Kim Philbyby Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/22/20

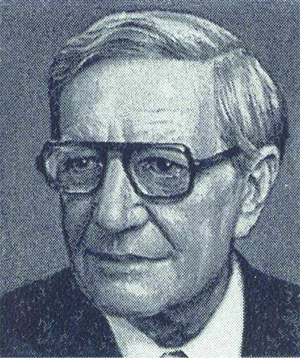

Kim Philby

Born: Harold Adrian Russell Philby, 1 January 1912, Ambala, Punjab, British IndiaDied: 11 May 1988 (aged 76), Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union

Burial place: Kuntsevo Cemetery, Ryabinovaya Ulitsa, Moscow

Nationality: British

Alma mater: Trinity College, Cambridge

Spouse(s): Litzi Friedmann; Aileen Furse; Eleanor Brewer; Rufina Ivanovna Pukhova

Parent(s): St John Philby; Dora Philby

Espionage activity

Allegiance: Soviet Union

Codename: Sonny, Stanley

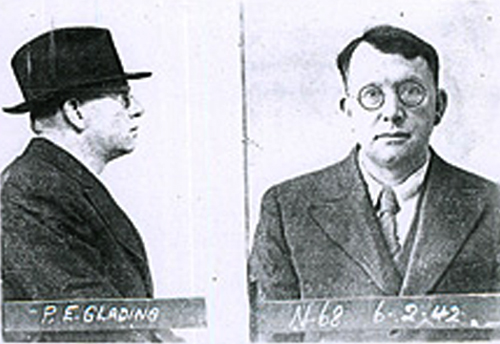

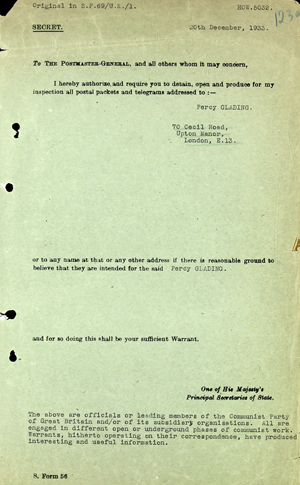

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 1912 – 11 May 1988)[1] was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963, he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II and in the early stages of the Cold War. Of the five, Philby is believed to have been most successful in providing secret information to the Soviets.[2]Born in British India, Philby was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was recruited by Soviet intelligence in 1934.

After leaving Cambridge, Philby worked as a journalist and covered the Spanish Civil War and the Battle of France. In 1940, he began working for MI6. By the end of the Second World War he had become a high-ranking member of the British intelligence service. In 1949, Philby was appointed first secretary to the British Embassy in Washington and served as chief British liaison with American intelligence agencies. During his career as an intelligence officer, he passed large amounts of intelligence to the Soviet Union, including an Anglo-American plot to subvert the communist regime of Albania. He was also responsible for tipping off two other spies under suspicion of espionage, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, both of whom subsequently fled to Moscow in May 1951.

The defections of Maclean and Burgess cast suspicion over Philby, resulting in his resignation from MI6 in July 1951. He was publicly exonerated in 1955, after which he resumed his career in journalism in Beirut. In January 1963, having finally been unmasked as a Soviet agent, Philby defected to Moscow, where he lived out his life until his death in 1988.Early lifeBorn in Ambala, Punjab, British India, Philby was the son of Dora Johnston and St John Philby, an author, Arabist and explorer.[3] St John was a member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and later a civil servant in Mesopotamia and advisor to King Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia.[4]Nicknamed "Kim" after the boy-spy in Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim,[3] Philby attended Aldro preparatory school, an all boys school located in Shackleford near Godalming in Surrey, United Kingdom. In his early teens, he spent some time with the Bedouin in the desert of Saudi Arabia.[5] Following in the footsteps of his father, Philby continued to Westminster School, which he left in 1928 at the age of 16. He won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied history and economics. He graduated in 1933 with a 2:1 degree in Economics.[6]

Upon Philby's graduation, Maurice Dobb, a fellow of King's College, Cambridge and tutor in Economics, introduced him to the World Federation for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism in Paris. The World Federation for the Relief of the Victims of German Fascism was an organization that attempted to aid the people victimized by fascism in Germany and provide education on oppositions to fascism. The organization was one of several fronts operated by German Communist Willi Münzenberg, a member of the Reichstag who had fled to France in 1933.[7]

Early professional career

ViennaIn Vienna, working to aid refugees from Nazi Germany, Philby met and fell in love with Litzi Friedmann (born Alice Kohlmann), a young Austrian Communist of Hungarian Jewish origins. Philby admired the strength of her political convictions and later recalled that at their first meeting:

[a] frank and direct person, Litzi came out and asked me how much money I had. I replied £100, which I hoped would last me about a year in Vienna. She made some calculations and announced, "That will leave you an excess of £25. You can give that to the International Organisation for Aid for Revolutionaries. We need it desperately." I liked her determination.[8]

He acted as a courier between Vienna and Prague, paying for the train tickets out of his remaining £75 and using his British passport to evade suspicion. He also delivered clothes and money to refugees from the Nazis.[9]

Following the Austrofascist victory in the Austrian Civil War, Friedmann and Philby married in February 1934, enabling her to escape to the United Kingdom with him two months later.[9] It is possible that it was a Viennese-born friend of Friedmann's in London, Edith Tudor Hart – herself, at this time, a Soviet agent – who first approached Philby about the possibility of working for Soviet intelligence.[9]

In early 1934, Arnold Deutsch, a Soviet agent, was sent to University College London under the cover of a research appointment. His intention was to recruit the brightest students from Britain's top universities.[10][11] Philby had come to the Soviets' notice earlier that year in Vienna, where he had been involved in demonstrations against the government of Engelbert Dollfuss. In June 1934, Deutsch recruited him to the Soviet intelligence services.[12] Philby later recalled:

Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a "man of decisive importance". I questioned her about it but she would give me no details. The rendezvous took place in Regents Park. The man described himself as Otto. I discovered much later from a photograph in MI5 files that the name he went by was Arnold Deutsch. I think that he was of Czech origin; about 5 ft 7in, stout, with blue eyes and light curly hair. Though a convinced Communist, he had a strong humanistic streak. He hated London, adored Paris, and spoke of it with deeply loving affection. He was a man of considerable cultural background."[13]

Philby recommended to Deutsch several of his Cambridge contemporaries, including Donald Maclean, who at the time was working in the Foreign Office,[14] as well as Guy Burgess, despite his personal reservations about Burgess' erratic personality.[15]

London and SpainIn London, Philby began a career as a journalist. He took a job at a monthly magazine, the World Review of Reviews, for which he wrote a large number of articles and letters (sometimes under a variety of pseudonyms) and occasionally served as "acting editor."[16]

Philby continued to live in the United Kingdom with his wife for several years. At this point, however, Philby and Litzi separated. They remained friends for many years following their separation and divorced only in 1946, just following the end of World War II. When the Germans threatened to overrun Paris in 1940, where she was then living at this time, he arranged for her escape to Britain. In 1936 he began working at a trade magazine, the Anglo-Russian Trade Gazette, as editor. The paper was failing and its owner changed the paper's role to covering Anglo-German trade. Philby engaged in a concerted effort to make contact with Germans such as Joachim von Ribbentrop, at that time the German ambassador in London. He became a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship, an organization aiming at rebuilding and supporting a friendly relationship between Germany and the United Kingdom. The Anglo-German Fellowship, at this time, was supported both by the British and German governments, and Philby made many trips to Berlin.[9]

In February 1937, Philby travelled to Seville, Spain, then embroiled in a bloody civil war triggered by the coup d'état of Fascist forces under General Francisco Franco against the democratic government of President Manuel Azaña. Philby worked at first as a freelance journalist; from May 1937, he served as a first-hand correspondent for The Times, reporting from the headquarters of the pro-Franco forces. He also began working for both the Soviet and British intelligence, which usually consisted of posting letters in a crude code to a fictitious girlfriend, Mlle Dupont in Paris, for the Russians. He used a simpler system for MI6 delivering post at Hendaye, France, for the British Embassy in Paris. When visiting Paris after the war, he was shocked to discover that the address that he used for Mlle Dupont was that of the Soviet Embassy. His controller in Paris, the Latvian Ozolin-Haskins (code name Pierre), was shot in Moscow in 1937 during Stalin's purge. His successor, Boris Bazarov, suffered the same fate two years later during the purges.[9]

Both the British and the Soviets were interested in the combat performance of the new Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Panzer I and IIs deployed with Fascist forces in Spain. Philby told the British, after a direct question to Franco, that German troops would never be permitted to cross Spain to attack Gibraltar.[9]

His Soviet controller at the time, Theodore Maly, reported in April 1937 to the NKVD that he had personally briefed Philby on the need "to discover the system of guarding Franco and his entourage".[17] Maly was one of the Soviet Union's most powerful and influential illegal controllers and recruiters. With the goal of potentially arranging Franco's assassination, Philby was instructed to report on vulnerable points in Franco's security and recommend ways to gain access to him and his staff.[18] However, such an act was never a real possibility; upon debriefing Philby in London on 24 May 1937, Maly wrote to the NKVD, "Though devoted and ready to sacrifice himself, [Philby] does not possess the physical courage and other qualities necessary for this [assassination] attempt."[18]

In December 1937, during the Battle of Teruel, a Republican shell hit just in front of the car in which Philby was travelling with the correspondents Edward J. Neil of the Associated Press, Bradish Johnson of Newsweek, and Ernest Sheepshanks[19] of Reuters. Johnson was killed outright, and Neil and Sheepshanks soon died of their injuries. Philby suffered only a minor head wound. As a result of this accident, Philby, who was well-liked by the Nationalist forces whose victories he trumpeted, was awarded the Red Cross of Military Merit by Franco on 2 March 1938. Philby found that the award proved helpful in obtaining access to fascist circles:

"Before then," he later wrote, "there had been a lot of criticism of British journalists from Franco officers who seemed to think that the British in general must be a lot of Communists because so many were fighting with the International Brigades. After I had been wounded and decorated by Franco himself, I became known as 'the English-decorated-by-Franco' and all sorts of doors opened to me."[18]

In 1938, Walter Krivitsky (born Samuel Ginsberg), a former GRU officer in Paris who had defected to France the previous year, travelled to the United States and published an account of his time in "Stalin's secret service". He testified before the Dies Committee (later to become the House Un-American Activities Committee) regarding Soviet espionage within the United States. In 1940 he was interviewed by MI5 officers in London, led by Jane Archer. Krivitsky claimed that two Soviet intelligence agents had penetrated the British Foreign Office and that a third Soviet intelligence agent had worked as a journalist for a British newspaper during the civil war in Spain. No connection with Philby was made at the time, and Krivitsky was found shot in a Washington hotel room the following year.[20][21]

Alexander Orlov (born Lev Feldbin; code-name Swede), Philby's controller in Madrid, who had once met him in Perpignan, France, with the bulge of an automatic rifle clearly showing through his raincoat, also defected. To protect his family, still living in the USSR, he said nothing about Philby, an agreement Stalin respected.[9] On a short trip back from Spain, Philby tried to recruit Flora Solomon as a Soviet agent; she was the daughter of a Russian banker and gold dealer, a relative of the Rothschilds, and wife of a London stockbroker. At the same time, Burgess was trying to get her into MI6. But the resident (Russian term for spymaster) in France, probably Pierre at this time, suggested to Moscow that he suspected Philby's motives. Solomon introduced Philby to his second wife, Aileen Furse, but went to work for the British retailer Marks & Spencer.[9]

MI6 career

World War IIIn July 1939, Philby returned to The Times office in London. When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Philby's contact with his Soviet controllers was lost and Philby failed to attend the meetings that were necessary for his work. During the Phoney War from September 1939 until the Dunkirk evacuation, Philby worked as The Times first-hand correspondent with the British Expeditionary Force headquarters.[9] After being evacuated from Boulogne on 21 May, he returned to France in mid-June and began representing The Daily Telegraph in addition to The Times. He briefly reported from Cherbourg and Brest, sailing for Plymouth less than twenty-four hours before the French surrendered to Germany in June 1940.[22]

In 1940, on the recommendation of Burgess, Philby joined MI6's Section D, a secret organisation charged with investigating how enemies might be attacked through non-military means.[23][24] Philby and Burgess ran a training course for would-be saboteurs at Brickendonbury Manor in Hertfordshire.[25] His time at Section D, however, was short-lived; the "tiny, ineffective, and slightly comic" section[26] was soon absorbed by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in the summer of 1940. Burgess was arrested in September for drunken driving and was subsequently fired,[27] while Philby was appointed as an instructor on clandestine propaganda at the SOE's finishing school for agents at the Estate of Lord Montagu[28] in Beaulieu, Hampshire.[29]

Philby's role as an instructor of sabotage agents again brought him to the attention of the Soviet Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU). This role allowed him to conduct sabotage and instruct agents on how to properly conduct sabotage. The new London rezident, Ivan Chichayev (code-name Vadim), re-established contact and asked for a list of names of British agents being trained to enter the USSR. Philby replied that none had been sent and that none were undergoing training at that time. This statement was underlined twice in red and marked with two question marks, clearly indicating their confusion and questioning of this, by disbelieving staff at Moscow Central in the Lubyanka, according to Genrikh Borovik, who saw the telegrams much later in the KGB archives.[9]

Philby provided Stalin with advance warning of Operation Barbarossa and of the Japanese intention to strike into southeast Asia instead of attacking the USSR as Hitler had urged. The first was ignored as a provocation, but the second, when this was confirmed by the Russo-German journalist and spy in Tokyo, Richard Sorge, contributed to Stalin's decision to begin transporting troops from the Far East in time for the counteroffensive around Moscow.[9]

By September 1941, Philby began working for Section Five of MI6, a section responsible for offensive counter-intelligence. On the strength of his knowledge and experience of Franco's Spain, Philby was put in charge of the subsection which dealt with Spain and Portugal. This entailed responsibility for a network of undercover operatives in several cities such as Madrid, Lisbon, Gibraltar and Tangier.[30] At this time, the German Abwehr was active in Spain, particularly around the British naval base of Gibraltar, which its agents hoped to watch with many cameras and radars to track Allied supply ships in the Western Mediterranean. Thanks to British counter-intelligence efforts, of which Philby's Iberian subsection formed a significant part, the project (code-named Bodden) never came to fruition.[31]

During 1942–43, Philby's responsibilities were then expanded to include North Africa and Italy, and he was made the deputy head of Section Five under Major Felix Cowgill, an army officer seconded to SIS.[32] In early 1944, as it became clear that the Soviet Union was likely to once more prove a significant adversary to Britain, SIS re-activated Section Nine, which dealt with anti-communist efforts. In late 1944 Philby, on instructions from his Soviet handler, maneuvered through the system successfully to replace Cowgill as head of Section Nine.[33][34] Charles Arnold-Baker, an officer of German birth (born Wolfgang von Blumenthal) working for Richard Gatty in Belgium and later transferred to the Norwegian/Swedish border, voiced many suspicions of Philby and Philby's intentions but was ignored time and time again.[citation needed]

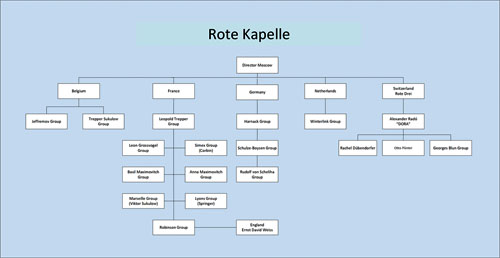

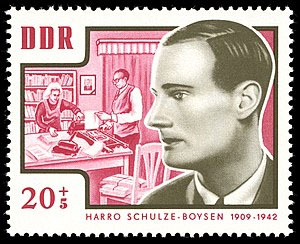

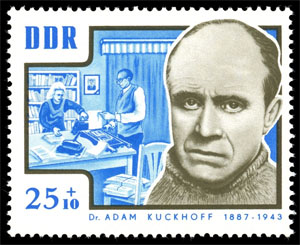

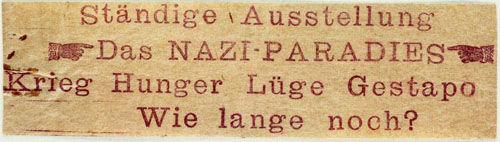

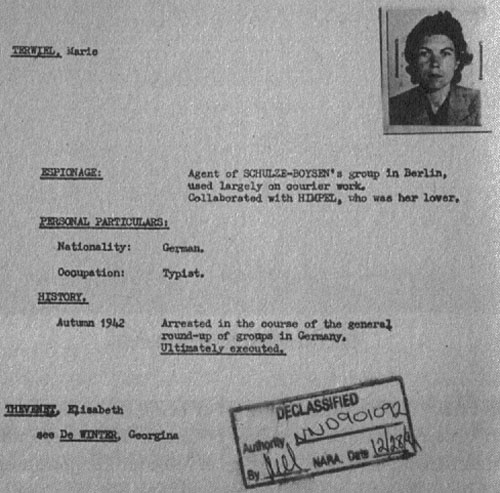

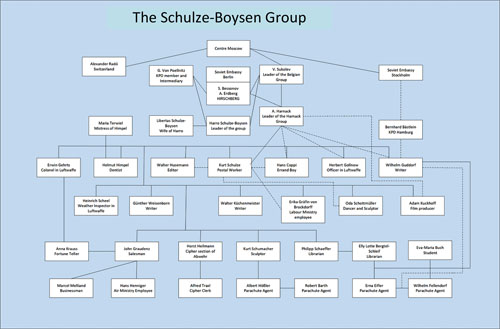

While working in Section Five, Philby had become acquainted with James Jesus Angleton, a young American counter-intelligence officer working in liaison with SIS in London. Angleton, later chief of the Central Intelligence Agency's (CIA) Counterintelligence Staff, became suspicious of Philby when he failed to pass on information relating to a British agent executed by the Gestapo in Germany. It later emerged that the agent – known as Schmidt – had also worked as an informant for the Rote Kapelle organisation, which sent information to both London and Moscow.[35] Nevertheless, Angleton's suspicions went unheard.

In late summer 1943, the SIS provided the GRU an official report on the activities of German agents in Bulgaria and Romania, soon to be invaded by the Soviet Union. The NKVD complained to Cecil Barclay, the SIS representative in Moscow, that information had been withheld. Barclay reported the complaint to London. Philby claimed to have overheard discussion of this by chance and sent a report to his controller. This turned out to be identical with Barclay's dispatch, convincing the NKVD that Philby had seen the full Barclay report. A similar lapse occurred with a report from the Imperial Japanese Embassy in Moscow sent to Tokyo. The NKVD received the same report from Richard Sorge but with an extra paragraph claiming that Hitler might seek a separate peace with the Soviet Union. These lapses by Philby aroused intense suspicion in Moscow.

Elena Modrzhinskaya at GUGB headquarters in Moscow assessed all material from the Cambridge Five. She noted that they produced an extraordinary wealth of information on German war plans but next to nothing on the repeated question of British penetration of Soviet intelligence in either London or Moscow. Philby had repeated his claim that there were no such agents. She asked, "Could the SIS really be such fools they failed to notice suitcase-loads of papers leaving the office? Could they have overlooked Philby's Communist wife?" Modrzhinskaya concluded that all were double agents, working essentially for the British.[9]

A more serious incident occurred in August 1945, when Konstantin Volkov, an NKVD agent and vice-consul in Istanbul, requested political asylum in Britain for himself and his wife. For a large sum of money, Volkov offered the names of three Soviet agents inside Britain, two of whom worked in the Foreign Office and a third who worked in counter-espionage in London. Philby was given the task of dealing with Volkov by British intelligence. He warned the Soviets of the attempted defection and travelled personally to Istanbul – ostensibly to handle the matter on behalf of SIS but, in reality, to ensure that Volkov had been neutralised. By the time he arrived in Turkey, three weeks later, Volkov had been removed to Moscow.

The intervention of Philby in the affair and the subsequent capture of Volkov by the Soviets might have seriously compromised Philby's position. However, Volkov's defection had been discussed with the British Embassy in Ankara on telephones which turned out to have been tapped by Soviet intelligence. Additionally, Volkov had insisted that all written communications about him take place by bag rather than by telegraph, causing a delay in reaction that might plausibly have given the Soviets time to uncover his plans. Philby was thus able to evade blame and detection.[36]

A month later Igor Gouzenko, a cipher clerk in Ottawa, took political asylum in Canada and gave the Royal Canadian Mounted Police names of agents operating within the British Empire that were known to him. When Jane Archer (who had interviewed Krivitsky) was appointed to Philby's section he moved her off investigatory work in case she became aware of his past. He later wrote "she had got a tantalising scrap of information about a young English journalist whom the Soviet intelligence had sent to Spain during the Civil War. And here she was plunked down in my midst!"[21]

Philby, "employed in a Department of the Foreign Office", was awarded the Order of the British Empire in 1946.[37]

IstanbulIn February 1947, Philby was appointed head of British intelligence for Turkey, and posted to Istanbul with his second wife, Aileen, and their family. His public position was that of First Secretary at the British Consulate; in reality, his intelligence work required overseeing British agents and working with the Turkish security services.[38]

Philby planned to infiltrate five or six groups of émigrés into Soviet Armenia or Soviet Georgia. But efforts among the expatriate community in Paris produced just two recruits. Turkish intelligence took them to a border crossing into Georgia but soon afterwards shots were heard. Another effort was made using a Turkish gulet for a seaborne landing, but it never left port. He was implicated in a similar campaign in Albania. Colonel David Smiley, an aristocratic Guards officer who had helped Enver Hoxha and his Communist guerillas to liberate Albania, now prepared to remove Hoxha. He trained Albanian commandos – some of whom were former Nazi collaborators – in Libya or Malta. From 1947, they infiltrated the southern mountains to build support for former King Zog.

The first three missions, overland from Greece, were trouble-free. Larger numbers were landed by sea and air under Operation Valuable, which continued until 1951, increasingly under the influence of the newly formed CIA. Stewart Menzies, head of SIS, disliked the idea, which was promoted by former SOE men now in SIS. Most infiltrators were caught by the Sigurimi, the Albanian Security Service.[39] Clearly there had been leaks and Philby was later suspected as one of the leakers. His own comment was "I do not say that people were happy under the regime but the CIA underestimated the degree of control that the Authorities had over the country."[9] Macintyre (2014) includes this typically cold-blooded quote from Philby:

The agents we sent into Albania were armed men intent on murder, sabotage and assassination ... They knew the risks they were running. I was serving the interests of the Soviet Union and those interests required that these men were defeated. To the extent that I helped defeat them, even if it caused their deaths, I have no regrets.

Aileen Philby had suffered since childhood from psychological problems which caused her to inflict injuries upon herself. In 1948, troubled by the heavy drinking and frequent depressions that had become a feature of her husband's life in Istanbul, she experienced a breakdown of this nature, staging an accident and injecting herself with urine and insulin to cause skin disfigurations.[40] She was sent to a clinic in Switzerland to recover. Upon her return to Istanbul in late 1948, she was badly burned in an incident with a charcoal stove and returned to Switzerland. Shortly afterward, Philby was moved to the job as chief SIS representative in Washington, D.C., with his family.

Washington, D.C.In September 1949, the Philbys arrived in the United States. Officially, his post was that of First Secretary to the British Embassy; in reality, he served as chief British intelligence representative in Washington. His office oversaw a large amount of urgent and top-secret communications between the United States and London. Philby was also responsible for liaising with the CIA and promoting "more aggressive Anglo-American intelligence operations".[41] A leading figure within the CIA was Philby's wary former colleague, James Jesus Angleton, with whom he once again found himself working closely. Angleton remained suspicious of Philby, but lunched with him every week in Washington.

However, a more serious threat to Philby's position had come to light. During the summer of 1945, a Soviet cipher clerk had reused a one time pad to transmit intelligence traffic. This mistake made it possible to break the normally impregnable code. Contained in the traffic (intercepted and decrypted as part of the Venona project) was information that documents had been sent to Moscow from the British Embassy in Washington. The intercepted messages revealed that the British Embassy source (identified as "Homer") travelled to New York City to meet his Soviet contact twice a week. Philby had been briefed on the situation shortly before reaching Washington in 1949; it was clear to Philby that the agent was Donald Maclean, who worked in the British Embassy at the time and whose wife, Melinda, lived in New York. Philby had to help discover the identity of "Homer", but also wished to protect Maclean.[42]

In January 1950, on evidence provided by the Venona intercepts, Soviet atomic spy Klaus Fuchs was arrested. His arrest led to others: Harry Gold, a courier with whom Fuchs had worked, David Greenglass, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The investigation into the British Embassy leak was still ongoing, and the stress of it was exacerbated by the arrival in Washington, in October 1950, of Guy Burgess – Philby's unstable and dangerously alcoholic fellow Soviet spy.[43]

Burgess, who had been given a post as Second Secretary at the British Embassy, took up residence in the Philby family home and rapidly set about causing offence to all and sundry. Aileen Philby resented him and disliked his presence; Americans were offended by his "natural superciliousness" and "utter contempt for the whole pyramid of values, attitudes, and courtesies of the American way of life".[43] J. Edgar Hoover complained that Burgess used British Embassy automobiles to avoid arrest when he cruised Washington in pursuit of homosexual encounters.[43] His dissolution had a troubling effect on Philby; the morning after a particularly disastrous and drunken party, a guest returning to collect his car heard voices upstairs and found "Kim and Guy in the bedroom drinking champagne. They had already been down to the Embassy but being unable to work had come back."[44]

Burgess's presence was problematic for Philby, yet it was potentially dangerous for Philby to leave him unsupervised. The situation in Washington was tense. From April 1950, Maclean had been the prime suspect in the investigation into the Embassy leak.[45] Philby had undertaken to devise an escape plan which would warn Maclean, currently in England, of the intense suspicion he was under and arrange for him to flee. Burgess had to get to London to warn Maclean, who was under surveillance. In early May 1951, Burgess got three speeding tickets in a single day – then pleaded diplomatic immunity, causing an official complaint to be made to the British Ambassador.[46] Burgess was sent back to England, where he met Maclean in his London club.[citation needed]

The SIS planned to interrogate Maclean on 28 May 1951. On 23 May, concerned that Maclean had not yet fled, Philby wired Burgess, ostensibly about his Lincoln convertible abandoned in the Embassy car park. "If he did not act at once it would be too late," the telegram read, "because [Philby] would send his car to the scrap heap. There was nothing more [he] could do."[47] On 25 May, Burgess drove Maclean from his home at Tatsfield, Surrey to Southampton, where both boarded the steamship Falaise to France and then proceeded to Moscow.[48][49]

LondonBurgess had intended to aid Maclean in his escape, not accompany him in it. The "affair of the missing diplomats," as it was referred to before Burgess and Maclean surfaced in Moscow,[50] attracted a great deal of public attention, and Burgess's disappearance, which identified him as complicit in Maclean's espionage, deeply compromised Philby's position. Under a cloud of suspicion raised by his highly visible and intimate association with Burgess, Philby returned to London. There, he underwent MI5 interrogation aimed at ascertaining whether he had acted as a "third man" in Burgess and Maclean's spy ring. In July 1951, he resigned from MI6, preempting his all-but-inevitable dismissal.[51]

Even after Philby's departure from MI6, speculation regarding his possible Soviet affiliations continued. Interrogated repeatedly regarding his intelligence work and his connection with Burgess, he continued to deny that he had acted as a Soviet agent. From 1952, Philby struggled to find work as a journalist, eventually – in August 1954 – accepting a position with a diplomatic newsletter called the Fleet Street Letter.[52] Lacking access to material of value and out of touch with Soviet intelligence, he all but ceased to operate as a Soviet agent.

On 7 November 1955, Philby was officially cleared by Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan, who told the House of Commons, "I have no reason to conclude that Mr. Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of his country, or to identify him with the so-called 'Third Man', if indeed there was one."[53][54] Following this, Philby gave a press conference in which – calmly, confidently, and without the stammer he had struggled with since childhood – he reiterated his innocence, declaring, "I have never been a communist."[55]

Later life and defection

BeirutAfter being exonerated, Philby was no longer employed by MI6 and Soviet intelligence lost all contact with him. In August 1956 he was sent to Beirut as a Middle East correspondent for The Observer and The Economist.[50][56] There, his journalism served as cover for renewed work for MI6.[57]

In Lebanon, Philby at first lived in Mahalla Jamil, his father's large household located in the village of Ajaltoun, just outside Beirut.[57] Following the departure of his father and stepbrothers for Saudi Arabia, Philby continued to live alone in Ajaltoun, but took a flat in Beirut after beginning an affair with Eleanor, the Seattle-born wife of New York Times correspondent Sam Pope Brewer. Following Aileen Philby's death in 1957 and Eleanor's subsequent divorce from Brewer, Philby and Eleanor were married in London in 1959 and set up house together in Beirut.[58] From 1960, Philby's formerly marginal work as a journalist became more substantial and he frequently travelled throughout the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait and Yemen.[59]

In 1961, Anatoliy Golitsyn, a major in the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, defected to the United States from his diplomatic post in Helsinki. Golitsyn offered the CIA revelations of Soviet agents within American and British intelligence services. Following his debriefing in the US, Golitsyn was sent to SIS for further questioning. The head of MI6, Dick White, only recently transferred from MI5, had suspected Philby as the "third man".[57] Golitsyn proceeded to confirm White's suspicions about Philby's role.[60] Nicholas Elliott, an MI6 officer recently stationed in Beirut who was a friend of Philby's and had previously believed in his innocence, was tasked with attempting to secure Philby's full confession.[56]

It is unclear whether Philby had been alerted, but Eleanor noted that as 1962 wore on, expressions of tension in his life "became worse and were reflected in bouts of deep depression and drinking".[61] She recalled returning home to Beirut from a sight-seeing trip in Jordan to find Philby "hopelessly drunk and incoherent with grief on the terrace of the flat," mourning the death of a little pet fox which had fallen from the balcony.[62] When Nicholas Elliott met Philby in late 1962, the first time since Golitsyn's defection, he found Philby too drunk to stand and with a bandaged head; he had fallen repeatedly and cracked his skull on a bathroom radiator, requiring stitches.[63]

Philby told Elliott that he was "half expecting" to see him. Elliott confronted him, saying, "I once looked up to you, Kim. My God, how I despise you now. I hope you've enough decency left to understand why."[64] Prompted by Elliott's accusations, Philby confirmed the charges of espionage and described his intelligence activities on behalf of the Soviets. However, when Elliott asked him to sign a written statement, he hesitated and requested a delay in the interrogation.[57] Another meeting was scheduled to take place in the last week of January. It has since been suggested that the whole confrontation with Elliott had been a charade to convince the KGB that Philby had to be brought back to Moscow, where he could serve as a British penetration agent of Moscow Centre.[3]

On the evening of 23 January 1963, Philby vanished from Beirut, failing to meet his wife for a dinner party at the home of Glencairn Balfour Paul, First Secretary at the British Embassy.[65] The Dolmatova, a Soviet freighter bound for Odessa, had left Beirut that morning so abruptly that cargo was left scattered over the docks;[57] Philby claimed that he left Beirut on board this ship.[66] However, others maintain that he escaped through Syria, overland to Soviet Armenia and thence to Russia.[67]

It was not until 1 July 1963 that Philby's flight to Moscow was officially confirmed.[68] On 30 July Soviet officials announced that they had granted him political asylum in the USSR, along with Soviet citizenship.[69] When the news broke, MI6 came under criticism for failing to anticipate and block Philby's defection, though Elliott was to claim he could not have prevented Philby's flight. Journalist Ben Macintyre, author of several works on espionage, wrote in his 2014 book on Philby that MI6 might have left open the opportunity for Philby to flee to Moscow to avoid an embarrassing public trial. Philby himself thought this might have been the case, according to Macintyre.[70]

When FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was informed that one of MI6's top men was a spy for the Russians, he said, "Tell 'em Jesus Christ only had twelve, and one of them was a double [agent]."[71]

MoscowUpon his arrival in Moscow, Philby discovered that he was not a colonel in the KGB, as he had been led to believe. He was paid 500 rubles a month and his family was not immediately able to join him in exile.[72] It was ten years before he visited KGB headquarters and he was given little real work. Philby was under virtual house arrest, guarded, with all visitors screened by the KGB. Mikhail Lyubimov, his closest KGB contact, explained that this was to guard his safety, but later admitted that the real reason was the KGB's fear that Philby would return to London.[3]

Philby occupied himself by writing his memoirs, published in the UK in 1968 under the title My Silent War, not published in the Soviet Union until 1980.[73] He continued to read The Times, which was not generally available in the USSR, listened to the BBC World Service, and was an avid follower of cricket.

Philby's award of the OBE was cancelled and annulled in 1965.[74] Though Philby claimed publicly in January 1988 that he did not regret his decisions and that he missed nothing about England except some friends, Colman's mustard, and Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce;[75] his wife Rufina Ivanovna Pukhova later described Philby as "disappointed in many ways" by what he found in Moscow. "He saw people suffering too much," but he consoled himself by arguing that "the ideals were right but the way they were carried out was wrong. The fault lay with the people in charge."[9] Pukhova said, "he was struck by disappointment, brought to tears. He said, 'Why do old people live so badly here? After all, they won the war.'"[76] Philby drank heavily and suffered from loneliness and depression; according to Rufina, he had attempted suicide by slashing his wrists sometime in the 1960s.[77]

Philby died of heart failure in Moscow in 1988. He was given a hero's funeral, and posthumously awarded numerous medals by the USSR.

Personal life Memorial in Kuntsevo Cemetery, Moscow

Memorial in Kuntsevo Cemetery, MoscowIn February 1934, Philby married Litzi Friedmann, an Austrian communist whom he had met in Vienna. They subsequently moved to Britain; however, as Philby assumed the role of a fascist sympathiser, they separated. Litzi lived in Paris before returning to London for the duration of the war; she ultimately settled in East Germany.[78]

While working as a correspondent in Spain, Philby began an affair with Frances Doble, Lady Lindsay-Hogg, an actress and aristocratic divorcée who was an admirer of Franco and Hitler. They travelled together in Spain through August 1939.[79]

In 1940 he began living with Aileen Furse in London. Their first three children, Josephine, John and Tommy Philby, were born between 1941 and 1944. In 1946, Philby finally arranged a formal divorce from Litzi. He and Aileen were married on 25 September 1946, while Aileen was pregnant with their fourth child, Miranda. Their fifth child, Harry George, was born in 1950.[80] Aileen suffered from psychiatric problems, which grew more severe during the period of poverty and suspicion following the flight of Burgess and Maclean. She lived separately from Philby, settling with their children in Crowborough while he lived first in London and later in Beirut. Weakened by alcoholism and frequent sickness, she died of influenza in December 1957.[81]

In 1956, Philby began an affair with Eleanor Brewer, the wife of The New York Times correspondent Sam Pope Brewer. Following Eleanor's divorce, the couple married[57] in January 1959. After Philby defected to the Soviet Union in 1963, Eleanor visited him in Moscow. In November 1964, after a visit to the United States, she returned, intending to settle permanently. In her absence, Philby had begun an affair with Donald Maclean's wife, Melinda.[57] He and Eleanor divorced and she departed Moscow in May 1965.[82] Melinda left Maclean and briefly lived with Philby in Moscow. In 1968 she returned to Maclean.

In 1971, Philby married Rufina Pukhova, a Russo-Polish woman twenty years his junior, with whom he lived until his death in 1988.[83]

In popular culture

Fiction based on actual events• Philby, Burgess and Maclean, a Granada TV drama written by Ian Curteis in 1977, covers the period of the late 1940s, when British intelligence investigated Maclean until 1955 when the British government cleared Philby because it did not have enough evidence to convict him.

• Philby has a key role in Mike Ripley's short story Gold Sword published in 'John Creasey's Crime Collection 1990' which was chosen as BBC Radio 4's Afternoon Story to mark the 50th anniversary of D-Day on 6 June 1994.

• Cambridge Spies, a 2003 four-part BBC drama, recounts the lives of Philby, Burgess, Blunt and Maclean from their Cambridge days in the 1930s through the defection of Burgess and Maclean in 1951. Philby is played by Toby Stephens.

• German author Barbara Honigmann's Ein Kapitel aus meinem Leben tells the history of Philby's first wife, Litzi, from the perspective of her daughter.[84]

Speculative fiction• One of the earliest appearances of Philby as a character in fiction was in the 1974 Gentleman Traitor by Alan Williams, in which Philby goes back to working for British intelligence in the 1970s.

• In the 1980 British television film Closing Ranks, a false Soviet defector sent to sow confusion and distrust in British intelligence is unmasked and returned to the Soviet Union. In the final scene, it is revealed that the key information was provided by Philby in Moscow, where he is still working for British intelligence.[85]

• In the 1981 Ted Allbeury novel The Other Side of Silence, an elderly Philby arouses suspicion when he states his desire to return to England.[86]

• The 1984 Frederick Forsyth novel The Fourth Protocol features an elderly Philby's involvement in a plot to trigger a nuclear explosion in Britain. In the novel, Philby is a much more influential and connected figure in his Moscow exile than he apparently was in reality.[87]

o In the 1987 adaptation of the novel, also named The Fourth Protocol, Philby is portrayed by Michael Bilton. In contradiction of historical fact, he is executed by the KGB in the opening scene.

• In the 2000 Doctor Who novel Endgame, the Doctor travels to London in 1951 and matches wits with Philby and the rest of the Cambridge Five.[88]

• The Tim Powers novel Declare (2001) is partly based on unexplained aspects of Philby's life, providing a supernatural context for his behaviour.[89]

• The Robert Littell novel The Company (2002) features Philby as a confidant of former CIA Counter-Intelligence chief James Angleton.[90] The book was adapted for the 2007 TNT television three-part series The Company, produced by Ridley Scott, Tony Scott and John Calley; Philby is portrayed by Tom Hollander.

• Philby appears as one of the central antagonists in William F. Buckley Jr.'s 2004 novel Last Call for Blackford Oakes.[86]

• The 2013 Jefferson Flanders novel The North Building explores the role of Philby in passing American military secrets to the Soviets during the Korean War.[91]

• Daniel Silva's 2018 book, The Other Woman is largely based on Philby's life mission

In alternative histories• The 2003 novel Fox at the Front by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson depicts Philby selling secrets to the Soviet Union during the alternate Battle of the Bulge where German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel turns on the Nazis and assists the Allies in capturing all of Berlin. Before he can sell the secret of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union, he is discovered by the British and is killed by members of MI5 who stage his death as a heart attack.

• The 2005 John Birmingham novel Designated Targets features a cameo of Philby, under orders from Moscow to assist Otto Skorzeny's mission to assassinate Winston Churchill.

Fictional characters based on Philby• The 1971 BBC television drama Traitor starred John Le Mesurier as Adrian Harris, a character loosely based on Kim Philby.

• John le Carré depicts a Philby-like upper-class traitor in the 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. The novel has been adapted as a 1979 TV miniseries, a 2011 film, and radio dramatisations in 1988 and 2009. In real life, Philby had ended le Carré's intelligence officer career by betraying his British agent cover to the Russians.[92]

• In the 1977 book The Jigsaw Man by Dorothea Bennett and the 1983 film adaption of it, The Jigsaw Man, "Sir Philip Kimberly" is a former head of the British Secret Service who defected to Russia, who is then given plastic surgery and sent back to Britain on a spy mission.

• Under the cover name of 'Mowgli' Philby appears in Duncan Kyle's World War II thriller Black Camelot published in 1978.

• John Banville's 1997 novel The Untouchable is a fictionalised biography of Blunt that includes a character based on Philby.

• Philby was the inspiration for the character of British intelligence officer Archibald "Arch" Cummings in the 2005 film The Good Shepherd. Cummings is played by Billy Crudup.

• The 2005 film A Different Loyalty is an unattributed account taken from Eleanor Philby's book, Kim Philby: The Spy I Loved. The film recounts Philby's love affair and marriage to Eleanor Brewer during his time in Beirut and his eventual defection to the Soviet Union in late January 1963, though the characters based on Philby and Brewer have different names.

In music• In the song "Philby", from the Top Priority album (1979), Rory Gallagher draws parallels between his life on the road and a spy's in a foreign country. Sample lyrics : "Now ain't it strange that I feel like Philby / There's a stranger in my soul / I'm lost in transit in a lonesome city / I can't come in from the cold."[93]

• The Philby affair is mentioned in the Simple Minds song "Up on the Catwalk" from their sixth studio album Sparkle in the Rain. The lyrics are: "Up on the catwalk, and you dress in waistcoats / And got brillantino, and friends of Kim Philby."[94]

• The song "Angleton", by Russian indie rock band Biting Elbows, focuses largely on Philby's role as a spy from the perspective of James Jesus Angleton.[citation needed]

• The song 'Traitor' by Renegade Soundwave from their album Soundclash mentions "Philby, Burgess and Maclean" with the lyrics "snitch, grass, informer, you're a traitor; you can't be trusted and left alone".[95]

• The song "Kim Philby", from the self-titled album by Vancouver punk band Terror of Tiny Town (1994) includes the line, "They say he was the third man, but he's number one with us." The lead singer and accordionist of the now defunct band was political satirist Geoff Berner.

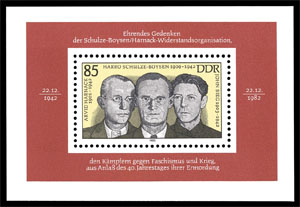

Other• The 1993 Joseph Brodsky essay Collector's Item (published in his 1995 book On Grief and Reason) contains a conjectured description of Philby's career, as well as speculations into his motivations and general thoughts on espionage and politics. The title of the essay refers to a postal stamp commemorating Philby issued in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s.

See also• United Kingdom portal

• Biography portal

• Soviet Union portal

References1. Kim Philby in the Encyclopædia Britannica Online, retrieved 16 November 2009.

2. "The Cambridge Five". International Spy Museum. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

3. Ron Rosenbaum (10 July 1994). "Kim Philby and the Age of Paranoia". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February2008.

4. See The Philby Conspiracy, Page B et al 1968; Chapter 3, pp 30–39

5. Carré, John Le (2004). Conversations with John Le Carré. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 155. ISBN 9781578066698.

6. Treason in the Blood: H. St. John Philby, Kim Philby, and the Spy Case of the Century, by Anthony Cave Brown, Little, Brown publishers, Boston 1994.

7. Stephen Koch: Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Muenzenberg and the Seduction of the Intellectuals. Revised Edition. New York: Enigma Books, 2004.

8. Natasha Walter (10 May 2003). "Spies and lovers". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

9. Genrikh Borovik, The Philby Files, 1994, published by Little, Brown & Company Limited, Canada, ISBN 978-0-316-91015-6. Introduction by Phillip Knightley.

10. Lownie 2016, pp. 52–53.

11. Purvis & Hulbert 2016, pp. 47–48.

12. Macintyre 2015, pp. 37–38.

13. Kim Philby, memorandum in Security Service Archives (1963)

14. Macintyre 2015, p. 44.

15. Lownie 2016, p. 54.

16. Seale, Patrick; McConnville, Maureen (1973). Philby: The Long Road to Moscow. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 72–73.

17. "Theodore Maly". Spartacus Educational.

18. Boris Volodarsky: History Today magazine, London, 5 August 2010

19. Cricinfo Player Profile of Ernest Sheepshanks retrieved 27 November 2008

20. Boyle, Andrew (1979). The Fourth Man: The Definitive Account of Kim Philby, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean and Who Recruited Them to Spy for Russia'. New York: The Dial Press/James Wade. pp. 198–199.

21. Andrew, Christopher (2009). The Defence of the Realm : The Authorized History of MI5. London: Allen Lane. pp. 263–272, 343. ISBN 9780713998856.

22. Seale and McConnville, 110–111

23. Holzman 2013, p. 146.

24. Holzman 2013, p. 135.

25. Lownie 2016, pp. 110–11.

26. Seale and McConnville, 128

27. Lownie 2016, p. 113.

28. Lett, Brian (30 September 2016). "SOE's Mastermind: The Authorised Biography of Major General Sir Colin Gubbins KCMG, DSO, MC". Pen and Sword – via Google Books.

29. Seale and McConnville, 129

30. Seale and McConnville, 161-2

31. Seale and McConnville, 164–165

32. Richelson, Jeffrey T. (1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press US. p. 135. ISBN 019511390X.

33. Boyle, 254–255

34. Gordon Corera, Security correspondent (4 April 2016). "Kim Philby, British double agent, reveals all in secret video". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

35. Boyle, 268

36. Seale and McConnville, 180–181

37. London Gazette Issue 37412 published on 28 December 1945. Page 8

38. Seale and McConnville, 187

39. David Smiley, "Albanian Assignment", foreword by Patrick Leigh Fermor – Chatto & Windus – London – 1984 (ISBN 978-0-7011-2869-2)

40. Boyle, 344

41. Seale and McConnville, 201

42. Richelson, Jeffrey (1995). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-19-507391-1.

43. Seale and McConnville, 209

44. Seale and McConnville, 210

45. Boyle, 362

46. Boyle, 365

47. Boyle, 374

48. Lownie 2016, pp. 237–39.

49. Macintyre 2015, pp. 150–51.

50. Harold Evans (20 September 2009). "The Sunday Times and Kim Philby". The Times. London. Retrieved 30 January2011.

51. Hamrick, S.J. Deceiving the Deceivers: Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. pp. 137

52. Seale and McConnville, 224

53. Fisher, John. Burgess and Maclean: A New Look at the Foreign Office Spies. London: Hale, 1977. pp. 193

54. Hansard, 7 November 1955

55. Roger Wilkes (27 October 2001). "The spy who loved his mum". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

56. McCrum, Robert (28 July 2013). "Kim Philby, the Observer connection and the establishment world of spies". The Observer. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

57. Carver, Tom (11 October 2012). "Diary: Philby in Beirut". London Review of Books. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

58. Seale and McConnville, 243

59. Seale and McConnville, 248

60. Boyle, 432

61. Boyle, 434

62. Boyle, 435

63. Boyle, 436

64. Boyle, 437

65. Boyle, 438

66. Boyle, 471

67. Morris Riley Philby: The Hidden Years, 1990, Penzance: United Writers' Publications.

68. "Biography of Kim Philby". National Cold War Exhibition. RAF Museum Cosford. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

69. Boyle, 441

70. Macintyre, Ben (2014). 'A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1408851722.

71. Le Carré, John, The Pigeon Tunnel, Viking Press, 2016, pg. 203

72. Rufina Philby, Mikhail Lyubimov and Hayden Peake. The Private Life of Kim Philby, the Moscow Years. London: St Ermin's: 1999.

73. David Pryce-Jones: October 2004: The New Criterion published by the Foundation for Cultural Review, New York, a nonprofit public foundation as described in Section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code,

74. London Gazette Issue 43735 published on 10 August 1965. Page 1

75. Stephen Erlanger (12 May 1988). "Kim Philby, Double Agent, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

76. Tom Parfitt and Richard Norton-Taylor (30 March 2011). "Spy Kim Philby died disillusioned with communism". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

77. Alessandra Stanley (19 December 1997). "Last Days of Kim Philby: His Russian Widow's Sad Story". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

78. Seale and McConnville, 84

79. Seale and McConnville, 93

80. Seale and McConnville, 173

81. Seale and McConnville, 226

82. Seale and McConnville, 275

83. Philby, Harold Adrian Russell Kim, (1912–1988), spy by Nigel Clive in Dictionary of National Biography online (accessed 11 November 2007)

84. "Lüge möglichst wahrheitsnah". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

85. Burton, Alan, 1962-. Looking-glass wars : spies on British screens since 1960. Wilmington, Delaware. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-62273-290-6. OCLC 1029246581.

86. Rubin, Charlie (17 July 2005). "'Last Call for Blackford Oakes': Cocktails With Philby". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

87. "The Moscow life of Kim Philby". pravda.ru (English). Retrieved 12 February 2011.

88. Endgame : collected comic strips from the pages of Doctor Who magazine. Hickman, Clayton., Barnes, Alan., Gray, Scott (W. Scott). Tunbridge Wells, England: Panini Books. 2005. ISBN 1905239092. OCLC 857786940.

89. "Declare by Tim Powers". HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

90. "A Cold War Mystery: Was the Soviet Mole Kim Philby a Double Agent... or a Triple Agent?". indiebound.org. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

91. "The North Building by Jefferson Flanders". ForeWord Reviews. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

92. George Plimpton (Summer 1997). "John le Carré, The Art of Fiction No. 149". The Paris Review.

93. "Rory Gallagher – Philby Lyrics". Metrolyrics.com. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

94. "Up on the Catwalk Lyrics – Simple Minds". Lyricsfreak.com. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

95. "Traitor - lyrics". karaoke-lyrics.net. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

Further reading• Holzman, Michael (2013). Guy Burgess: Revolutionary in an Old School Tie. New York: Chelmsford Press. ISBN 978-0-615-89509-3.

• Lownie, Andrew (2016). Stalin's Englishman: The Lives of Guy Burgess. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-473-62738-3.

• Macintyre, Ben (2015). A Spy Among Friends: Philby and the Great Betrayal. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-5178-4.

• Purvis, Stewart; Hulbert, Jeff (2016). Guy Burgess: The Spy Who Knew Everyone. London: Biteback Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84954-913-4.

• Colonel David Smiley, "Irregular Regular", Michael Russell – Norwich – 1994 (ISBN 978-0-85955-202-8). Translated in French by Thierry Le Breton, Au coeur de l'action clandestine des commandos au MI6, L'Esprit du Livre Editions, France, 2008 (ISBN 978-2-915960-27-3). With numerous photographs. Memoirs of a SOE and MI6 officer during the Valuable Project.

• Genrikh Borovik, The Philby Files, 1994, published by Little, Brown & Company Limited, Canada, ISBN 0-316-91015-5 . Introduction by Phillip Knightley.

• Phillip Knightley, Philby: KGB Masterspy 2003, published by Andre Deutsch Ltd, London, ISBN 978-0-233-00048-0. 1st American edition has title: The Master Spy: the Story of Kim Philby, ISBN 0394578902

• Phillip Knightley, The Second Oldest Profession: Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century, 1986, published by W.W. Norton & Company, London.

• Kim Philby, My Silent War, published by Macgibbon & Kee Ltd, London, 1968, or Granada Publishing, ISBN 978-0-586-02860-5. Introduction by Graham Greene, well known author who worked with and for Philby in British intelligence services.

• Bruce Page, David Leitch and Phillip Knightley, Philby: The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation, 1968, published by André Deutsch, Ltd., London.

• Michael Smith, The Spying Game, 2003, published by Politico's, London.

• Richard Beeston, Looking For Trouble: The Life and Times of a Foreign Correspondent, 1997, published by Brassey's, London.

• Desmond Bristow, A Game of Moles, 1993, published by Little Brown & Company, London.

• Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives, 2001, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

• Anthony Cave Brown, "C": The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, Spymaster to Winston Churchill, 1987, published by Macmillan, New York.

• John Fisher, Burgess and Maclean, 1977, published by Robert Hale, London.

• S. J. Hamrick, Deceiving the Deceivers, 2004, published by Yale University Press, New Haven.

• Malcolm Muggeridge, The Infernal Grove: Chronicles of Wasted Time: Number 2, 1974, published by William Morrow & Company, New York.

• Barrie Penrose & Simon Freeman, Conspiracy of Silence: The Secret Life of Anthony Blunt, 1986, published by Farrar Straus Giroux, New York.

• Richard C.S. Trahair and Robert Miller, Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations, 2009, published by Enigma Books, New York. ISBN 978-1-929631-75-9

• Nigel West, editor, The Guy Liddell Diaries: Vol. I: 1939–1942, 2005, published by Routledge, London

• Nigel West & Oleg Tsarev, The Crown Jewels: The British Secrets at the Heart of the KGB Archives, 1998, published by Yale University Press, New Haven.

• Bill Bristow, "My Father The Spy" Deceptions of an MI6 Officer. Published by WBML Publishers. 2012.

• Desmond Bristow. With Bill Bristow. "A Game of Moles" The Deceptions of and MI6 Officer. Published 1993 by Little Brown and Warner.

External links• Annotated bibliography of the Philby Affair

• John Philby – Daily Telegraph obituary

• File release: Cold War Cambridge spies Burgess and Maclean, The National Archives, 23 October 2015