by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/5/20

Carnegie Corporation of New York

The Corporation's headquarters at 437 Madison Avenue in New York

Formation: 9 June 1911; 108 years ago

Founder: Andrew Carnegie

Type: Foundation

Legal status: Nonprofit organization

Purpose: To promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding

Headquarters: New York, United States

Region: Global

Methods: Grant-giving

Fields: Education, democracy, international peace, higher education in Africa

President: Vartan Gregorian

Chair of the Board: Thomas Kean

Revenue (2018): $253 million[1]

Expenses (2018): $180 million[1]

Endowment (2018): $3.5 billion[1]

Website http://www.carnegie.org

The Carnegie Corporation of New York MHL is a philanthropic fund established by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to support education programs across the United States, and later the world.[2] Carnegie Corporation has endowed or otherwise helped to establish institutions that include the United States National Research Council, what was then the Russian Research Center at Harvard University (now known as the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies),[3] the Carnegie libraries and the Children's Television Workshop. It also for many years generously funded Carnegie's other philanthropic organizations, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP), the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (CFAT), and the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS).

History

Founding and early years

By 1911 Andrew Carnegie had endowed five organizations in the US and three in the United Kingdom, and given more than $43 million to build public libraries and given another almost $110 million elsewhere. But ten years after he sold the Carnegie Steel Company, more than $150 million remained in his accounts and at 76, he wearied of philanthropic choices. Long-time friend Elihu Root suggested he establish a trust. Carnegie transferred most of his remaining fortune into it, and made the trust responsible for distributing his wealth after he died. Carnegie's previous charitable giving had used conventional organizational structures, but he chose a corporation as the structure for his last and largest trust. Chartered by the State of New York as the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the corporation's capital fund, originally worth about $135 million, had a market value of $1.55 billion on March 31, 1999.

In 1911-1912, Carnegie gave the corporation $125 million. At that time the corporation was the largest single philanthropic charitable trust ever established. He also made it a residual legatee under his will so it therefore received an additional $10 million, the remainder of his estate after had paid his other bequests. Carnegie reserved a portion of the corporation's assets for philanthropy in Canada and the then-British Colonies, an allocation first referred to as the Special Fund, then the British Dominions and Colonies Fund, and later the Commonwealth Program. Charter amendments have allowed the corporation to use 7.4 percent of its income in countries that are or once were members of the British Commonwealth.[clarification needed]

In its early years Carnegie served as both president and trustee. His private secretary James Bertram and his financial agent, Robert A. Franks, acted as trustees as well and, respectively, corporation secretary and treasurer. This first executive committee made most of the funding decisions. Other seats on the board were held ex officio by presidents of five previously-established US Carnegie organizations:

• Carnegie Institute (of Pittsburgh) (1896),

• Carnegie Institution of Washington (1902),

• Carnegie Hero Fund Commission (1904),

• Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (CFAT) (1905),

• Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) (1910).

After Carnegie died in 1919, the trustees elected a full-time salaried president as the trust's chief executive officer and ex officio trustee. For a time the corporation's gifts followed the patterns Carnegie had already established. Grants for public libraries and church organs continued until 1917, and also went to other Carnegie organizations, and universities, colleges, schools, and educational agencies. Carnegie's letter of gift to the original trustees making the endowment said that the trustees would "best conform to my wishes by using their own judgement."[4] Corporation strategies changed over the years but remained focused on education, although the trust did also increasingly fund scientific research, convinced that the nation needed more scientific expertise and "scientific management". It also worked to build research facilities for the natural and social sciences. The corporation made large grants to the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the National Bureau of Economic Research, Stanford University's now-defunct Food Research Institute[5] and the Brookings Institution, then became interested in adult education and lifelong learning, an obvious follow-on to Carnegie's vision for libraries as "the university of the people". In 1919 it initiated the Americanization Study to explore educational opportunities for adults, primarily for new immigrants.

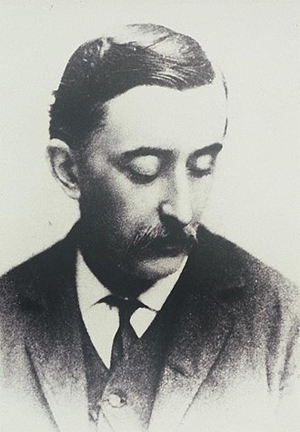

Frederick P. Keppel

With Frederick P. Keppel as president (1923-1941), the Carnegie Corporation shifted from creating public libraries to strengthening library infrastructure and services, developing adult education, and adding arts education to the programs of colleges and universities. The foundation's grants in this period have a certain eclectic quality and remarkable perseverance in its chosen causes.[6]

Keppel initiated a famous 1944 study of race relations in the United States by the Swedish social economist Gunnar Myrdal in 1937 by naming a non-American outsider as manager of the study. His theory that this task should be done by someone unencumbered by traditional attitudes or earlier conclusions led to Myrdal's widely heralded book American Dilemma (1944). The book had no immediate effect on public policy, but was later much cited in legal challenges to segregation. Keppel believed foundations should make facts available and let them facts speak for themselves. His cogent writings on philanthropy made a lasting impression on field and influenced the organization and leadership of many new foundations.[7]

In 1927 Keppel toured sub-Saharan Africa and recommended a first set of grants to establish public schools in eastern and southern Africa. Other grants went to for municipal library development in South Africa. During 1928 the corporation initiated the Carnegie Commission on the Poor White Problem in South Africa. Better known as the "Carnegie Poor White Study", it promoted strategies to improve the lives of rural Afrikaner whites and other poor whites in general. A memorandum sent to Keppel said there was "little doubt that if the natives were given full economic opportunity, the more competent among them would soon outstrip the less competent whites"[8] Keppel endorsed the project that produced the report, motivated by his concern with maintaining existing racial boundaries.[8] The corporation's concern for the so-called "poor white problem" in South Africa stemmed at least in part from similar misgivings about poor whites in the American South.[8]

White poverty defied traditional understandings of white racial superiority and thus became the subject of study. The report recommended that "employment sanctuaries" be established for poor white workers and that poor white workers replace "native" workers in most skilled aspects of the economy.[9] The authors of the report suggested that white racial deterioration and miscegenation would be the outcome[8] unless something was done to help poor whites, endorsing the necessity of the role of social institutions to play in the successful maintenance of white racial superiority.[9][10] The report expressed trepidation concerning the loss of white racial pride, with the implicit consequence that poor whites would not successfully resist "Africanisation."[8] The report sought, in part, to forestall the historically inevitable accession of a communal, class based, democratic socialist movement aimed at uniting the poor of each race in common cause and brotherhood.[11]

Charles Dollard

World War II and its immediate aftermath were a relatively inactive period for the Carnegie Corporation. Charles Dollard had joined the staff in 1939 as Keppel's assistant and became president in 1948. The foundation took greater interest in the social sciences, and particularly the study of human behavior. The trust also entered into international affairs. Dollard urged it to fund quantitative, "objective" social science research like research in physical sciences, and help to diffuse the results through major universities. The corporation advocated for standardized testing in schools to determine academic merit regardless of the student's socio-economic background. Its initiatives have also included helping to broker the creation of the Educational Testing Service in 1947.

The corporation determined that the US increasingly needed policy and scholarly expertise in international affairs, and so tied into area studies programs at colleges and universities as well as the Ford Foundation. In 1948 the trust also provided the seed money to establish the Russian Research Center at Harvard University, today known as the Davis Center for Russia and Eurasian Studies,[12] as an organization that could address large-scale research from both a policy and educational points of view.

In 1951 the Group Areas Act took effect in South Africa and effectively put the apartheid system into place, leading to political ascendancy for Afrikaners and dispossession for many Africans and colored people suddenly required to live in certain areas of the country only, on pain of imprisonment for remaining in possession of homes in areas designated for whites. The Carnegie corporation pulled its philanthropic endeavors from South Africa for more than two decades after this political change, turning its attention from South Africa to developing East African and West African universities instead.

John Gardner

John W. Gardner was promoted from a staff position to the presidency in 1955. Gardner simultaneously became president of the CFAT, which was housed at the corporation. During Gardner's time in office the Carnegie Corporation worked to upgrade academic competence in foreign area studies and strengthened its liberal arts education program. In the early 1960s it inaugurated a continuing education program and funded development of new models for advanced and professional study by mature women. Important funding went to the key early experiments in continuing education for women, with major grants to the University of Minnesota (1960, co-directors Elizabeth L. Cless and Virginia L. Senders), Radcliffe College (1961, under President Mary Bunting), and Sarah Lawrence College (1962, under Professor Esther Raushenbush).[13] Gardner's interest in leadership development led to the White House Fellows program in 1964.

Notable grant projects in higher education in sub-Saharan Africa include the 1959-60 Ashby Commission study of Nigerian needs in postsecondary education. This study stimulated aid increases from the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States to African nations' systems of higher and professional education. Gardner had a strong interest in education, but as a psychologist he believed in the behavioral sciences and urged the corporation to funded much of the US' basic research on cognition, creativity, and the learning process, particularly among young children, associating psychology and education. Perhaps its most important contribution to reform of pre-college education at this time was the series of education studies done by James B. Conant, former president of Harvard University; in particular, Conant's study of comprehensive American high schools (1959) resolved public controversy concerning the purpose of public secondary education, and made the case that schools could adequately educate both average students and the academically gifted.

Under Gardner, the corporation embraced strategic philanthropy—planned, organized, and deliberately constructed to attain stated ends. Funding criteria no longer required just a socially desirable project. The corporation sought out projects that would produce knowledge leading to useful results, communicated to decision-makers, the public, and the media, in order to foster policy debate. Developing programs that larger organizations, especially governments, could implement and scale in size became a major objective. The policy shift to institutional knowledge transfer came in part as a response to relatively diminished resources that made it necessary to leverage assets and "multiplier effects" to have any effect at all. The corporation considered itself a trendsetter in philanthropy, often funding research or providing seed money for ideas while others financed more costly operations. For example, ideas it advanced resulted in the National Assessment of Educational Progress, later adopted by the federal government. A foundation's most precious asset was its sense of direction, Gardner said,[14] gathering a competent professional staff of generalists that he called his "cabinet of strategy," and regarded as a resource as important to the corporation as its endowment.

Alan Pifer

While Gardner's opinion of educational equality was to multiply the channels through which an individual could pursue opportunity, it was during the term of long-time staff member Alan Pifer, who became acting president during 1965 and president during 1967 (again of both Carnegie Corporation and the CFAT), that the foundation began to respond to claims by various groups, including women, for increased power and wealth. The corporation developed three interlocking objectives: prevention of educational disadvantage; equality of educational opportunity in the schools; and broadened opportunities in higher education. A fourth objective cutting across these programs was to improve the democratic performance of government. Grants were made to reform state government as the laboratories of democracy, underwrite voter education drives, and mobilize youth to vote, among other measures. Use of the legal system became a method for achieving equal opportunity in education, as well as redress of grievance, and the corporation joined the Ford and Rockefeller foundations and others in funding educational litigation by civil rights organizations. It also initiated a multifaceted program to train black lawyers in the South for the practice of public interest law and to increase the legal representation of black people.

Maintaining its commitment to early childhood education, the corporation endorsed the application of research knowledge in experimental and demonstration programs, which subsequently provided strong evidence of the long-term positive effects of high-quality early education, particularly for the disadvantaged. A 1980 report on an influential study, the Perry Preschool Project of the HighScope Educational Research Foundation, on the outcomes for sixteen-year-olds enrolled in the experimental preschool programs provided crucial evidence that safeguarded Project Head Start in a time of deep cuts to federal social programs. The foundation also promoted educational children's television and initiated the Children's Television Workshop, producer of Sesame Street and other noted children's programs. Growing belief in the power of educational television prompted creation of the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, whose recommendations were adopted into the Public Broadcasting Act of 1968 that established a public broadcasting system. Many other reports on US education the corporation financed at this time, included Charles E. Silberman's acclaimed Crisis in the Classroom (1971), and the controversial Inequality: A Reassessment of the Effect of Family and Schooling in America by Christopher Jencks (1973). This report confirmed quantitative research, e.g. the Coleman Report, showed that in public schools resources only weakly correlated with educational outcomes, which coincided with the foundation's burgeoning interest in improved school effectiveness.

Becoming involved with South Africa again during the mid-1970s, the corporation worked through universities to increase the legal representation of black people and increase the practice of public interest law. At the University of Cape Town, it established the Second Carnegie Inquiry into Poverty and Development in Southern Africa, this time to examine the legacies of apartheid and make recommendations to nongovernmental organizations for actions commensurate with the long-run goal of achieving a democratic, interracial society.

The influx of nontraditional students and "baby boomers" into higher education prompted formation of the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education (1967), funded by the CFAT. (During 1972, the CFAT became an independent institution after experiencing three decades of restricted control over its own affairs.) In its more than ninety reports, the commission made detailed suggestions for introducing more flexibility into the structure and financing of higher education. One outgrowth of the commission's work was creation of the federal Pell grants program offering tuition assistance for needy college students. The corporation promoted the Doctor of Arts "teaching" degree as well as various off-campus undergraduate degree programs, including the Regents Degree of the State of New York and Empire State College. The foundation's combined interest in testing and higher education resulted in establishment of a national system of college credit by examination (College-Level Entrance Examination Program of the College Entrance Examination Board). Building on its past programs to promote the continuing education of women, the foundation made a series of grants for the advancement of women in academic life. Two other study groups formed to examine critical problems in American life were the Carnegie Council on Children (1972) and the Carnegie Commission on the Future of Public Broadcasting (1977), the latter formed almost ten years after the first commission.

David A. Hamburg

David A. Hamburg, a physician, educator, and scientist with a public health background, became president in 1982 intending to mobilize the best scientific and scholarly talent and thinking on "prevention of rotten outcomes" - from early childhood to international relations. The corporation pivoted from higher education to the education and healthy development of children and adolescents, and the preparation of youth for a scientific and technological, knowledge-driven world. In 1984 the corporation established the Carnegie Commission on Education and the Economy. Its major publication, A Nation Prepared (1986), reaffirmed the role of the teacher as the "best hope" for quality in elementary and secondary education. That report led to the establishment a year later of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, to consider ways to attract able candidates to teaching and recognize and retain them. At the corporation's initiative, the American Association for the Advancement of Science issued two reports, Science for All Americans (1989) and Benchmarks for Science Literacy (1993), which recommended a common core of learning in science, mathematics, and technology for all citizens and helped set national standards of achievement.

A new emphasis for the corporation was the danger to world peace posed by the superpower confrontation and weapons of mass destruction. The foundation underwrote scientific study of the feasibility of the proposed federal Strategic Defense Initiative and joined the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation to support the analytic work of a new generation of arms control and nuclear nonproliferation experts. After the end of the USSR, corporation grants helped promote the concept of cooperative security among erstwhile adversaries and projects to build democratic institutions in the former Soviet Union and Central Europe. The Prevention of Proliferation Task Force, coordinated by a grant to the Brookings Institution, inspired the Nunn-Lugar Amendment to the Soviet Threat Reduction Act of 1991, intended to help dismantle Soviet nuclear weapons and reduce proliferation risks. More recently, the corporation addressed interethnic and regional conflict and funded projects seeking to diminish the risks of a wider war resulting from civil strife. Two Carnegie commissions, Reducing the Nuclear Danger (1990), the other Preventing Deadly Conflict (1994), addressed the dangers of human conflict and the use of weapons of mass destruction. The corporation's emphasis in Commonwealth Africa, meanwhile, shifted to women's health and political development and the application of science and technology, including new information systems, to foster research and expertise in indigenous scientific institutions and universities.

During Hamburg's tenure, dissemination achieved even greater primacy with respect to strategic philanthropy. Consolidation and diffusion of the best available knowledge from social science and education research was used to improve social policy and practice, as partner with major institutions with the capability to influence public thought and action. If "change agent" was a major term during Pifer's time, "linkage" became a byword in Hamburg's. The corporation increasingly used its convening powers to bring together experts across disciplinary and sectoral boundaries to create policy consensus and promote collaboration.

Continuing tradition, the foundation established several other major study groups, often directed by the president and managed by a special staff. Three groups covered the educational and developmental needs of children and youth from birth to age fifteen: the Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development (1986), the Carnegie Task Force on Meeting the Needs of Young Children (1991), and the Carnegie Task Force on Learning in the Primary Grades (1994). Another, the Carnegie Commission on Science, Technology, and Government (1988), recommended ways that government at all levels could make more effective use of science and technology in their operations and policies. Jointly with the Rockefeller Foundation, the corporation financed the National Commission on Teaching & America's Future, whose report, What Matters Most (1996), provided a framework and agenda for teacher education reform across the country. These study groups drew on knowledge generated by grant programs and inspired follow-up grantmaking to implement their recommendations.

Vartan Gregorian

During the presidency of Vartan Gregorian the corporation reviewed its management structure and grants programs. In 1998 the corporation established four primary program headings: education, international peace and security, international development, and democracy. In these four main areas, the corporation continued to engage with major issues confronting higher education. Domestically, it emphasized reform of teacher education and examined the current status and future of liberal arts education in the United States. Abroad, the corporation sought to devise methods to strengthen higher education and public libraries in Commonwealth Africa. As a cross-program initiative, and in cooperation with other foundations and organizations, the corporation instituted a scholars program, offering funding to individual scholars, particularly in the social sciences and humanities, in the independent states of the former Soviet Union.

Honours

• Honorary-Member of the Order of Liberty, Portugal (5 April 2018)[15]

See also

• Carnegie Commission on the Poor White Problem in South Africa

• Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

• Carnegie library

• Andrew Carnegie

• Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

• Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

• The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

• Nicholas Murray Butler

Footnotes

1. "Annual Report 2018" (PDF). Carnegie Corporation of New York. Carnegie Corporation of New York. 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

2. Carnegie Corporation of New York

3. "Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies". Kathryn W. and Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University. Harvard University. 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

4. Gary Mulholland; Claire MacEachen; Ilias Kapareliotis (2013). Charles Wankel, Ph.D.; Larry E. Pate (eds.). Rise, Fall, Re-Emergence of Social Enterprise. Social Entrepreneurship as a Catalyst for Social Change: Research in Management Education and Development. Information Age Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1623964474.

5. "Food Research Institute". Stanford University.

6. Richard Glotzer, "A long shadow: Frederick P. Keppel, the Carnegie Corporation and the Dominions and Colonies Fund Area Experts 1923–1943." History of Education 38.5 (2009): 621-648.

7. Walter Jackson, "The Making of a Social Science Classic: Gunnar Myrdal's An American Dilemma." Perspectives in American History 2 (1985): 221-67.

8. The Silent War: Imperialism and the Changing Perception of Race By Frank Füredi. Page 66-67. ISBN 0-8135-2612-4

9. Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History By Ann Laura Stoler. Page 66. ISBN 0-8223-3724-X

10. Racially segregated school libraries in KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa by Jennifer Verbeek. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, Vol. 18, No. 1, 23-46 (1986)

11. The American Century: Consensus and Coercion in the Projection of American Power By David Slater and Peter James Taylor. Page 290. ISBN 0-631-21222-1, 1999

12. "History". Kathryn W. and Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University. Harvard University.

13. Elizabeth L. Cless, "The Birth of an Idea: An Account of the Genesis of Women's Continuing Education," in Helen S. Astin (ed.), Some Action of Her Own: The Adult Woman and Higher Education, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1976, pp.6-7.

14. Ellen Condliffe Lagemann (1992). The Politics of Knowledge: The Carnegie Corporation, Philanthropy, and Public Policy. University of Chicago Press. p. 183. ISBN 0226467805 – via Google Books.

15. "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas". Página Oficial das Ordens Honoríficas Portuguesas. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

Further reading

• Sara L. Engelhardt (ed.), The Carnegie Trusts and Institutions. New York: Carnegie Corporation of New York, 1981.

• Ellen C. Lagemann, The Politics of Knowledge. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1989.

• Inderjeet Parmar, Foundations of the American Century: The Ford, Carnegie, and Rockefeller Foundations in the Rise of American Power. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

• Patricia L Rosenfield, "A world of giving : Carnegie Corporation of New York-- a Century of International Philanthropy." New York : PublicAffairs, 2014.

External links

• Carnegie Corporation of New York

• History of the Carnegie Corporation

• Carnegie Corporation of New York archives at Columbia University

• Time For Ford Foundation & CFR To Divest? Collaboration of the Rockefeller, Ford and Carnegie Foundations with the Council on Foreign Relations