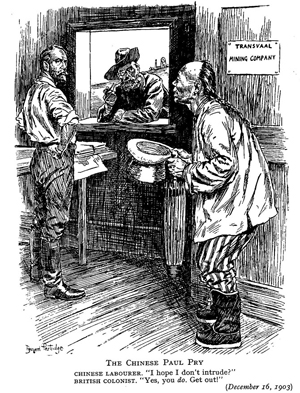

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Part 1 of 2

Guy Burgess

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/22/20

Guy Burgess

Guy Burgess: diplomat and spy

Born: 16 April 1911, Devonport, Devon, England

Died: 30 August 1963 (aged 52), Moscow, Soviet Union

Nationality: British

Other names: Codenames "Mädchen", "Hicks"

Known for: Member of "Cambridge Five" spy ring; defected to Soviet Union 1951

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British diplomat and Soviet agent, a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His defection in 1951 to the Soviet Union, with his fellow spy Donald Maclean, led to a serious breach in Anglo-United States intelligence co-operation, and caused long-lasting disruption and demoralisation in Britain's foreign and diplomatic services.

Born into a wealthy middle-class family, Burgess was educated at Eton College, the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth and Trinity College, Cambridge. An assiduous networker, he embraced left-wing politics at Cambridge and joined the British Communist Party. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of the future double-agent Kim Philby. After leaving Cambridge, Burgess worked for the BBC as a producer, briefly interrupted by a short period as a full-time MI6 intelligence officer, before joining the Foreign Office in 1944.

At the Foreign Office, Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, the deputy to Ernest Bevin, the Foreign Secretary. This post gave Burgess access to secret information on all aspects of Britain's foreign policy during the critical post-1945 period, and it is estimated that he passed thousands of documents to his Soviet controllers. In 1950 he was appointed second secretary to the British Embassy in Washington, a post from which he was sent home after repeated misbehaviour. Although not at this stage under suspicion, Burgess nevertheless accompanied Maclean when the latter, on the point of being unmasked, fled to Moscow in May 1951.

Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations. He never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported on a lonely and empty existence. He remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason. He was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963. Experts have found it difficult to assess the extent of damage caused by Burgess's espionage activities, but consider that the disruption in Anglo-American relations caused by his defection was perhaps of greater value to the Soviets than any information he provided. Burgess's life has frequently been fictionalised, and dramatised in productions for screen and stage.

Life

Family background

The Burgess family's English roots can be traced to the arrival in Britain in 1592 of Abraham de Bourgeous de Chantilly, a refugee from the Huguenot religious persecutions in France. The family settled in Kent, and became prosperous, mainly as bankers.[1] Later generations created a military tradition; Guy Burgess's grandfather, Henry Miles Burgess, was an officer in the Royal Artillery whose main service was in the Middle East. His youngest son, Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess, was born in Aden in 1881,[1] the third forename being a nod to his Huguenot ancestry.[2] Malcolm had a generally unremarkable career in the Royal Navy,[3] eventually reaching the rank of Commander.[2] In 1907 he married Evelyn Gillman, the daughter of a wealthy Portsmouth banker. The couple settled in the naval town of Devonport where, on 16 April 1911, their elder son was born, christened Guy Francis de Moncy. A second son, Nigel, was born two years later.[3]

Childhood and schooling

Eton College, which Burgess attended in 1924 and between 1927 and 1930

The Gillman wealth ensured a comfortable home for the young family.[4] Guy's earliest schooling was probably with a governess until, aged nine, he began as a boarder at Lockers Park, an exclusive preparatory school near Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire. He did well there; his grades were consistently good and he played for the school's association football team.[5] Having completed the Lockers curriculum a year early, he was too young to proceed immediately, as intended, to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth.[n 1] Instead, from January 1924 he spent a year at Eton College, Britain's most prestigious public school.[8]

Following Malcolm Burgess's retirement from the navy, the family moved to West Meon in Hampshire. Here, on 15 September 1924, Malcolm died suddenly of a heart attack.[9] Despite this traumatic event, Guy's education proceeded as planned, and in January 1925 he began at Dartmouth.[10][n 2] Here he encountered strict discipline and insistence on order and conformity, enforced by frequent use of corporal punishment even for minor infringements.[12] In this environment, Burgess thrived both academically and at sports.[13] He was marked by the college authorities as "excellent officer material",[14] but an eye test in 1927 exposed a deficiency that precluded a career in the navy's executive branch. Burgess had no interest in the available alternatives – the engineering or paymaster branches – and in July 1927 he left Dartmouth and returned to Eton.[15][n 3]

Burgess's second period at Eton, between 1927 and 1930, was largely rewarding and successful, both academically and socially. Although he failed to be elected to the elite society known as "Pop",[16] he began to develop a network of contacts that would prove useful in later life.[17] At Eton, sexual relationships between boys were common,[18] and although Burgess would claim that his homosexuality began at Eton, his contemporaries could recall little evidence of this.[19] Generally, Burgess was remembered as amusingly flamboyant, and something of an oddity with his professed left-wing social and political opinions.[20] In January 1930 he sat for and won a history scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, concluding his school career with further prizes in history and drawing.[21] Throughout his life he retained fond memories of Eton; according to his biographers Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert he "never showed any embarrassment that he had been educated in a citadel of educational privilege".[22]

Cambridge

Undergraduate

Burgess arrived in Cambridge in October 1930, and quickly involved himself in many aspects of student life. He was not universally liked; one contemporary described him as "a conceited unreliable shit", although others found him amusing and good company.[23] After a term, he was elected to the Trinity Historical Society whose membership was formed from the brightest of Trinity College undergraduates and postgraduates. Here he encountered Kim Philby, and also Jim Lees, a former miner studying under a trade union scholarship, whose working-class perspective Burgess found stimulating.[24] In June 1931 Burgess designed the stage sets for a student production of Bernard Shaw's play Captain Brassbound's Conversion, with Michael Redgrave in the leading role.[25][26] Redgrave considered Burgess "one of the bright stars of the university scene, with a reputation for being able to turn to anything".[27]

Great Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

Burgess by this time made no attempt to conceal his homosexuality. In 1931 he met Anthony Blunt, four years his senior and a Trinity postgraduate. The two shared artistic interests and became friends, possibly lovers.[28] Blunt was a member of the intellectual society known as the "Apostles", to which in 1932 he secured Burgess's election.[29] This gave Burgess a greatly extended range of networking opportunities;[30] membership of the Apostles was lifelong, so at the regular meetings he met many of the leading intellectuals of the day, such as G. M. Trevelyan, the University's Regius Professor of History, the writer E. M. Forster, and the economist John Maynard Keynes.[31]

In the early 1930s the general political climate was volatile and threatening. In Britain, the financial crisis of 1931 pointed to the failure of capitalism, while in Germany the rise of Nazism was a source of increasing disquiet.[32] Such events radicalised opinion in Cambridge and elsewhere;[33] according to Burgess's fellow Trinity student James Klugmann, "Life seemed to demonstrate the total bankruptcy of the capitalist system and shouted aloud for some sort of quick, rational, simple alternative".[34] Burgess's interest in Marxism, initiated by friends such as Lees, deepened after he heard the historian Maurice Dobb, a fellow of Pembroke College, address the Trinity Historical Society on the issue of "Communism: a Political and Historical Theory". Another influence was a fellow student, David Guest, a leading light in the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS), within which he formed the university's first active communist cell. Under Guest's influence, Burgess began studying the works of Marx and Lenin.[35]

Amid these political distractions, in 1932 Burgess obtained first-class honours in Part I of the history Tripos, and was expected to graduate with similar honours in Part II the following year. But although he worked hard, political activity distracted him and by the time of his final examinations in 1933 he was unprepared. During his examinations he fell ill and was unable to complete his papers; this may have been the consequence of belated cramming, or of taking amphetamines.[36] The examiners awarded him an aegrotat, an unclassified degree awarded to students considered worthy of honours but prevented through illness from completing their examinations.[37][n 4]

Postgraduate

Cambridge War Memorial, focus of demonstrations in November 1933

Despite his disappointing degree result, Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1933 as a postgraduate student and teaching assistant. His chosen research area was "Bourgeois Revolution in Seventeenth-Century England", but much of his time was devoted to political activism. That winter he formally joined the British Communist Party and became a member of its cell within CUSS.[41] On 11 November 1933 he joined a mass demonstration against the perceived militarism of the city's Armistice Day celebrations. The protestors' objective, laying a wreath bearing a pacifist message at the Cambridge War Memorial, was achieved, despite attacks and counter-demonstrations which included what the historian Martin Garrett describes as "a hail of pro-war eggs and tomatoes".[42][43] Alongside Burgess was Donald Maclean, a languages student from Trinity Hall and an active CUSS member.[44] In February 1934 Burgess, Maclean and fellow members of CUSS welcomed the Tyneside and Tees-side contingents of that month's National Hunger March, as they passed through Cambridge on their way to London.[45][44][46]

When not occupied in Cambridge, Burgess made frequent visits to Oxford, to confer with kindred spirits there; according to an Oxford student's later reminiscences, at that time "it was impossible to be in the intellectual swim ... without coming across Guy Burgess".[47] Among those he befriended was Goronwy Rees, a young Fellow of All Souls College.[48] Rees had planned to visit the Soviet Union with a fellow don in the 1934 summer vacation, but was unable to go; Burgess took his place. During the carefully escorted trip, in June–July 1934, Burgess met some notable figures, including possibly Nikolai Bukharin, editor of Izvestia and former secretary of the Comintern. On his return, Burgess had little to report, beyond commenting on the "appalling" housing conditions while praising the country's lack of unemployment.[49]

Recruitment as Soviet agent

When Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1934, his prospects of a college fellowship and an academic career were fast receding. He had abandoned his research after discovering that the same ground was covered in a new book by Basil Willey. He began an alternative study of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but his time was largely preoccupied with politics.[50][51]

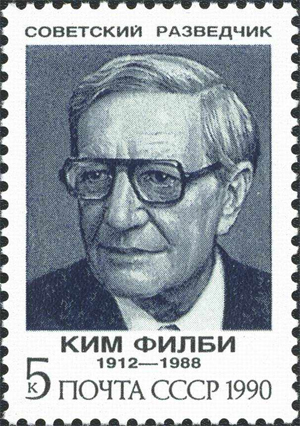

Kim Philby, as depicted on a Soviet Union stamp

Early in 1934 Arnold Deutsch, a longstanding Soviet secret agent, arrived in London under the cover of a research appointment at University College, London. Known as "Otto", his brief was to recruit the brightest students from Britain's top universities, who might in future occupy leading positions in British institutions.[52][53] In June 1934 he recruited Philby, who had come to the Soviets' notice earlier that year in Vienna where he had been involved in demonstrations against the Dollfuss government.[54] Philby recommended several of his Cambridge associates to Deutsch, including Maclean, by this time working in the Foreign Office.[55] He also recommended Burgess, although with some reservations on account of the latter's erratic personality.[56] Deutsch considered Burgess worth the risk, "an extremely well-educated fellow, with valuable social connections, and the inclinations of an adventurer".[57] Burgess was given the codename "Mädchen", meaning "Girl", later changed to "Hicks".[58] Burgess then persuaded Blunt that he could best fight fascism by working for the Soviets.[59] A few years later another Apostle, John Cairncross, was recruited by Burgess and Blunt, to complete the spy ring often characterised as the "Cambridge Five".[60][61][n 5]

Finally recognising that he had no future career at Cambridge, Burgess left in April 1935.[63] The long-term aim of the Soviet intelligence services[n 6] was for Burgess to penetrate British intelligence,[65] and with this in mind he needed to publicly distance himself from his communist past. Thus he resigned his Communist Party membership and publicly renounced communism, with a gusto that shocked and dismayed his former comrades.[66][67] He then looked for suitable work, applying without success for positions with the Conservative Research Department and Conservative Central Office.[63] He sought a teaching job at Eton, but was rejected when a request for information from his former Cambridge tutor received the reply: "I would very much prefer not to answer your letter".[68]

Late in 1935 Burgess accepted a temporary post as personal assistant to John Macnamara, the recently elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Chelmsford. Macnamara was on the right of his party; he and Burgess joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, which promoted friendship with Nazi Germany. This enabled Burgess to disguise his political past very effectively, while gathering important information about Germany's foreign policy intentions.[69] Within the Fellowship, Burgess would proclaim fascism as "the wave of the future", although in other forums such as the Apostles he was more circumspect.[70] The association with Macnamara involved several trips to Germany; some, by Burgess's own later version of events, of a decidedly dissolute nature – both men were practising homosexuals.[71] These stories, according to the historian Michael Holzman, may have been invented or exaggerated to draw attention away from Burgess's true motives.[72]

In the autumn of 1936 Burgess met the nineteen-year-old Jack Hewit in The Bunch of Grapes, a well-known homosexual bar in The Strand. Hewit, a would-be dancer seeking work in London's musical theatres, would be Burgess's friend, manservant and intermittent lover for the next fourteen years,[73] generally sharing Burgess's various London homes: Chester Square from 1936 to 1941, Bentinck Street from 1941 to 1947, and New Bond Street from 1947 until 1951.[74][75]

BBC and MI6

BBC: first stint

In July 1936, having twice previously applied unsuccessfully for posts at the BBC, Burgess was appointed as an assistant producer in the Corporation's Talks Department.[76] Responsible for selecting and interviewing potential speakers for current affairs and cultural programmes, he drew on his extensive range of personal contacts and rarely met refusal.[77] His relationships at the BBC were volatile; he quarrelled with management about his pay,[78][79] while colleagues were irritated by his opportunism, his capacity for intrigue,[77] and his slovenliness. One colleague, Gorley Putt, remembered him as "a snob and a slob ... It amazed me, much later in life, to learn that he had been irresistibly attractive to most people he met".[80]

Old Broadcasting House, BBC's London HQ from 1932 (photographed in 2007)

Among those Burgess invited to broadcast were Blunt, several times, the well-connected writer-politician Harold Nicolson (a fruitful source of high-level gossip), the poet John Betjeman, and Kim Philby's father, the Arabist and explorer St John Philby.[81] Burgess also sought out Winston Churchill, then a powerful backbench opponent of the government's appeasement policy. On 1 October 1938, during the Munich crisis, Burgess, who had met Churchill socially, went to the latter's home at Chartwell to persuade him to reconsider his decision to withdraw from a projected talks series on Mediterranean countries.[82][83] According to the account provided in Tom Driberg's biography, the conversation ranged over a series of issues, with Burgess urging the statesman to "offer his eloquence" to help resolve the current crisis. The meeting ended with the presentation to Burgess of a signed copy of Churchill's book Arms and the Covenant,[84] but the broadcast did not take place.[85]

Pursuing their main objective, the penetration of the British intelligence agencies, Burgess's controllers asked him to cultivate a friendship with the author David Footman, who they knew was an MI6 officer. Footman introduced Burgess to his superior, Valentine Vivian; as a result, over the following eighteen months Burgess carried out several small assignments for MI6 on an unpaid freelance basis.[86] He was trusted sufficiently to be used as a back channel of communication between the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, and his French counterpart Edouard Daladier, during the period leading to the 1938 Munich summit.[87]

At the BBC, Burgess thought his choices of speaker were being undermined by the BBC's subservience to the government – he attributed Churchill's non-appearance to this – and in November 1938, after another of his speakers was withdrawn at the request of the prime minister's office, he resigned.[88] MI6 was by now convinced of his future utility, and he accepted a job with its new propaganda division, known as Section D.[89] In common with the other members of the Cambridge Five, his entry to British intelligence was achieved without vetting; his social position and personal recommendation were considered sufficient.[90]

Section D

Foreign ministers Molotov (left) and Ribbentrop at the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact

Section D was established by MI6 in March 1938, as a secret organisation charged with investigating how enemies might be attacked other than through military operations.[91] Burgess acted as Section D's representative on the Joint Broadcasting Committee (JBC), a body set up by the Foreign Office to liaise with the BBC over the transmission of anti-Hitler broadcasts to Germany.[92] His contacts with senior government officials enabled him to keep Moscow abreast of current government thinking. He informed them that the British government saw no need for a pact with the Soviets, since they believed Britain alone could defeat the Germans without Russian assistance.[93][94] This information reinforced the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's suspicions of Britain, and may have helped to hasten the Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939.[95]

After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Burgess, with Philby who had been brought into Section D on his recommendation,[96] ran a training course for would-be saboteurs, at Brickendonbury Manor in Hertfordshire. Philby later was sceptical of the value of such training, since neither he nor Burgess had any idea of the tasks these agents would be expected to perform behind the lines in German-occupied Europe.[97] In 1940, Section D was absorbed into the new Special Operations Executive (SOE). Philby was posted to a SOE training school in Beaulieu, and Burgess, who in September had been arrested for drunken driving (the charge was dismissed on payment of costs), found himself at the end of the year out of a job.[98]

BBC: second stint

In mid-January 1941 Burgess rejoined the BBC Talks Department,[99] while continuing to carry out freelance intelligence work, both for MI6[100] and its domestic intelligence counterpart MI5, which he had joined in a supernumerary capacity in 1940.[101] After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the BBC required Burgess to select speakers who would depict Britain's new Soviet ally in a favourable light.[102][103][104] He turned again to Blunt, and to his old Cambridge friend Jim Lees,[105] and in 1942 arranged a broadcast by Ernst Henri, a Soviet agent masquerading as a journalist. No transcript of Henri's talk survives, but listeners remembered it as pure Soviet propaganda.[106] In October 1941 Burgess took charge of the flagship political programme The Week in Westminster, which gave him almost unlimited access to Parliament.[107] Information gleaned from regular wining, lunching and gossiping with MPs was invaluable to the Soviets, regardless of the content of the programmes that resulted.[108] Burgess sought to maintain a political balance; his fellow Etonian Quintin Hogg, a future Conservative Lord Chancellor, was a regular broadcaster,[109] as, from the opposite social and political spectrum, was Hector McNeil, a former journalist who became a Labour MP in 1941 and served as a parliamentary private secretary in the Churchill war ministry.[110]

Burgess had lived in a Chester Square flat since 1935.[111] From Easter 1941 he shared a house with Blunt and others at No. 5 Bentinck Street.[112] Here, Burgess maintained an active social life with his many acquaintances, both regular and casual;[n 7] Goronwy Rees likened the Bentinck Street ambience to that of a French farce: "Bedroom doors opened and shut, strange faces appeared and disappeared down the stairs where they passed some new visitor coming up..."[114] This account was disputed by Blunt, who claimed that such casual comings and goings were contrary to house rules, since they would have disrupted other tenants' sleep.[115]

Burgess's casual work for MI5 and MI6 deflected official suspicion as to his true loyalties,[116] but he lived in constant fear of exposure, particularly as he had revealed the truth to Rees, when trying to recruit the latter in 1937.[117][118] Rees had since renounced communism, and was serving as an officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers.[119] Believing that Rees might expose him and others, Burgess suggested to his handlers that they should kill Rees, or alternatively that he should do the job himself. Nothing came of this proposal.[120][121] Always seeking ways of further penetrating the citadels of power, when in June 1944 Burgess was offered a job in the News Department of the Foreign Office, he accepted it.[122] The BBC reluctantly assented to his release, stating that his departure would be "a serious loss".[123]

Foreign Office

London

As a press officer in the Foreign Office News Department, Burgess's role involved explaining government policy to foreign editors and diplomatic correspondents.[124] His access to secret material enabled him to send Moscow important details of allied policy both before and during the March 1945 Yalta Conference.[125] He passed information relating to the postwar futures of Poland and Germany, and also contingency plans for "Operation Unthinkable", which anticipated a future war with the Soviet Union.[126] His Soviet masters rewarded his efforts with a £250 bonus.[58][n 8] Burgess's working methods were characteristically disorganised, and his tongue was loose; according to his colleague Osbert Lancaster, "[w]hen in his cups he made no bones about working for the Russians".[128]

Burgess had maintained contact with McNeil who, following Labour's victory in the 1945 General Election, became Minister of State at the Foreign Office, effectively Ernest Bevin's deputy. McNeil, a staunch anti-communist unsuspecting of Burgess's true allegiance, admired the latter for his sophistication and intelligence, and in December 1946 secured his services as an additional private secretary.[129] The appointment was in breach of regular Foreign Office procedures, and there were complaints, but McNeil prevailed.[130] Burgess quickly made himself indispensable to McNeil,[131] and in one six-month period transmitted to Moscow the contents of 693 files, a total of over 2,000 photographed pages, for which he received a further cash reward of £200.[132][n 9]

Early in 1948 Burgess was seconded to the Foreign Office's newly created Information Research Department (IRD), set up to counteract Soviet propaganda.[133] The move was not a success; he was indiscreet, and his new colleagues thought him "dirty, drunken and idle".[134] He was quickly sent back to McNeil's office, and in March 1948 accompanied McNeil and Bevin to Brussels for the signing of the Treaty of Brussels, which eventually led to the establishment of the Western European Union and NATO.[135] He remained with McNeil until October 1948, when he was posted to the Foreign Office's Far East Department.[136] Burgess was assigned to the China desk at a point when the Chinese civil war was nearing its climax, a communist victory imminent. There were important differences of view between Britain and the U.S. on future diplomatic relations with the forthcoming communist state.[137] Burgess was a forceful advocate for recognition, and may have influenced Britain's decision to recognise communist China in 1949.[138]

In February 1949, a fracas at a West End Club – possibly the RAC – resulted in a fall downstairs that left Burgess with severe head injuries, following which he was hospitalised for several weeks.[137][139] Recovery was slow; according to Holzman he never functioned well after that.[140] Nicolson noted the decline: "Oh my dear, what a sad, sad thing this constant drinking is! Guy used to have one of the most rapid and active minds I knew".[141] Later in 1949 a holiday in Gibraltar and North Africa became a catalogue of drunkenness, promiscuous sex, and arguments with diplomatic and MI6 staff, exacerbated by the frankly homophobic attitudes towards Burgess by some local officials.[142][143] Back in London, Burgess was reprimanded,[144] but somehow retained the confidence of his superiors, so that his next posting, in July 1950, was to Washington, as second secretary in what Purvis and Hulbert describe as "one of the UK's highest profile embassies, the creme de la creme of diplomatic postings".[145]

Washington

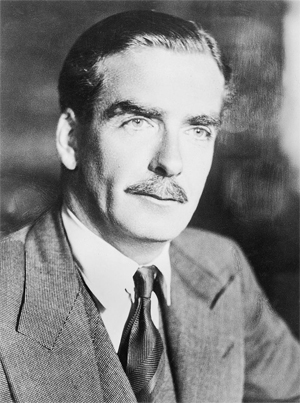

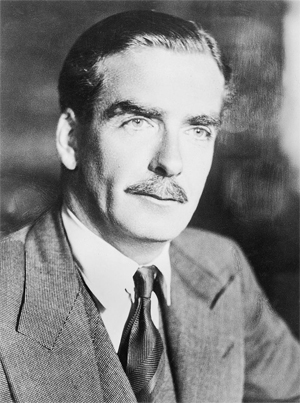

Anthony Eden, Burgess's "guest"

Philby had preceded Burgess to Washington, and was serving there as local head of MI6,[146] following in the path of Maclean who had worked as the embassy's first secretary between 1944 and 1948.[147][n 10] Burgess soon reverted to his erratic and intemperate habits, causing regular embarrassment in British diplomatic circles.[149][150][151] Despite this, he was given work of top secret sensitivity. Among his duties he served on the inter-allied board responsible for the conduct of the Korean War, which gave him access to America's strategic war plans.[149] His frequent behavioural lapses did not prevent his being chosen to act as escort to Anthony Eden, when the future British prime minister visited Washington in November 1950. The episode passed without trouble; the two, both Etonians, got on well, and Burgess received a warm letter of thanks from Eden "for all your kindness".[152]

Increasingly, Burgess was dissatisfied with his job. He considered leaving the diplomatic service altogether, and began sounding out his Eton friend Michael Berry about a journalistic post on The Daily Telegraph.[153] Early in 1951 a series of indiscretions, including three speeding tickets on a single day, made his position at the embassy untenable, and he was ordered by the ambassador, Sir Oliver Franks, to return to London.[154][n 11] Meanwhile, the U.S. Army's Venona counterintelligence project, investigating the identity of a Soviet spy codenamed "Homer" who had been active in Washington a few years earlier, had unearthed strong evidence that pointed to Donald Maclean. Philby and his Soviet spymasters believed that Maclean might crack when confronted by British intelligence, and expose the entire Cambridge ring.[156] Burgess was thus given the task, on reaching London, of organising Maclean's defection to the Soviet Union.[157]

Defection

Departure

Burgess returned to England on 7 May 1951. He and Blunt then contacted Yuri Modin, the Soviet spymaster in charge of the Cambridge ring, who began arrangements with Moscow to receive Maclean.[158][159] Burgess showed little urgency in proceeding with the matter,[160] finding time to pursue his personal affairs and attend an Apostles dinner in Cambridge.[161][162] On 11 May he was summoned to the Foreign Office to answer for his misconduct in Washington and, according to Boyle, was dismissed.[163] Other commentators say he was invited to resign or "retire", and was given time to consider his position.[161][164]

Burgess's diplomatic career was over, although he was not at this stage under any suspicion of treachery. He met with Maclean several times; according to Burgess's 1956 account to Driberg, the question of defection to Moscow was not raised until their third meeting, when Maclean said he was going and requested Burgess's help.[165] Burgess had previously promised Philby that he would not go with Maclean, since a double defection would put Philby's own position in serious jeopardy.[166] Blunt's unpublished memoirs state that it was Moscow's decision to send Burgess with Maclean who, they thought, would be unable to handle the complicated escape arrangements alone.[167] Burgess told Driberg that he had agreed to accompany Maclean because he was leaving the Foreign Office anyway, "and I probably couldn't stick the job at the Daily Telegraph".[165]

SS Falaise, the ship on which Burgess and Maclean fled in May 1951

Meanwhile, the Foreign Office had fixed Monday 28 May as the date for confronting Maclean with their suspicions. Philby notified Burgess who, on Friday 25 May, bought two tickets for a weekend channel cruise on the steamship Falaise.[168] These short cruises docked at the French port of St Malo, where passengers could disembark for a few hours without passport checks.[169] Burgess also hired a saloon car, and that evening drove to Maclean's house at Tatsfield in Surrey, where he introduced himself to Maclean's wife Melinda as "Roger Styles".[n 12] After the three had dined, Burgess and Maclean drove rapidly to Southampton, boarding the Falaise just before its midnight departure – the hired car was left abandoned on the quayside.[168]

The pair's subsequent movements were revealed later. On arrival in St Malo they took a taxi to Rennes, then travelled by rail to Paris and on to Berne in Switzerland. Here, by prior arrangement, they were issued with papers at the Soviet embassy, before travelling to Zurich, where they caught a flight to Prague. Safely behind the Iron Curtain, they were able to proceed smoothly on the final stages of their journey to Moscow.[169]

Aftermath

On Saturday 26 May, Hewit informed a friend that Burgess had not come home the previous night. Since Burgess never went away without telling his mother, his absence caused some anxiety in his circle.[170] Maclean's non-appearance at his desk on the following Monday raised concerns that he might have absconded. Disquiet increased when officials realised that Burgess, too, was missing; the discovery of the abandoned car, hired in Burgess's name, together with Melinda Maclean's revelations about "Roger Styles", confirmed that both had fled.[169] Blunt quickly visited Burgess's flat in New Bond Street and removed incriminating materials.[171] An MI6 search of the flat revealed papers that compromised another member of the Cambridge ring, Cairncross, who was later required to resign from his civil service post.[172]

The news of the double flight alarmed the Americans, following the recent conviction of the atomic spy Klaus Fuchs, and the defection of the physicist Bruno Pontecorvo the previous year.[173][174] Aware that his own position was now precarious, Philby recovered various spying paraphernalia from Burgess's former Washington quarters, and buried them in a nearby wood.[175] Summoned to London in June 1951, he was interrogated for several days by MI6. There were strong suspicions that he was responsible for forewarning Maclean via Burgess, but in the absence of conclusive evidence he faced no action and was permitted to retire quietly from MI6.[176]

In the immediate aftermath the Foreign Office made nothing public.[177] In private circles, many rumours abounded: the pair had been kidnapped by the Russians, or by the Americans, or were replicating the flight of Rudolf Hess to Scotland in 1941 in an unofficial peace mission.[178] The press was suspicious, and the story finally broke in the Daily Express on 7 June.[179] A cautious Foreign Office statement then confirmed that Maclean and Burgess were missing and were being treated as absent without leave.[180] In the House of Commons the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison, said there was no indication that the missing diplomats had taken secret documents with them, nor would he attempt to prejudge the issue of their destination.[181]

On 30 June the Express offered a reward of £1,000 for information on the diplomats' current whereabouts, an amount dwarfed shortly afterwards by the Daily Mail's offer of £10,000.[182] There were numerous false sightings in the months that followed. Some press reports speculated that Burgess and Maclean were being held in Moscow's Lubyanka prison.[182] Harold Nicolson thought the Soviets would "use [Burgess] for a month or so and then quietly shove him into some salt mine".[183] Just before Christmas 1953, Burgess's mother received a letter from her son, postmarked in South London. The letter, full of affection and messages for his friends, revealed nothing of his location or circumstances.[184] In April 1954 a senior MGB officer, Vladmir Petrov, defected in Australia. He brought with him papers indicating that Burgess and Maclean had been Soviet agents since their Cambridge days, that the MGB had masterminded their escape,[185] and that they were alive and well in the Soviet Union.[186]

Guy Burgess

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/22/20

Guy Burgess

Guy Burgess: diplomat and spy

Born: 16 April 1911, Devonport, Devon, England

Died: 30 August 1963 (aged 52), Moscow, Soviet Union

Nationality: British

Other names: Codenames "Mädchen", "Hicks"

Known for: Member of "Cambridge Five" spy ring; defected to Soviet Union 1951

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (16 April 1911 – 30 August 1963) was a British diplomat and Soviet agent, a member of the Cambridge Five spy ring that operated from the mid-1930s to the early years of the Cold War era. His defection in 1951 to the Soviet Union, with his fellow spy Donald Maclean, led to a serious breach in Anglo-United States intelligence co-operation, and caused long-lasting disruption and demoralisation in Britain's foreign and diplomatic services.

Born into a wealthy middle-class family, Burgess was educated at Eton College, the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth and Trinity College, Cambridge. An assiduous networker, he embraced left-wing politics at Cambridge and joined the British Communist Party. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1935, on the recommendation of the future double-agent Kim Philby. After leaving Cambridge, Burgess worked for the BBC as a producer, briefly interrupted by a short period as a full-time MI6 intelligence officer, before joining the Foreign Office in 1944.

At the Foreign Office, Burgess acted as a confidential secretary to Hector McNeil, the deputy to Ernest Bevin, the Foreign Secretary. This post gave Burgess access to secret information on all aspects of Britain's foreign policy during the critical post-1945 period, and it is estimated that he passed thousands of documents to his Soviet controllers. In 1950 he was appointed second secretary to the British Embassy in Washington, a post from which he was sent home after repeated misbehaviour. Although not at this stage under suspicion, Burgess nevertheless accompanied Maclean when the latter, on the point of being unmasked, fled to Moscow in May 1951.

Burgess's whereabouts were unknown in the West until 1956, when he appeared with Maclean at a brief press conference in Moscow, claiming that his motive had been to improve Soviet-West relations. He never left the Soviet Union; he was often visited by friends and journalists from Britain, most of whom reported on a lonely and empty existence. He remained unrepentant to the end of his life, rejecting the notion that his earlier activities represented treason. He was well provided for materially, but as a result of his lifestyle his health deteriorated, and he died in 1963. Experts have found it difficult to assess the extent of damage caused by Burgess's espionage activities, but consider that the disruption in Anglo-American relations caused by his defection was perhaps of greater value to the Soviets than any information he provided. Burgess's life has frequently been fictionalised, and dramatised in productions for screen and stage.

Life

Family background

The Burgess family's English roots can be traced to the arrival in Britain in 1592 of Abraham de Bourgeous de Chantilly, a refugee from the Huguenot religious persecutions in France. The family settled in Kent, and became prosperous, mainly as bankers.[1] Later generations created a military tradition; Guy Burgess's grandfather, Henry Miles Burgess, was an officer in the Royal Artillery whose main service was in the Middle East. His youngest son, Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess, was born in Aden in 1881,[1] the third forename being a nod to his Huguenot ancestry.[2] Malcolm had a generally unremarkable career in the Royal Navy,[3] eventually reaching the rank of Commander.[2] In 1907 he married Evelyn Gillman, the daughter of a wealthy Portsmouth banker. The couple settled in the naval town of Devonport where, on 16 April 1911, their elder son was born, christened Guy Francis de Moncy. A second son, Nigel, was born two years later.[3]

Childhood and schooling

Eton College, which Burgess attended in 1924 and between 1927 and 1930

The Gillman wealth ensured a comfortable home for the young family.[4] Guy's earliest schooling was probably with a governess until, aged nine, he began as a boarder at Lockers Park, an exclusive preparatory school near Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire. He did well there; his grades were consistently good and he played for the school's association football team.[5] Having completed the Lockers curriculum a year early, he was too young to proceed immediately, as intended, to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth.[n 1] Instead, from January 1924 he spent a year at Eton College, Britain's most prestigious public school.[8]

Following Malcolm Burgess's retirement from the navy, the family moved to West Meon in Hampshire. Here, on 15 September 1924, Malcolm died suddenly of a heart attack.[9] Despite this traumatic event, Guy's education proceeded as planned, and in January 1925 he began at Dartmouth.[10][n 2] Here he encountered strict discipline and insistence on order and conformity, enforced by frequent use of corporal punishment even for minor infringements.[12] In this environment, Burgess thrived both academically and at sports.[13] He was marked by the college authorities as "excellent officer material",[14] but an eye test in 1927 exposed a deficiency that precluded a career in the navy's executive branch. Burgess had no interest in the available alternatives – the engineering or paymaster branches – and in July 1927 he left Dartmouth and returned to Eton.[15][n 3]

Burgess's second period at Eton, between 1927 and 1930, was largely rewarding and successful, both academically and socially. Although he failed to be elected to the elite society known as "Pop",[16] he began to develop a network of contacts that would prove useful in later life.[17] At Eton, sexual relationships between boys were common,[18] and although Burgess would claim that his homosexuality began at Eton, his contemporaries could recall little evidence of this.[19] Generally, Burgess was remembered as amusingly flamboyant, and something of an oddity with his professed left-wing social and political opinions.[20] In January 1930 he sat for and won a history scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, concluding his school career with further prizes in history and drawing.[21] Throughout his life he retained fond memories of Eton; according to his biographers Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert he "never showed any embarrassment that he had been educated in a citadel of educational privilege".[22]

Cambridge

Undergraduate

Burgess arrived in Cambridge in October 1930, and quickly involved himself in many aspects of student life. He was not universally liked; one contemporary described him as "a conceited unreliable shit", although others found him amusing and good company.[23] After a term, he was elected to the Trinity Historical Society whose membership was formed from the brightest of Trinity College undergraduates and postgraduates. Here he encountered Kim Philby, and also Jim Lees, a former miner studying under a trade union scholarship, whose working-class perspective Burgess found stimulating.[24] In June 1931 Burgess designed the stage sets for a student production of Bernard Shaw's play Captain Brassbound's Conversion, with Michael Redgrave in the leading role.[25][26] Redgrave considered Burgess "one of the bright stars of the university scene, with a reputation for being able to turn to anything".[27]

Great Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

Burgess by this time made no attempt to conceal his homosexuality. In 1931 he met Anthony Blunt, four years his senior and a Trinity postgraduate. The two shared artistic interests and became friends, possibly lovers.[28] Blunt was a member of the intellectual society known as the "Apostles", to which in 1932 he secured Burgess's election.[29] This gave Burgess a greatly extended range of networking opportunities;[30] membership of the Apostles was lifelong, so at the regular meetings he met many of the leading intellectuals of the day, such as G. M. Trevelyan, the University's Regius Professor of History, the writer E. M. Forster, and the economist John Maynard Keynes.[31]

In the early 1930s the general political climate was volatile and threatening. In Britain, the financial crisis of 1931 pointed to the failure of capitalism, while in Germany the rise of Nazism was a source of increasing disquiet.[32] Such events radicalised opinion in Cambridge and elsewhere;[33] according to Burgess's fellow Trinity student James Klugmann, "Life seemed to demonstrate the total bankruptcy of the capitalist system and shouted aloud for some sort of quick, rational, simple alternative".[34] Burgess's interest in Marxism, initiated by friends such as Lees, deepened after he heard the historian Maurice Dobb, a fellow of Pembroke College, address the Trinity Historical Society on the issue of "Communism: a Political and Historical Theory". Another influence was a fellow student, David Guest, a leading light in the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS), within which he formed the university's first active communist cell. Under Guest's influence, Burgess began studying the works of Marx and Lenin.[35]

Amid these political distractions, in 1932 Burgess obtained first-class honours in Part I of the history Tripos, and was expected to graduate with similar honours in Part II the following year. But although he worked hard, political activity distracted him and by the time of his final examinations in 1933 he was unprepared. During his examinations he fell ill and was unable to complete his papers; this may have been the consequence of belated cramming, or of taking amphetamines.[36] The examiners awarded him an aegrotat, an unclassified degree awarded to students considered worthy of honours but prevented through illness from completing their examinations.[37][n 4]

Postgraduate

Cambridge War Memorial, focus of demonstrations in November 1933

Despite his disappointing degree result, Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1933 as a postgraduate student and teaching assistant. His chosen research area was "Bourgeois Revolution in Seventeenth-Century England", but much of his time was devoted to political activism. That winter he formally joined the British Communist Party and became a member of its cell within CUSS.[41] On 11 November 1933 he joined a mass demonstration against the perceived militarism of the city's Armistice Day celebrations. The protestors' objective, laying a wreath bearing a pacifist message at the Cambridge War Memorial, was achieved, despite attacks and counter-demonstrations which included what the historian Martin Garrett describes as "a hail of pro-war eggs and tomatoes".[42][43] Alongside Burgess was Donald Maclean, a languages student from Trinity Hall and an active CUSS member.[44] In February 1934 Burgess, Maclean and fellow members of CUSS welcomed the Tyneside and Tees-side contingents of that month's National Hunger March, as they passed through Cambridge on their way to London.[45][44][46]

When not occupied in Cambridge, Burgess made frequent visits to Oxford, to confer with kindred spirits there; according to an Oxford student's later reminiscences, at that time "it was impossible to be in the intellectual swim ... without coming across Guy Burgess".[47] Among those he befriended was Goronwy Rees, a young Fellow of All Souls College.[48] Rees had planned to visit the Soviet Union with a fellow don in the 1934 summer vacation, but was unable to go; Burgess took his place. During the carefully escorted trip, in June–July 1934, Burgess met some notable figures, including possibly Nikolai Bukharin, editor of Izvestia and former secretary of the Comintern. On his return, Burgess had little to report, beyond commenting on the "appalling" housing conditions while praising the country's lack of unemployment.[49]

Recruitment as Soviet agent

When Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1934, his prospects of a college fellowship and an academic career were fast receding. He had abandoned his research after discovering that the same ground was covered in a new book by Basil Willey. He began an alternative study of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, but his time was largely preoccupied with politics.[50][51]

Kim Philby, as depicted on a Soviet Union stamp

Early in 1934 Arnold Deutsch, a longstanding Soviet secret agent, arrived in London under the cover of a research appointment at University College, London. Known as "Otto", his brief was to recruit the brightest students from Britain's top universities, who might in future occupy leading positions in British institutions.[52][53] In June 1934 he recruited Philby, who had come to the Soviets' notice earlier that year in Vienna where he had been involved in demonstrations against the Dollfuss government.[54] Philby recommended several of his Cambridge associates to Deutsch, including Maclean, by this time working in the Foreign Office.[55] He also recommended Burgess, although with some reservations on account of the latter's erratic personality.[56] Deutsch considered Burgess worth the risk, "an extremely well-educated fellow, with valuable social connections, and the inclinations of an adventurer".[57] Burgess was given the codename "Mädchen", meaning "Girl", later changed to "Hicks".[58] Burgess then persuaded Blunt that he could best fight fascism by working for the Soviets.[59] A few years later another Apostle, John Cairncross, was recruited by Burgess and Blunt, to complete the spy ring often characterised as the "Cambridge Five".[60][61][n 5]

Finally recognising that he had no future career at Cambridge, Burgess left in April 1935.[63] The long-term aim of the Soviet intelligence services[n 6] was for Burgess to penetrate British intelligence,[65] and with this in mind he needed to publicly distance himself from his communist past. Thus he resigned his Communist Party membership and publicly renounced communism, with a gusto that shocked and dismayed his former comrades.[66][67] He then looked for suitable work, applying without success for positions with the Conservative Research Department and Conservative Central Office.[63] He sought a teaching job at Eton, but was rejected when a request for information from his former Cambridge tutor received the reply: "I would very much prefer not to answer your letter".[68]

Late in 1935 Burgess accepted a temporary post as personal assistant to John Macnamara, the recently elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Chelmsford. Macnamara was on the right of his party; he and Burgess joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, which promoted friendship with Nazi Germany. This enabled Burgess to disguise his political past very effectively, while gathering important information about Germany's foreign policy intentions.[69] Within the Fellowship, Burgess would proclaim fascism as "the wave of the future", although in other forums such as the Apostles he was more circumspect.[70] The association with Macnamara involved several trips to Germany; some, by Burgess's own later version of events, of a decidedly dissolute nature – both men were practising homosexuals.[71] These stories, according to the historian Michael Holzman, may have been invented or exaggerated to draw attention away from Burgess's true motives.[72]

In the autumn of 1936 Burgess met the nineteen-year-old Jack Hewit in The Bunch of Grapes, a well-known homosexual bar in The Strand. Hewit, a would-be dancer seeking work in London's musical theatres, would be Burgess's friend, manservant and intermittent lover for the next fourteen years,[73] generally sharing Burgess's various London homes: Chester Square from 1936 to 1941, Bentinck Street from 1941 to 1947, and New Bond Street from 1947 until 1951.[74][75]

BBC and MI6

BBC: first stint

In July 1936, having twice previously applied unsuccessfully for posts at the BBC, Burgess was appointed as an assistant producer in the Corporation's Talks Department.[76] Responsible for selecting and interviewing potential speakers for current affairs and cultural programmes, he drew on his extensive range of personal contacts and rarely met refusal.[77] His relationships at the BBC were volatile; he quarrelled with management about his pay,[78][79] while colleagues were irritated by his opportunism, his capacity for intrigue,[77] and his slovenliness. One colleague, Gorley Putt, remembered him as "a snob and a slob ... It amazed me, much later in life, to learn that he had been irresistibly attractive to most people he met".[80]

Old Broadcasting House, BBC's London HQ from 1932 (photographed in 2007)

Among those Burgess invited to broadcast were Blunt, several times, the well-connected writer-politician Harold Nicolson (a fruitful source of high-level gossip), the poet John Betjeman, and Kim Philby's father, the Arabist and explorer St John Philby.[81] Burgess also sought out Winston Churchill, then a powerful backbench opponent of the government's appeasement policy. On 1 October 1938, during the Munich crisis, Burgess, who had met Churchill socially, went to the latter's home at Chartwell to persuade him to reconsider his decision to withdraw from a projected talks series on Mediterranean countries.[82][83] According to the account provided in Tom Driberg's biography, the conversation ranged over a series of issues, with Burgess urging the statesman to "offer his eloquence" to help resolve the current crisis. The meeting ended with the presentation to Burgess of a signed copy of Churchill's book Arms and the Covenant,[84] but the broadcast did not take place.[85]

Pursuing their main objective, the penetration of the British intelligence agencies, Burgess's controllers asked him to cultivate a friendship with the author David Footman, who they knew was an MI6 officer. Footman introduced Burgess to his superior, Valentine Vivian; as a result, over the following eighteen months Burgess carried out several small assignments for MI6 on an unpaid freelance basis.[86] He was trusted sufficiently to be used as a back channel of communication between the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, and his French counterpart Edouard Daladier, during the period leading to the 1938 Munich summit.[87]

At the BBC, Burgess thought his choices of speaker were being undermined by the BBC's subservience to the government – he attributed Churchill's non-appearance to this – and in November 1938, after another of his speakers was withdrawn at the request of the prime minister's office, he resigned.[88] MI6 was by now convinced of his future utility, and he accepted a job with its new propaganda division, known as Section D.[89] In common with the other members of the Cambridge Five, his entry to British intelligence was achieved without vetting; his social position and personal recommendation were considered sufficient.[90]

Section D

Foreign ministers Molotov (left) and Ribbentrop at the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact

Section D was established by MI6 in March 1938, as a secret organisation charged with investigating how enemies might be attacked other than through military operations.[91] Burgess acted as Section D's representative on the Joint Broadcasting Committee (JBC), a body set up by the Foreign Office to liaise with the BBC over the transmission of anti-Hitler broadcasts to Germany.[92] His contacts with senior government officials enabled him to keep Moscow abreast of current government thinking. He informed them that the British government saw no need for a pact with the Soviets, since they believed Britain alone could defeat the Germans without Russian assistance.[93][94] This information reinforced the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's suspicions of Britain, and may have helped to hasten the Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939.[95]

After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Burgess, with Philby who had been brought into Section D on his recommendation,[96] ran a training course for would-be saboteurs, at Brickendonbury Manor in Hertfordshire. Philby later was sceptical of the value of such training, since neither he nor Burgess had any idea of the tasks these agents would be expected to perform behind the lines in German-occupied Europe.[97] In 1940, Section D was absorbed into the new Special Operations Executive (SOE). Philby was posted to a SOE training school in Beaulieu, and Burgess, who in September had been arrested for drunken driving (the charge was dismissed on payment of costs), found himself at the end of the year out of a job.[98]

BBC: second stint

In mid-January 1941 Burgess rejoined the BBC Talks Department,[99] while continuing to carry out freelance intelligence work, both for MI6[100] and its domestic intelligence counterpart MI5, which he had joined in a supernumerary capacity in 1940.[101] After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the BBC required Burgess to select speakers who would depict Britain's new Soviet ally in a favourable light.[102][103][104] He turned again to Blunt, and to his old Cambridge friend Jim Lees,[105] and in 1942 arranged a broadcast by Ernst Henri, a Soviet agent masquerading as a journalist. No transcript of Henri's talk survives, but listeners remembered it as pure Soviet propaganda.[106] In October 1941 Burgess took charge of the flagship political programme The Week in Westminster, which gave him almost unlimited access to Parliament.[107] Information gleaned from regular wining, lunching and gossiping with MPs was invaluable to the Soviets, regardless of the content of the programmes that resulted.[108] Burgess sought to maintain a political balance; his fellow Etonian Quintin Hogg, a future Conservative Lord Chancellor, was a regular broadcaster,[109] as, from the opposite social and political spectrum, was Hector McNeil, a former journalist who became a Labour MP in 1941 and served as a parliamentary private secretary in the Churchill war ministry.[110]

Burgess had lived in a Chester Square flat since 1935.[111] From Easter 1941 he shared a house with Blunt and others at No. 5 Bentinck Street.[112] Here, Burgess maintained an active social life with his many acquaintances, both regular and casual;[n 7] Goronwy Rees likened the Bentinck Street ambience to that of a French farce: "Bedroom doors opened and shut, strange faces appeared and disappeared down the stairs where they passed some new visitor coming up..."[114] This account was disputed by Blunt, who claimed that such casual comings and goings were contrary to house rules, since they would have disrupted other tenants' sleep.[115]

Burgess's casual work for MI5 and MI6 deflected official suspicion as to his true loyalties,[116] but he lived in constant fear of exposure, particularly as he had revealed the truth to Rees, when trying to recruit the latter in 1937.[117][118] Rees had since renounced communism, and was serving as an officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers.[119] Believing that Rees might expose him and others, Burgess suggested to his handlers that they should kill Rees, or alternatively that he should do the job himself. Nothing came of this proposal.[120][121] Always seeking ways of further penetrating the citadels of power, when in June 1944 Burgess was offered a job in the News Department of the Foreign Office, he accepted it.[122] The BBC reluctantly assented to his release, stating that his departure would be "a serious loss".[123]

Foreign Office

London

As a press officer in the Foreign Office News Department, Burgess's role involved explaining government policy to foreign editors and diplomatic correspondents.[124] His access to secret material enabled him to send Moscow important details of allied policy both before and during the March 1945 Yalta Conference.[125] He passed information relating to the postwar futures of Poland and Germany, and also contingency plans for "Operation Unthinkable", which anticipated a future war with the Soviet Union.[126] His Soviet masters rewarded his efforts with a £250 bonus.[58][n 8] Burgess's working methods were characteristically disorganised, and his tongue was loose; according to his colleague Osbert Lancaster, "[w]hen in his cups he made no bones about working for the Russians".[128]

"Burgess saw almost all material produced by the Foreign Office, including telegraphic communications both decoded and encoded, with keys for decryption, which would have been valuable to his Soviet handlers".

-- Lownie: Stalin's Englishman[124]

Burgess had maintained contact with McNeil who, following Labour's victory in the 1945 General Election, became Minister of State at the Foreign Office, effectively Ernest Bevin's deputy. McNeil, a staunch anti-communist unsuspecting of Burgess's true allegiance, admired the latter for his sophistication and intelligence, and in December 1946 secured his services as an additional private secretary.[129] The appointment was in breach of regular Foreign Office procedures, and there were complaints, but McNeil prevailed.[130] Burgess quickly made himself indispensable to McNeil,[131] and in one six-month period transmitted to Moscow the contents of 693 files, a total of over 2,000 photographed pages, for which he received a further cash reward of £200.[132][n 9]

Early in 1948 Burgess was seconded to the Foreign Office's newly created Information Research Department (IRD), set up to counteract Soviet propaganda.[133] The move was not a success; he was indiscreet, and his new colleagues thought him "dirty, drunken and idle".[134] He was quickly sent back to McNeil's office, and in March 1948 accompanied McNeil and Bevin to Brussels for the signing of the Treaty of Brussels, which eventually led to the establishment of the Western European Union and NATO.[135] He remained with McNeil until October 1948, when he was posted to the Foreign Office's Far East Department.[136] Burgess was assigned to the China desk at a point when the Chinese civil war was nearing its climax, a communist victory imminent. There were important differences of view between Britain and the U.S. on future diplomatic relations with the forthcoming communist state.[137] Burgess was a forceful advocate for recognition, and may have influenced Britain's decision to recognise communist China in 1949.[138]

In February 1949, a fracas at a West End Club – possibly the RAC – resulted in a fall downstairs that left Burgess with severe head injuries, following which he was hospitalised for several weeks.[137][139] Recovery was slow; according to Holzman he never functioned well after that.[140] Nicolson noted the decline: "Oh my dear, what a sad, sad thing this constant drinking is! Guy used to have one of the most rapid and active minds I knew".[141] Later in 1949 a holiday in Gibraltar and North Africa became a catalogue of drunkenness, promiscuous sex, and arguments with diplomatic and MI6 staff, exacerbated by the frankly homophobic attitudes towards Burgess by some local officials.[142][143] Back in London, Burgess was reprimanded,[144] but somehow retained the confidence of his superiors, so that his next posting, in July 1950, was to Washington, as second secretary in what Purvis and Hulbert describe as "one of the UK's highest profile embassies, the creme de la creme of diplomatic postings".[145]

Washington

Anthony Eden, Burgess's "guest"

Philby had preceded Burgess to Washington, and was serving there as local head of MI6,[146] following in the path of Maclean who had worked as the embassy's first secretary between 1944 and 1948.[147][n 10] Burgess soon reverted to his erratic and intemperate habits, causing regular embarrassment in British diplomatic circles.[149][150][151] Despite this, he was given work of top secret sensitivity. Among his duties he served on the inter-allied board responsible for the conduct of the Korean War, which gave him access to America's strategic war plans.[149] His frequent behavioural lapses did not prevent his being chosen to act as escort to Anthony Eden, when the future British prime minister visited Washington in November 1950. The episode passed without trouble; the two, both Etonians, got on well, and Burgess received a warm letter of thanks from Eden "for all your kindness".[152]

Increasingly, Burgess was dissatisfied with his job. He considered leaving the diplomatic service altogether, and began sounding out his Eton friend Michael Berry about a journalistic post on The Daily Telegraph.[153] Early in 1951 a series of indiscretions, including three speeding tickets on a single day, made his position at the embassy untenable, and he was ordered by the ambassador, Sir Oliver Franks, to return to London.[154][n 11] Meanwhile, the U.S. Army's Venona counterintelligence project, investigating the identity of a Soviet spy codenamed "Homer" who had been active in Washington a few years earlier, had unearthed strong evidence that pointed to Donald Maclean. Philby and his Soviet spymasters believed that Maclean might crack when confronted by British intelligence, and expose the entire Cambridge ring.[156] Burgess was thus given the task, on reaching London, of organising Maclean's defection to the Soviet Union.[157]

Defection

Departure

Burgess returned to England on 7 May 1951. He and Blunt then contacted Yuri Modin, the Soviet spymaster in charge of the Cambridge ring, who began arrangements with Moscow to receive Maclean.[158][159] Burgess showed little urgency in proceeding with the matter,[160] finding time to pursue his personal affairs and attend an Apostles dinner in Cambridge.[161][162] On 11 May he was summoned to the Foreign Office to answer for his misconduct in Washington and, according to Boyle, was dismissed.[163] Other commentators say he was invited to resign or "retire", and was given time to consider his position.[161][164]

Burgess's diplomatic career was over, although he was not at this stage under any suspicion of treachery. He met with Maclean several times; according to Burgess's 1956 account to Driberg, the question of defection to Moscow was not raised until their third meeting, when Maclean said he was going and requested Burgess's help.[165] Burgess had previously promised Philby that he would not go with Maclean, since a double defection would put Philby's own position in serious jeopardy.[166] Blunt's unpublished memoirs state that it was Moscow's decision to send Burgess with Maclean who, they thought, would be unable to handle the complicated escape arrangements alone.[167] Burgess told Driberg that he had agreed to accompany Maclean because he was leaving the Foreign Office anyway, "and I probably couldn't stick the job at the Daily Telegraph".[165]

SS Falaise, the ship on which Burgess and Maclean fled in May 1951

Meanwhile, the Foreign Office had fixed Monday 28 May as the date for confronting Maclean with their suspicions. Philby notified Burgess who, on Friday 25 May, bought two tickets for a weekend channel cruise on the steamship Falaise.[168] These short cruises docked at the French port of St Malo, where passengers could disembark for a few hours without passport checks.[169] Burgess also hired a saloon car, and that evening drove to Maclean's house at Tatsfield in Surrey, where he introduced himself to Maclean's wife Melinda as "Roger Styles".[n 12] After the three had dined, Burgess and Maclean drove rapidly to Southampton, boarding the Falaise just before its midnight departure – the hired car was left abandoned on the quayside.[168]

The pair's subsequent movements were revealed later. On arrival in St Malo they took a taxi to Rennes, then travelled by rail to Paris and on to Berne in Switzerland. Here, by prior arrangement, they were issued with papers at the Soviet embassy, before travelling to Zurich, where they caught a flight to Prague. Safely behind the Iron Curtain, they were able to proceed smoothly on the final stages of their journey to Moscow.[169]

Aftermath

On Saturday 26 May, Hewit informed a friend that Burgess had not come home the previous night. Since Burgess never went away without telling his mother, his absence caused some anxiety in his circle.[170] Maclean's non-appearance at his desk on the following Monday raised concerns that he might have absconded. Disquiet increased when officials realised that Burgess, too, was missing; the discovery of the abandoned car, hired in Burgess's name, together with Melinda Maclean's revelations about "Roger Styles", confirmed that both had fled.[169] Blunt quickly visited Burgess's flat in New Bond Street and removed incriminating materials.[171] An MI6 search of the flat revealed papers that compromised another member of the Cambridge ring, Cairncross, who was later required to resign from his civil service post.[172]

The news of the double flight alarmed the Americans, following the recent conviction of the atomic spy Klaus Fuchs, and the defection of the physicist Bruno Pontecorvo the previous year.[173][174] Aware that his own position was now precarious, Philby recovered various spying paraphernalia from Burgess's former Washington quarters, and buried them in a nearby wood.[175] Summoned to London in June 1951, he was interrogated for several days by MI6. There were strong suspicions that he was responsible for forewarning Maclean via Burgess, but in the absence of conclusive evidence he faced no action and was permitted to retire quietly from MI6.[176]

In the immediate aftermath the Foreign Office made nothing public.[177] In private circles, many rumours abounded: the pair had been kidnapped by the Russians, or by the Americans, or were replicating the flight of Rudolf Hess to Scotland in 1941 in an unofficial peace mission.[178] The press was suspicious, and the story finally broke in the Daily Express on 7 June.[179] A cautious Foreign Office statement then confirmed that Maclean and Burgess were missing and were being treated as absent without leave.[180] In the House of Commons the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison, said there was no indication that the missing diplomats had taken secret documents with them, nor would he attempt to prejudge the issue of their destination.[181]

On 30 June the Express offered a reward of £1,000 for information on the diplomats' current whereabouts, an amount dwarfed shortly afterwards by the Daily Mail's offer of £10,000.[182] There were numerous false sightings in the months that followed. Some press reports speculated that Burgess and Maclean were being held in Moscow's Lubyanka prison.[182] Harold Nicolson thought the Soviets would "use [Burgess] for a month or so and then quietly shove him into some salt mine".[183] Just before Christmas 1953, Burgess's mother received a letter from her son, postmarked in South London. The letter, full of affection and messages for his friends, revealed nothing of his location or circumstances.[184] In April 1954 a senior MGB officer, Vladmir Petrov, defected in Australia. He brought with him papers indicating that Burgess and Maclean had been Soviet agents since their Cambridge days, that the MGB had masterminded their escape,[185] and that they were alive and well in the Soviet Union.[186]