Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

The Eugenics Society archives in the Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine

by Lesley A Hall

When the Wellcome Trust first set up the Contemporary Medical Archives Centre (now subsumed into Archives and Manuscripts) within the Wellcome Institute Library in 1979, it was with the aim of collecting and preserving records illuminating twentieth century developments in medicine, biomedical science and healthcare. It was clear that a good deal of important material was falling through existing systems of preservation. The initial assumption was that the focus of collecting policy would be the papers of individual scientists and doctors, along the lines already being pursued by the Contemporary Scientists Archive Centre in Oxford (now the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists and relocated to Bath). However, it emerged at an early stage of the CMAC’s activities that there was equal urgency to preserve the archives of voluntary organisations operating within the medical/health/welfare field. These shed an important light on these issues within the British context, given the importance of voluntarism. The Wellcome now holds records of numerous professional bodies, learned societies, research institutions, charities, campaigning organisations and propagandist associations (and bodies which either simultaneously or at different phases of their existence performed several of these functions).

Although the papers of a few organisations had already been placed in the Wellcome Institute prior to the appointment of an archivist, the first organisational archive actively acquired by the newly established CMAC was that of the Eugenics Society, early in 1980. The CMAC has already received an important collection of papers of Dr Marie Stopes which had been rejected by the (then) British Museum Reading Room (now the Department of Manuscripts, British Library), although it had accepted substantial portions of her extremely large archive of personal papers and material relating to the birth control clinics she established. These two accessions laid the foundations for one of the major strengths of our collections, birth control and reproductive health more generally. The Wellcome now holds the most important archive on the birth control movement in the UK.

The Eugenics Society archive has been one of the most popular collections in the Wellcome: files were being made available to researchers even before cataloguing had been fully completed, such was the demand. As an archive it is extremely rich, and is of major interest well beyond research into the internal activities and politics of the Society, and indeed extending beyond the study of eugenics as an intellectual and political phenomenon. Over the past 10 years it has consistently been among both the most heavily-used collections we hold, with an average number of 18 readers per year, and among the collections from which the greatest numbers of items have been produced, with an average of over 500 productions each year. In the light of the latter statistic, the decision was recently taken to make researchers use the microfiche copies of the most heavily used portions of the collection for reasons of conservation. While many users are students undertaking dissertation projects, or individuals looking up one or two files bearing on a tangential subject of research, there have been major studies done, and still currently in progress, making extensive use of this archive. Some international scholars return year after year.

The Society was founded in 1907 with the by then very elderly Sir Francis Galton as President. The record for the early years of the Eugenics Education Society, as it was known until 1926, is relatively sparse compared to what survives for the period after approximately 1920. However, there is a complete run of Annual Reports from 1908, and before 1915, when they became much slimmer for reasons of wartime economy, these are extremely full and detailed and include membership lists (there are a number of irregular discrete membership lists for subsequent years). There are also minutes of Council from 1907, which include those of the Executive Council from 1913. The solid core of minute books continues to the 1960s (later volumes still being retained by the Society). Besides Council, Executive and Finance Committee minutes, increasing numbers of committees were set up from the 1920s for specific purposes (long and short-term), or to study and report on particular issues. These included Film, 1927; Propaganda, 1932-1940; Family Allowances, 1932-1934; Birth Control, 1932-1934; Research, 1923-1931, 1946-1956; and Editorial, 1936-1967.

Figure 1

The wider context within which the Society was established is well-documented in a series of volumes of newspaper cuttings, 1907-1910. These form part of a substantial group of press-cuttings within the collection, in both chronological and subject sequences, up to the 1970s. There are a number of gaps in the coverage, in particular the 1910s and 1920s represent a major lacuna, and there is also relatively little for the 1950s, although two files of cuttings concerning the 1958 debates on artificial insemination contextualise the Society’s own files on the subject and the audiotapes of doctors who were practising it recorded by the AID Investigation Council which it set up.

A very few files survive from the early years, including a substantial number of press-cuttings about the First International Eugenics Conference held in London in 1912, and one file on ‘Feeblemindedness’, which was, of course, an area in which the Society was particularly anxious to influence policy. However, on the whole this early material reflects propaganda activities rather than impact on policy, with items on conferences, notices of lectures, and minutes of the Summer School on Civics and Eugenics.

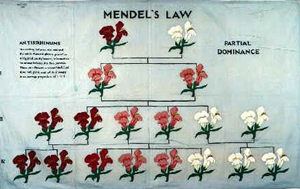

Figure 2

After 1920 an ever-increasing number of files, containing correspondence and other materials, survive. Two main sequences are particularly heavily used as they demonstrate the extraordinarily broad range of the Society’s interests and spheres of contact. There are 22 boxes of correspondence arranged by individual correspondent (‘People’): some of these were members or officers of the Society, but a considerable number were individuals with whom the Society was in contact for various reasons -– liaison on matters of mutual interest, requests to address meetings –- and even members of the general public. These files include many distinguished names, and even a few noted antagonists of eugenics feature, such as Dr Letitia Fairfield, feminist, socialist, Roman Catholic convert, and first female senior medical officer of the London County Council. There are slightly more boxes of ‘General’ files, containing materials either on specific subjects of interest to the Society, or pertaining to their relations with other organisations.

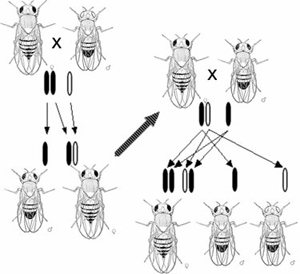

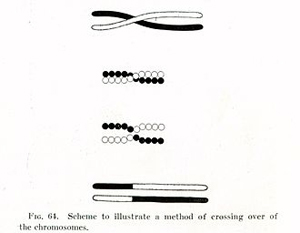

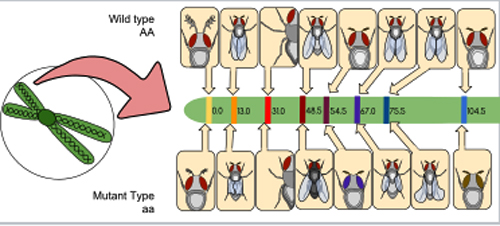

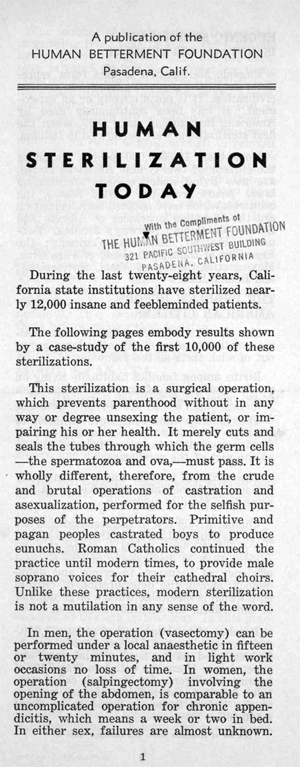

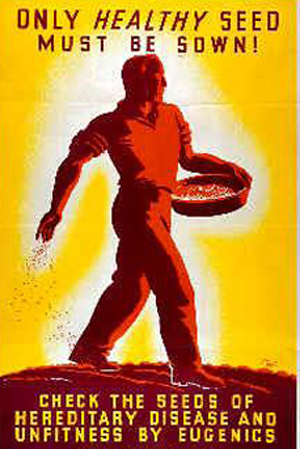

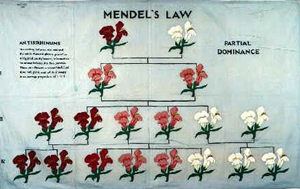

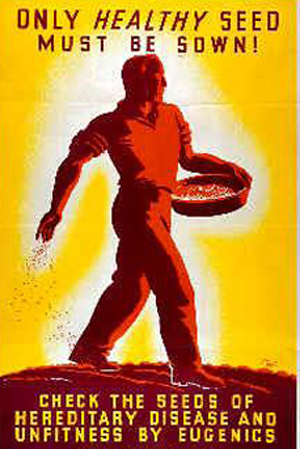

A number of other groups of material are also of considerable research interest. There is a single box of files on Branches and Other Societies, which include both provincial and regional branches and societies in the UK, organisations in other countries, and international bodies. The collection includes some material on family histories and pedigrees. The propaganda activities of the Society from the mid-1920s are well reflected in the archive. Increasing financial stability enabled it to support a small team of lecturers to go about the country addressing meetings of a wide range of organisations, from Women’s Co-operative Guilds to Rotary Clubs, and to take stands at exhibitions, health weeks and conferences. Reports were returned [see Figure 1] and these provide a very useful source about responses from audiences and their preconceptions. There also survive various visual aids prepared for exhibitions and lectures, including charts demonstrating heredity -– there is a particularly attractive one on the antirrhinum [see Figure 2] -– magic lantern slides, and posters. Besides their main purpose these also typify contemporary graphic design [see Figure 3: ‘Healthy Seed]. Two versions of the film made in the 1930s, with narration by Sir Julian Huxley, survive: the longer From Generation to Generation, and the abbreviated Heredity in Man. These are made available for viewing on video subject to the usual conditions of access (see below). Other visual materials include cartoons, a sketch of an armorial achievement deemed appropriate to the Society, the design for the ‘Eugenic family’ extensively used on the Society’s literature during the 1930s [see Figure 4], and some portrait photographs of individuals associated with the Society, including several members of Sir Francis Galton’s own family.

Figure 3

Figure 4

The financial position of the Society was rendered particularly solid by the 1929 bequest from the wealthy and eccentric Australian sheep-farmer Henry Twitchin. The collection includes not only a substantial amount of correspondence between Twitchin and Major Leonard Darwin (when the latter was President of the Society) prior to his death, but material on his family background and on the administration of his estate.

Embedded within this collection are various items originating with specific individuals or organisations who or which were connected with the Society. There are two boxes of papers of Sir Bernard Mallet, President of the Society, 1929-1932, created in his personal rather than his official capacity. On her death in 1958, Marie Stopes left her birth control clinic (and her library) to the Society. The collection therefore includes some clinic administrative material and other correspondence of Stopes’s, presumably found on the premises, as well as the records of the Marie Stopes Memorial Centre set up by the Eugenics Society to administer the clinic.

Because this clinic was not constrained by the various limitations of the Family Planning Association, it was able to do innovative work in the provision of contraception for the unmarried (one is not quite sure whether the late Dr Stopes would have approved of this!). A number of items were given by Dr G. C. Bertram from his own collection of papers accumulated during his years of association with the Society. The Society provided support to the Birth Control Investigation Committee, 1927-1932, and the Joint Committee on Voluntary Sterilisation, 1934-1938, and records of both these bodies can be found in the archive. There is a good deal generally on the campaign to obtain Parliamentary legislation enabling voluntary sterilisation in the early 1930s, including letters from members of the general public trying to obtain this operation in the face of medical indifference or outright refusal, and as already mentioned, the Society took an active part in the debates on artificial insemination by donor in the period after World War II.

Besides the archives of the Society itself, a number of other collections in the Wellcome Library shed light on its activities and fill out the picture. The papers of Carlos Paton Blacker, FRCP, who was General Secretary from 1931 to 1952 and Honorary Secretary 1952-1961, contain correspondence with and about the Society, and also illuminate his less formal contacts with other members and officers of the Society, many of whom were or became personal friends. They also document his wider involvement in the birth control movement, from the Birth Control Investigation Committee in the 1920s, in which he played a leading role, to his work with the Simon Population Trust on vasectomy provision in the 1960s and 70s. After the Second World War Blacker was asked to comment on the ‘experimental work on eugenics performed in concentration camps by the medical profession in Germany’ and his papers include both notes from 1947, and his article ‘"Eugenic" Experiments Conducted by the Nazis on Human Subjects’, published in The Eugenics Review in 1952. The papers of the biologist Sir Alan Parkes also contain some items on the Society. The copious Family Planning Association archives contain material directly dealing with its relationship with the Eugenics Society, including further records of the Birth Control Investigation Committee, as well as correspondence with individuals such as Blacker and Baker, and discussions in committee about relations between the two bodies. The Marie Stopes papers, which consist predominantly of correspondence received from the general public who had read her books or seen her name in the press, include letters asking about questions of ‘breeding’ in the light of family health issues, as well as specifically on birth control. Most of her correspondence with the Society and with C. P. Blacker is to be found among the papers in the British Library Department of Manuscripts. The papers of the long-lived physician Frederick Parkes Weber FRCP (1863-1962) contain items testifying to his personal interest in the topic of eugenics (among the very many subjects in which he was interested), and, due to his particular medical concerns, this collection is actually a better resource for the study of the developing understanding of, and attitudes towards, genetic disorders within the medical profession between c. 1890 and 1960, than the archives of the Eugenics Society itself. Two files of copy correspondence from the Rockefeller Archive Centre, Tarrytown, New York, USA, about Rockefeller funding for research projects of the Society, mainly for John R. Baker’s spermicide research, 1934-1940, are also held.

What we do not have at the Wellcome are the papers of Sir Francis Galton: due to occasional misunderstandings about the relationship between the Galton Institute and this eminent late-nineteenth century polymath we sometimes receive requests for information relating to, e.g., Galton’s meteorological research or criminological investigations. His papers are, in fact, held just across the road in the Library of University College London (as are the papers of his disciple Karl Pearson), and UCL also houses a small museum of Galton artefacts.

The Wellcome Library holds the books and pamphlets formerly in the Eugenics Society Library, transferred in 1988 at the time of the move out of the Eccleston Square offices. These include many associational copies, especially for Marie Stopes, as a result of her bequest to the Society: numerous volumes formerly in her possession have been annotated by her in her dashing and unmistakable handwriting, which adds considerably to their interest. The Library catalogue (which includes the books and pamphlets from the Society Library) can be consulted online at http://www.wellcomelibrary.org.

The Eugenics Society archives are open to researchers by appointment with Archives and Manuscripts, once they have gained the prior permission of the Galton Institute, and completed both an undertaking for the use of archives and manuscripts and a request to see restricted access material, which includes information as to exactly what they wish to see and how they propose to use it. Material is ordered, at present, using the references provided by a word-processed handlist (finding aids are currently being converted into a CALM 2000 database, which will enable them to be made available for searching online), produced by the archivists, and consulted under supervision in the Poynter Room (rare materials reading area) of the Wellcome Library. The archivists are always happy to answer queries (though we do not undertake research) and to provide copies of lists.

Contact details:

Archives and Manuscripts

Research and Special Collections

Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine

183 Euston Road

London NW1 2BE

England UK

Phone 0207-611-8483/8486

Fax 0207-611-8703

Email arch+mss@wellcome.ac.uk

Wellcome Library website: http://www.wellcomelibrary.org

by Lesley A Hall

When the Wellcome Trust first set up the Contemporary Medical Archives Centre (now subsumed into Archives and Manuscripts) within the Wellcome Institute Library in 1979, it was with the aim of collecting and preserving records illuminating twentieth century developments in medicine, biomedical science and healthcare. It was clear that a good deal of important material was falling through existing systems of preservation. The initial assumption was that the focus of collecting policy would be the papers of individual scientists and doctors, along the lines already being pursued by the Contemporary Scientists Archive Centre in Oxford (now the National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists and relocated to Bath). However, it emerged at an early stage of the CMAC’s activities that there was equal urgency to preserve the archives of voluntary organisations operating within the medical/health/welfare field. These shed an important light on these issues within the British context, given the importance of voluntarism. The Wellcome now holds records of numerous professional bodies, learned societies, research institutions, charities, campaigning organisations and propagandist associations (and bodies which either simultaneously or at different phases of their existence performed several of these functions).

Although the papers of a few organisations had already been placed in the Wellcome Institute prior to the appointment of an archivist, the first organisational archive actively acquired by the newly established CMAC was that of the Eugenics Society, early in 1980. The CMAC has already received an important collection of papers of Dr Marie Stopes which had been rejected by the (then) British Museum Reading Room (now the Department of Manuscripts, British Library), although it had accepted substantial portions of her extremely large archive of personal papers and material relating to the birth control clinics she established. These two accessions laid the foundations for one of the major strengths of our collections, birth control and reproductive health more generally. The Wellcome now holds the most important archive on the birth control movement in the UK.

The Eugenics Society archive has been one of the most popular collections in the Wellcome: files were being made available to researchers even before cataloguing had been fully completed, such was the demand. As an archive it is extremely rich, and is of major interest well beyond research into the internal activities and politics of the Society, and indeed extending beyond the study of eugenics as an intellectual and political phenomenon. Over the past 10 years it has consistently been among both the most heavily-used collections we hold, with an average number of 18 readers per year, and among the collections from which the greatest numbers of items have been produced, with an average of over 500 productions each year. In the light of the latter statistic, the decision was recently taken to make researchers use the microfiche copies of the most heavily used portions of the collection for reasons of conservation. While many users are students undertaking dissertation projects, or individuals looking up one or two files bearing on a tangential subject of research, there have been major studies done, and still currently in progress, making extensive use of this archive. Some international scholars return year after year.

The Society was founded in 1907 with the by then very elderly Sir Francis Galton as President. The record for the early years of the Eugenics Education Society, as it was known until 1926, is relatively sparse compared to what survives for the period after approximately 1920. However, there is a complete run of Annual Reports from 1908, and before 1915, when they became much slimmer for reasons of wartime economy, these are extremely full and detailed and include membership lists (there are a number of irregular discrete membership lists for subsequent years). There are also minutes of Council from 1907, which include those of the Executive Council from 1913. The solid core of minute books continues to the 1960s (later volumes still being retained by the Society). Besides Council, Executive and Finance Committee minutes, increasing numbers of committees were set up from the 1920s for specific purposes (long and short-term), or to study and report on particular issues. These included Film, 1927; Propaganda, 1932-1940; Family Allowances, 1932-1934; Birth Control, 1932-1934; Research, 1923-1931, 1946-1956; and Editorial, 1936-1967.

Figure 1

The wider context within which the Society was established is well-documented in a series of volumes of newspaper cuttings, 1907-1910. These form part of a substantial group of press-cuttings within the collection, in both chronological and subject sequences, up to the 1970s. There are a number of gaps in the coverage, in particular the 1910s and 1920s represent a major lacuna, and there is also relatively little for the 1950s, although two files of cuttings concerning the 1958 debates on artificial insemination contextualise the Society’s own files on the subject and the audiotapes of doctors who were practising it recorded by the AID Investigation Council which it set up.

A very few files survive from the early years, including a substantial number of press-cuttings about the First International Eugenics Conference held in London in 1912, and one file on ‘Feeblemindedness’, which was, of course, an area in which the Society was particularly anxious to influence policy. However, on the whole this early material reflects propaganda activities rather than impact on policy, with items on conferences, notices of lectures, and minutes of the Summer School on Civics and Eugenics.

Figure 2

After 1920 an ever-increasing number of files, containing correspondence and other materials, survive. Two main sequences are particularly heavily used as they demonstrate the extraordinarily broad range of the Society’s interests and spheres of contact. There are 22 boxes of correspondence arranged by individual correspondent (‘People’): some of these were members or officers of the Society, but a considerable number were individuals with whom the Society was in contact for various reasons -– liaison on matters of mutual interest, requests to address meetings –- and even members of the general public. These files include many distinguished names, and even a few noted antagonists of eugenics feature, such as Dr Letitia Fairfield, feminist, socialist, Roman Catholic convert, and first female senior medical officer of the London County Council. There are slightly more boxes of ‘General’ files, containing materials either on specific subjects of interest to the Society, or pertaining to their relations with other organisations.

A number of other groups of material are also of considerable research interest. There is a single box of files on Branches and Other Societies, which include both provincial and regional branches and societies in the UK, organisations in other countries, and international bodies. The collection includes some material on family histories and pedigrees. The propaganda activities of the Society from the mid-1920s are well reflected in the archive. Increasing financial stability enabled it to support a small team of lecturers to go about the country addressing meetings of a wide range of organisations, from Women’s Co-operative Guilds to Rotary Clubs, and to take stands at exhibitions, health weeks and conferences. Reports were returned [see Figure 1] and these provide a very useful source about responses from audiences and their preconceptions. There also survive various visual aids prepared for exhibitions and lectures, including charts demonstrating heredity -– there is a particularly attractive one on the antirrhinum [see Figure 2] -– magic lantern slides, and posters. Besides their main purpose these also typify contemporary graphic design [see Figure 3: ‘Healthy Seed]. Two versions of the film made in the 1930s, with narration by Sir Julian Huxley, survive: the longer From Generation to Generation, and the abbreviated Heredity in Man. These are made available for viewing on video subject to the usual conditions of access (see below). Other visual materials include cartoons, a sketch of an armorial achievement deemed appropriate to the Society, the design for the ‘Eugenic family’ extensively used on the Society’s literature during the 1930s [see Figure 4], and some portrait photographs of individuals associated with the Society, including several members of Sir Francis Galton’s own family.

Figure 3

Figure 4

The financial position of the Society was rendered particularly solid by the 1929 bequest from the wealthy and eccentric Australian sheep-farmer Henry Twitchin. The collection includes not only a substantial amount of correspondence between Twitchin and Major Leonard Darwin (when the latter was President of the Society) prior to his death, but material on his family background and on the administration of his estate.

Embedded within this collection are various items originating with specific individuals or organisations who or which were connected with the Society. There are two boxes of papers of Sir Bernard Mallet, President of the Society, 1929-1932, created in his personal rather than his official capacity. On her death in 1958, Marie Stopes left her birth control clinic (and her library) to the Society. The collection therefore includes some clinic administrative material and other correspondence of Stopes’s, presumably found on the premises, as well as the records of the Marie Stopes Memorial Centre set up by the Eugenics Society to administer the clinic.

Because this clinic was not constrained by the various limitations of the Family Planning Association, it was able to do innovative work in the provision of contraception for the unmarried (one is not quite sure whether the late Dr Stopes would have approved of this!). A number of items were given by Dr G. C. Bertram from his own collection of papers accumulated during his years of association with the Society. The Society provided support to the Birth Control Investigation Committee, 1927-1932, and the Joint Committee on Voluntary Sterilisation, 1934-1938, and records of both these bodies can be found in the archive. There is a good deal generally on the campaign to obtain Parliamentary legislation enabling voluntary sterilisation in the early 1930s, including letters from members of the general public trying to obtain this operation in the face of medical indifference or outright refusal, and as already mentioned, the Society took an active part in the debates on artificial insemination by donor in the period after World War II.

Besides the archives of the Society itself, a number of other collections in the Wellcome Library shed light on its activities and fill out the picture. The papers of Carlos Paton Blacker, FRCP, who was General Secretary from 1931 to 1952 and Honorary Secretary 1952-1961, contain correspondence with and about the Society, and also illuminate his less formal contacts with other members and officers of the Society, many of whom were or became personal friends. They also document his wider involvement in the birth control movement, from the Birth Control Investigation Committee in the 1920s, in which he played a leading role, to his work with the Simon Population Trust on vasectomy provision in the 1960s and 70s. After the Second World War Blacker was asked to comment on the ‘experimental work on eugenics performed in concentration camps by the medical profession in Germany’ and his papers include both notes from 1947, and his article ‘"Eugenic" Experiments Conducted by the Nazis on Human Subjects’, published in The Eugenics Review in 1952. The papers of the biologist Sir Alan Parkes also contain some items on the Society. The copious Family Planning Association archives contain material directly dealing with its relationship with the Eugenics Society, including further records of the Birth Control Investigation Committee, as well as correspondence with individuals such as Blacker and Baker, and discussions in committee about relations between the two bodies. The Marie Stopes papers, which consist predominantly of correspondence received from the general public who had read her books or seen her name in the press, include letters asking about questions of ‘breeding’ in the light of family health issues, as well as specifically on birth control. Most of her correspondence with the Society and with C. P. Blacker is to be found among the papers in the British Library Department of Manuscripts. The papers of the long-lived physician Frederick Parkes Weber FRCP (1863-1962) contain items testifying to his personal interest in the topic of eugenics (among the very many subjects in which he was interested), and, due to his particular medical concerns, this collection is actually a better resource for the study of the developing understanding of, and attitudes towards, genetic disorders within the medical profession between c. 1890 and 1960, than the archives of the Eugenics Society itself. Two files of copy correspondence from the Rockefeller Archive Centre, Tarrytown, New York, USA, about Rockefeller funding for research projects of the Society, mainly for John R. Baker’s spermicide research, 1934-1940, are also held.

What we do not have at the Wellcome are the papers of Sir Francis Galton: due to occasional misunderstandings about the relationship between the Galton Institute and this eminent late-nineteenth century polymath we sometimes receive requests for information relating to, e.g., Galton’s meteorological research or criminological investigations. His papers are, in fact, held just across the road in the Library of University College London (as are the papers of his disciple Karl Pearson), and UCL also houses a small museum of Galton artefacts.

The Wellcome Library holds the books and pamphlets formerly in the Eugenics Society Library, transferred in 1988 at the time of the move out of the Eccleston Square offices. These include many associational copies, especially for Marie Stopes, as a result of her bequest to the Society: numerous volumes formerly in her possession have been annotated by her in her dashing and unmistakable handwriting, which adds considerably to their interest. The Library catalogue (which includes the books and pamphlets from the Society Library) can be consulted online at http://www.wellcomelibrary.org.

The Eugenics Society archives are open to researchers by appointment with Archives and Manuscripts, once they have gained the prior permission of the Galton Institute, and completed both an undertaking for the use of archives and manuscripts and a request to see restricted access material, which includes information as to exactly what they wish to see and how they propose to use it. Material is ordered, at present, using the references provided by a word-processed handlist (finding aids are currently being converted into a CALM 2000 database, which will enable them to be made available for searching online), produced by the archivists, and consulted under supervision in the Poynter Room (rare materials reading area) of the Wellcome Library. The archivists are always happy to answer queries (though we do not undertake research) and to provide copies of lists.

Contact details:

Archives and Manuscripts

Research and Special Collections

Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine

183 Euston Road

London NW1 2BE

England UK

Phone 0207-611-8483/8486

Fax 0207-611-8703

Email arch+mss@wellcome.ac.uk

Wellcome Library website: http://www.wellcomelibrary.org