Part 2 of 2

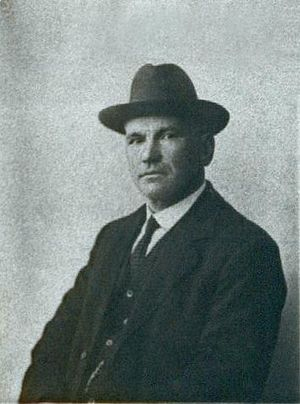

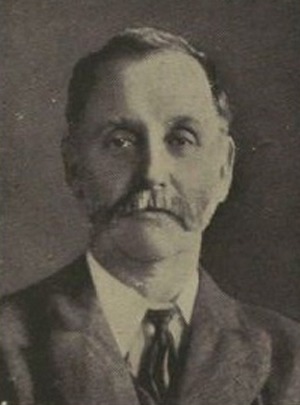

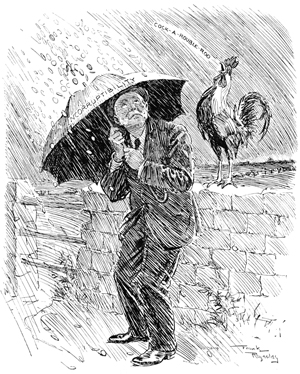

Party leaderAlthough defeated in the election, Henderson remained the party leader while Lansbury headed the Labour group in parliament—the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). In October 1932 Henderson resigned and Lansbury succeeded him.[1] In most historians' reckonings, Lansbury led his small parliamentary force with skill and flair. He was also, says Shepherd, an inspiration to the dispirited Labour rank and file.[127] As leader he began the process of reforming the party's organisation and machinery, efforts which resulted in considerable by-election and municipal election successes—including control of the LCC under Herbert Morrison in 1934.[4][128] According to Blythe, Lansbury "represented political hope and decency to the three million unemployed."[129] During this period Lansbury published his political credo, My England (1934), which envisioned a future socialist state achieved by a mixture of revolutionary and evolutionary methods.[130]I believe that force never has and never will bring permanent peace and goodwill in the world ... God intends us to live peacefully and quietly with one another. If some people do not allow us to do so, I am ready to stand as the early Christians did, and say, this is our faith, this is where we stand, and, if necessary, this is where we will die.

(From Lansbury's speech to the 1935 Labour Party conference)[131]

The small Labour group in parliament had little influence over economic policy; Lansbury's term as leader was dominated by foreign affairs and disarmament, and by policy disagreements within the Labour movement. The official party position was based on collective security through the League of Nations and on multilateral disarmament. Lansbury, supported by many in the PLP, adopted a position of Christian pacifism, unilateral disarmament and the dismantling of the British Empire.[132] Under his influence the party's 1933 conference passed resolutions calling for the "total disarmament of all nations", and pledged to take no part in war.[133] Pacifism became temporarily popular in the country; on 9 February 1933 the Oxford Union voted by 275 to 153 that it would "in no circumstances fight for its King and Country", and the Fulham East by-election in October 1933 was easily won by a Labour candidate committed to full disarmament.[134] Lansbury sent a message to the constituency in his position as Labour Leader: "I would close every recruiting station, disband the Army and disarm the Air Force. I would abolish the whole dreadful equipment of war and say to the world: “Do your worst”."[135] October 1934 saw the emergence of the Peace Pledge Union. In response to the Peace Pledge Union, the League of Nations Union conducted the 1934–35 Peace Ballot, an unofficial public referendum, which produced massive majorities in support of the League of Nations, multilateral disarmament, and conflict resolution through non-military means - though crucially, a three-fold majority supported military measures as a last resort. Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler had come to power in Germany, and had withdrawn from the international Conference on Disarmament in Geneva. Blythe observes that Britain's noisy flirtations with pacifism "drowned out the sounds from German dockyards", as German rearmament began.[134]

As fascism and militarism advanced in Europe, Lansbury's pacifist stance drew criticism from the trades union elements of his party—who controlled the majority of party conference votes. Walter Citrine, the TUC general secretary, commented that Lansbury "thinks the country should be without defence of any kind ... it certainly isn't our policy."[136] The party's 1935 annual conference took place in Brighton during October, under the shadow of Italy's impending invasion of Abyssinia. The national executive had tabled a resolution calling for sanctions against Italy, which Lansbury opposed as a form of economic warfare. His speech—a passionate exposition of the principles of Christian pacifism—was well received by the delegates, but immediately afterwards his position was destroyed by Ernest Bevin, the Transport and General Workers' Union leader. Bevin attacked Lansbury for putting his private beliefs before a policy, agreed by all the party's main institutions, to oppose fascist aggression,[137] and accused him of "hawking your conscience round from body to body asking to be told what to do with it".[138] Union support ensured that the sanctions resolution was carried by a huge majority; Lansbury, realising that a Christian pacifist could no longer lead the party, resigned a few days later.[131]

Final years[Hitler] appeared free of personal ambition ... wasn't ashamed of his humble start in life ... lived in the country rather than the town ... was a bachelor who liked children and old people ... and was obviously lonely. I wished that I could have gone to Berchtesgaden and stayed with him for a little while. I felt that Christianity in its purest sense might have had a chance with him.

(Lansbury's impressions after meeting Adolf Hitler in April 1937)[139]

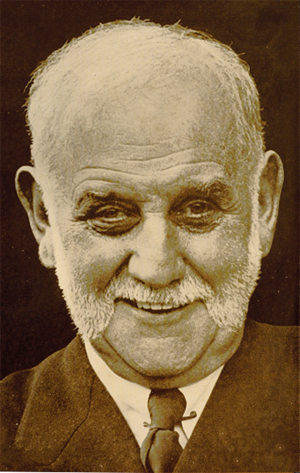

Lansbury was 76 years old when he resigned the Labour leadership; he did not, however, retire from public life. In the general election of November 1935 he kept his seat at Bow and Bromley; Labour, now led by Attlee, improved its parliamentary representation to 154.[138] Lansbury devoted himself entirely to the cause of world peace, a quest that took him, in 1936, to the United States. He addressed large crowds in 27 cities before meeting President Roosevelt in Washington to present his proposals for a world peace conference.[140] In 1937 he toured Europe, visiting leaders in Belgium, France and Scandinavia, and in April secured a private meeting with Hitler. No official report of the discussion was issued, but Lansbury's personal memorandum indicates that Hitler expressed willingness to join in a world conference if Roosevelt would convene it.[141] Later that year Lansbury met Mussolini in Rome; he described the Italian leader as "a mixture of Lloyd George, Stanley Baldwin and Winston Churchill".[142] Lansbury wrote several accounts of his peace journeys, notably My Quest for Peace (1938).[143] His mild and optimistic impressions of the European dictators were widely criticised as naïve and out of touch; some British pacifists were dismayed at Lansbury's meeting with Hitler,[144] while the Daily Worker accused him of diverting attention from the aggressive realities of fascist policies.[142] Lansbury continued to meet European leaders through 1938 and 1939, and was nominated, unsuccessfully, for the 1940 Nobel Peace Prize.[145]

At the funeral of George V, 1936

At the funeral of George V, 1936At home, Lansbury served a second term as Mayor of Poplar, in 1936–37. He argued against direct confrontation with Mosley's Blackshirts during the October 1936 demonstrations known as the Battle of Cable Street.[146] In October 1937 he became president of the Peace Pledge Union,[140] and a year later he welcomed the Munich Agreement as a step towards peace. During this period he worked on behalf of refugees from Nazi Germany, and was chairman of the Polish Refugee Fund which provided relief to displaced Jewish children.[145] On 3 September 1939, after Neville Chamberlain's announcement of war with Germany, Lansbury addressed the House of Commons. Observing that the cause to which he had dedicated his life was going down in ruins, he added: "I hope that out of this terrible calamity will arise a spirit that will compel people to give up the reliance on force."[147]

Early in 1940 Lansbury's health began to fail; although unaware, he was suffering from stomach cancer.[145] In an article published in the socialist magazine Tribune, published on 25 April 1940, he made a final statement of his Christian pacifism: "I hold fast to the truth that this world is big enough for all, that we are all brethren, children of one Father".[148] Lansbury died on 7 May 1940, at the Manor House Hospital in Golders Green. His funeral in St Mary's Church, Bow, was followed by cremation at Ilford Crematorium,[149] before a memorial service in Westminster Abbey.[4] His ashes were scattered at sea, in accordance with the wish expressed in his will: "I desire this because although I love England very dearly ... I am a convinced internationalist".[149]

Tributes and legacyMost historical assessments of Lansbury have tended to stress his character and principles rather than his effectiveness as a party political leader. His biographer Jonathan Schneer writes:

Lansbury was a talented politician, speaker, and organizer. What made him remarkable was the stubbornness with which he clung to his principles... [He] became one of the best-loved and most-respected figures in the labour movement. Lansbury's legacy has been the adamantine insistence among an element within the Labour Party that Britain must stand for moral principles, must set the world a moral example. Concretely, this has meant demanding the total abolition of capitalism and unilateral disarmament, policies that Labour's leaders have usually thought utopian or worse.[150]

The Lansbury Estate, Poplar

The Lansbury Estate, PoplarHistorian A. J. P. Taylor labeled Lansbury as "the most lovable figure in modern politics" and the outstanding figure of the English revolutionary left in the 20th century,[151] while Kenneth O. Morgan, in his biography of a later Labour leader, Michael Foot, regards Lansbury as "an agitator of protest, not a politician of power".[152] Journalists commonly accused Lansbury of sentimentality, and party intellectuals accused him of lacking mental capacity.[153] Nevertheless, his speeches in the House of Commons were often flavoured with historical and literary allusions, and he left behind a considerable body of writing on socialist ideas; Morgan refers to him as a "prophet".[154] Foot, who as a young man met and was influenced by Lansbury, was particularly impressed by the older man's achievements in establishing the Daily Herald, given his complete lack of journalistic training.[155] Nevertheless, Foot felt that Lansbury's pacifism was unrealistic, and believed that Bevin's demolition at the 1935 conference was justified.[156]

There is much agreement among historians and analysts that Lansbury was never self-serving and, guided by his Christian socialist principles, was consistent in his efforts on behalf of the poorest in society.[4] Shepherd believes that "there could have been no better leader for the Labour Party at the collapse of its political fortunes in 1931 than Lansbury, a universally popular choice and a source of inspiration among Labour ranks".[127] In the House of Commons on 8 May 1940, the day following Lansbury's death, Chamberlain said of him: "There were not many hon. Members who felt convinced of the practicability of the methods which he advocated for the preservation of peace, but there was no one who did not realise his intense conviction, which arose out of his deep humanitarianism". Attlee also paid tribute to his former leader: "He hated cruelty, injustice and wrongs, and felt deeply for all who suffered ... [H]e was ever the champion of the weak, and ... to the end of his life he strove for that in which he believed".[157]

After the Second World War, a stained glass window designed by the Belgian artist Eugeen Yoors was placed in the Kingsley Hall community centre in Bow, as a memorial to Lansbury. His memory is further sustained by streets and housing developments named after him, most notably the Lansbury Estate in Poplar, completed in 1951.[153] A further enduring memorial, Attlee suggests, is the extent to which the then-revolutionary social policies that Lansbury began advocating before the turn of the 20th century had become accepted mainstream doctrine little more than a decade after his death.[158]

His name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.[159][160][161]

Personal and family lifeGeorge married Elizabeth Jane (Bessie) Brine on 22 May 1880 in Whitechapel, London. For most of their married life, George and Bessie Lansbury lived in Bow, originally in St Stephen's Road and, from 1916, at 39 Bow Road, a house which, Shepherd records, became "a political haven" for those requiring assistance of any kind.[162] Bessie died in 1933, after 53 years of a marriage that had produced 12 children between 1881 and 1905.[163]

Of the ten who survived to adulthood, Edgar followed his father into local political activism as a Poplar councillor in 1912, serving as the borough's mayor in 1924–25. He was for a time a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). After the death of his first wife Minnie in 1922, Edgar married Moyna Macgill, an actress from Belfast;[164] their daughter Dame Angela Lansbury, born in 1925, became a stage and screen actress.[163]

George Lansbury's youngest daughter Violet (1900–71) was an active CPGB member in the 1920s, who lived and worked in Moscow for many years. She married Clemens Palme Dutt, the brother of the Marxist intellectual Rajani Palme Dutt.[165]

Another daughter, Dorothy (1890–1973), was a women's rights activist and later a campaigner for contraceptive and abortion rights. She married Ernest Thurtle, the Labour MP for Shoreditch, and was herself a member of Shoreditch council, serving as mayor in 1936. She and her husband founded the Workers' Birth Control Group in 1924.[166] Her younger sister Daisy (1892–1971) served as George Lansbury's secretary for 20 years.

In 1913 she helped Sylvia Pankhurst to evade police capture by disguising herself as Pankhurst.[167] She was married to Raymond Postgate, the left-wing writer and historian, who was Lansbury's first biographer and founder of The Good Food Guide.[168] Their son, Oliver Postgate, was a successful writer, animator and producer for children's television.[169]

The Lansbury home at 39 Bow Road was destroyed by bombing during the London Blitz of 1940–41.[170] There is a small memorial stone dedicated to Lansbury in front of the current building, appropriately named George Lansbury House, which itself carries a memorial plaque. There is also a memorial to Lansbury in the nearby Bow Church, where Lansbury was a long-term member of the congregation and churchwarden.

Books by Lansbury• Your Part in Poverty. London: Allen and Unwin. 1918. OCLC 251051169.

• These Things Shall Be. London: Swarthorne Press. 1920. OCLC 1109879.

• What I Saw in Russia. London: L. Parsons. 1920. OCLC 457509320.

• The Miracle of Fleet Street: The Story of the Daily Herald. London: Labour Publishing Company. 1925. OCLC 477300787.

• My Life. London: Constable & Co. 1928. OCLC 2150486.

• My England. London: Selwyn & Blount. 1934. OCLC 2175404.

• Looking Backwards and Forwards. London and Glasgow: Blackie and Son. 1935. OCLC 9072833.

• Labour's Way with the Commonwealth. London: Methuen. 1935. OCLC 574874665.

• The Price of Peace. London: Fellowship of Reconciliation. 1935. OCLC 11084218.

• Why Pacifists Should Be Socialists. London: FACT. 1937. OCLC 826854352.

• My Quest for Peace. London: M. Joseph. 1938. OCLC 4051871.

• This Way to Peace. London: Rich and Cowan. 1940. OCLC 4024194.

See also• List of peace activists

• List of suffragists and suffragettes

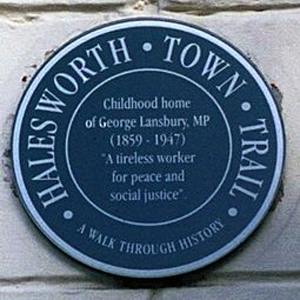

Notes1. Lansbury's biographer Raymond Postgate gives the date and place of birth as 21 February, at the toll-house between Halesworth and Lowestoft, in the county of Suffolk. However, according to his birth certificate, Lansbury was born on 22 February 1859, at a house in Halesworth's "Thoroughfare" or High Street; a plaque provided by a local historical society in 1993 identifies the building as No. 14.[2][3]

2. The English team, managed by Alfred Shaw, was in Australia from November 1884 until the end of March 1885, but the tour record shows no matches played at Brisbane.[14]

3. At that time women, although denied votes in parliamentary elections, had limited rights to vote in municipal elections, although whether they could stand as candidates, or serve if elected, was not legally clear.[22]

4. There being no specific trades union for sawmill workers Lansbury had, in 1889, joined the Gas-workers and General Labourers' Union. He remained a member for the remainder of his life, and for many years attended Labour Party conferences as a union rather than a local party delegate.[32]

5. In 1920 Lansbury published a rationale for his Christian beliefs, under the title These Things Shall Be.[40]

6. In 1907 the school moved to new buildings in Shenfield, Essex. By 1974 it had become an adult training centre; many of the original buildings were demolished and rebuilt in the 1980s.[45]

7. In 1900 the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) had been formed to promote greater working class representation in parliament. In 1906 the LRC became a de facto political party, "the Labour Party", to which socialist bodies (SDF, ILP, trades unions) could affiliate; MPs elected under the LRC banner took the label "Labour". The party did not acquire its modern mass-membership nature until reforms under a new constitution were implemented in 1918.[60]

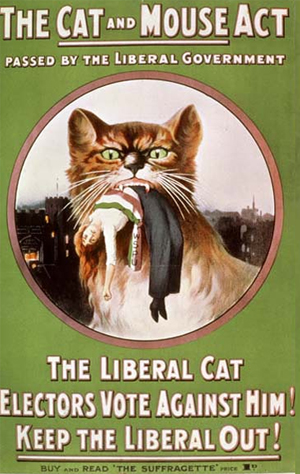

8. The Cat and Mouse Act, officially the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913, allowed for the temporary release of hunger-striking prisoners when they were in danger of death from starvation, and their re-imprisonment when they had sufficiently recovered.[70]

9. Arthur Henderson, who led the parliamentary Labour group between 1914 and 1917, occupied several cabinet posts under Asquith and Lloyd George, and was a member of the latter's small inner war cabinet. Other Labour members with government posts included William Brace and George Roberts.[79]

10. In 1921 the borough of Poplar, with a population of 161,000, has a rateable value of less than £1 million; the product of a penny rate was £3643. By contrast, the rateable value of the wealthy borough of Westminster, with a population of 141,000, was £8 million, and the product of a penny rate was £31,719.[91]

11. Mosley resigned from the government. He later left the Labour Party and formed the New Party, from which developed the British Union of Fascists.[122]

12. The May recommendations were for immediate savings of £120 million (a vast sum at the time), of which £24 million would come from increased taxation and £96 million by expenditure cuts of which the largest proportion would come from unemployment relief. The economist John Maynard Keynes called the May report "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read".[124]

13. Taylor gives the 1931 election result as National Government 521 (Conservatives, National Labour and National Liberals); opposition: Labour 52, Liberal 33, Lloyd George family 4. The Labour total of 52 included 6 ILP members who disaffiliated from the Labour Party in 1932.[121][126]

Citations1. Shepherd 2002, p. 282

2. Postgate, pp. 3–4

3. Shepherd 2002, pp. 5–6

4. Shepherd, John (January 2011). "Lansbury, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 2 February 2013. (subscription required)

5. Postgate, p. 5

6. Blythe, p. 272

7. Shepherd 2002, pp. 8–9

8. Lansbury, pp. 40–43

9. Shepherd 2002, pp. 10–11

10. Postgate, pp. 13–20

11. Postgate, pp. 22–23

12. Postgate, pp. 24–29

13. Shepherd 2002, pp. 13–15

14. "England in Australia : Dec 1884/Mar 1885 (5 Tests)". Cricinfo. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

15. Shepherd 2002, pp. 16–17

16. Postgate, p. 31

17. Shepherd 2002, pp. 19–20

18. Lansbury, p. 75

19. Schneer 1990, pp. 16–17

20. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), p. 67

21. Howe, A.C. (May 2006). "Unwin, (Emma) Jane Catherine Cobden". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 8 February 2013. (subscription required)

22. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), pp. 63–65

23. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), p. 68

24. Hollis, pp. 310–16

25. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), p. 75

26. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), p. 77

27. Schneer ("Politics and Feminism"), pp. 79–80

28. Lansbury article in Labour Leader, 17 May 1912, quoted in Shepherd 2002, p. 26

29. Shepherd 2002, p. 26

30. Shepherd 2002, pp. 32–33

31. Lansbury, p. 2

32. Postgate, p. 41

33. Shepherd 2002, pp. 40–41

34. Shepherd 2002, pp. 44–45

35. Todmorden Advertiser and Hebden Bridge Newsletterreport, 29 November 1895, quoted by Shepherd 2002, p. 47

36. Shepherd 2002, p. 48

37. Shepherd 2002, pp. 78–81

38. Shepherd 2002, p. 77

39. Postgate, p. 55

40. Postgate, p. 60

41. Lansbury, pp. 134–35

42. Shepherd 2002, pp. 54–56

43. Postgate, p. 62

44. Postgate, pp. 67–68

45. Historic England. "Poplar Training School (1453837)". PastScape. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

46. Shepherd 2002, pp. 58–59

47. Shepherd 2002, p. 57

48. Shepherd 2002, pp. 60–61

49. Schneer 1990, pp. 42–43

50. Shepherd 2002, p. 63

51. Postgate, p. 77

52. Schneer 1990, pp. 45–46

53. Postgate, pp. 79–87

54. Postgate, pp. 87–92

55. "Local Government Act 1929". The National Archives. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

56. Shepherd 2002, pp. 83–88

57. Shepherd 2002, p. 89

58. Schneer 1990, p. 95

59. Schneer 1990, p. 93

60. Pelling, Henry (December 1995). "The Emergence of the Labour Party". New Perspective. 1 (2).

61. Shepherd 2002, p. 94

62. Schneer 1990, p. 96

63. Postgate, p. 103

64. Shepherd 2002, pp. 112–13

65. Schneer 1990, p. 104

66. "Grace Roe". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

67. Schneer 1990, p. 107 and 112–17

68. Shepherd 2002, p. 128

69. Shepherd 2002, pp. 131–32

70. Postgate, p. 130

71. Postgate, p. 131

72. Shepherd 2002, pp. 135–37

73. Postgate, pp. 134–38

74. Blythe, pp. 276–77

75. Shepherd 2002, p. 104

76. Shepherd 2002, p. 148

77. Shepherd 2002, p. 158

78. Schneer 1990, p. 136

79. Wrigley, Chris (January 1911). "Henderson, Arthur". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 16 February 2013. (subscription required)

80. Holman. p. 81

81. Boulton, p. 235

82. Schneer 1990, p. 168

83. Postgate, p. 183

84. Postgate, pp. 184–85

85. Shepherd 2002, pp. 183–84

86. Shepherd 2002, pp. 187–88

87. Shepherd 2002, pp. 223–24

88. Postgate, pp. 221–22

89. Postgate, p. 102

90. Shepherd 2002, p. 191

91. Postgate, pp. 216–220

92. Shepherd 2002, p. 194

93. Shepherd 2002, pp. 200–01

94. Shepherd 2002, p. 210

95. Nicolson, pp. 494–98

96. Blythe, pp. 278–79

97. Nicolson, p. 497

98. Postgate, pp. 224–25

99. Martin, Kingsley (1962). The Crown and the Establishment. London: Hutchinson. pp. 53–54. OCLC 1153737.

100. Shepherd, p. 214

101. Shepherd 2002, p. 221

102. Shepherd 2002, p. 222

103. Shepherd 2002, pp. 227 and p. 243

104. Postgate, pp. 236 and 239

105. Postgate, pp. 237–38

106. Postgate, p. 236

107. Shepherd, p. 240

108. Dilks, p. 456

109. Shepherd, p. 238

110. Dilks, p. 576

111. Shepherd 2002, p. 246

112. Shepherd 2002, p. 247

113. Shepherd 2002, p. 250

114. Shepherd 2002, p. 255

115. Shepherd, pp. 256–57

116. Taylor, p. 343

117. Blythe, pp. 281–82

118. Postgate, pp. 251–52

119. Shepherd 2002, p. 253

120. Nicolson, pp. 571–72

121. Taylor, pp. 404–406

122. Skidelsky, Robert (May 2012). "Mosley, Sir Oswald Ernald". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 2 March 2013. (subscription required)

123. Taylor, p. 361

124. Taylor, pp. 362–63

125. Taylor, pp. 366–67

126. Taylor, p. 432

127. Shepherd 2002, p. 286

128. Shepherd 2002, pp. 295–96

129. Blythe, p. 283

130. Postgate, pp. 294–95

131. Vickers, p. 115

132. Vickers, pp. 107–08

133. Vickers, pp. 109–10

134. Blythe, pp. 285–86

135. Heller, Richard (1971). "East Fulham Revisited". Journal of Contemporary History. 6 (4): 172–96.

136. Vickers, p. 112

137. Schneer 1990, p. 172

138. Shepherd 2002, pp. 323–28

139. Blythe, p. 291

140. Schneer 1990, pp. 180–82

141. Shepherd 2002, pp. 338–39

142. Shepherd 2002, p. 341

143. Shepherd, p. 332

144. Prasad, 2005 pp. 177-8

145. Shepherd 2002, pp. 343–45

146. Shepherd 2002, p. 342

147. "Prime minister's announcement". Hansard Online. 3 September 1939. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

148. Article in Tribune, 25 April 1940, quoted in Postgate, p. 324

149. Holman, p. 164

150. Jonathan Schneer, "Lansbury, George" in Fred M. Leventhal, ed., Twentieth-century Britain: an encyclopedia(Garland, 1995) p 438-40.

151. Taylor, p. 191 and p. 270

152. Morgan, p.154

153. Shepherd 2002, pp. 360–63

154. Morgan, p. 482

155. Morgan, p. 132

156. Morgan, p. 77

157. "Tributes to Mr Lansbury and Sir Terence O'Connor". Hansard Online. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

158. Attlee, p. 3

159. "Historic statue of suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett unveiled in Parliament Square". Gov.uk. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

160. Topping, Alexandra (24 April 2018). "First statue of a woman in Parliament Square unveiled". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

161. "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

162. Shepherd 2002, p. 351

163. Shepherd 2002, pp. 347–49

164. Shepherd 2002, p. 307

165. Shepherd 2002, p. 212

166. Brooke, Stephen (January 2008). "Thurtle (née Lansbury), Dorothy". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 1 March 2013.(subscription required)

167. Shepherd 2002, p. 121 and p. 354

168. Pottle, Mark (January 2012). "Postgate, Raymond William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 1 March 2013. (subscription required)

169. Hayward, Anthony. "Postgate, (Richard) Oliver". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online edition. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

170. Blythe, p. 293

Sources• Attlee, Clement (2009). Lansbury of London in Field, Frank: Attlee's Great Contemporaries – The Politics of Character. London: Continuum. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-8264-3224-7.

• Blythe, Ronald (1964). The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. OCLC 10971329.

• Boulton, David (1967). Objection Overruled. London: MacGibbon and Kee. OCLC 956913.

• Dilks, David (1984). Neville Chamberlain, Volume 1: Pioneering and Reform, 1869–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89401-2.

• Hollis, Patricia (1987). Ladies Elect: Women in English Local Government 1865–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822699-3.

• Holman, Bob. Good Old George, The life of George Lansbury, Best-loved leader of the Labour party. Oxford: Lion Books. ISBN 0-7459-1574-4.

• Lansbury, George (1928). My Life. London: Constable and Co. OCLC 2150486.

• Morgan, Kenneth O. (2008). Michael Foot: A Life. London and New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-717827-8.

• Nicolson, Harold (1967). King George V: His Life and Reign. London: Pan Books. OCLC 562582750.

• Postgate, Raymond (1951). George Lansbury. London: Longmans, Green. OCLC 739654.

• Prasad, Devi (2005). War is a crime against humanity : the story of War Resisters' International. London, UK: War Resisters' International. ISBN 0903517205.

• Schneer, Jonathan (1990). George Lansbury: Lives of the Left. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-2170-7.

• Schneer, Jonathan (January 1991). "Politics and Feminism in 'Outcast London': George Lansbury and Jane Cobden's Campaign for the First London County Council". Journal of British Studies. 30 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1086/385973. JSTOR 175737. (subscription required)

• Shepherd, John (2002). George Lansbury: At the Heart of Old Labour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820164-8.

• Taylor, A.J.P. (1970). English History 1914–45. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-021181-0.

• Vickers, Rhiannon (2003). The Labour Party and the World, Volume 1: The Evolution of Labour's Foreign Policy, 1900–51. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6745-6.

External links• UK: Leader of the Opposition, George Lansbury pleads for peace at League of Nations Clip from a Paramount Newsreel, circa 1935

• Catalogue of the Lansbury papers at the Archives Division of the London School of Economics.

• Newspaper clippings about George Lansbury in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

• Movietone footage of George Lansbury speaking about conditions in slums