Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Report of the Operations of the Biological Laboratory [The Wauwepex Society]

by H.W. Conn, Ph.D., Commissioners of Fisheries

from Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Issues 35-42, by New York (State) Legislature Assembly

1892

As director of the biological laboratory for the session of 1892, I will present the following report:

The laboratory has been in session for eight weeks, from July sixth to August twenty eighth, as announced in the prospectus. During that time, the following persons have been present as instructors or lecturers:

Board of Instruction.

Professor Herbert W. Conn, Ph.D., Wesleyan University, director of the laboratory.

Professor Charles W. Hargitt, Ph.D., Syracuse University, associate director.

Professor Henry L. Osborn, Ph.D., Hamline University, associate director.

Lecturers.

Professor Henry F. Osborn, Columbia College.

Professor John B. Smith, Rutgers College.

Professor Byron D. Halstead, Rutgers College.

Dr. Thomas Morong, Columbia College, Herbarium.

Professor Franklin W. Hooper, Brooklyn Institute.

Professor Julius Nelson, Rutgers College.

As students in the laboratory, taking the regular courses, there have been present fifteen persons, as follows:

Louis Curtis Ager, student, Long Island Hospital.

E.V. Agramonte, M.D., physician, New York city.

Miss Ida W. Aikman, teacher, Brooklyn.

Miss Martha T. Austin, teacher, Easthampton, Mass.

John T. Barnhart, instructor, Wesleyan University.

Miss Edith M. Brace, student, University of Nebraska.

Miss Lillie C. Brown, teacher, New Britain, Conn.

Duncan S. Johnson, instructor, Wesleyan University.

Franklin T. Kurt, student, Wesleyan University.

James T. O’Connor, M.D., Ph.D., physician, New York city.

Mrs. James T. O’Connor, M.D., clinical professor, New York Medical College and Hospital for Women.

Miss M. Josephine Shepard, teacher, Brooklyn.

Miss Elizabeth M. Sturgis, student, New York city.

William W. Vibbart, student, Trinity College.

Walter S. Watson, student, Wesleyan University.

During the summer the work at the laboratory has been as follows:

First. A course in general zoology. – The outline of this course has been practically the same as that of the course given during the previous year, and has consisted of daily lectures and laboratory excercises. For reasons which were given in my last report, the course of regular class instruction lasted only the first six weeks of the session, the last two weeks being devoted to more independent work on the part of the students upon special subjects of their own choosing. This course in zoology has been given conjointly by the director and the associate directors. Professor Hargitt has conducted the work upon protozoa, coelentera and echinoderma. Professor Osborn has had charge of the work upon molluska and arthropoda, and Professor Conn, the work upon vermes, annelid and vertebrates. Nearly all of the students in the laboratory took the whole of this course.

Second. A course of practical work in bacteriology. – This course has been like that of last year, and has consisted of elementary instruction in bacteriological methods, such as making culture fluids, staining bacteria, etc. No definite instruction has been given, but personal direction to those wishing work along this line.

Third. A course of twelve lectures has been given by Professor Conn upon the history of bacteriology. This course has been a popular course, designed for all persons present at the laboratory, and has given an elementary outline of the history of the development of the study of bacteriology and of all the important facts discovered up to the present time.

Fourth. A large amount of miscellaneous work has been done by different members of the party. It has included staining and mounting microscopic specimens, section cutting, and other work in historical technique, the study of embryology of several types, study of flowers and preparing of herbaria, and a large amount of general zoology and collecting.

Fifth. Original investigations have been undertaken by members of the laboratory staff and by some of the visitors from other colleges. The work has comprised the following subjects: Study of the new species of hydroids; the embryological development of crustacean; systematic study of salt water protozoa; bacteriological study of a disease attacking the trout in the fish hatchery.

Sixth. In addition to the regular work, a number of miscellaneous lectures have been given in the laboratory. These have been as follows:

By Professor F.W. Hooper, “Agassiz at Penakese.”

By Dr. Morong, “Orchidaceae.” Under the guidance of Dr. Morong, three botanical excursions have been taken by those interested in botany.

By Professor Julius Nelson, of Rutgers College, two lectures, as follows: “The Fundamental Character of Protoplasm;” “Heredity of Sex.”

By Professor Conn, one lecture on “Modern Theories of Heredity.”

These lectures have been attended by all of the students in the laboratory and have been supplementary to the regular work.

Seventh. The course of evening lectures, have been even more successful during the present year. The Wauwepex Society, founded by Mr. John D. Jones, during the last year, has fitted up for the use of the laboratory, a pleasant lecture room accommodating about 120 persons. It is near the hatchery and conveniently located for the people of Cold Spring Harbor. A lantern for lecture illustrations has been furnished by the Brooklyn Institute and a large number of lantern slides have been made use of by the various lecturers. The slides have been partly furnished by the Brooklyn Institute, partly by the different lecturers and have been partly made at the laboratory. The number of lectures during the summer has been sixteen, nearly all of which have been illustrated by the use of the lantern. The attendance on these lectures has been large, the hall being filled in some cases, and a good sized audience being always present. The interest in the lectures has constantly grown during the summer and the last two lectures were more fully attended than any of the others. The people of Cold Spring Harbor evidently have appreciated the kindness of the different lecturers in giving these lectures, and the interest taken in them has testified to the increasing popularity of the laboratory among the people of the place. The lectures for the summer have been as follows:

July fifth, by Professor Conn: “Biological Laboratories in General and the Cold Spring Laboratory in Particular.”

July fourteenth, Professor F.W. Hooper, of the Brooklyn Institute: “The Geology of the White Mountains.” Illustrated.

July fifteenth, Professor C.W. Hargitt, of Syracuse University: “Coral Islands.” Illustrated.

July nineteenth, Professor F.W. Hooper: “The Geology of the Adirondacks.” Illustrated.

July twenty first, Professor Byron D. Halsted, of Rutgers College: “The Dissemination and Dispersal of Plant Offspring.” Illustrated.

July twenty-sixth, Dr. Thomas Morong, of Columbia College Herbarium: “The Geography of the La Platta, its People and its Flora.” Illustrated.

July twenty-eighth, Dr. Thomas Morong: “Life of the La Platta, Extinct and Existing.” Illustrated.

August second, Professor C.W. Hargitt: “The Origin of the Soil.” Illustrated.

August third, Professor Julius Nelson, of Rutgers College: “The Development of the Chick.” Illustrated.

August fourth, Professor John B. Smith, of Ruters College: “The Respiratory and Nervous System of Insects.” Illustrated.

August fifth, Professor John B. Smith: “Digestive Structures and Habits of Insects.” Illustrated.

August ninth, Professor H.T. Osborn, of Columbia College: “Studies in Evolution.”

August eleventh, Professor H.L. Osborn, of Hamline University: “Structural Adaptation and Habits Among Rodents.” Illustrated.

August sixteenth, Professor H.W. Conn: “The Danger of Interfering with Nature.” Illustrated.

August eighteenth, Professor H.W. Conn: “Methods of Defense Among Animals.” Illustrated.

During the summer, several conferences were held by the director with the members of the Wauwepex Society, in reference to the erection of a laboratory building for the use of the school. At the request of the secretary of that society sketch plans were prepared by the director, with the aid of Professor Hooper, and these plans have been submitted to the Wauwepex Society and are now in their hands. The generosity of this society, their interest in our work and their evident desire to erect a building for us, gives every hope that a building for the purpose will be erected during the coming year. This society intends also to improve the general accommodations for students by furnishing better lodging quarters and comfortable boarding arrangements.

**************

Report of the Cold Spring Harbor Station

by Fred Mather, Superintendent

from Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Issues 35-42, by New York (State) Legislature Assembly

1892

To the Commissioners of Fisheries of New York:

Gentlemen. – The following is a statement of the operations at this station for the year ending September 30, 1892.

The new pond mentioned in last report was finished this year, but the water has not been let in it. The work of shad hatching on the Hudson left the station short-handed in May and June and the appropriation did not allow the hiring of other men for work on the grounds. During July and August Peter Gorman was on the payroll of the Biological Laboratory and only after September first did new work begin. In May stone for walls was procured and a portion of it used to build a wall in the fresh-water reservoir on the west side, to widen the walk there.

The output from the station was, in eggs, fry and adult fish of the several kinds, 7,685,866, exclusive of 2,436,000 shad planted in the Hudson. The details of the different species and the plantings will be given farther on.

The Biological Laboratory of the Brooklyn Institute held its session in the hatchery again during July and August by day, but had an old building refitted for the popular evening lectures, where the seating capacity was greater and where a higher ceiling gave better facilities for stereopticon views. The naphtha launch owned by the laboratory was loaned us and was very useful. The launch was disabled early in the season and had to be sent to New York for repairs, or we might have obtained more lobster eggs than we did.

An event in the fish cultural history of the State was the fitting of the railway car “Adirondack” with apparatus for shad hatching, an account of which will be found under a subhead.

Railroad and Express Companies

This year we were again under obligations to Mr. Austin Corbin for passes for our men and cans over the Long Island railroad and to Mr. M.H. Hubbell, superintendent of the Long Island Express Company, who promptly forwarded our cans to other railroads.

The National Express Company, through its vice-president and general manager, Col. Locke W. Winchester, gave us the privilege of their cars for our cans and messengers, as in former years.

The Epidemic of 1890

In 1891 there was no appearance of this disease (see twentieth report, pp. 44-49) except in a few individual trout, perhaps a dozen, and at as many intervals. This year something of the kind appeared but was, with rare exceptions, confined to the rainbow and brook trout yearlings. A loss occurred during May and June, when I was absent in part, fitting the car for shad hatching and was short-handed; not in July and August, as in 1890. This loss was seldom accompanied by a sore on the skin as in 1890.

In my last report I showed (pp. 44-49) that this disease covered a wide territory, and had been observed by many trout breeders who had never mentioned it publicly, and also that such occurrences were not confined to trout, but extended to other fishes, both in fresh and salt water. Since the last report was written I have the following letters:

New York, February 6, 1892.

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Mr. Cheney wrote you regarding a disease that is carrying off some of our three inch trout at Madison, Conn., but he did not have all the facts. There is no fungus about it, for I have had specimens of dead fish sent to me. We have the fry in charred tanks, ten by three feet, supplied by running water, in which the native trout do well. There are about 1,000 fish to each tank. Older trout in a larger pond, covered in and supplied with the same water after it has run through the first house, are O.K., and we have not lost a fish since last June, and, up to the present time, the little fellows are well. They are affected thus: A trout will by lying, apparently well and happy, in the current and will suddenly dash about and then come back to its place. This is repeated several times and death takes place in four or five hours. This looks like some irritation or congestion of the cerebro-spinal system, but my books are silent in regard to the malady. Can you write me as to its prevention and cure? Whatever you may write will be deeply appreciated.

Yours cordially.

(Signed.) John D. Quackenbos.

I replied to Dr. Quackenbos that I had seen such deaths often, but the epidemic of 1890 seemed different; the darting, turning on the side and turning belly up for hours and even days before death were seldom accompanied by the white spot which developed into a hole as described in my last report and which marked the epidemic of 1890, as I call it, for lack of a better name, and described it in more detail, assuring him that I was then, as now, ignorant of its cause or cure. Under date of February 15, 1892, Dr. Quackenbos wrote again as follows:

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Your letter was received and read with interest. Mr. Cheney forwarded to me the letters which you sent him, and I like your clean cut way of dealing with the conflicting accounts of symptoms. Beach and Bartlett are now assimilating what you have written.

Cordially yours,

(Signed.) John D. Quackenbox.

One of the curious things in this connection is the fact that in 1892 we had an experience similar to that at Meridan, Conn., the year before, as related by Dr. Quackenbos. We lost numbers of yearlings from three to five inches in length which were, as at Meridan, above the larger fish where the loss was lighter. In 1891 there was the usual mortality that is always present among fish as among other live stock.

Mr. Charles G. Atkins, superintendent of the United States salmon station, at Craigs Brook, Maine, wrote me about an epidemic among his salmon fry which occurred this year and was similar, if not identical, with one that I described in the eleventh report of the American Fish Cultural Association (1882), pages 7-11, but as this was not the same as the scourge of 1890 I pass it.

Another cause of mortality among trout in ponds tempts me to speak of it. In answer to my circular of last year came a response from Mr. G.M. Robinson, Mammoth Springs, Ark., who, under date of May 26, 1891, writes:

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Pray excuse this delay in answering your circular but will say: The disease which you mention is new to me, have never seen a trout so affected. My experience in this locality is limited, but I notice that the brook trout in this locality are subject to a disease which I have noticed before. It occurs during the summer months and the eye of the fish becomes inflamed and protrudes from the head fully one quarter of an inch, sometimes only one eye and occasionally both. They linger and after some months will die. We call it the big-eye.* [I never had a name for this, but my foreman, Mr. Walters, came very near Mr. Robinson’s name when he christened it “bug-eye,” merely the difference of a letter. F.M.]

This “big eye” caused a company at this place, called the Mammoth Springs Fish Farm Company+ [This is the company which exhibited trout in Fulton market, New York, last spring and caused so much astonishment that our brook trout could live as far south as Arkansas. F.M.] to lose large numbers of trout last summer. We laid it to overfeeding and have reduced the food and will soon change it entirely to natural food such as fresh-water shrimp and minnows which can be furnished in large quantities here.

Very truly.

(Signed.) E.M. Robinson.

This “big eye” or “bug eye” is a familiar disease to me and I believe that I know its cause. In a recent report of the Wisconsin Fish Commission this disease is spoken of as very prevalent, and it was with me at my private trout ponds at Honeoye Falls, Monroe County, N.Y., 1868 to 1876. A look at the picture of the ponds at the Wisconsin Commission shows that they are parallelograms with vertical stone walls on both sides and ends, exactly as mine were built, and the trout when alarmed from any cause would strike the walls squarely with their noses and the concussion caused inflammation of the optic never, or nerves, and the result would be the protrusion and loss of one or both eyes and usually death. I have long ceased building ponds with four vertical sides or with square ends.

Fish Food.

In all my former reports I have mentioned this subject and have been continually on the lookout for the best and cheapest food. We began feeding soft clams (Mya arenaria) and mussels (Mytilus edulis), and continued it for several years until the supply was running short in the harbor and people complained that we were getting more than our share. Then I tried beef livers, sent from New York city, but the supply was not regular and the express charges made the cost too high. See last report, pp. 49-50. Since November, 1891, we have been feeding horse beef, which is delivered at the station, free from fat and bone, for four cents per pound. I am not prepared to say how this will suit on only one season’s trial. Our fish of last spring’s hatch did not grow as large as those in former years did, and there might be other causes besides the food. The older fish have done fairly well on it and I would prefer to try it another year before either praising or condemning it.

Brook Trout.

From forty female trout we took 83,365 eggs the size of which varied from 300 to 530 to the fluid ounce. There being in all 194 ounces the average size was a trifle less than 430 eggs to the ounce. The fish began spawning on November fourth and ended on December seventh, and only on eighteen days between these dates, did we take eggs.

We received 20,000 eggs from the Caledonia Station on December twenty-fifth, and on January nineteenth, we received 75,000 eggs from the South Side Sportsmen’s Club, of long Island, in exchange for eggs of brown trout. This made a total of 178,000 eggs. There were many unimpregnated eggs this year and this swelled the loss, which in eggs and fry amounted to over 64,000. We planted 78,600 as per table. On November nineteenth, I sent Messrs. Walters and Rogers to Smithtown to try to get eggs from the grounds of the Brush club. They stayed there over a week without result…..

Death of Hon. Dr. von Behr

I cannot close without noticing the death of our good friend and patron of fish culture, Dr. Friederich Felix von Behr, President of the German Fishery Association, and one of the most active men to promote the interests of fish culture not only in his own land but in all others. As a friend of our late lamented Professor Spencer F. Baird, he inaugurated a system of international exchanges of fish and fishcultural literature that was productive of great good and was continued until both these great men died. It was to Baron von Behr that I owed the personal present of the first brown trout eggs that were sent to America, a species which now are so common. A half forgotten remark to him in 1879 that the fish I had taken in the Black Forest should be introduced into America if opportunity offered, brought a consignment of eggs when he heard that I was in charge of a hatchery station in 1883. His death on January 13, 1892, was a loss to fish culture the world over.

All of which is respectfully submitted.

Fred Mather

Superintendent.

by H.W. Conn, Ph.D., Commissioners of Fisheries

from Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Issues 35-42, by New York (State) Legislature Assembly

1892

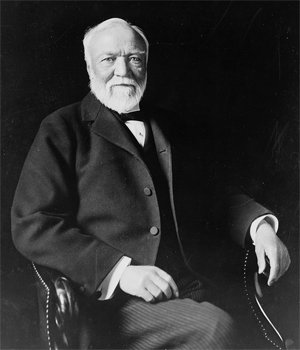

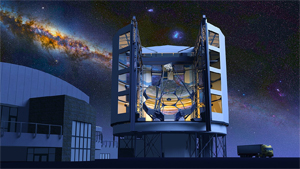

At the end of the 19th century, the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences founded a laboratory for training high school and college teachers in marine biology. As biologists and naturalists of that time worked out the consequences of Darwin’s theory of evolution, they often established their laboratories at the seashore, where there was an abundance of animals and plants for study. In 1889, John D. Jones [Wauwepex Society] gave land and buildings (formerly part of the Cold Spring Whaling Company) on the southwestern shore of Cold Spring Harbor to the Brooklyn Institute for Arts and Science (BIAS). BIAS used the Jones gift to established its presence in Cold Spring Harbor as the Biological Laboratory (Bio Lab) engaged in science research and training of secondary school teachers. In 1917 the Bio Lab officially became one of the four departments of the BIAS (along with the Brooklyn Art Museum, Brooklyn Botanical Garden and Brooklyn Zoo) and an endowment was raised from contributions of interested Cold Spring Harbor neighbors. In 1924 BIAS turned over the administration and ownership of the Biological Lab to the Cold Spring Harbor community and it incorporated as the Long Biological Association (LIBA). LIBA was initially administered by Director Reginald Harris, and continued as a scientific research and educational institution, funded by local residents and a far reaching list of private donors.

-- Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences: The Biological Laboratory Collection, by Archives at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

As director of the biological laboratory for the session of 1892, I will present the following report:

The laboratory has been in session for eight weeks, from July sixth to August twenty eighth, as announced in the prospectus. During that time, the following persons have been present as instructors or lecturers:

Board of Instruction.

Professor Herbert W. Conn, Ph.D., Wesleyan University, director of the laboratory.

Professor Charles W. Hargitt, Ph.D., Syracuse University, associate director.

Professor Henry L. Osborn, Ph.D., Hamline University, associate director.

Lecturers.

Professor Henry F. Osborn, Columbia College.

Professor John B. Smith, Rutgers College.

Professor Byron D. Halstead, Rutgers College.

Dr. Thomas Morong, Columbia College, Herbarium.

Professor Franklin W. Hooper, Brooklyn Institute.

Professor Julius Nelson, Rutgers College.

As students in the laboratory, taking the regular courses, there have been present fifteen persons, as follows:

Louis Curtis Ager, student, Long Island Hospital.

E.V. Agramonte, M.D., physician, New York city.

Miss Ida W. Aikman, teacher, Brooklyn.

Miss Martha T. Austin, teacher, Easthampton, Mass.

John T. Barnhart, instructor, Wesleyan University.

Miss Edith M. Brace, student, University of Nebraska.

Miss Lillie C. Brown, teacher, New Britain, Conn.

Duncan S. Johnson, instructor, Wesleyan University.

Franklin T. Kurt, student, Wesleyan University.

James T. O’Connor, M.D., Ph.D., physician, New York city.

Mrs. James T. O’Connor, M.D., clinical professor, New York Medical College and Hospital for Women.

Miss M. Josephine Shepard, teacher, Brooklyn.

Miss Elizabeth M. Sturgis, student, New York city.

William W. Vibbart, student, Trinity College.

Walter S. Watson, student, Wesleyan University.

During the summer the work at the laboratory has been as follows:

First. A course in general zoology. – The outline of this course has been practically the same as that of the course given during the previous year, and has consisted of daily lectures and laboratory excercises. For reasons which were given in my last report, the course of regular class instruction lasted only the first six weeks of the session, the last two weeks being devoted to more independent work on the part of the students upon special subjects of their own choosing. This course in zoology has been given conjointly by the director and the associate directors. Professor Hargitt has conducted the work upon protozoa, coelentera and echinoderma. Professor Osborn has had charge of the work upon molluska and arthropoda, and Professor Conn, the work upon vermes, annelid and vertebrates. Nearly all of the students in the laboratory took the whole of this course.

Second. A course of practical work in bacteriology. – This course has been like that of last year, and has consisted of elementary instruction in bacteriological methods, such as making culture fluids, staining bacteria, etc. No definite instruction has been given, but personal direction to those wishing work along this line.

Third. A course of twelve lectures has been given by Professor Conn upon the history of bacteriology. This course has been a popular course, designed for all persons present at the laboratory, and has given an elementary outline of the history of the development of the study of bacteriology and of all the important facts discovered up to the present time.

Fourth. A large amount of miscellaneous work has been done by different members of the party. It has included staining and mounting microscopic specimens, section cutting, and other work in historical technique, the study of embryology of several types, study of flowers and preparing of herbaria, and a large amount of general zoology and collecting.

Fifth. Original investigations have been undertaken by members of the laboratory staff and by some of the visitors from other colleges. The work has comprised the following subjects: Study of the new species of hydroids; the embryological development of crustacean; systematic study of salt water protozoa; bacteriological study of a disease attacking the trout in the fish hatchery.

Sixth. In addition to the regular work, a number of miscellaneous lectures have been given in the laboratory. These have been as follows:

By Professor F.W. Hooper, “Agassiz at Penakese.”

By Dr. Morong, “Orchidaceae.” Under the guidance of Dr. Morong, three botanical excursions have been taken by those interested in botany.

By Professor Julius Nelson, of Rutgers College, two lectures, as follows: “The Fundamental Character of Protoplasm;” “Heredity of Sex.”

By Professor Conn, one lecture on “Modern Theories of Heredity.”

These lectures have been attended by all of the students in the laboratory and have been supplementary to the regular work.

Seventh. The course of evening lectures, have been even more successful during the present year. The Wauwepex Society, founded by Mr. John D. Jones, during the last year, has fitted up for the use of the laboratory, a pleasant lecture room accommodating about 120 persons. It is near the hatchery and conveniently located for the people of Cold Spring Harbor. A lantern for lecture illustrations has been furnished by the Brooklyn Institute and a large number of lantern slides have been made use of by the various lecturers. The slides have been partly furnished by the Brooklyn Institute, partly by the different lecturers and have been partly made at the laboratory. The number of lectures during the summer has been sixteen, nearly all of which have been illustrated by the use of the lantern. The attendance on these lectures has been large, the hall being filled in some cases, and a good sized audience being always present. The interest in the lectures has constantly grown during the summer and the last two lectures were more fully attended than any of the others. The people of Cold Spring Harbor evidently have appreciated the kindness of the different lecturers in giving these lectures, and the interest taken in them has testified to the increasing popularity of the laboratory among the people of the place. The lectures for the summer have been as follows:

July fifth, by Professor Conn: “Biological Laboratories in General and the Cold Spring Laboratory in Particular.”

July fourteenth, Professor F.W. Hooper, of the Brooklyn Institute: “The Geology of the White Mountains.” Illustrated.

July fifteenth, Professor C.W. Hargitt, of Syracuse University: “Coral Islands.” Illustrated.

July nineteenth, Professor F.W. Hooper: “The Geology of the Adirondacks.” Illustrated.

July twenty first, Professor Byron D. Halsted, of Rutgers College: “The Dissemination and Dispersal of Plant Offspring.” Illustrated.

July twenty-sixth, Dr. Thomas Morong, of Columbia College Herbarium: “The Geography of the La Platta, its People and its Flora.” Illustrated.

July twenty-eighth, Dr. Thomas Morong: “Life of the La Platta, Extinct and Existing.” Illustrated.

August second, Professor C.W. Hargitt: “The Origin of the Soil.” Illustrated.

August third, Professor Julius Nelson, of Rutgers College: “The Development of the Chick.” Illustrated.

August fourth, Professor John B. Smith, of Ruters College: “The Respiratory and Nervous System of Insects.” Illustrated.

August fifth, Professor John B. Smith: “Digestive Structures and Habits of Insects.” Illustrated.

August ninth, Professor H.T. Osborn, of Columbia College: “Studies in Evolution.”

August eleventh, Professor H.L. Osborn, of Hamline University: “Structural Adaptation and Habits Among Rodents.” Illustrated.

August sixteenth, Professor H.W. Conn: “The Danger of Interfering with Nature.” Illustrated.

August eighteenth, Professor H.W. Conn: “Methods of Defense Among Animals.” Illustrated.

During the summer, several conferences were held by the director with the members of the Wauwepex Society, in reference to the erection of a laboratory building for the use of the school. At the request of the secretary of that society sketch plans were prepared by the director, with the aid of Professor Hooper, and these plans have been submitted to the Wauwepex Society and are now in their hands. The generosity of this society, their interest in our work and their evident desire to erect a building for us, gives every hope that a building for the purpose will be erected during the coming year. This society intends also to improve the general accommodations for students by furnishing better lodging quarters and comfortable boarding arrangements.

**************

Report of the Cold Spring Harbor Station

by Fred Mather, Superintendent

from Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Issues 35-42, by New York (State) Legislature Assembly

1892

To the Commissioners of Fisheries of New York:

Gentlemen. – The following is a statement of the operations at this station for the year ending September 30, 1892.

The new pond mentioned in last report was finished this year, but the water has not been let in it. The work of shad hatching on the Hudson left the station short-handed in May and June and the appropriation did not allow the hiring of other men for work on the grounds. During July and August Peter Gorman was on the payroll of the Biological Laboratory and only after September first did new work begin. In May stone for walls was procured and a portion of it used to build a wall in the fresh-water reservoir on the west side, to widen the walk there.

The output from the station was, in eggs, fry and adult fish of the several kinds, 7,685,866, exclusive of 2,436,000 shad planted in the Hudson. The details of the different species and the plantings will be given farther on.

The Biological Laboratory of the Brooklyn Institute held its session in the hatchery again during July and August by day, but had an old building refitted for the popular evening lectures, where the seating capacity was greater and where a higher ceiling gave better facilities for stereopticon views. The naphtha launch owned by the laboratory was loaned us and was very useful. The launch was disabled early in the season and had to be sent to New York for repairs, or we might have obtained more lobster eggs than we did.

Brooklyn Institute of arts and sciences -- Biological laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island ... Announcement for the summer of 1904, fifteenth season, illus. 22cm. [n.p., 1904]

An event in the fish cultural history of the State was the fitting of the railway car “Adirondack” with apparatus for shad hatching, an account of which will be found under a subhead.

Railroad and Express Companies

This year we were again under obligations to Mr. Austin Corbin for passes for our men and cans over the Long Island railroad and to Mr. M.H. Hubbell, superintendent of the Long Island Express Company, who promptly forwarded our cans to other railroads.

The National Express Company, through its vice-president and general manager, Col. Locke W. Winchester, gave us the privilege of their cars for our cans and messengers, as in former years.

The Epidemic of 1890

In 1891 there was no appearance of this disease (see twentieth report, pp. 44-49) except in a few individual trout, perhaps a dozen, and at as many intervals. This year something of the kind appeared but was, with rare exceptions, confined to the rainbow and brook trout yearlings. A loss occurred during May and June, when I was absent in part, fitting the car for shad hatching and was short-handed; not in July and August, as in 1890. This loss was seldom accompanied by a sore on the skin as in 1890.

In my last report I showed (pp. 44-49) that this disease covered a wide territory, and had been observed by many trout breeders who had never mentioned it publicly, and also that such occurrences were not confined to trout, but extended to other fishes, both in fresh and salt water. Since the last report was written I have the following letters:

New York, February 6, 1892.

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Mr. Cheney wrote you regarding a disease that is carrying off some of our three inch trout at Madison, Conn., but he did not have all the facts. There is no fungus about it, for I have had specimens of dead fish sent to me. We have the fry in charred tanks, ten by three feet, supplied by running water, in which the native trout do well. There are about 1,000 fish to each tank. Older trout in a larger pond, covered in and supplied with the same water after it has run through the first house, are O.K., and we have not lost a fish since last June, and, up to the present time, the little fellows are well. They are affected thus: A trout will by lying, apparently well and happy, in the current and will suddenly dash about and then come back to its place. This is repeated several times and death takes place in four or five hours. This looks like some irritation or congestion of the cerebro-spinal system, but my books are silent in regard to the malady. Can you write me as to its prevention and cure? Whatever you may write will be deeply appreciated.

Yours cordially.

(Signed.) John D. Quackenbos.

I replied to Dr. Quackenbos that I had seen such deaths often, but the epidemic of 1890 seemed different; the darting, turning on the side and turning belly up for hours and even days before death were seldom accompanied by the white spot which developed into a hole as described in my last report and which marked the epidemic of 1890, as I call it, for lack of a better name, and described it in more detail, assuring him that I was then, as now, ignorant of its cause or cure. Under date of February 15, 1892, Dr. Quackenbos wrote again as follows:

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Your letter was received and read with interest. Mr. Cheney forwarded to me the letters which you sent him, and I like your clean cut way of dealing with the conflicting accounts of symptoms. Beach and Bartlett are now assimilating what you have written.

Cordially yours,

(Signed.) John D. Quackenbox.

One of the curious things in this connection is the fact that in 1892 we had an experience similar to that at Meridan, Conn., the year before, as related by Dr. Quackenbos. We lost numbers of yearlings from three to five inches in length which were, as at Meridan, above the larger fish where the loss was lighter. In 1891 there was the usual mortality that is always present among fish as among other live stock.

Mr. Charles G. Atkins, superintendent of the United States salmon station, at Craigs Brook, Maine, wrote me about an epidemic among his salmon fry which occurred this year and was similar, if not identical, with one that I described in the eleventh report of the American Fish Cultural Association (1882), pages 7-11, but as this was not the same as the scourge of 1890 I pass it.

Another cause of mortality among trout in ponds tempts me to speak of it. In answer to my circular of last year came a response from Mr. G.M. Robinson, Mammoth Springs, Ark., who, under date of May 26, 1891, writes:

Mr. Fred Mather:

Dear Sir. – Pray excuse this delay in answering your circular but will say: The disease which you mention is new to me, have never seen a trout so affected. My experience in this locality is limited, but I notice that the brook trout in this locality are subject to a disease which I have noticed before. It occurs during the summer months and the eye of the fish becomes inflamed and protrudes from the head fully one quarter of an inch, sometimes only one eye and occasionally both. They linger and after some months will die. We call it the big-eye.* [I never had a name for this, but my foreman, Mr. Walters, came very near Mr. Robinson’s name when he christened it “bug-eye,” merely the difference of a letter. F.M.]

This “big eye” caused a company at this place, called the Mammoth Springs Fish Farm Company+ [This is the company which exhibited trout in Fulton market, New York, last spring and caused so much astonishment that our brook trout could live as far south as Arkansas. F.M.] to lose large numbers of trout last summer. We laid it to overfeeding and have reduced the food and will soon change it entirely to natural food such as fresh-water shrimp and minnows which can be furnished in large quantities here.

Very truly.

(Signed.) E.M. Robinson.

This “big eye” or “bug eye” is a familiar disease to me and I believe that I know its cause. In a recent report of the Wisconsin Fish Commission this disease is spoken of as very prevalent, and it was with me at my private trout ponds at Honeoye Falls, Monroe County, N.Y., 1868 to 1876. A look at the picture of the ponds at the Wisconsin Commission shows that they are parallelograms with vertical stone walls on both sides and ends, exactly as mine were built, and the trout when alarmed from any cause would strike the walls squarely with their noses and the concussion caused inflammation of the optic never, or nerves, and the result would be the protrusion and loss of one or both eyes and usually death. I have long ceased building ponds with four vertical sides or with square ends.

Fish Food.

In all my former reports I have mentioned this subject and have been continually on the lookout for the best and cheapest food. We began feeding soft clams (Mya arenaria) and mussels (Mytilus edulis), and continued it for several years until the supply was running short in the harbor and people complained that we were getting more than our share. Then I tried beef livers, sent from New York city, but the supply was not regular and the express charges made the cost too high. See last report, pp. 49-50. Since November, 1891, we have been feeding horse beef, which is delivered at the station, free from fat and bone, for four cents per pound. I am not prepared to say how this will suit on only one season’s trial. Our fish of last spring’s hatch did not grow as large as those in former years did, and there might be other causes besides the food. The older fish have done fairly well on it and I would prefer to try it another year before either praising or condemning it.

Brook Trout.

From forty female trout we took 83,365 eggs the size of which varied from 300 to 530 to the fluid ounce. There being in all 194 ounces the average size was a trifle less than 430 eggs to the ounce. The fish began spawning on November fourth and ended on December seventh, and only on eighteen days between these dates, did we take eggs.

We received 20,000 eggs from the Caledonia Station on December twenty-fifth, and on January nineteenth, we received 75,000 eggs from the South Side Sportsmen’s Club, of long Island, in exchange for eggs of brown trout. This made a total of 178,000 eggs. There were many unimpregnated eggs this year and this swelled the loss, which in eggs and fry amounted to over 64,000. We planted 78,600 as per table. On November nineteenth, I sent Messrs. Walters and Rogers to Smithtown to try to get eggs from the grounds of the Brush club. They stayed there over a week without result…..

Death of Hon. Dr. von Behr

I cannot close without noticing the death of our good friend and patron of fish culture, Dr. Friederich Felix von Behr, President of the German Fishery Association, and one of the most active men to promote the interests of fish culture not only in his own land but in all others. As a friend of our late lamented Professor Spencer F. Baird, he inaugurated a system of international exchanges of fish and fishcultural literature that was productive of great good and was continued until both these great men died. It was to Baron von Behr that I owed the personal present of the first brown trout eggs that were sent to America, a species which now are so common. A half forgotten remark to him in 1879 that the fish I had taken in the Black Forest should be introduced into America if opportunity offered, brought a consignment of eggs when he heard that I was in charge of a hatchery station in 1883. His death on January 13, 1892, was a loss to fish culture the world over.

All of which is respectfully submitted.

Fred Mather

Superintendent.