My England [Excerpt]

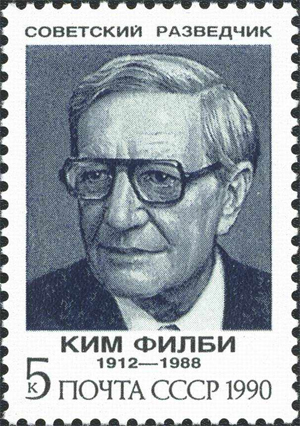

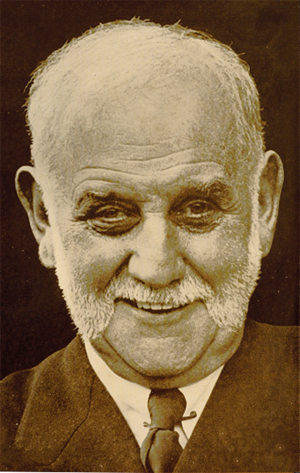

by George Lansbury

1934

Contents:

I: The Future of England

II: The Next Labour Government

III: Religion

IV: Why My England would be a Socialist England

V: Planning

VI: Unemployment and Agriculture

VII: Crime and Punishment

VIII: Health and Hospitals

IX: The Money Octopus

X: The Cabinet and Parliament

XI: The Civil Service and the Experts

XII: Dominions and Colonies

XIII: India

XIV: War, Disarmament and Peace

XV: Fascism

XVI: Ticket-holders and Trade Unionists

XVII: The Joy of Living

XVIII: Conclusion

About this book

Here in this book, George Lansbury, a man of the people, writes from the ripeness of his experience and the depths of his heart.

He outlines many of his hopes and points to ways in which they may be realised; he does not see them as distant visions of Utopias, but as possible and necessary achievements of the near future.

The happiness of his fellow-beings, the safeguarding of their liberty to pursue it, the securing to them of opportunities for complete living, these are the end and aim of all his schemes and dreams. In his own words his “ desire always is to chain down misery and set happiness free.”

Mr. Lansbury does not write for a section of the people alone, but for all, with a sympathy and understanding that is the keynote of his life and work.

Many have wondered why a teetotaller like him should have permitted drinks in the Royal Parks during his regime as Commissioner of Works and why with his ardour for the Christian faith he should be a strong advocate of free thought. In these pages may be found the answer to some of these apparent contradictions.

My England is a personal document; every line of the manuscript was written by the author in his own hand and we have printed it here as it left him.

One: THE FUTURE OF ENGLAND

In this book it is my desire to make as plain as possible what I consider is the main purpose of the Labour Party, and to what extent we differ from all other parties in the State. In no sense is this an official statement of policy, but it is a summary of the propaganda it has been my privilege for many years to carry on as a Socialist speaker. I do not, however, think anything I have written conflicts in any fundamental manner with official policy as set out in the published programme and constitution of the Party.

We are living in the midst of a peaceful revolution. Slowly, but surely, what is known as the “ corporate state ” is being established in this country. Capitalism as understood when Marx wrote Das Kapital, and as it existed when Hyndman, Morris, and the Fabians in turn tried, just as the German and other foreign Socialists did, to set out a programme for Socialism, no longer exists. All the teachings of the Manchester school of political economists which they found it necessary to attack have been scrapped. Big and little business men have given up self-reliance, competition, and individual enterprise, and have become directly or indirectly dependent upon the State for their existence.

Parliament now devotes most of its time devising schemes for the assistance of all kinds of combinations formed to preserve the Capitalist system and return to it the stability which it has lost. Competitive Capitalism is passing away. The help of Governments in all countries is being used to build up huge combinations which eliminate all the waste associated with competition. The Trade Union movement is tending in the same direction. Small unions are joining together and become great combinations. It is certain that in the near future any militant trade unions that there are will, in fact, if they are to be effective, be found to be controlled and organised from two or three centres only. The uniting of all transport workers into one union cannot be much longer delayed. The mining industry is already federated, and it will inevitably be forced by circumstances to adopt a much closer knit form of union. Disputes, whether they are lock-outs or strikes, will be much more serious affairs than ever before. Small strikes are disappearing: the conflicts that appear to-day are always conflicts that at least threaten to become nation-wide struggles, and both sides hesitate before beginning them. I shall not be surprised if in the near future (as has, after all, been nominally done in Italy and Germany) an offer—purely a pretence—of some sort of share in management is offered by combined Capitalist organisations to combined labour. If this happens we shall need to remember that there is no doubt at all that the whole power and object of the Capitalist state will be to preserve for the few the right to extract rent, profit, and interest from the combined labour of the many.

Whatever specious arrangements and agreements are made in the “ corporate state,” what is never ignored is this essential feature of the century-old struggle between both sides. When Fascists say that omelettes cannot be made without breaking eggs, what they really mean is that rent, profit, and interest cannot be made without exploitation.

The polite preparations for the “ corporate state ” are being made under our noses in Great Britain. The descendants of Cobden and Bright no longer denounce State interference. They no longer rest their case for Capitalism on individual freedom to adulterate goods as a legitimate form of competition, or to employ labour on the lowest terms possible. The power of the State is now enlisted for the purpose of organising, combining and rationalising all Capitalist efforts, and by thus doing, securing by regulation of output control of prices, that Capitalism shall still secure its full reward.

The financial interests in the City of London are given an almost over-riding hand in all that concerns the use of money and credit. The power of those who control banking was never so powerful as to-day. No combination of industrialists can work or stop working without the assistance of those who control the issue of credit. Coal, cotton, iron and steel, transport and agriculture, all these most vital industries are being assisted only when the financial aid given is used to preserve rent, profit, and interest.

Few, if any, among the older Socialists ever imagined that State action such as is continually occurring in this country under a Government freely elected by universal suffrage, and on the Continent under dictatorships with make-believe elections, would ever exist. Yet it is so, and the task of men and women in the Labour Movement is to make clear to the electorate that our object is to transform this Capitalist system of exploitation into one of Co-operation. A new England would lead the world in this. It used to be said that German Social Democracy was leading the world Socialists. Certainly Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, and their fellow workers did fine work. They created a perfect machine, very wealthy, and organised (we were told) to the last button. When the War came, this huge organisation went to pieces, and German Social Democracy ceased to function. To a greater or lesser degree, the same thing happened throughout the world. All our international principles were swamped and met the same fate on the battlefields of the world as did the principles of life and conduct given to mankind by Jesus. Socialists rallied to the call of “ our country in danger ” and, almost with unanimity, joined the Christians in the work of slaughter. To-day, Germany, the country of the perfect Socialist machine, is leading mankind away from Socialism and democracy. The German example is the most glaring, but if we are honest we must admit that nearly all Europe, and to some extent even Great Britain, has followed Mussolini. The only change visible in Fascism is that its later developments have been more brutal and bestial than its earlier forms. I do not wish by this to seem to make a self-righteous condemnation even of the Nazis. The blame for their outrages lies partly at least outside Germany. The people of Germany were cruelly used by the victors at Versailles, and after Versailles they were continuously betrayed and cheated by one international conference after another. Within their own land the nation was torn and distracted by all kinds of divisions among Socialists, Communists and Democrats, so that the avenue of peaceful progress was blocked. The old unity on which the early pioneer Socialists relied had completely vanished; the left wing only consisted of powerless, quarrelling and disrupted sects. The result was that the new German manhood which has grown up in the last twenty years was disgusted and despairing, and not unnaturally turned to Hitler, who at least knew what he wanted, and is now putting all its strength into a fight which is simply nationalism. It is the task of British Labour to take up the challenge of Fascism and show the world how a new social order should be built.

I shall endeavour to show how this must be done. We, with our fellow members of the British Commonwealth, possess, by mandate or otherwise, most of the German colonies, and at the end of the War, our people, who had paid a tremendous price in loss of life and suffering, and of material wealth, received in return very huge tracts of territory. We are at this moment the greatest Imperial race in the world. British Labour must make it clear that for us the word Imperialism has no meaning or value. Our Socialism will begin at home. In the England of my ambitions all the natural resources of all these lands will be utilised to the greatest extent. I shall show in this book how this can be done. But I must first say that I see no reason why we should insist on investing our labour power abroad until we have developed the last yard of our own land and its resources. All the world appears to wish to become one huge factory to produce goods to sell abroad. I want to produce for use here and now. We must be prepared to " cultivate our own garden ” if we are to be sure of living.

As to the Dominions, we must realise that all these are loaded with debts, debts incurred owing to the War, and debts undertaken for the purposes of development. These are a heavy burden both on the people of the Dominions and on ourselves. Soon, and very soon, we shall be obliged to establish an international bankruptcy court so that most of these and other national debts may be wiped out. When this happens—and it is very near to us—everybody will realise how essential it is to develop our own resources.

I hope to show how this can be done both at home and in the Dominions, through co-operation between us all. And this, in short, is the object of this book.

This book would have been written in 1931, had I not been elected leader of the Labour Party. I owed my election as leader to no other reason than the fact that I was the only Labour Cabinet Minister who survived the Labour defeat of October, 1931. The two years and two months during which I served as leader before my accident were the busiest and most hard-working in my lifetime. While it was sitting, the House of Commons occupied my time, day and night. At week-ends, propaganda from one end of Britain to the other occupied my days of rest. The appeals from local Labour Parties were innumerable. All this put out of my mind the thoughts which had previously induced me to try my hand again at writing a book.

This work in and out of Parliament was, if very tiring, most enjoyable. Meeting men and women in all parts of the country who are engaged in the task of converting our people to Socialism, made me understand why our Party has been able to recover all the ground we lost in 1931 and to make certain victory for our cause in the near future. Such meetings also compelled me to realise the magnificent, selfless work carried on by relatively poor men and women on behalf of Socialism, and forced me to give all the time possible to assist and encourage them in their glorious task. While I was doing this I had not time for reflection and writing.

After twenty-six months of this kind of work I met with an accident at Gainsborough on December 9th, 1933, an accident which has kept me in hospital for over six months.

The accident was indeed a severe one, but the love and friendship which has been shown me by people of all classes enabled me to bear the tiresomeness of lying still. It has also made it possible for me to write many articles and messages for the Labour Movement, and above all, it has given me the opportunity to write this book. Readers will understand I am not what is styled an intellectual or literary person, but what I write, even if it is not written with literary elegance is, I hope, clear and direct.

I love England and especially dear, ugly East London, more than I can say. As the years pass, my love has grown stronger. I think of this island as a jewel set in the sea. People may chant hymns of hate about our climate, but where on God’s earth is there a land of hedgerows and lanes which every spring-time resound with a chorus of song from innumerable birds, and bursts into a perfect profligacy of flowers and shrubs, trees and bushes, which gladden the sight of all who are privileged to see them. I want my England also to be a land where freedom of body, soul and spirit is as widespread as natural beauty is in the spring-time. Yes, I want our people to join me in striving to bring love into all our lives, because once we love each other, all other things will be added unto us.

I have many thousands of acquaintances belonging to all sorts and conditions of men, but relatively few personal friends outside my own family. I have missed all that side of life associated with clubs and social institutions, not because I am an unsocial Socialist, but simply because it is not possible to enjoy these things and at the same time carry on propaganda.

This kind of life has taught me that though it is true we must get a majority for Socialism before we can hope to see the democratic Socialist State established, it is also true that multitudes of people do understand the foulness of the present system of competitive strife for security and food. They are willing to try almost any scheme of reform or revolution that appears to promise freedom from that strife. It is this hasty judgment that makes Fascism so attractive, not only to young people, but to many middle-aged and old persons as well. My object in all my propaganda is to make such people realise that it is their individual task to reform or revolutionise society, and that democratic action is impossible without them. The mere handing oneself over to any appointed or self-appointed dictator is useless. Even if he could be possessed of all the virtues, the course of nature makes it sure that he will disappear as certainly and as suddenly as he arises.

The Socialist Movement grew out of the first working-class efforts to improve their own conditions. But Robert Owen, the Chartists, the Christian Socialists like Charles Kingsley and Tom Hughes, insisted on altering the struggle for increased wages into a larger struggle. They knew and declared that the new life which machinery was introducing would in the end crush the workers, making them just pieces of machinery; but nobody, one hundred years ago, really understood the fact that the development of the machine age would reduce and continue to reduce the number of workers in productive industry and enormously increase unemployment and casual labour.

But, knowing what they did, they assisted to organise and legalise the unions, and to some extent secured freedom of combination; but they never expected salvation from trade union effort alone.

After them, and in the days of my connection with the Labour and Socialist movement, men like William Morris and H. M. Hyndman, Cunninghame Graham, Herbert Burrowes and many others gave time and money to the movement for the same object, and made a political Socialist movement possible. Not all these pioneers were working class. The unemployed during the years from 1904 to 1914 owe a deep debt of gratitude to Joseph Fels for the many thousands of pounds he spent on the Vacant Land Cultivation Society. Muriel, Counttess De La Warr, with her friends, gave many thousands of pounds before and during the War to keep the Daily Herald and Weekly Herald going, and when the War ended, she was the friend who put on one side over £100,000 to start the new Daily Herald in March, 1919. I recall these facts because one thing that must be remembered is that although the Socialist Movement is a working-class movement which is organised for the purpose of abolishing the wage system and all class antagonism, and can only be successful through the action of the masses themselves, we need to receive, and indeed now receive, enormous help from men and women of all classes. There would have been no Socialist Movement without the aid of people who were not working class.

There is, however, always a danger that movements of any kind may appear to prosper by such help and then fade away when such help for any reason ceases to be available. Three great working-class movements have stood the test of time in Britain: each has received much support from outside sources, but all three in the main have relied and continue to rely on the pence of working men and women. The Co-operative, Trade Union and Friendly Society organisations depend on the masses for existence and support. The Labour Party, pledged to Socialism, is in a different position, and has within its ranks people of all classes, and in my opinion, is stronger because of this. There is another factor which tends to break down, at least to some extent, the barriers between classes. It is the spread of education, not only in the schools and universities, but the continuous growth of purely Socialist education through the classes and lectures organised by the National Council of Labour Colleges, and the less definitely Socialist Workers Educational Association. Many Labour men in the House of Commons owe their standing and position in the Labour Movement almost entirely to education received at Ruskin College or the Labour Colleges. What is more is the fact that working people have discovered the need and value of education and are willing to sacrifice time and energy to acquire knowledge and understanding.

I am anxious also to break down the veiled antagonism between the “intellectuals” and the “purely working class” speakers and writers. There is no reason for disagreement if both sides meet each other as equals and not in a spirit of superiority or self-conscious inferiority. I feel very very keenly on this subject. All my life I have felt a kind of inferiority complex when meeting educated people or even those people who had become leaders. Few people brought up as I was can possess such a good conceit of themselves as some agitators, organisers, speakers and writers claim for themselves. Nowadays I do not take at their own valuation many of the people I come in contact with, though I still find myself sometimes yielding to old habit and doing so.

I shall endeavour to show how all our Labour organisations may be planned so as to escape the snares of separate craft greed, and of corruption, and especially how all of us, called to positions of trust, may fix our minds on the tasks entrusted to us and be willing, whenever necessary, to stand aside and make way for a better or more useful person.

I shall also write about religion. I am not at all a representative Christian: many of my views would be considered heterodox by some bishops and others. I do, however, agree with Tolstoy and others who believed that the coming of Jesus was for the purpose of saving mankind from man-made evil; that all His teaching may be summed up in His great declaration, “Love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul, with all thy strength, and thy neighbour as thyself; this do and thou shalt live.” I do not think I am a Pecksniffian Pharisee, thanking God I am not as other men. My life is like that of most men, full of mistakes, but also full of downright striving after the right. Like everyone else, it is quite natural that inconsistency is my badge. It is that of all men. I believe most people would like to live more peacefully and live according to the Golden Rule, but we are all full of fear. Yet why should we fear a change, however drastic a change it may be? Can anyone out of Bedlam create a more wicked and stupid way of life than ours? God, Nature, call the driving force in life what you will, gives man a reward full measure, in return for labour on land, in mine and mill, and man, dominated by private greed and ambition, strives by might and main to turn this abundance into scarcity. Acres of wheat, cotton, rubber, are ploughed in. Millions of bushels of corn are burned. Oxen, sheep, poultry, eggs, butter, cheese, are either allowed to rot or are destroyed or not produced. A year passes, and Nature or God takes a hand and true shortage appears. Then there is an outcry for water because of the drought. In both cases the poor suffer. In both cases profits are lost. In a world of sane men abundance would be saved for times of need, but first all needs would be supplied. Remember, the tragedy in both cases lies in the fact that millions suffer and die of penury and want because of our failure to be able intelligently to use the good gifts of God.

Two: THE NEXT LABOUR GOVERNMENT

WHAT should the next Labour Government do? This is one of the questions I raised in the previous chapter. I will try and answer it here.

We should, as a Government, have to remember what the Labour Party is. It is an avowed definite Socialist organisation, existing for the purpose of educating ourselves and our fellow citizens on the economic solution of national and world problems. The Government, therefore, will have to apply that solution. The Party must not mislead either itself or others as to its ultimate goal. However long and tedious the road may be, we march breast forward to the Socialist State, and do so because we are convinced that civilisation, 'such as it is, cannot save itself by any other means. The easier path of compromise might suit the worn-out and aged in mind and body, and may commend itself to the new Government. This would be disaster. Those who remain young and loyal in thought and action can do no other than keep their hearts and minds fixed on the star of hope which is co-operation. “ Each for all and all for each ” is our motto. When we say “all” we mean all that the word implies. We must annihilate all distinctions.

I do not mean by this that we want to introduce uniformity. We do not want to make every man and woman like his neighbour, wearing the same clothes, living in the same house, and thinking the same thoughts. This, which is the product of machine Capitalism, is abhorrent to us. What we want to abolish is not distinction, but class distinction. We intend to put an end to a society where the possession of a particular accent, or a particular kind of fine clothes enables a man to be accepted as superior to his fellows.

The most immediate piece of work the Government would have to do is to restore confidence in the power of democracy to work. Throughout the world, Parliaments, including the British Parliament, Mother of these institutions, are badly discredited, and the ugly, brutal, soul-destroying force of dictatorship reigns supreme in many lands. Mussolini, Hitler, and Pilsudski have all been accepted. They were victorious because those who preceded them failed to deal effectively with the perils which beset society.

We may, as we do, most sincerely dislike Fascism. We may point to its destruction of freedom and imposition of Capitalism in a new and more despotic form in the corporate state. But all the same, after our denunciations, we must realise that for the time being all this is accepted. It is accepted because it is a doctrine of action, it is itself action, even though its action is of a sort that is hateful to many millions.

In Britain, all the talk against Parliament is based on its inaction—its delays and its tedious and obstructive old customs. Their effect, of course, is made worse by the obstructive power of the House of Lords and the influence of the Civil Service in favour of inertia. The Party will be under no delusions about any of these matters. The next Government will make some quick changes. Parliament is some seven hundred years old and has lived through many changes in its constitution and proceedings. Its rules and Standing Orders are not sacrosanct, neither are its methods of conducting business. When Speaker Brand, on his own initiative, stopped the interminable flood of talk on the Coercion Bill, he in fact revolutionised House of Commons procedure. His action was accepted and later on, great power was, and still is, vested in the Chair to enable business to be done. Again, in this century it became necessary to introduce the “guillotine’'—a device whereby a controversial Bill is compulsorily disposed of in a fixed number of days. “Voting Supply” is now largely a farce. Scores and hundreds of millions go through without a vote. Not the Insurance Bills, not the Lloyd George Budgets, nor the Reform of the House of Lords, nor the Home Rule Bills could have been got through without these drastic changes in procedure. It is not likely that we shall be able to carry through a complete economic reconstruction without greatly improving the parliamentary machine once more. Constitutional lawyers will remember the precedent of 1911, when the Liberal-Labour-Irish majority carried through the most drastic changes in order to remove hindrances on the quick working of the democratic will. It cut away altogether the Lords’ vote on Finance, and gave power to the House of Commons to legislate after three sessions on its own authority on any subject whatever.

Labour, when it comes into power, will have to modernise parliamentary procedure, give more scope to members, and shorten discussion. Let everyone keep in mind the fact that no one in the Labour Party has advocated the abolition of Parliament. So far from this, we have at all times had discussions, largely on the initiative of Fred Jowett, on how we could make it a more effective workshop.

There must always be full and free discussion. And when that discussion is over, the work must he done. We may remind the Liberals who cry aloud for Parliamentary freedom that most, if not all, restrictions on debates were brought in and carried by Liberal majorities. As any professor will tell you, all our liberties are bounded by the liberties of each other. All who believe in democracy must also believe in majority rule. That is the essence of democracy.

I have no fear of the Royal Family. They have shown their willingness to accept the nation’s will too often to allow of any doubt on that score. Two Labour Governments have come and gone. What stigma of failure attaches to them is not due to the Crown, but to the wretched minority conditions under which they worked. As for the House of Lords, there is a greater possibility here. Suggestions have been made that circumstances might make it necessary to deal with their lordships shortly and sharply. There might be a financial conspiracy by the banks, for example, aided by connivance from certain Treasury officials, to break the Government by financial means. This might show a need for drastic action to prevent the Upper House enforcing delay. I do not know and cannot prophesy. It is, however, certain that if the need for this is clearly put and definitely to the nation, it is not from the Crown that opposition will come.

The main point that must be pressed home is that there must be no ambiguity about our intentions and no hesitancy in our determination to use all constitutional means to attain our ends. Fascists and Communists are united in saying that Parliament, which has completed many political revolutions, cannot accomplish a social and economic one. It is our proud privilege to prove they are wrong. The present Government has shown us the way and I shall in future chapters show how we shall adapt their methods for our ends. But, first and last, we must be sure of what we desire to do and sure of our courage and grit to carry it through.

The new England for which I am working will, of course, be a Socialist England. And this means that we shall only arrive there by a certain way. Other quicker ways, such as alliances with the Liberals, or a snap election for a “Doctor’s Mandate” such as Mr. MacDonald won, may appear to be more attractive, but they are not quicker in the end. If we are going to carry through Socialism we shall pass through some difficult quarters of an hour. This means that we shall have to rely on the loyalty of the workers of this country. And there is only one way of securing that loyalty. It is by telling the workers right from the beginning what we propose to do. For that reason I am convinced that we should fight elections on a straightforward programme of Socialism, without any make-believe. I do not think that we can safely or sensibly attempt to carry through Socialism except after an election which has been fought on this question and has resulted in a majority. Otherwise we should not take office again. That is the lesson of the two MacDonald Governments.

Given this majority then, we shall have to take forthwith steps that will lead us straight to Socialism with no going back. Some of these steps will necessarily be in the nature of relief. We shall have to come to the assistance of the unemployed. We are pledged to raise the school age and give parents’ allowances. I hope we shall do that. In the late Government it is mere truth to say that owing to our position as a minority Government, this question was really shelved. It was not the religious difficulty which alone wrecked our Bill. It was the question of allowances as well. Many, in and out of the Government, were bitterly opposed to the miserable scheme of allowances which that Bill actually carried. One of the first acts of a Socialist Government in power would be to enact that these grants would be paid from national funds and the school age would be raised to sixteen or even higher. With this would come a complete reconstruction of our educational system.

Most of our schools were built in the late ’seventies under the Education Acts. Some are earlier. Some are modern and fairly satisfactory. The last should be left. But in the preparations for a new England one of the most important things will be to pull down about two-thirds of the existing schools. Some of them are so unfit for their purpose as to be material for the Inspector of Nuisances. They are dark, heavy buildings, with narrow windows which look like imitation Victorian churches. They should be pulled down and their places taken by airy, large-windowed buildings which will be more of the bungalow than the church-and-prison type. Incidentally, until our economic life is reconstructed, and possibly for always, the schools would automatically supply one good, well-cooked meal in the middle of the day for every child. Each school would also have a glass of warm or cold milk for every young child on arrival. And a glass of chocolate, cocoa or coffee for the elder children.

However, the main change in education will not be only a matter of feeding and school buildings. The main change must be in the curriculum and size of classes. We must scrap most of the current ideas of education. It is entirely imbecile to suppose that a child’s or a young person’s mind can possibly be developed by herding it together with forty or fifty others and treating all the lot as if their capacities were equal. Healthy minds mean developed minds, not crammed intellects as chickens are crammed to fatten them. We ought to employ thousands more teachers, and also revolutionise their training.

I do not want our children to become half- trained teachers or professors. The variety of our needs is so great—from sewer men to milkmen and scientists to musicians. All the arts and crafts are open, and all of them need training. When we raise the school age it will be in order not to provide book learning only, but to develop character and brain power in each child.

The next palliative action that would have to be taken would be the wide extension of pensions. Here again it is obvious that only a Socialist Government with a majority can hope to secure anything. It would be a silly mistake, and would show we have learned nothing, if we were again to take office without a majority and hope to pass any real pension scheme. I mean by this a scheme which would not only remove the old, but also all those who were not able-bodied out of the labour market. I do not mean that the disabled should be prevented from working. I do mean that their places in industry should be taken by the able- bodied. What the disabled chose to work at in the way of handicrafts could not, I am fairly sure, disturb the market at all seriously. If it did, the matter might have to be reconsidered, but the objection seems to me fantastic.

Are we not mad to allow ourselves to be forced to put children and cripples on the labour market and to exclude the able-bodied? In this matter my motto is “able-bodied first.” We can heal the sick in mind and body and bring them in later.

The new Government would immediately alter the old age pension arrangements. It would bring down the qualifying age to sixty years. It would also raise the figure so that a man could live on it. I do not know how far the Government would be able to go here. There is always a possibility that we might be faced with an actual shortage of labour as in Russia. It is not at all certain that we should have too many workers if we raised the school age and removed disabled persons from the labour market, and if we decided, as we should, that all pensioners of every sort and kind with pensions of, say, £200 a year and upwards, should also leave the labour market. Let us make up our minds to maintain all disabled and partially disabled people and also make full and ample provision for men and women squeezed out of the ranks of labour, and especially take care of single women—spinsters as they are described—whose tragic lonely plight is scarcely recognised. A pension scheme must cover these and everyone else in a similar evil plight. Our nation is wealthy enough to make this universal provision for all in need.

You must remember that a Socialist Government, backed by a majority, would find an immense amount of work waiting to be done. Hours ought to be reduced to thirty-six a week, and there would be enough and more than enough useful work for all able-bodied. Shaw once said “Pull down London.” Even if we are not so drastic, we could at least go through the country and either remodel the “cottage homes” or improve them off the face of the earth. As to towns, there is in all of them oceans of work crying out to be done.

I often think of the Black Country, the industrial parts of Stafford, Warwick and Worcester. Nowhere in the world where I have visited is there such a spectacle of man-made desolation. The Durham, Welsh, and Scottish coalfields are bad, but for sheer man-made spoiling of nature and for downright ugliness, the like of the broad stretch of countryside through which the L.M.S. and Great Western railways pass from Birmingham to beyond Wolverhampton cannot be seen anywhere. The local authorities do their best, but the only thing their efforts do is to call attention to what remains to be done. Huge tracts of land and houses have simply sunk into the earth because of subsidence. This has happened throughout industrial Britain, and not only in the mining districts. Think, too, of the mountainous slag heaps and “ tips,” often smelling and smoking, piled up as monuments to the Capitalist society which, out of such ugliness, has piled up for itself unearned wealth. Here is work which will employ thousands, turning these barren wastes into parks, forestry and agricultural land.

Then there is the land to be saved, and rescued from further flooding. The great Lincolnshire Wash would long ago have been brought into use if we had been Dutchmen. If the Zuyder Zee can be beaten and millions of acres added to Holland, we could do a similar job in Lincolnshire and other parts of our coastline.

Agriculture needs more and more attention and will employ many more people. The coal, iron, steel, cotton, woollen, and transport industries all cry aloud for reconstruction, and this we should do. I cannot conceive that there should be any real unemployment. If there were, through any unforeseen hitch, the unemployed would, of course, have to be maintained by full maintenance grants.

A Socialist Government will reorganise, replan social and industrial life on a basis of true cooperation between inventor and scientists and workers. None of these would be enemies of the other. The object of all endeavours will be social and the end the betterment of all. More food and all other necessaries of life will be available for the masses, and as production increased, a bigger and even bigger leisure time and less labour.

The task before us is very simple. Profit making requires a difficult complex system of working because each set of Capitalists strives to outdo the other. Socialism means exactly the reverse. So the greater the production of goods the more leisure and pleasure for all. My Socialist England will show the world how to use the good gifts of God and Nature, and will forever banish the fear and dread of man-made poverty from our lives. This is no easy task or twenty-four-hour revolution. It may take months and years: all will depend on the determination and driving power of the members of the first Labour Government which will have possessed power. The job to be tackled is one for men of courage and conviction—those who see their goal and the road to it.