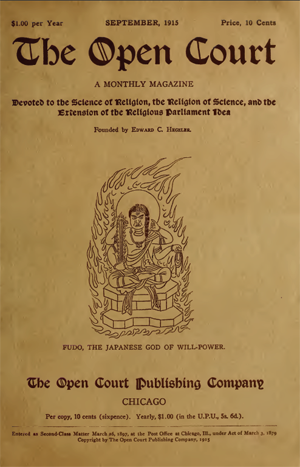

The Open Court: A Monthly Magazine

Founded by Edward C. Hegeler

September, 1915

$1.00 per Year SEPTEMBER, 1915 Price, 10 Cents

The Open Court

A MONTHLY MAGAZINE

Devoted to the Science of Religion, the Religion of Science, and the Extension of the Religious Parliament Idea

Founded by Edward C. Hegeler

VOL. XXIX (No. 9) SEPTEMBER, 1915 NO. 712

FUDO, THE JAPANESE GOD OF WILL-POWER.

CONTENTS:

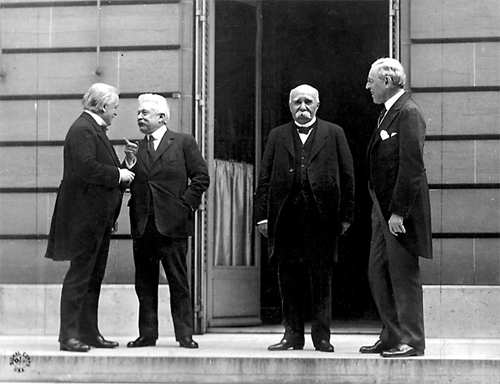

• Frontispiece. Jikokuten, Guardian of the East.

• Fudo-Myowo (Illustrated). Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki 513

• Carlyle and the War. Marshall Kelly 527

• Hyphenation Justified. Paul Carus 557

• A Chronicle of Unparalleled Infamies. An Open Letter to Dr. Paul Carus (With Editorial Reply) 562

• Miss Farmer and Greenacre 572

• Jikokuten, Guardian of the East (With Illustration) 572

• The Lotus Gospel 574

• Book Reviews and Notes 575

The Fragments of Empedocles

By WILLIAM ELLERY LEONARD

A reconstruction of Empedocles's system of creation. Greek-English text. "There is no real creation or annihilation in the universal round of things. There is only the Everlasting Law." Cloth, $1.00

Aesop and Hyssop

By WILLIAM ELLERY LEONARD

Fables adapted and original, in a variety of verse forms, picturesque, lively, and humorous in phrasing, with a moral, fresh in wisdom and succinct in expression, pleasingly appended to each. Profitable for amusement and doctrine in nursery and study. Cloth, $1.50

The Open Court Publishing: Company

Chicago, Illinois

JIKOKUTEN, GUARDIAN OF THE EAST. From a terra cotta in the Todaji temple at Nara (8th century).

FUDO-MYOWO.

BY DAISETZ TEITARO SUZUKI.

FROM the earliest days of Buddhism in Japan, one of the most popular gods is found to be Fudo, whose Sanskrit name is Achala, the Immovable. His name and his general features and attitude suggest the fierceness of his original character. One might think that such a terrible-looking god could represent only evil, destroying every vestige of goodness in the world. But in fact he is worshiped as one who will grant his devotees all the worldly advantages that they may ask of him. Hence his extreme popularity.

The service, which is done by the priest who represents the saint Padma-sambhava, is here summarized. It is called "The Expelling Oblation of the hidden Fierce Ones"...Hum! Through the blessing of the blood-drinking Fierce One, let the injuring demons and evil spirits be kept at bay. I pierce their hearts with this hook; I bind their hands with this snare of rope; I bind their body with this powerful chain; I keep them down with this tinkling bell. Now, O! blood-drinking Angry One, take your sublime seat upon them. Vajor-Agu-cha-dsa! vajora-pasha-hum! vajora-spo-da- va! vajora-ghan-dhi-ho!"

Then chant the following for destroying the evil spirits: —

"Salutation to Heruka, the owner of the noble Fierce Ones! The evil spirits have tricked you and have tried to injure Buddha's doctrine, so extinguish them .... Tear out the hearts of the injuring evil spirits and utterly exterminate them."

Then the supposed corpse of the linka should be dipped in Rakta (blood), and the following should be chanted: —

"Hum! O! ye hosts of gods of the magic-circle! Open your mouths as wide as the earth and sky, clench your fangs like rocky mountains, and prepare to eat up the entire bones, blood, and the entrails of all the injuring evil spirits. Ma-ha mam-sa-la kha hi! Ma-ha tsitta-kha hi! maha-rakta kha-hi! maha-go ro-tsa-na-kha-hi! Maha-bah su-ta kha hi! Maha-keng-ni ri ti kha hi!"

Then chant the following for upsetting the evil spirits...

"Bhyo! Bhyo! On the angry enemies! On the injuring demon spirits! On the voracious demons! turn them all to ashes!

"Mah-ra-ya-rbad bhyo! Upset them all! Upset! Upset!...

A burnt sacrifice is now made by the Demon-king. He pours oil into a cauldron, under which a fire is lit, and when the oil is boiling, he ties to the end of a stick which he holds an image of a man made of paper, and he puts into the boiling oil a skull filled with a mixture of arak (rum), poison, and blood, and into this he puts the image; and when the image bursts into flame, he declares that all the injuries have been consumed...

And when the image is abandoned the crowd tear it to pieces and eagerly fight for the fragments, which are treasured as charms...

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

According to the Shingon sect, he is the central figure of the five Vidyarajas (lords of magic1) or Krodharajas (gods of wrath), and is considered a manifestation of Vairochana Buddha himself (Dainichi2). His original vow, that is, his samaya, (every supernatural being is supposed to have made some kind of vow in the beginning of his existence,) was to remove all possible obstacles which lie in the way of Buddhism.

AN IMAGE OF DAINICHI (VAIROCHANA). The Buddha is here attended by Fudo (Achala) and Kwannon (Avalokiteshvara). From the Shimpuku-ji, Kyoto.

In one of the kalpas3 concerning the worship of this god, we are told how to represent him in a picture: "Paint Achala the Messenger4 on good silk,5 put on him a red garment worn across the body, and his skirt too should be red. One braid of his hair hangs down over his left ear. He looks somewhat squintingly with his left eye. A rope is in his left hand, and a sword is held upright in his right. The top of the sword resembles a lotus-flower, and on its handle there is a jeweled decoration.6 He sits on a rock made of precious stones. His eyebrows are lifted, and his eyes expressing anger are such as to frighten all sentient beings. The color of his body is red and yellow. When you have thus painted the god, take the picture to the bank of a river or to the seashore,7 where he should be enshrined according to the established formula."8

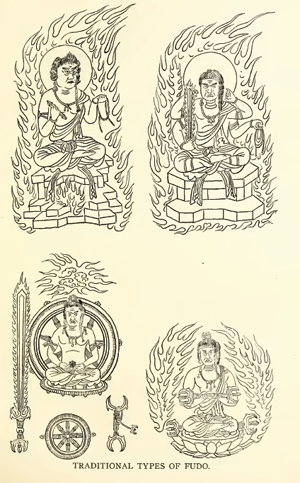

This is the way Fudo is generally painted, and in most modern pictures or images of him we see flames enveloping his whole body, which is blue; and the seat on which he sits or stands is not always decorated with gems; it may be merely a huge block of stone, or a sort of tiled pedestal. His forehead has in most cases some wrinkles in the form of waves, which is in accord with the description in the "Vairochana Sutra."

The meaning of all these various symbols is explained as follows in the introductory part of the Trisatnaya-achala-kalpa (the three-volume version): "There is a deep significance in his being one-eyed," for this is the symbol of the utmost ugliness, and compels Achala to think of his own shortcomings and defects which stand in such contrast to the noble, perfect and superior features of the Buddha. Furthermore, this ugliness tends to frighten away evil beings. The seven knots on the top of his head signify the seven branches of bodhi, wisdom. One braid of hair hanging down his left shoulder typifies his merciful heart, which is sensitive to the sufferings of all lowly and much-neglected beings. . . .The sword in his right hand is meant to wage war against evils in the same way as a worldly warrior fights against his enemy. The rope in his left is to bind those devils whose unruly spirits have to be kept under control by the Buddha's restraining hands. The rock on which he sits is the symbol of his character, that is, immovability. Like the mountain pacifying the tumultuous waves of the great ocean, the rock represents the eternal calmness of the mind. It also represents spiritual treasure as the mine conceals in its bosom precious metals and stones. The fire enveloping the deity signifies the burning up of all the impurities that are attached to the human heart."

FUDO IMAGE AT KOYASAN. Koyasan is the sacred place of the Shingon sect.

Another interpretation of Fudo appears in I-Hsing's "Commentary on the Vairochana Sutra" (Vol. V, pp. 46f.): "This god has in a long past attained his Buddhahood upon the lotus pedestal of Vairochana; but owing to his original vow he now manifests himself in his early imperfect form, which he had at the time of the first awakening of his great heart. Becoming the Tathagata's servant and messenger, he is engaged in various menial works. He holds a sharp sword and a rope in his hands in obedience to the Tathagata's wrathful commands to destroy all sentient beings.11 The rope represents the four practical methods of preaching, woven out of the heart of knowledge [bodhichitta]. The rope will ensnare unruly ones and keep them in check. The sharp sword of wisdom is to cut off the interminable life of karma possessed by unruly spirits, in order to let them obtain a great transcendental existence. When karma's seed of life is removed, all idle windy talk will come to a final end. Therefore the god tightly closes his mouth. The reason why he sees with one eye only, is to show that when the Tathagata looks about with his eye of sameness12 there is not a sentient being who is to be forgiven. Therefore, in whatever work this god is concerned, his whole object is to accomplish this. His firm position on the pile of huge stones signifies the immovable spirit with which he works for the confirmation of the pure heart of knowledge."

Fudo in fact is the incarnation of obedience, faithfulness, and loyalty. He becomes the messenger of Vairochana, for he wishes to perform for him the servile duties of transmitting the august orders and messages of his lordship. As he is commanded, he goes among the poor as well as the noble; he makes no discrimination, and his only anxiety is to execute all the offices, whether good or bad, entrusted to him by Vairochana. He therefore symbolizes all the good virtues of a slave. The knots of hair hanging on the left side of his head denote the number of generations of the master whom he has served. The lotus-flower on his head13 is the vehicle on which he will convey his master to the other shore of life eternal, that is, to the Pure Land. In his menial capacity he will most faithfully serve his worshipers who are at the same time his masters. I am told that the reason his left eye looks in a different direction from the right, is because this is a noticeable peculiarity among the servile class.

In the Trisamaya-achala-kalpa (one-volume version), we are adviced to "make an offering to this holy one with a part of our own food and drink. As his original vow is to give himself up to lovingkindness, he is willing to serve all those who hold and recite his mantrams,14 his desire is to enslave himself, as we may see from his one-eyed form. He accepts our left-off food and if we thus remember him at each meal will be sure to protect us against the evil demons including Vinayaka (Ganesha) and will remove for us whatever obstacles or difficulties we may be encountering."

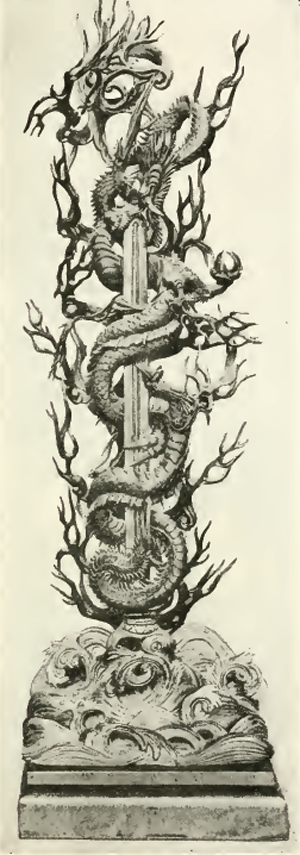

SYMBOLICAL REPRESENTATION OF FUDO. From a figure in the Musee Guimet.

The following story is told of Fudo in I-Hsing's "Commentary on the Vairochana Sutra" (Vol. IX; Chap. 3, "On the Removal of Obstacles"): When the Tathagata received enlightenment all the sentient beings in the universe came to greet him, except the great lord of the heavens, Maheshvara, who was too proud to come and salute the Buddha. Thereupon, Achala was despatched to summon him to earth. But the lord of the heavens surrounded himself, though quite unbecoming to his dignity, with all sorts of filthy things so that nobody would dare approach him; for, however proficient one may be in magic arts, filth is supposed to be the most efficient means of disenchantment. Achala was not to be disheartened. All the filth was immediately devoured and disposed of. Seven times the lord refused to listen to the protest of Achala, saying that he was the supreme master of the heavens and had no cause to yield to any one's request. But the divine messenger proved to be more than a match for the haughty lord; for he firmly set his left foot upon the half-moon on the forehead of the lord himself, while his right foot was placed on that of the noble consort. Both expired under the pressure, but in the meantime they realized the significance of the holy doctrine as disclosed by the Buddha, and were promised their future attainment of Buddhahood. This explains the meaning of certain pictures of Fudo in which he is depicted as stamping on two figures, male and female. Fudo is commonly found attended by two figures and less frequently by eight; but his attendants are said sometimes to be as many as thirty-six or forty-eight. When there are two attendants, the one standing on his left, a young boy, is called Kinkara, and the other to the right who looks like a malicious demon is Chetaka. According to the "Mystic Rites concerning the Eight Boy-Attendants to the Holy Lord of the Immovable," Kinkara is a boy of about fifteen years and wears a lotus crown. His body is white. His hands are folded together and between the forefingers and the thumbs he holds a vajra15 crosswise. He wears a celestial garment as well as a Buddhist robe. The other boy, Chetaka, is of a red lotus color, and his hair is tied in five knots. In his left hand there is a vajra and in his right a vajra staff. As he cherishes anger and evil thoughts, he does not wear a Buddhist robe but a celestial garment only which hangs about his neck and shoulders. But in most of the popular pictures Kinkara holds a lotus-flower. He embodies wisdom whereas Chetaka means bliss.

Fudo sometimes is represented in the form of a sword around which is entwined a dragon or serpent holding the triangular point of the sword in its mouth. This is known as Kurikara Fudo and is supposed to be the symbolical representation of the god. But there is apparently a confusion here, for Kurikara, who is a king of the Nagas or dragons and who seems to be identical with the Sanskrit Kalika, is one of the eight attendants and is probably to be identified with Anavadapta.

There are many variations of Fudo partly because various legends are connected with his life, and partly because the artist or worshiper is free to have a figure of the god as he has conceived him in vision or otherwise. Still another cause of variation, and a strong one, is his extreme popularity.

TRADITIONAL TYPES OF FUDO.

This god is associated with the waterfall, and his image is generally carved in a rock near one. The devotee bathes himself in the flowing water as a token of purification, while devoutly offering his prayers to the flame-enveloped deity. In Tokyo there are many Buddhist temples dedicated to Fudo, and one of the most famous is that at Fukagawa on the south side of the river Sumida. In the midst of the cold season, many earnest followers of the god, men and women, can be seen bathing in the waterfalls which have been artificially constructed there for the purpose. Prayers thus offered during the cold season are considered to be especially efficacious. In former days, all these bathers were naked, but the authorities do not permit this now.

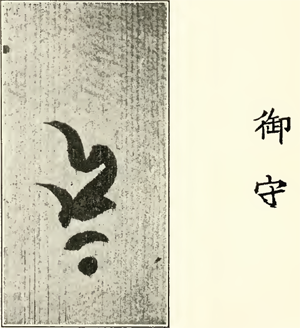

Almost all the temples in Japan issue what is known as an ofuda, "an honorable tablet" or slip, or omamori, "an honorable guard," of various kinds. This is generally a piece of paper (or sometimes a wooden board), oblong and varying in size, ordinarily from about 1x3 to about 7x15 inches, on which is printed the image of a Buddha, a Bodhisattva or one of the gods, but frequently merely a Sanskrit character or phrase, or some words of prayer which have been offered on behalf of the devotee. This omamori is supposed to have the power to ward off evil spirits if a man carries it about him or pastes it up on the entrance door of his residence or on the wall. Some omamoris or ofudas will even keep burglars away from one's house; some will protect the silkworm from an epidemic, while others may insure the safe delivery of a child. These are only a few of the things promised by the Buddhist gods or rather by the priest. Some sample Ofudas are reproduced here, they have come from the Fudo temples.

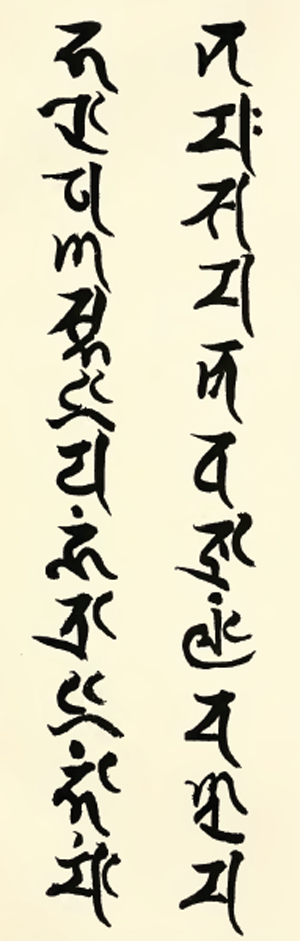

[T]he commonest use of sacred symbols is as talismans to ward off the evils of those malignant planets and demons who cause disease and disaster, as well as for inflicting harm on one's enemy. The symbols here are used in a mystical and magic sense as spells and as fetishes, and usually consist of formulas in corrupt and often unintelligible Sanskrit, extracted from the Mahayana and Tantrik scriptures, and called dharani, as they are believed to "hold" divine powers, and are also used as incantations...

The eating of the paper on which a charm has been written is an ordinary way of curing disease, as indeed it had been in Europe till not so many centuries ago, for the mystic Rx heading our prescriptions is generally admitted to have had its origin in the symbol of Saturn, whom it invoked, and the paper on which the symbol and several other mystic signs were inscribed constituted the medicine, and was itself actually eaten by the patient. The spells which the Lamas use in this way as medicine are shown in the annexed print, and are called "the edible letters" (za-yig).

A still more mystical way of applying these remedies is by the washings of the reflection of the writing in a mirror, a practice not without its parallels in other quarters of the globe. Thus to cure the evil eye as shown by symptoms of mind-wandering and dementia condition — called "byad-'grol" — it is ordered as follows: Write with Chinese ink on a piece of wood the particular letters and smear the writing over with myrobalams and saffron as varnish, and every twenty-nine days reflect this inscribed wood in a mirror, and during reflection wash the face of the mirror with beer, and collect a cupful of such beer and drink it in nine sips.

But most of the charms are worn on the person as amulets. Every individual always wears around the neck one or more of these amulets, which are folded up into little cloth-covered packets, bound with coloured threads in a geometrical pattern. Others are kept in small metallic cases of brass, silver, or gold, set with turquoise stones as amulets, and called "Ga-u." These amulets are fastened to the girdle or sash, and the smaller ones are worn as lockets, and with each are put relics of holy men — a few threads or fragments of cast-off robes of saints or idols, peacock feathers, sacred Kusa grass, and occasionally images and holy pills. Other large charms are affixed overhead in the house or tent to ward off lightning, hail, etc., and for cattle special charms are chanted, or sometimes pasted on the walls of the stalls, etc.

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

The general masses of people nowadays do not understand the full significance of Fudo worship. They go to his temple merely because he is a Buddhist god and as such is naively supposed to grant them anything they may be in need of. For instance, they may pray to him for success in races and games, or good fortune in their commercial enterprises (especially when much risk is involved, or to be free from accidents in travel. But, judging from the general tendency of his character, he seems to be especially efficient in removing all kinds of obstacles which lie in the way of one's undertaking, religious or otherwise. His qualification is more negative than positive. This is natural, for the very fact that a supreme, perfect being had to incarnate himself in this fierce, abnormal, disquieting form proves the extraordinary character of the god. His other title is "the great destroyer of hindrances."

A FUDO OMAMORI. The original was issued by a Fudo temple in Tokyo. The stamp on the top of the picture shows that it has been properly consecrated by the priest.

AN OMAMORI ISSUED BY THE SHINSHO-JI, NARITA. The original is a small piece of wood. The character reads ham, one of the symbolical letters for Fudo. The separate Chinese characters were on the paper cover and signify omamori.

When the worshiper has thoroughly succeeded in identifying himself with the god, we are told, his fire will consume all the worlds and make them one mass of flame shining like seven suns; his mouth will devour like that of the great horse the multiplicity of things; and not the least chance will be left for any evil spirit to work mischief. Thus, he is to be invoked particularly when there are difficulties or obstructions to overcome; for instance, when an epidemic is to be checked, or a drought to be broken, or a personal enemy to be destroyed, or an opposing army to be annihilated, or a building to be insured against fire, storm, earthquake, etc. For the latter case, however, there is a specific ritual to be performed in which Fudo appears in a somewhat different form from the popular one.

OFUDA FROM THE KYOSHININ, A FUDO TEMPLE IN TOKYO.

INSCRIPTION ON COVER. (Reduced.)

In conclusion I will give here three mantrams used in the invocation of Fudo, the Immovable: the short, medium, and unabridged. The short one is: "Namah samantavajranam"; the medium one: "Namah samantavajranam chanda-maharoshana-svataya hum trat ham mam"; and the longest one: "Namah sarva-tatha-gatebhyo vishvamuphebhyah sarvata trat chanda-maharoshana kam khadi khadi sarvavighnam hum trat ham mam." They have no special meaning.

The one we reproduce is the "medium" form written in the siddham style (Japanese, sittan). The Japanese way of reading it is: Nomaku samanda bazara dan senda makaroshada sabataya un tarata kan mam. The cover reads, "The daily-burning-ceremony tablet, Kyoshin-in, Migawari-san." Fudo is sometimes represented by the characters ham-mam or ham alone. His ofuda is often found to be nothing but this character written in the style known as siddham.

_______________

Notes:

1 Ordinarily, five or eight Vidyarajas are mentioned, though there are some more belonging to this class of gods. The five most commonly grouped are Yamantaka (Dai-itok), Trailokyavijaya (Gosanze), Achala (Fudo), Vajrayaksha (Kongo-yasha), and Kundali (Gundari). They all seem to represent Shiva in his destructive form. Theoretically speaking, every Buddha or Bodhisattva has his Krodhakaya, his angry expression, as well as his female counterpart; but the number of the known gods of wrath is less than that of the Buddhas.

About the end of the sixth century A.D., Tantrism or Sivaic mysticism, with its worship of female energies, spouses of the Hindu god Siva, began to tinge both Buddhism and Hinduism. Consorts were allotted to the several Celestial Bodhisats and most of the other gods and demons, and most of them were given forms wild and terrible, and often monstrous, according to the supposed moods of each divinity at different times. And as these goddesses and fiendesses were bestowers of supernatural power, and were especially malignant, they were especially worshipped...

Such was the distorted form of Buddhism introduced into Tibet about 640 A.D.; and during the three or four succeeding centuries Indian Buddhism became still more debased. Its mysticism became a silly mummery of unmeaning jargon and "magic circles," dignified by the title of Mantrayana or "The Spell-Vehicle".

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

2 Dainichi, the great illuminator of the universe, is, according to the Shingon, the central figure of the world-system. It is through him that all existence is made possible, and that life can be enjoyed in its purity though filled with various defilements. That Fudo came to play such an important role in the pantheon of Buddhism is probably due to the fact of his being an incarnation of this all-powerful godhead, Vairochana. But some sutras consider him a manifestation of another Buddha.

3 Rules of ritual, forming a special class in the body of Buddhist literature. They are known in Japan as Himitsu-Giki, mystic rules of worship.

4 His title is sometimes "messenger," sometimes "lord of magic," but sometimes simply "the honorable." In these may be traced various stages of the historical development of the god.

5 This is not always required. To make the prayer especially efficacious for the suppression of evil doers, the devotee may paint the god with his own blood on cloth taken from a grave. It is sometimes recommended to paint him on any good cloth.

6 In none of his pictures so far I have come across is this observed.

7 Hence his association with waterfalls and springs.

8 This is taken from the book containing the "Mystic Rites of the Dharani of Achala the Messenger." A little further down, however, we have a somewhat different description of the god. He is now to be reddish-yellow, wearing a blue garment across the body, but still with a red skirt. His left-side braid is the color of a black cloud. The features are boyish. A vajra (thunderbolt) is in his right hand and a rope in his left. From both ends of his mouth his tusks are slightly visible. His angry eyes are red. Enveloped in flames he sits on a hill of stone.

In the Trisamaya-achala-kalpa (there are two versions of this book, one in three volumes and the other in one), the god is supposed to wear a skirt of the color of red earth and sits on a lotus-flower. In another place he holds a vajra, not a sword, in his right hand and a sacred staff in his left. The eyes are somewhat reddish, and his whole person is enveloped in flames.

These representations, though differing more or less in detail, are essentially alike. Quite another form of the god is described in the "Book of Rites concerning the Ten Gods of Wrath" as follows: "He has a squinting eye boyish features, six arms and three faces each of which has three eyes, and he wears boyish personal ornaments. The front face is smiling; the right is yellowish, with the tongue sticking out, the color of which is bloody; the left face is white, has an angry expression, uttering the sound "hum." The color of the body is blue; the feet rest on a lotus-flower and on the hill of precious stones. He stands with a dancer's attitude, and has power to keep away all evil ones. The entire person wrapped in flames has a circle of rays about it like the sun. The first right hand has a sword, the second a vajra, the third an arrow. Of the left hands the first holds a rope with the thumb standing, the second the Prajnaparamita Sutra, and the third a bow. The god wears a Buddha crown which is the symbol of Akshobhya Buddha.

There are some other forms of the god, more or less unlike the foregoing ones, but I will not go into details here. Suffice it to state in a general way that he assumes different features according to the different purposes for which his help is invoked. For instance, when he is requested to suppress the enemy, his body is to be painted yellow, with four faces and four arms. Sharp tusks are protruding from the mouth. His expression of anger is most intense, and encircled in burning flames his attitude is such as to make one think that he is going at once to devour an entire army of the enemy.

9 This tallies with the "Rites of the Ten Gods" as well as with Vajrapani's description of the god in his "Sutra on the Baptism of Light."

10 In the foregoing descriptions, squinting; but in some images both eyes look in the same direction.

11 Meaning "every evil tendency to be found in us."

12 In another place this is understood as meaning the uniqueness of the Buddha's spiritual eye-sight which is one, and not two nor three.

13 This lotus-flower is not mentioned anywhere in the kalpas in connection with the worship of this god.

14 Mystical verse.

15 This thunderbolt becomes the magic wand of Tibetan Buddhism.