisation of the Communist Party of Luxembourg), Luxembourg

• Revolutionary Communist Youth (Youth organization of the Communist Party), Sweden

See also

• Active measures

• Christian Peace Conference

• International Association of Democratic Lawyers

• International Federation of Resistance Fighters – Association of Anti-Fascists

• International Organization of Journalists

• International Union of Students

• Women's International Democratic Federation

• World Federation of Scientific Workers

• World Federation of Trade Unions

• World Peace Council

References

1. Richard Felix Staar, Foreign policies of the Soviet Union, Hoover Press, 1991, ISBN 0-8179-9102-6, p.84

2. Jump up to:a b c The cultural Cold War in Western Europe, 1945-1960. Giles Scott-Smith, Hans Krabbendam. p. 169

3. A century of spies: intelligence in the twentieth century. Jeffrey T. Richelson. p. 252

4. Soviet foreign policy in a changing world, Volume 1986. Robbin Frederick Laird, Erik P. Hoffmann. p. 211

5. Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia, Volume 1. Bernard A. Cook. p. 212

6. https://dialogos.com.cy/rik-kai-ta-ypol ... -tis-podn/

7. "Approved Political Declaration Of the 19th Assembly of WFDY (1).pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

8. "Members". wfdy.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016.

9. United States Congress, House Committee on Un-American Activities (1956), Soviet Total War: "Historic Mission" of Violence and Deceit, 1–2, U.S. Government Printing Office, pp. 589–90

External links

• Official website

Czechoslovakia Prague 17,000 71 "Youth Unite, Forward for Lasting Peace!"

Czechoslovakia Prague 17,000 71 "Youth Unite, Forward for Lasting Peace!" Hungary Budapest 20,000 82 "Youth Unite, Forward for Lasting Peace, Democracy, National Independence and a better future for the people"

Hungary Budapest 20,000 82 "Youth Unite, Forward for Lasting Peace, Democracy, National Independence and a better future for the people" East Germany East Berlin 26,000 104 "For Peace and Friendship – Against Nuclear Weapons"

East Germany East Berlin 26,000 104 "For Peace and Friendship – Against Nuclear Weapons" Romania Bucharest 30,000 111 "No! Our generation will not serve death and destruction!"

Romania Bucharest 30,000 111 "No! Our generation will not serve death and destruction!" Poland Warsaw 30,000 114 "For Peace and Friendship – Against the Aggressive Imperialist Pacts"

Poland Warsaw 30,000 114 "For Peace and Friendship – Against the Aggressive Imperialist Pacts" Soviet Union Moscow 34,000 131 "For Peace and Friendship"

Soviet Union Moscow 34,000 131 "For Peace and Friendship" Austria Vienna 18,000 112 "For Peace and Friendship and Peaceful Coexistence"

Austria Vienna 18,000 112 "For Peace and Friendship and Peaceful Coexistence" Finland Helsinki 18,000 137 "For Peace and Friendship"

Finland Helsinki 18,000 137 "For Peace and Friendship" Bulgaria Sofia 20,000 138 "For Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

Bulgaria Sofia 20,000 138 "For Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" East Germany East Berlin 25,600 140 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

East Germany East Berlin 25,600 140 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" Cuba Havana 18,500 145 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

Cuba Havana 18,500 145 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" Soviet Union Moscow 26,000 157 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

Soviet Union Moscow 26,000 157 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" North Korea Pyongyang 22,000 177 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

North Korea Pyongyang 22,000 177 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" Cuba Havana 12,325 136 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship"

Cuba Havana 12,325 136 "For Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship" Algeria Algiers 6,500 110 "Let’s Globalize the Struggle For Peace, Solidarity, Development, Against Imperialism"

Algeria Algiers 6,500 110 "Let’s Globalize the Struggle For Peace, Solidarity, Development, Against Imperialism" Venezuela Caracas 17,000 144 "For Peace and Solidarity, We Struggle Against Imperialism and War"

Venezuela Caracas 17,000 144 "For Peace and Solidarity, We Struggle Against Imperialism and War" South Africa Pretoria 15,000 126 "Let's Defeat Imperialism, for a World of Peace, Solidarity and Social Transformation!"

South Africa Pretoria 15,000 126 "Let's Defeat Imperialism, for a World of Peace, Solidarity and Social Transformation!" Russia Sochi 30,000 185[5] "For peace, solidarity and social justice, we struggle against imperialism. Honoring our past, we build the future!"

Russia Sochi 30,000 185[5] "For peace, solidarity and social justice, we struggle against imperialism. Honoring our past, we build the future!"