Frederick Denison Mauriceby Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/14/20

To some of those who joined the [Fabian] Society in its early days Christian Socialism opened the way of salvation. The "Christian Socialist" [No. 1, June, 1883, monthly, 1d.; continued until 1891.] was established by a band of persons [

John Malcolm Forbes Ludlow] some of whom were not Socialist and others not Christian. It claimed to be the

spiritual child of the Christian Socialist movement of 1848-52, which again was Socialist only on its critical side, and constructively was merely Co-operative Production by voluntary associations of workmen. Under the guidance of the Rev. Stewart D. Headlam its policy of the revived movement was Land Reform, particularly on the lines of the Single Tax. The introductory article boldly claims the name of Socialist, as used by

[Frederick Denison] Maurice and

[Charles] Kingsley: the July number contains a long article by

Henry George. In September a formal report is given of the work of the Democratic Federation. In November Christianity and Socialism are said to be convertible terms, and in January, 1884, the clerical view of usury is set forth in an article on the morality of interest. In March Mr. H.H. Champion explains "surplus value," and in April we find a sympathetic review of the "Historic Basis of Socialism." In April, 1885, appears a long and full report of a lecture by

Bernard Shaw to the Liberal and Social Union. The greater part of the paper is filled with Land Nationalisation, Irish affairs—the land agitation in Ireland was then at its height—and the propaganda of

Henry George: whilst much space is devoted to the religious aspect of the social problem.

Sydney Olivier, before he joined the Fabian Society, was one of the managing group, and amongst others concerned in it were the Rev. C.L. Marson and the Rev. W.E. Moll. At a later period a Christian Socialist Society was formed; but our concern here is with the factors which contributed to the Fabian Society at its start, and it is not necessary to touch on other periods of the movement.

-- The History of the Fabian Society, by Edward R. Pease

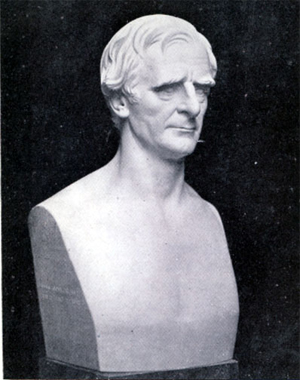

The Reverend F. D. Maurice

Born: John Frederick Denison Maurice, 29 August 1805, Normanston, Suffolk, England

Died: 1 April 1872 (aged 66), London, England

Other names: Frederick Denison Maurice

Spouse(s): Anna Barton (m. 1837; died 1845); Georgina Hare-Naylor (m. 1849)

Children: Sir John Frederick Maurice; Charles Edmund

Ecclesiastical career

Religion: Christianity (Anglican)

Church: Church of England

Ordained: 1834 (deacon)1835 (priest)

Academic background

Alma mater: Trinity Hall, Cambridge; Exeter College, Oxford

Influences:

Samuel Taylor Coleridge[1]

Germaine de Staël[2]

Thomas Erskine[3] Julius Hare[4] Edward Irving[5]

Plato[6]

William Wordsworth[2]

Academic work

Discipline: Theology

School or tradition: Christian socialism

Institutions: King's College, London; Working Men's College; University of Cambridge

Notable works: The Kingdom of Christ (1838)

Influenced: works The Kingdom of Christ (1838)

Influenced: Sir Percy Alden[7] Samuel Barnett[8] Phillips Brooks[9][10] James Baldwin Brown[11] Lewis Carroll[12] Lord Frederick Cavendish[13] William Collins Emma Cons[14] William Cunningham[15] Percy Dearmer[16] Frederic Farrar[17] P. T. Forsyth[9] Stewart Headlam[18] Gabriel Hebert[19] Octavia Hill[20] Henry Scott Holland[21] F. J. A. Hort[22] William Reed Huntington[23] J. R. Illingworth[24] Herbert Kelly[9]

Charles Kingsley[25][26] John Scott Lidgett[27] John Llewelyn Davies [cy][28] Arthur Lyttelton[24] George MacDonald[29] William Augustus Muhlenberg[30] H. Richard Niebuhr[9] Conrad Noel[31] Walter Pater[32] Michael Ramsey[33]

Vida Dutton Scudder[34]

Henry Sidgwick[35] Francis Herbert Stead[7]

William Temple[36] Alec Vidler[26][37] Brooke Foss Westcott[22] Arthur Winnington-Ingram[38]

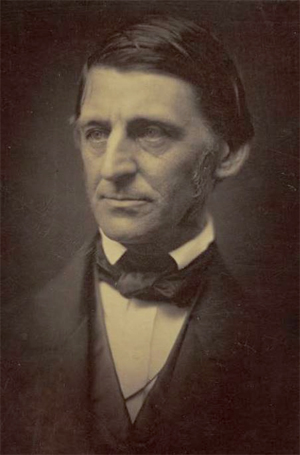

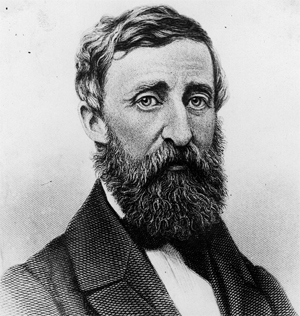

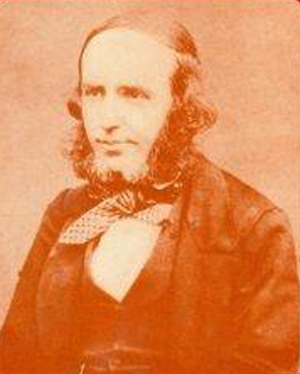

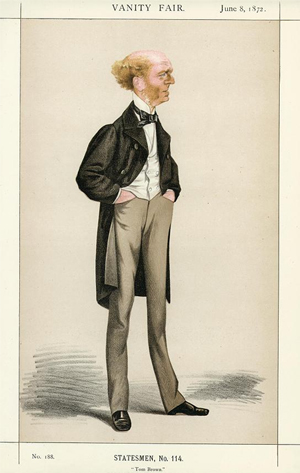

John Frederick Denison Maurice (1805–1872), known as F. D. Maurice, was an English Anglican theologian, a prolific author, and

one of the founders of Christian socialism. Since World War II, interest in Maurice has expanded.[39]

Early life and educationJohn Frederick Denison Maurice was born in Normanton, Suffolk, on 29 August 1805, the only son of Michael Maurice and his wife, Priscilla.

Michael Maurice was the evening preacher in a Unitarian chapel. Deaths in the family brought about changes in the family's "religious convictions" and "vehement disagreement" between family members.[40] Maurice later wrote about these disagreements and their effect on him:

My father was a Unitarian minister. He wished me to be one also. He had a strong feeling against the English Church, and against Cambridge as well as Oxford. My elder sisters, and ultimately my mother, abandoned Unitarianism. But they continued to be Dissenters; they were not less, but some of them at least more, averse from the English Church than he was. I was much confused between the opposite opinions in our household. What would surprise many, I felt a drawing towards the anti-Unitarian side, not from any religious bias, but because Unitarianism seemed to my boyish logic incoherent and feeble.[41]

Michael was "of no little learning" and gave his son his early education.[42] The son "appears to have been an exemplary child, responsive to teaching and always dutiful. He read a good deal on his own account, but had little inclination for games. Serious and precocious, he even at this time harboured ambitions for a life of public service."[40]

For his higher education in civil law, Maurice entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1823 that required no religious test for admissions though only members of the established church were eligible to obtain a degree.

With John Sterling Maurice founded the Apostles' Club. He moved to Trinity Hall in 1825. In 1826, Maurice went to London to read for the bar and returned to Cambridge where he obtained a first-class degree in civil law in 1827.[43][44]

During the 1827–1830 break in his higher education, Maurice lived in London and Southampton.

While in London, he contributed to the Westminster Review and made the acquaintance of John Stuart Mill. With Sterling he also edited the Athenaeum. The magazine did not pay and his father had lost money which entailed moving the family to a smaller house in Southampton and Maurice joined them. During his time in Southampton,

Maurice rejected his earlier Unitarianism and decided to be ordained in the Church of England.[40] Mill described Maurice and Sterling as representing a "a second Liberal and even Radical party, on totally different grounds from Benthamism."[45] Maurice's articles evince sympathy for Radicals such as Leigh Hunt and William Hazlitt, and he welcomed the "shattering of thrones, the convulsions of governments" that marked the end of the eighteenth century.[45] He likewise commended the Whig Henry Brougham's support for Catholic emancipation in England, but criticized him for relying too much on the aristocracy and not enough on the people.[45]Maurice entered Exeter College, Oxford, in 1830 to prepare for ordination. He was older than most of students, he was very poor and he "kept to himself, toiling at his books". However, "his honesty and intellectual powers" impressed others.[46] In March 1831, Maurice was baptised in the Church of England. After taking a second-class degree in November 1831, he worked as a "private tutor" in Oxford until his ordination as a deacon in January 1834 and appointment to a curacy in Bubbenhall near Leamington.[47] Being twenty-eight years old when he was ordained deacon, Maurice was older and with a wider experience than most ordinands. He had attended both universities and been active in "the literary and social interests of London". All this, coupled with his diligence in study and reading, gave Maurice a knowledge "scarcely paralleled by any of his contemporaries".[48] He was ordained as priest in 1835.[49]

Career and marriagesExcept for his 1834–1836 first clerical assignment, Maurice's career can be divided between his conflicted years in London (1836–1866) and his peaceful years in Cambridge (1866–1872)

For his first clerical assignment, Maurice served an assistant curacy in Bubbenhall in Warwickshire from 1834 until 1836. During his time in Bubbenhall, Maurice began writing on the topic of "moral and metaphysical philosophy". Writing on this topic by "revision and expansion" continued the rest of his life until the publication of Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy, 2 vols in 1871–1872, the year of his death.[50] Also, Maurice's novel Eustace Conway, begun c. 1830, was published in 1834 and was praised by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.[44]

In 1836, he was appointed chaplain of Guy's Hospital where he took up residence and "lectured the students on moral philosophy". He continued this post until 1860.[51][44] Maurice's public life began during his years at Guy's.[52]

In June 1837, Maurice met Anna Barton. They became engaged and were married on 7 October 1837."[40]

In 1838, the first edition of The Kingdom of Christ was published. It was "one of his most significant works." A second enlarged edition was published in 1842 and a third edition in 1883. For Maurice the signs of this kingdom are "the sacraments of baptism and the eucharist, to which must be added the creeds, the liturgy, the episcopate, and the scriptures—in fact, all the marks of catholicity as exemplified in the Church of England." The book was met with criticism when published, a criticism "that lasted throughout Maurice's career."[40]

LondonMaurice served as editor of the Educational Magazine during its entire 1839–1841 existence. He argued that "the school system should not be transferred from the church to the state." Maurice was elected professor of English literature and history at King's College, London, in 1840. When the college added a theological department in 1846, he became a professor there also. That same year Maurice was elected chaplain of Lincoln's Inn and resigned the chaplaincy at Guy's Hospital.[44]

In 1845, Maurice was made both the Boyle lecturer by the Archbishop of York's nomination and the Warburton lecturer by the Archbishop of Canterbury's nomination. He held these chairs until 1853.[40]

Maurice's wife, Anna, died on 25 March 1845, leaving two sons, one of whom was John Frederick Maurice who wrote his father's biography.[40]

Queen's CollegeDuring his London years, Maurice engaged in two lasting educational initiatives: founding Queen's College, London in 1848[53] and the Working Men's College in 1854.

In 1847, Maurice and "most of his brother-professors" at King's College formed a Committee on Education for the education of governesses. This committee joined a scheme for establishing a College for Women that resulted in the founding of Queen's College. Maurice was its first principal. The college was "empowered to grant certificates of qualification 'to governesses' and 'to open classes in all branches of female education'."[54]One of the early graduates of Queen's College who was influenced by Maurice was Matilda Ellen Bishop who became the first Principal of Royal Holloway College.[55]

On 4 July 1849, Maurice remarried, this time to Georgina Hare-Naylor.[40]

Dismissed from King's College"Maurice was dismissed from his professorships because of his leadership in the Christian Socialist Movement, and because of the supposed unorthodoxy of his Theological Essays (1853)."[56] His work The Kingdom of Christ had evoked virulent criticism. The publication of his Theological Essays in 1853 evoked even more and precipitated his dismissal from King's College. At the instigation of Richard William Jelf, the Principal of the College, the Council of the College, asked Maurice to resign. He refused and demanded that he be either "acquitted or dismissed." He was dismissed. To prevent the controversy from affecting Queen's College, Maurice "severed his relations" with it.[57]

The public and his friends were strongly in support of Maurice. His friends "looked up to him with the reverence due to a great spiritual teacher." They were devoted to him and wanted to protect Maurice against his opponents.[58]

Working Men's CollegeAlthough his relations with King's College and Queen's College had been severed, Maurice continued to work for the education of workers. In February 1854, he developed plans for a Working Men's College. Maurice gained enough support for the college by giving lectures that by 30 October 1854 the college opened with over 130 students. "Maurice became principal, and took an active part both in teaching and superintending during the rest of his life in London."[58]

Maurice's teaching led to some "abortive attempts at co-operation among working men" and to the more enduring Christian Socialism movement and the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations.[51]

In July 1860, in spite of controversy, Maurice was appointed to the benefice of the chapel of St. Peter's, Vere Street. He held the position until 1869.[58]

Cambridge University"On 25 October 1866 Maurice was elected to the Knightbridge professorship of casuistry, moral theology, and moral philosophy at [the University of] Cambridge."[40] This professorship was the "highest preferment" Maurice attained. Among his books he cited in his application, were his Theological Essays and What is Revelation? that had evoked opposition elsewhere. But at Cambridge, Maurice was "almost unanimously elected" to the faculty.[59] Maurice was "warmly received" at Cambridge, where "there were no doubts of his sufficient orthodoxy".[58]

While teaching at Cambridge, Maurice continued as the Working Men's College principal, though he was there less often. At first, he retained the Vere Street, London, cure which entailed a weekly rail trip to London to officiate at services and preach. When this proved too strenuous, upon medical advice, Maurice resigned this cure in October 1869. In 1870, by accepting the offer of St Edward's, Cambridge,[60] where he had "an opportunity for preaching to an intelligent audience" with few pastoral duties, albeit with no stipend.[40]

In July 1871 Maurice accepted the Cambridge preachership at Whitehall. "He was a man to whom other men, no matter how much they might differ from him, would listen."[61]

Royal CommissionerIn spite of declining health, in 1870 Maurice agreed to serve on the Royal Commission regarding the Contagious Diseases Act of 1871, and travelled to London for the meetings.[58] "The Commission consisted of twenty-three men, including ten parliamentarians (from both Houses), some clergy, and some eminent scientists (such as T.H. Huxley)."[62]

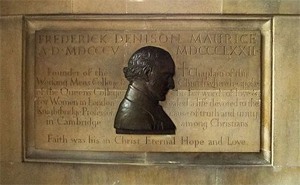

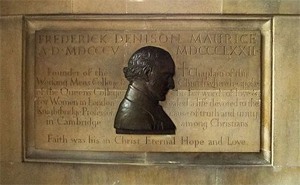

Dean Francis Close wrote a monograph about the proceedings of the royal commission. The issue was whether earlier acts legalising and policing prostitution for the armed forces should be repealed. Close quoted a commission member's speech to the House of Commons that praised Maurice as a "model Royal Commissioner". Close ended his monograph with these words: "Professor Maurice remained firmly and conscientiously opposed to the Acts to the very last."[63] Memorial in St Edward's Church, CambridgeFinal years

Memorial in St Edward's Church, CambridgeFinal yearsIn spite of terminal illness, Maurice continued giving his professorial lectures, trying to know his students personally and completing his Metaphysical and Moral Philosophy (2 vols., 1871–1872).[40] He also continued preaching (at Whitehall from November 1871 to January 1872 and two university sermons in November). His final sermon was 11 February 1872 in St Edward's. On 30 March he resigned from St Edward's.

Very weak and mentally depressed, on Easter Monday, 1 April 1872, after receiving Holy Communion, with great effort he pronounced the blessing, became unconscious and died.[58]

Conflicting opinions of Maurice's thinkingIn a letter of 2 April 1833 to Richard Chenevix Trench, Maurice lamented the current "spirit" of "conflicting opinions" that "cramps our energies" and "kills our life".[64] In spite of his lamenting "contradictory opinions," that term precisely described reactions to Maurice.

Maurice's writings, lectures, and sermons spawned conflicting opinions.

Julius Hare considered him "the greatest mind since Plato", but John Ruskin thought him "by nature puzzle-headed and indeed wrong-headed;"[51] while John Stuart Mill considered that “there was more intellectual power wasted in Maurice than in any other of my contemporaries”.[65]

Hugh Walker in a study of Victorian literature found other examples of conflicting opinions.[66]

• Charles Kingsley pronounced Maurice "a great and rare thinker".

• Aubrey Thomas de Vere compared listening to Maurice to "eating pea-soup with a fork".

• Matthew Arnold spoke of Maurice as "always beating the bush with profound emotion, but never starting the hare."

One important literary and theological figure who was favorably impressed by Maurice was Charles Dodgson, also known as Lewis Carroll. Dodgson wrote about attending morning and afternoon services at Vere Street at which Maurice preached both times with the comment, "I like his sermons very much".[67] Maurice held the benefice of the chapel of St. Peter's, Vere Street from 1860–1869.[58]

M. E. Grant Duff in his diary for 22 April 1855, wrote that he "went, as usual about this time, to hear F.D. Maurice preach at Lincoln's Inn. I suppose I must have heard him, first and last, some thirty or forty times, and never carried away one clear idea, or even the impression that he had more than the faintest conception of what he himself meant."[68]

John Henry Newman described Maurice as a man of "great power" and of "great earnestness". However, Newman found Maurice so "hazy" that he "lost interest in his writings."[69]

In the United States, The National Quarterly Review and Religious Magazine, Volume 38 (January 1879), contained this appreciation of Maurice. "Mr. Maurice's characteristics are well known and becoming every year more highly appreciated—broad catholicity, keeness of insight, powerful mental grasp, fearlessness of utterance and devoutness of spirit."[70]

Leslie Stephen in The English Utilitarians,Vol 3, John Stuart Mill. 1900., Wrote " Maurice is equally opposed to the sacerdotalism which makes the essence of religion consist in a magical removal of penalties instead of a 'regeneration' of the nature. He takes what may be vaguely called the 'subjective' view of religion, and sympathises with Schleiermacher's statement that piety is 'neither a knowing nor a doing, but an inclination and determination of the feelings' ".

Social activism Maurice (right) depicted with Thomas Carlyle in Ford Madox Brown's painting Work (detail)"The demand for political and economic righteousness is one of the principal themes of Maurice's theology."[71] Maurice practiced his theology by going "quietly on bearing the chief burthen of some of the most important social movements of the time."[72]

Maurice (right) depicted with Thomas Carlyle in Ford Madox Brown's painting Work (detail)"The demand for political and economic righteousness is one of the principal themes of Maurice's theology."[71] Maurice practiced his theology by going "quietly on bearing the chief burthen of some of the most important social movements of the time."[72]Living in London the "condition of the poor pressed upon him with consuming force." Working men trusted him when they distrusted other clergymen and the church.[51] Working men attended Bible classes and meetings led by Maurice whose theme was "moral edification."[40]

Christian socialismMaurice was affected by the "revolutionary movements of 1848", especially the march on Parliament, but

he believed that "Christianity rather than secularist doctrines was the only sound foundation for social reconstruction."[44]Maurice "disliked competition as fundamentally unchristian, and wished to see it, at the social level, replaced by co-operation, as expressive of Christian brotherhood." In 1849, Maurice joined other Christian socialist in an attempt to mitigate competition by the creation of co-operative societies.

He viewed co-operative societies as "a modern application of primitive Christian communism." Twelve cooperative workshops were to be launched in London. However, even with subsidy by Edward Vansittart Neale many turned out to be unprofitable.[40] Nevertheless, the effort effected lasting consequences as seen in the following sub-section on the "Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations"

In 1854, there were eight Co-operative Productive Associations in London and fourteen in the Provinces. These included breweries, flour mills, tailors, hat makers, builders, printers, engineers. Others were formed in the following decades. Some of them failed after several years, some lasted a longer time, some were replaced.[73]

Maurice's perception of a need for a moral and social regeneration of society led him into Christian socialism. From 1848 until 1854 (when the movement came to an end[56]), he was a leader of the Christian Socialist Movement.

He insisted that "Christianity is the only foundation of Socialism, and that a true Socialism is the necessary result of a sound Christianity."[74]

Maurice has been characterized as "the spiritual leader" of the Christian socialists because he was more interested in disseminating its theological foundations than "their practical endeavours."[58] Maurice once wrote,

Let people call me merely a philosopher, or merely anything else…. My business, because I am a theologian, and have no vocation except for theology, is not to build, but to dig, to show that economics and politics … must have a ground beneath themselves, and that society was not to be made by any arrangements of ours, but is to be regenerated by finding the law and ground of its order and harmony, the only secret of its existence, in God.[75]

Society for Promoting Working Men's AssociationsEarly in 1850 the Christian socialists started a working men's association for tailors in London, followed by associations for other trades. To promote this movement, a Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations (SPWMA) was founded with Maurice as a founding member and head of its a "central board". At first, the SPWMA's work was merely propagating the idea of associations by publishing tracts. Then

it undertook the practical project of establishing the Working Men's College because educated workers were essential for successful co-operative societies. With that ingredient more of the associations succeeded; others still failed or were replaced by a later "cooperative movement. The lasting legacy of the Christian socialists was that, in 1852, they influenced the passage of an act in Parliament which gave "a legal status to co-operative bodies" such as working men's associations. The SPWMA "flourished in the years from 1849 to 1853, or thereabouts."[58][76]

The original mission of the Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations was "to diffuse the principles of co-operation as the practical application of Christianity to the purposes of trade and industry." The goal was forming associations by which working men and their families could enjoy the whole produce of their labour.[77]In testimony from representatives of "Co-operative Societies" during 1892–1893 to the Royal Commission on Labour for the House of Commons, one witness applauded the contribution of Christian socialists to the "present cooperative movement" by their formulating the idea in the 1850s. The witness specifically cited "

[Frederick Denison] Maurice,

[Charles] Kingsley,

[John Malcolm Forbes] Ludlow, Neale, and

[Thomas] Hughes."[78]

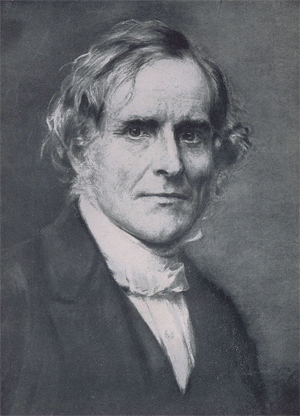

Legacy 1854 portrait of Maurice by Jane Mary Hayward

1854 portrait of Maurice by Jane Mary HaywardThat Maurice left a legacy that would be valued by many was harbingered by responses to his death. "Crowds following his remains to their last resting place, and around the open grave there stood men of widely different creeds, united for the moment by the common sorrow and their deep sense of loss. From pulpit and press, from loyal friends and honest opponents, the tribute to the worth of Mr. Maurice was both sincere and generous."[79]

Personal legacyMaurice's close friends were "deeply impressed with the spirituality of his character".

His wife observed that whenever Maurice was awake in the night, he was "always praying." Charles Kingsley called him "the most beautiful human soul whom God has ever allowed me to meet with."[51]Maurice's life comprised "contradictory elements".[51]

• Maurice was a man "of peace, yet his life was spent in a series of conflicts".

• He was a man "of deep humility, yet so polemical that he often seemed biased".

• He was a man "of large charity, yet bitter in his attack upon the religious press of his time".

• He was "a loyal churchman who detested the label Broad yet poured out criticism upon the leaders of the Church".

• He was a man of "a kindly dignity" combined with "a large sense of humour".

• He possessed "an intense capacity for visualizing the unseen".

Teaching legacyAs a professor at King's College and at Cambridge, Maurice attracted "a band of earnest students" to whom he gave two things. He taught them from the knowledge he had gained by his comprehensive reading. More importantly, Maurice instilled in students "the habit of inquiry and research" and a "desire for knowledge and the process of independent thought."[51]

Written legacyMaurice's written legacy includes "nearly 40 volumes", and they hold "a permanent place in the history of thought in his time."[39] His writings are "recognizable as the utterance of a mind profoundly Christian in all its convictions."[80]

By themselves, two of Maurice's books, The Kingdom of Christ (1838 and later editions) and Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (2 volumes, 1871–1872), are "remarkable enough to have made their writer famous." But there more reasons for Maurice's fame. In his "life-work" Maurice was "constantly teaching, writing, guiding, organizing; training up others to do the same kind of work, but giving them something of his spirit, never simply his views." He drew out "all the best that was in others, never trying to force himself upon them." With his opponents, Maurice tried to find some "common ground" between them. None who knew him personally "could doubt that he was indeed a man of God."[81]

In The Kingdom of Christ Maurice viewed the true church as a united body that transcended the "diversities and partialities of its individual members, factions, and sects". The true church had six signs: "baptism, creeds, set forms of worship, the eucharist, an ordained ministry, and the Bible." Maurice's ideas were reflected a half-century later by William Reed Huntington and the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral.[74] The modern ecumenical movement also incorporated Maurice's ideas contained in his The Kingdom of Christ.[39]

Decline and revival of interest in legacyInterest in the vast legacy of writings bequeathed by Maurice declined even before his death. Hugh Walker, a fellow academic, predicted in 1910 that neither of Maurice's major works, his Theological Essays (1853) and his Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (1871–1872), will "stand the test of time."[82] However, "this phase of neglect has passed."[80]

"Since World War II there has been a revival of interest in Maurice as a theologian."[74] During this period, twenty-three (some only in part) books about Maurice have been published as can be seen in the References section of this article.

Maurice is honoured with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer on 1 April as "Frederick Denison Maurice, Priest, 1872" and a brief biography is included in the church's Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints.[83]

Despite Maurice's dismissal by King's College after the publication of his Theological Essays, "a chair at King's, the F D Maurice Professorship of Moral and Social Theology, now commemorates his contribution to scholarship at the College."[84]

King's College also established "The FD Maurice Lectures" in 1933 in honour of Maurice. Maurice, who was Professor of English Literature and History (1840–1846) and then Professor of Theology (1846–1853)."[85]

WritingsMaurice's writings result from diligent work on his part. As a rule he "rose early" and did his socializing with friends at breakfast. He dictated his writings until dinner-time. The manuscripts he dictated were "elaborately corrected and rewritten" before publication.[58]

Maurice's writings hold "a permanent place in the history of thought in his time."[39] Some of the following were "rewritten and in a measure recast, and the date given is not necessarily that of the first appearance." Most of these writings "were first delivered as sermons or lectures."[51]

• Eustace Conway, or the Brother and Sister], a novel in three volumes (1834): Volume 1no online, Volume 2, and Volume 3

• Subscription no Bondage, Or The Practical Advantages Afforded by the Thirty-nine Articles as Guides in All the Branches of Academical Education under the pseudonym Rusticus (1835)

• The Kingdom of Christ, or Hints to a Quaker, respecting the principles, constitution and ordinances of the Catholic Church (1838)Volume 1 Volume 2

• Has the Church or the State power to Educate the Nation?[permanent dead link] (1839)

• Reasons for Not Joining a Party in the Church; a Letter to S Wilberforce (1841)

• Three Letters to the Rev W Palmer on the Jerusalem Bishopric (1842)

• Right and Wrong Methods of Supporting Protestantism: A Letter to Lord Ashley (1843)

• Christmas Day and Other Sermons (1843)

• The New Statute and Dr Ward: A Letter to a Non-resident Member of Convocation (1845)

• Thoughts on the Rule of Conscientious Subscription (1845)

• The Epistle to the Hebrews (1846)

• The Religions of the World and Their Relation to Christianity (1847)

• Letter on the Attempt to Defeat the Nomination of Dr Hampden (1847)

• Thoughts on the Duty of a Protestant on the Present Oxford Election (1847)

• The Lord's Prayer: Nine Sermons (1848)

• "Queen's College, London: its Objects and Methods" in Queen's College, London: its Objects and Methods (1848)

• Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy (at first an article in the Encyclopædia Metropolitana, 1848) Volume 1 Ancient Philosophy Volume 2 The Christian Fathers Volume 3 Mediaeval Philosophy Volume 4 Modern Philosophy

• The Prayer Book, Considered Especially in Reference to the Romish System (1849)

• The Church a Family (1850)

• Queen's College, London in reply to the Quarterly Review (1850)

• The Old Testament: Nineteen Sermons on the First Lessons for the Sundays from Septuagesima (1851)

• Sermons on the Sabbath Day, on the Character of the Warrior, and on the Interpretation of History (1853)

• The Word Eternal and the Punishment of the Wicked: A Letter to Dr Jelf (1853)

• Theological Essays (1853)

• The Prophets and Kings of the Old Testament: a series of sermons (1853)

• The Unity of the New Testament: A Synopsis of the First Three Gospels and of the Epistles of St. James, St. Jude, St. Peter, and St. Paul in two volumes (1854)

Volume 1 Volume 2

The Unity of the New Testament, 1st American ed in one volume (1879)

Extensive review of The Unity of the New Testament in The Unitarian Review (June 1876), 581–594.

• Lectures on the Ecclesiastical History of the First and Second Centuries (1854)

• The Doctrine of Sacrifice Deduced From the Scriptures (1854)

• The Unity of the New Testament, a Synopsis of the First Three Gospels, and the Epistles of St James, St Jude, St Peter, and St Paul in two volumes(1854)

• The Unity of the New Testament, 1st American ed in one volume (1879)

• Learning and Working: six lectures and The Religion of Rome: 4 lectures (1855)

• The Patriarchs and Lawgivers of the Old Testament: a series of sermons (1855)

• The Gospel of St John: a series of discourses (1857)

• The Epistles of St John: a series of lectures on Christian ethics (1857)

• The Eucharist: five sermons (1857)

• The Indian Crisis: five sermons (1857)

• What is Revelation?: a Series of Sermons on the Epiphany (1859)

• Sequel to the Enquiry, What is Revelation? (1860)

• Address of Congratulation to the Rev. F. D. Maurice, on His Nomination to St. Peter's, Vere Street; with His Reply Thereto (1860)

• Lectures on the Apocalypse, or the Book of Revelation of St John the Divine (1861)

• Dialogues Between a Clergyman and a Layman on Family Worship (1862)

• Claims of the Bible and of Science : Correspondence Between a Layman and the Rev. F. D. Mauhice on Some Questions Arising out of the Controversy Respecting the Pentateuch (1863)

• The Conflict of Good and Evil in our Day: twelve letters to a missionary (1864)

• The Gospel of the Kingdom of Heaven: a course of lectures on the Gospel of St Luke (1864)

• The Commandments Considered as Instruments of National Reformation (1866)

• Casuistry, Moral Philosophy, and Moral Theology: inaugural lecture at Cambridge (1866)

• The Working Men’s College (1866)

• The Ground and Object of Hope for Mankind: four university sermons (1867)

• The Workman and the Franchise: Chapters from English History on the Representation and Education of the People (1866)

• The Conscience: Lectures on Casuistry (1868)

• Social Morality: twenty-one lectures delivered in the University of Cambridge (1869)

• The Lord's Prayer, a Manual (1870).

• The Friendship of Books and Other Lectures, ed. T. Hughes (1873)

• Sermons Peached in Country Churches (1873)

• Faith and Action from the Writings of F.D. Maurice (1886)

• The Acts of the Apostles: A Course of Sermons (1894) Preached at St Peter, Vere Street.

See also• Frederick Barton Maurice

References

Notes1. Collins 1902, pp. 343–344; McIntosh 2018, pp. 14–15; Morris 2005, pp. 34–43; Young 1992, pp. 118–119.

2. Young 1992, pp. 118–119.

3. Collins 1902, p. 344; Ramsey 1951, p. 22.

4. Cadwell 2013, p. 156.

5. Avis 2002, pp. 290–293.

6. Christensen 1973, p. 64; Young 1992, p. 7.

7. Scotland 2007, p. 140.

8. Kilcrease 2011, p. 2; Knight 2016, p. 186.

9. Young 1984, p. 332.

10. Chorley, E. Clowes (1946). Men and Movements in the American Episcopal Church. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 289. Cited in Harp 2003, p. 195.

11. Goroncy 2013, p. 83.

12. Cohen 2013.

13. Geddes Poole 2014, pp. 31, 257.

14. Geddes Poole 2014, pp. 106, 170, 257.

15. McIntosh 2018, p. 15.

16. Knight 2016, p. 127.

17. Farrar 1995, p. 171.

18. Chapman 2007, p. 81; Kilcrease 2011, pp. 2, 8; Knight 2016, p. 127; Young 1992, pp. 183–184.

19. White 1999, p. 28.

20. Geddes Poole 2014, pp. 106, 257; Morris 2017, p. 14.

21. Young 1992, pp. 183–184.

22. Patrick 2015, p. 15.

23. Chapman 2012, p. 186.

24. Avis, Paul (1989). "The Atonement". In Wainwright, Geoffrey (ed.). Keeping the Faith: Essays to Mark the Centenary of Lux Mundi. London. p. 137. Cited in Young 1992, p. 7.

25. Palgrave 1896, p. 507.

26. Wilson, A. N. (16 April 2001). "Why Maurice Is an Inspiration to Us All". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

27. Young 1984, p. 332; Young 1992, p. 7.

28. Annan 1987, p. 8.

29. Stockitt 2011, p. 177.

30. Cooper 1981, p. 206.

31. Chapman 2007, p. 81; Young 1992, pp. 183–184.

32. Wright 1907, p. 167.

33. Cadwell 2013, p. 33; Young 1984, p. 332.

34. Hinson-Hasty 2006, p. 101.

35. Schultz 2015.

36. Young 1984, p. 332; Young 1992, pp. 183–184.

37. Crook, Paul (2013). "Alec Vidler: On Christian Faith and Secular Despair" (PDF). Paul Crook. p. 2. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

38. Scotland 2007, p. 204.

39. "Frederick Denison Maurice." Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Academic. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Accessed 3 Jan. 2016.

40. Reardon 2006.

41. Maurice 1884a, p. 175.

42. Collins 1902.

43. Collins 1902, pp. 330–331.

44. "MAURICE, Professor Frederick Denison (1805–1872)", Collections, London: King's College.

45. Morris 2005, p. 34–36.

46. Masterman 1907, p. 16.

47. Crockford's Clerical Directory 1868, pp. 448–449; Morley 1877, p. 421.

48. Masterman 1907, p. 19.

49. Crockford's Clerical Directory 1868, pp. 448–449.

50. A. Gardner, The Scottish Review, Volume 3 (1884), 349. Online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=msgZm ... navlinks_s.

51. Chisholm 1911.

52. A. Gardner, The Scottish Review, Volume 3 (1884), 351. Online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=msgZm ... navlinks_s.

53. "Croudace, Camilla Mary Julia (1844–1926), supporter of education for women | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography".

http://www.oxforddnb.com. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52267. Retrieved 6 December2019.

54. John William Adamson, English Education, 1789–1902(Cambridge University, 1930/1964), 283.

55. Bingham 2004.

56. Episcopal Church 2010, p. 300.

57. A. Gardner, The Scottish Review, Volume 3 (1884), 351–353. Online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=msgZm ... navlinks_s.

58. Stephen 1894.

59. A. Gardner, The Scottish Review, Volume 3 (1884), 355. Online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=msgZm ... navlinks_s.

60. "About St Edward's". Cambridge, England: St Edward King and Martyr. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

61. The London Quarterly Review, Volume 62" (1884), 347.

62. Waldron 2007, p. 15.

63. Close 1872, pp. 47–48.

64. Lowder 1888, p. 138.

65. J S Mill, Autobiography (Penguin 1989) p. 124

66. Walker 1910, p. 100.

67. Jabberwocky, Volumes 19–21 (Lewis Carroll Society, 1990), 4.

68. Grant Duff 1897, p. 78.

69. Short 2011, p. 418.

70. Gorton 1879, p. 203.

71. Orens 2003, p. 11.

72. Hughes, Thomas (1904). Preface. The friendship of books, and other lectures. By Maurice, Frederick Denison (4th ed.). London and New York: Macmillan. p. vi. OL 7249916M. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

73. The Co-operative Wholesale Society’s Annual, Almanack, and Diary for the Year 1883: Containing an Account of the Statistics of the Society from Its Commencement in 1864, etc., Volume 1883 (Co-operative Wholesale Society [and] Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society, 1883), 174–180, 181.

74. Armentrout & Slocum 2000.

75. Maurice 1884b, p. 137.

76. The New Monthly Magazine, Volume 140 (Chapman and Hall, 1867), 333–334.

77. "Appendix to the Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Royal Commission on Labour, One Volume" in Sessional papers. Inventory control record 1, Vol 39 including the "Fourth Report of the Royal Commission on Labour" (Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, 1894), Appendix XXIII, "Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations, Established 1850, London," 54.

78. Sessional papers. Inventory control record 1, Vol 39including the "Fourth Report of the Royal Commission on Labour" (Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons, 1894), 62.

79. The London Quarterly Review, Volume 62 (T. Woolmer, 1884), 348. Online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=j9E5A ... navlinks_s.

80. Reardon 1980, p. 158.

81. Collins 1902, pp. 333, 358–359.

82. Walker 1910, p. 101.

83. Episcopal Church 2010, pp. 10, 300.

84. "Frederick Maurice". King's College London. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

85. "The FD Maurice Lectures". King's College London. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

BibliographyAnnan, Noel (1987). "Richard Llewelyn-Davies and the Architect's Dilemma" (PDF). Princeton, New Jersey: Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

Armentrout, Don S.; Slocum, Robert Boak, eds. (2000). "Maurice, Frederick Denison (Aug. 29, 1805–Apr. 1, 1872)". An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church. New York: Church Publishing. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-89869-701-8.

Avis, Paul (2002). Anglicanism and the Christian Church: Theological Resources in Historical Perspective (rev. ed.). Edinburgh: T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08849-9.

Bingham, Caroline (2004). "Bishop, Matilda Ellen". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/48431.

Cadwell, Matthew Peter (2013). In Search of Anglican Comprehensiveness: A Study in the Theologies of Hooker, Maurice, and Gore(PhD thesis). Toronto: University of Toronto. hdl:1807/43415.

Chapman, Mark D. (2007). "Catholic Openness and the Nature of Christian Politics". In Chapman, Mark D. (ed.). Living the Magnificat: Affirming Catholicism in a Broken World. London: Mowbray. pp. 71–87. ISBN 978-1-4411-6500-8.

——— (2012). Anglican Theology. London: A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-25031-5.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Maurice, John Frederick Denison". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 910.

Christensen, Torben (1973). The Divine Order: A Study in F. D. Maurice's Theology. Acta Theologica Danica. 11. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-03693-2.

Close, Francis (1872). An Examination of the Witnesses, and Their Evidence, Given Before a Royal Commission Upon the Administration and Operation of the "Contagious Diseases Acts, 1871". London: Tweedie & Co. Retrieved 28 September2017.

Cohen, Morton N. (2013). "Dodgson, Charles Lutwidge [pseud. Lewis Carroll] (1832–1898)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7749.

Collins, William Edward (1902). "Frederick Denison Maurice". In Collins, William Edward (ed.). Typical English Churchmen: From Parker to Maurice. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. pp. 327–260. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Cooper, Francis Marion (1981). The Background and Development of "Evangelical Catholicism" and Its Expression in the Ministry of William Augustus Muhlenberg (PhD thesis). St Andrews, Scotland: University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7113.

Crockford's Clerical Directory. London: Horace Cox. 1868. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Episcopal Church (2010). Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints (PDF). New York: Church Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89869-678-3. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Farrar, F. W. (1995) [1979]. "Schools and Universities on the Continent". In Dawson, Carl; Pfordresher, John (eds.). Matthew Arnold. Volume 1: Prose Writings. London: Routledge (published 2013). pp. 171–174. doi:10.4324/9781315004617. ISBN 978-1-136-17500-8.

Geddes Poole, Andrea (2014). Philanthropy and the Construction of Victorian Women's Citizenship: Lady Frederick Cavendish and Miss Emma Cons. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-4231-7.

Goroncy, Jason (2013). Hallowed Be Thy Name: The Sanctification of All in the Soteriology of P. T. Forsyth. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark. doi:10.5040/9781472551207. ISBN 978-0-567-40253-0.

Gorton, David A., ed. (1879). "Review of The Unity of the New Testament by Frederick Denison Maurice". The National Quarterly Review. 38 (75): 202–203. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Grant Duff, Mountstuart P. (1897). Notes from a Diary, 1851–1872. 1. London: John Murray. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Harp, Gillis J. (2003). Brahmin Prophet: Phillips Brooks and the Path of Liberal Protestantism. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8476-9961-2.

Hinson-Hasty, Elizabeth L. (2006). Beyond the Social Maze: Exploring Vida Dutton Scudder's Theological Ethics. New York: T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-51593-3.

Kilcrease, Bethany (2011). "'The Mass and the Masses': Nineteenth-Century Anglo-Catholic Socialism". Conference of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

Knight, Frances (2016). Victorian Christianity at the Fin de Siècle: The Culture of English Religion in a Decadent Age. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85772-789-3.

Lowder, Charles, ed. (1888). Richard Chenevix Trench, Archbishop: Letters and Memorials. 1. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Masterman, C. F. G. (1907). Frederick Denison Maurice. Leaders of the Church, 1800–1900. London: A. R. Mowbray & Co. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Maurice, Frederick Denison (1884a). Maurice, Frederick (ed.). The Life of Frederick Denison Maurice: Chiefly Told in His Own Letters. 1. London: Macmillan and Co. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

——— (1884b). Maurice, Frederick (ed.). The Life of Frederick Denison Maurice: Chiefly Told in His Own Letters. 2. London: Macmillan and Co. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

McIntosh, John A. (2018). Anglican Evangelicalism in Sydney, 1897 to 1953: Nathaniel Jones, D. J. Davies and T. C. Hammond. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-4307-1.

Morley, Henry (1877). Illustrations of English Religion. London: Cassell & Company. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Morris, Jeremy (2005). F. D. Maurice and the Crisis of Christian Authority. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926316-5.

——— (2017). "F. D. Maurice and the Myth of Christian Socialist Origins". In Spencer, Stephen (ed.). Theology Reforming Society: Revisiting Anglican Social Theology. London: SCM Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-334-05373-6.

Orens, John Richard (2003). Stewart Headlam's Radical Anglicanism: The Mass, the Masses, and the Music Hall. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02824-3.

Palgrave, R. H. Inglis, ed. (1896). "Kingsley, Charles (1819–1875)". Dictionary of Political Economy. 2. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 507–508. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-10358-4. ISBN 978-1-349-10360-7.

Patrick, Graham A. (2015). F. J. A. Hart: Eminent Victorian. London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781474266611. ISBN 978-1-4742-3165-7.

Ramsey, Arthur Michael (1951). F. D. Maurice and the Conflicts of Modern Theology. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press (published 2014). ISBN 978-1-107-66891-1.

Reardon, Bernard M. G. (1980). Religious Thought in the Victorian Age. London: Longman Group.

——— (2006) [2004]. "Maurice, (John) Frederick Denison". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18384.

Schultz, Barton (2015). "Henry Sidgwick". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, California: Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

Scotland, Nigel (2007). Squires in the Slums: Settlements and Missions in Late Victorian Britain. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-336-0.

Short, Edward (2011). Newman and His Contemporaries. London: T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-10648-3.

Stephen, Leslie (1894). "Maurice, Frederick Denison". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 37. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 97–105.

Stockitt, Robin (2011). Imagination and the Playfulness of God: The Theological Implications of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Definition of the Human Imagination. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-61097-347-2.

Waldron, Jeremy (2007). "Mill on Liberty and on the Contagious Diseases Acts". In Urbinati, Nadia; Zakaras, Alex (eds.). J.S. Mill's Political Thought: A Bicentennial Reassessment. Cambridge, England: Cambridge, University Press. pp. 11–42. ISBN 978-0-511-27395-7.

Walker, Hugh (1910). The Literature of the Victorian Era. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 28 September2017.

White, James F. (1999). The Sacraments in Protestant Practice and Faith. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-03402-4.

Wright, Thomas (1907). The Life of Walter Pater. 1. London: Everett & Co. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

Young, David (1984). "F.D. Maurice and the Unitarians" (PDF). Churchman. 98 (4): 332–340. ISSN 0009-661X. Retrieved 21 May2019.

——— (1992). F. D. Maurice and Unitarianism. Oxford: Clarendon Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198263395.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-826339-5. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

Further readingBrose, Olive J. (1971). Frederick Denison Maurice: Rebellious Conformist. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Davies, Walter Merlin (1964). An Introduction to F. D. Maurice's Theology.

Higham, Florence May Greir Evans (1947). Frederick Denison Maurice.

Loring Conant, David (1989). F. D. Maurice's Vision of Church and State (AB thesis). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University.

McClain, F. M. (1972). F. D. Maurice: Man and Moralist.

McClain, Frank; Norris, Richard; Orens, John (1982). F. D. Maurice: A Study.

——— (2007). To Build Christ's Kingdom: An F. D. Maurice Reader.

Norman, E. R. (1987). The Victorian Christian Socialists.

Ranson, Guy Harvey (1956). F. D. Maurice's Theology of Society: A Critical Study (PhD thesis). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University.

Reckitt, Maurice Benington (1947). Maurice to Temple: A Century of the Social Movement in the Church of England.

Rogerson, John W. (1997). Bible and Criticism in Victorian Britain: Profiles of F.D. Maurice and William Robertson Smith.

Schmidt, Richard H. (2002). Glorious Companions: Five Centuries of Anglican Spirituality.

Schroeder, Steven (1999). The Metaphysics of Cooperation: A Study of F. D. Maurice.

Tulloch, John (1888). "Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley". Movements of Religious Thought in Britain during the Nineteenth Century. London: Longmans, Green, & Co. pp. 254–294. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Vidler, Alec (1948a). The Theology of F. D. Maurice.

——— (1948b). Witness to the Light: F. D. Maurice's Message for Today.

——— (1966). F. D. Maurice and Company.

Wood, H. G. (1950). Frederick Denison Maurice.

External links• Works by Frederick Denison Maurice at Project Gutenberg

• "Frederick Denison Maurice"

• "MAURICE, Professor Frederick Denison (1805–1872)"

• Works by or about Frederick Denison Maurice at Internet Archive

/ 1887 / -- / --

/ 1887 / -- / -- / 1880/1907 / -- / --

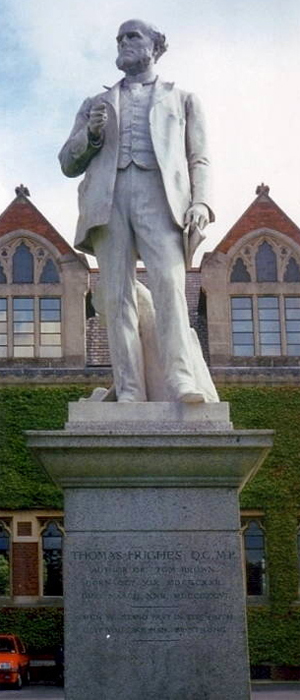

/ 1880/1907 / -- / -- / 1882 / -- / Author Thomas Hughes (1822–1896)

/ 1882 / -- / Author Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) / 1884 / Thomas Hughes / Community in Hughes's native Berkshire, England

/ 1884 / Thomas Hughes / Community in Hughes's native Berkshire, England / 1884/1970s / Sir Henry Kimber (1834–1923) / Kimber's son

/ 1884/1970s / Sir Henry Kimber (1834–1923) / Kimber's son / 1886 / Montgomery Boyle / Roslyn Castle in Scotland

/ 1886 / Montgomery Boyle / Roslyn Castle in Scotland / 1881/2007 / Robert Walton /

/ 1881/2007 / Robert Walton /

/ 1880s/1985 / -- / Harrow Road in London

/ 1880s/1985 / -- / Harrow Road in London / 1880s / Abner Ross / Originally located at Deer Lodge, a nearby resort founded by Ross in the 1880s

/ 1880s / Abner Ross / Originally located at Deer Lodge, a nearby resort founded by Ross in the 1880s / 1880/1970s / -- / --

/ 1880/1970s / -- / -- / 1880/1970s / Publicly owned / --

/ 1880/1970s / Publicly owned / -- / 1884 / Russell Sturgis / --

/ 1884 / Russell Sturgis / -- / 1881 / Frederick Wellman / Adena Mansion in Ohio, built for Wellman's grandfather-in-law

/ 1881 / Frederick Wellman / Adena Mansion in Ohio, built for Wellman's grandfather-in-law / 1887 / Frederick Wellman / --

/ 1887 / Frederick Wellman / -- / 1880 / Nathan Tucker / Linden trees planted around the house

/ 1880 / Nathan Tucker / Linden trees planted around the house / 1880 / Ross Brown / --

/ 1880 / Ross Brown / -- / 1880s/2007 / -- / Rugby architect/builder Cornelius Onderdonk

/ 1880s/2007 / -- / Rugby architect/builder Cornelius Onderdonk / 1880 / -- / --

/ 1880 / -- / -- / 1880s/1960s / -- / --

/ 1880s/1960s / -- / -- / 1881 / T. Lyon White / --

/ 1881 / T. Lyon White / -- / 1881 / Margaret Hughes / Uffington, England

/ 1881 / Margaret Hughes / Uffington, England / 1884 / Daniel Ellerby / --

/ 1884 / Daniel Ellerby / -- / 1884 / Beriah Riddell / --

/ 1884 / Beriah Riddell / --