Scottish Church Collegeby Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/22/20

Scottish Church College

Former names: 1830: General Assembly's Institution; 1843: Free Church Institution; 1863: Duff College; 1908: Scottish Churches College; 1929: Scottish Church College

Motto: Nec Tamen Consumebatur[1] (Latin)

Motto in English: "The bush burns, but is not consumed"

Type: Private

Established: 13 July 1830; 189 years ago

Founder: Alexander Duff

Religious affiliation: Church of North India, Presbyterian

Academic affiliation: University of Calcutta

Principal: Dr. Arpita Mukerji

Administrative staff: 164

Undergraduates: 1518 (As of 2016–17)

Postgraduates: 97 (As of 2017–18)

Address: 1 & 3, Urquhart Square, Manicktala, Azad Hind Bag, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

22.54837°N 88.35596°ECoordinates: 22.54837°N 88.35596°E

Campus: Urban

Language: English, Bengali, Hindi

Nickname: The Caledonians

Website

http://www.scottishchurch.ac.in

Scottish Church College is a premier institute for pursuing undergraduate and postgraduate studies and is

the oldest continuously running Christian liberal arts and sciences college in India.[2][3] It has been rated (A) by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council, an autonomous organization that evaluates academic institutions in India.

It is affiliated with the University of Calcutta for degree courses for graduates and postgraduates. It is a selective coeducational institution, known for its high academic standards. Students and alumni call themselves "Caledonians" in the name of the college festival, "Caledonia".

The founder and institutional origins

Principals of General Assembly's Institution (1830–1908)•

Alexander Duff 1830–34• W. S. Mackay and D. Ewart 1834–39

• Alexander Duff 1840–43

• James Ogilvie, 1845–71

• William Hastie, 1878–84

• W. Smith, 1884–89

• John Morrison 1889–1904

• A. B. Wann, 1904–1908

Principal of Free Church Institution (1843–63)• Alexander Duff 1843–63

Principals of Duff College (1863–1908)• W. C. Fyffe, 1863–80

• James Robertson, 1881–83

• John Hector, 1883–1902

Principals of Scottish Churches College (1908–1929)• A.B. Wann, 1908–09

• John Lamb, 1909–11

• Alexander Tomory, 1910–1911

• James Watt, 1911–1928

Principals of Scottish Church College (1929–present)• W. S. Urquhart, 1928–37

• Allen Cameron, 1937–44

• John Kellas, 1944–54

• H. J. Taylor, 1954–60

• N. K. Mundle, 1960–70

• Jyotsna Pyne, 1970

• B. Das, 1970–1971

• S. K. Mitra, 1971–73

• K. D. Bhatt, 1973–75

• S. K. Mukherjee, 1975–76

• A. K. Sen, 1976–78

• A. K. Kisku, 1978–81

• Aparesh Bhattacharyya, 1981–1983

• Kalyan Chandra Dutt, 1983–1995

• Kalyan Kumar Mandi, 1996–2002

• John Abraham, 2002 – 2013

• John Abraham, 2013 – (Rector)

• Amit Abraham, 2015 – 2016

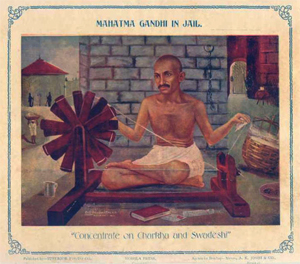

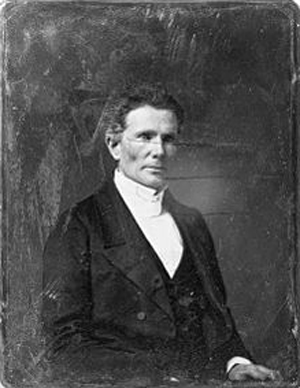

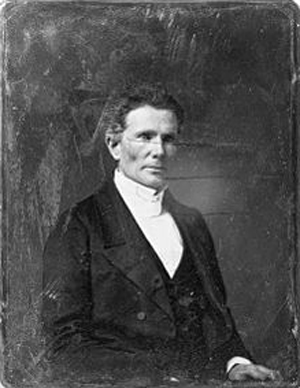

The foundationThe origins are traceable to the life of Alexander Duff (1806–1878), the first overseas missionary of the Church of Scotland, to India. Known initially as the General Assembly's Institution, it was founded on 13 July 1830.[4]

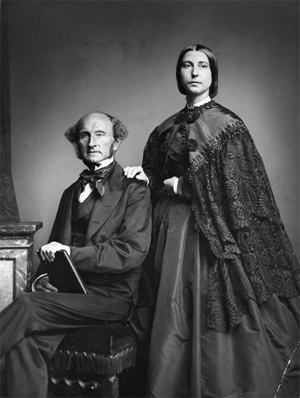

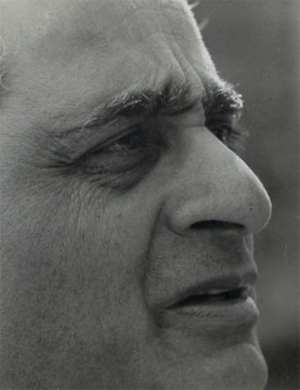

Alexander Duff

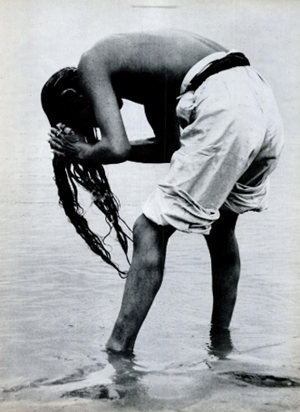

Alexander DuffAlexander Duff was born on 25 April 1806, in Moulin, Perthshire, located in the Scottish countryside. He attended the University of St Andrews where after graduation, he opted for a missionary life.[4] Subsequently, he undertook his evangelical mission to India.

In a voyage that involved two shipwrecks (first on the ship Lady Holland off Dassen Island, near Cape Town, and later on the ship Moira, near the Ganges delta) and the loss of his personal library consisting of 800 volumes (of which 40 survived), and college prizes, he arrived in Calcutta on 27 May 1830.[5][6]

Feringhi Kamal BoseSupported by the Governor-General of India Lord William Bentinck,[5] Rev. Alexander Duff opened his institution in Feringhi Kamal Bose's house, located in upper Chitpore Road, near Jorasanko. In 1836 the institution was moved to Gorachand Bysack's house at Garanhatta.[4] Mr. MacFarlane, the Chief-Magistrate of Calcutta, laid the foundation stone on 23 February 1837. Mr. John Gray, elected by Messrs. Burn & Co. and superintended by Captain John Thomson of the East India Company designed the building. It is possible that he may have been inspired by the facade of the Holy House of Mercy in Macau, which reflects the influence of Portuguese ⁰. Traces of English Palladianism are also evident in the design of the college. The construction of the building was completed in 1839.[4]

Historical contextIn the early 1800s, under the regime of the East India Company, English education and Missionary activities were initially suspect.[4] While the East India Company supported Orientalist instruction in the vernacular languages like Persian, Arabic and Sanskrit, and helped to establish institutions like Calcutta Madrasah College, and

Sanskrit College, in general, colonial administrative policy discouraged the dissemination of knowledge in their language, that is in English. The general apathy of the Company towards the cause of education and improvement of natives is in many ways, the background for the agency of missionaries like Duff.[7]

Inspired by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, Reverend Alexander Duff, then a young missionary, arrived in India's colonial capital to set up an English-medium institution. Though Bengalis had shown some interest in the spread of Western education from the beginning of the 19th century, both the local church and government officers were skeptical about the high-caste Bengali's response to the idea of an English-medium institution.[4]

While Orientalists like James Prinsep were supportive of the idea of vernacular education, Duff and prominent Indians like Raja Ram Mohan Roy supported the use of English as a medium of instruction.[4] His emphasis on the use of English on Indian soil was prophetic:

The English language, I repeat it, is the lever which, as the instrument of conveying the entire range of knowledge, is destined to move all Hindustan.[8]

Raja Ram Mohan Roy helped Duff by organizing the venue and bringing in the first batch of students. He also assured the guardians that reading the King James's Bible did not necessarily imply religious conversion, unless that was based on inner spiritual conviction. Imbibing the tenets of the Scottish educational system that shaped his ideals, Duff was, unlike the missionaries and scholars at the Serampore College, wholeheartedly committed to the cause of instruction in the English language, as that facilitated the advanced study of European religion, literature and science. By carefully selecting teachers, European and Indian, who brought out the best of Christian and secular understandings, and by emphasizing advanced pedagogical techniques that emphasized the Socratic method of classroom debate, inquiry, and rational thinking, Duff and his followers established an educational system, whose impact in spreading progressive values in contemporary Bengal would be profound.[9] Although his ultimate aim was the spread of English education, Duff was aware that a foreign language could not be mastered without command of the native language. Hence in his General Assembly's Institution (as later in his Free Church Institution), teaching and learning in the dominant vernacular Bengali language was also emphasized. Duff and his successors also underscored the necessity of sports among his students.[10] When he introduced political economy as a subject in the curricula, his faced his church's criticism.

The great social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy supported Reverend Duff in his efforts.In 1840, Duff returned to India. At the Disruption of 1843, Duff sided with the Free Church. He gave up the college buildings, with all their effects and established a new institution, called the Free Church Institution.[5] He had the support of Sir James Outram

The great social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy supported Reverend Duff in his efforts.In 1840, Duff returned to India. At the Disruption of 1843, Duff sided with the Free Church. He gave up the college buildings, with all their effects and established a new institution, called the Free Church Institution.[5] He had the support of Sir James Outram ...

Lieutenant-General Sir James Outram, 1st Baronet, GCB, KCSI (29 January 1803 – 11 March 1863) was an English general who fought in the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

-- Sir James Outram, 1st Baronet, by Wikipedia

and Sir Henry Lawrence,...

Brigadier-General Sir Henry Montgomery Lawrence KCB (28 June 1806 – 4 July 1857) was a British military officer, surveyor, administrator and statesman in British India. He is best known for leading a group of administrators in the Punjab affectionately known as Henry Lawrence's "Young Men", as the founder of the Lawrence Military Asylums and for his death at the Siege of Lucknow during

the Indian Rebellion.

-- Henry Montgomery Lawrence, by Wikipedia

and the encouragement of seeing

a new band of converts, including several young men born of high caste. In 1844, governor-general Viscount Hardinge opened government appointments to all who had studied in institutions similar to Duff's institution. In the same year, Duff co-founded the Calcutta Review, of which he served as editor from 1845 to 1849.The Calcutta Review is a bi-annual periodical, now published by the Calcutta University press, featuring scholarly articles from a variety of disciplines.

The Calcutta Review was founded in May 1844, by Sir John William Kaye and

Reverend Alexander Duff. Through the journal, Sir John Kaye aimed "to bring together such useful information, and propagate such sound opinions, relating to Indian affairs, as will, it is hoped, conduce, in some small measure, directly or indirectly, to the amelioration of the condition of the people".[1]

The periodical proved to be successful, and was published as a quarterly up until 1912. Sir John Kaye was Editor of four issues, and then retired due to ill health. He remained the owner of the review until 1855, when it was purchased by Meredith Townsend. Thacker, Spink and Company bought it in 1857. It was printed by Sanders and Cowes until 1857, when it moved to the Serampore Press. When Rev. T. Ridsdale took over as editor, it was published by R. C. Lepage and Company.

The journal was not published in 1912. In its second series, from 1913 to 1920, it was published bi-annually. In 1921, it was acquired by the Calcutta University press, which now releases it bi-annually.

-- Calcutta Review, by Wikipedia

In 1857, when the University of Calcutta was established, the Free Church Institution was one of its earliest affiliates, and Duff would also serve in the university's first senate.[11] These two institutions founded by Duff, i.e., the General Assembly's Institution and the Free Church Institution would be merged later to form the Scottish Churches College. After the unification of the Church of Scotland in 1929, the institution would be known as Scottish Church College.[4]

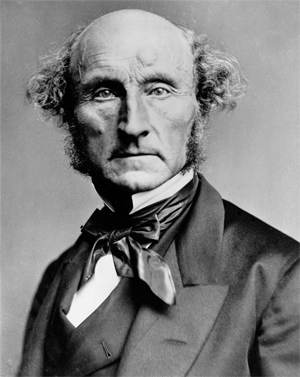

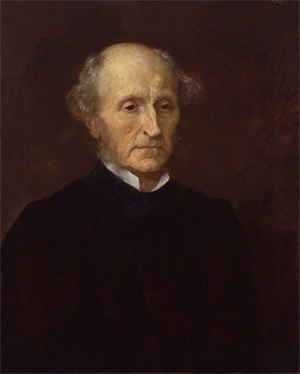

Along with Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the great social reformer often called the father of modern India, Dr. Duff supported Lord Macaulay in drafting his influential Minute for the introduction of English education in India. Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, FRS FRSE PC (25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician. He wrote extensively as an essayist, on contemporary and historical sociopolitical subjects, and as a reviewer. His The History of England was a seminal and paradigmatic example of Whig historiography, and its literary style has remained an object of praise since its publication, including subsequent to the widespread condemnation of its historical contentions which became popular in the 20th century.

Macaulay served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1848. He played a major role in the introduction of English and western concepts to education in India, and published his argument on the subject in the "Macaulay's Minute" in 1835. He supported the replacement of Persian by English as the official language, the use of English as the medium of instruction in all schools, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers. On the flip side, this led to Macaulayism in India, and the systematic wiping out of traditional and ancient Indian education and vocational systems and sciences.

Macaulay divided the world into civilised nations and barbarism, with Britain representing the high point of civilisation. In his Minute on Indian Education of February 1835, he asserted, "It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgement used at preparatory schools in England". He was wedded to the idea of progress, especially in terms of the liberal freedoms. He opposed radicalism while idealising historic British culture and traditions.

-- Thomas Babington Macaulay, by Wikipedia

Eminent contemporary and successive missionary scholars from Scotland, notably Dr. Ogilvie, Dr. Hastie,[12] Dr. Macdonald, Dr. Stephen, Dr. Watt, and Dr. Urquhart contributed in spreading liberal Western education.

The institutions founded by Duff have been coterminous with other contemporary institutions like the Serampore College, and the Hindu College in ushering the spirit of intellectual inquiry and a general acceptance of the ideals of the Enlightenment among Bengali Hindus, the then dominant indigenous ethno-linguistic group in the Company-administered Indian territories. This exchange of ideas and ideals, and adoption of

progressive values that would eventually influence many social reform movements in South Asia, has been widely regarded by historians specializing in nineteenth century India, as the epochs of

the Young Bengal Movement and later, the Bengal Renaissance.[13]

Duff's contemporaries included Reverend Mackay, Reverend Ewart and Reverend Thomas Smith.

Till the early 20th century the norm was to bring teachers from Scotland, and this brought forth scholars like William Spence Urquhart, Henry Stephen, H.M. Percival etc. Indian scholars were also engaged as teachers by the college authorities, and the notable faculty includes names like

Surendranath Banerjee, Kalicharan Bandyopadhyay, Jnan Chandra Ghosh, Gouri Shankar Dey, Adhar Chandra Mukhopadhyay, Sushil Chandra Dutta, Mohimohan Basu, Sudhir Kumar Dasgupta, Nirmal Chandra Bhattacharya, Bholanath Mukhopadhyay and Kalidas Nag, all of whom had all contributed to enhancing the academic standards of the college.[13]

The college authorities played a pioneering role in promoting gender equality by emphasizing the significance of women's education.

During much of the nineteenth century, the college remained the only institution of its kind in the city of Calcutta (and indeed in the country) to promote the cause of co-education.[5][14] Female students comprise half the present roll strength of the college. With the added interest of the missionaries in educational work and social welfare,

the college stands as a monument to Indo-Scottish co-operation.Postage stampOn 27 September 1980, the Indian Postal Service released a commemorative stamp on the college.[15]

College Hymn

O God, our help in ages past,

Our hope for years to come,

Our shelter from the stormy blast,

And our eternal home.

Under the shadow of Thy throne,

Thy saints have dwelt secure;

Sufficient is Thine arm alone,

And our defence is sure.

Before the hills in order stood,

Or earth received her frame,

From everlasting Thou art God,

To endless years the same.

A thousand ages in Thy sight

Are like an evening gone;

Short as the watch that ends the night

Before the rising sun.

Time, like an ever-rolling steam,

Bears all its sons away;

They fly forgotten, as a dream

Dies at the opening day.

O God, our help in ages past,

Our hope for years to come,

Be Thou our guard while troubles last,

And our eternal home.

Departments and programmesUndergraduate programmesBachelor of Arts (Honours) / Bachelor of Business Administration (Honours) / Bachelor of Commerce (Honours) / Bachelor of Science (Honours)

Department of Bengali / Department of Business Administration / Department of Commerce / Department of Botany

Department of English / -- / -- / Department of Chemistry

Department of History / -- / -- / Department of Computer Science

Department of Philosophy / -- / -- / Department of Economics

Department of Political Science / -- / -- / Department of Mathematics

Department of Sanskrit / -- / -- / Department of Microbiology

-- / -- / -- / Department of Physics

-- / -- / -- / Department of Zoology

Postgraduate programmes• Bachelor of Education (postgraduate course for women students, offered by the Department of Teacher Education)

• Master of Science in Botany (previously an autonomous course, offered by the postgraduate section of the Department of Botany, now under University of Calcutta)

• Master of Science in Chemistry (previously an autonomous course, offered by the postgraduate section of the Department of Chemistry, now under University of Calcutta)

Campus and infrastructure

Buildings Scottish Church College main building

Scottish Church College main building Scottish Church College Assembly Hall

Scottish Church College Assembly HallThe college sits on an area of six acres. It operates in seven buildings and two campuses. The main campus consists of the main building, which is among others, one of the oldest masonry pieces in the city of Kolkata and an example of colonial architecture. This has been declared a 'Heritage Building' by the statutory body constituted by the Government of West Bengal and the Calcutta Municipal Corporation. It includes the college Assembly Hall and the air-conditioned seminar room used by the departments for holding extension lectures and seminars.

The main building houses the economics, history, political science, philosophy, zoology, botany, mathematics, English, Sanskrit and Bengali departments. A separate Science annex building houses the departments of physics and chemistry. Situated in the main campus, the central library of the college is computerized. The biological science departments are in possession of a museum and a 'poly-house'. The college is encompassed by a garden and a lawn. Many medicinal plants are grown in the garden under the care of the botany department. There are rare and non-native plants in the garden as well. The Scottish Church College campus is a 'green' campus with solar lighting.[16]

Scottish Church College Millennium Building

Scottish Church College Millennium BuildingThe second campus houses the Millennium Building and the Department of Teacher Education. The college auditorium, called the M.L. Bhaumik Auditorium, is fully air-conditioned and is located in the Millennium Building. It is named after Dr. Mani Lal Bhaumik, laser scientist and an alumnus of the college. The cultural activities, special programmes, and students’extension activities are held here. The Millennium Building houses the departments of microbiology, computer science and business administration. The commerce classes, held in the morning batch of the college, are present in the Millennium Building.

A separate building houses the department of teacher education.[16]

Track and fieldThe college playground is situated about a kilometer away from the college. It has a full length football field and two other medium-sized football grounds. A running track surrounds the field. A two storied permanent pavilion ('Watt Pavilion') stands there, with separate changing rooms for boys and girls, toilets and a store-room. The teacher-in-charge of physical education is provided residential accommodation in a part of the pavilion. Separate common rooms for male and female students, equipped with indoor game facilities like table tennis are available in the campus.[16]

Halls of residenceThe college has five hostels for its students, all of which are situated near the college. They have recreational common rooms with audio-visual equipment.

• Lady Jane Dundas Hostel (for female students)

• Students' Residence (for female students)

• Duff Hostel

• Wann Hostel

• Ogilvie Hostel[16]

College publicationsThe college publications are annual and consists of contributions from students and staffs.

• The Scottish Church College Magazine is published annually with contributions from past and present staff and students.

• The Scottish Herald is the college newsletter and is published annually.

• The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, a refereed international academic journal with an interdisciplinary approach which publishes research articles written by both experienced and young scholars all over the world, is annually published by the college. The journal discusses issues from points of view such as liberalism, empiricism, positivism, Marxism, structuralism, psychoanalysis, postmodernism, deconstruction, feminism, subaltern studies school and postcolonialism. The advisory board consists of personalities such as Amartya Sen, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Partha Chatterjee, Dipesh Chakrabarty and Amiya Kumar Bagchi.[13][15]

• Sanket, a short magazine, is published annually by the Scottish Church College Literary society. It was first published in 2015.

Activity clubs and extension activities

The NSS unitThe college runs the National Service Scheme programme under the University of Calcutta. Activities are carried on round the year and a special camp is held once a year. The NSS unit serves as a platform to connect students from the departments and motivate them towards community service alongside their learning process. Some of the activities include tree plantation programmes, voluntary blood donation camps, health and hygiene awareness programmes, and anti drug-abuse campaigns.

The Scottish Church College NSS unit has adopted the Dewanji Bagan slum area of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation, adjacent to the college play ground, and has focused its activities in that area. The NSS unit has 100 student volunteers, one programme officer, and 10 other teachers. The students of the unit are led by two student leaders, chosen every year. Every year 50 students participate in the NSS special camp. Apart from the NSS, nine faculty members of departments are associated with different NGOs in their individual capacities.

Four faculty members and three library staff are involved with social work at an informal level in their neighbourhood. The NSS Unit organised several environment/health/hygiene-related programmes in the college in collaboration with the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia and the college's department of Teacher Education.[17] The volunteers of the college NSS unit participated in North-East Youth Festival, held at Arunachal Pradesh in 2012 and NSS Mega Camp held at Assam in 2013. Some of them also took part in Rock Climbing and Adventure camp at Balasore, Odisha (India) and were awarded the title of "Basic Mountaineer".

The college received four awards from the University of Calcutta for its activities in NSS. Prof. U.N. Nandi became the Best Program Officer in 2009. Parag Chatterjee, a student of Computer Science and the NSS student leader (2011–2013), was awarded "Best Volunteer" by the university.[18] The college NSS unit received the "Best College" award in 2012, followed by Agnimeel Das, a student of Zoology receiving "Best Volunteer" in 2013. In 2018 Agnimeel Das has been appointed as Youth Officer in N.S.S. under Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Govt. of India through UPSC. He is the first former N.S.S. Volunteer of West Bengal joined as Youth Officer.

Activity clubs and societiesThe Scottish Church College has clubs and societies where students join and participate in intra-college or inter-college competitions.

• Debating Society

• Literary Society

• Nature Study and Photography Club

• Budding Painters' Club

• Western and Indian Music Club

• Dance and Drama Club

The Scottish Church College Annual Activity Day is organized by the college authorities annually, an event in which students from all departments gather to showcase their talents.

Sports and festivals

Annual sportsThe college conducts a sports day every December, in the college playground. Students compete in track and field events. The intra-college football and cricket tournaments are held during these two days. The students also participate in other inter-college athletic meets and sports meets throughout the year. The students of the college are regulars at the sports events organized by government colleges.

FestCaledonia is a four-days long cultural fest. Held annually, Caledonia is one of the largest and longest running festivals in Kolkata. It serves as a great attraction for students from different colleges. Caledonia invites other colleges from all over the city to participate in events like dancing, band performance, quizzes (the Chao Quiz being a major attraction) and a photography competition called Shutter Bugs. Caledonia does not confine itself to the four walls of the college campus, but goes out into the open by holding few of its on-stage events in Urquhart Square, outside the college. The fest is organized by the college authorities.

Students' unionThe students' union is the representative organization of the students. The main body of the students' union is formed by election of class representatives. The office-bearers are chosen by these members. The president and the general secretary of the students' union are the main representatives of the students, and they are also members of the College Senatus. It organizes cultural programmes like a freshers' welcome, Caledonia and the Annual Social. The students' union organizes annual blood donation camps, social service related activities and recreational activities for the students.

College ranking• The college is ranked fifth amongst Kolkata's top science colleges as per India Today (AC Nielsen-ORG Marg Survey of Colleges for 2006–07).

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2007: Rank 5 in Kolkata[19]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2008: Rank 3 in Kolkata[20]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2008: Rank 5 in Kolkata[21]

• India Today – Best Science college 2010: Rank 35 in India[22]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2010: Rank 5 in Kolkata[23]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2010: Rank 5 in Kolkata[24]

• India Today – Best Science college 2011: Rank 29 in India[25]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2011: Rank 2 in Kolkata[26]

• India Today – Best Arts college 2011: Rank 43 in India[27]

• India Today – Best Science college 2012: Rank 40 in India[28]

• India Today – Best Arts college 2012: Rank 41 in India[29]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2012: Rank 6 in Kolkata[30]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2012: Rank 5 in Kolkata[31]

• India Today – Best science college 2013: Rank 26 in India

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2013: Rank 8 in Kolkata[32]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2013: Rank 8 in Kolkata[33]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2014: Rank 7 in Kolkata[34]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2015: Rank 8 in Kolkata[35]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2015: Rank 7 in Kolkata[36]

• India Today – CAMPUS WISE RANKING: Best Arts college 2015: Rank 4 in Kolkata[37]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2016: Rank 5 in Kolkata[38]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2016: Rank 7 in Kolkata[39]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Science college 2017: Rank 8 in Kolkata[40]

• India Today – CITY WISE RANKING:Best Arts college 2017: Rank 6 in Kolkata[41]

AwardsThe Mother Teresa International Award was conferred on the college for its outstanding achievement and contribution in the field of education. It was adjudged the best college in 2014.

Mobile app for Scottish Church CollegeA mobile application was launched by the Scottish Church College on the Annual Day (13 March 2015). News and updates are notified through the application enabling students to keep up with the events and programmes of the college.

Alumni associationThe alumni association of the college is the Scottish Church College Former Students' Association. Its objective is to keep the former students in touch with each other, and maintain links with the college. The association organizes reunion meetings and social gatherings. Departments organize their reunion meetings either bi-annually or annually in the college campus. In West Bengal only Scottish Church College National Service Scheme Unit has their autonomous Alumni Association namely "Ten years and beyond". In 2017 first alumni meet of Ten Years and Beyond was organized.

Status and initiatives• Until 1953, administrative control over the college was exercised by the Foreign Mission Committee of the Church of Scotland. This was exercised by a local council consisting of representatives of the Church of Scotland and the United Church of Northern India. Later the Foreign Mission Committee of Church of Scotland relinquished its authority to the United Church of Northern India, and in 1970, the United Church of Northern India joined the Church of North India as a constituent body. This made the Church of North India the de facto and de jure successor (to the Church of Scotland) in running the administration of the college. As the college was founded on Christian (Protestant and Presbyterian) foundations, it derives its legal authority and status as a religious minority institution as defined by the scope of Article 30 of the Constitution of India.[4]

• On 27 September 1980, the Indian Postal Service released a commemorative stamp on the college.

• In 2003, the college buildings and premises underwent renovation, with the financial support of the alumni and well-wishers.[15][42]

• In 2004, the general section of the college was awarded grade 'A' after accreditation by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council.[43] The same grade was awarded upon reaccreditation in 2014.

• Since 2004, the college has been a member of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia and is a participant in that organization's Asian University Leadership Program.[4][44][45]

• In 2006, the University Grants Commission (India) accepted the recommendations of the University of Calcutta to regard the college as "College with Potential for Excellence".[4][46][47]

• In 2011, the Scottish Government instituted a Centre of Tagore Studies in Edinburgh's Napier University, to facilitate integrated research on Rabindranath Tagore's works and philosophy. In Calcutta, this scholarly initiative (with student exchange programs) was extended to the college, involving the departments of English, Bengali and philosophy.[17][48][49]

• The University Grants Commission sponsors the construction of the Quarto Sept Centennial Jubilee Building project of the college. The building plan has been approved by the Heritage Committee of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation for necessary approval. The construction of the new building has been completed with modern equipments and audio-visual system worth for having special lectures which can also be broadcast to other colleges through online.[50] The building was Inaugurated by the Members of college administrative body(College Rector Dr.J.Abraham and Principal alongside)

• Scottish Church College celebrated its 184th Foundation Day and its first Alexander Duff Memorial Lecture on 13 July 2013. The college welcomed Dr.S.C.Jamir, the Honorable Governor of Odisha and an alumnus of the college, who delivered the first Alexander Duff Memorial Lecture.

• In January 2014, the NAAC re-accredited the General Section of the college with Grade 'A' (meaning "Very Good") in January. The Teacher Education Section was reaccredited with Grade 'B' (meaning "Good").

• The college was awarded the status of "College with Potential for Excellence" for a third time, valid from April 2015 to March 2020.

Scottish Church College in popular culture

In fiction• Satyajit Ray's fictional scientist-cum-investigator Professor Shonku started his career as a professor of physics at the Scottish Church College.

• Satyajit Ray's fictional private investigator Feluda was a student of the Scottish Church College.

• Samaresh Majumdar's bestselling novel Kalbela, which explores Calcutta's culture, politics and society in the aftermath of the 1970s Naxalite movement, won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1984.[51] It featured the college as a backdrop in the storyline.

• Samaresh Majumdar's Animesh quartet, a series of four novels (Uttoradhikar, Kalbela and Kalpurush, and Mousholkal), revolves around the life and experiences of Animesh Mitra, an alumnus, who witnesses the tumultuous socio-political transformations in post-independence West Bengal.

In cinema• Kaalbela: Calcutta My Love, a 2009 Bengali film directed by Goutam Ghose on the events of the 1970s Naxalite movement, had scenes which were shot at the college.[52]

• Egaro: The Immortal Eleven was a 2011 sports film in Bengali directed by Arun Roy, that was based on the Mohun Bagan Athletic Club's victory over the East Yorkshire Regiment in the finals of the 1911 IFA Shield.[53] Three members of the winning team were students of the college. The film also showed the college as a background.[54]

• Natoker Moto was a 2015 biographical Bengali language film , which was roughly based on the life and tragic death of Keya Chakraborty, an alumna,[55] and English lecturer,[56] who subsequently became a prominent theatre personality. The character based on her is called Kheya in the film.

Notable alumni

Social reformers and religious leaders• Swami Vivekananda, proponent of Advaita Vedanta in the West and founder of the Ramakrishna Mission

• Rev. Lal Behari Dey, theologian of the Free Church of Scotland

• Brahmabandhav Upadhyay, theologian and preacher of New Dispensation Brahmoism, Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism

• Benoyendranath Sen, theologian of New Dispensation Brahmoism

• Sitanath Tattwabhushan, theologian and former president of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj[57]

• Krishna Kumar Mitra, former president of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj[58]

• Paramahansa Yogananda, proponent of Kriya Yoga in the West and founder of the Self-Realization Fellowship

• A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, proponent of Gaudiya Vaishnavism and founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness[59][60]

• Rev. Aurobindo Nath Mukherjee, first Indian to serve as the bishop of Calcutta and as the Metropolitan bishop of India within the Church of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon

• Swami Gambhirananda, former president of the Ramakrishna Mission[61]

• Mohanananda

Independence activists and politicians• Subhas Chandra Bose, former president of the Indian National Congress, founder president of the All India Forward Bloc, co-founder of the Indian National Army and head of state, Provisional Government of Free India

• Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala, first democratically elected prime minister of Nepal[62]

• Amarendranath Chatterjee, revolutionary associated with Anushilan Samiti, and Jugantar

• Syed Abul Mansur Habibullah, co-founder of the Bengal Provincial Krishak Sabha, and the Students Federation of India

• Saroj Dutta, veteran communist leader, co-founder of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) and the Naxalite movement.

• Ambica Charan Mazumdar, former president of the Indian National Congress

• Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee, former president of the All India Hindu Mahasabha

• Gopinath Bordoloi, prominent freedom fighter, first chief minister of Assam[63]

• Prafulla Chandra Sen, former chief minister of West Bengal

• Yangmasho Shaiza, former chief minister of Manipur

• Brington Buhai Lyngdoh, former chief minister of Meghalaya

• S.C. Marak, former chief minister of Meghalaya

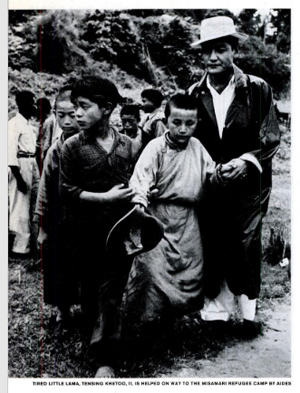

• S.C. Jamir, former chief minister of Nagaland, former governor of Maharashtra, Gujarat and Goa, and governor of Odisha

• Rishang Keishing, former chief minister of Manipur

• George Gilbert Swell, former deputy speaker of the Lok Sabha and former ambassador to Norway and Burma

• Birendra Narayan Chakraborty, former governor of Haryana

• Banwari Lal Joshi, former governor of Uttar Pradesh, Delhi,[64] Meghalaya[65] and Uttarakhand

• Ajit Kumar Panja, former minister of state for external affairs[66]

• Shawkat Ali Khan, a framer of the Constitution of Bangladesh[67]

Jurists• Sir Gooroodas Banerjee, former judge at the Calcutta High Court

• Sudhi Ranjan Das, former Chief Justice of India

• Amal Kumar Sarkar, former Chief Justice of India[68]

• Subimal Chandra Roy, former judge of the Supreme Court of India[69]

• Sambhunath Banerjee, former judge of the Calcutta High Court

• Amarendra Nath Sen, former chief justice of the Calcutta High Court, and former judge of the Supreme Court of India[70]

• Samarendra Chandra Deb, former chief justice of the Calcutta High Court

• Anil Kumar Sen, former chief justice of the Calcutta High Court

• Anandamoy Bhattacharjee, former chief justice of the Sikkim, Calcutta and the Bombay High Courts[71]

• Ganendra Narayan Ray, former chief justice of the Gujarat High Court, and former judge of the Supreme Court of India[72]

• Umesh Chandra Banerjee, former chief justice of the Andhra Pradesh High Court and former judge of the Supreme Court of India[73]

• Mukul Gopal Mukherjee, former chief justice of the Rajasthan High Court

• Shyamal Kumar Sen, former chief justice of the Allahabad High Court, and former governor of West Bengal

Scholars and academic administrators• Chandramukhi Basu, one of the first female graduates of the British Empire, and the first female head of an undergraduate college in South Asia (as principal of Bethune College, Calcutta)[4]

• Sir Gooroodas Banerjee, first Indian vice chancellor of the University of Calcutta

• Sir Brajendra Nath Seal, first chancellor of Visva-Bharati University, former vice chancellor of the University of Mysore[74]

• Sir Jnan Chandra Ghosh, formerly director of the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, founder-director of the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur and former vice chancellor of the University of Calcutta

• Tarak Nath Das, formerly professor of political science at Columbia University

• Sarat Chandra Roy, pioneering anthropologist, often regarded as the father of Indian ethnography, and as the first Indian anthropologist

• Biraja Sankar Guha, pioneering anthropologist, one of the first PhD recipients in anthropology in the world (Harvard University, 1924)[75] and founder-director of the Anthropological Survey of India[76]

• Nirmal Kumar Bose, eminent anthropologist and freedom fighter[77]

• Ramaprasad Chanda, anthropologist and archaeologist[78]

• Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri, formerly Carmichael Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, University of Calcutta

• Kalidas Nag, historian, author and parliamentarian

• Kaliprasanna Vidyaratna, Sanskrit scholar, author and academician

• Tapan Raychaudhuri, ad hominem professor of Indian history and civilization and emeritus fellow, St Antony's College, Oxford

• Rabindra Kumar Das Gupta, formerly Tagore professor of Bengali literature, University of Delhi, and former director of the National Library of India

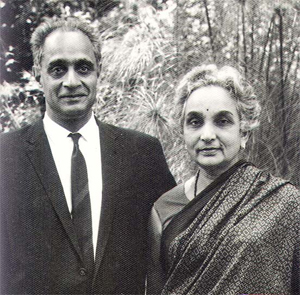

• Asima Chatterjee, first Indian woman to earn a doctorate in science, first female recipient of the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize for Science and Technology, and first female president of the Indian Science Congress[79]

• Animesh Chakravorty, recipient of the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize for Science and Technology in chemistry, formerly chair of the department of chemistry, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur

• Sambhunath Banerjee, Nirmal Kumar Sidhanta, Ramendra Kumar Podder, and Santosh Bhattacharyya, former vice chancellors of the University of Calcutta

• Nityananda Saha, former vice chancellor of the University of Kalyani

Performing arts, theater and cinema• Sisir Bhaduri, noted playwright[80]

• Pankaj Mullick, Bollywood and Bengali cinema music director and composer

• Birendra Krishna Bhadra, broadcaster, playwright, and theater director

• Suchitra Mitra, Rabindra Sangeet exponent

• Manna Dey, Bollywood film music exponent[81][82]

• Mrinal Sen, internationally acclaimed art film director and cultural commentator[83][84]

• Buddhadeb Dasgupta, noted parallel cinema director and poet[85]

• Tarun Majumdar, film director

• Utpalendu Chakrabarty, film director and thespian

• Mithun Chakraborty, Bollywood action hero and social activist

• Shyamanand Jalan, thespian and theatre director[86]

• Kaushik Sen, noted theatre personality, director of Swapnasandhani theatre group

• Silajit Majumder, singer and actor

• Badal Sircar, dramatist[87]

• Rudraprasad Sengupta, eminent theatre personality, director of Nandikar theatre group and cultural critic

• Partha Pratim Chowdhury, film director and playwright

• Manoj Mitra, dramatist[88]

• Madhav Sharma, actor, comedian, theater director[89]

• Pulak Bandyopadhyay, lyricist and composer

• Puja Banerjee , actress

Writers, poets and journalists• Dhan Gopal Mukerji, socio-cultural critic and first successful Indian man of letters in the United States of America; winner of Newbery Medal (1928)

• Nirad C. Chaudhuri, polymath, historian and commentator on culture, and Commander of the Order of the British Empire[90]

• Satyendranath Dutta, poet[91]

• Sudhindranath Dutta, author and poet[92][93]

• Ashok Kumar Sarkar, former editor of Desh literary magazine and editor-in-chief of the Anandabazar Patrika (1958–1983)

• Lakshminath Bezbaroa, writer, editor and social critic

• Parvati Prasad Baruwa, litterateur[94]

• Premendra Mitra, novelist, short story and science fiction writer, and film director

• Subhas Mukhopadhyay, poet[95]

• Samaresh Majumdar, novelist

• Sajanikanta Das, critic, poet and editor of Shanibarer Chithi

• Sanjib Chattopadhyay, journalist, author and critic

• Bani Basu, essayist, novelist, and poet[96][97][98]

• Kanhaiyalal Sethia, poet

• Kali Nath Roy, editor in chief of The Tribune magazine

• Farrukh Ahmed, poet, writer, activist of the Language Movement

• Derek O'Brien, quiz-master and author

• Bina Sarkar Ellias, founder-editor and publisher of International Gallerie, a global arts and ideas magazine[99]

• Mustafa Manwar, artist and media personality[100]

• Madhu Rye, playwright, novelist and short story writer

Administrators, industrialists and organization leaders• Binay Ranjan Sen, former director general of the Food and Agriculture Organization (1956–1967)

• Nitish Chandra Laharry, first Indian (and Asian) president of Rotary International (1962–63)

• Jagmohan Dalmiya, former president of the Board of Control for Cricket in India and the first Indian chairman of the International Cricket Council[101]

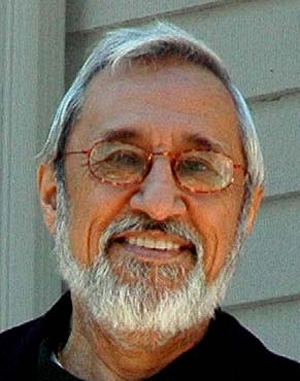

• Mani Lal Bhaumik, scientist (laser technology) turned entrepreneur, inventor of the excimer laser and author[102][103]

• Diptendu Pramanick, first secretary of the Eastern India Motion Pictures Association, and secretary of the Film Federation of India (1953–54)

• Evelyn Norah Shullai, pioneer of the Girl Guides Movement in India[104]

• Samson H. Chowdhury, industrialist

Sportspersons• Gourgopal Ghosh, football player for the Mohun Bagan club and mathematician[105]

• Dharma Bhakta Mathema, bodybuilder, political activist and anti-royalist martyr in the Kingdom of Nepal[106][107]

• Surya Shekhar Ganguly, chess grandmaster[108][109] and national champion[110]

• Sreerupa Bose, former member, India national women's cricket team

See also• Scottish Church Collegiate School, the twin institution of the college, also founded by Reverend Alexander Duff

References1. Saint Columba's main doorway

2. Basu, Pradip. The Question of Colonial Modernity and Scottish Church College in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008. p.35.

3. Matilal, Anup. The Scottish Church College: A Brief Discourse on the Origins of an Institution in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008. pp.19–20.

4. "Sen, Asit and John Abraham. Glimpses of college history, 2008 (1980). Retrieved on 2009-10-03"(PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

5. Pitlochry Church of Scotland's obituary of Alexander Duff Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

6. The missionary’s mission in Calcutta

7. Matilal, p. 17.

8. Basu, pp. 33–4.

9. Sardella, Ferdinando. Rise of Nondualism in Bengal in Modern Hindu Personalism: The History, Thought and Life of Bhaktisiddhanta. Oxford University Press, 2013. pp. 39–40.

10. Bandyopadhyay, Kausik. Games Ethic in Bengal: A Commentary on the sporting tradition of the Scottish Church College in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008. pp. 74–5.

11. A Tradition of Notable Firsts Archived 7 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

12. Master visionary

13. Basu, p. 35.

14. Manna, Mausumi, Women's Education through Co-Education: the Pioneering College in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008, page 107-116

15. Photo Gallery in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008. pp. 559–61.

16. Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources

17. Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and Extension

18.

http://www.scottishchurch.ac.in/NAAC/PDF-GEN/16.pdf19. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

20. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

21. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

22. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

23. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

24. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

25. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

26. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

27. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

28. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

29. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

30. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

31. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

32. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

33. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

34. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

35. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

36. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

37. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

38. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

39. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

40. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

41. "India Today". Specials.indiatoday.com.

42. Abraham, John. A Foreword in 175th Year Commemoration Volume. Scottish Church College, April 2008. p.4.

43. Abraham, p.6.

44. United Board Partner Institutions Archived 14 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

45. Abraham, p.8.

46. Star tag on six colleges

47. Half in, half out in college tag race

48. Tagore drew inspiration from Scottish bard for his poem – article in the Times of India

49. Glasgow tie-up for CU – article in the Calcutta Telegraph

50. The College Annual Day 2012–13

51. Sahitya Akademi Awards 1955–2007 Archived 16 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

52. Article in The Telegraph on the film Kaalbela

53. The death anniversary of Indian Football's first legend

54. Football scores at the box office in cricket-mad India

55. Some Alumni of Scottish Church College in 175th Year Commemoration Volume Scottish Church College, 2008, p. 589

56. Teaching Staff:English in 175th Year Commemoration Volume, Scottish Church College, 2008, p. 573

57. From the Brahmo Samaj website

58. Mohanta, Sambaru Chandra (2012). "Mitra, Krishna Kumar". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

59. Entertainment Homepage Archived 17 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

60. Ghosh, Monoranjan (2012). "International Society for Krishna Consciousness". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

61. Reflections around Swami Gambhirananda

62. Bisheshwor Prasad Koirala Archived 11 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

63. Gopinath Bordoloi

64. 'Big cities have big problems'

65. B L Joshi sworn-in as new Meghalaya Governor

66. Panja, Ajit Kumar

67. "Shawkat Ali passes away". The Daily Star. 1 July 2006.

68. Justice Amal Kumar Sarkar

69. Justice Subimal Chandra Roy

70. Justice Amarendra Nath Sen Archived 15 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

71. Justice Anandamoy Bhattacharjee

72. Hon'ble Mr. Justice G.N. Ray

73. Justice Umesh Chandra Banerjee Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

74. Roy, Pradip Kumar (2012). "Seal, Brajendra Nath". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

75. AnthroSource: Error

76. "Guha family wiki". Guha.pbwiki.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

77. Nirmal Kumar Bose – Scholar wanderer

78. Chowdhury, Saifuddin (2012). "Chanda, Ramaprasad". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

79. Chemistry alumni, Scottish Church College Archived 6 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

80. Mohanta, Sambaru Chandra (2012). "Bhaduri, Shishir Kumar". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

81. Padmabhusan Manna

82. "A Cultural Colossus". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

83. Chasing the Truth: The Films of Mrinal Sen

84. Sen, Mrinal

85. Merchant of Dreams

86. "Eminent theatre actor Shyamanand Jalan dead". The Times of India. 25 May 2010.

87. Mustard memories

88. Campus Buzz

89. A tale of two cities

90. Vita of Nirad Chaudhuri

91. Harun-or-Rashid, Md (2012). "Dutta, Satyendranath". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

92. Guha, Bimal (2012). "Dutta, Sudhindranath". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

93. Sudhindranath Dutta (1901–1960)

94. Parvati Prasad Baruva Archived 23 January 2013 at Archive.today

95. "People's poet of Bengal-Subhas Mukhopadhyay" Archived 8 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine By Dr Ashok K Choudhury

96. Bani Basu Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

97. Stranger than fiction

98. Meenakshi Mukherjee: Bani Basu's Novels Archived 24 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

99. Gallerie

100. Mustafa Monwar: A legend of our times Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

101. Jagmohan Dalmiya: Cricket's face of change

102. Code Name Success

103. Photo News

104. Adventure of knowledge – Evelyn Norah Shullai

105. Gourgopal Ghosh (1893–1940)

106. fitnessNEPAL.com (fitnessNEPAL/History) Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

107. "Encounter with a martyr’s daughter" By Sudha Shrestha

108. 'Unexpected' finish by Surya Sekhar

109. Ganguly, Surya Shekhar Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

110. Indian National Championship won by Surya Ganguly

External links• Official website