Part 3 of 3

Leadership

Leaders of the Labour Party since 1906Main article: Leader of the Labour Party (UK)

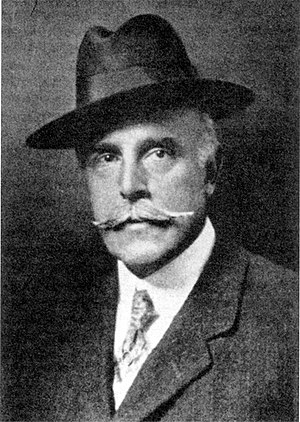

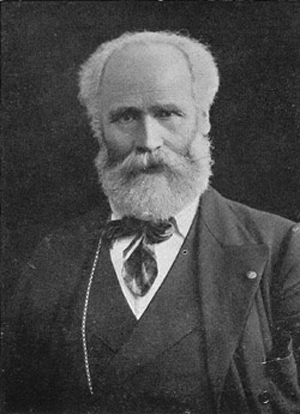

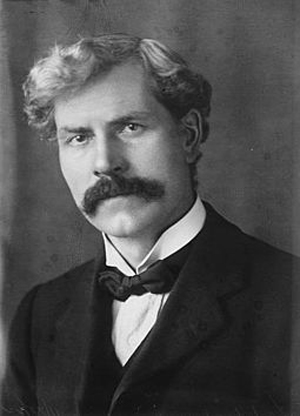

• Keir Hardie (1906–1908)

• Arthur Henderson (1908–1910)

• George Nicoll Barnes (1910–1911)

• Ramsay MacDonald (1911–1914)

• Arthur Henderson (1914–1917)

• William Adamson (1917–1921)

• John Robert Clynes (1921–1922)

• Ramsay MacDonald (1922–1931)

• Arthur Henderson (1931–1932)

• George Lansbury (1932–1935)

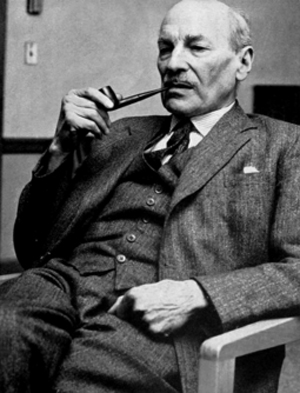

• Clement Attlee (1935–1955)

• Hugh Gaitskell (1955–1963)

o George Brown (1963; acting)

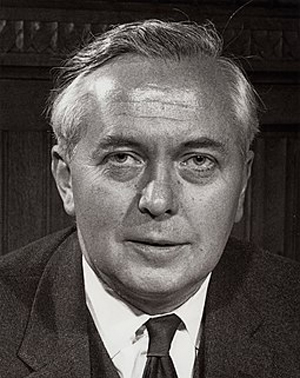

• Harold Wilson (1963–1976)

• James Callaghan (1976–1980)

• Michael Foot (1980–1983)

• Neil Kinnock (1983–1992)

• John Smith (1992–1994)

o Margaret Beckett (1994; acting)[215]

• Tony Blair (1994–2007)

• Gordon Brown (2007–2010)

o Harriet Harman (2010; acting)[215]

• Ed Miliband (2010–2015)

o Harriet Harman (2015; acting)

• Jeremy Corbyn (2015–2020)

• Keir Starmer (2020–present)

Living former Labour Party leadersAs of April 2020, there are seven living former Labour Party leaders.

• Neil Kinnock, (1983–1992), born 1942 (age 78)

• Margaret Beckett, (1994; interim), born 1943 (age 77)

• Tony Blair, (1994–2007), born 1953 (age 66)

• Gordon Brown, (2007–2010), born 1951 (age 69)

• Harriet Harman, (2010 and 2015; interim), born 1950 (age 69)

• Ed Miliband, (2010–2015), born 1969 (age 50)

• Jeremy Corbyn, (2015–2020), born 1949 (age 70)

Deputy Leaders of the Labour Party since 1922Main article: Deputy Leader of the Labour Party (UK)

• John Robert Clynes (1922–1932)

• William Graham (1931–1932)

• Clement Attlee (1932–1935)

• Arthur Greenwood (1935–1945)

• Herbert Morrison (1945–1955)

• Jim Griffiths (1955–1959)

• Aneurin Bevan (1959–1960)

• George Brown (1960–1970)

• Roy Jenkins (1970–1972)

• Edward Short (1972–1976)

• Michael Foot (1976–1980)

• Denis Healey (1980–1983)

• Roy Hattersley (1983–1992)

• Margaret Beckett (1992–1994)

• John Prescott (1994–2007)

• Harriet Harman (2007–2015)

• Tom Watson (2015–2019)

• Angela Rayner (2020–present)

Living former Labour Party deputy leadersAs of April 2020, there are five living former Labour Party deputy leaders.

• Roy Hattersley (1983–1992), born 1932 (age 87)

• Margaret Beckett (1992–1994), born 1943 (age 77)

• John Prescott (1994–2007), born 1938 (age 81)

• Harriet Harman (2007–2015), born 1950 (age 69)

• Tom Watson (2015–2019), born 1967 (age 53)

Leaders in the House of Lords since 1924• Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane (1924–1928)

• Charles Cripps, 1st Baron Parmoor (1928–1931)

• Arthur Ponsonby, 1st Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede (1931–1935)

• Harry Snell, 1st Baron Snell (1935–1940)

• Christopher Addison, 1st Viscount Addison (1940–1952)

• William Jowitt, 1st Earl Jowitt (1952–1955)

• Albert Victor Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Hillsborough (1955–1964)

• Frank Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford (1964–1968)

• Edward Shackleton, Baron Shackleton (1968–1974)

• Malcolm Shepherd, 2nd Baron Shepherd (1974–1976)

• Fred Peart, Baron Peart (1976–1982)

• Cledwyn Hughes, Baron Cledwyn of Penrhos (1982–1992)

• Ivor Richard, Baron Richard (1992–1998)

• Margaret Jay, Baroness Jay of Paddington (1998–2001)

• Gareth Williams, Baron Williams of Mostyn (2001–2003)

• Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos (2003–2007)

• Catherine Ashton, Baroness Ashton of Upholland (2007–2008)

• Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon (2008–2015)

• Angela Smith, Baroness Smith of Basildon (2015–present)

Labour Prime MinistersLabour Prime Ministers

Name / Country of birth / Periods in office

Ramsay MacDonald / Scotland / 1924; 1929–1931 (first and second MacDonald ministries)

Clement Attlee / England / 1945–1950; 1950–1951 (Attlee ministry)

Harold Wilson / England / 1964–1966; 1966–1970; 1974; 1974–1976 (first and second Wilson ministries)

James Callaghan / England 1976–1979 (Callaghan ministry)

Tony Blair / Scotland / 1997–2001; 2001–2005; 2005–2007 (Blair ministry)

Gordon Brown / Scotland / 2007–2010 (Brown ministry)

See also• Politics portal

• United Kingdom portal

• Organised labour portal

• Socialism portal

• Antisemitism in the Labour Party

• Blue Labour

• English Labour Network

• History of the Labour Party (UK)

• Labour Co-operative

• Labour In for Britain

• Labour Party in Northern Ireland

• Labour Representation Committee election results

• List of Labour Parties

• List of Labour Party (UK) MPs

• List of organisations associated with the British Labour Party

• List of UK Labour Party general election manifestos

• Politics of the United Kingdom

• Scottish Labour Party

• Socialist Labour Party (UK)

• Socialist Party (England and Wales)

• Welsh Labour

• Yorkshire and the Humber Labour Party

Notes1. The Labour Party have a policy not to stand in the 18 constituencies in Northern Ireland. The Labour Party has recently set up an officially recognised branch party in the region. The SDLP MPs unofficially take the Labour whip.

References1. Brivati & Heffernan 2000: "On 27 February 1900, the Labour Representation Committee was formed to campaign for the election of working class representatives to parliament."

2. Thorpe 2008, p. 8.

3. O'Shea, Stephen; Buckley, James (8 December 2015). "Corbyn's Labour party set for swanky HQ move". CoStar. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

4. Press Association (29 January 2020). "Labour's membership surges after election defeat, which report blames on Brexit". Evening Express. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

5. Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "United Kingdom". Parties and Elections in Europe. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

6. Adams, Ian (1998). Ideology and Politics in Britain Today (illustrated, reprint ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-7190-5056-5. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2015 – via Google Books.

7. "Local Council Political Compositions". Open Council Data UK. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

8. Matthew Worley (2009). The Foundations of the British Labour Party: Identities, Cultures and Perspectives, 1900–39. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-7546-6731-5 – via Google Books.

9. "BBC – History – The rise of the Labour Party (pictures, video, facts & news)". Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

10. Martin Crick, The History of the Social-Democratic Federation

11. p.131 The Foundations of the British Labour Party by Matthew Worley ISBN 9780754667315

12. ‘The formation of the Labour Party – Lessons for today’ Archived 22 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Jim Mortimer, 2000; Jim Mortimer was a General Secretary of the Labour Party in the 1980s

13. "Collection highlights". People's History Museum. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

14. Wright & Carter 1997.

15. Thorpe 2001.

16. "Collection Highlights, 1906 Labour Party minutes". People's History Museum. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

17. The Labour Party Archive Catalogue & Description, People's History Museum, archived from the original on 13 January 2015, retrieved 20 January 2015

18. John Foster, "Strike action and working-class politics on Clydeside 1914–1919." International Review of Social History 35#1 (1990): 33–70.

19.

http://isj.org.uk/the-russian-revolutio ... ing-class/20. Bentley B. Gilbert, Britain since 1918 (1980) p 49.

21. Rosemary Rees, Britain, 1890–1939 (2003), p. 200

22. "Red Clydeside: The Communist Party and the Labour government [booklet cover] / Communist Party of Great Britain, 1924". Glasgow Digital Library. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

23. Trevor Wilson, The downfall of the Liberal Party, 1914–1935 (1966) ch 14

24. Thorpe 2001, pp. 51–53.

25. Taylor 1965, pp. 213–214.

26. Taylor 1965, pp. 219–220, 226–227.

27. Charles Loch Mowat (1955). Britain Between the Wars, 1918–1940. Taylor & Francis. pp. 188–94. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

28. Pugh 2011, ch. 8.

29. Winkler, Henry R. (1956). "The Emergence of a Labor Foreign Policy in Great Britain, 1918-1929". The Journal of Modern History. 28 (3): 247–258. doi:10.1086/237907. JSTOR 1876236.

30. Kenneth E. Miller, Socialism and Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice in Britain to 1931 (1967) ch 4–7.

31. John Shepherd, The Second Labour Government: A reappraisal (2012).

32. Morgan, Kevin. (2006) MacDonald (20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century), Haus Publishing, ISBN 1-904950-61-2

33. Davies, A.J. (1996) To Build A New Jerusalem: The British Labour Party from Keir Hardie to Tony Blair, Abacus

34. Neil Riddell, Labour in Crisis: The Second Labour Government 1929–1931 (Manchester UP, 1999).

35. Chris Wrigley, "The Fall of the Second MacDonald Government, 1931." in T. Heppell and K. Theakston, How Labour Governments Fall (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013) pp. 38–60.

36. Thorpe, Andrew (1988). "Arthur Henderson and the British Political Crisis of 1931". The Historical Journal. 31 (1): 117–139. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012012. JSTOR 2639239.

37. Thorpe 1996.

38. Riddell 1997.

39. John Bew, Clement Attlee: The Man Who Made Modern Britain (2017).

40. "1945: Churchill loses general election". BBC News. 26 July 1945. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

41. "1945: Churchill loses general election". BBC News. 26 July 1945. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

42. Nicholas Marsh (11 May 2007). Philip Larkin: The Poems. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-137-07195-8. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

43. Wintle Justin (13 May 2013). New Makers of Modern Culture. Routledge. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-134-09454-7. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

44. Michael Jago (20 May 2014). Clement Attlee: The Inevitable Prime Minister. Biteback Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-84954-758-1. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

45. Robert Pearce (7 April 2006). Attlee's Labour Governments 1945–51. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-134-96240-2. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

46. Clark, Sir George, Illustrated History Of Great Britain, (1987) Octopus Books

47. Bew, Clement Attlee: The Man Who Made Modern Britain (2017).

48. Barlow 2008, p. 224; Beech 2006, p. 218; Clark 2012, p. 66; Heath, Jowell & Curtice 2001, p. 106; Heppell 2012, p. 38; Jones 1996, p. 8; Kenny & Smith 2013, p. 110; Leach 2015, p. 118.

49. Are the Lord's Listening?: Creating Connections Between People and Parliament First Report of Session 2008–09: Evidence. The Stationery Office. 1 June 2007. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-10-844466-1. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

50. Anthony Seldon; Kevin Hickson (2004). New Labour, old Labour: the Wilson and Callaghan governments, 1974–79. Routledge. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-415-31281-3. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

51. "Young Scots For Independence – Revealed: True oil wealth hidden to stop independence". SNP Youth. 12 September 2005. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

52. A Short History of the Labour Party by Henry Pelling

53. Vaidyanathan, Rajini (4 March 2010). "Michael Foot: What did the 'longest suicide note' say?". BBC News Magazine Online. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

54. Scott, Jennifer (18 February 2019). "Who were the Social Democratic Party?". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

55. "1983: Thatcher wins landslide victory". BBC News. 9 June 1983. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

56. Kelliher 2014.

57. Kelliher 2014, p. 256.

58. Julian Petley (2005). "Hit and Myth". In James Curran; Julian Petley; Ivor Gaber (eds.). Culture wars: the media and the British left. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 85–107. ISBN 978-0-7486-1917-7.

59. Shaw 1988, p. 267.

60. Webster, Philip (3 October 1988). "Kinnock stunned by size of his election victory". The Times (63202). p. 4. Retrieved 5 April 2015 – via The Times Digital Archive.

61. 1992: Tories win again against odds Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 5 April 2005

62. David Butler and Dennis Kavanagh, The British general election of 1997 (1997) pp 46–67.

63. Rentoul 2001, pp. 206–218.

64. Rentoul 2001, pp. 249–266.

65. "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

66. "new Labour because Britain deserves better". Labour-Party.org.uk. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008.

67. "Nigel has written a key list" (PDF). Paultruswell.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

68. "Reforms – ISSA". Issa.int. 7 January 2004. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

69. "Making a difference: Tackling poverty – a progress report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

70. "UK: numbers in low income – The Poverty Site". Poverty.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

71. "Work, Family, Health, and Well-Being: What We Know and Don't Know about Outcomes for Children" (PDF). Archived(PDF) from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

72. Mitchinson, John; Pollard, Justin; Oldfield, Molly; Murray, Andy (26 December 2009). "QI: Our Quite Interesting Quiz of the Decade, compiled by the elves from the TV show". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

73. "European Opposition To Iraq War Grows | Current Affairs". Deutsche Welle. 13 January 2003. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

74. Spencer C. Tucker (14 December 2015). U.S. Conflicts in the 21st Century: Afghanistan War, Iraq War, and the War on Terror [3 volumes]: Afghanistan War, Iraq War, and the War on Terror. ABC-CLIO. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-4408-3879-8. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

75. McClintock 2010, p. 150.

76. Bennhold, Katrin (28 August 2004). "Unlikely alliance built on opposition to Iraq war now raises questions". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

77. Fishwick, Carmen (8 July 2016). "'We were ignored': anti-war protesters remember the Iraq war marches". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

78. staff, Guardian (6 July 2016). "Chilcot report: key points from the Iraq inquiry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

79. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

80. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

81. I will quit within a year – Blair Archived 17 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 7 September 2007

82. Lovell, Jeremy (30 May 2008). "Brown hit by worst party rating". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

83. Kirkup, James; Prince, Rosa (30 July 2008). "Labour Party membership falls to lowest level since it was founded in 1900". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

84. John Marshall: Membership of UK political parties; House of Commons, SN/SG/5125; 2009, page 9 Archived 21 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

85. "New figures published showing political parties' donations and borrowing". The Electoral Commission. 22 May 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

86. Dathan, Matt (26 November 2015). "Labour pays off £25m debt and abandons move out of Westminster". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

87. UK election results: data for every candidate in every seat Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian (London), 7 May 2010

88. Wintour, Patrick (7 May 2010). "General election 2010: Can Gordon Brown put together a rainbow coalition?". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

89. Mason, Trevor; Smith, Jon (10 May 2010). "Gordon Brown to resign as Labour leader". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

90. "Harman made acting Labour leader". BBC News. 11 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

91. Miliband, Ed (25 May 2012). "Building a responsible capitalism". Juncture (IPPR). Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

92. "Ed Miliband: Surcharge culture is fleecing customers". BBC News. 19 January 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

93. "Ed Miliband speech on Social Mobility to the Sutton Trust". The Labour Party. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

94. "Ed Miliband's Banking Reform Speech: The Full Details". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

95. Neild, Barry (6 July 2011). "Labour MPs vote to abolish shadow cabinet elections". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

96. "John Prescott calls for Labour shadow cabinet reshuffle". BBC News. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

97. "At-a-glance: Elections 2012". BBC News. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 31 May2013.

98. "Vote 2012: Welsh Labour's best council results since 1996". BBC News. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

99. "Labour wins overall majority on Glasgow City Council". BBC News. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

100. Andrew Grice (28 February 2014). "Tony Blair backs Ed Miliband's internal Labour reforms". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

101. Andrew Sparrow (1 March 2014). "Miliband wins vote on Labour party reforms with overwhelming majority". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

102. Ray Collins (February 2014). The Collins Review Into Labour Party Reform (PDF) (Report). Labour Party. Archived(PDF) from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

103. "European voters now calling for less EU". The UK News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May2014.

104. "Vote 2014 – Election Results for Councils in England". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

105. "Is Osborne right that a smaller state means a richer UK?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

106. "How many seats did Labour win?". The Independent. London. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

107. "Scotland election 2015 results: SNP landslide amid almost total Labour wipeout – as it happened". The Daily Telegraph. London. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

108. "UK Election: Telling the story using numbers". Irish Times. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

109. "Election 2015 results MAPPED: 2015 full list". The Daily Telegraph. London. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

110. "Labour election results: Ed Miliband resigns as leader". BBC News. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

111. Mason, Rowena (12 September 2015). "Labour leadership: Jeremy Corbyn elected with huge mandate". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

112. Eaton, George (12 September 2015). "The epic challenges facing Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

113. "Labour leadership: Huge increase in party's electorate". BBC. 12 August 2015. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

114. "Jeremy Corbyn: Membership of Labour party has doubled since 2015 general election". International Business Times. 8 October 2015. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

115. Rajeev Syal; Frances Perraudin; Nicola Slawson (27 June 2016). "Shadow cabinet resignations: who has gone and who is staying". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

116. Asthana, Anushka; Elgot, Jessica; Syal, Rajeev (28 June 2016). "Jeremy Corbyn suffers heavy loss in Labour MPs confidence vote". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

117. "Labour leadership: Angela Eagle says she can unite the party". BBC News. 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

118. Grice, Andrew (19 July 2016). "Labour leadership election: Angela Eagle pulls out of contest to allow Owen Smith straight run at Jeremy Corbyn". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

119. "Labour leadership: Jeremy Corbyn defeats Owen Smith". BBC News. 24 September 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

120. "Jeremy Corbyn Is Re-elected as Leader of Britain's Labour Party". The New York Times. 24 September 2016. Archivedfrom the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

121. Mason, Rowena; Stewart, Heather (1 February 2017). "Brexit bill: two more shadow cabinet members resign". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

122. Chorley, Matt (2 February 2017). "Brexit is an instrument of torture for Labour". The Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

123. Savage, Michael (3 February 2017). "Labour members resign in their thousands over vote". The Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

124. Bush, Stephen (1 February 2017). "Labour's next leadership election will be about Europe, but don't bet on Clive Lewis just yet". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

125. "Theresa May seeks general election". BBC News. 18 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

126. Castle, Stephen (23 September 2018). "Jeremy Corbyn, at Labour Party Conference, Faces Pressure on New Brexit Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019.

127. Travis, Alan (11 June 2017). "Labour can win majority if it pushes for new general election within two years". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

128. Griffin, Andrew (9 June 2017). "Corbyn gives Labour biggest vote share increase since 1945". The London Economic. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

129. Bulman, May (13 June 2017). "Labour Party membership soars by 35,000 since general election". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

130. Travis, Alan, and Phillip Inman (1 June 2017). "Labour manifesto 2017: the key points, pledges and analysis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019.

131. Stewart, Heather (22 September 2017). "The inside story of Labour's election shock". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019.

132. Smith, Matthew (11 July 2017). "Why people voted Labour or Conservative at the 2017 general election". YouGov. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019.

133. Wintour, Patrick, and Rowena Mason (27 December 2017). "Labour voters could abandon party over Brexit stance, poll finds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019.

134. "Labour's full 'conference policy' on Brexit/referendum - a summary in 3 lines". The Skwawkbox. 30 April 2019. Archivedfrom the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

135. "Jeremy Corbyn: we'll back a second referendum to stop Tory no-deal Brexit". The Guardian. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

136. Sparrow, Andrew, and Kevin Rawlinson (25 February 2019). "Brexit: Labour will back amendment for second referendum, says Corbyn – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019.

137. "Jeremy Corbyn regrets comments about 'anti-Semitic' mural". BBC News. 23 March 2018. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019.

138. Coulter, Martin (25 August 2019). "Jeremy Corbyn defends 'Zionists and English irony' comments". PoliticsHome. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019.

139. Stewart, Heather, and Sarah Marsh (1 May 2019). "Jewish leaders demand explanation over Corbyn book foreword". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019.

140. "Jeremy Corbyn apologises over 2010 Holocaust event". BBC News. 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019.

141. Lee, Georgina (29 November 2019). "FactCheck: Leaked document casts doubt on Corbyn antisemitism claim". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019.

142. "Labour must move faster on antisemitism, says McDonnell, as Austin quits - politics live". The Guardian. 22 February 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019.

143. "Labour party must listen to the Jewish community on defining antisemitism". The Guardian. 16 July 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019.

144. "Luciana Berger quits the Labour party over 'institutional anti-semitism'". ITV. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019.

145. "Louise Ellman quits Labour party with fierce attack on Corbyn". The Guardian. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019.

146. Sugarman, Daniel (13 September 2018). "More than 85 per cent of British Jews think Jeremy Corbyn is antisemitic". Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019.

147. "Labour: 673 anti-Semitism complaints in 10 months". BBC News. 11 February 2019. Archived from the original on 25 November 2019.

148. Sienna Rodgers (11 February 2019). "Jennie Formby provides numbers on Labour antisemitism cases". LabourList. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

149. Mirvis, Ephraim (25 November 2019). "What will become of Jews in Britain if Labour forms the next government?". The Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

150. Zeffman, Henry (26 November 2019). "Labour antisemitism: Corbyn not fit for high office, says Chief Rabbi Mirvis". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019.

151. Mason, Rowena (28 May 2019). "Equality body launches investigation of Labour antisemitism claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019.

152. "Labour Party manifesto 2019: 12 key policies explained". BBC News. 21 November 2019. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

153. Mason, Paul (15 August 2016). "The parallels between Jeremy Corbyn and Michael Foot are almost all false". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

154. "Jeremy Corbyn: 'I did everything I could to lead Labour'". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

155. "Labour leadership race threatens party civil war as MPs fear 'continuity Corbyn' figure". The Independent. 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

156. "General election 2019: Blair attacks Corbyn's 'comic indecision' on Brexit". BBC News. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

157. "Blair: 2019 general election result 'brought shame on us'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

158. "New Labour leader Keir Starmer vows to lead party into 'new era'". BBC News. 4 April 2020.

159. Bakker, Ryan; Jolly, Seth; Polk, Jonathan. "Mapping Europe's party systems: which parties are the most right-wing and left-wing in Europe?". London School of Economics / EUROPP – European Politics and Policy. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

160. Giddens, Anthony (17 May 2010). "The rise and fall of New Labour". The New Statesman. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

161. Peacock, Mike (8 May 2015). "The European centre-left's quandary". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015. A crushing election defeat for Britain's Labour party has laid bare the dilemma facing Europe's centre-left.

162. Dahlgreen, Will (23 July 2014). "Britain's changing political spectrum". YouGov. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

163. Budge 2008, pp. 26–27.[verification needed]

164. [159][160][161][162][163]

165. Martin Daunton "The Labour Party and Clause Four 1918–1995" Archived 21 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, History Review 1995 (History Today website)

166. Philip Gould The Unfinished Revolution: How New Labour Changed British Politics Forever, London: Hachette digital edition, 2011, p.30 (originally published by Little, Brown, 1998)

167. John Rentoul "'Defining moment' as Blair wins backing for Clause IV" Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 14 March 1995

168. "Labour Party Rule Book" (PDF). LabourList. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

169. "How we work – How the party works". Labour.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

170. Lund 2006, p. 111.

171. Mulholland, Helene (7 April 2011). "Labour will continue to be pro-business, says Ed Miliband". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

172. Hay 2002, pp. 114–115; Hopkin & Wincott 2006; Jessop 2004; McAnulla 2006, pp. 118, 127, 133, 141; Merkel et al. 2008, pp. 4, 25–26, 40, 66.

173. Lavelle, Ashley (2008). The Death of Social Democracy, Political Consequences for the 21st Century. Ashgate.

174. Daniels & McIlroy 2009; McIlroy 2011; Smith 2009; Smith & Morton 2006.

175. Crines 2011, p. 161.

176. "What's left of the Labour left?". Total Politics. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

177. Akehurst, Luke (14 March 2011). "Compass and Progress: A tale of two groupings". LabourList. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

178. Angell, Richard (2 March 2017). "The problem is politics, not PR". Progress Online. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2017. few come more 'militant anti-Corbyn' than I

179. "What would Jeremy do?". Progress Online. 20 July 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 24 July2017.

180. Momentum: Corbyn-backing organisation now has 40,000 paying members, overtaking Green Party Archived 5 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Independent. Author – Ashley Cowburn. Published 4 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

181. "Labour Party Annual Conference Report", 1931, p. 233.

182. "The long and the short about Labour's red rose". The Daily Telegraph. London. 26 June 2001. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

183. Grady, Helen (21 March 2011). "Blue Labour: Party's radical answer to the Big Society?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

184. Hoggart, Simon (28 September 2007). "Red Flag rises above a dodgy future". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

185. "Video: Ed Miliband sings The Red Flag and Jerusalem at the Labour Party Conference". The Daily Telegraph. London. 29 September 2011. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

186. "Anger over 'union debate limit'". BBC News. 19 September 2007. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

187. Athelstane Aamodt (17 September 2015). "Unincorporated associations and elections". Local Government Lawyer. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

188. "Watt (formerly Carter) (sued on his own on behalf of the other members of the Labour Party) (Respondent) v. Ahsan (Appellant)". The Lords of Appeal. House of Lords. 16–18 July 2007. [2007] UKHL 51. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

189. Oliver Wright (10 September 2015). "Labour leadership contest: After 88 days of campaigning, how did Labour's candidates do?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 September 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015. the electorate is divided into three groups: 292,000 members, 148,000 union "affiliates" and 112,000 registered supporters who each paid £3 to take part

190. Dan Bloom (25 August 2015). "All four Labour leadership candidates rule out legal fight – despite voter count plummeting by 60,000". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015. total of those who can vote now stands at 550,816 ... The total still eligible to vote are now 292,505 full paid-up members, 147,134 supporters affiliated through the unions and 110,827 who've paid a £3 fee.

191. Waugh, Paul (13 June 2017). "Labour Party Membership Soars By 35,000 In Just Four Days – After 'Corbyn Surge' In 2017 General Election". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

192. "Political party membership figures published by House of Commons library". 3 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

193. Sabbagh, Dan (22 August 2018). "Labour is Britain's richest party – and it's not down to the unions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

194. "Labour Party membership HAS dropped reveals leaked data - but not by what some people claim". 7 February 2019. Archived from the original on |archive-url= requires |archive-date= (help).

195. "Labour membership falls 10% amid unrest over Brexit stance". Archived from the original on 16 February 2019.

196. "More than half of Labour members still want Jeremy Corbyn to lead party into next election". Archived from the originalon 23 July 2019.

197. Labour Party membership form at the Wayback Machine (archive index), ca. 1999. Retrieved 31 March 2007. "Residents of Northern Ireland are not eligible for membership."

198. Understanding Ulster Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Antony Alcock, Ulster Society Publications, 1997. Chapter II: The Unloved, Unwanted Garrison. Via Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

199. "Labour NI ban overturned". BBC News. 1 October 2003. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 31 May2013.

200. "LPNI prepare to fight elections". Labour Party in Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016.

201. "Trade Union and Labour Party Liaison Organisation (TULO)". Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

202. RMT 'breached' Labour party rules Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 27 January 2004

203. Labour's link to unions in danger Archived 8 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 16 June 2004

204. "CWU resolution to TUC Congress 2009". TUC Congress Voices. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

205. Dunton, Jim (17 June 2009). "Unison: "no more blank cheques' for Labour". Local Government Chronicle. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

206. "Miliband urges 'historic' changes to Labour's union links". BBC News. 9 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

207. Features (24 December 2015). "Corbyn has brought back Labour, so the FBU brought back the firefighters". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

208. "Party of European Socialists". Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

209. Kowalski, Werner. Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923–1940 Archived 2 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Berlin: Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften, 1985

210. Black, Ann (6 February 2013). "Report from Labour's January executive". Leftfutures.org. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

211. "Progressive Alliance: Sozialdemokraten gründen weltweites Netzwerk – SPIEGEL ONLINE". Spiegel.de. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

212. "Vorwurf: SPD "spaltet die Linken"". Kurier.At. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

213. "Vorwärts in eine ungewisse Zukunft – 150 Jahre SPD – Politik – Nachrichten – morgenweb". Morgenweb.de. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

214. "Sozialdemokratische Parteien gründen neues Bündnis | Aktuell Welt | DW.DE | 22 May 2013". Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

215. "Labour Party Rule Book 2014" (PDF). House of Commons Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016. When the party is in opposition and the party leader, for whatever reason, becomes permanently unavailable, the deputy leader shall automatically become party leader on a pro-tem basis.

Bibliography• Barlow, Keith (2008). The Labour Movement in Britain from Thatcher to Blair. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-55137-0.

• Beech, Matt (2006). The Political Philosophy of New Labour. International Library of Political Studies. 6. London: Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1-84511-041-3.

• Bell, Geoffrey (1982). Troublesome Business: Labour Party and the Irish Question. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-86104-373-6.

• Brivati, Brian; Heffernan, Richard (2000). The Labour Party: A Centenary History. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23458-4.

• Budge, Ian (2008). "Great Britain and Ireland: Variations in Party Government". In Colomer, Josep M. (ed.). Comparative European Politics (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-07354-2.

• Clark, Alistair (2012). Political Parties in the UK. Contemporary Political Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-36868-2.

• Crines, Andrew Scott (2011). Michael Foot and the Labour leadership. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-4438-3239-7.

• Heath, Anthony F.; Jowell, Roger M.; Curtice, John K. (2001). The Rise of New Labour: Party Policies and Voter Choices: Party Policies and Voter Choices. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-152964-1.

• Daniels, Gary; McIlroy, John, eds. (2009). Trade Unions in a Neoliberal World: British Trade Unions under New Labour. Routledge Research in Employment Relations. 20. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42663-3.

• Kenny, Michael; Smith, Martin J. (2013) [1997]. "Discourses of Modernization: Gaitskell, Blair and Reform of Clause IV". In Denver, David; Fisher, Justin; Ludlam, Steve; Pattie, Charles (eds.). British Elections and Parties Review. 7. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25578-7.

• Hay, Colin (2002). British Politics Today. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-2319-1.

• Heppell, Timothy (2012). "Hugh Gaitskell, 1955–63". In Heppell, Timothy (ed.). Leaders of the Opposition: From Churchill to Cameron. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-29647-3.

• Hopkin, Jonathan; Wincott, Daniel (2006). "New Labour, Economic Reform and the European Social Model". British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 8 (1): 50–68. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.554.5779. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2006.00227.x. ISSN 1467-856X.

• Jessop, Bob (2004) [2003]. "From Thatcherism to New Labour: Neo-liberalism, Workfarism and Labour-market Regulation". In Overbeek, Henk (ed.). The Political Economy of European Employment: European Integration and the Transnationalization of the (Un)employment Question. RIPE Series in Global Political Economy. London: Routledge. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.4922. ISBN 978-0-203-01064-8.

• Jones, Tudor (1996). Remaking the Labour Party: From Gaitskell to Blair. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-80132-9.

• Kelliher, Diarmaid (2014). "Solidarity and Sexuality: Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners 1984–5" (PDF). History Workshop Journal. 77 (1): 240–262. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbt012. ISSN 1477-4569.

• Leach, Robert (2015). Political Ideology in Britain (3rd ed.). London: Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-137-33255-4.

• Lund, Brian (2006). "Distributive Justice and Social Policy". In Lavalette, Michael; Pratt, Alan (eds.). Social Policy: Theories, Concepts and Issues (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications. pp. 107–123. ISBN 978-1-4129-0170-3.

• McAnulla, Stuart (2006). British Politics: A Critical Introduction. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6156-8.

• McClintock, John (2010). The Uniting of Nations: An Essay on Global Governance (3rd ed.). Brussels: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-90-5201-588-0.

• McIlroy, John (2011). "Britain: How Neo-Liberalism Cut Unions Down to Size". In Gall, Gregor; Wilkinson, Adrian; Hurd, Richard(eds.). The International Handbook of Labour Unions: Responses to Neo-Liberalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 82–104. ISBN 978-1-84844-862-9.

• Merkel, Wolfgang; Petring, Alexander; Henkes, Christian; Egle, Christoph (2008). Social Democracy in Power: The Capacity to Reform. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-43820-9.

• Pugh, Martin (2011) [2010]. Speak for Britain! A New History of the Labour Party. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-952078-8.

• Rentoul, John (2001). Tony Blair: Prime Minister. London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-85496-2.

• Riddell, Neil (1997). "The Catholic Church and the Labour Party, 1918–1931". Twentieth Century British History. 8 (2): 165–193. doi:10.1093/tcbh/8.2.165. ISSN 1477-4674.

• Shaw, Eric (1988). Discipline and Discord in the Labour Party: The Politics of Managerial Control in the Labour Party, 1951–87. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2483-2.

• Smith, Paul (2009). "New Labour and the Commonsense of Neoliberalism: Trade Unionism, Collective Bargaining and Workers' Rights". Industrial Relations Journal. 40 (4): 337–355. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2338.2009.00531.x. ISSN 1472-9296.

• Smith, Paul; Morton, Gary (2006). "Nine Years of New Labour: Neoliberalism and Workers' Rights" (PDF). British Journal of Industrial Relations. 44 (3): 401–420. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2006.00506.x. ISSN 1467-8543. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

• Taylor, A. J. P. (1965). English History: 1914–1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

• Thorpe, Andrew (1996). "The Industrial Meaning of 'Gradualism': The Labour Party and Industry, 1918–1931". Journal of British Studies. 35 (1): 84–113. doi:10.1086/386097. hdl:10036/19512. ISSN 1545-6986. JSTOR 175746.

• ——— (2001). A History of the British Labour Party (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-333-92908-7.

• ——— (2008). A History of the British Labour Party (3rd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-11485-3.

• Wright, Tony; Carter, Matt (1997). The People's Party: The History of the Labour Party. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27956-4.

Further reading• Bew, John. Clement Attlee: The Man Who Made Modern Britain (2017). the fullest biography.

• Cole, G. D. H. A History of the Labour Party from 1914 (1969).

• Davies, A. J. To Build a New Jerusalem: Labour Movement from the 1890s to the 1990s (1996).

• Driver, Stephen and Luke Martell. New Labour: Politics after Thatcherism (Polity Press, wnd ed. 2006).

• Field, Geoffrey G. Blood, Sweat, and Toil: Remaking the British Working Class, 1939–1945 (2011) doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199604111.001.0001 online

• Foote, Geoffrey. The Labour Party's Political Thought: A History (Macmillan, 1997).

• Francis, Martin. Ideas and Policies under Labour 1945–51 (Manchester UP, 1997).

• Howell, David.British Social Democracy (Croom Helm, 1976)

• Howell, David. MacDonald's Party, (Oxford University Press, 2002).

• Kavanagh, Dennis. The Politics of the Labour Party (Routledge, 2013).

• Matthew, H. C. G., R. I. McKibbin, J. A. Kay. "The Franchise Factor in the Rise of the Labour Party," English Historical review91#361 (Oct. 1976), pp. 723–752 in JSTOR

• Miliband, Ralph. Parliamentary Socialism (1972).

• Mioni, Michele. "The Attlee government and welfare state reforms in post-war Italian Socialism (1945–51): Between universalism and class policies." Labor History 57#2 (2016): 277–297. doi:10.1080/0023656X.2015.1116811

• Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour in Power, 1945–51, OUP, 1984

• Morgan, Kenneth O. Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants, Hardie to Kinnock OUP, 1992, scholarly biographies of 30 key leaders.

• Pelling, Henry, and Alastair J. Reid, A Short History of the Labour Party, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005 ed.

• Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left in the 1930s, Cambridge University Press, 1977.

• Plant, Raymond, Matt Beech and Kevin Hickson (2004), The Struggle for Labour's Soul: understanding Labour's political thought since 1945, Routledge

• Clive Ponting, Breach of Promise, 1964–70 (Penguin, 1990).

• Reeves, Rachel, and Martin McIvor. "Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state." Renewal: a Journal of Labour Politics 22.3/4 (2014): 42+ online.

• Rogers, Chris. "‘Hang on a Minute, I've Got a Great Idea’: From the Third Way to Mutual Advantage in the Political Economy of the British Labour Party." British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15#1 (2013): 53–69.

• Rosen, Greg, ed. Dictionary of Labour Biography. Politicos Publishing, 2001, 665pp; short biographies.

• Rose, Richard. The relation of socialist principles to British Labour foreign policy, 1945–51 (PhD. Dissertation. U of Oxford, 1960)online

• Rosen, Greg. Old Labour to New, Politicos Publishing, 2005

• Shaw, Eric. The Labour Party since 1979: Crisis and Transformation (Routledge, 1994).

• Shaw, Eric. "Understanding Labour Party Management under Tony Blair." Political Studies Review 14.2 (2016): 153–162.

• Taylor, Robert. The Parliamentary Labour Party: A History 1906–2006 (2007)

• Worley, Matthew. Labour Inside the Gate: A History of the British Labour Party between the Wars (2009)

External links

Official party websites• Labour

• Scottish Labour

• Welsh Labour

• Young Labour

Other• Labour History Group website

• Guardian Unlimited Politics—Special Report: Labour Party

• Tony Benn Speech Archive, former Labour Party Chairman, 1971–72

• Labour History Archive and Study Centre holds archives of the National Labour Party

• "Déroute historique des travaillistes". L'Humanité. 5 May 2008.

• Labour Campaign for Electoral Reform website

• Labour Party (UK) discography at Discogs

• Catalogue of the Labour Party East Midlands Region archives held at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick