David Ricardoby Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/22/20

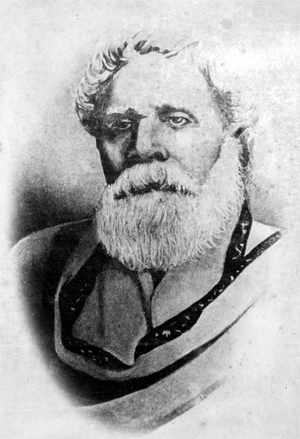

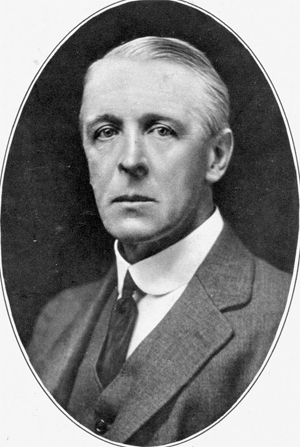

The Right Honourable David Ricardo

Portrait of David Ricardo by Thomas Phillips, circa 1821. This painting shows Ricardo, aged 49, two years before his death.

Member of Parliament for Portarlington

In office: 20 February 1819 – 11 September 1823

Preceded by: Richard Sharp

Succeeded by: James Farquhar

Personal details

Born: 18 April 1772, London, England

Died: 11 September 1823 (aged 51), Gatcombe Park, Gloucestershire, England

Nationality: British

Political party: Whig

Spouse(s): Priscilla Anne Wilkinson (m. 1793–1823)

Children: 6 children, including David the Younger

Profession: Businessman economist

Academic career, School or tradition: Classical economics

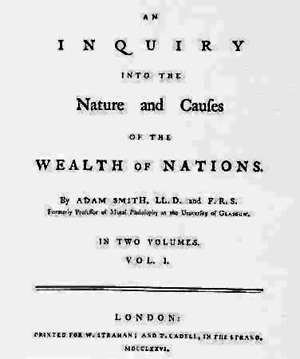

Influences: Smith · Bentham

Contributions: Ricardian equivalence, labour theory of value, comparative advantage, law of diminishing returns, Ricardian socialism, Economic rent[1]

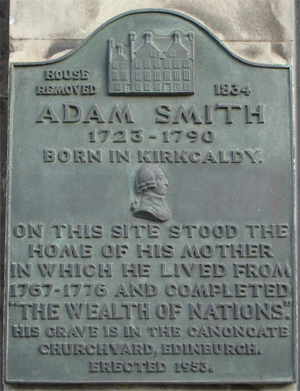

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, one of the most influential of the classical economists along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill.[2][3]

Personal lifeBorn in London, England, Ricardo was the third surviving of the 17 children of Abigail Delvalle (1753–1801) and her husband Abraham Israel Ricardo (1733?–1812).[4] His family were Sephardic Jews of Portuguese origin who had recently relocated from the Dutch Republic.[5] His father was a successful stockbroker[5] and Ricardo began working with him at the age of 14. At the age of 21, Ricardo eloped with a Quaker, Priscilla Anne Wilkinson, and, against his father's wishes, converted to the Unitarian faith.[6] This religious difference resulted in estrangement from his family, and he was led to adopt a position of independence.[7] His father disowned him and his mother apparently never spoke to him again.[8]

Following this estrangement he went into business for himself with the support of Lubbocks and Forster, an eminent banking house. He made the bulk of his fortune as a result of speculation on the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo. The Sunday Times reported in Ricardo's obituary, published on 14 September 1823, that during the Battle of Waterloo Ricardo "netted upwards of a million sterling", a huge sum at the time. He immediately retired, his position on the floor no longer tenable, and subsequently purchased Gatcombe Park, an estate in Gloucestershire, now owned by Princess Anne, the Princess Royal and retired to the country. He was appointed High Sheriff of Gloucestershire for 1818–19.[9]

In August 1818 he bought Lord Portarlington's seat in Parliament for £4,000, as part of the terms of a loan of £25,000. His record in Parliament was that of an earnest reformer. He held the seat until his death five years later.

Ricardo was a close friend of James Mill. Other notable friends included Jeremy Bentham and Thomas Malthus, with whom Ricardo had a considerable debate (in correspondence) over such things as the role of landowners in a society. He also was a member of Malthus' Political Economy Club, and a member of the King of Clubs. He was one of the original members of The Geological Society.[8] His youngest sister was author Sarah Ricardo-Porter (e.g., Conversations in Arithmetic).

Parliamentary recordHe voted with the opposition in support of the liberal movements in Naples, 21 February, and Sicily, 21 June, and for inquiry into the administration of justice in Tobago, 6 June. He divided for repeal of the Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act, 8 May, inquiry into the Peterloo massacre, 16 May, and abolition of the death penalty for forgery, 25 May, 4 June 1821.

He adamantly supported the implementation of free trade. He voted against renewal of the sugar duties, 9 Feb, and objected to the higher duty on East as opposed to West Indian produce, 4 May 1821. He opposed the timber duties. He voted silently for parliamentary reform, 25 Apr 3 June, and spoke in its favour at the Westminster anniversary reform dinner, 23 May 1822. He again voted for criminal law reform, 4 June.

His friend John Louis Mallett commented: " … he meets you upon every subject that he has studied with a mind made up, and opinions in the nature of mathematical truths. He spoke of parliamentary reform and ballot as a man who would bring such things about, and destroy the existing system tomorrow, if it were in his power, and without the slightest doubt on the result … It is this very quality of the man’s mind, his entire disregard of experience and practice, which makes me doubtful of his opinions on political economy."

Death and legacyTen years after retiring and four years after entering Parliament Ricardo died from an infection of the middle ear that spread into his brain and induced septicaemia. He was 51.

He and his wife Priscilla had eight children together including Osman Ricardo (1795–1881; MP for Worcester 1847–1865), David Ricardo (1803–1864, MP for Stroud 1832–1833) and Mortimer Ricardo, who served as an officer in the Life Guards and was a deputy lieutenant for Oxfordshire.[10]

Ricardo is buried in an ornate grave in the churchyard of Saint Nicholas in Hardenhuish, now a suburb of Chippenham, Wiltshire. At the time of his death his assets were estimated at between £675,000–£775,000.[4]

IdeasHe wrote his first economics article at age 37, firstly in The Morning Chronicle advocating reduction in the note-issuing of the Bank of England and then publishing The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes in 1810.[11]

He was also an abolitionist, speaking at a meeting of the Court of the East India Company in March 1823, where he said he regarded slavery as a stain on the character of the nation.[12]

Value theoryRicardo's most famous work is his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817). He advanced a labor theory of value:[13]

The value of a commodity, or the quantity of any other commodity for which it will exchange, depends on the relative quantity of labour which is necessary for its production, and not on the greater or less compensation which is paid for that labour.

Ricardo's note to Section VI:[14]

Mr. Malthus appears to think that it is a part of my doctrine, that the cost and value of a thing be the same;—it is, if he means by cost, "cost of production" including profit.

RentMain article: Law of rent

Ricardo contributed to the development of theories of rent, wages, and profits. He defined rent as "the difference between the produce obtained by the employment of two equal quantities of capital and labor." Ricardo believed that the process of economic development, which increased land utilization and eventually led to the cultivation of poorer land, principally benefited landowners. According to Ricardo, such premium over "real social value" that is reaped due to ownership constitutes value to an individual but is at best[15] a paper monetary return to "society". The portion of such purely individual benefit that accrues to scarce resources Ricardo labels "rent".

Ricardo's theories of wages and profitsIn his Theory of Profit, Ricardo stated that as real wages increase, real profits decrease because the revenue from the sale of manufactured goods is split between profits and wages. He said in his Essay on Profits, "Profits depend on high or low wages, wages on the price of necessaries, and the price of necessaries chiefly on the price of food."

Ricardian theory of international tradeBetween 1500 and 1750 most economists advocated Mercantilism which promoted the idea of international trade for the purpose of earning bullion by running a trade surplus with other countries. Ricardo challenged the idea that the purpose of trade was merely to accumulate gold or silver. With "comparative advantage" Ricardo argued in favour of industry specialisation and free trade. He suggested that industry specialization combined with free international trade always produces positive results. This theory expanded on the concept of absolute advantage.

Ricardo suggested that there is mutual national benefit from trade even if one country is more competitive in every area than its trading counterpart and that a nation should concentrate resources only in industries where it has a comparative advantage,[16] that is in those industries in which it has the greatest competitive edge. Ricardo suggested that national industries which were, in fact, profitable and internationally competitive should be jettisoned in favour of the most competitive industries, the assumption being that subsequent economic growth would more than offset any economic dislocation which would result from closing profitable and competitive national industries.

Ricardo attempted to prove theoretically that international trade is always beneficial.[17] Paul Samuelson called the numbers used in Ricardo's example dealing with trade between England and Portugal the "four magic numbers".[18] "In spite of the fact that the Portuguese could produce both cloth and wine with less amount of labor, Ricardo suggested that both countries would benefit from trade with each other".

As for recent extensions of Ricardian models, see Ricardian trade theory extensions.

Comparative advantageRicardo's theory of international trade was reformulated by John Stuart Mill.[19] The term "comparative advantage" was started by J. S. Mill and his contemporaries.

John Stuart Mill started a neoclassical turn of international trade theory, i.e. his formulation was inherited by Alfred Marshall and others and contributed to the resurrection of anti-Ricardian concept of law of supply and demand and induce the arrival neoclassical theory of value.[20]

New interpretationRicardo's four magic numbers has long been interpreted as comparison of two ratios of labor input coefficients. This interpretation is now considered as erroneous. This point was first made by Roy J. Ruffin[21] in 2002 and examined and explained in detail in Andrea Maneschi[22] in 2004. This is now known as new interpretation but it has been mentioned by P. Sraffa in 1930 and by Kenzo Yukizawa in 1974.[23] The new interpretation affords totally new reading of Ricardo's Principles of Political Economy and Taxation with regards to trade theory.[24]

ProtectionismLike Adam Smith, Ricardo was an opponent of protectionism for national economies, especially for agriculture. He believed that the British "Corn Laws" – imposing tariffs on agricultural products – ensured that less-productive domestic land would be cultivated and rents would be driven up (Case & Fair 1999, pp. 812, 813). Thus, profits would be directed toward landlords and away from the emerging industrial capitalists. Ricardo believed landlords tended to squander their wealth on luxuries, rather than invest. He believed the Corn Laws were leading to the stagnation of the British economy.[25] In 1846, his nephew John Lewis Ricardo, MP for Stoke-upon-Trent, advocated free trade and the repeal of the Corn Laws.

Modern empirical analysis of the Corn Laws yields mixed results.[26] Parliament repealed the Corn Laws in 1846.

Technological changeRicardo was concerned about the impact of technological change on labor in the short-term.[27] In 1821, he wrote that he had become "convinced that the substitution of machinery for human labour, is often very injurious to the interests of the class of labourers," and that "the opinion entertained by the labouring class, that the employment of machinery is frequently detrimental to their interests, is not founded on prejudice and error, but is conformable to the correct principles of political economy."[27]

Criticism of the Ricardian theory of tradeRicardo himself was the first to recognize that comparative advantage is a domain-specific theory, meaning that it applies only when certain conditions are met. Ricardo noted that the theory applies only in situations where capital is immobile. Regarding his famous example, he wrote:

it would undoubtedly be advantageous to the capitalists [and consumers] of England… [that] the wine and cloth should both be made in Portugal [and that] the capital and labour of England employed in making cloth should be removed to Portugal for that purpose.[28]

Ricardo recognized that applying his theory in situations where capital was mobile would result in offshoring, and thereby economic decline and job loss. To correct for this, he argued that (i) most men of property [will be] satisfied with a low rate of profits in their own country, rather than seek[ing] a more advantageous employment for their wealth in foreign nations, and (ii) that capital was functionally immobile.[28]

Ricardo's argument in favour of free trade has also been attacked by those who believe trade restriction can be necessary for the economic development of a nation. Utsa Patnaik claims that Ricardian theory of international trade contains a logical fallacy. Ricardo assumed that in both countries two goods are producible and actually are produced, but developed and underdeveloped countries often trade those goods which are not producible in their own country. In these cases, one cannot define which country has comparative advantage.[29]

Critics also argue that Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage is flawed in that it assumes production is continuous and absolute. In the real world, events outside the realm of human control (e.g. natural disasters) can disrupt production. In this case, specialisation could cripple a country that depends on imports from foreign, naturally disrupted countries. For example, if an industrially based country trades its manufactured goods with an agrarian country in exchange for agricultural products, a natural disaster in the agricultural country (e.g. drought) may cause the industrially based country to starve.

As Joan Robinson pointed out, following the opening of free trade with England, Portugal endured centuries of economic underdevelopment: "the imposition of free trade on Portugal killed off a promising textile industry and left her with a slow-growing export market for wine, while for England, exports of cotton cloth led to accumulation, mechanisation and the whole spiralling growth of the industrial revolution". Robinson argued that Ricardo's example required that economies be in static equilibrium positions with full employment and that there could not be a trade deficit or a trade surplus. These conditions, she wrote, were not relevant to the real world. She also argued that Ricardo's math did not take into account that some countries may be at different levels of development and that this raised the prospect of 'unequal exchange' which might hamper a country's development, as we saw in the case of Portugal.[30]

The development economist Ha-Joon Chang challenges the argument that free trade benefits every country:

Ricardo’s theory is absolutely right—within its narrow confines. His theory correctly says that, accepting their current levels of technology as given, it is better for countries to specialize in things that they are relatively better at. One cannot argue with that. His theory fails when a country wants to acquire more advanced technologies—that is, when it wants to develop its economy. It takes time and experience to absorb new technologies, so technologically backward producers need a period of protection from international competition during this period of learning. Such protection is costly, because the country is giving up the chance to import better and cheaper products. However, it is a price that has to be paid if it wants to develop advanced industries. Ricardo’s theory is, thus seen, for those who accept the status quo but not for those who want to change it.[31]

Ricardian equivalenceAnother idea associated with Ricardo is Ricardian equivalence, an argument suggesting that in some circumstances a government's choice of how to pay for its spending (i.e., whether to use tax revenue or issue debt and run a deficit) might have no effect on the economy. This is due to the fact the public saves its excess money to pay for expected future tax increases that will be used to pay off the debt. Ricardo notes that the proposition is theoretically implied in the presence of intertemporal optimisation by rational tax-payers: but that since tax-payers do not act so rationally, the proposition fails to be true in practice. Thus, while the proposition bears his name, he does not seem to have believed it. Economist Robert Barro is responsible for its modern prominence.

Influence and intellectual legacyDavid Ricardo's ideas had a tremendous influence on later developments in economics. US economists rank Ricardo as the second most influential economic thinker, behind Adam Smith, prior to the twentieth century.[32]

Ricardo became the theoretical father of classical political economy. However, Schumpeter coined an expression Ricardian vice, which indicates that rigorous logic does not provide a good economic theory.[33] This criticism applies also to most neoclassical theories, which make heavy use of mathematics, but are, according to him, theoretically unsound, because the conclusion being drawn does not logically follow from the theories used to defend it.[citation needed]

Ricardian socialistsMain article: Ricardian socialism

Ricardo's writings fascinated a number of early socialists in the 1820s, who thought his value theory had radical implications. They argued that, in view of labor theory of value, labor produces the entire product, and the profits capitalists get are a result of exploitations of workers.[34] These include Thomas Hodgskin, William Thompson, John Francis Bray, and Percy Ravenstone.GeorgistsGeorgists believe that rent, in the sense that Ricardo used, belongs to the community as a whole. Henry George was greatly influenced by Ricardo, and often cited him, including in his most famous work, Progress and Poverty from 1879. In the preface to the fourth edition, he wrote: "What I have done in this book, if I have correctly solved the great problem I have sought to investigate, is, to unite the truth perceived by the school of Smith and Ricardo to the truth perceived by the school of Proudhon and Lasalle; to show that laissez faire (in its full true meaning) opens the way to a realization of the noble dreams of socialism; to identify social law with moral law, and to disprove ideas which in the minds of many cloud grand and elevating perceptions."[35]Neo-RicardiansAfter the rise of the 'neoclassical' school, Ricardo's influence declined temporarily. It was Piero Sraffa, the editor of the Collected Works of David Ricardo[36] and the author of seminal Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities,[37] who resurrected Ricardo as the originator of another strand of economics thought, which was effaced with the arrival of the neoclassical school. The new interpretation of Ricardo and Sraffa's criticism against the marginal theory of value gave rise to a new school, now named neo-Ricardian or Sraffian school. Major contributors to this school includes Luigi Pasinetti (1930–), Pierangelo Garegnani (1930–2011), Ian Steedman (1941–), Geoffrey Harcourt (1931–), Heinz Kurz (1946–), Neri Salvadori (1951–), Pier Paolo Saviotti (–) among others. See also Neo-Ricardianism. The Neo-Ricardian school is sometimes seen to be a component of Post-Keynesian economics.

Neo-Ricardian trade theoryInspired by Piero Sraffa, a new strand of trade theory emerged and was named neo-Ricardian trade theory. The main contributors include Ian Steedman and Stanley Metcalfe. They have criticised neoclassical international trade theory, namely the Heckscher–Ohlin model on the basis that the notion of capital as primary factor has no method of measuring it before the determination of profit rate (thus trapped in a logical vicious circle).[38][39] This was a second round of the Cambridge capital controversy, this time in the field of international trade.[40] Depoortère and Ravix judge that neo-Ricardian contribution failed without giving effective impact on neoclassical trade theory, because it could not offer "a genuine alternative approach from a classical point of view."[41]

Evolutionary growth theorySeveral distinctive groups have sprung out of the neo-Ricardian school. One is the evolutionary growth theory, developed notably by Luigi Pasinetti, J.S. Metcalfe, Pier Paolo Saviotti, and Koen Frenken and others.[42][43]

Pasinetti[44][45] argued that the demand for any commodity came to stagnate and frequently decline, demand saturation occurs. Introduction of new commodities (goods and services) is necessary to avoid economic stagnation.

Contemporary theoriesMain article: International trade theory § Ricardian trade theory extensions

Ricardo's idea was even expanded to the case of continuum of goods by Dornbusch, Fischer, and Samuelson[46] This formulation is employed for example by Matsuyama[47] and others.

Ricardian trade theory ordinarily assumes that the labour is the unique input. This is a deficiency as intermediate goods are a great part of international trade. The situation changed after the appearance of Yoshinori Shiozawa's work of 2007.[48] He has succeeded to incorporate traded input goods in his model.[49]

Yeats found that 30% of world trade in manufacturing is intermediate inputs.[50] Bardhan and Jafee found that intermediate inputs occupy 37 to 38% in the imports to the US for the years from 1992 to 1997, whereas the percentage of intrafirm trade grew from 43% in 1992 to 52% in 1997.[51]

Unequal exchangeChris Edward includes Emmanuel's unequal exchange theory among variations of neo-Ricardian trade theory.[52] Arghiri Emmanuel argued that the Third World is poor because of the international exploitation[clarification needed] of labour.[53][verification needed]

The unequal exchange theory of trade has been influential to the (new) dependency theory.[54]

Publications[x]

Works, 1852Ricardo's publications included:

• The High Price of Bullion, a Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes (1810), which advocated the adoption of a metallic currency.

• Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock (1815), which argued that repealing the Corn Laws would distribute more wealth to the productive members of society.

• On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), an analysis that concluded that land rent grows as population increases. It also clearly laid out the theory of comparative advantage, which argued that all nations could benefit from free trade, even if a nation was less efficient at producing all kinds of goods than its trading partners.

His works and writings were collected in Ricardo, David (1981). The works and correspondence of David Ricardo (1st paperback ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521285054. OCLC 10251383.

References

Notes1. Miller, Roger LeRoy. Economics Today. Fifteenth Edition. Boston, MA: Pearson Education. p. 559

2. Sowell, Thomas (2006). On classical economics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

3. "David Ricardo | Policonomics".

4. Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004). "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. ref:odnb/23471. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23471. Retrieved 14 December 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

5. Heertje, Arnold (2004). "The Dutch and Portuguese-Jewish background of David Ricardo". European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 11 (2): 281–94. doi:10.1080/0967256042000209288.

6. Francisco Solano Constancio, Paul Henri Alcide Fonteyraud. 1847. Œuvres complètes de David Ricardo, Guillaumin, (pp. v–xlviii): A part sa conversion au Christianisme et son mariage avec une femme qu'il eut l'audace grande d'aimer malgré les ordres de son père

7. Ricardo, David. 1919. Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. G. Bell, p. lix: "by reason of a religious difference with his father, to adopt a position of independence at a time when he should have been undergoing that academic training"

8. Sraffa, Piero; David Ricardo (1955), The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo: Volume 10, Biographical Miscellany, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 434, ISBN 0-521-06075-3

9. "No. 17326". The London Gazette. 24 January 1818. p. 188.

10. "RICARDO, David (1772–1823), of Gatcombe Park, Minchinhampton, Glos. and 56 Upper Brook Street, Grosvenor Square, Mdx". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

11. Hayek, Friedrich (1991). "The Restriction Period, 1797–1821, and the Bullion Debate". The Trend of Economic Thinking. pp. 199–200. ISBN 978-0865977426.

12. King, John (2013). David Ricardo. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 48.

13. Ricardo, David (1817) On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Piero Sraffa (Ed.) Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, Volume I, Cambridge University Press, 1951, p. 11.

14. Ricardo, David (1817) On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Piero Sraffa (Ed.) Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, Volume I, Cambridge University Press, 1951, p. 47.

15. On The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street, by David Ricardo, 1817 (third edition 1821) – Chapter 6, On Profits: paragraph 28, "Thus, taking the former . . ." and paragraph 33, "There can, however...."

16. Roberts, Paul Craig (28 August 2003), "The Trade Question", The Washington Times

17. Ricardo, David (1817) On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Piero Sraffa (Ed.) Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, Volume I, Cambridge University Press, 1951, p. 135.

18. Samuelson, Paul A. (1972), "The Way of an Economist." Reprinted in The Collected Papers of Paul A. Samuelson. Ed. R. C. Merton. Cambridge: Cambridge MIT Press. p. 378.

19. Mill, J. S. (1844) Essays on some unsettled questions of political economy.London, John W. Parker; Mill, J. S. (1848) The principles of political economy. (vol. I and II) Boston: C.C.Little & J. Brown.

20. Shiozawa, Y. (2017) An Origin of the Neoclassicla Revolutions: Mill's "Reversion" and its consequences. In Shiozawa, Oka,and Tabuchi (eds.) A New Construction of Ricardian Theory of International Values, Tokyo: Springer Japan, Chapter 7 pp.191–243.

21. Ruffin, R.J. (2002) David Ricardo's discovery of comparative advantage. History of Political Economy 34(4): 727–748.

22. Maneschi, A. (2004) The true meaning of David Ricardo's four magic numbers. Journal of International Economics 62(2): 433–443.

23. Tabuchi, T. (2017) Yukizawa's interpretation of Ricardo's 'theory of comparative cost'. In Senga, Fujimoto, and Tabuchi (Eds.) Ricardo and International Trade, London and New York; Routledge, Chapter 4, pp.48–59.

24. Faccarello, G. (2017) A calm investigation into Mr. Ricardo's principle of international trade. In Senga, Fujimoto, and Tabuchi (Eds.) Ricardo and International Trade, London and New York; Routledge. Tabuchi, T. (2017) Comparative Advantage in the Light of the Old Value Theories. In Shiozawa, Oka,and Tabuchi (eds.) A New Construction of Ricardian Theory of International Values, Tokyo: Springer Japan, Chapter 9 pp.265–280.

25. Letter of Mill cited in The works and correspondence of David Ricardo. : Volume 9, Letters July 1821–1823 (Cambridge, UK, 1952)

26. Williamson, J. G. (1990). "The impact of the Corn Laws just prior to repeal". Explorations in Economic History. 27 (2): 123. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(90)90007-L.

27. Hollander, Samuel (2019). "Retrospectives Ricardo on Machinery". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 33 (2): 229–242. doi:10.1257/jep.33.2.229. ISSN 0895-3309.

28. Ricardo, David (1821). On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. John Murray. p. 7.19.

29. Patnaik, Uta (2005). "Ricardo's Fallacy/ Mutual Benefit from Trade Based on Comparative Costs and Specialization?". In Jomo, K. S. (ed.). The Pioneers of Development Economics: Great Economists on Development. London and New York: Zed books. pp. 31–41. ISBN 81-85229-99-6.

30. Robinson, Joan (1979). Aspects of Development and Underdevelopment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 0521226376.

31. Chang, Ha-Joon (2007), "Bad Samaritans", Chapter 2, pp. 30–31.

32. Davis, William L., Bob Figgins, David Hedengren, and Daniel B. Klein. "Economics Professors' Favorite Economic Thinkers, Journals and Blogs (along with Party and Policy Views)," Econ Journal Watch 8(2): 126–46, May 2011 [1].

33. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, (published posthumously, ed. Elisabeth Boody Schumpeter), 1954. pp. 569, 1171. Schumpeter also criticized J. M. Keynes for committing the same Ricardian vice.

34. Landreth Colander 1989 History of Economic Thought Second Edition, p.137.

35. George, Henry, Progress and Poverty. Preface to the 4th Edition, November 1880.

36. Piero Sraffa and M.H. Dobb, editors (1951–1973). The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo. Cambridge University Press, 11 volumes.

37. Sraffa, Piero 1960, Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities: Prelude to a Critique of Economic Theory. Cambridge University Press.

38. Steedman, Ian, ed. (1979). Fundamental Issues in Trade Theory. London: MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-25834-7.

39. Steedman, Ian (1979). Trade Amongst Growing Economies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. [, page needed], . ISBN 0-521-22671-6.

40. Edwards, Chris (1985). "§ 3.2 The 'Sraffian' Approach to Trade Theory". The Fragmented World: Competing Perspectives on Trade, Money, and Crisis. London and New York: Methuen & Co. pp. 48–51. ISBN 0-416-73390-5.

41. Christophe Depoortère, Joël Thomas Ravix 2015 The classical theory of international trade after Sraffa. Cahiers d'économie Politique / Papers in Political Economy (69): 203–34, February 2015.

42. Pasinetti, Luisi 1981 Structural change and economic growth, Cambridge University Press. J.S. Metcalfe and P.P. Saviotti (eds.), 1991, Evolutionary Theories of Economic and Technological Change, Harwood, 275 pages. J.S. Metcalfe 1998, Evolutionary Economics and Creative Destruction, Routledge, London. Frenken, K., Van Oort, F.G., Verburg, T., Boschma, R.A. (2004). Variety and Regional Economic Growth in the Netherlands – Final Report (The Hague: Ministry of Economic Affairs), 58 p. (pdf)

43. Saviotti, Pier Paolo; Frenken, Koen (2008), "Export variety and the economic performance of countries", Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18 (2): 201–18, doi:10.1007/s00191-007-0081-5

44. Pasinetti, Luigi L. (1981), Structural change and economic growth: a theoretical essay on the dynamics of the wealth of nations, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. [, page needed], , ISBN 0-521-27410-9

45. Pasinetti, Luigi L. (1993), Structural economic dynamics: a theory of the economic consequences of human learning, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. [, page needed], , ISBN 0-521-43282-0

46. Dornbusch, R.; Fischer, S.; Samuelson, P. A. (1977), "Comparative Advantage, Trade, and Payments in a Ricardian Model with a Continuum of Goods" (PDF), The American Economic Review, 67 (5): 823–39, JSTOR 1828066, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011

47. Matsuyama, K. (2000), "A Ricardian Model with a Continuum of Goods under Nonhomothetic Preferences: Demand Complementarities, Income Distribution, and North–South Trade" (PDF), Journal of Political Economy, 108 (6): 1093–120, doi:10.1086/317684.

48. Shiozawa, Y. (2007). "A New Construction of Ricardian Trade Theory: A Multi-country, Multi-commodity Case with Intermediate Goods and Choice of Production Techniques". Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review. 3 (2): 141–87. doi:10.14441/eier.3.141.

49. Y. Shiozawa (2017) The new theory of international values: An overview. Shiozawa, Oka and Tabuchi (eds.) A New Construction of Ricardian Theory of International Values. Singapore: Springer. Chapter 1, pp.3–73.

50. Yeats, A. (2001). "Just How Big is Global Production Sharing?". In Arndt, S.; Kierzkowski, H. (eds.). Fragmentation: New Production Patterns in the World Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924331-X.

51. Bardhan, Ashok Deo; Jaffee, Dwight (2004). "On Intra-Firm Trade and Multinationals: Foreign Outsourcing and Offshoring in Manufacturing". In Graham, Monty; Solow, Robert (eds.). The Role of Foreign Direct Investment and Multinational Corporations in Economic Development.[verification needed]

52. Chris Edwards 1985 The Fragmented World: Competing Perspectives on Trade, Money and Crisis, London and New York: Methuen. Chapter 4.

53. Emmanuel, Arghiri (1972), Unequal exchange; a study of the imperialism of trade, New York: Monthly Review Press, pp. [, page needed], , ISBN 0-85345-188-5

54. Palma, G (1978), "Dependency: A formal theory of underdevelopment or a methodology for the analysis of concrete situations of underdevelopment?", World Development, 6 (7–8): 881–924, doi:10.1016/0305-750X(78)90051-7

Bibliography

By David Ricardo• Case, Karl E.; Fair, Ray C. (1999), Principles of Economics (5th ed.), Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-961905-4

• Samuel Hollander (1979). The Economics of David Ricardo. University of Toronto Press.

• G. de Vivo (1987). "Ricardo, David," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 183–98

• Samuelson, P.A. (2001), "Ricardo, David (1772–1823)", International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, pp. 13330–13334, doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/00324-7, ISBN 9780080430768

• (in French) Éric Pichet, David RICARDO, le premier théoricien de l'économie, Les éditions du siècle, 2004*

External links• Works by David Ricardo at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about David Ricardo at Internet Archive

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by David Ricardo

• Biography at New School University

• Biography at EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic History

• Ricardo on Value: the Three Chapter Ones. A presentation tracing the changes in the Principles' (University of Southampton).