by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/9/20

Most of these miners were Mexican and Eastern European immigrants, others were Mexican-Americans....

From the late 1880s, Bisbee was defined as a “white man’s camp,” which originally meant the exclusion of Chinese laborers. Then the term referred to the exclusion of other non-white laborers, including “Mexicans,” a term used by whites to mean both Mexican immigrants and Hispanics native to Arizona.

“Mexicans” had been allowed to live and work in Bisbee, but only as menial laborers -- even when they did the same jobs as “white” men, they were paid far less. Then immigrants from Serbia and Italy started coming to work the mines in the early 1900s, which complicated the “white”/”Mexican” distinction. They were described as “foreign labor” and occupied a sort of in-between status in the hierarchy there.

The racial hierarchy of miners was underscored by a pervasive “family wage ideology.” Real men were supposed to make enough money to take care of their whole family. But in the eyes of both white workers and the copper company, “Mexican” workers were not real men. “Anglo workers and managers infantilized and feminized Mexican workers to reinforce their exclusion from the family wage and the American standard of living.”...

The workers, however, had the misfortune of striking during wartime. Militant patriotism was at a fever pitch. The man in charge of the roundup and deportation, Sheriff Wheeler, used the wartime emergency as an excuse to rid the town of “foreigners.” But he had another motive, too, which Benton-Cohen describes as maintaining “Bisbee’s most precious social boundaries—those that separated working class Mexican men from ‘white women.'” As Wheeler himself described it, he was protecting white womanhood and “pure Americanism itself” by removing the foreigners (80% of the Bisbee Deportees were foreign-born; of these, 40% were Slavic).

-- The Bisbee Deportations, by Matthew Wills

Bisbee Deportation

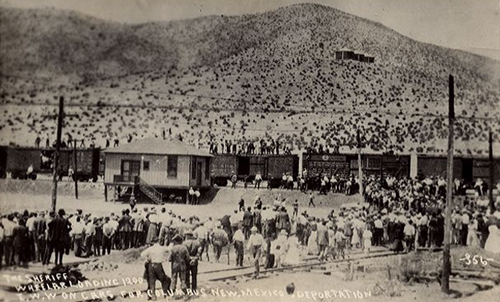

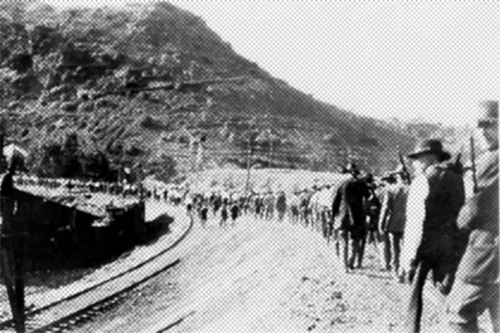

Striking miners and others being deported from Bisbee on the morning of July 12, 1917. The men are boarding the cattle cars provided by the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad.

Date: July 12, 1917

Location: Bisbee, Arizona; Jerome, Arizona

Goals: Union organizing

Methods: Strikes, protest, demonstrations

Resulted in: ~1,300 miners deported from Arizona

Parties to the civil conflict: International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers; Industrial Workers of the World / Phelps Dodge Corporation; Sherriff's deputies

Lead figures: Charles Moyer / Walter S. Douglas; Harry Wheeler

Number: 2,000 protesters / 2,200

Arrests, etc

Deaths: 1 / Deaths: 1

Arrests: 1,300+

The Bisbee Deportation was the illegal kidnapping and deportation of about 1,300 striking mine workers, their supporters, and citizen bystanders by 2,000 members of a deputized posse, who arrested these people beginning on July 12, 1917. The action was orchestrated by Phelps Dodge, the major mining company in the area, which provided lists of workers and others who were to be arrested in Bisbee, Arizona, to the Cochise County sheriff, Harry C. Wheeler. These workers were arrested and held at a local baseball park before being loaded onto cattle cars and deported 200 miles (320 km) to Tres Hermanas in New Mexico. The 16-hour journey was through desert without food and with little water. Once unloaded, the deportees, most without money or transportation, were warned against returning to Bisbee.

As Phelps Dodge, in collusion with the sheriff, had closed down access to outside communications, it was some time before the story was reported. The company presented their action as reducing threats to United States interests in World War I in Europe. The Governor of New Mexico, in consultation with President Woodrow Wilson, provided temporary housing for the deportees. A presidential mediation commission investigated the actions in November 1917, and in its final report, described the deportation as "wholly illegal and without authority in law, either State or Federal."[1] Nevertheless, no individual, company, or agency was ever convicted in connection with the deportations.

Background

In 1917, the Phelps Dodge Corporation owned a number of copper and other mines in Arizona. Mining conditions in the region were difficult, and working conditions (including mine safety, pay, and camp living conditions) were extremely poor. Discrimination against Mexican American and immigrant workers by European-American supervisors was routine and extensive. During the winter of 1915–6, a successful if bitter four-month strike in the Clifton-Morenci district led to widespread discontent and unionization among miners in the state.[2][3]

But, the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW) and its president, Charles Moyer, did little to support the nascent union movement. Between February and May 1917, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) stepped in and began signing up several hundred miners as members. The IWW formed Metal Mine Workers Union No. 800. Although Local 800 counted more than 1,000 members, only about 400 paid dues.[3][4][5]

Strike

Panoramic view of Bisbee, Arizona, in 1916, shortly before the Bisbee Deportation

The town of Bisbee had about 8,000 citizens in 1917. The city was dominated by Phelps Dodge (which owned the Copper Queen Mine) and two other mining firms: the Calumet and Arizona Co., and the Shattuck Arizona Co. Phelps Dodge was by far the largest company and employer in the area; it also owned the largest hotel in town, the hospital, the only department store, the town library, and the town newspaper, the Bisbee Daily Review.[6][7]

In May 1917, IWW Local 800 presented a list of demands to Phelps Dodge. They asked for an end to physical examinations after shifts (used by the mine owners to counter theft), having two workers on each drilling machine, two men working the ore elevators, an end to blasting while men were in the mine, an end to the bonus system,[a] no more assignment of construction work to miners,[ b] replacement of the sliding scale of wages with a $6.00 per day shift rate, and no discrimination against union members. The company refused all the demands.[3][4]

IWW Local 800 called a strike to begin on June 26, 1917. When the strike occurred as scheduled, not only the miners at Phelps Dodge, but also those at other mines walked out. More than 3,000 miners—about 85 percent of all mine workers in Bisbee—went on strike.[4][5][6]

Although the strike was peaceful, local authorities immediately asked for federal troops to break the strike. Cochise County Sheriff Harry Wheeler set up his headquarters in Bisbee on the first day of the strike. On July 2, Wheeler asked Republican Governor Thomas Edward Campbell to request federal troops, suggesting the strike threatened US war interests: "The whole thing appears to be pro-German and anti-American."[8] Campbell quickly telegraphed the White House and made the request, but President Woodrow Wilson declined to send in the Army. He appointed former Arizona Governor George W. P. Hunt as a mediator.[4][5][6]

The president of Phelps Dodge at the time was Walter S. Douglas. He was the son of Dr. James Douglas, developer of the Copper Queen mine and a member of the board of directors of the Phelps Dodge Corporation. Douglas was a political opponent of Governor Hunt and had virulently attacked him for refusing, as governor, to send the state militia to suppress strikes in the mining industry. Douglas was also president of the American Mining Congress, an employer association. He had won office by vowing to break every union in every mine and restore the open shop. Determined to keep Bisbee free of IWW influence, in 1916, Douglas established a Citizens' Protective League, composed of business leaders and middle-class local residents. He also organized a Workmens' Loyalty League, some of whose members were IUMMSW miners.[3][4][9]

Deportations

Jerome

On July 5, 1917, an IWW local in Jerome, Arizona, struck Phelps Dodge. Douglas ordered his mine superintendents to remove the miners from the town, in what became known as the Jerome Deportation. Mine supervisors, joined by 250 local businessmen and members of the IUMMSW,[10] began rounding up suspected IWW members at dawn on July 10. More than 100 men were abducted by these vigilantes and held in the county jail (with the cooperation of the Yavapai County sheriff). Later that day, 67 men were deported by train to Needles, California, and ordered not to return. When the IWW protested to Governor Campbell, he declared that the IWW had "threatened" the governor.[4]

Bisbee

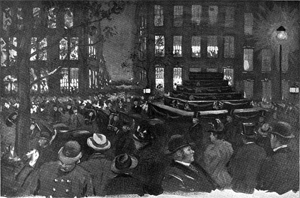

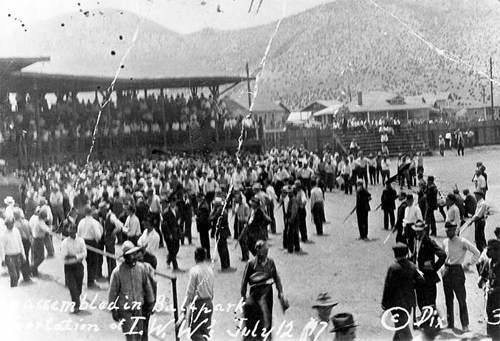

Striking miners and others rounded up by the armed posse on July 12, 1917, sit in the bleachers in Warren Ballpark. Armed members of the posse patrol the infield.

The Jerome Deportation proved to be a test run for Phelps Dodge, which ordered the same plan, but larger in scale, in Bisbee.

On July 11, 1917, Sheriff Wheeler met with Phelps Dodge corporate executives to plan the deportation of striking miners. Some 2,200 men from Bisbee and the nearby town of Douglas were recruited and deputized as a posse— one of the largest posses ever assembled. Phelps Dodge officials also met with executives of the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad, who agreed to provide rail transportation for any deportees. The morning of July 12, the Bisbee Daily Review carried a notice announcing that:

...a Sheriff's posse of 1,200 men in Bisbee and 1,000 men in Douglas, all loyal Americans, [had formed] for the purpose of arresting on the charges of vagrancy, treason, and of being disturbers of the peace of Cochise County all those strange men who have congregated here from other parts and sections for the purpose of harassing and intimidating all men who desire to pursue their daily toil.[11]

A similar notice was posted throughout the town on fence posts, telephone poles and walls.

At 4:00 a.m., July 12, 1917, the 2,200 deputies dispersed through the town of Bisbee and took up their planned positions. Each wore a white armband for identification, and carried a list of the men on strike. At 6:30 a.m., the deputies moved through town and arrested every man on their list, as well as any man who refused to work in the mines. Several men who owned local grocery stores were also arrested. In the process, the deputies took cash from the registers and all the goods they could carry. They arrested many male citizens of the town, seemingly at random, and anyone who had voiced support for the strike or the IWW. Two men died: one was a deputy shot by a miner he had tried to arrest, and the other was the miner (shot dead by three other deputies moments later).[3][4][5][6]

At 7:30 a.m., the 2,000 arrested men were assembled in front of the Bisbee Post Office and marched two miles (3 km) to Warren Ballpark. Sheriff Wheeler oversaw the march from a car outfitted with a loaded Marlin 7.62 mm belt-fed machine gun. At the baseball field, the arrestees were told that if they denounced the IWW and went back to work, they would be freed. Only men who were not IWW members or organizers were given this choice. About 700 men agreed to these terms, while the rest sang, jeered or shouted profanities.[3][4][5][6]

At 11:00 a.m., the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad brought 23 cattle cars to Bisbee. The posse deputies forced the remaining 1,286 arrestees at gunpoint to board the cars, many of which had more than three inches (76 mm) of manure on the floor. Although temperatures were in the mid-90s Fahrenheit,[12] (mid-30s Celsius), no water had been provided to the men since the arrests began at dawn.[3][4][5][6]

The train stopped 10 miles (16 km) east of Douglas to take on water, some of which was provided to the deportees in the packed cars. Deputies manned two machine guns from nearby hilltops to guard the train, while another 200 armed men patrolled the tracks. The train continued to Columbus, New Mexico (about 175 miles (282 km) away), arriving at about 9:30 p.m. Initially prevented from unloading at Columbus, the train slowly traveled west another 20 miles (32 km) to Hermanas, not stopping until 3:00 a.m.[3][4][5][6][13]

During the Bisbee Deportation, Phelps Dodge executives seized control of the telegraph and telephones to prevent news of the arrests and expulsion from being reported. Company executives refused to let Western Union send wires out of town, and stopped Associated Press reporters from filing stories.[14] News of the Bisbee Deportation was made known only after an IWW attorney, who met the train in Hermanas, issued a press release.[4]

With 1,300 penniless men in Hermanas, the Luna County sheriff worriedly wired the Governor of New Mexico for instructions. Republican Governor Washington Ellsworth Lindsey said the men should be treated humanely and fed; he urgently contacted President Wilson and asked for assistance. Wilson ordered U.S. Army troops to escort the men to Columbus, New Mexico. The deportees were housed in tents originally intended for use by Mexican refugees, who had fled across the border to the United States to escape the Mexican Army's Pancho Villa Expedition. The men were allowed to stay in the camp for two months until September 17, 1917.[3][4][5][6]

Aftermath

From the day of the deportations until November 1917, the Citizens' Protective League ruled Bisbee. Based in a building owned by the copper companies, its representatives interrogated residents about their political beliefs with respect to unions and the war, determining who could work or obtain a draft deferment. Sheriff Wheeler established guards at all entrances to Bisbee and Douglas. Anyone seeking to exit or enter the town over the next several months had to have a "passport" issued by Wheeler. Any adult male in town who was not known to the sheriff's men was brought before a secret sheriff's kangaroo court. Hundreds of citizens were tried, and most of them were deported and threatened with lynching if they returned. Even long-time citizens of Bisbee were deported by this "court".[3][4][5][6]

When ordered to cease these activities by the Arizona Attorney General, Wheeler tried to explain his actions. Asked what law supported his actions, he answered:

I have no statute that I had in mind. Perhaps everything that I did wasn't legal....It became a question of 'Are you American, or are you not?'" He told the Attorney General: "I would repeat the operation any time I find my own people endangered by a mob composed of eighty percent aliens and enemies of my Government."[15]

These actions took place during a period in the early 20th century when attacks by anarchists and labor unrest and violence erupted in numerous American cities and industries. Many native-born Americans were worried about such actions, attributing the unrest to the high numbers of immigrants, rather than to the poor working conditions in many industries. As a result, national press reaction to the Bisbee Deportation was muted. Although many newspapers carried stories about the event, most of them editorialized that the workers "must have" been violent, and therefore "gotten what they deserved", thus criminalizing the victims. Some major papers said that Sheriff Wheeler had gone too far, but declared that he should have imprisoned the miners rather than deported them.[3][4][5][6] The New York Times criticized the violence on the part of the mine owners and suggested that mass arrests "on vagrancy charges" would have been appropriate.[16] Former President Theodore Roosevelt said that "no human being in his senses doubts that the men deported from Bisbee were bent on destruction and murder."[15]

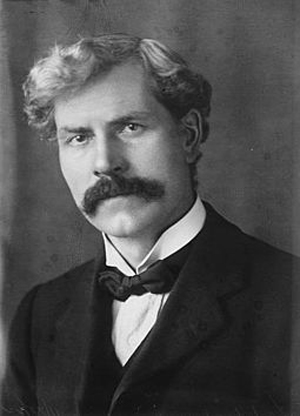

Then Secretary of Labor William Wilson

The men deported from Bisbee pleaded with President Wilson for protection and permission to return to their homes. In October 1917, Wilson appointed a commission of five individuals to investigate labor disputes in Arizona. They were led by Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson (with support from Assistant Secretary of Labor Felix Frankfurter, future Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court). The commission heard testimony during the first five days of November 1917.[3][4][5][6] In its final report, issued on November 6, 1917, the commission denounced the Bisbee Deportation. "The deportation was wholly illegal and without authority in law, either State or Federal," the commissioners wrote.[1]

Prosecution

On May 15, 1918, the U.S. Department of Justice ordered the arrest of 21 Phelps Dodge executives, including some from the Calumet and Arizona Co., and several elected leaders and law enforcement officers from Bisbee and Cochise Counties. The arrestees included Walter S. Douglas. Sheriff Wheeler was not arrested because he was by then serving in France with the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.

A pre-trial motion by the defense led a federal district court to release the 21 men on the grounds that no federal laws had been violated.[3][4][5][6] The Justice Department appealed, but in United States v. Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281 (1920), Chief Justice Edward Douglass White wrote for an 8-to-1 majority that the U.S. Constitution did not empower the federal government to enforce the rights of the deportees. Rather, it "necessarily assumed the continued possession by the states of the reserved power to deal with free residence, ingress and egress." Only in a case of "state discriminatory action" would the federal government have a role to play.[17]

Arizona officials never initiated criminal proceedings in state court against those responsible for the deportation of workers and their lost wages and other losses. Some workers filed civil suits, but in the first case the jury determined that the deportations represented good public policy and refused to grant relief. Most of the other suits were quietly dropped, although a few workers received payments in the range of $500 to $1,250.[3][4][5][6]

The Bisbee Deportations were later used by some proponents as an argument in favor of stronger laws against unpopular speech. Such laws would be justified as empowering the government to suppress disloyal speech and activity, and remove the need for citizens groups to take actions the government could not. During World War I, the federal government used the Sedition Act of 1918 to prosecute people for statements in opposition to the war.

At the end of the conflict, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and others advocated for a peacetime equivalent of the Sedition Act, using the Bisbee events as a justification. They claimed that the only reason the company representatives and local law enforcement had taken the law into their own hands was that the government lacked the power to suppress radical sentiment directly. If the government were armed with appropriate legislation and the threat of long prison terms, private citizens would not feel the need to act. Writing in 1920, Harvard Professor Zechariah Chafee mocked that view: "Doubtless some governmental action was required to protect pacifists and extreme radicals from mob violence, but incarceration for a period of twenty years seems a very queer kind of protection."[18]

Effects

The later history of American deportations of alleged radicals and other undesirables from the country did not follow the precedent of Bisbee and Jerome, which were considered vigilante actions by private citizens. Instead, later deportations were authorized by law and executed by government agents. These actions were criticized by contemporaries at the time on the basis of public policy and the US Constitution, as well as extensively by later analysts. Each case has involved discriminatory actions against ethnic minorities (and sometimes immigrants).

The most notable have included the following:

• deportation from the United States of supposed foreign anarchists during the Red Scare of 1919–20;

• mass deportations of up to 2 million Mexicans and Mexican-American workers (the latter citizens of the United States) between 1929 and 1936, during the Great Depression;[19]

• relocation and internment of 120,000 Japanese national and Japanese Americans to camps during World War II, causing them extensive losses of jobs and property; and

• 1954 removal by the Immigration and Naturalization Service of approximately a million Mexican nationals living in the U.S. without the legal right to do so. Many Mexican workers had been recruited during the war years, but in the postwar period, the US did not want them competing with American workers. In what is known as Operation Wetback, several hundred U.S. citizens were also deported by mistake, because of lack of due process.[20]

See also

• Anti-union violence

• Company town

• Freedom of movement under United States law

• Institutional racism

• Bisbee '17, 2018 film of the events

Notes

1. Under the bonus system, miners were paid more money not only for mining more ore, but for mining high-quality ore. Since only a few veins were of the highest-quality ore, assignment to these veins was very important. Mine supervisors routinely discriminated and played favorites among the miners when assigning the high-grade veins.

2. Construction work was unpaid.

References

1. eport on the Bisbee Deportations. Made by the President's Mediation Commission to the President of the United States.Bisbee, Arizona. November 6, 1917.

2. Kluger, James R. The Clifton-Morenci Strike: Labor Difficulty in Arizona, 1915–1916. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8165-0267-6

3. Jensen, Vernon H. Heritage of Conflict: Labor Relations in the Nonferrous Metals Industry up to 1930.Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1950.

4. Foner, Philip S. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918. New York: International Publishers, 1987. Cloth ISBN 0-7178-0638-3; Paperback ISBN 0-7178-0627-8

5. Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Abridged ed. Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2000. ISBN 0-252-06905-6

6. Byrkit, James. "The Bisbee Deportation." In American Labor in the Southwest. James C. Foster, ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1982. ISBN 0-8165-0741-4

7. Cleland, Robert Glass. A History of Phelps Dodge, 1834–1950. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952.

8. Christopher Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (NY: Oxford University Press, 2008), 126

9. Lindquist, John H. "The Jerome Deportation of 1917", Arizona and the West, Autumn 1969

10. It was not uncommon for unions in the first half of the 20th century to act as strikebreakers against other unions. The IUMMSW viewed the IWW as "not a real union" and often worked to break its strikes. See Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918, 1987, and Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World, 2000.

11. Quoted in Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 7: Labor and World War I, 1914–1918, 1987, p. 270.

12. Lindquist, John H. and Fraser, James. "A Sociological Interpretation of the Bisbee Deportation." Pacific Historical Review. 37:4 (November 1968).

13. Emery, Ken. "Wobbly Justice". Desert Exposure. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

14. "Report of a Censorship, Military Movements in Arizona Are Hidden," New York Times, July 13, 1917; "Arizona Sheriff Ships 1,100 I.W.W.'s Out In Cattle Cars," New York Times, July 13, 1917; "Not An Army Censorship, Phelps-Dodge Officials Said to Have Tied Up Bisbee Wires," New York Times, July 14, 1917.

15. Capozzola, 128

16. Capozzola, 129

17. Pratt, Jr., Walter F. The Supreme Court under Edward Douglass White, 1910–1921 Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1999, 257–8. ISBN 1-57003-309-9; FindLaw: U. S. v. Wheeler, 254 U.S. 281 (1920), accessed April 22, 2010. In 1966, when the Supreme Court considered a "right to travel" in United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966), Justice Potter Stewart devoted a footnote to dismissing Wheeler as precedent because "the right of interstate travel was...not directly involved" in the earlier case. FindLaw: United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 759, n. 16, accessed April 22, 2010

18. Zechariah Chafee, Jr., Freedom of Speech (NY: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920), 45–46.

19. McKay, Robert R. "The Federal Deportation Campaign in Texas: Mexican Deportation from the Lower Rio Grande Valley during the Great Depression," Borderlands Journal, Fall 1981

20. García, Juan Ramon, Operation Wetback: The Mass Deportation of Mexican Undocumented Workers in 1954 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1980), ISBN 0-313-21353-4

Further reading

• Leslie Marcy, "The Eleven Hundred Exiled Copper Miners," International Socialist Review, vol. 18, no. 3 (September 1917), pp. 160–162.

External links

• "Wobbly Justice" by Ken Emery in Desert Exposure, July 2007

• Bisbee Deportation online exhibit at the Library of the University of Arizona

• Video on Bisbee Deportation of 1917 Case, Jacob, and Sharlene Grant (First Place National History Day Competition)

• University of Arizona Archives Online

*************************************

The Bisbee Deportations

by Matthew Wills

JSTOR Daily

August 17, 2018

According to one scholar, the 1917 deportation in Bisbee, AZ wasn’t “about labor relations or race or gender: it was about all of them.”

Workers forced out of Bisbee, AZ at gunpoint, 1917. via Wikimedia Commons

On July 12th, 1917 in Bisbee, Arizona, over a thousand striking copper miners -- along with regular townsfolk like restaurant owners, carpenters, and exactly one lawyer -- were rounded up at gun-point, herded into boxcars, and taken two hundreds miles into the desert. A new movie, Bisbee ’17, opening next month, tells the story anew.

The miners were left out in the desert to fend for themselves, until a nearby army camp rescued them. Few of them ever returned to Bisbee. Most of these miners were Mexican and Eastern European immigrants, others were Mexican-Americans. Although not strictly a deportation, since they weren’t sent across any national border, the action became known as the Bisbee Deportation.

Historian Katherine Benton-Cohen writes that this event has been looked at through many lenses, but she argues that it wasn’t “about labor relations or race or gender: it was about all of them.”

“White Man’s Camp”

From the late 1880s, Bisbee was defined as a “white man’s camp,” which originally meant the exclusion of Chinese laborers. Then the term referred to the exclusion of other non-white laborers, including “Mexicans,” a term used by whites to mean both Mexican immigrants and Hispanics native to Arizona.

“Mexicans” had been allowed to live and work in Bisbee, but only as menial laborers -- even when they did the same jobs as “white” men, they were paid far less. Then immigrants from Serbia and Italy started coming to work the mines in the early 1900s, which complicated the “white”/”Mexican” distinction. They were described as “foreign labor” and occupied a sort of in-between status in the hierarchy there.

Real Men & The Family Wage

The racial hierarchy of miners was underscored by a pervasive “family wage ideology.” Real men were supposed to make enough money to take care of their whole family. But in the eyes of both white workers and the copper company, “Mexican” workers were not real men. “Anglo workers and managers infantilized and feminized Mexican workers to reinforce their exclusion from the family wage and the American standard of living.”

Unsurprisingly, these non-white workers rebelled against these views, as well the dual wage system that paid them less, during the 1917 strike in Bisbee. Benton-Cohen describes the strike as a “vivid assertion of their own manly identities,” an effort to end the “social compact of the white man’s camp, one that denied them full male economic and social citizenship.”

The workers, however, had the misfortune of striking during wartime. Militant patriotism was at a fever pitch. The man in charge of the roundup and deportation, Sheriff Wheeler, used the wartime emergency as an excuse to rid the town of “foreigners.” But he had another motive, too, which Benton-Cohen describes as maintaining “Bisbee’s most precious social boundaries—those that separated working class Mexican men from ‘white women.'” As Wheeler himself described it, he was protecting white womanhood and “pure Americanism itself” by removing the foreigners (80% of the Bisbee Deportees were foreign-born; of these, 40% were Slavic).

Benton-Cohen concludes by noting that her “emphasis on the role of masculinity—something seemingly natural but never stable—highlights the connections between gender, race, family, labor, and national identity.” And helps us understand a shameful incident with disturbing contemporary echoes.

*************************************

The Bisbee Deportation of 1917

by Sheila Bonnand

University of Arizona

1997

Overview

"How it could have happened in a civilized country I'll never know. This is the only country it could have happened in. As far as we're concerned, we're still on strike!"

~ Fred Watson*

The Bisbee Deportation was still fresh in Fred Watson's mind when interviewed 60 years later. This is not surprising, because on July 12, 1917, Watson and 1,185 other men were herded into filthy boxcars by an armed vigilante force in Bisbee, Arizona, and abandoned across the New Mexico border. The Bisbee Deportation of 1917 was not only a pivotal event in Arizona's labor history, but one that had an effect on labor activities throughout the country. What led to this course of action by the Bisbee authorities?

Arizona in the early 1900s was home to huge copper mining operations. The managers and engineers controlling these mines answered primarily to eastern stockholders. During World War I, the price of copper reached unprecedented heights and the companies reaped enormous profits. By March of 1917, copper sold for $.37 a pound; it had been $.13 1/2 at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. With five thousand miners working around the clock, Bisbee was booming.

To maintain high production levels, the pool of miners was increased from an influx of southern European immigrants. Although the mining companies paid relatively high wages, working conditions for miners were no better than before the copper market crash in 1907-1908. Furthermore, the inflation caused by World War I increased living expenses and eroded any gains the miners had realized in salaries.

The mining companies controlled Bisbee, not only because they were the primary employers but because local businesses depended heavily on the mines and miners to survive. Even the local newspaper was owned by one of the major mining companies, Phelps Dodge.

Prior to 1917, union activity had repeatedly been stifled. Between 1906 and 1907, for example, about 1,200 men were fired for for supporting a union. Conversely, the Bisbee Industrial Association, an alliance that was pro-company and anti-union, was easily organized around the same time. Finally, in 1916, the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter (formerly the Western Federation of Miners) successfully enrolled 1,800 miners.

The Industrial Workers of the World's (I.W.W.) presence in Arizona was also increasing. Founded in 1905, the I.W.W. never recruited more than five percent of the trade unionists in the country, but many others were exposed to its ideas. Some of the I.W.W.'s tactics, such as advocating slowdowns and sabotage, were of great concern to the controlling interests. In addition, the I.W.W. adopted two successful recruiting practices. They actively recruited miners from minority groups. As a result, the IWW was particularly successful recruiting Bisbee's Mexican workers, who were routinely given lower paying jobs outside of the mine. The I.W.W. was also successful recruiting southern European immigrants, who were allowed in the mines but given lower paying jobs.

On June 24, 1917, the I.W.W. presented the Bisbee mining companies with a list of demands. These demands included improvements to safety and working conditions, such as requiring two men on each machine and an end to blasting in the mines during shifts. Demands were also made to end discrimination against members of labor organizations and the unequal treatment of foreign and minority workers. Furthermore, the unions wanted a flat wage system to replace sliding scales tied to the market price of copper. The copper companies refused all I.W.W. demands, using the war effort as justification. As a result, a strike was called, and by June 27 roughly half of the Bisbee work force was on strike.

Tensions heightened when rumors spread asserting that the unions had been infiltrated by pro-Germans. Another rumor suggested that weapons and dynamite were cached around Bisbee for sabotage. The Citizen's Protective League, an anti-union organization formed during a previous labor dispute, was resurrected by local businessmen and put under the control of Sheriff Harry Wheeler. A group of miners loyal to the mining companies also formed the Workman's Loyalty League. On July 11, secret meetings of these two so-called "vigilante groups" were held to discuss ways to deal with the strike and the strikers.

The next day, starting at 2:00 a.m., calls were made to Loyalty Leaguers as far away as Douglas, Arizona. By 5:00 a. m., about 2,000 deputies assembled. All wore white armbands to distinguish them from other mining workers. No federal or state officials were notified of the vigilantes' plans. The Western Union telegraph office was seized, preventing any communication to the town.

At 6:30 a. m., Sheriff Harry Wheeler gave orders to begin the roundup. Throughout Bisbee, men were roused from their beds, their houses, and the streets. Though armed, the vigilantes were instructed to avoid violence. However, reports of beatings, robberies, vandalism, and abuse of women later surfaced.

Two men died during the roundup. James Brew shot Loyalty Leaguer, Orson McRae, after warning McRae he would shoot anyone who attempted to take him. Brew was in turn shot and killed by men accompanying McRae.

The vigilantes rounded up over 1,000 men, many of whom were not strikers -- or even miners -- and marched them two miles to the Warren Ballpark. There they were surrounded by armed Loyalty Leaguers and urged to quit the strike. Anyone willing to put on a white armband was released. At 11:00 a. m. a train arrived, and 1,186 men were loaded aboard boxcars inches deep in manure. Also boarding were 186 armed guards; a machine gun was mounted on the top of the train. The train traveled from Bisbee to Columbus, New Mexico, where it was turned back because there were no accommodations for so many men. On its return trip the train stopped at Hermanas, New Mexico, where the men were abandoned. A later train brought water and food rations, but the men were left without shelter until July 14th when U.S. troops arrived. The troops escorted the men to facilities in Columbus. Many were detained for several months.

Meanwhile, Bisbee authorities mounted guards on all roads into town to insure that no deportees returned and to prevent new "troublemakers" from entering. A kangaroo court was also established to try other people deemed disloyal to mining interests. These people also faced deportation.

Several months after the deportation, President Woodrow Wilson set up the Federal Mediation Commission to investigate the Bisbee Deportation. The Commission discovered that no federal law applied. It referred the issue to the State of Arizona while recommending that such events be made criminal by federal statute. They did hold that the copper companies were at fault in the deportation, not the I.W.W.

The State of Arizona took no action against the copper companies. Approximately 300 deportees brought civil suits against the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and the copper companies. None of these suits came to trial because of out-of-court settlements. Suits were also filed in state court against 224 vigilantes. Sadly, the only suit brought to trial ended in a "not guilty" verdict. The rest of the cases were dismissed.

Although efforts to organize pro-labor unions in Bisbee were crushed in 1917, the Deportation boosted I.W.W. efforts across the country.

To read more about Bisbee, the deportation, or the I.W.W., refer to the following sources or to those on the Resources page.

Sources

Lynn R Bailey, Bisbee, Queen of the Copper Camps (Westernlore Press, 1983).

Annie M. Cox, History of Bisbee, 1877 to 1937. (University of Arizona, 1938).

Rob E. Hanson The Great Bisbee I.W.W. Deportation of July 12, 1917 (Signature Press, 1989).

* Fred Watson, "Still on Strike! Recollections of a Bisbee Deportee" Journal of Arizona History 18 (Summer 1977): 171-184.