Part 2 of 2

DOUCHING FOR VAGINOSIS OR VAGINITISThe near-universal medical view is that douching is not needed for routine vaginal hygiene (145). Monif (34) argues, however, that there is a role for douching among women with symptomatic vaginitis or vaginosis. Monif argues that douching is probably a behavioral response to an abnormal vaginal ecology, a factor not taken into account in cross-sectional studies, such that douching appears to be a cause when it is more likely to be a consequence. Monif (34) further argues that available microbiologic data indicate douching to be harmless. Separate studies by Monif et al. (33) and by Osborne and Wright (146) suggested a positive effect of douching, as in the case of using antibacterial douches to replace systemic antibiotics during vaginally related surgery. Monif et al. (33) found that a povidone-iodine douche produced a dramatic fall in the total bacteria in the vagina for the first 10 minutes following administration. Within 2 hours, near baseline counts were reestablished, suggesting a benign nature of single episode douching.

Three vinegar-containing douches tested by Pavlova and Tao (30) were selectively inhibitory against vaginal pathogens associated with bacterial vaginosis, group B streptococcal vaginitis, and candidiasis, but not lactobacilli, giving a preliminary suggestion that vinegar douches could be beneficial for treating some vaginal infections. Beaton et al. (147) found that, in women with minor vaginal irritation of unknown etiology, short-term use of a medicated povidone-iodine douche preparation resulted in improvement of symptoms, including discharge, odor, pruritus, erythema, burning, and discomfort; 94 percent of the 185 patient complaints were cleared completely. They found that 98 percent of the patients responded favorably to the douche, with no adverse effects reported. Manzardo et al. (148) found that a tetridamine vaginal lavage, twice daily for 7 days, reduced or eliminated all inflammation symptoms such as burning and leucorrhea in women with vulvovaginitis and cervicitis.

In a 1997 meeting of the Nonprescription Drug Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration (149), Dr. Andrew Onderdonk presented data looking at women with abnormal vaginal ecology, such as women with culture-positive vaginal yeast infections (32). His group treated women with either sterile water, a vinegar and water douching solution, or a povidone-iodine solution. Twenty-four hours after treatment with the various douche solutions, the only women whose vaginal microflora returned to normal were the women who used the povidone-iodine douche. This suggested that, in women who have an abnormal vaginal ecology, perhaps due to a vaginal yeast infection, douching with povidone-iodine may be beneficial and may help to return the vaginal ecology back to normal values.

Testing this concept in a controlled clinical trial is problematic, however, given the known risks of douching. It is unlikely that a peer review committee or a research ethics board would see merit in deliberately allocating women to a “douching encouraged” group.Nonpregnant women who are symptomatic may derive some benefit from vaginal douching, specifically with povidone-iodine, if they have abnormal vaginal ecology. However, given the many studies that have suggested adverse effects from douching compared with the very few studies that have shown a potential benefit, douching cannot be a recommended therapy and is surely not indicated for routine vaginal “hygiene.”

INTRAPARTUM OR ROUTINE HYGIENIC DOUCHINGDouching has also been used in pregnant women in labor. Stray-Pedersen et al. (150) found that intrapartum vaginal douching with 0.2 percent chlorhexidine significantly reduced mother-to-child transmission of vaginal microorganisms, such as Streptococcus agalactiae, and both maternal and early neonatal infectious morbidity. Dykes et al. (151) found that a single washing of the urogenital tract with 0.5 g of chlorhexidine per liter in women who were carriers of group B streptococci in weeks 38-40 of pregnancy resulted in a suppression of the number of colony-forming units of group B streptococci. However, Sweeten et al. (152) found that a one-time 0.4 percent chlorhexidine vaginal wash in laboring pregnant women did not decrease the incidence of infectious morbidity in parturients, as compared with the use of sterile water. Taha et al. (153) noted reduced maternal and newborn sepsis rates postpartum with use of an intrapartum 0.2 percent vaginal chlorhexidine wash. Neither Gaillard et al. (154) nor Biggar et al. (155) found vaginal lavage ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 percent chlorhexidine to be protective for mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission. The above studies in pregnant women look primarily at one time douching that has little to do with typical, repetitive use of douching for hygienic reasons. However, limited vaginal lavage has utility in transient reduction of pathogenic vaginal organisms intrapartum.

Women without vaginal symptoms primarily douche for perceived hygienic or aesthetic benefit. Postcoital douching has been suggested for two purposes, reducing semen exposure to prevent pregnancy and to prevent human immunodeficiency virus transmission. After sexual intercourse, semen increases the pH of the vagina that facilitates sperm motility (144). Douching can dilute and wash out semen and can help return the vagina to its normal acidity, theoretically helping to prevent heterosexual human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Obaidullah (156) found that women who used a Betadine Vaginal Cleansing Kit before and after insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device showed a marked absence of bacterial growth 4-6 weeks later, compared with control volunteers who used no cleansing agents. The investigators speculated that an absence of bacterial growth in the study group could help to minimize the risk of intrauterine device-related pelvic infection. These speculations and highly limited data do not, however, suggest that douching can be advocated for women. One could just as easily speculate that douching increases human immunodeficiency virus risk, increases pregnancy risk (by pressure forcing sperm into the endocervical canal, for instance), or exacerbates intrauterine device-related risks.

Despite a few dissenting views, the preponderance of the evidence suggests that douching is not necessary or beneficial and is very likely to be harmful (2-4, 6, 157-161). Multiple case reports indicate occasional very serious douching-related harm. Safran and Braverman (162) found that douching daily with polyvinylpyrrolidone-iodine for 14 days resulted in a significant increase in serum total iodine concentration and urine iodine excretion, followed by an increase in serum thyrotropin, although never above the normal range. They concluded that iodine is absorbed across the vaginal mucosa and that the subsequent increase in serum total iodine causes subtle increases in serum thyrotropin but with no overt hypothyroidism. Udoma et al. (163) reported a rectovaginal fistula following coitus in a woman in Nigeria after douching with aluminum potassium sulfate dodecahydrate (potassium alum) prior to intercourse. Vaginal douching with a bulb syringe or effervescent fluid has been reported as a cause of asymptomatic, spontaneous pneumoperitoneum (157, 164).

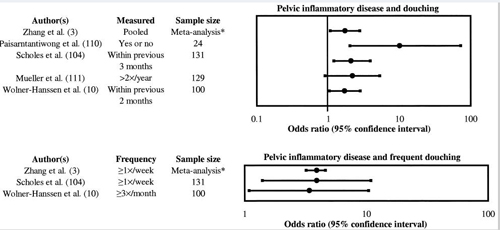

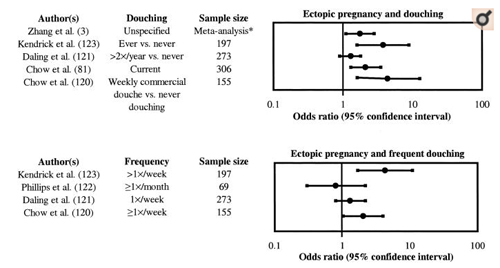

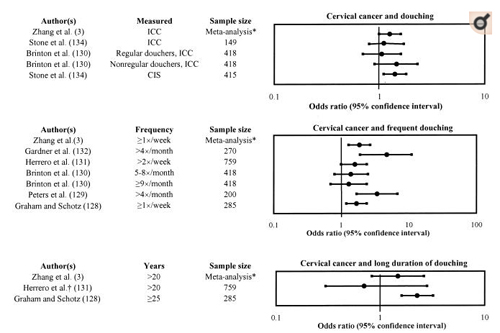

MEDICAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS AND DOUCHINGThere is no official medical or public health advisory policy on whether douching should be discouraged. In January 2001, various medical organizations were contacted via e-mail and their Web sites were searched for information pertaining to vaginal douching. The following organizations replied that they have no official policy statements or positions on the use of vaginal douche products: the American College of Nurse-Midwives, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Medical Association, the American Medical Women's Association, the American Public Health Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization.An American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' technical bulletin (165) states that vaginitis occurs when the vaginal ecosystem is altered, which can result from several factors including repeated douching. The rationale presented in the bulletin is that repeated douching may alter the pH level or suppress growth of normal, endogenous bacteria, leading to vaginitis. A vaginitis information sheet by the American Medical Association (166) states that, in women of childbearing age, vaginitis can be caused by frequent douching. They state that women of all ages can get vaginitis from chemical irritation or an allergic reaction from vaginal douches. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (167) state that, in a study of African-American women, an association has been found between the length of time women douched and their risk of developing ectopic pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (168) have a bacterial vaginosis fact sheet stating that women are at an increased risk for bacterial vaginosis if they douche, because douching upsets the normal balance of vaginal bacteria, and that not douching can lower a woman's risk of developing bacterial vaginosis. In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report article (169) on pelvic inflammatory disease, douching was suggested as a risk factor for pelvic inflammatory disease, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated that the data (as of 1991) did not provide enough information to determine if the positive associations were due to the characteristics of the women who douche or to the douching itself. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention authors found that no definitive conclusion could be reached regarding the relation between douching and pelvic inflammatory disease. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention manual on family planning in Africa cautions against douching as follows: “Douching is unnecessary to maintain vaginal hygiene. Moreover, douching is associated with an increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease and ectopic pregnancy. Pregnant women especially should be warned about the risks associated with douching”(170, p. 195).

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (171) provides a health information sheet on vaginitis that states that douching may cause vaginal irritation and vaginitis. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Institutes of Health both reference press releases on a study by Dr. Donna Day Baird and colleagues that found a dose-response reduction in fertility with increased douching (172). The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (173) has a fact sheet on pelvic inflammatory disease that states that women who douche one or two times a month may be more likely to have pelvic inflammatory disease than those who douche less than once a month. Their fact sheet on sexually transmitted diseases states that, to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, sexually active women should avoid douching because douching removes some of the normal protective bacteria in the vagina and increases the risk of getting some sexually transmitted diseases (174). The fact sheet on vaginal yeast infections (vulvovaginal candidiasis) states that douching may increase the incidence of yeast infections (175). The National Women's Health Information Center (176) has an information sheet specifically on douching, stating that douching makes women more susceptible to bacterial infections and spreads existing infections into the upper reproductive tract. The National Women's Health Information Center claims that women who douche have increased bacterial vaginosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and pelvic inflammatory disease; that douching does not prevent pregnancy but may decrease fertility; and that douching increases the risk of low birth weight babies and ectopic pregnancy. They also state that the safest way to clean the vagina is to let the vagina clean itself, which it does by secreting mucus. Their final recommendation was that, if a woman has vaginal discharge, she should seek medical attention without first douching because washing away the discharge makes it harder to identify the infection. The Surgeon General's office responded to our douching-related queries by referring us to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Although informative fact sheets discourage douching, none of the governmental or private organizations that we contacted has an official position statement that either advocates or discourages douching.On April 15, 1997, the Nonprescription Drug Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration held a meeting to discuss vaginal douching (149). Presentations came from the Food and Drug Administration, the Nonprescription Drug Manufacturers Association, and the Purdue Frederick Company (manufacturer of Betadine medicated douche), among others. The Committee concluded that there was not enough information to determine that a causal relation existed between douching and its adverse outcomes. More research was recommended, and the Food and Drug Administration was urged to look into federal regulation and better product labels. The Committee found that some of the studies had residual confounding due to sexual behavior and underreporting of sexually transmitted diseases. A key point in this argument was that, without determining a temporal relation, the studies so far have not been able to tell which came first, douching or the adverse outcome (sexually transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease, infection), when douching may be undertaken as a way to treat the symptoms of the disease. A representative from the National Women's Health Network stated that douching had no benefit on women's health and enhanced the chances of developing upper reproductive tract infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility. A representative from the Food and Drug Administration's Division of Over-the-Counter Drug Evaluation stated that the Agency considers vaginal douches to be both drugs (because they are sometimes used to treat disease) and cosmetics (because they cleanse and/or scent part of the body). From the Food and Drug Administration's review of epidemiologic studies on vaginal douching (considered published case-control and cross-sectional studies), a consistent moderate adverse or null effect of douching was noted; the evidence was considered suggestive that douching independently raises the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and cervical carcinoma.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONCLUSIONSThe present review suggests that future studies must assess more directly the extent to which douching is a causal factor in diseases such as pelvic inflammatory disease and bacterial vaginosis, or if douching is merely a behavior that is more common among women who are at risk of sexually transmitted diseases and/or that douching is done in response to symptoms (15). The effects of different solutions and devices must be considered in more detail. Perhaps there are adverse effects associated with douching if only certain solutions are used but less or no harm with other solutions.

The weight of the evidence today suggests that stronger regulations for vaginal douche products may be indicated, including ingredient control, clearer labeling, and a required statement on product advertisements and on the products themselves that douche products have no proven medical value and may be harmful. A prospective cohort study or, if serious ethical concerns can be resolved, a randomized clinical trial may address these questions. A randomized “community” trial could be considered, where the communities studied are a large group of people from the same area, such as a college or a city. They could be assigned at random to treatment and no treatment, where the treatment group would receive an educational program regarding the potential dangers associated with douching and the women would be encouraged to not douche. Douching prevalence and sexually transmitted disease rates could be assessed before the educational program and at regular intervals during the program. The no treatment group, receiving no such educational intervention, would be assessed in a similar way. The study endpoint could compare rates of douching and sexually transmitted diseases. However, because motivational factors for douching are individualized and often women strongly feel the need to douche, the educational program may not influence enough women to stop douching, affecting the statistical power of such a study. Feasibility and cost may be prohibitive, in which case we may continue in our present state of knowledge/ignorance.

It is accepted that pregnant women should avoid douching. Intrapartum vaginal antiseptic lavage can be highly beneficial, but this is a completely different irrigation event than repetitive vaginal douching. There are limited data that suggest that douching in symptomatic women may have some utility.

The preponderance of evidence shows an association between douching and numerous adverse outcomes. Most women douche for hygienic reasons; it can be stated with present knowledge that routine douching is not necessary to maintain vaginal hygiene; again, the preponderance of evidence suggests that douching may be harmful. The authors of the present review believe that there is no reason to recommend that any woman douche and, furthermore, that women should be discouraged from douching.

Many women douche, especially African Americans. Because the population-level health risks attributable to this common practice could be very large if douching predisposes to even a fraction of the disease burden discussed in this review, the potential salutary impact of reducing douching activity is substantial. Intervention studies may be the very best way to gain both health benefit and insight into the temporal associations of douching and adverse outcomes.

We also believe that responsible government, health, and professional organizations should reexamine available data and determine if there is enough information to issue clear policy statements on douching. We believe that, when they conduct such reviews, they will conclude, with us, that since there are no demonstrated benefits to douching and considerable evidence of harm, women should be encouraged to not douche.ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThis work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant U19 AI-38514 (University of Alabama at Birmingham Sexually Transmitted Disease Cooperative Research Center, E. Hook III, Principal Investigator) and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Scientist Training Program.

The authors thank Ellen Funkhouser and M. Kim Oh for discussion and comments.

AbbreviationsCI confidence interval

OR odds ratio

RR risk ratio

REFERENCES1. Aral SO, Mosher WD, Cates W., Jr Vaginal douching among women of reproductive age in the United States: 1988. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:210–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Chacko MR, McGill L, Johnson TC, et al. Vaginal douching in teenagers attending a family planning clinic. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989;10:217–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Zhang J, Thomas AG, Leybovich E. Vaginal douching and adverse health effects: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1207–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Merchant JS, Oh K, Klerman LV. Douching: a problem for adolescent girls and young women. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:834–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Abma JC, Chandra A, Mosher WD, et al. Fertility, family planning, and women's health: new data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat 23. 1997;19:1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Foch B, McDaniel N, Chacko M. Vaginal douching in adolescents attending a family planning clinic. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2000;13:92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Foch BJ, McDaniel ND, Chacko MR. Racial differences in vaginal douching knowledge, attitude, and practices among sexually active adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Vermund SH, Sarr M, Murphy DA, et al. Douching practices among HIV infected and uninfected adolescents in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. La Ruche G, Messou N, Ali-Napo L, et al. Vaginal douching: association with lower genital tract infections in African pregnant women. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:191–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, Paavonen J, et al. Association between vaginal douching and acute pelvic inflammatory disease. JAMA. 1990;263:1936–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Voigt LF, et al. Vaginal douching and reduced fertility. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:844–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Saraiya M, Berg CJ, Kendrick JS, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Fiscella K, Franks P, Kendrick JS, et al. The risk of low birth weight associated with vaginal douching. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:913–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Scholes D, Stergachis A, Ichikawa LE, et al. Vaginal douching as a risk factor for cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:993–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Rosenberg MJ, Phillips RS, Holmes MD. Vaginal douching. Who and why? J Reprod Med. 1991;36:753–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Rosenberg MJ, Phillips RS. Does douching promote ascending infection? J Reprod Med. 1992;37:930–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Joesoef MR, Sumampouw H, Linnan M, et al. Douching and sexually transmitted diseases in pregnant women in Surabaya, Indonesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:115–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Perloff WH, Steinberger E. In vivo survival of spermatoza in cervical mucus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;88:439–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Funkhouser E, Pulley L, Lueschen G, et al. Douching beliefs and practices among black and white women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Lichtenstein B, Nansel TR. Women's douching practices and related attitudes: findings from four focus groups. Women Health. 2000;31:117–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Funkhouser E, Hayes TD, Vermund SH. Vaginal douching practices among women attending a university in the southern United States. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50:177–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Forrest KA, Washington AE, Daling JR, et al. Vaginal douching as a possible risk factor for pelvic inflammatory disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 1989;81:159–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Dan BB. Sex, lives, and chlamydia rates. (Editorial) JAMA. 1990;263:3191–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Ness R, Brooks-Nelson D. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women & health. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 369–80. [Google Scholar]

25. Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, et al. Douching and endometritis: results from the PID evaluation and clinical health (PEACH) study. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Miller HG, Cain VS, Rogers SM, et al. Correlates of sexually transmitted bacterial infections among U.S. women in 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:4–9. 23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Horowitz BJ, Mardh PA, editors. Vaginitis and vaginosis. Wiley-Liss; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

28. Schwebke JR. Vaginal infections. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women & health. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 352–60. [Google Scholar]

29. Newton ER, Piper JM, Shain RN, et al. Predictors of the vaginal microflora. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:845–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Pavlova SI, Tao L. In vitro inhibition of commercial douche products against vaginal microflora. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2000;8:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Juliano C, Piu L, Gavini E, et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of antiseptics against vaginal lactobacilli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:1166–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Onderdonk AB, Delaney ML, Hinkson PL, et al. Quantitative and qualitative effects of douche preparations on vaginal microflora. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Monif GR, Thompson JL, Stephens HD, et al. Quantitative and qualitative effects of povidone-iodine liquid and gel on the aerobic and anaerobic flora of the female genital tract. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:432–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Monif GR. The great douching debate: to douche, or not to douche. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:630–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Rajamanoharan S, Low N, Jones SB, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, ethnicity, and the use of genital cleaning agents: a case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:404–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Fleury FJ. Adult vaginitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1981;24:407–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Spiegel CA, Amsel R, Eschenbach D, et al. Anaerobic bacteria in nonspecific vaginitis. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Eschenbach DA, Davick PR, Williams BL, et al. Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:251–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Rabe LK, et al. The normal vaginal flora, H2O2-producing lactobacilli, and bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(suppl 4):S273–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Fiscella K. Racial disparities in preterm births. The role of urogenital infections. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:104–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Goldenberg RL, Klebanoff MA, Nugent R, et al. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1618–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Llahi-Camp JM, Rai R, Ison C, et al. Association of bacterial vaginosis with a history of second trimester miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1575–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Hawes SE, Hillier SL, Benedetti J, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli and acquisition of vaginal infections. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1058–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Bump RC, Buesching WJ., 3rd Bacterial vaginosis in virginal and sexually active adolescent females: evidence against exclusive sexual transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:935–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Schwebke JR, Richey CM, Weiss HL. Correlation of behaviors with microbiological changes in vaginal flora. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1632–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Hodoglugil NN, Aslan D, Bertan M. Intrauterine device use and some issues related to sexually transmitted disease screening and occurrence. Contraception. 2000;61:359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Faro S, Martens M, Maccato M, et al. Vaginal flora and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:470–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Soper DE, Brockwell NJ, Dalton HP, et al. Observations concerning the microbial etiology of acute salpingitis (with discussion) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1008–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Sweet RL. Role of bacterial vaginosis in pelvic inflammatory disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(suppl 2):S271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Hillier SL, Kiviat NB, Hawes SE, et al. Role of bacterial vaginosis-associated microorganisms in endometritis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:435–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Gravett MG, Nelson HP, DeRouen T, et al. Independent associations of bacterial vaginosis and Chlamydia trachomatis infection with adverse pregnancy outcome. JAMA. 1986;256:1899–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Martius J, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, et al. Relationships of vaginal Lactobacillus species, cervical Chlamydia trachomatis, and bacterial vaginosis to preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Lee ML, et al. Vaginal Bacteroides species are associated with an increased rate of preterm delivery among women in preterm labor. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Kurki T, Sivonen A, Renkonen OV, et al. Bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. McDonald HM, O'Loughlin JA, Jolley P, et al. Prenatal microbiological risk factors associated with preterm birth. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Riduan JM, Hillier SL, Utomo B, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and prematurity in Indonesia: association in early and late pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:175–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Holst E, Goffeng AR, Andersch B. Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal microorganisms in idiopathic premature labor and association with pregnancy outcome. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:176–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, et al. Abnormal bacterial colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late miscarriage. BMJ. 1994;308:295–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The preterm prediction study: significance of vaginal infections. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1231–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Bruce FC, Fiscella K, Kendrick JS. Vaginal douching and preterm birth: an intriguing hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2000;54:448–52. (Published erratum appears in Med Hypotheses 2000;54:859) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Hillier SL, Martius J, Krohn M, et al. A case-control study of chorioamnionic infection and histologic chorioamnionitis in prematurity. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:972–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, et al. Preterm labor associated with subclinical amniotic fluid infection and with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:229–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Silver HM, Sperling RS, St. Clair PJ, et al. Evidence relating bacterial vaginosis to intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:808–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Cassen E, et al. The role of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal bacteria in amniotic fluid infection in women in preterm labor with intact fetal membranes. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(suppl 2):S276–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, et al. Reduced incidence of preterm delivery with metronidazole and erythromycin in women with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1732–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Kekki M, Kurki T, Pelkonen J, et al. Vaginal clindamycin in preventing preterm birth and peripartal infections in asymptomatic women with bacterial vaginosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:643–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Kurkinen-Raty M, Vuopala S, Koskela M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vaginal clindamycin for early pregnancy bacterial vaginosis. BJOG. 2000;107:1427–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and why preterm prevention programs have failed. (Editorial) Am J Public Health. 1996;86:781–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Goldenberg RL, Vermund SH, Goepfert AR, et al. Choriodecidual inflammation: a potentially preventable cause of perinatal HIV-1 transmission? Lancet. 1998;352:1927–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Holzman C, Leventhal JM, Qiu H, et al. Factors linked to bacterial vaginosis in nonpregnant women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1664–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Fonck K, Kaul R, Keli F, et al. Sexually transmitted infections and vaginal douching in a population of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:271–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Royce RA, French JI, Savitz DA, et al. Vaginal douching, bacterial vaginosis, and preterm birth. (Abstract 574) Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:S161. [Google Scholar]

75. Stevens-Simon C, Jamison J, McGregor JA, et al. Racial variation in vaginal pH among healthy sexually active adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Brunham RC, Maclean IW, Binns B, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis: its role in tubal infertility. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1275–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Sellors JW, Mahony JB, Chernesky MA, et al. Tubal factor infertility: an association with prior chlamydial infection and asymptomatic salpingitis. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Kelver ME, Nagamani M. Chlamydial serology in women with tubal infertility. Int J Fertil. 1989;34:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Recommendations for the prevention and management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections, 1993. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42(RR12):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Tubal infertility: serologic relationship to past chlamydial and gonococcal infection. World Health Organization Task Force on the Prevention and Management of Infertility. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:71–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Chow JM, Yonekura ML, Richwald GA, et al. The association between Chlamydia trachomatis and ectopic pregnancy. A matched-pair, case-control study. JAMA. 1990;263:3164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Burstein G, Rompalo A. Chlamydia. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women & health. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 273–84. [Google Scholar]

83. Peters SE, Beck-Sague CM, Farshy CE, et al. Behaviors associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis: cervical infection among young women attending adolescent clinics. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Beck-Sague CM, Farshy CE, Jackson TK, et al. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis cervical infection by urine tests among adolescents clinics. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Stergachis A, Scholes D, Heidrich FE, et al. Selective screening for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in a primary care population of women. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:143–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Gresenguet G, Kreiss JK, Chapko MK, et al. HIV infection and vaginal douching in central Africa. AIDS. 1997;11:101–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Harrison HR, Costin M, Meder JB, et al. Cervical Chlamydia trachomatis infection in university women: relationship to history, contraception, ectopy, and cervicitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:244–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Louv WC, Austin H, Perlman J, et al. Oral contraceptive use and the risk of chlamydial and gonococcal infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Moss GB, Clemetson D, D'Costa L, et al. Association of cervical ectopy with heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: results of a study of couples in Nairobi, Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:588–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Critchlow CW, Wolner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, et al. Determinants of cervical ectopia and of cervicitis: age, oral contraception, specific cervical infection, smoking, and douching. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:534–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Jacobson DL, Peralta L, Farmer M, et al. Cervical ectopy and the transformation zone measured by computerized planimetry in adolescents. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Moscicki AB, Ma Y, Holland C, et al. Cervical ectopy in adolescent girls with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:865–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Soper DE, Brockwell NJ, Dalton HP, et al. Observations concerning the microbial etiology of acute salpingitis (with discussion) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1008–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Scaglione NJ. Bacterial vaginosis: current review with indications for asymptomatic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1210–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Jossens MO, Schachter J, Sweet RL. Risk factors associated with pelvic inflammatory disease of differing microbial etiologies. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:989–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Pletcher JR, Slap GB. Pelvic inflammatory disease. Pediatr Rev. 1998;19:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Washington AE, Katz P. Cost of and payment source for pelvic inflammatory disease. Trends and projections, 1983 through 2000. JAMA. 1991;266:2565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. 1998 guidelines for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR1):1–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Sweet RL. Role of bacterial vaginosis in pelvic inflammatory disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(suppl 2):S271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Ivey JB. The adolescent with pelvic inflammatory disease: assessment and management. Nurse Pract. 1997;22:78, 81–4, 87–8, passim. quiz 92-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Eschenbach DA, Harnisch JP, Holmes KK. Pathogenesis of acute pelvic inflammatory disease: role of contraception and other risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;128:838–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Neumann HH, DeCherney A. Douching and pelvic inflammatory disease. (Letter) N Engl J Med. 1976;295:789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Aral SO, Mosher WD, Cates W., Jr Self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease in the United States, 1988. JAMA. 1991;266:2570–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Scholes D, Daling JR, Stergachis A, et al. Vaginal douching as a risk factor for acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Quan M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: diagnosis and management. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1994;7:110–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Jossens MO, Eskenazi B, Schachter J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic inflammatory disease. A case control study. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23:239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Foxman B, Aral SO, Holmes KK. Interrelationships among douching practices, risky sexual practices, and history of self-reported sexually transmitted diseases in an urban population. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:90–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Hirst DV, Bluffs C. Dangers of improper vaginal douching. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1952;64:179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Grodstein F, Rothman KJ. Epidemiology of pelvic inflammatory disease. Epidemiology. 1994;5:234–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Paisarntantiwong R, Brockmann S, Clarke L, et al. The relationship of vaginal trichomoniasis and pelvic inflammatory disease among women colonized with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:344–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Mueller BA, Luz-Jimenez M, Daling JR, et al. Risk factors for tubal infertility. Influence of history of prior pelvic inflammatory disease. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Cates W, Jr, Wasserheit JN, Marchbanks PA. Pelvic inflammatory disease and tubal infertility: the preventable conditions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;709:179–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Baird DD, Strassmann BI. Women's fecundability and factors affecting it. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women & health. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 126–37. [Google Scholar]

114. Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Westrom L. Incidence, prevalence, and trends of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in industrialized countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:880–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Carr RJ, Evans P. Ectopic pregnancy. Prim Care. 2000;27:169–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Parazzini F, Tozzi L, Ferraroni M, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: an Italian case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:821–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Ankum WM, Mol BW, Van der Veen F, et al. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:1093–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Pisarska MD, Carson SA, Buster JE. Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 1998;351:1115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Chow WH, Daling JR, Weiss NS, et al. Vaginal douching as a potential risk factor for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:727–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Daling JR, Weiss NS, Schwartz SM, et al. Vaginal douching and the risk of tubal pregnancy. Epidemiology. 1991;2:40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Phillips RS, Tuomala RE, Feldblum PJ, et al. The effect of cigarette smoking, Chlamydia trachomatis infection, and vaginal douching on ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Kendrick JS, Atrash HK, Strauss LT, et al. Vaginal douching and the risk of ectopic pregnancy among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:991–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Bosch FX, Munoz N. Cervical cancer. In: Goldman MB, Hatch MC, editors. Women & health. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 932–41. [Google Scholar]

125. American Cancer Society What are key statistics about cancer of the cervix? Feb, 2000.

http://www3cancer.org/cancerinfo/load_c ... LISH#stats126. National Cancer Institute Cervical cancer backgrounder: facts and figures. Feb, 1999.

http://rex.nci.nih.gov/massmedia/backgr ... vical.html127. Haverkos H, Rohrer M, Pickworth W. The cause of invasive cervical cancer could be multifactorial. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54:54–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Graham S, Schotz W. Epidemiology of cancer of the cervix in Buffalo, New York. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979;63:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Peters RK, Thomas D, Hagan DG, et al. Risk factors for invasive cervical cancer among Latinas and non-Latinas in Los Angeles County. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:1063–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Brinton LA, Hamman RF, Huggins GR, et al. Sexual and reproductive risk factors for invasive squamous cell cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;79:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Herrero R, Brinton LA, Reeves WC, et al. Sexual behavior, venereal diseases, hygiene practices, and invasive cervical cancer in a high-risk population. Cancer. 1990;65:380–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Gardner JW, Schuman KL, Slattery ML, et al. Is vaginal douching related to cervical carcinoma? Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:368–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Slattery ML, Gardner JW. Risk factors for cervical carcinoma: does detection bias play a role? Epidemiology. 1991;2:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Stone KM, Zaidi A, Rosero-Bixby L, et al. Sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk of cervical cancer. Epidemiology. 1995;6:409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2:403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, et al. Non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS. 1993;7:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346:530–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

138. Cohen CR, Duerr A, Pruithithada N, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9:1093–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

139. Sewankambo N, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet. 1997;350:546–50. Published erratum appears in Lancet 1997;350:1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140. Royce RA, Thorp J, Granados JL, et al. Bacterial vaginosis associated with HIV infection in pregnant women from North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:382–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

141. Klebanoff SJ, Coombs RW. Viricidal effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus on human immunodeficiency virus type 1: possible role in heterosexual transmission. J Exp Med. 1991;174:289–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

142. Hill JA, Anderson DJ. Human vaginal leukocytes and the effects of vaginal fluid on lymphocyte and macrophage defense functions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:720–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143. Helfgott A, Eriksen N, Bundrick CM, et al. Vaginal infections in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:347–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

144. Tevi-Benissan C, Belec L, Levy M, et al. In vivo semen-associated pH neutralization of cervicovaginal secretions. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:367–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

145. Baird DD. The great douching debate: to douche, or not to douche. (Letter) Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:473–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

146. Osborne NG, Wright RC. Effect of preoperative scrub on the bacterial flora of the endocervix and vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;50:148–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

147. Beaton JH, Gibson F, Roland M. Short-term use of a medicated douche preparation in the symptomatic treatment of minor vaginal irritation, in some cases associated with infertility. Int J Fertil. 1984;29:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

148. Manzardo S, Girardello R, Pinzetta A, et al. Activity and tolerability of tetridamine vaginal lavage in rats and women. Boll Chim Farm. 1992;131:113–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

149. Vaginal douching Presented at the Nonprescription Drug Advisory Committee; Gaithersburg, Maryland. April 15, 1997; [Google Scholar]

150. Stray-Pedersen B, Bergan T, Hafstad A, et al. Vaginal disinfection with chlorhexidine during childbirth. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12:245–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

151. Dykes AK, Christensen KK, Christensen P, et al. Chlorhexidine for prevention of neonatal colonization with group B streptococci. II. Chlorhexidine concentrations and recovery of group B streptococci following vaginal washing in pregnant women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1983;16:167–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

152. Sweeten KM, Eriksen NL, Blanco JD. Chlorhexidine versus sterile water vaginal wash during labor to prevent peripartum infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:426–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

153. Taha TE, Biggar RJ, Broadhead RL, et al. Effect of cleansing the birth canal with antiseptic solution on maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality in Malawi: clinical trial (with discussion) BMJ. 1997;315:216–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

154. Gaillard P, Mwanyumba F, Verhofstede C, et al. Vaginal lavage with chlorhexidine during labour to reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission: clinical trial in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS. 2001;15:389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

155. Biggar RJ, Miotti PG, Taha TE, et al. Perinatal intervention trial in Africa: effect of a birth canal cleansing intervention to prevent HIV transmission. Lancet. 1996;347:1647–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

156. Obaidullah M. A study to determine the effect of Betadine Vaginal Cleansing Kit on cervical flora after insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device. J Int Med Res. 1981;9:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

157. Walker MA. Pneumoperitoneum following a douche. J Kansas Med Soc. 1942;43:55. [Google Scholar]

158. Natenshon AL. Extreme shock and near death resulting from a douche. West J Surg. 1947;55:187–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

159. Forbes G. Air embolism as a complication of vaginal douching in pregnancy. BMJ. 1944;2:529–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

160. Czerwinski BS. Adult feminine hygiene practices. Appl Nurs Res. 1996;9:123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

161. Majeroni BA. Douching frequency. (Letter) J Fam Pract. 1997;45:168–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

162. Safran M, Braverman LE. Effect of chronic douching with polyvinylpyrrolidone-iodine on iodine absorption and thyroid function. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

163. Udoma EJ, Umoh MS, Udosen EO. Recto-vaginal fistula following coitus: an aftermath of vaginal douching with aluminium potassium sulphate dodecahydrate (potassium alum) Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

164. Wright FW, Lumsden K. Recurrent pneumoperitoneum due to jejunal diverticulosis. With a review of the causes of spontaneous pneumoperitoneum. Clin Radiol. 1975;26:327–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

165. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Technical bulletin—vaginitis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

166. Novitt-Moreno A. American Medical Association health insight: vaginitis. Oct, 1999.

http://www.ama-assn.org/insight/h_focus ... ginit2.htm167. Kendrick JS, Atrash HK, Strauss LT, et al. Summary: vaginal douching and the risk of ectopic pregnancy among black women. 1997.

http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/drh/rem_douch.htm [PubMed]

168. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted disease facts—bacterial vaginosis. Sep, 2000.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/dstd/Fact_Sheets/FactsBV.htm169. Pelvic inflammatory disease: guidelines for prevention and management. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40(RR5):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

170. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2000. Family planning methods and practice: Africa. [Google Scholar]

171. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Vaginitis. Apr, 2000.

http://15640883/publications/pubs/vag5htm172. National Institutes of Health. Baird DD, Voight LF, et al. NIH study: among women who want to get pregnant, douching may delay conception. Oct, 1996.

http://www.niehs.nih.gov/oc/news/douche.htm173. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Fact sheet—pelvic inflammatory disease. Jul, 1998.

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/stdpid.htm174. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Fact sheet—an introduction to sexually transmitted diseases. Jul, 1999.

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/stdinfo.htm175. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Fact sheet—vaginitis due to vaginal infections. Jun, 1998.

http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/stdvag.htm176. National Women's Health Information Center Douching. Dec, 2000.

http://www.4woman.gov/faq/douching.htm