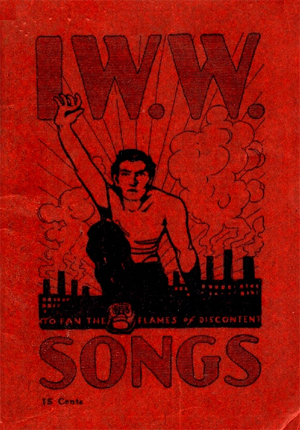

Industrial Workers of the World [Wobblies]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/18/20

IWW

Full name: Industrial Workers of the World

Founded: June 27, 1905; 114 years ago[1][2]

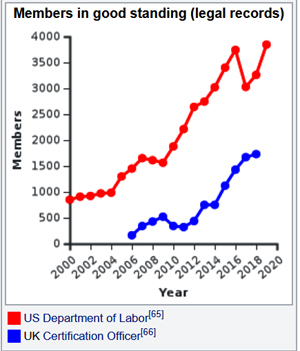

Members: Increase 5,875[a]

Journal: Industrial Worker

Key people: § Notable members

Office location: Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

Country: International

Website: http://www.iww.org

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in 1905 in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States. The union combines general unionism with industrial unionism, as it is a general union, subdivided between the various industries which employ its members. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as "revolutionary industrial unionism", with ties to both socialist[4] and anarchist labor movements.

In the 1910s and early 1920s, the IWW achieved many of their short-term goals, particularly in the American West, and cut across traditional guild and union lines to organize workers in a variety of trades and industries. At their peak in August 1917, IWW membership was more than 150,000, with active wings in the United States, Canada, and Australia.[5] The extremely high rate of IWW membership turnover during this era (estimated at 133% per decade) makes it difficult for historians to state membership totals with any certainty, as workers tended to join the IWW in large numbers for relatively short periods (e.g., during labor strikes and periods of generalized economic distress).[6]

Due to several factors, membership declined dramatically in the late 1910s and 1920s. There were conflicts with other labor groups, particularly the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which regarded the IWW as too radical, while the IWW regarded the AFL as too conservative and dividing workers by craft.[7] Membership also declined due to government crackdowns on radical, anarchist and socialist groups during the First Red Scare after World War I. In Canada the IWW was outlawed by the federal government.

Probably the most decisive factor in the decline in IWW membership and influence, however, was a 1924 schism in the organization, from which the IWW never fully recovered.[7][8]

The IWW promotes the concept of "One Big Union", and contends that all workers should be united as a social class to supplant capitalism and wage labor with industrial democracy.[9] They are known for the Wobbly Shop model of workplace democracy, in which workers elect their managers[10] and other forms of grassroots democracy (self-management) are implemented. IWW membership does not require that one work in a represented workplace,[11] nor does it exclude membership in another labor union.[12]

In 2012, the IWW moved its General Headquarters offices to 2036 West Montrose in Chicago.[13] The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain.[14]

History 1905–1950

Main article: Industrial Workers of the World organizational evolution

Founding

Big Bill Haywood and office workers in the IWW General Office, Chicago, summer 1917.

The IWW was founded in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States in June 1905. A convention was held of 200 socialists, anarchists, Marxists (primarily members of the Socialist Party of America and Socialist Labor Party) radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the Western Federation of Miners) who strongly opposed the policies of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The IWW opposed the American Federation of Labor's acceptance of capitalism and its refusal to include unskilled workers in craft unions.[15]

The convention had taken place on June 24, 1905, and was referred to as the "Industrial Congress" or the "Industrial Union Convention". It would later be known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW.[6]:67 It later became considered one of the most important events in the history of industrial unionism.[6]:67

The IWW's founders included William D. ("Big Bill") Haywood, James Connolly, Daniel De Leon, Eugene V. Debs, Thomas Hagerty, Lucy Parsons, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones, Frank Bohn, William Trautmann, Vincent Saint John, Ralph Chaplin, and many others.

The IWW aimed to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class; its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all", which improved upon the Knights of Labor's creed, "an injury to one is the concern of all" which was at its most popular in the 1880s. In particular, the IWW was organized because of the belief among many unionists, socialists, anarchists, Marxists, and radicals that the AFL not only had failed to effectively organize the U.S. working class, but it was causing separation rather than unity within groups of workers by organizing according to narrow craft principles. The Wobblies believed that all workers should organize as a class, a philosophy which is still reflected in the Preamble to the current IWW Constitution:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth.

We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

Instead of the conservative motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work," we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, "Abolition of the wage system."

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.[9]

The first IWW charter in Canada, Vancouver Industrial Mixed Union no.322, May 5, 1906.

The Wobblies, as they were informally known, differed from other union movements of the time by promotion of industrial unionism, as opposed to the craft unionism of the American Federation of Labor. The IWW emphasized rank-and-file organization, as opposed to empowering leaders who would bargain with employers on behalf of workers. The early IWW chapters' consistently refused to sign contracts, which they believed would restrict workers' abilities to aid each other when called upon. Though never developed in any detail, Wobblies envisioned the general strike as the means by which the wage system would be overthrown and a new economic system ushered in, one which emphasized people over profit, cooperation over competition.

One of the IWW's most important contributions to the labor movement and broader push towards social justice was that, when founded, it was the only American union to welcome all workers, including women, immigrants, African Americans and Asians, into the same organization. Many of its early members were immigrants, and some, such as Carlo Tresca, Joe Hill and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, rose to prominence in the leadership. Finns formed a sizeable portion of the immigrant IWW membership. "Conceivably, the number of Finns belonging to the I.W.W. was somewhere between five and ten thousand."[16] The Finnish-language newspaper of the IWW, Industrialisti, published in Duluth, Minnesota, a center of the mining industry, was the union's only daily paper. At its peak, it ran 10,000 copies per issue. Another Finnish-language Wobbly publication was the monthly Tie Vapauteen ("Road to Freedom"). Also of note was the Finnish IWW educational institute, the Work People's College in Duluth, and the Finnish Labour Temple in Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada, which served as the IWW Canadian administration for several years. Further, many Swedish immigrants, particularly those blacklisted after the 1909 Swedish General Strike, joined the IWW and set up similar cultural institutions around the Scandinavian Socialist Clubs. This in turn exerted a political influence on the Swedish labour movement's left, that in 1910 formed the Syndicalist union SAC which soon contained a minority seeking to mimick the tactics and strategies of the IWW.[17] One example of the union's commitment to equality was Local 8, a longshoremen's branch in Philadelphia, one of the largest ports in the nation in the WWI era. Led by Ben Fletcher, an African American, Local 8 had more than 5,000 members, the majority of whom were African American, along with more than a thousand immigrants (primarily Lithuanians and Poles), Irish Americans, and numerous white ethnics.

Divide on political action or direct action

Main article: Industrial Workers of the World philosophy and tactics

In 1908 a group led by Daniel DeLeon argued that political action through DeLeon's Socialist Labor Party (SLP) was the best way to attain the IWW's goals. The other faction, led by Vincent Saint John, William Trautmann, and Big Bill Haywood, believed that direct action in the form of strikes, propaganda, and boycotts was more likely to accomplish sustainable gains for working people; they were opposed to arbitration and to political affiliation. Haywood's faction prevailed, and De Leon and his supporters left the organization, forming their own version of the IWW. The SLP's "Yellow IWW" eventually took the name Workers' International Industrial Union, which was disbanded in 1924.

The black cat symbol, created by IWW member Ralph Chaplin, is often used to signify sabotage or wildcat strikes.

Organizing

A Wobbly membership card, or "red card"

"The few own the many because they possess the means of livelihood of all ... The country is governed for the richest, for the corporations, the bankers, the land speculators, and for the exploiters of labor. The majority of mankind are working people. So long as their fair demands – the ownership and control of their livelihoods – are set at naught, we can have neither men's rights nor women's rights. The majority of mankind is ground down by industrial oppression in order that the small remnant may live in ease."

— Helen Keller, IWW member, 1911[18]

The IWW first attracted attention in Goldfield, Nevada in 1906 and during the Pressed Steel Car Strike of 1909[19] at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania. Further fame was gained later that year, when they took their stand on free speech. The town of Spokane, Washington, had outlawed street meetings, and arrested Elizabeth Gurley Flynn,[20] a Wobbly organizer, for breaking this ordinance. The response was simple but effective: when a fellow member was arrested for speaking, large numbers of people descended on the location and invited the authorities to arrest all of them, until it became too expensive for the town. In Spokane, over 500 people went to jail and four people died. The tactic of fighting for free speech to popularize the cause and preserve the right to organize openly was used effectively in Fresno, Aberdeen, and other locations. In San Diego, although there was no particular organizing campaign at stake, vigilantes supported by local officials and powerful businessmen mounted a particularly brutal counter-offensive.

1914 IWW demonstration in New York City

By 1912 the organization had around 25,000 members,[21] concentrated in the Northwest, among dock workers, agricultural workers in the central states, and in textile and mining areas. The IWW was involved in over 150 strikes, including the Lawrence textile strike (1912), the Paterson silk strike (1913) and the Mesabi range (1916). They were also involved in what came to be known as the Wheatland Hop Riot on August 3, 1913.

Geography

In its first decades, the IWW created more than 900 unions located in more than 350 cities and towns in 38 states and territories of the United States and 5 Canadian provinces.[22] Throughout the country, there were 90 newspapers and periodicals affiliated with the IWW, published in 19 different languages. Members of the IWW were active throughout the country and were involved in the Seattle General Strike,[23] were arrested or killed in the Everett Massacre,[24] organized among Mexican workers in the Southwest,[25] became a largest and powerful longshoremen's union in Philadelphia,[26] and more.

IWW versus AFL Carpenters, Goldfield, Nevada, 1907

The IWW assumed a prominent role in 1906 and 1907, in the gold-mining boom town of Goldfield, Nevada. At that time, the Western Federation of Miners was still an affiliate of the IWW (the WFM withdrew from the IWW in the summer of 1907). In 1906, the IWW became so powerful in Goldfield that it could dictate wages and working conditions.

Resisting IWW domination was the AFL-affiliated Carpenters Union. In March 1907, the IWW demanded that the mines deny employment to AFL Carpenters, which led mine owners to challenge the IWW. The mine owners banded together and pledged not to employ any IWW members. The mine and business owners of Goldfield staged a lockout, vowing to remain shut until they had broken the power of the IWW. The lockout prompted a split within the Goldfield workforce, between conservative and radical union members.[27]

The mine owners persuaded the Nevada governor to ask for federal troops. Under the protection of federal troops, the mine owners reopened the mines with non-union labor, breaking the influence of the IWW in Goldfield.

The Haywood trial and the exit of the Western Federation of Miners

Leaders of the Western Federation of Miners such as Bill Haywood and Vincent St. John were instrumental in forming the IWW, and the WFM affiliated with the new union organization shortly after the IWW was formed. The WFM became the IWW's "mining section." However, many in the rank and file of the WFM were uncomfortable with the open radicalism of the IWW, and wanted the WFM to maintain its independence. Schisms between the WFM and IWW had emerged at the annual IWW convention in 1906, when a majority of WFM delegates walked out.[6]

When WFM executives Bill Haywood, George Pettibone, and Charles Moyer were accused of complicity in the murder of former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg, the IWW used the case to raise funds and support, and paid for the legal defense. However, even the not guilty verdicts worked against the IWW, because the IWW was deprived of martyrs, and at the same time, a large portion of the public remained convinced of the guilt of the accused.[28] The trials caused a bitter split between Haywood and Moyer. The Haywood trial also provoked a reaction within the WFM against violence and radicalism. In the summer of 1907, the WFM withdrew from the IWW, Vincent St. John left the WFM to spend his time organizing the IWW.

Bill Haywood for a time remained a member of both organizations. His murder trial had made Haywood a celebrity, and he was in demand as a speaker for the WFM. However, his increasingly radical speeches became more at odds with the WFM, and in April 1908, the WFM announced that the union had ended Haywood's role as a union representative. Haywood left the WFM, and devoted all his time to organizing for the IWW.[6]:216–217

Historian Vernon H. Jensen has asserted that the IWW had a "rule or ruin" policy, under which it attempted to wreck local unions which it could not control. From 1908 to 1921, Jensen and others have written, the IWW attempted to win power in WFM locals which had once formed the federation's backbone. When it could not do so, IWW agitators undermined WFM locals, which caused the national union to shed nearly half its membership.[29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

IWW versus the Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners left the IWW in 1907, but the IWW wanted the WFM back. The WFM had made up about a third of the IWW membership, and the western miners were tough union men, and good allies in a labor dispute. In 1908, Vincent St. John tried to organize a stealth takeover of the WFM. He wrote to WFM organizer Albert Ryan, encouraging him to find reliable IWW sympathizers at each WFM local, and have them appointed delegates to the annual convention by pretending to share whatever opinions of that local needed to become a delegate. Once at the convention, they could vote in a pro-IWW slate. St. Vincent promised: “… once we can control the officers of the WFM for the IWW, the big bulk of the membership will go with them.” But the takeover did not succeed.[36]

In 1914, Butte, Montana, erupted into a series of riots as miners dissatisfied with the Western Federation of Miners local at Butte formed a new union, and demanded that all miners join the new union, or be subject to beatings or worse. Although the new rival union had no affiliation with the IWW, it was widely seen as IWW-inspired. The leadership of the new union contained many who were members of the IWW, or agreed with the IWW's methods and objectives. However, the new union failed to supplant the WFM, and the ongoing fight between the two factions had the result that the copper mines of Butte, which had long been a union stronghold for the WFM, became open shops, and the mine owners recognized no union from 1914 until 1934.[37]

IWW versus United Mine Workers, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1916

The IWW clashed with the United Mine Workers union in April 1916, when the IWW picketed the anthracite mines around Scranton, Pennsylvania, intending, by persuasion or force, to keep UMWA members from going to work. The IWW considered the UMWA too reactionary, because the United Mine Workers negotiated contracts with the mine owners for fixed time periods; the IWW considered that contracts hindered their revolutionary goals. In what a contemporary writer pointed out was a complete reversal of their usual policy, UMWA officials called for police to protect United Mine Workers members who wished to cross the picket lines. The Pennsylvania State Police arrived in force, prevented picket line violence, and allowed the UMWA members to peacefully pass through the IWW picket lines.[6][38]

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO) organized more than a hundred thousand migratory farm workers throughout the Midwest and western United States,[39] often signing up and organizing members in the field, in rail yards and in hobo jungles. During this time, the IWW member became synonymous with the hobo riding the rails; migratory farmworkers could scarcely afford any other means of transportation to get to the next jobsite. Railroad boxcars, called "side door coaches" by the hobos, were frequently plastered with silent agitators from the IWW.

Building on the success of the AWO, the IWW's Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) used similar tactics to organize lumberjacks and other timber workers, both in the deep South and the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, between 1917 and 1924. The IWW lumber strike of 1917 led to the eight-hour day and vastly improved working conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Even though mid-century historians would give credit to the US Government and "forward thinking lumber magnates" for agreeing to such reforms, an IWW strike forced these concessions.[40]

From 1913 through the mid-1930s, the IWW's Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union (MTWIU), proved a force to be reckoned with and competed with AFL unions for ascendance in the industry. Given the union's commitment to international solidarity, its efforts and success in the field come as no surprise. Local 8 of the Marine Transport Workers was led by Ben Fletcher, who organized predominantly African-American longshoremen on the Philadelphia and Baltimore waterfronts, but other leaders included the Swiss immigrant Walter Nef, Jack Walsh, E.F. Doree, and the Spanish sailor Manuel Rey. The IWW also had a presence among waterfront workers in Boston, New York City, New Orleans, Houston, San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Eureka, Portland, Tacoma, Seattle, Vancouver as well as in ports in the Caribbean, Mexico, South America, Australia, New Zealand, Germany and other nations. IWW members played a role in the 1934 San Francisco general strike and the other organizing efforts by rank-and-filers within the International Longshoremen's Association up and down the West Coast.

Wobblies also played a role in the sit-down strikes and other organizing efforts by the United Auto Workers in the 1930s, particularly in Detroit, though they never established a strong union presence there.

Where the IWW did win strikes, such as in Lawrence, they often found it hard to hold onto their gains. The IWW of 1912 disdained collective bargaining agreements and preached instead the need for constant struggle against the boss on the shop floor. It proved difficult, however, to maintain that sort of revolutionary enthusiasm against employers. In Lawrence, the IWW lost nearly all of its membership in the years after the strike, as the employers wore down their employees' resistance and eliminated many of the strongest union supporters. In 1938, the IWW voted to allow contracts with employers,[41] so long as they would not undermine any strike.

Government suppression

Joseph J. Ettor, who had been arrested in 1912, giving a speech to barbers on strike

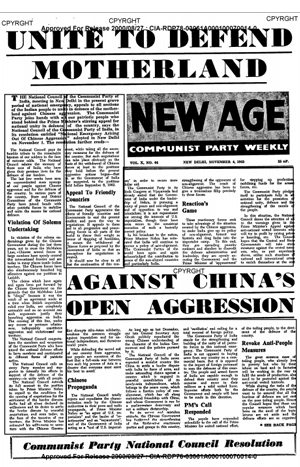

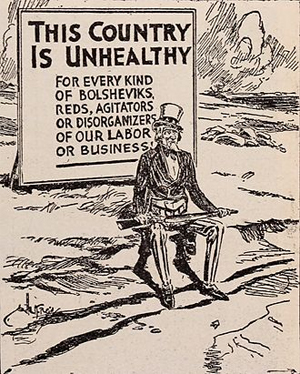

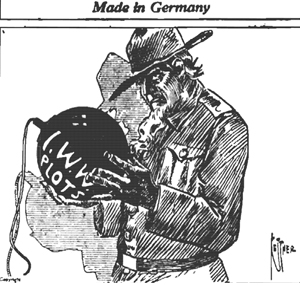

A newspaper editorial cartoon from 1917, critical of the IWW's antiwar stance during World War I

Anti-socialist cartoon in a railroad-sponsored magazine, 1912

The IWW's efforts were met with "unparalleled" resistance from Federal, state and local governments in America;[7] from company management and labor spies, and from groups of citizens functioning as vigilantes. In 1914, Wobbly Joe Hill (born Joel Hägglund) was accused of murder in Utah and, on what many regarded as flimsy evidence, was executed in 1915.[42][43] On November 5, 1916, at Everett, Washington, a group of deputized businessmen led by Sheriff Donald McRae attacked Wobblies on the steamer Verona, killing at least five union members[44] (six more were never accounted for and probably were lost in Puget Sound). Two members of the police force — one a regular officer and another a deputized citizen from the National Guard Reserve — were killed, probably by "friendly fire".[45] At least five Everett civilians were wounded.[46]

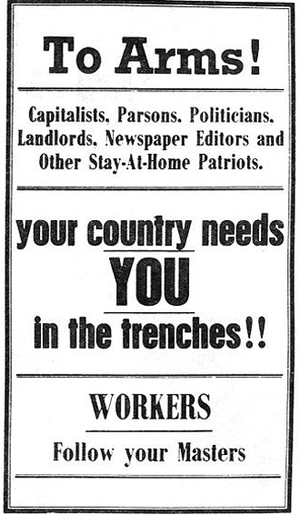

Many IWW members opposed United States participation in World War I. The organization passed a resolution against the war at its convention in November 1916.[47]:241 This echoed the view, expressed at the IWW's founding convention, that war represents struggles among capitalists in which the rich become richer, and the working poor all too often die at the hands of other workers.

An IWW newspaper, the Industrial Worker, wrote just before the U.S. declaration of war: "Capitalists of America, we will fight against you, not for you! There is not a power in the world that can make the working class fight if they refuse." Yet when a declaration of war was passed by the U.S. Congress in April 1917, the IWW's general secretary-treasurer Bill Haywood became determined that the organization should adopt a low profile in order to avoid perceived threats to its existence. The printing of anti-war stickers was discontinued, stockpiles of existing anti-war documents were put into storage, and anti-war propagandizing ceased as official union policy. After much debate on the General Executive Board, with Haywood advocating a low profile and GEB member Frank Little championing continued agitation, Ralph Chaplin brokered a compromise agreement. A statement was issued that denounced the war, but IWW members were advised to channel their opposition through the legal mechanisms of conscription. They were advised to register for the draft, marking their claims for exemption "IWW, opposed to war."[47]:242–244

In spite of the IWW moderating its vocal opposition, the IWW's antiwar stance made it highly unpopular. Frank Little, the IWW's most outspoken war opponent, was lynched in Butte, Montana, in August 1917, just four months after war had been declared.

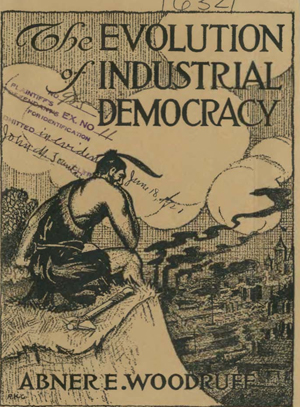

Cover of The Evolution of Industrial Democracy by Abner E. Woodruff, initialed by illustrator Ralph Hosea Chaplin, published by IWW. Notably stamped as evidence used in a trial.

During World War I the U.S. government moved strongly against the IWW. On September 5, 1917, U.S. Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on dozens of IWW meeting halls across the country.[30]:406 Minutes books, correspondence, mailing lists, and publications were seized, with the U.S. Department of Justice removing five tons of material from the IWW's General Office in Chicago alone.[30]:406 This seized material was scoured for possible violations of the Espionage Act of 1917 and other laws, with a view to future prosecution of the organization's leaders, organizers, and key activists.

Based in large measure on the documents seized September 5, one hundred and sixty-six IWW leaders were indicted by a Federal Grand Jury in Chicago for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes, under the new Espionage Act.[30]:407 One hundred and one went on trial en masse before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1918. Their lawyer was George Vanderveer of Seattle.[48] They were all convicted — including those who had not been members of the union for years — and given prison terms of up to twenty years. Sentenced to prison by Judge Landis and released on bail, Haywood fled to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic where he remained until his death.

In 1917, during an incident known as the Tulsa Outrage, a group of black-robed Knights of Liberty tarred and feathered seventeen members of the IWW in Oklahoma. The attack was cited as revenge for the Green Corn Rebellion, a preemptive attack caused by fear of an impending attack on the oil fields and as punishment for not supporting the war effort. The IWW members had been turned over to the Knights of Liberty by local authorities after they were beaten, arrested at their headquarters and convicted of the crime of vagrancy. Five other men who testified in defense of the Wobblies were also fined by the court and subjected to the same torture and humiliations at the hands of the Knights of Liberty.[49][50][51][52][53]

In 1919, an Armistice Day parade by the American Legion in Centralia, Washington, turned into a fight between legionnaires and IWW members in which four legionnaires and a Centralia deputy sheriff were shot dead. Which side initiated the violence of the Centralia massacre is disputed. A number of IWWs were arrested, one of whom, Wesley Everest, was lynched by a mob that night.[54]

Members of the IWW were prosecuted under various State and federal laws and the 1920 Palmer Raids singled out the foreign-born members of the organization.

Organizational schism and afterwards

IWW quickly recovered from the setbacks of 1919 and 1920, with membership peaking in 1923 (58,300 estimated by dues paid per capita, though membership was likely much higher as the union tolerated delinquent members).[55] But recurring internal debates, especially between those who sought either to centralize or decentralize the organization, ultimately brought about the IWW's 1924 schism.[56]

At the beginning of the 1949 Smith Act trials, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was disappointed when prosecutors indicted fewer CPUSA members than he had hoped, and – recalling the arrests and convictions of over one hundred IWW leaders in 1917 – complained to the Justice Department, stating, "the IWW was crushed and never revived, similar action at this time would have been as effective against the Communist Party."

Activity after World War II

1950–2000

Taft–Hartley Act

An injury to one is an injury to all.

After the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1946 by Congress, which called for the removal of Communist union leadership, the IWW experienced a loss of membership as differences of opinion occurred over how to respond to the challenge. In 1949, US Attorney General Tom C. Clark[57] placed the IWW on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations[58] in the category of "organizations seeking to change the government by unconstitutional means" under Executive Order 9835, which offered no means of appeal, and which excluded all IWW members from Federal employment and federally subsidized housing programs (this order was revoked by Executive Order 10450 in 1953).

At this time, the Cleveland local of the Metal and Machinery Workers Industrial Union (MMWIU) was the strongest IWW branch in the United States. Leading figures such as Frank Cedervall, who had helped build the branch up for over ten years, were concerned about the possibility of raiding from AFL-CIO unions if the IWW had its legal status as a union revoked. In 1950, Cedervall led the 1500-member MMWIU national organization to split from the IWW, as the Lumber Workers Industrial Union had almost thirty years earlier. Unfortunately for the MMWIU, this act would not save it. Despite its brief affiliation with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, it would face serious raiding from AFL and CIO and would be defunct by the late 1950s, less than ten years after separating from the IWW.[59]

The loss of the MMWIU, at the time the IWW's largest industrial union, was almost a deathblow to the IWW. The union's membership fell to its lowest level in the 1950s during the Second Red Scare, and by 1955, the union's fiftieth anniversary, it was near extinction, though it still appeared on government lists of Communist-led groups.[60]

1960s rejuvenation

The 1960s civil rights movement, anti-war protests, and various university student movements brought new life to the IWW, albeit with many fewer new members than the great organizing drives of the early part of the 20th century.

The first signs of new life for the IWW in the 1960s would be organizing efforts among students in San Francisco and Berkeley, which were hotbeds of student radicalism at the time. This targeting of students would result in a Bay Area branch of the union with over a hundred members in 1964, almost as many as the union's total membership in 1961. Wobblies old and new would unite for one more "free speech fight": Berkeley's Free Speech Movement. Riding on this high, the decision in 1967 to allow college and university students to join the Education Workers Industrial Union (IU 620) as full members spurred campaigns in 1968 at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.[61]:13 The IWW would send representatives to Students for a Democratic Society conventions in 1967, 1968, and 1969, and as the SDS collapsed into infighting, the IWW would gain members who were fleeing this discord. These changes would have a profound effect on the union, which by 1972 would have sixty-seven percent of members under the age of thirty, with a total of nearly five hundred members.[61]:14

The IWW's links to the 60s counterculture led to organizing campaigns at counterculture businesses, as well as a wave of over two dozen co-ops affiliating with the IWW under its Wobbly Shop model in the 1960s to 1980s. These businesses were primarily in printing, publishing, and food distribution; from underground newspapers and radical print shops to community co-op grocery stores. Some of the printing and publishing industry co-ops and job shops included Black & Red (Detroit), Glad Day Press (New York),[61]:17 RPM Press (Michigan),[61]:17 New Media Graphics (Ohio),[61]:17 Babylon Print (Wisconsin),[61]:17 Hill Press (Illinois),[61]:17 Lakeside (Madison, Wisconsin), Harbinger (Columbia, South Carolina), Eastown Printing in Grand Rapids, Michigan (where the IWW negotiated a contract in 1978),[61]:17 and La Presse Populaire (Montréal). This close affiliation with radical publishers and printing houses sometimes led to legal difficulties for the union, such as when La Presse Populaire was shut down in 1970 by provincial police for publishing pro-FLQ materials, which were banned at the time under an official censorship law. Also in 1970, the San Diego, California, "street journal" El Barrio became an official IWW shop. In 1971 its office was attacked by an organization calling itself the Minutemen, and IWW member Ricardo Gonzalves was indicted for criminal syndicalism along with two members of the Brown Berets.[60]

These ties to anti-authoritarian and radical artistic and literary currents would link the IWW even more heavily to the 60s counterculture, exemplified by the publication in Chicago in the 1960s of Rebel Worker by the surrealists Franklin and Penelope Rosemont. One edition was published in London with Charles Radcliffe, who went on to become involved with the Situationist International. By the 1980s, the Rebel Worker was being published as an official organ again, from the IWW's headquarters in Chicago, and the New York area was publishing a newsletter as well.