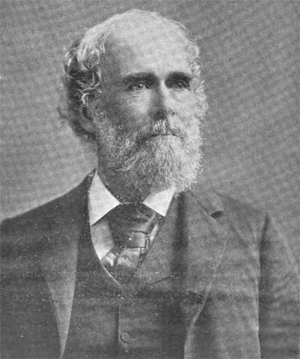

Herbert Spencerby Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

First published Sun Dec 15, 2002; substantive revision Tue Aug 27, 2019

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) is typically, though quite wrongly, considered a coarse social Darwinist. After all, Spencer, and not Darwin, coined the infamous expression “survival of the fittest”, leading G. E. Moore to conclude erroneously in Principia Ethica (1903) that Spencer committed the naturalistic fallacy. According to Moore, Spencer’s practical reasoning was deeply flawed insofar as he purportedly conflated mere survivability (a natural property) with goodness itself (a non-natural property).

Roughly fifty years later, Richard Hofstadter devoted an entire chapter of Social Darwinism in American Thought (1955) to Spencer, arguing that Spencer’s unfortunate vogue in late nineteenth-century America inspired

Andrew Carnegie and William Graham Sumner’s visions of unbridled and unrepentant capitalism. For Hofstadter, Spencer was an “ultra-conservative” for whom the poor were so much unfit detritus. His social philosophy “walked hand in hand” with reaction, making it little more than a “biological apology for laissez-faire” (Hofstadter, 1955: 41 and 46). But just because Carnegie interpreted Spencer’s social theory as justifying merciless economic competition, we shouldn’t automatically attribute such justificatory ambitions to Spencer. Otherwise, we risk uncritically reading the fact that Spencer happened to influence popularizers of social Darwinism into our interpretation of him. We risk falling victim to what Skinner perceptively calls the “mythology of prolepsis.”

Spencer’s reputation has never fully recovered from Moore and Hofstadter’s interpretative caricatures, thus marginalizing him to the hinterlands of intellectual history, though recent scholarship has begun restoring and repairing his legacy. Happily, in rehabilitating him, some moral philosophers have begun to appreciate just how fundamentally utilitarian his practical reasoning was. And some sociologists have likewise begun reassessing Spencer.

Intellectual history is forever being rewritten as we necessarily reinterpret its canonical texts and occasionally renominate marginalized thinkers for canonical consideration. Changing philosophical fashions and ideological agendas invariably doom us to reconstructing incessantly our intellectual heritage regardless the discipline. Take political theory instance. Isaiah Berlin’s understandable preoccupation with totalitarianism induced him to read T. H. Green and Bernard Bosanquet as its unwitting accomplices insofar as both purportedly equated freedom with dangerously enriched, neo-Hegelian fancies about self-realization. Regrettably, this ideological reconstruction of new liberals like Green and Bosanquet continues largely unabated (see Skinner, 2002: 16). But as our ideological sensitivities shift, we can now begin rereading them with changed prejudice, if not less prejudice. And the same goes for how we can now reread other marginalized, nineteenth-century English liberals like Spencer. As the shadow of European totalitarianism wanes, the lens through which we do intellectual history changes and we can more easily read our Spencer as he intended to be read, namely as a utilitarian who wanted to be a liberal just as much.

Like J. S. Mill, Spencer struggled to make utilitarianism authentically liberal by infusing it with a demanding principle of liberty and robust moral rights. He was convinced, like Mill, that utilitarianism could accommodate rights with independent moral force and yet remain genuinely consequentialist. Subtly construed, utilitarianism can effectively mimick the very best deontological liberalism.

Contents:1. First Principles

2.The Principles of Sociology

3. Spencer’s “Liberal” Utilitarianism

4. Rational Versus Empirical Utilitarianism

5. Political Rights

6. Conclusion

Bibliography

Primary Sources: Works by Spencer

Secondary Sources

Academic Tools

Other Internet Resources

Related Entries

1. First PrinciplesSpencer’s output was vast, covering several other disciplines besides philosophy and making it difficult to make sense of his philosophizing separate from his non-philosophical writing. And there is so much Spencer to make sense of, namely many thousand printed pages.[1] Besides ethics and political philosophy, Spencer wrote at length about psychology, biology and, especially, about sociology. Certain themes, not unexpectedly, run through much of this material. Coming to terms with Spencer and measuring his legacy requires expertise in all of these fields, which no one today has. Notwithstanding this caveat, it seems fair to say that next to ethics and political philosophy, Spencer’s lasting impact has been most pronounced in sociology. In many revealing respects, the latter grounds and orients the former. Hence, it seems best to discuss his sociology first before turning to his moral and political theory. But taking up his sociological theory, in turn, requires addressing, however briefly, the elemental axioms undergirding his entire “Synthetic Philosophy,” which consisted of The Principles of Biology (1864–7), The Principles of Psychology (1855 and 1870–2), The Principles of Sociology (1876–96), and The Principles of Ethics (1879–93).

First Principles was issued in 1862 as an axiomatic prolegomena to the synthetic philosophy, which came to a close with the publication of the 1896, final volume of The Principles of Sociology. Though disguised as mid-19th century speculative physics, First Principles is mostly metaphysics encompassing all inorganic change and organic evolution. The synthetic philosophy purports to illustrate in often maddening detail what follows from First Principles.

According to Spencer in First Principles, three principles regulate the universe, namely the Law of the Persistence of Force, the Law of the Instability of the Homogeneous and the Law of the Multiplicity of Effects. Though originally homogeneous, the universe is gradually becoming increasingly heterogeneous because Force or Energy expands un-uniformly. Homogeneity is unstable because Force is unstable and variable. And because of the Law of the Multiplicity of Effects, heterogeneous consequences grow exponentially, forever accelerating the tempo of homogeneity evolving into heterogeneity. Spencer postulates, though not always consistently, that the universe will eventually equilibrate, eventually dissolving towards homogeneity.

Using some of Spencer’s other terminology, the universe is relentlessly becoming more complex, forever subdividing into multifarious aggregates. As these aggregates become increasingly differentiated, their components become increasingly dissimilar speeding up the entire process and making the universe heterogeneous without end until equilibrium occurs. Or more parsimoniously: “Evolution is definable as a change from an incoherent homogeneity to a coherent heterogeneity, accompanying the dissipation of motion and integration of matter.” (Spencer, 1915: 291). For Spencer, then, all organic as well as inorganic phenomena were evolving, becoming evermore integrated and heterogeneous. As Spencer was to emphasize years later, this holds [true for] human social evolution no less:

Now, we propose in the first place to show, that this law of organic progress is the law of all progress. Whether it be in the development of the Earth, in the development of Life upon its surface, in the development of Society, of Government, of Manufactures, of Commerce, of Language, Literature, Science, Art, this same evolution of the simple into the complex, through successive differentiations, holds throughout. From the earliest traceable cosmical changes down to the latest results of civilization, we shall find that transformation of the homogeneous into the heterogeneous, is that in which progress essentially consists. (Spencer, vol. I, 1901: 10)[2]

In sum, societies were not only becoming increasingly complex, heterogeneous and cohesive. They were becoming additionally interdependent and their components, including their human members, more and more specialized and individuated.

2.The Principles of SociologyThe Principles of Sociology has often been considered seminal in the development of modern sociology both for its method and for much of its content. Replete with endless examples from the distant past, recent past and present, it speculatively describes and explains the entire arch of human social evolution.[3] Part V, “Political Institutions,” is especially relevant for understanding Spencer’s ethics. Together with his Principles of Ethics, “Political Institutions” crowns the synthetic philosophy. They are its whole point.[4]

On Spencer’s account, social evolution unfolds through four universal stages. These are 1) “primitive” societies characterized by casual political cooperation, 2) “militant” societies characterized by rigid, hierarchical political control, 3) “industrial” societies where centralized political hegemony collapses, giving way to minimally regulated markets and 4) spontaneously, self-regulating, market utopias in which government withers away. Overpopulation causing violent conflicts between social groups fuels this cycle of consolidation and reversal to which no society is immune.

More precisely, as embryonic kinship groups grow more numerous, they “come to be everywhere in one another’s way,” (Spencer, vol. II, 1876–93: 37). The more these primal societies crowd each other, the more externally violent and militant they become. Success in war requires greater solidarity and politically consolidated and enforced cohesion. Unremitting warfare fuses and formalizes political control, eradicating societies that fail to consolidate sufficiently. Clans form into nations and tribal chiefs become kings. As militarily successful societies subdue and absorb their rivals, they tend to stabilize and to “compound” and “recompound,” stimulating the division of labor and commerce. The division of labor and spread of contractual exchange transform successful and established “militant” societies into “negatively regulative industrial” societies prizing individual freedom and basic rights where the state recedes to protecting citizens against force and fraud at home and aggression from abroad. Other things being equal, a society in which life, liberty, and property, are secure, and all interests justly regarded, must prosper more than one in which they are not; and, consequently, among competing industrial societies there must be gradual replacing of those in which personal rights are imperfectly maintained, by those in which they are perfectly maintained.” (Spencer, vol. II, 1876–93: 608). And societies where rights are perfectly maintained will in due course confederate together in an ever-expanding pacific equilibrium. As noted previously, equilibrium is always unstable, risking dissolution and regression. Indeed by the end of his life, Spencer was far less sanguine about industrial societies avoiding war.[5]

Notwithstanding his increasing pessimism regarding liberal progress and international concord, the extent to which normative theorizing informs Spencer’s sociological theorizing is palpable. Sociology and ethics intertwine. We shall shortly see just how utilitarian as well as how individualistic both were.

Many recent interpreters of Spencer, especially sociologists, have insisted that his sociological theory and his ethics do not intertwine, that his sociology stands apart and that therefore we can discount his moral theory in our efforts to understand his legacy to social science. For instance, J. D. Y. Peel has argued that Spencer’s sociology is “logically independent of his ethics.” Jonathan H. Turner concurs, claiming that Spencer’s ethics and other ideological shortcomings “get in the way of viewing Spencer as a theorist whose [sociological] ideas have endured (if only by rediscovery).” For Turner, his “sociology is written so that these deficiencies can easily be ignored.” Robert Carneiro and Robert Perrin cite and reiterate Peel’s assessment.[6] And more recently, Mark Francis implies much the same, writing that Spencer’s theory of social change “operated on a different level than his moral theory.”.[7] But just because many years later we can get something out of his sociology while ignoring his ethics and, for that matter, anything else besides sociology that he wrote, we would err in thinking that we have correctly interpreted Spencer let alone thinking that we have correctly interpreted even just his sociology. It is one thing to discover how a past thinker seems to presage our present thinking on this matter or that, and it is another thing entirely to try to interpret a past thinker as best we can.

Nowhere does Spencer’s ethics and sociology entwine more palpably than in his Lamarckism, though how much Spencer borrowed from Lamarck as opposed to Darwin is contested. However, Peter J. Bowler has lately argued that both Spencer and Darwin believed that the inheritance of acquired characteristics and natural selection together drove evolution. For Bowler, it is no less mistaken to view Spencer as owing everything to Lamarck as it is to see him as owing very little to Lamarck.[8] Bowler’s assessment is supported by Spencer’s claims in two late essays from 1886 and 1893 entitled “The Factors of Organic Evolution” and “The Inadequacy of ‘Natural Selection.’”[9] The earlier essay alleges that evolution by natural selection declines in significance compared to use-inheritance as human mental and moral capacities develop. The latter gradually replaces the former as the mechanism of evolutionary change. “Factors of Organic Evolution” succinctly weaves together use-inheritance, associationist psychology, moral intuitionism and utility. Actions producing pleasure or pain tend to cause mental associations between types of actions and pleasures or pains. Sentiments of approval and disapproval also complement these associations. We tend naturally to approve pleasure-producing actions and disapprove pain-producing ones. Because of use-inheritance, these feelings of approval and disapproval intensify into deep-seated moral instincts of approval and disapproval, which gradually become refined moral intuitions.

To what extent Spencer’s sociology was functionalist has also been disputed. According to James G. Kennedy, Spencer created functionalism.[10] It would seem that regarding Spencer as a functionalist is another way of viewing him as, in contemporary normative terminology, a consequentialist. That is, social evolution favors social institutions and normative practices that promote human solidarity, happiness and flourishing.

Spencer’s reputation in sociology has faded. Social theorists remember him though most probably remember little about him though this may be changing somewhat. Moral philosophers, for their part, have mostly forgotten him even though 19th-century classical utilitarians like Mill and Henry Sidgwick, Idealists like T. H. Green and J. S. Mackenzie, and new liberals like D. G. Ritchie discussed him at considerable length though mostly critically. And 20th-century ideal utilitarians like Moore and Hastings Rashdall and Oxford intuitionists like W. D. Ross also felt compelled to engage him. Spencer was very much part of their intellectual context. He oriented their thinking not insignificantly. We cannot properly interpret them unless we take Spencer more seriously than we do.

3. Spencer’s “Liberal” UtilitarianismSpencer was a sociologist in part. But he was even more a moral philosopher. He was what we now refer to as a liberal utilitarian first who traded heavily in evolutionary theory in order to explain how our liberal utilitarian sense of justice emerges.

Though a utilitarian, Spencer took distributive justice no less seriously than Mill. For him as for Mill, liberty and justice were equivalent. Whereas Mill equated fundamental justice with his liberty principle, Spencer equated justice with equal liberty, which holds that the “liberty of each, limited by the like liberty of all, is the rule in conformity with which society must be organized” (Spencer, 1970: 79). Moreover, for Spencer as for Mill, liberty was sacrosanct, insuring that his utilitarianism was equally a bona fide form of liberalism. For both, respect for liberty also just happened to work out for the utilitarian best all things considered. Indefeasible liberty, properly formulated, and utility were therefore fully compossible.

Now in Spencer’s case, especially by The Principles of Ethics (1879–93), this compossibility rested on a complex evolutionary moral psychology combining associationism, Lamarckian use-inheritance, intuitionism and utility. Pleasure-producing activity has tended to generate biologically inheritable associations between certain types of actions, pleasurable feelings and feelings of approval. Gradually, utilitarianism becomes intuitive.[11] And wherever utilitarian intuitions thrive, societies tend to be more vibrant as well as stable. Social evolution favors cultures that internalize utilitarian maxims intuitively. Conduct “restrained within the required limits [stipulated by the principle of equal freedom], calling out no antagonistic passions, favors harmonious cooperation, profits the group, and, by implications, profits the average of individuals.” Consequently, “groups formed of members having this adaptation of nature” tend “to survive and spread” (Spencer, vol. II, 1978: 43). Wherever general utility thrives, societies thrive. General utility and cultural stamina go hand-in-hand. And general utility thrives best where individuals exercise and develop their faculties within the parameters stipulated by equal freedom.

In short, like any moral intuition, equal freedom favors societies that internalize it and, ultimately, self-consciously invoke it. And wherever societies celebrate equal freedom as an ultimate principle of justice, well-being flourishes and utilitarian liberalism spreads.

Spencer likewise took moral rights seriously insofar as properly celebrating equal freedom entailed recognizing and celebrating basic moral rights as its “corollaries.” Moral rights specify equal freedom, making its normative requirements substantively clearer. They stipulate our most essential sources of happiness, namely life and liberty. Moral rights to life and liberty are conditions of general happiness. They guarantee each individual the opportunity to exercise his or her faculties according to his or her own lights, which is the source of real happiness. Moral rights can’t make us happy but merely give us the equal chance to make ourselves happy as best we can. They consequently promote general happiness indirectly. And since they are “corollaries” of equal freedom, they are no less indefeasible than the principle of equal freedom itself.

Basic moral rights, then, emerge as intuitions too though they are more specific than our generalized intuitive appreciation of the utilitarian prowess of equal freedom. Consequently, self-consciously internalizing and refining our intuitive sense of equal freedom, transforming it into a principle of practical reasoning, simultaneously transforms our emerging normative intuitions about the sanctity of life and liberty into stringent juridical principles. And this is simply another way of claiming that general utility flourishes best wherever liberal principles are seriously invoked. Moral societies are happier societies and more vibrant and successful to boot.

Though Spencer sometimes labels basic moral rights “natural” rights, we should not be misled, as some scholars have been, by this characterization. Spencer’s most sustained and systematic discussion of moral rights occurs in the concluding chapter, “The Great Political Superstition,” of The Man Versus the State (1884). There, he says that basic rights are natural in the sense that they valorize “customs” and “usages” that naturally arise as a way of ameliorating social friction. Though conventional practices, only very specific rights nevertheless effectively promote human well-being. Only those societies that fortuitously embrace them flourish.

Recent scholars have misinterpreted Spencer’s theory rights because, among other reasons, they have no doubt misunderstood Spencer’s motives for writing The Man Versus the State. The essay is a highly polemical protest, in the name of strong rights as the best antidote, against the dangers of incremental legislative reforms introducing socialism surreptitiously into Britain. Its vitriolic, anti-socialist language surely accounts for much of its sometimes nasty social Darwinist rhetoric, which is unmatched in Spencer’s other writings notwithstanding scattered passages in The Principles of Ethics and in The Principles of Sociology (1876–96).[12]

Spencer’s “liberal” utilitarian credentials are therefore compelling as his 1863 exchange of letters with Mill further testifies. Between the 1861 serial publication of Utilitarianism in Fraser’s Magazine and its 1863 publication as a book, Spencer wrote Mill, protesting that Mill erroneously implied that he was anti-utilitarian in a footnote near the end of the last chapter, “Of the Connection Between Justice and Utility.” Agreeing with Benthamism that happiness is the “ultimate” end, Spencer firmly disagrees that it should be our “proximate” end. He next adds:

But the view for which I contend is, that Morality properly so-called – the science of right conduct – has for its object to determine how and why certain modes of conduct are detrimental, and certain other modes beneficial. These good and bad results cannot be accidental, but must be necessary consequences of the constitution of things; and I conceive it to be the business of moral science to deduce, from the laws of life and the conditions of existence, what kinds of action necessarily tend to produce happiness, and what kinds to produce unhappiness. Having done this, its deductions are to be recognized as laws of conduct; and are to be conformed to irrespective of a direct estimation of happiness or misery (Spencer, vol. II, 1904: 88–9).[13]

Specific types of actions, in short, necessarily always promote general utility best over the long term though not always in the interim. While they may not always promote it proximately, they invariably promote it ultimately or, in other words, indirectly. These action types constitute uncompromising, normative “laws of conduct.” As such, they specify the parameters of equal freedom. That is, they constitute our fundamental moral rights. We have moral rights to these action types if we have moral rights to anything at all.

Spencer as much as Mill, then, advocates indirect utilitarianism by featuring robust moral rights. For both theorists, rights-oriented utilitarianism best fosters general happiness because individuals succeed in making themselves happiest when they develop their mental and physical faculties by exercising them as they deem most appropriate, which, in turn, requires extensive freedom. But since we live socially, what we practically require is equal freedom suitably fleshed out in terms of its moral right corollaries. Moral rights to life and liberty secure our most vital opportunities for making ourselves as happy as we possibly can. So if Mill remains potently germane because his legacy to contemporary liberal utilitarian still inspires, then we should take better account of Spencer than, unfortunately, we currently do.

Spencer’s “liberal” utilitarianism, however, differs from Mill’s in several respects, including principally the greater stringency that Spencer ascribed to moral rights. Indeed, Mill regarded this difference as the fundamental one between them. Mill responded to Spencer’s letter professing allegiance to utilitarianism, observing that he concurs fully with Spencer that utilitarianism must incorporate the “widest and most general principles” that it possibly can. However, in contrast to Spencer, Mill protests that he “cannot admit that any of these principles are necessary, or that the practical conclusions which can be drawn from them are even (absolutely) universal” (Duncan, ed., 1908: 108).[14]

4. Rational Versus Empirical UtilitarianismSpencer referred to his own brand of utilitarianism as “rational” utilitarianism, which he claimed improved upon Bentham’s inferior “empirical” utilitarianism. And though he never labeled Mill a “rational” utilitarian, presumably he regarded him as one.

One should not underestimate what “rational” utilitarianism implied for Spencer metaethically. In identifying himself as a “rational” utilitarian, Spencer distanced himself decidedly from social Darwinism, showing why Moore’s infamous judgment was misplaced. Responding to T. H. Huxley’s accusation that he conflated good with “survival of the fittest,” Spencer insisted that “fittest” and “best” were not equivalent. He agreed with Huxley that though ethics can be evolutionarily explained, ethics nevertheless preempts normal struggle for existence with the arrival of humans. Humans invest evolution with an “ethical check,” making human evolution qualitatively different from non-human evolution. “Rational” utilitarianism constitutes the most advanced form of “ethical check[ing]” insofar as it specifies the “equitable limits to his [the individual’s] activities, and of the restraints which must be imposed upon him” in his interactions with others (Spencer, vol. I, 1901: 125–28).[15] In short, once we begin systematizing our inchoate utilitarian intuitions with the principle of equal freedom and its derivative moral rights, we begin “check[ing]” evolutionary struggle for survival with unprecedented skill and subtlety. We self-consciously invest our utilitarianism with stringent liberal principles in order to advance our well-being as never before.

Now Henry Sidgwick seems to have understood what Spencer meant by “rational” utilitarianism better than most, although Sidgwick didn’t get Spencer entirely right either. Sidgwick engaged Spencer critically on numerous occasions. The concluding of Book II of The Methods of Ethics (1907), entitled “Deductive Hedonism,” is a sustained though veiled criticism of Spencer.[16]

For Sidgwick, Spencer’s utilitarianism was merely seemingly deductive even though it purported to be more scientific and rigorously rational than “empirical” utilitarianism. However, deductive hedonism fails because, contrary to what deductive hedonists like Spencer think, no general science of the causes of pleasure and pain exists, insuring that we will never succeed in formulating universal, indefeasible moral rules for promoting happiness. Moreover, Spencer only makes matters worse for himself in claiming that we can nevertheless formulate indefeasible moral rules for hypothetically perfectly moral human beings. First of all, in Sidgwick’s view, since we can’t possibly imagine what perfectly moral humans would look like, we could never possibly deduce an ideal moral code of “absolute” ethics for them. Secondly, even if we could somehow conceptualize such a code, it would nevertheless provide inadequate normative guidance to humans as we find them with all their actual desires, emotions and irrational proclivities.[17] For Sidgwick, all we have is utilitarian common-sense, which we can, and should, try to refine and systematize according the demands of our changing circumstances.[18]

Sidgwick, then, faulted Spencer for deceiving himself in thinking that he had successfully made “empirical” utilitarianism more rigorous by making it deductive and therefore “rational.” Rather, Spencer was simply offering just another variety of “empirical” utilitarianism instead. Nevertheless, Spencer’s version of “empirical” utilitarianism was much closer to Sidgwick’s than Sidgwick recognized. Spencer not only shadowed Mill substantively but Sidgwick methodologically.

In the preface to the sixth edition of The Methods of Ethics (1901), Sidgwick writes that as he became increasingly aware of the shortcomings of utilitarian calculation, he became ever more sensitive to the utilitarian efficacy of common sense “on the ground of the general presumption which evolution afforded that moral sentiments and opinions would point to conduct conducive to general happiness…” (Sidgwick, 1907: xxiii). In other words, common sense morality is a generally reliable, right-making decision procedure because social evolution has privileged the emergence of general happiness-generating moral sentiments. And whenever common sense fails us with conflicting or foggy guidance, we have little choice but to engage in order-restoring, utilitarian calculation. The latter works hand-in-glove with the former, forever refining and systematizing it.

Now Spencer’s “empirical” utilitarianism works much the same way even though Spencer obfuscated these similarities by spuriously distinguishing between “empirical” and supposedly superior, “rational” utilitarianism. Much like Sidgwick, Spencer holds that our common sense moral judgments derive their intuitive force from their proven utility-promoting power inherited from one generation to the next. Contrary to what “empirical” utilitarians like Bentham have mistakenly maintained, we never make utilitarian calculations in an intuition-free vacuum. Promoting utility is never simply a matter of choosing options, especially when much is at stake, by calculating and critically comparing utilities. Rather, the emergence of utilitarian practical reasoning begins wherever our moral intuitions breakdown. Moral science tests and refines our moral intuitions, which often prove “necessarily vague” and contradictory. In order to “make guidance by them adequate to all requirements, their dictates have to be interpreted and made definite by science; to which end there must be analysis of those conditions to complete living which they respond to, and from converse with which they have arisen.” Such analysis invariably entails recognizing the happiness of “each and all, as the end to be achieved by fulfillment of these conditions” (Spencer, vol. I, 1978: 204).

“Empirical” utilitarianism is “unconsciously made” out of the “accumulated results of past human experience,” eventually giving way to “rational” utilitarianism which is “determined by the intellect” (Spencer, 1969: 279 ff.). The latter, moreover, “implies guidance by the general conclusions which analysis of experience yields,” calculating the “distant effects” on lives “at large” (Spencer, 1981: 162–5).

In sum, “rational” utilitarianism is critical and empirical rather than deductive. It resolutely though judiciously embraces indefeasible moral rights as necessary conditions of general happiness, making utilitarianism rigorously and uncompromisingly liberal. And it was also evolutionary, much like Sidgwick’s. For both Spencer and Sidgwick, utilitarian practical reasoning exposes, refines and systematizes our underlying moral intuitions, which have thus far evolved in spite of their under-appreciated utility. Whereas Spencer labeled this progress towards “rational” utilitarianism, Sidgwick more appropriately called this “progress in the direction of a closer approximation to a perfectly enlightened [empirical] Utilitarianism” (Sidgwick, 1907: 455).

Notwithstanding the undervalued similarities between their respective versions of evolutionary utilitarianism, Spencer and Sidgwick nevertheless parted company in two fundamental respects. First, whereas for Spencer, “rational” utilitarianism refines “empirical” utilitarianism by converging on indefeasible moral rights, for Sidgwick, systematization never ceases. Rather, systematizing common sense continues indefinitely in order to keep pace with the vicissitudes of our social circumstances. The best utilitarian strategy requires flexibility and not the cramping rigidity of unyielding rights. In effect, Spencer’s utilitarianism was too dogmatically liberal for Sidgwick’s more tempered political tastes.

Second, Spencer was a Lamarckian while Sidgwick was not. For Spencer, moral faculty exercise hones each individual’s moral intuitions. Being biologically (and not just culturally) inheritable, these intuitions become increasingly authoritative in succeeding generations, favoring those cultures wherever moral common sense becomes more uncompromising all things being equal. Eventually, members of favored societies begin consciously recognizing, and further deliberately refining, the utility-generating potency of their inherited moral intuitions. “Rational,” scientific utilitarianism slowly replaces common sense, “empirical” utilitarianism as we learn the incomparable value of equal freedom and its derivative moral rights as everyday utilitarian decision procedures.[19]

Their differences aside, Spencer was nonetheless as much a utilitarian as Sidgwick, which the latter fully recognized though we should hesitate labeling Spencer a classical utilitarian as we now label Sidgwick. Moreover, Sidgwick was hardly alone at the turn of the twentieth-century in depicting Spencer as fundamentally utilitarian. J. H. Muirhead viewed him as a utilitarian as did W. D. Ross as late as 1939. (Muirhead, 1897: 136; Ross, 1939: 59). Even scholars in Germany at that time read Spencer as a utilitarian. For instance, A. G. Sinclair viewed him as a utilitarian worth comparing with Sidgwick. In his 1907 Der Utilitarismus bei Sidgwick und Spencer, Sinclair concludes “Daher ist er [Spencer], wie wir schon gesagt haben, ein evolutionistischer Hedonist und nicht ein ethischer Evolutionist,” which we can translate as “Therefore he (Spencer) is, as we have already seen, an evolutionary hedonist and not an ethical evolutionist” (Sinclair, 1907: 49). So however much we have fallen into the erroneous habit of regarding Spencer as little invested with 19th-century utilitarianism, he was not received that way at all by his immediate contemporaries both in England and in continental Europe.

5. Political RightsNot only was Spencer less than a “social Darwinist” as we have come to understand social Darwinism, but he was also less unambiguously libertarian as some, such as Eric Mack and Tibor Machan, have made him out to be. Not only his underlying utilitarianism but also the distinction, which he never forswears, between “rights properly so-called” and “political” rights, makes it problematic to read him as what we would call a ‘libertarian’.

Whereas “rights properly so-called” are authentic specifications of equal freedom, “political rights” are not. They are interim devices conditional on our moral imperfection. Insofar as we remain morally imperfect requiring government enforcement of moral rights proper, political rights insure that government nevertheless remains mostly benign, never unduly violating moral rights proper themselves. The “right to ignore the state” and the right of universal suffrage are two essential political rights for Spencer. In Social Statics, Spencer says “we cannot choose but admit the right of the citizen to adopt a condition of voluntary outlawry.” Every citizen is “free to drop connection with the state – to relinquish its protection and to refuse paying for its support” (Spencer, 1970: 185). For Spencer, this right helps restrict government to protecting proper moral rights because it allows citizens to take their business elsewhere when it doesn’t.

However, Spencer eventually repudiated this mere political right. For instance, in his 1894 An Autobiography, he insists that since citizens “cannot avoid benefiting by the social order which government maintains,” they have no right to opt out from its protection (Spencer, 1904, vol. 1: 362). They may not legitimately take their business elsewhere whenever they feel that their fundamental moral rights are being ill-protected. Because he eventually repudiated the “right to ignore the state,” we should not interpret Spencer as he comes across in Nozick 1974 (p. 289–290, footnote 10, the text of which is on p. 350), where he is referenced in support of such a right.

Spencer’s commitment to the right of universal suffrage likewise wanes in his later writings. Whereas in Social Statics, he regards universal suffrage as a dependable means of preventing government from overreaching its duty of sticking to protecting moral rights proper, by the later Principles of Ethics he concludes that universal suffrage fails to do this effectively and so he abandons his support of it. He later concluded that universal suffrage threatened respect for moral rights more than it protected them. Universal suffrage, especially when extended to women, encouraged “over-legislation,” allowing government to take up responsibilities which were none of its business.

Spencer, then, was more than willing to modify political rights in keeping with his changing assessment of how well they secured basic moral rights on whose sanctity promoting happiness depended. The more he became convinced that certain political rights were accordingly counterproductive, the more readily he forsook them and the less democratic, if not patently libertarian, he became.

Likewise, Spencer’s declining enthusiasm for land nationalization (which Hillel Steiner has recently found so inspiring), coupled with growing doubts that it followed as a corollary from the principle of equal freedom, testify to his waning radicalism.[20] According to Spencer in Social Statics, denying every citizen the right to use of the earth equally was a “crime inferior only in wickedness to the crime of taking away their lives or personal liberties” (Spencer: 1970, 182.) Private land ownership was incompatible with equal freedom because it denied most citizens equal access to the earth’s surface on which faculty exercise and happiness ultimately depended. However, by The Principles of Ethics, Spencer abandoned advocating comprehensive land nationalization, much to Henry George’s ire. George, an American, had previously regarded Spencer as a formidable ally in his crusade to abolish private land tenure.

Now Spencer’s repudiation of the moral right to use the earth and the political right to ignore the state, as well as the political right of universal suffrage, undermines his distinction between rational and empirical utilitarianism. In forswearing the right to use the earth — because he subsequently became convinced that land nationalization undermined, rather than promoted general utility — Spencer betrays just how much of a traditional empirical utilitarian he was. He abandoned land nationalization not because he concluded that the right to use the earth did not follow deductively from the principle of equal freedom. Rather, he abandoned land reform simply because he became convinced that it was an empirically counterproductive strategy for promoting utility.

Even more obviously, by repudiating political rights like the “right to ignore the state” and universal suffrage rights, he similarly divulged just how much empirical utilitarian considerations trumped all else in his practical reasoning. Not only was Spencer not a committed or consistent libertarian, but he was not much of rational utilitarian either. In the end, Spencer was mostly, to repeat, what we would now call a liberal utilitarian who, much like Mill, tried to combine strong rights with utility though, in Spencer’s case, he regarded moral rights as indefeasible.

6. ConclusionAllan Gibbard has suggested that, for Sidgwick, in refining and systematizing common sense, we transform “unconscious utilitarianism” into “conscious utilitarianism.” We “apply scientific techniques of felicific assessment to further the achievement of the old, unconscious goal” (Gibbard in Miller and Williams, eds., 1982: 72). Spencer’s “liberal” utilitarianism was comparable moral science. Sidgwick, however, aimed simply at “progress in the direction of a closer approximation to a perfectly enlightened Utilitarianism” (Sidgwick, 1907: 455). Spencer, by contrast, had more grandiose aspirations for repairing utilitarianism. Merely moving towards “perfectly enlightened Utilitarianism” was scientifically under ambitious. Fully “enlightened” utilitarianism was conceptually accessible and perhaps even politically practicable. And Spencer had discovered its secret, namely indefeasible moral rights.

Spencer, then, merits greater esteem if for no other reason than that Sidgwick, besides Mill, took him so seriously as a fellow utilitarian worthy of his critical attention. Unfortunately, contemporary intellectual history has been less kind, preferring a more convenient and simplistic narrative of the liberal canon that excludes him.

Spencer’s “liberal” utilitarianism was bolder and arguably more unstable than either Mill or Sidgwick’s. He followed Mill investing utilitarianism with robust moral rights hoping to keep it ethically appealing without forgoing its systemic coherence. While the principle of utility retreats to the background as a standard of overall normative assessment, moral rights serve as everyday sources of direct moral obligation, making Spencer no less an indirect utilitarian than Mill. But Spencer’s indirect utilitarianism is more volatile, more logically precarious, because Spencer burdened rights with indefeasibility while Mill made them stringent but nevertheless overridable depending on the magnitude of the utility at stake. For Spencer, we never compromise basic rights let the heavens fall. But for Mill, the prospect of collapsing heavens would easily justify appealing directly to the principle of utility at the expense of respect for moral rights.

Now, critics of utilitarianism from William Whewell (1794–1866) to David Lyons more recently have taken Mill and subsequent liberal utilitarians to task for trying to have their utilitarian cake and eat their liberalism too. As Lyons argues with great effect, by imposing liberal juridical constraints on the pursuit of general utility, Mill introduces as a second normative criterion with independent “moral force” compromising his utilitarianism. He risks embracing value pluralism if not abandoning utilitarianism altogether. And if Mill’s liberal version of utilitarianism is just value pluralism in disguise, then he still faces the further dilemma of how to arbitrate conflicts between utility and rights. If utility trumps rights only when enough of it is at stake, we must still ask how much enough is enough? And any systematic answer we might give simply injects another normative criterion into the problematic logic of our liberal utilitarian stew since we have now introduced a third higher criterion that legislates conflicts between the moral force of the principle of utility and the moral force of rights.[21]

If these dilemmas hold for Mill’s utilitarianism, then the implications are both better and worse for Spencer. Though for Mill, utility always trumps rights when enough of the former is in jeopardy, with Spencer, fundamental rights always trump utility no matter how much of the latter is imperiled. Hence, Spencer does not need to introduce surreptitiously supplemental criteria for adjudicating conflicts between utility and rights because rights are indefeasible, never giving way to the demands of utility or disutility no matter how immediate and no matter how promising or how catastrophic. In short, for Spencer, basic moral rights always carry the greater, practical (if not formal) moral force. Liberalism always supersedes utilitarianism in practice no matter how insistently Spencer feigns loyalty to the latter.

Naturally, one can salvage this kind of utilitarianism’s authenticity by implausibly contending that indefeasible moral rights always (meaning literally without exception) work out for the utilitarian best over both the short and long-terms. As Wayne Sumner correctly suggests, “absolute rights are not an impossible output for a consequentialist methodology” (Sumner, 1987: 211). While this maneuver would certainly rescue the logical integrity of Spencer’s liberal version of utilitarianism, it does so at the cost of considerable common sense credibility. And even if it were miraculously true that respecting rights without exception just happened to maximize long-term utility, empirically demonstrating this truth would certainly prove challenging at best. Moreover, notwithstanding this maneuver’s practical plausibility, it would nevertheless seem to cause utilitarianism to retire a “residual position” that is indeed hardly “worth calling utilitarianism” (Williams in Smart and Williams, 1973: 135).

Whether Spencer actually envisioned his utilitarianism this way is unclear. In any case, insofar as he also held that social evolution was tending towards human moral perfectibility, he could afford to worry less and less about whether rights-based utilitarianism was a plausible philosophical enterprise. Increasing moral perfectibility makes secondary decision procedures like basic moral rights unnecessary as a utility-promoting strategy. Why bother with promoting general utility indirectly once we have learned to promote it directly with certainty of success? Why bother with substitute sources of stand-in obligation when, thanks to having become moral saints, act utilitarianism will fortunately always do? But moral perfectibility’s unlikelihood is no less plausible than the likelihood of fanatical respect for basic moral rights always working out for the utilitarian best.[22] In any case, just as the latter strategy causes utilitarianism to retire completely for practical purposes, so the former strategy amounts to liberalism entirely retiring in turn. Hence, Mill’s version of “liberal” utilitarianism must be deemed more compelling and promising for those of us who remain stubbornly drawn to this problematical philosophical enterprise.

Spencer’s rights-based utilitarianism nonetheless has much to recommend for it despite its unconventional features and implausible implications. Even more than Mill, he suggests how liberal utilitarians could attempt to moderate utilitarianism in other ways, enabling it to retain a certain measure of considerable ethical appeal. Spencer’s utilitarianism wears its liberalism not only by constraining the pursuit of utility externally by deploying robust moral rights with palpable independent moral force. It also, and more successfully, shows how utilitarians can liberalize their utilitarianism by building internal constraints into their maximizing aims. If, following Spencer, we make our maximizing goal distribution-sensitive by including everyone’s happiness within it so that each individual obtains his or her fair share, then we have salvaged some kind of consequentialist authenticity while simultaneously securing individual integrity too. We have salvaged utilitarianism as a happiness-promoting, if not a happiness-maximizing, consequentialism. Because everyone is “to count for one, nobody for more than one” not just as a resource for generating utility but also as deserving to experience a share of it, no one may be sacrificed callously without limit for the good of the rest.[23] No one may be treated as a means only but must be treated as an end as well.

Spencer’s utilitarianism also has much to recommend for it simply for its much undervalued importance in the development of modern liberalism. If Mill and Sidgwick are critical to making sense of our liberal canon, then Spencer is no less critical. If both are crucial for coming to terms with Rawls particularly, and consequently with post-Rawlsianism generally, as I strongly believe both are, then Spencer surely deserves better from recent intellectual history. Intellectual history is one of the many important narratives we tell and retell ourselves. What a shame when we succumb to scholarly laziness in constructing these narratives just because such laziness both facilitates meeting the pedagogical challenges of teaching the liberal tradition and answering our need for a coherent philosophical identity.

_______________

Bibliography

Primary Sources: Works by Spencer1851, Social Statics, Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, 1970.

1855, The Principles of Psychology, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

1862, First Principles, Williams and Norgate, 1915.

1864–1867, The Principles of Biology, 2 volumes, London: Williams and Norgate.

1868–74, Essays: Moral, Political and Speculative, 3 vols., London: Williams and Norgate, 1901.

1873, The Study of Sociology, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969.

1879–93, The Principles of Ethics, 2 volumes, Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1978.

1884, The Man Versus the State, Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1981.

1893, “The Inadequacy of ‘Natural Selection’,” The Contemporary Review, 63: 153–166, 439–456.

1897, “M. De Laveleye’s Error” in Various Fragments, New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1898.

1897, The Principles of Sociology, 3 volumes, New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1876–96.

1904, An Autobiography, 2 volumes, London: Williams and Norgate.

Secondary Sources

Den Otter, Sandra M., 1996, British Idealism and Social Explanation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Duncan, David, 1908, The Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer, London: Methuen and Co.

Francis, Mark, 2007, Herbert Spencer and the Invention of Modern Life, Stocksfield: Acumen.

Francis, M. & M. Taylor (eds.), 2015, Herbert Spencer: Legacies, London: Routledge.

Gibbard, Allan, 1982, “Inchoately Utilitarian Common Sense: The Bearing of a Thesis of Sidgwick’s on Moral Theory,” in Harlan B. Miller and William H. Williams, (eds.), The Limits of Utilitarianism, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gray, John, 1983, Mill on Liberty: A Defence, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

–––, 1989, “Mill’s and Other Liberalisms,” in John Gray, Liberalisms: Essays in Political Philosophy, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hoftstadter, Richard, 1955, Social Darwinism in American Thought, Boston: Beacon Press.

Huxley, T. H., 1893, “Evolutionary Ethics” in T. H. Huxley, Evolution and Ethics and Other Essays, New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1929.

Mill, J. S., 1861, Utilitarianism in John M. Robson (ed.), The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, 33 vols., Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969, vol. x.

Moore, G. E., 1903, Principia Ethica, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Muirhead, J. H., 1897, The Elements of Ethics, London: John Murray.

Nozick, Robert, 1974, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, New York: Basic Books.

Offer, John, 1994, “Introduction,” in John Offer (ed.), Herbert Spencer: Political Writings, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––, 2014, ‘Herbert Spencer,”, in W.J.Mander (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of British Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 257–284.

–––, 2010, Herbert Spencer and Social Theory, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Paxton, Nancy, 1991, George Eliot and Herbert Spencer, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Riley, Jonathan, 1988, Liberal Utilitarianism: Social Choice Theory and J. S. Mill’s Philosophy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ritchie, D. G., 1891, The Principles of State Interference in Peter P. Nicholson (ed.), Collected Works of D. G. Ritchie, 6 vols., Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1998.

Ross, W. D., 1939, Foundations of Ethics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schneewind, Jerome, 1977, Sidgwick’s Ethics and Victorian Moral Philosophy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sidgwick, Henry, 1902, Lectures on the Ethics of T. H. Green, Mr. Herbert Spencer and J. Martineau, London: Macmillan.

–––, 1907, The Methods of Ethics, 7th edition, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., 1981.

–––, 1880, “Mr. Spencer’s Ethical System,” Mind, 5(18): 216–226.

Sinclair, A. G., 1907, Der Utilitarismus bei Sidgwick und Spencer, Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Skinner, Quentin, 2002, “A Third Concept of Liberty,” London Review of Books, 24(7): 16–18.

Sumner, W. L., 1987, The Moral Foundations of Rights, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, Michael W., 2007, The Philosophy of Herbert Spencer, London: Continuum.

Weinstein, D., 1998, Equal Freedom and Utility: Herbert Spencer’s Liberal Utilitarianism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

–––, 2000, “Deductive Hedonism and the Anxiety of Influence,” Utilitas, 12(3): 329–346.

Williams, Bernard, 1973, “A Critique of Utilitarianism,” in J. C. C. Smart and Bernard Williams (eds.), Utilitarianism: For and Against, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, R. M., 1970, Mind, Brain and Adaptation in the Nineteenth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press.