Our story: 150 years of the National Secular Society: The NSS has been on the forefront of campaigning for a fairer, secular society for over 150 years. We have gone from being prosecuted for blasphemy to being instrumental in its abolition.

by National Secular Society

Accessed: 4/11/20

Our story began in 1866 when a large number of secularist groups from around the UK came together to strengthen their campaigns. Their leader was Charles Bradlaugh. Since those early days the National Secular Society has pioneered many important social reforms and society has changed a lot.

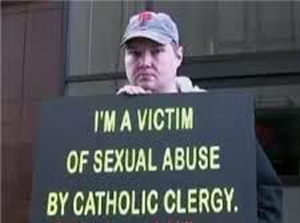

For centuries, religion-based laws forbade entry for non-believers into parliament. They banned abortion, divorce, contraception, homosexuality, blasphemy and even cremation. Those laws have now been dismantled; human rights and equality for minorities are broadly accepted and protected by law.

In the struggles to bring about these reforms, the NSS has always played a prominent role and sometimes a decisive one.

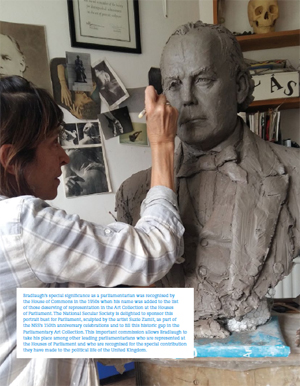

To mark our 150th anniversary in 2016 the National Secular Society commissioned a portrait bust of Charles Bradlaugh which is now on display in the Palace of Westminster as part of the Parliamentary Art Collection. We also produced an anniversary brochure giving a potted history of our first 150 years.

Read on to find out more about our story, and some of the significant historical events and people that illustrate the NSS's rich history.

Explore our story

Our archives

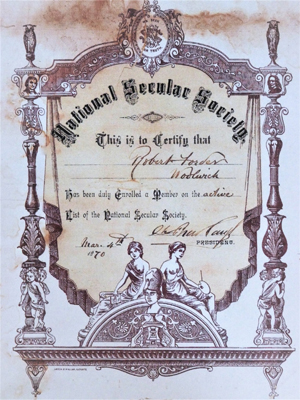

Following a collaborative archival project between Bishopsgate Institute and the Conway Hall Ethical Society, the National Secular Society's historical archives are now available to the public at Conway Hall.

The National Secular Society: The First 150 Years 1866 – 2016

Introduction

Like any organisation that has campaigned to make radical changes to the constitutional structure of our country, the National Secular Society has encountered much resistance, and this has been true throughout its 150 year history.

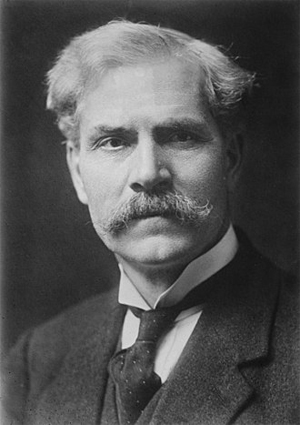

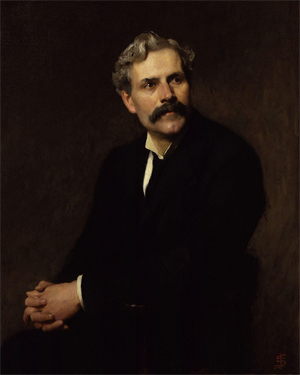

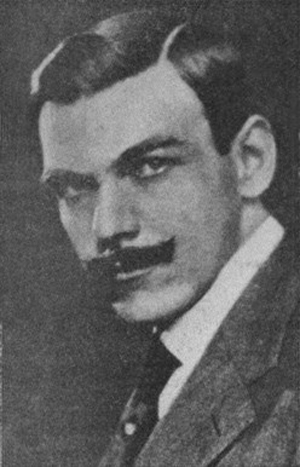

Founded in 1866 by Charles Bradlaugh, a brilliant orator and self-taught lawyer and later to become a radical politician, the ambitions of the NSS have met with successes and defeats in almost equal measure. On the credit side, religion-based laws that for centuries forbade entry for non-believers into Parliament and had banned abortion, divorce, contraception, homosexuality, blasphemy — and even cremation — have been dismantled. Human rights and equality for minorities are now accepted and protected by law. In the struggles to bring about these reforms, the NSS has always played a prominent role and sometimes a decisive one.

On the debit side, the Anglican and Catholic Churches still have a disproportionate hold on our education system, and despite its diminishing size and reduced influence among the population, the Church of England remains established by law, a status that brings with it many unjustified privileges – including representation as of right in Parliament.

Bradlaugh, as you will see from the following pages, was denied a seat in Parliament — despite being repeatedly reelected — simply because he was an atheist. At that time, the swearing of a religious oath by parliamentarians was mandatory. Through dogged determination, Bradlaugh overcame religious objections and his Oaths Act made it possible for MPs to have a choice to affirm rather than take an oath.

Bradlaugh’s attacks on religion, particularly on the outrageous privileges of the Established Church, were brilliant, scorching and necessary. More recently, though, as the Church of England and its influence has dramatically withered away, the NSS has changed its focus to one that is neutral on religion.

Today the Society’s focus is on the struggle to build a more equal, inclusive and just society based on secularism and on the application of universal human rights.Basing our activities on our Secular Charter, we continue to oppose religious privilege and to propose a society that is far more suited to the diverse nation that Britain has become in the 21st century.

Of course, secularism alone cannot stop religious conflicts, but it can prevent the power of the state being used by any particular religion to persecute others.

Secularism only works when it is an adjunct of democracy, when it is willingly accepted by the majority. It is the job of the National Secular Society now to persuade Britain that secularism is a friend and not an enemy. We must put a convincing case that the time has come to formulate a new secular constitution that is fair to all, and gives privilege to none.

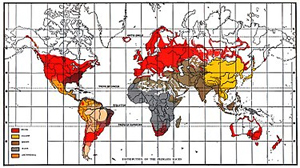

In other parts of the world where secularism has been established constitutionally – such as in Turkey – we have seen how fragile it can be when faced by determined theocrats. In many other parts of the world we can see how religion can be recruited so easily to support the political ambitions of tyrants and demagogues. Throughout the Middle East and to a degree in Russia, religion has become a tool of manipulation and division. Even in the USA, where the establishment of religion is forbidden by the constitution, theocrats are finding ingenious ways of undermining and damaging the first amendment. In France, where state and church were strictly separated in 1905, the rise of Islam has posed grave threats to the traditional concept of laïcité.

I am proud to be the twelfth President of the National Secular Society and I value being part of its long tradition and history. It continues to evolve to meet the changes in society. We all still have much to do. The need for secularism has never been more pressing. The fight must continue.

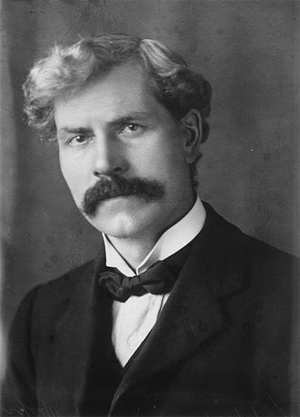

Terry Sanderson

President

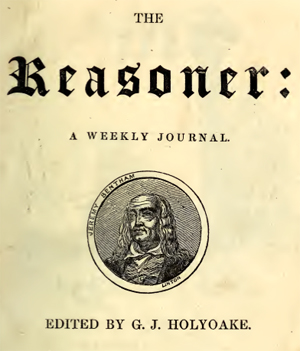

'Secularism' to Mean a Positive Alternative to Atheism: 1851 Secularism Defined

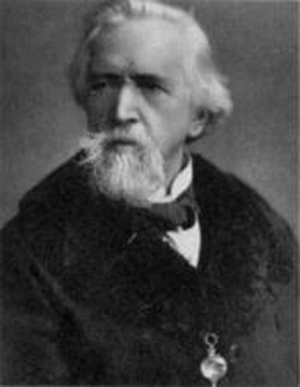

by George Jacob Holyoake (1817–1906)

1851

Secularism Defined

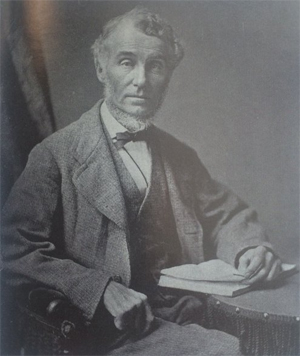

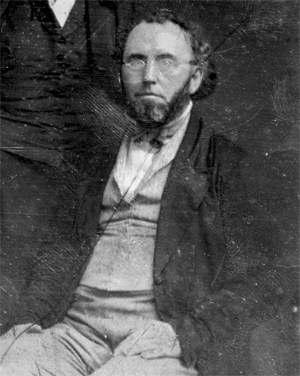

George Jacob Holyoake

(1817–1906)

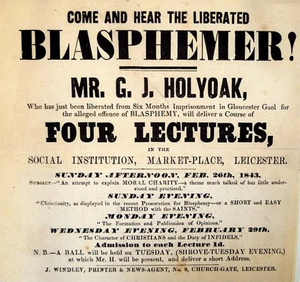

George Jacob Holyoake, a British secularist and newspaper editor who was prosecuted for blasphemy in 1842, adopted the word ‘secularism’ to mean a positive alternative to atheism – ‘the province of the real’. Secularist groups formed under the influence of Owenite socialist groups.

1863

Civil Marriages Introduced

The Church of England’s stranglehold on marriage was broken by the Marriage Act which created the possibility of civil marriages for Roman Catholics, Hindus, Muslims, non-conformists and atheists. It was fiercely resisted by the Church of England, with the Bishop of Exeter calling it “a disgrace to British legislation”. Until that time, the only legally recognised marriages were those conducted on Church of England premises by Anglican clergy. Eventually registry offices were established to facilitate civil marriages with no religious character.

The Church of England’s stranglehold on marriage… and atheists

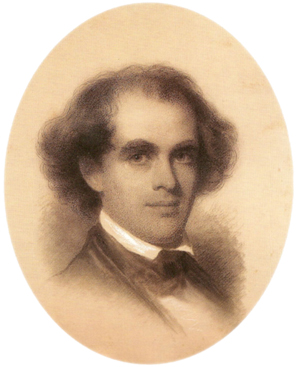

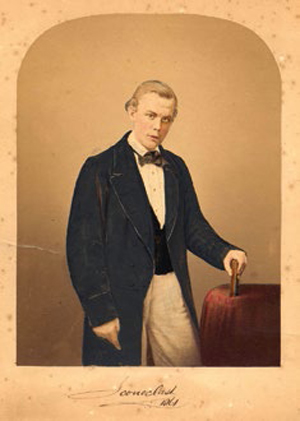

The young Charles Bradlaugh adopted the pseudonym ‘Iconoclast’ to protect his employer’s reputation (1861)

1866

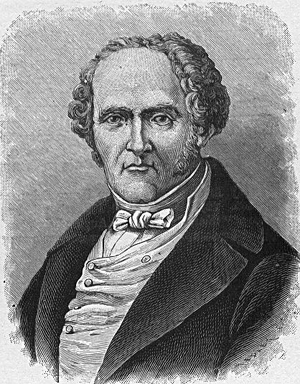

NSS Founded by

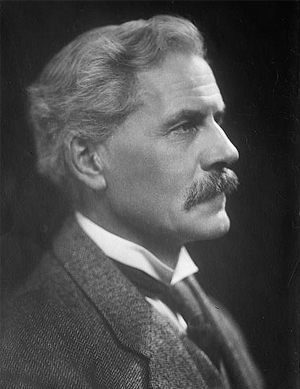

Charles Bradlaugh

(1833–1891)

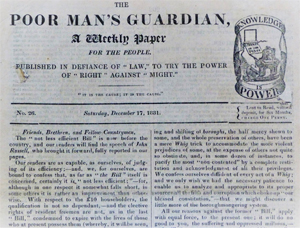

As an avowed atheist, republican, promoter of the right of women to vote and advocate of birth control, Charles Bradlaugh became one of Victorian England’s most detested and, at the same time, admired men. He was a great orator and filled venues of many thousands throughout the UK (which then included all of Ireland). He founded the NSS in 1866. In the same year, the periodical The National Reformer was started in Sheffield and became a kind of diary of the organisation. The founding principles of the NSS were: “to promote human happiness, to fight religion as an obstruction, to attack the legal barriers to Freethought” and its objects were “Freethought propaganda, parliamentary action to remove disabilities, secular schools and instruction classes, mutual help and a fund for the distressed. “

The NSS was formed as a national society, a federation of the numerous local secular societies throughout Britain.

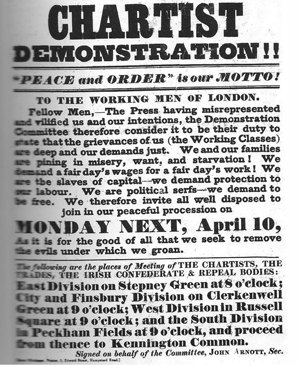

1871

Bradlaugh The Republican

A Trafalgar Square meeting to protest against grants to the royal family was banned. Bradlaugh defiantly reconvened it and warned the Home Secretary that his threat of force would be resisted. The Government backed down and rescinded the ban half an hour before the start of the demonstration. Bradlaugh stepped down temporarily from the Presidency of the NSS.

1872

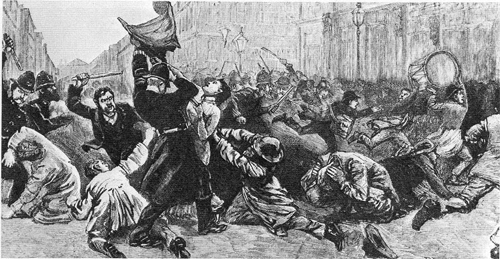

Bradlaugh Resists the Ban on Public Meetings of Secularists

After some attendees at a secularist rally in Hyde Park had been convicted in court, Bradlaugh together with the Reform League called a mass protest meeting. Although the military was on standby to confront the demonstrators, they were allowed to pass without interference, thereby establishing the right to peaceful assembly. The regulations banning such gatherings were annulled, and the Home Secretary Walpole resigned. Bradlaugh resumed his presidency of the NSS, after calling for the Royal Family to be impeached.

No 5 Bacchus Walk, Hoxton – Bradlaugh’s birthplace in 1833

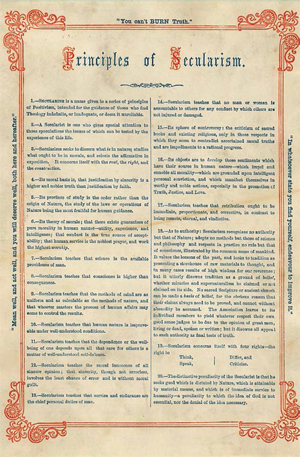

Principles of Secularism, an early version of the Secular Charter

Principles of Secularism.

1. Secularism is a name given to a series of principles of Positivism, intended for the guidance of those who find Theology indefinite, or inadequate, or deem it unreliable.

2. A Secularist is one who gives special attention to those speculations the impact of which can be tested by the experience of this life.

3. Secularism seeks to discern what is in nature; studies what ought to be in morals, and selects the affirmative in exposition. It concerns itself with the real, the right, and the constructive.

4. Its moral basis is, that justification by sincerity is a higher and nobler truth than justification by faith.

5. Its province of study is the order rather than the origin of Nature, the study of the laws or oeprations of Nature being the most fruitful for human guidance.

6. Its theory of morals; that there exists guarantees of pure morality in human nature -- utility, experience, and intelligence; that conduct is the true source of acceptability; that human service is the noblest prayer, and work the highest worship.

7. Secularism teaches that science is the available providence of man.

8. Secularism teaches that conscience is higher than consequences.

9. Secularism teaches that the methods of mind are as uniform and as calculable as the methods of nature, and that whoever masters the process of human affairs may come to control the results.

10. Secularism teaches that human nature is improveable under well-understood conditions.

11. Secularism teaches that the dependence or the well-being of one depends upon all, that care for others is a matter of well-understood self-defence.

12. Secularism teaches the moral innocence of all sincere opinion, that sincerity, though not errorless, involves the least chance of error and is without moral guilt.

13. Secularism teaches that service and endurance are the chief personal duties of man.

14. Secularism teaches that no man or woman is accountable to others for any conduct by which others are not injured or damaged.

15. Its sphere of controversy: the criticism of sacred books and existing religions, only in those respects in which they seem to contradict ascertained moral truths and are impediments to a rational progress.

16. Its objects are to develop those sentiments which have their sources in human nature -- which impel and ennoble all morality -- which are grounded upon intelligent personal conviction, and which manifest themselves in worthy and noble actions, especially in the promotion of Truth, Justice, and Love.

17. Secularism teaches that retribution ought to be immediate, proportionate, and corrective, in contrast to being remote, eternal, and vindictive.

18. As to authority: Secularism recognizes no authority but that of Nature; adopts no methods but those of science and philosophy and respects in practice no rule but that of conscience, illustrated by the common sense of mankind. It values the lessons of the past, and looks to tradition as presenting a storehouse of raw materials to thought, and in many cases results of high wisdom for our reverence; but it utterly disowns traditions as a ground of belief, whether miracles and supernaturalism be claimed or not claimed on its side. So sacred Scripture or ancient church can be made a basis of belief, for the obvious reason that their claims always need to be proved, and cannot without absurdity be assumed. The Association leaves to its individual members to yield whatever respect their own good sense judges to be due to the opinion of great men, living or dead, spoken or written; but it disowns all appeal to such authority as final tests of truth.

19. Secularism concerns itself with four rights -- the right to Think, Speak, Differ, and Criticize.

20. The distinctive peculiarity of the Secularist is that he seeks good which is dictated by Nature, which is attainable by material means, and which is of immediate service to humanity -- a peculiarity to which the idea of God is not essential, nor the denial of the idea necessary.

"Mean well, and act well, and you will deserve well, both here and hereafter."

"You can't BURN Truth."

"In whatsoever state you find yourself, endeavour to improve it."

1874

Annie Besant Joins the NSS

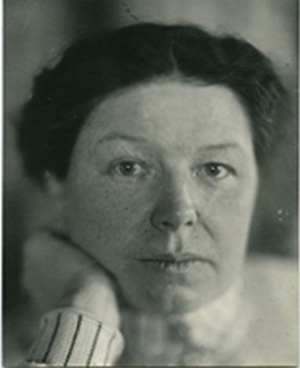

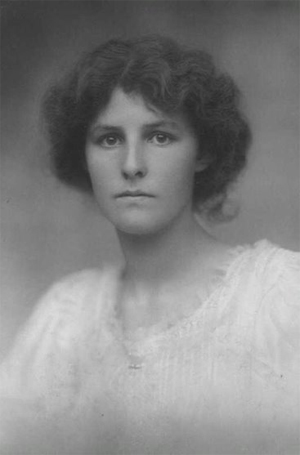

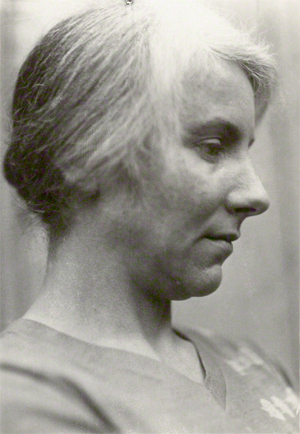

Annie Besant, the divorced wife of a clergyman, joined the NSS and was soon a formidable ally to Bradlaugh. She excelled as a lecturer, public speaker and agitator. She rapidly became a vicepresident of the NSS. She wrote widely in opposition to religion and in support of euthanasia. She was abused and stones were thrown at her at a meeting promoting Darwinism.

1877

The First Prosecution of Knowlton’s Birth Control Pamphlet

Charles Watts was arrested for publishing The Fruits of Philosophy, a pamphlet by an American doctor, Charles Knowlton, explaining birth control. The pamphlet was described in court as obscene and Watts pleaded guilty. He was released and his sentence suspended. Condemned for not carrying the case through, Watts resigned from the NSS. Some secularists at the time hesitated to champion birth control. Some even opposed it, and they followed Watts and Holyoake out of the Society to found the British Secular Union. Charles Bradlaugh and Mrs. Besant started their own Freethought Publishing Co. and published the Knowlton pamphlet.

Annie Besant

The Fruits of Philosophy

1878

Bradlaugh and Besant Prosecuted for Publishing an ‘Obscene Libel’

The publication and distribution of The Fruits of Philosophy; or the Private Companion of Young Married Couples by Charles Knowlton resulted in Bradlaugh and Besant being prosecuted for publishing an ‘obscene libel’. The case became a cause célèbre that revealed the full scale of Victorian prejudice. The jury were unanimous in the opinion that the book was calculated to deprave public morals. Bradlaugh and Besant, however, escaped imprisonment on a technicality. The overall effect of the trial was to make large numbers of people aware of the potential available for better planning of the size of their families. The new Knowlton edition sold 100,000 in three months, and another birth control pamphlet by Mrs. Besant sold 150,000. Edward Truelove was then jailed for four months for selling birth control pamphlets. Secularists raised funds for his defence and petitioned the government, unsuccessfully, regarding his 7-month sentence. Mrs. Besant was deprived of the custody of her child because of her views. When, much later, she became a theosophist, she rejected birth control.

1880

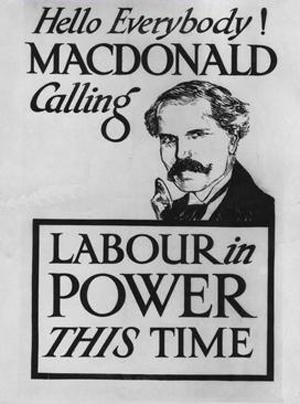

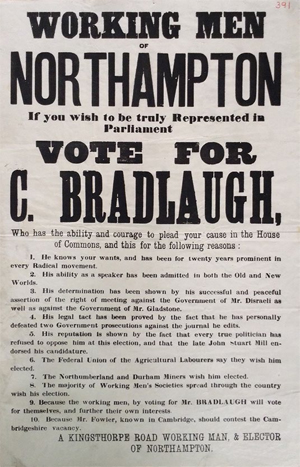

Bradlaugh elected in Northampton, rejected in Parliament

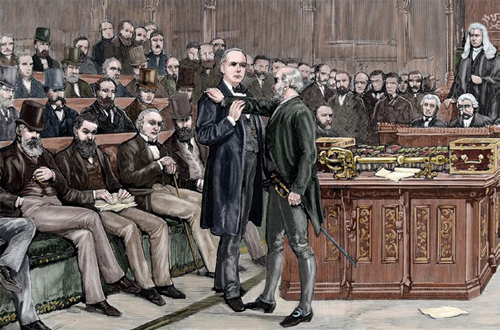

After being elected as MP for Northampton, Bradlaugh was prevented from taking his seat. His request to affirm instead of taking the religious oath was refused by the Commons; and a committee recommendation that he affirm at his legal peril was rejected by the House. Nevertheless, he presented himself to be sworn in and was faced with fierce hostility from MPs and parliamentary officials. Refusing to withdraw he was removed to the Clock Tower under Big Ben and there detained.

NSS membership reached 6,000 and there was an untold increase in outside support. Secular funerals were legalised.

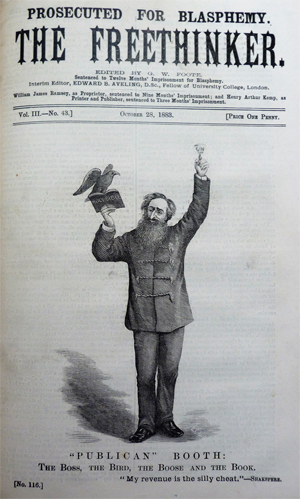

1881

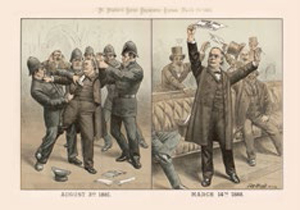

Bradlaugh denied his seat again, despite repeated attempts to claim it

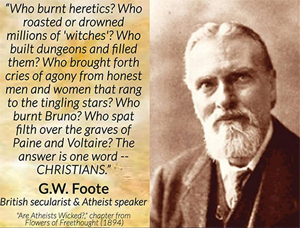

There was a nationwide controversy over Bradlaugh who, on one occasion, was forcibly ejected from the House of Commons by ten policemen and others in a brutal struggle. Mrs. Besant had to restrain Bradlaugh’s assembled supporters from reacting violently. Gladstone moved that if Bradlaugh tried to vote in parliament, he would be prosecuted. Bradlaugh voted and was taken to court. His Northampton seat was declared vacant. This gave new strength and impetus to the secularist campaign for affirmation rights. The NSS acquired the support of a new organ, The Freethinker, edited by G. W. Foote. Among the speakers at the opening of the Leicester Secular Hall (which is still extant) were Bradlaugh and Mrs. Besant.

Bradlaugh and the Bigots – a cartoon in support of Bradlaugh, 1881

1882

Bradlaugh re-elected and still debarred

Bradlaugh was again returned for Northampton but was again denied his parliamentary seat. He was, at the time, vigorously opposing grants to the royal family.

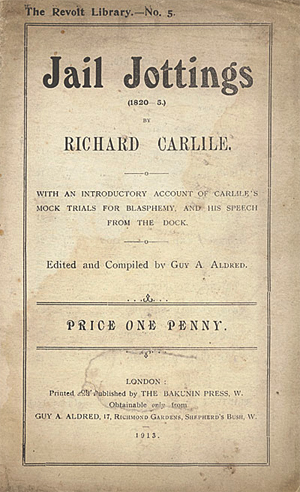

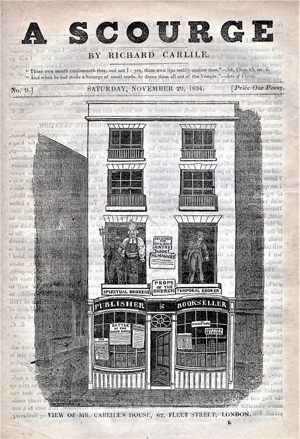

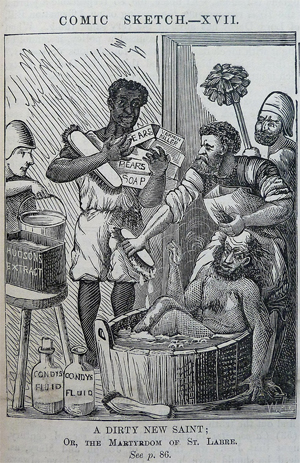

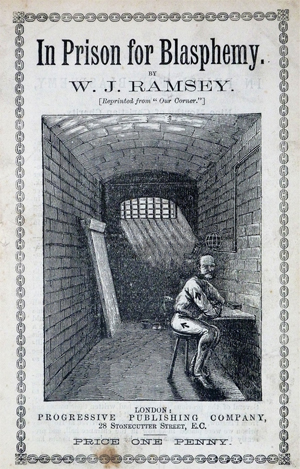

After much religion-baiting and deliberate provocations, The Freethinker was prosecuted for blasphemy. Its editor G.W. Foote was imprisoned for 12 months. Foote’s famous reply to the judge as he passed sentence was: “My lord, the sentence is worthy of your creed.” Bradlaugh foiled an attempt to implicate him. He gained a separate trial and was acquitted; a conviction would have quashed his ability to stand for Parliament. There was now an even greater agitation by secularists for the abolition of the blasphemy laws. There was also a petition for Foote, signed by many eminent scientists and literary men and even some clergymen. Foote was to later become a notable president of the NSS.

Bradlaugh at the Bar of the House of Commons

1885

Bradlaugh elected again as NSS grows

Bradlaugh was elected again as MP by the voters of Northampton. In his non-stop activity he was urging votes for women, drawing up a radical programme, and serving as Vice- President of the Sunday League, which was being materially aided by the NSS. Bradlaugh’s fame was growing and he was addressing overflowing meetings around the country, speaking on one occasion to 3,000 at Leicester. NSS membership hit a new peak; there were 102 branches and five independent secular societies, and regular outdoor stations at 20 places in London alone. Mrs. Besant was now in the Fabian Society, combining secularist with socialist activity.

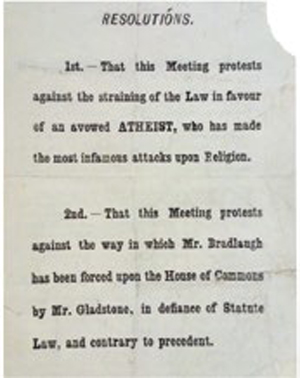

Protest Meeting against Affirmations Bill

RESOLUTIONS.

1st. That this Meeting protests against the straining of the Law in favour of an avowed ATHEIST, who has made the most infamous attacks upon Religion.

2nd. That this Meeting protests against the way in which Mr. Bradlaugh has been forced upon the House of Commons by Mr. Gladstone, in defiance of Statute Law, and contrary to precedent.

1886

Bradlaugh finally takes his seat in Parliament

Bradlaugh was finally allowed to takes his parliamentary seat on oath, and being busily engaged in Parliament, allowed much of the NSS leadership to devolve on GW Foote. A bill for the abolition of the blasphemy laws failed. There was also increased agitation for disestablishment.

“I had never heard of Mr Bradlaugh before. He is a massive man, physically and intellectually, and after listening to one or two of his speeches I was not surprised at the influence he has acquired here. A more effective speaker at electioneering meetings I have never come across in America or England. After calmly replying in detail to some of the trash that forms the staple of Conservative oratory, he raises his voice until the very walls echo with it and winds up with a fierce appeal to the electors to do their duty.”

-- Henry Labouchere, fellow Northampton MP

Bradlaugh arrested for refusing to leave the Chamber of Commons

WORKING MEN OF NORTHAMPTON

If you wish to be truly Represents in Parliament

VOTE FOR C. BRADLAUGH,

Who has the ability and courage to plead your cause in the House of Commons, and this for the following reasons:

1. He knows your wants, and has been for twenty years prominent in every Radical movement.

2. His ability as a speaker has been admitted in both the Old and New Worlds.

3. His determination has been shown by his successful and peaceful assertion of the right of meeting against the Government of Mr. Disraeli as well as against the Government of Mr. Gladstone.

4. His legal tact has been proved by the fact that he has personally defeated two Government prosecutions against the journal he edits.

5. His reputation is shown by the fact that every true politician has refused to oppose him at this election, and that the late John Stuart Mill endorsed his candidature.

6. The Federal Union of the Agricultural Labourers say they wish him elected.

7. The Northumberland and Durham Miners wish him elected.

8. The majority of Working Men's Societies spread through the country wish his election.

9. Because the working men, by voting for Mr. BRADLAUGH will vote for themselves, and further their own interests.

10. Because Mr. Fowler, known in Cambridge, should contest the Cambridgeshire vacancy.

A KINGSTHORPE ROAD WORKING MAN & ELECTOR OF NORTHAMPTON.

Bradlaugh triumphs with the passing of the Oaths Act in 1888

1888

Oaths Act

After a six year struggle and four byelection victories, Bradlaugh became very active in parliament. He was instrumental in bringing about a change in the law, giving all MPs the right to affirm rather than swear a religious oath. Today, any MP or Member of the House of Lords who objects to swearing an oath can make a solemn affirmation instead. Punch (the Private Eye of its day) wrote: “Not many years ago members crowded the lobbies to see Bradlaugh kicked downstairs. Now they throng the benches to hear him.”

1889'

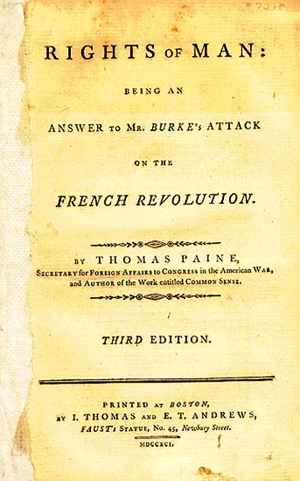

Bradlaugh tries to abolish the blasphemy law

Despite having Prime Ministerial support, Bradlaugh’s blasphemy bill failed at the second reading. He was suffering kidney disease and his health was failing. Despite this he travelled to speak to the fifth Indian National Congress in Bombay. He became known as “the member for India”, being ahead of his time in advocating Indian self-determination. Annie Besant then converted to the mystical religion of theosophy and gradually moved away from secularism.

1890

Bradlaugh resigns as NSS president

Bradlaugh resigned as president of the NSS in 1890 due to ill-health and G. W. Foote was unanimously acclaimed as the new president. At the same time, a young man of 22 from Leicester called Chapman Cohen was lecturing in public spaces for the NSS. By 1890 there were four independent secular societies, 57 NSS branches in London and district, 20 in the south (one in Jersey), 33 in the Midlands, and 115 in the northern counties, with heavy concentrations in Lancashire, the West Riding and Durham. There were also 12 in Scotland, four in Ireland and seven in Wales.

NSS members pay their respects to Bradlaugh at his grave in Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking

1891

Bradlaugh dies

Ironically, Charles Bradlaugh died just as the House of Commons expunged the resolutions that had forbidden him from taking his seat for so long. He was buried at Brookwood Cemetery in the presence of thousands of his admirers. One of them was Mahatma Gandhi, then aged 21.

1892

Attempt to legalise bequests to secular organisations

The NSS supported a bill which would legalise freethought bequests, but it failed.

Unveiling of a statue commemorating Bradlaugh in Northampton, June 25 1894

1894

NSS calls for end of hereditary House of Lords

The NSS joined the agitation for the abolition of the hereditary House of Lords.

Hypatia Bradlaugh’s life of her father was published.

1895

Secular education again

The NSS issued a manifesto on secular education. It also sued the publishers of a pamphlet alleging that a class was conducted at the Hall of Science (the NSS Headquarters) “teaching boys unnatural vice”.

1898

Attempt to protect bequests

The Secular Society Ltd. was formed by GW Foote to safeguard bequests to freethought organisations.

1906

NSS supports votes for women

Many secularists supported the suffragette cause and there was even a term for men who supported the campaigns: “suffra-gent”. The first of these to be sent to jail was Bayard Simmons.

1907

Secular Education League

The Secular Education League set up by liberal Christians, ethicists, rationalists and secularists. The NSS was a leading member of this alliance with G. W. Foote and Chapman Cohen on the Executive. There was a Trafalgar Square demonstration under the auspices of the Social Democratic Federation, with the NSS strongly represented and Foote a main speaker. The League’s aim was to abolish sectarian schools and establish a secular education system – an ambition still being pursued by the NSS today. The League was wound up in 1964, with its aims unrealised. One of its leading lights, the Rev. J Hirst Hollowed, wrote in 1907: “The State school must be restricted to national and moral education, and religious teaching of all kinds must be thrown upon the Churches, in private hours, at their own cost, and by their own agents”.

1911

Equal rights demanded in Birmingham

A campaign was launched in Birmingham demanding the right to hire the Town Hall for secularist meetings on the same basis as Christian bodies could for their purposes. Plans for secular meetings were often frustrated by refusals to hire halls; this was why so many of the secular societies around the country built their own halls.

Later that year, J. W. Gott was imprisoned for blasphemy.

1915

New president for the NSS

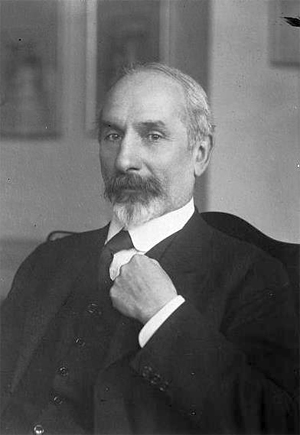

After the death of G. W. Foote (b. 1850) many tributes were published in The Freethinker and other journals. Chapman Cohen took over as editor of The Freethinker and became President of the NSS.

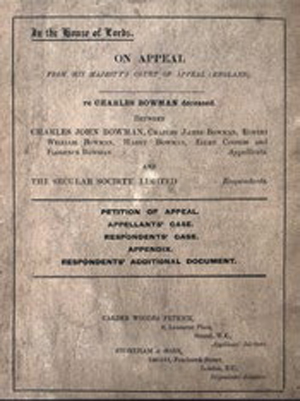

Bowman v. Secular Society – a landmark legal case – was started. It became one of the most important religious legal cases in England. It concerned a bequest from Charles Bowman to the Secular Society Ltd that was disputed by Mr Bowman’s next of kin. They argued that the objects of the Society were unlawful insofar as they constituted a blasphemous libel and therefore the gift was contrary to public policy and invalid.

1916

Religion in the armed forces

The NSS energetically protested against compulsory religious observances in the Army and Navy.

“The process of secularisation arises not from the loss of faith but from the loss of social interest in the world of faith. It begins the moment men feel that religion is irrelevant to the common way of life and that society as such has nothing to do with the truths of faith.”

-- Christopher Henry Dawson

1917

Bowman case won

Judgment in the Bowman case was given in favour of the Secular Society Ltd. Mr. Justice Joyce, in a brief judgment, said the case must be decided by law, and he did not find anything in the Memorandum of the Secular Society subversive of morality or contrary to law. Consequently the bequest was good. The trial established that blasphemous libel existed only in scurrilous or profane attacks on Christianity, not in temperate or reasoned criticism and a denial of the truth of Christianity. It did not render a person or organisation unable to claim the benefit and protection of civil law.

Court papers for Bowman v The Secular Society

1920

The right to sell literature in London parks

The NSS, along with other organisations, had endured a four-year struggle for the right to sell literature in the London parks. The collective protests were organised by Miss E. Vance, the NSS’s Secretary, supported by Harry (later Lord) Snell. The campaign succeeded. The NSS created a Trust Deed.

Married Love and Love in Marriage

1921

First birth control clinic opened

Marie Stopes opened the first birth control clinic in the world, in Holloway, north London. The Marie Stopes Foundation now supplies contraceptive advice and safe abortion in 38 countries around the world. It would not be until 1930 that the Anglican Church came grudgingly to accept contraception in certain circumstances.

1922

The struggle against blasphemy laws continues

Chapman Cohen was on the Executive Committee of The Society for the Abolition of the Blasphemy Laws. J.W. Gott was imprisoned for blasphemy for the fourth time: he died shortly after his release from prison in 1923.

1925

Agitation against blasphemy and creationism grows further

Secularists’ agitation for the repeal of the blasphemy laws gains support from some peers in the House of Lords. An anthropologist, Sir Arthur Keith, is welcomed by secularists as a spirited defender of Darwinism against Creationism.

1926

Cohen causes a stir

Pressure by freethinkers induces the Manchester Evening News to invite Chapman Cohen’s participation in a feature “Have We Lost Faith?” and a long controversy ensues which further raises the NSS’s profile.

1927

Bertrand Russell delivers his famous speech

Bertrand Russell lectured for the NSS at Battersea Town Hall on “Why I am not a Christian”. The lecture became very famous and was later published as a booklet and is still in print today.

"Why I am not a Christian"

1928

BBC’s religious obsession causes resentment

Secularists strenuously protested to the BBC about the gross religious privileges on the air. Sir John Reith (later to be Lord Reith), a supposedly pious, fulminating Christian, was Director General. He was later revealed to be a Nazi sympathiser.

1929

NSS lobbies election candidates

The NSS and the Rationalist Press Association (which still publishes the New Humanist) issued a joint circular containing a three-point questionnaire to election candidates on secular education, the blasphemy laws, and the BBC.

South Place Chapel was sold and Conway Hall erected in Red Lion Square, Holborn, London WC1 where the NSS still holds its AGMs. It is owned by the Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly known as South Place Ethical Society, after its original location near London’s Moorgate.

The attempt to impose religious belief on children should be resisted. Religious doctrine is arbitrary and entirely the province of those who wish to maintain such views as they find adequate to their needs. It is entirely unacceptable, however, that doctrine should be foisted upon the young as a matter of duty in the course of their education. I welcome the campaign against compulsory chapel and religious coercion in our schools.

-- Bertand Russell

1930

BBC dedicates itself to Almighty God

A plaque was unveiled at BBC Broadcasting House in London reading: “This temple of the Arts and Muses is dedicated to Almighty God by the first governors of broadcasting in the year 1931. It is their prayer that good seed sown may bring forth a good harvest and that all things hostile to peace and purity may be banished from this house and that the people inclining their ear to whatsoever things are beautiful and honest and of good report, may tread the path of wisdom and uprightness.” Director General Lord Reith was puritanical in public but was later revealed by his daughter to have been in private an adulterer and a tyrant.

1931

NSS rails against religion in schools and religious services in the BBC

Secularists condemned the political pandering to the churches over religious teaching in schools. They also pressed for the BBC to broadcast alternative programmes while religious services were on the air. They criticised, too, the government’s Sunday Performance Bill.

1932

More struggles for equal access

With echoes of the 19th century, the NSS was refused the hire of a lecture hall in Birkenhead following religious pressure on the owners. A court challenge followed, but was unsuccessful. In Durham, following an anti-NSS demonstration by students, the police attempted to forbid further secularist meetings on the site; the attempt failed.

Charles Bradlaugh 1833-1891

1933

Bradlaugh Centenary

The Bradlaugh Centenary was celebrated with meetings, a Commemoration Fund, a BBC talk (brief and unsatisfactory). A gramophone recording was made by Chapman Cohen of one of his lectures.

1934

NSS has a full year of campaigning and lecturing

Secularists protested against the Incitement to Disaffection Bill that made it an offence to endeavour to seduce a member of HM Forces from his “duty or allegiance to His Majesty”, thus expanding the ambit of the law. There was also its now-annual attack on the BBC. During the year, the NSS executive sponsored some 500 lectures, mostly open-air; the Dublin Branch NSS was under severe pressure from the Catholic Church.

1936

Another attempt to abolish blasphemy

Secularists condemned the new Sunday Trading Act. E. Thurtle, MP, attempted a blasphemy law repeal bill, which failed. Other bodies with which the NSS was then co-operating were the Society for the Abolition of Blasphemy Laws, the Secular Education League, the Society for the Abolition of Capital Punishment, the League of Nations Union and the National Peace Council. The NSS executive sponsors 542 meetings in the year.

1938

Catholic attempts to thwart Freethought congress fail

The NSS Annual Conference was given a civic reception by the Lord Provost and Corporation of Glasgow.

There was Catholic-inspired agitation to prevent the International Freethought Congress (later the World Union of Freethinkers) from meeting in London. There were petitions to the Home Secretary and questions were asked in the House. Despite all this, the event took place and was an enormous success. The NSS played a leading part.

1940

Religious tests for teachers opposed

The NSS helped resist the clerical agitation for religious tests for teachers, and attacked the arbitrary war regulations regarding religious oaths, church parades and the status of army chaplains.

1941

NSS hit during Blitz

The offices of the Freethinker, NSS and Secular Society Ltd. in Farringdon Street were destroyed by fire in an air raid. New offices were quickly established nearby at 2 Furnival Street, less than half a mile from the NSS’s offices today.

1944

Butler Act

The blurring of the distinction between education and religious inculcation in UK schools today is largely the legacy of the Church’s historical role and influence in education. The Education Act 1944, the ‘Butler Act’, created the ‘dual system’ which brought religious schools into the state-maintained sector. The 1944 Act decreed that the school day of all publicly-funded schools must begin with an act of “collective worship” – a law still in place to this day, despite the objections of secularists and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child.

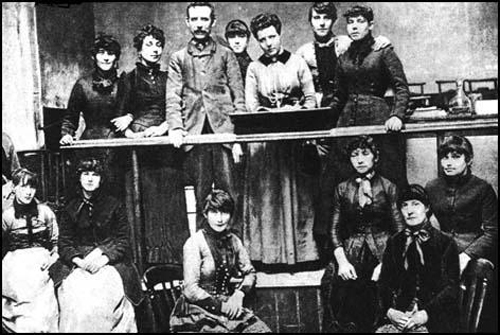

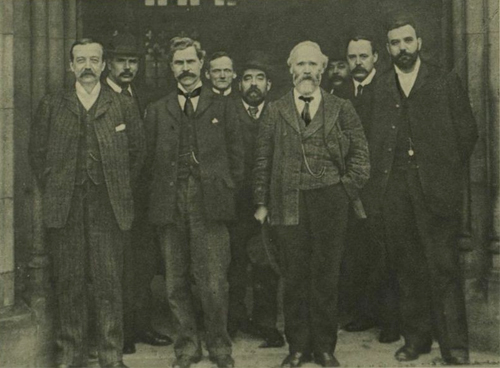

Participants at the NSS National conference in Nottingham in 1945

1949

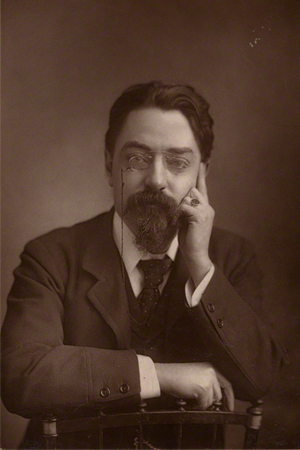

Chapman Cohen resigns

Chapman Cohen resigned the NSS presidency after 34 years: as an octogenarian he no longer felt able to be as active as he would wish. R. H. Rosetti was then made acting president.

1951

Marriage law reform supported

The NSS supported the Marriage Law Reform Society in an effort to rectify an anomaly in the Marriage Act: it exposed the Pope’s “mother or child” edict. Following the death of R. H. Rosetti (President), F. A. Ridley became acting President of the NSS and P. V. Morris its General Secretary.

1953

Republicanism reaffirmed

The NSS reaffirmed its adherence to republicanism and drew attention to the superstitious nature of the Coronation ceremony. Wreaths were laid on the Bradlaugh monument at Northampton during a gathering of secularists and rationalists. There was a large rise in NSS membership in two years. The NSS, Rationalist Press Association and Ethical Societies got together to form a Humanist Council for bringing pressure to bear on the BBC for a fair share of broadcasting.

A bill to remove Sunday trading restrictions was defeated.

1954

Chapman Cohen dies

Chapman Cohen (b. 1868) died. The NSS set about exposing the exploitative nature of the Billy Graham revivalist campaign that had arrived in London.

Chapman Cohen

1955

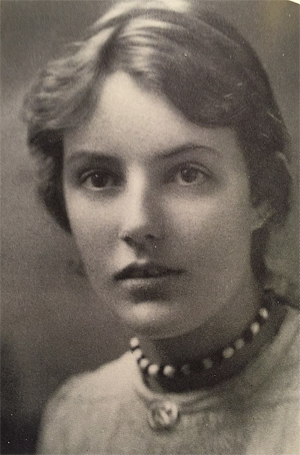

Margaret Knight smashes the barrier against atheists on the BBC

Broadcasting history was made when Mrs. Margaret Knight, of Aberdeen University, was allowed, in a series of talks on the BBC, to propose a Scientific Humanist, as opposed to a Christian, conception of morality. Her subsequent book took its title from her talks, Morals without Religion. There was enormous national publicity and controversy. Some national newspapers condemned Mrs Knight and defended Christian privilege in intemperate terms. She joined the NSS.

Colin McCall became NSS General Secretary.

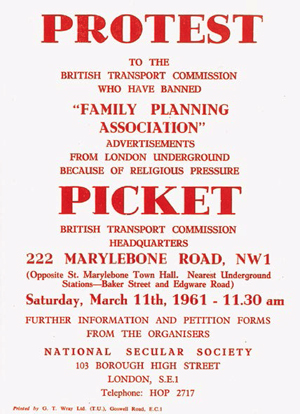

NSS members protest against London Transport’s family planning poster Ban in 1961

NSS organise picket over family planing poster ban 1961

PROTEST

TO THE BRITISH TRANSPORT COMMISSION WHO HAVE BANNED

"FAMILY PLANNING ASSOCIATION" ADVERTISEMENTS FROM LONDON UNDERGROUND BECAUSE OF RELIGIOUS PRESSURE

PICKET

BRITISH TRANSPORT COMMISSION HEADQUARTERS

222 MARYLEBONE ROAD, NW1

(Opposite St. Marylebone Town Hall, Nearest Underground Stations -- Baker Street and Edgware Road)

Saturday, March 11th, 1961 -- 11:30 a.m.

FURTHER INFORMATION AND PETITION FORMS FROM THEORGANISERS

NATIONAL SECULAR SOCIETY

103 BOROUGH HIGH STREET

LONDON, S.E.1

Telephone: HOP 2717

The NSS has been making the case for secular education since its inception

THE CASE FOR SECULAR EDUCATION

NSS Public Meeting Religion in Schools 1966[/i

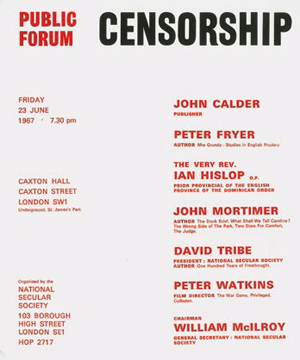

PUBLIC FORUM CENSORSHIP

JOHN CALDER. PUBLISHER

PETER FRYER. AUTHOR Mr. Grundy -- Studies in English Prudery

THE VERY REV. IAN HISLOP D.P. PRIOR PROVINCIAL OF THE ENGLISH PROVINCE OF THE DOMINICAN ORDER

JOHN MORTIMER. The Dock Brief, What Shall We Tell Caroline? The Wrong Side of the Park, Two Stars for Comfort, The Judge

DAVID TRIBE. PRESIDENT: NATIONAL SECULAR SOCIETY. AUTHOR One Hundred Years of Freethought

PETER WATKINS. FILM DIRECTOR. The War Game, Privilege, Culloden

CHAIRMAN WILLIAM McILROY. GENERAL SECRETARY: NATIONAL SECULAR SOCIETY

FRIDAY, 23 JUNE 1967, 7:30 p.m.

CAXTON HALL

CAXTON STREET

LONDON SWI

Organised by the

NATIONAL SECULAR SOCIETY

103 BOROUGH, HIGH STREET, LONDON SE1, HOP 2717

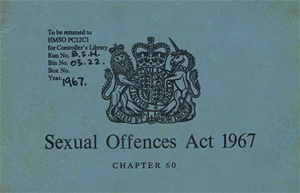

[i]Sexual Offences Act 1967, Chapter 60

1956

NSS protest against religious rates privileges

Mrs. Knight was the distinguished Guest of Honour at the NSS Annual Dinner. The NSS General Secretary recorded a two-minute talk at the invitation of a TV programme inquiring into the state of religion, but the talk was edited out of the show. Vigorous protests from the NSS ensued. The NSS was also protesting against the exemption of vicarages, presbyteries and manses from rates, and rate relief for the clergy. Margaret Knight appeared on TV to debate three Christian representatives.

1957

Wolfenden Report causes huge controversy

The Wolfenden Report, commissioned by the Government, called for homosexual acts to be decriminalised. Its publication caused a huge public reaction, but it took another decade before its recommendations were implemented. The NSS had long condemned the cruel anti-gay laws as one among many religion-based “injustices and abuses” and in its 1967 annual report the NSS said “homosexual toleration” would strengthen over time.

1961

Suicide legalised

The NSS was prominent in campaigning for the passing of The Suicide Act. Until this reform, attempted suicide was treated in law as a misdemeanour. Until 1823 suicide victims were buried at the village crossroads with a stake through their heart. From 1823 to 1882 they were buried in a unconsecrated part of the churchyard at night.

1963

David Tribe becomes president of the NSS, teaming up with Bill McIlroy

David Tribe, originally from Australia, was a very active NSS president from 1963 to 1971. He brought a new and modern approach to campaigning for secularism and was prominent in many of the major reform campaigns of the sixties. He was ably assisted by the redoubtable Bill McIlroy who was General Secretary 1963–77 (with a one-year break). Among Tribe’s many contributions was a pamphlet entitled Broadcasting, Brainwashing Conditioning – which continued, and enhanced, the long-running complaint about the disproportionate and deferential presence of religion on the BBC. This continues to the present, with a particular frustration at the continuance of Radio 4’s Thought for the Day as a purely religious preserve.

1964

NSS organises secular education month

In November 1964, with the support of playwright Harold Pinter and philosopher Bertrand Russell, the NSS organised Secular Education Month with meetings held in London, Glasgow, Inverness, Leicester, Manchester, Birmingham, Nottingham and Reading. The NSS has remained steadfast in its opposition to publicly funded ‘faith schools’ and continues to campaign against compulsory worship and faith-based admissions, instead advocating for secular, inclusive schools that are equally open and welcoming to all children, regardless of their religious and philosophical backgrounds.

ABOLISHED

1965

Challenge to theatre censorship

The Royal Court Theatre went ahead with performances of a play, Saved, by NSS Honorary Associate Edward Bond, despite it being banned by the theatre censor, the Lord Chamberlain. The resultant furore led to the Theatres Act of 1968 which abolished the role of the Lord Chamberlain.

The NSS had joined campaigns over several years calling for the abolition of the death penalty, which came about in 1965 with the passage of the Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act. The Race Relations Act was also passed in this year.

1967

Homosexuality decriminalised

In the face of much religious resistance, and after decades of struggle, the Sexual Offences Act was finally passed in 1967. It decriminalised sex in private between men over the age of 21. The NSS had long objected to the legal persecution of homosexuals.

Contraceptives were made available on the NHS.

1968

NSS enters right-to-die debate

An NSS working party produced a report “The Right to Die” aimed at reforming the law on assisted suicide. At that time those convicted of assisting a successful suicide could be charged with murder and jailed for 14 years. The many attempts at reforming the law had been thwarted by mainly religious opposition. NSS annual conference passed a resolution supporting voluntary euthanasia.

1969

Rights of ‘illegitimate children’ recognised

The Family Law Reform Act allowed people born outside marriage to inherit on the intestacy of either parent. It was not until 1987 that all legal distinctions between children born to married and unmarried parents were removed. The NSS had campaigned for this for many years.

NSS members at an Easter Monday rally in Hyde Park c.1970

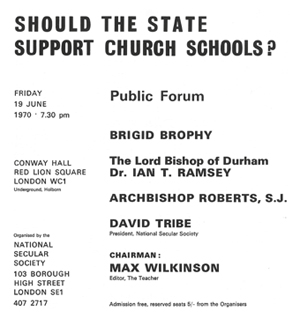

Should State Support Church Schools?

SHOULD THE STATE SUPPORT CHURCH SCHOOLS?

FRIDAY, 19 JUNE 1970, 7:30 p.m.

CONWAY HALL, RED LION SQUARE, LONDON, WC1

Public Forum

BRIGID BROPHY

The Lord Bishop of Durham

Dr. IAN T. RAMSEY

ARCHBISHOP ROBERTS, S.J.

DAVID TRIBE, President, National Secular Society

CHAIRMAN: MAX WILKINSON. Editor, The Teacher

Admission free, reserved seats 5 p. from the Organisers