Part 1 of 2

A Promise Kept: Memoir of Tibetans in India [Excerpt]

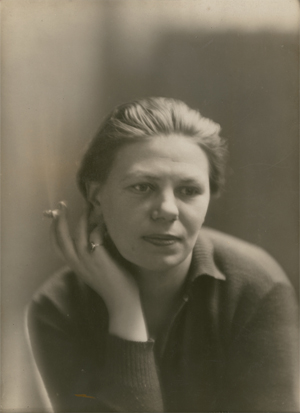

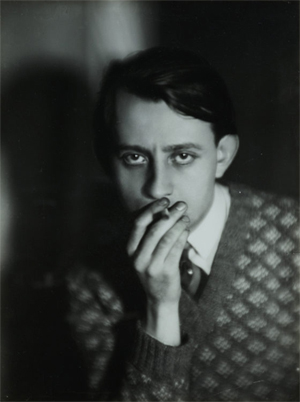

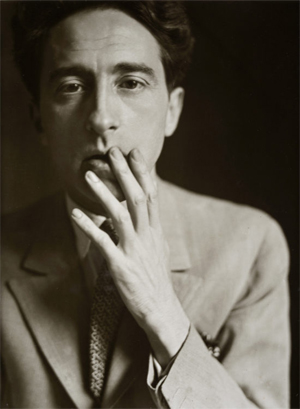

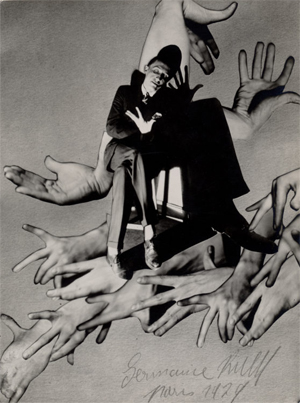

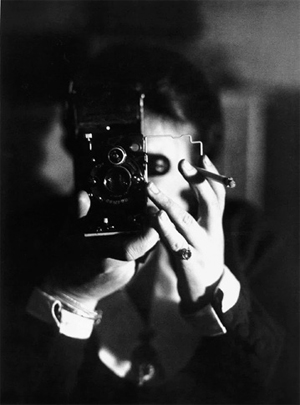

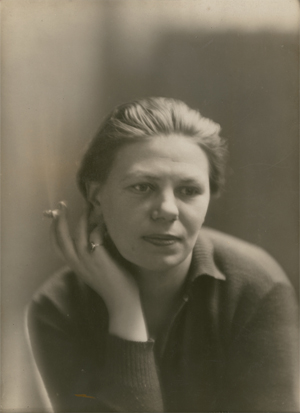

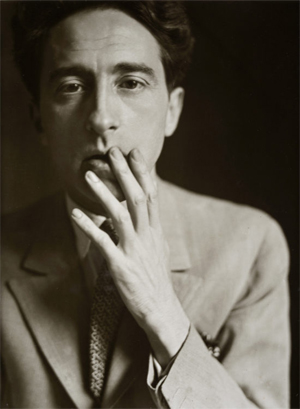

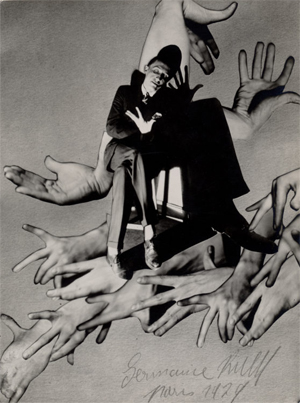

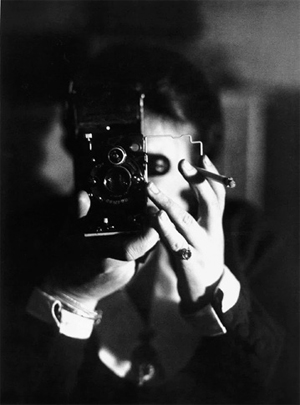

by Germaine Krull

© 2018 by Germaine Krull and Marilyn Ekdahl Ravicz, Ph.D.

Chapter 1

Yes, like everyone of my generation in Europe, I had heard and read about Tibet, the Roof of the World, where people lived high up in the mysterious Himalayan peaks. It was said that there were Lamas in Tibet who passed all the years of their lives in prayer and meditation. They were the keepers of their age-old Buddhist wisdom.

Strange tales were told about these holy men: that they would live for many hundred years; that they could walk without touching the ground; that they could appear simultaneously in different places; and that they could stop the thunder or command the rain to fall.

And then there was also the mysterious Dalai Lama -- the reincarnated Buddha -- who lived in the golden Potala, high up in Lhasa. where no one could reach him. He too was a Keeper of the world's Wisdom. Tales about his miraculous birth and reincarnations were told from time to time in books or popular magazines.

Those tales from my childhood were recounted and later confirmed in books about Tibet; however, none of them ever increased my real knowledge of that country. Yet, The Roof of the World remained in my mind as the holy site where Wisdom and Spirituality were kept alive.

Also like my countrymen and the world, I had heard about the invasion of Tibet by the Chinese Communists. I had even read about how the Tibetan people were fleeing their country. and even how the mysterious Dalai Lama left his golden Potala and took refuge in India too.

Newspapers had told us all about these events. However, our war-weary Europe was still so full of tragedies. and so full of refugees who were all so sad. that the tragedy of Tibet, an unknown for so many of us, disappeared quickly from the front pages of newspapers. And with that disappearance, once the subject was out of our minds, I -- like most others among us -- forgot about the Tibetans for the moment, and even until something happened to me.

It happened during one of those cold winter days in New Delhi, India, in 1962.

The Thai ambassador, whom I had met in Thailand where I still lived, invited me to attend a reception he was giving for a group of young Tibetan monks. These particular monks were said to have been identified as special young reincarnated Lamas of importance. I was told that this small group of Lamas was to be honored by a Thai reception. These young Lamas had been carefully identified and selected as tulkus by an English lady, Freda Bedi. They were selected from among Tibetan refugees working by the thousands in construction gangs along the roads of northern India.

The young Lama refugees being honored by the Thai Ambassador were to be enrolled in a school in Dalhousie. where they would learn English. Hindi. and how to deal with the ways of the Western world as special refugees. Their Buddhist studies would continue to be taught by selected Tibetan Lamas, in a manner consistent with their statuses as tulkus, and future adept-teachers, according to the established custom in Tibet.

The Thai ambassador wanted to entertain and honor the young Lamas, who were mostly ten years old to early teenagers. They were all refugees who had recently arrived in New Delhi. They had never seen countries outside of Tibet -- until they escaped, and were still viewing their country of exile with 'new eyes.' For this reason, the Ambassador had decided to show them movies of Thailand, and also give them Christmas presents.

As guests, we sat in the large reception room of the Thai Embassy in Delhi. This room had an elaborate marble floor inlaid with green and yellow designs, partly covered by beautiful carpets. The windows were closed and covered by drapes and curtains of Thai silk emblazoned in a golden flame design. The walls were high and topped by a dome-shaped ceiling that gave the room a sort of Byzantine air. Opposite the entrance, a life-size gold-framed portrait of the King of Thailand hung next to a similar framed portrait of his lovely Queen Sirikit. The corners of the room were occupied by heavily carved gold Thai vitrines, each of which held displays of Thai handicrafts and dolls. One wall of the room had been arranged so the projected film could be shown, and a row of chairs stood ready to receive the young Tibetan Lama guests.

As we sat around, I studied the Indian ladies. They wore gorgeous silk saris embroidered with gold and silver. I also saw that, since it was cool, they kept their sophisticated soft Kashmiri shawls wrapped around their shoulders. The European ladies mostly wore their fur coats. Only the Thai ladies, garbed in shiny Thai silk dresses with long skirts and a large front fold, seemed not to feel the cold. Their skirts touched the ground, and were topped with tightly fitted silk blouses that were closed from waist to neck by a row of round gold decorative buttons.

In the usual Asian way, the ladies were sitting together apart from the men. They were engaged in the usual gossip while drinking the usual martinis or fruit juices. On the other hand, the gentlemen remained standing, whiskey glasses in hand, and were attended constantly by white-gloved servants. from time to time, the ambassador's louder laughs hinted that the mood of the gentlemen was improving.

Suddenly the doors were opened and two young monks, no more than perhaps ten years of age, arrived. Perfectly calm, and in no way disturbed by the sophisticated surroundings or richly dressed ladies and gentlemen, they entered with folded hands and downcast eyes. They were followed by thirty or forty slightly older monks, all garbed in traditional red-burgundy robes. Without any commotion, they approached the Thai Ambassador in a group, and he greeted them with folded hands. After this greeting, they marched directly to their chairs and, with smiling faces, accepted the lemonade and cookies provided for them by the servants.

In no way did these young monks appear to be disturbed or to feel out of place. On the contrary, it was we who more or less seemed out of place. The very entrance of these young burgundy-clad monks had charged the atmosphere and made a difference. With their intelligent faces, bright dark eyes and calm acceptance of their new surroundings, something new had entered the reception room. Another world had suddenly opened (among and for us).

For me, that evening had initiated a strange sentiment of subtle potential involvement. I felt myself drawn to this group of monks, and somehow already realized that I might want to keep close to them. That evening ended, but not before I had made an appointment with Freda Bedi to visit the Tibetan refugee camp in Delhi on the following morning.

The following morning, a sophisticated white-clad chauffeur drove me to old Delhi in the Thai embassy car. On the way, we passed the famous Red Fort and followed the Ring Road until we finally reached a neighborhood of shabby huts. Many of these structures were made of mud mixed with straw into adobe. They had mostly palm roofs weighted down with stones to keep them from drifting away in the wind. Here, people were huddled in outdoor areas where they tried to warm themselves under the few rays of sunlight that could reach them. They were also trying in this way to avoid the cold winds that blew off the nearby river (the Yamuna River).

"Nothing good here," remarked the chauffeur repeatedly. We continued to drive until we reached the Buddhist Vihara where a large group of Tibetans had already gathered. Once stopped, I descended from the car and tried to make my way through the dense crowds of mostly Tibetan people.

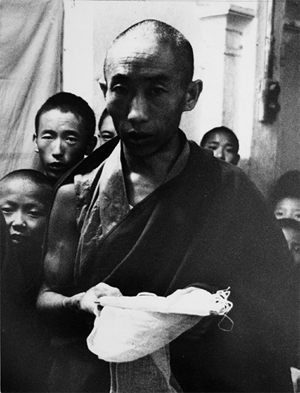

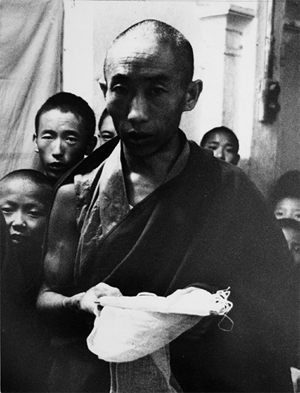

I had already seen multitudes of refugees in Europe, and had even visited a few concentration camps during and after World War II; however, somehow the refugees gathered here seemed especially tragic, although in a different way. Their faces bore expressions of extreme bewilderment. They seemed entirely lost and out of place. There were old and young women, children, and many old men. They sat hunched on the cold black earth. or huddled together on the cement stairs inside of the Vihara courtyard.

The Vihara itself comprised a spacious compound situated along one bank of the river from which an icy cold wind blew periodically. A kind of gallery or walled cloister surrounded the entire vihara compound, and many children were curled up in this protected area. The Tibetan men and women were dressed in similar darkish long robes, and their black hair was arranged in long plaits, which either hung down their backs or were coiled around their heads. Here and there the burgundy-red robes worn by the young lama refugees appeared. It was impossible for me to place my feet on the ground without trodding on an arm or a leg, and I didn't know where to direct my faltering steps in this sea of humans. where was Freda Bedi, and how could I find her?

In one far corner, I could see a commotion developing. Lorries loaded with bags of rice and wheat had pulled up, and these were immediately being off-loaded by Indian Officials. The workers tried valiantly to make themselves understood by the mob of gesticulating and screaming hungry Tibetans; however, it appeared their Hindi was not understood.

At last - in the midst of this confusion where I stood helpless and not knowing where to go - I caught Sight of one of the child Lamas I had met the previous night. He was emerging out of the crowd. Paying little attention to where I placed my feet now, I ran up to him, grasped his robe, and tried to make him understand that I was searching for Freda Bedi.

At first his face remained expressionless, but when he heard the name 'Mrs. Bedi,' his face came alive. I was immediately rewarded with a large smile and nod. After this, running like a small mouse, and weaving among the people without seeming to touch them, he led the way up and down several corridors. I followed him as best I could. People were huddled everywhere, and the entire compound seemed to be a sea composed of massed people in deep misery. At the end of this erratic search, I was virtually pushed into an untidy room where, in front of me, stood Freda Bedi. My little Lama disappeared as quickly as he had appeared, even before I could thank him.

"How sweet of you to come," Freda said. "It's an awful mess here today, but come and meet my daughter, Gulhima, and one of my two sons."

A charming Anglo-Indian girl looked up at me with shining eyes, and a very handsome youth standing nearby smiled. He resembled an Indian more closely than did the daughter.

"It is truly difficult here today," Freda continued, "because a brand new group of Tibetan refugees must be taken care of. They have only recently crossed our border from Sikkim, and apparently had been walking in the wintry cold for days and weeks before. They've walked through several snowstorms from their home areas in Tibet, and are now extremely exhausted and hungry

"Come and I'll show you around, Germaine Krull, but before that, let me give you the Tibetan blessing we learned to give to all our friends."

Freda took a tiny sculptured Buddha figure from a small shrine, touched it to her forehead first. She next touched it to the heads of her daughter and son, after which she touched it to my forehead too, ''This is the way we would give blessings to our friends in Tibet," she explained with a smile, "so why not do the same thing here?"

Next, we were shepherded along a corridor and entered a room that appeared to be a classroom. I saw some of the young Lamas from the previous evening seated here, along with an older Tibetan Lama. He was obviously serving as their teacher.

Freda explained the situation. "These young lamas are all reincarnations of high ranking spiritual previous Lamas in Tibet. With Nehru's consent and support, I have been helped to identify and pick them out from among the many refugees working along the roads in northern India. We intend to enroll them in a special school as soon as possible. They will need to learn what will help them understand about living in the Western world, since they will become special spiritual teachers in the future. We've also been able to identify and pick up many learned older Lamas too. They will now continue to teach the young Lamas their studies, which were interrupted by their collective flight from Tibet. We shall try to help them learn new subjects while maintaining the important spiritual aspects from their Tibetan heritage. In short, they will also learn to adapt to new ways of living as refugees in the Western world, but they will remain Tibetan tulkus as identified, and will teach and guide others in the future."

She turned and added, ''This is Lama Thuthop Tulku, Germaine. He is a reincarnated Lama who comes from a monastery high up in the mountains of Tibet. He is gifted, already picking up English quite well, and is even writing it correctly. This is his brother Chivang Tutku. They are both happy, because their parents were able to escape safely with them. They all escaped at the same time as part of a larger and therefore somewhat safer group."

I looked into the classroom and noticed my little Lama guide who assisted me today. He was sitting at the feet of his teacher, looking up at us and smiling.

Freda Bedi nodded to him and explained, "He is the reincarnation of the Abbot from one of the most important monasteries in Tibet. Now, in this incarnation, he will continue to be placed in charge of many thousand souls whom he will guide and teach when he is an adult.

"There are more young Lamas studying in another room. The whole group of these Lamas and their teachers will be leaving very soon for the north of India. They will settle for the present in Dalhousie, on the edge of the Himalayan lower mountain ranges. There, we have been given a very large house which will serve as our first Lama Home-school. To establish this school, we shall assemble as many special young tulku Lamas as we are able to identify. We also hope to find volunteers from various other countries who will come to India and help us by volunteering to teach them English."

Freda Bedi continued to explain how different groups of Tibetan Friendship Societies were being created around the world, especially in the neutral countries of Europe. She ended with: "I hope, Germaine, that you will come and visit us in Dalhousie. I look forward to showing you our school. It will be the result of two plus years of personal planning and effort."

We were shepherded back down the same corridors, and entered the sea of humans gathered outside around the Vihara. We continued making our way along the riverbank where bunches of Tibetan women were huddled or squatting on the ground with their babies. They were trying to feed them in spite of the cold wind. One of the older English-speaking Lamas had accompanied us, and he translated the many requests for aid from Freda Bedi being made by the Tibetan refugee women.

"You see," he explained, "some of these babies were born along the way from Tibet, and a few were actually born here. This tiny one was born yesterday morning," he pointed, "and we still don't have enough milk for it. The Indians themselves often find it difficult to get milk for their own children, although cows are roaming around everywhere. We still have some powdered milk that friends have given us, but it is never enough for our growing needs."

In spite of their suffering, the women looked at us with warm smiles, apparently relieved to see kind and interested people. At least there was no more wading through snowstorms or rains, and no more fear of Chinese soldiers. At least those dramas were behind them now.

I followed Freda through the camp, and saw many old men in ragged robes twirling their prayer wheels. others were chanting prayers. Some were holding their malas (rosaries) in their left hands, while twirling their prayer wheels with their right hands. The old men had wrinkled faces and faraway expressions on their faces under their plaited hair. They wore ragged clothes, but never stopped twirling their prayer wheels or chanting prayers, as they huddled in small groups. I would see similar sights often in the future.

We noticed that some of the women had already started what would become a kind of national refugee-occupation: knitting wool sweaters. As we circled and approached the front of the Vihara, the crowd became even more densely packed. Questions rose softly or in shouts, and were put to Freda from all sides. She pointed out persons who had suffered frozen toes, legs, and hands, as well as others who still had large open unattended wounds. I recall seeing one man whose face appeared to be half eaten-up by something.

"A leper, perhaps?" I asked Freda.

"Yes, possibly." she answered with a sigh. "Or perhaps some other undiagnosed disease that we might not have seen before. Tibetans were isolated a long time, and have little or no resistance to fight against certain physical problems - like chronic infections or tuberculosis."

The Indian officials had by then discharged all their bags of rice and wheat. They also assured Freda that a team of doctors would arrive later that day to attend those who needed additional care among already treated refugees, as well as to help the newly arrived patients.

I left the refugee camp and Vihara about noon that day; however, I also promised Freda Bedi that one day I would visit her in Dalhousie. This is a promise I knew I would certainly keep, even if in the somewhat distant future.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Part 2 of 2

Chapter 2

After this visit with Freda, I planned to return to Europe for several months. I had only planned to stop briefly in Delhi on my way to Europe from Thailand, where I still lived and worked. I sometimes returned to Europe via Delhi, since good direct transport to Europe is still scarce in Thailand. Now I had already stayed more time here than planned, and was anxious to leave as previously arranged.

I had again returned to Thailand, but not to work for too long, and eventually traveled on to India. On this return to India [1965?], I was accompanied by a young Siamese companion: a girl named Leck. She was a friend who had often worked for me while I lived in Bangkok, during my twenty or so years of living and working in Thailand, before I decided to retire in 1966.

During this trip to India, I wanted to avoid the usual manner of tourist travels. During previous visits to India,. I had been in the controlling orbit of tourist organizations. I stayed only in the recommended big tourist hotels, and used only tourist guides. Even my visits to the South of India had been in privately hired cars with drivers and guides. During this trip, I was determined to escape the same tourism orbit. Therefore, somewhat courageously I purchased two seats on the Kashmir Express -- first class sleeper -- all the way to Pathankot, the terminus of the railway. From there, a local bus or shared taxi would carry us on to Dalhousie, where I hoped to visit with Freda Bedi. I wanted to see how her work was progressing with the Tibetan tulkus whom I had met at the Thai reception in Delhi (in the winter, near the end of 1962.

The Kashmir Express was actually quite a comfortable train. Clean bedding was provided for first class passengers, and the four private compartment ventilator fans all worked properly. According to the schedule, having left Delhi about midnight, we were to arrive in Pathankot by 8:00 AM., the next morning. I had a sound sleep that night, but when I awakened my companion Leck said, "You know, Germaine, it seems we are almost about eight hours late."

"What do you mean eight hours late? That's impossible!"

"But I think that is what the porter man said."

I soon found that Leck's statement was unfortunately true. I learned that we were indeed nearly eight hours late. Apparently our train had run into another train on the same rail track, but going the opposite direction. Thus, a wait of several hours to correct this flaw was inevitable. Now we were very late. Soon enough, it started to become very hot inside our compartment. An Indian gentleman, a neighbor in the next compartment, had passed our door several times. He appeared especially interested in my little Thai companion, and therefore proved very helpful to us about securing our breakfast.

I complained to this gentleman that I was worried about our schedule. There was only one daily bus to Dalhousie, and now it would have left long before our late arrival. I asked, "Is it possible to hire a taxi in Pathankot?"

But now the Indian gentleman was of little help. It appeared that he was a high official in the railway administration, so he tried to convince me to return to Delhi later by the same train. As an alternative, he also suggested that we could travel on to Simla, Mussoorie, or some other 'more modern' hill station. Indeed, he insisted that Dalhousie was not interesting to visit for any reason, let alone for tourist activities.

Finally, by somewhat after noon we arrived in Pathankot. There were hundreds of people crowding the quay, and screaming porters came barging into our compartment. This time, I think we would have been lost without our Indian gentleman's help. With a few words, he instructed one porter what to do. He placed our luggage on the head of that porter, and instructed him and us to follow him out of our compartment, and to continue on to the train station to wait.

We followed our helper, and were guided into the station waiting room. We found it to be clean, furnished appropriately, and even air-conditioned. Our luggage was stashed in a corner and waiters - in uniforms that had once been clean - served us a good breakfast of tea, toast and eggs.

During the meal, our Indian gentleman once more suggested that we board the same train and return to Delhi. However, I insisted that I was intent on traveling on to Dalhousie to visit a good friend. I also asked him if there was somebody responsible with whom I might talk about this arrangement in English.

"None of these workers speaks English, only the Station Master. But it appears that today he is absent for an all-day meeting."

"Well then, is there a taxi I could hire to take us to Dalhousie? Or another bus that we could take tomorrow morning?"

"I can offer you my room here, which has an adjoining bed and bathroom. And I'll also see what I can do for you. I'll be in a meeting myself meanwhile, but I'll return later today. I assure you again that my compartment on the train will be vacant, and it's at your disposal if you change your mind and decide to return to Delhi." He was indeed a thoughtful and helpful man, but we didn't want to return to Delhi without seeing Freda. It was also becoming too hot on the plains of India, and would be cooler in Dalhousie anyway.

After he left, we went out on the platform, which was by that time truly 'burning hot.' I started to search for someone who could speak English. At last, in one of the booking offices, I found a clerk who also informed me that the Station Master was out for the day at a meeting. However, he then added that we should stay in the station room provided for us as travelers, and explained that our needs would be met by the staff, while we waited here in Pathankot overnight.

Time passed slowly that day. We were trapped in Pathankot, and it was too hot to go outside. Fortunately by late afternoon, I was able to verify that we indeed had a reserved room with bath. It was on the first floor of the train station, so we then moved our things into that room for a sound overnight sleep later.

By late afternoon, when the Indian gentleman returned, he was quite disappointed that we weren't prepared to return to Delhi. Although he suggested he had made arrangements for the bus, in fact he had not. Also by late afternoon, it was much cooler. I looked around the station again, and realized that fascinating scenes lay all around and in front of us below.

Our balcony overlooked the train platform, so we watched the people hurrying about below. We saw there was a train about to embark for somewhere, and hundreds of people were boarding it. They were mostly carrying their bedding on their heads. Personal bedding consists of a blanket, sheets and whatever is needed for the night, all rolled up in a canvas cover.

We saw men, women, children and soldiers milling about. The latter had packs on their backs and canteens dangling from their belts. We also noticed that some of the men, oddly enough, boarded the train through the open windows! The whole station was a scene with much crowding, a multitude of shouts and screams, plus other unknown noises. There were also itinerant merchants selling all kinds of snack foods. These ranged from fried bananas to boiled eggs, along with a variety of mysterious dishes wrapped in banana leaves.

Along with the noises of the people was the added ruckus of hundreds of screeching parrots, which had settled like a colorful cloud in two big trees adjacent to the balcony. It was amazing how these birds found space to perch among the thick foliage, while screaming at each other and flapping their wings to fight for places. All this coming-and-going continued until the train below finally departed.

We decided we should find the place from which the bus was scheduled to leave, as well as a more exact time of its departure for Dalhousie. To accomplish our search we decided to leave the balcony and go for a walk in the streets below.

I had never before seen so many different but quite equally dirty shops. We couldn't learn exactly what it was they were all selling, but they must have all been selling something. The shops lined the streets in side-by-side rows. The streets were also packed with various kinds of vehicles: big military lorries; small hand-carts loaded with grass; and other larger carts loaded with what appeared to be home furnishings. Many of them, except the military lorries, were pulled by hungry-appearing horses. There were also bullock carts loaded with timber, and many tongas. These vehicles were all jam-packed with women, men and children.

There was also an interspersed sea of humans peddling their bicycles. Some used their handlebars as second passenger seats, while also carrying loads on their back racks. All these people were going or coming to and from other places. I wondered how we were ever going to find the bus stand in all this confusion. We looked around rather desperately now.

Every time I saw an army officer, I tried in English to ask directions. Finally, we arrived at a dusty and dirty location that we were told was the 'bus terminus for Dalhousie.' We were also told that the bus would leave at 4:00 AM. Since there was nobody from whom to buy tickets or take reservations, we were simply told to be at the terminal early the next morning, and we would 'surely be able to find two seats.'

I wasn't satisfied with the answers we were given, and began to wonder if we would ever reach this mysterious Dalhousie. While we managed to return to the safety of our room in the station, our next problem was to find someone who would awaken us at three in the morning, and also help us carry our luggage to the bus terminal we had found.

That evening, a rather surprisingly elaborate dinner was served to us in our room. I made one last attempt to see the Station Master, and was finally able to contact the Assistant Station Master. He informed me the Station Master was still absent at his meeting; however, he seemed to be a very kind Indian man, and told us not to worry. The night watchman would awaken us on time, and would also help us with our portage problem. He also insisted he was certain we could find seats in the very early morning bus to Dalhousie.

That night passed quite well, except for the noises from nearby water pipes, which every now and then broke into piping screams. At three in the morning, the night watchman, who was obedient and dutiful, awakened both of us. We dressed in the dark, since the electricity had failed, and we had no flashlights with us. We managed to load our luggage onto the head of one porter, and ventured into the pitch-dark streets below. Our only guide was the glowing tip of the cigarette in our porter's mouth, so we dutifully followed it.

I don't know exactly how far we walked, but in the end our porter put down our luggage and squatted beside it. There was no bus in sight. Inside the nearby hut - which I saw served as part of the office - we could see several people stretched out on the floor. They were fast asleep, but soon started to stir. Gradually life erupted in and outside the hut. There was nothing to do but wait. Dawn came with its dim light, and things slowly took shape. At last, an old rattling bus arrived. It was powered by an infernally noisy engine. Once parked, all the people immediately rushed toward the bus. It was a wonder that both of us managed to grab window seats. Our porter stowed our luggage under our feet, and we gratefully settled down for the next part of our fateful trip to Dalhousie.

Our bus sported the rather pompous name: 'Kashmir Tiger.' Our driver was a lean and lanky chap. He had long bony arms, long legs, and a high forehead partly covered by a turban, which is called a 'pugri' in its Indian name. He also had a long hooked nose, twin dark eyes and a large mouth partly covered by a reddish droopy moustache. He wore khaki trousers with black patches, and a kind of dark khaki vest and coat. Worn proudly on one shoulder was pinned a small metal badge stating: 'Kashmir Tiger.' He was as long and rattling as his bus, and managed, by shouting and pushing people around, to make some kind of order in the bus. At last - off we went!

We took off with tremendous speed, leaving behind clouds of scattered dusty smoke. Very soon the plains slowly disappeared and we started to climb. The first portion of the road was quite good, and the curves were not too bad. Our Kashmir Tiger took us along all of them, puffing and screaming loudly. Eventually we stopped at a roadside teashop for a break. The shop had been part of a former British rest-house, and we were grateful for the tea and toast served to us there. After that, we climbed back into the bus, creeping over legs, hands, and luggage to reach our seats.

From that point onward, our road became a dreary one-lane passageway. For the next few hours, our ride was on a narrow mountain road, full of treacherous curves and sharp turns. This nightmarish part of the journey remains forever fresh in my mind. As the bus rattled along, it seemed at every curve we might scrape or bump against the mountain on one side, or find ourselves hanging in the air on the other side. I'm still not sure how we managed not to bump into the mountain of rocks in front, or fall over the edge of a cliff in our back during that wild ride!

Inside the bus, passengers were thrown from side to side, no matter how hard we tried to cling to our seats or the windowsills. The bus soon became a terrible mess: water spilled on the floor; luggage fell or slid everywhere; women moaned; children cried; and many leaned out of the windows to be sick. The only one who seemed to enjoy the ride and the passengers' discomfort was the driver. The worse the situation became in the bus, the happier he seemed to be as we throttled along.

I don't know what might have happened if our way had not been finally blocked by a military convoy. Our driver actually overtook one of the convoy trucks, and almost drove it over the edge and off the cliff. Obviously this contretemps forced the military convoy to stop. The convoy Commander, who was by that time quite angry, ordered our bus driver to: 'Fall in line behind my trucks and stay there!' This happenstance event forced our slow-down, and gave the passengers time to recover a little. Finally, after these few hours that felt much longer, we arrived in Dalhousie, a hill station situated at roughly near the seven thousand foot altitude level.

As porters crowded around to grab our luggage upon our arrival, my first impression of Dalhousie was dual: agreeable fresh air and fascinating scenery; and generally confusing with respect to town layout. We immediately saw two hotels in front of us. One was named 'Snow View,' and the other was called 'Mountain View.' To reach both we had to climb up numerous steps. By now, steep hills seemed to encircle us on all sides. Somehow we landed in Snow View, and immediately ate the very good breakfasts served to us in the hotel restaurant.

The view of the encircling mountains was absolutely beautiful. There were no snow-capped peaks visible at the present time, since the mountains were covered by a summery green sheen. A forest of tall pine and cedar trees covered most of the adjacent hilly slopes, and the landscape was entirely composed of a series of hilly ups and downs. Moreover, it actually appeared as if the entire scene was creeping steadily upward, which I later learned was generally true.

I begin to wonder how we would ever be able to find the Tibetan Lama School, since even the owner of the hotel spoke very little English. He seemed neither to know nor had he ever heard of any Tibetan Lama School when first asked. It appeared, as he noted, there were indeed several schools in the area, but how were we going to find out their exact names and where they were situated?

Then I asked, "Have you ever heard of an English lady named Freda Bedi who arrived here with many young Tibetan lamas?"

"No, never!"

I remembered another referral word, so I next asked: "Have you ever heard of a place called the 'Tibetan Kailash?'" The hotel man answered this query quickly in the affirmative. The word 'kailash' ticked his memory as an unusual school referred to in Dalhousie.

"Oh, yes," came his immediate answer. "It is way higher up, near the base of the mountains. There you will see that it's one really big house, now used for teaching young students. Actually, the Kailash might even have a telephone!"

The Kailash did indeed have a telephone, and I was able to speak directly with Freda Bedi. She informed us that she would send a Tibetan youth down to meet us at our hotel. She also added, "Since it is quite high up, it might be necessary to ride a horse instead of trying to walk all the way in this altitude."

We waited for some time, but finally a young Tibetan boy arrived. Surprisingly, he already spoke quite good English. Our luggage was loaded on the shoulders of a young Indian porter, and we set out for our hike up to the Kailash.

I must admit that I was not very courageous by now. My many years of living on the plains made it difficult now for me to climb.

In short, after a little while, I agreed to ride the horse that accompanied us. However, because I hadn't ridden a horse since early childhood, the steep climb onward was as hard for the horse as it was for me. Yet, the higher we climbed, the more beautiful the scenery became. We were surrounded by a mountain forest of tall green trees, while being fully encased in air that was extremely fresh and clean.

Near the end of this journey, we reached a kind of circular flat roadway where our party rested for a while. From this point on, a more level road led in a meander up to the Kailash, which I could see ahead and still above us. I decided to climb down from my horse. However. since I was unable to regain full use of my legs for some minutes, I must have made a grotesque sight staggering around! My girl Leck and the Tibetan youth burst into laughter. Indeed, it took quite a while for me to regain full and confident use of my quavering legs.

We finally reached the big wooden house. We saw that it had a large double front door over which was posted a large sign: 'Kailash Young Lama School.'

We continued down a narrow path and saw that this large house actually resembled a Swiss Chalet with its deeply pitched roof; however, at the same time it had the curious air of a small Indian castle with one small soaring tower. We next mounted more steps to a banked terrace where patches of colorful flowers surrounded us. Our Tibetan guide had already run up the stairway ahead of us, and disappeared into the house.

I was quite weary, and found it difficult to recover my breath in the higher altitude. I stopped in front of the house to view the scenery. It was unique, and appeared to consist of range after range of mountains, each succeeding the previous one in an apparently endless regression of higher peaks. Next to the Kailash were two tall cedar trees that spread their branches over the house like protecting arms or wings. Along the side, clusters of tall pine trees stood like watch towers. I was lost in dreams, but soon heard Freda Bedi's voice calling from somewhere in the house.

"Come in, Germaine, dear! Come in, dear Germaine! I'm so glad you were able at last to come for a visit."

Somehow I continued on, and stumbled up a narrow staircase into the protecting arms of Freda. I looked around and saw we were in a small entry room. On a low bench were several piles of mail. Obviously Freda was trying to catch up on her correspondence. Pushing aside a few bundles and parcels, I sat down heavily on the bench. I tried to recover my panting breath bit by bit.

As soon as we were truly settled in a room nearby, Tibetan servants hurried in to serve us tea and a variety of snacks. Freda began to tell us about the school for which she had worked so hard for more than two years.

"The Young Lama School is the first of its kind in India. There are now fifty young Lama Tulku students here, along with some other monks who enrolled to learn English. If they become better-educated, they will help with teaching others the Dharma. We soon expect many more will be coming, so we shall definitely need more teachers. The young Lamas continue their Dharma studies here under Tibetan Lamas, but also study English reading, writing and speaking every day. They are the best assurance that the Dharma and Sangha will endure into the future; therefore, His Holiness the Dalai Lama is in favor of this school. He also helped planning for it soon after his escape to freedom."

"We have set up the educational program here quite well," Freda said and then noted: "There are a number of young volunteers who have come from all parts of Europe and America to help us with the English teaching part."

At this moment, the door opened and Thuthop Tulku entered. Freda nodded at him and continued: "He has become very good in English, and is now able to help me with our voluminous correspondence. You see, Germaine, it's increasingly the case that we have Tibetan friendship groups forming all over the world. They help by volunteering, as well as by sending us clothing and sometimes some money too. Their gifts help to sustain us here."

We continued to converse for a few hours, interrupted only by servants who occasionally refilled our teacups. By now, and after this conversational rest, I had finally recovered my strength in spite of the altitude.

Freda Bedi added: "You can stay in the Guest House, which is just next door, Germaine. You'll have an Indian servant there who will furnish you with hot water for bathing and your tea. I'll send over Tibetan food for lunch or dinner, and you and Leck can come here anytime you want to visit. Rest yourself and stay as long as you wish in Dalhousie."

off we went again on that circular walkway. It appeared that Freda Bedi's 'next door' meant a walk of more than half an hour for Leck and me, mostly among the pines and cedars.

At last, the young Tibetan monk, carrying our bedrolls and baggage, pointed up the mountain to a small white house. It resembled an eagle's nest. This was Freda's 'next door' Guest House. As we continued to scramble and climb up this final steeper and rockier path, even my little Siamese girl, Leck, had to use her hands to grasp and hold on to the grassy edges to manage making it up the path. Frankly, I don't know how I managed to get up to the house -- by puffing like a steam engine, I guess.

Once we arrived and entered the house, I immediately felt its unique enchantment. A large covered verandah circled the house and overlooked the mountains and valley below. There, well below us, a river flowed like a silvery curving ribbon. Tall trees surrounded the little house like watchful sentinels, and patches of colorful wildflowers bloomed everywhere.

The first floor of the house consisted of one large room attached to a bathroom with running water. This room was furnished with two Indian beds covered with Tibetan rugs, and the remaining furniture included two overstuffed chairs. A large window with glass panes, partly replaced by plywood panels, overlooked the scenery below. That was our bedroom. Outside, the verandah was furnished with a table, two hard chairs and one easy chair.

Next to our big room I saw a smaller room. Our Tibetan helper told us that a young man named Peter sometimes stays in this room. He also said that the kitchen was situated on a lower level, that is to say, downstairs from our big main living and sleeping room.

We quickly installed ourselves in our room, and Leck decided to go down and inspect the kitchen. When she returned, she shuddered at what she had seen. Half in Thai and half in English, she reported her results. She had tried to communicate with the Indian woman there, hoping she would understand the need to clean up the place; however, she wasn't hopeful.

The first night passed without event. I slept from early evening until the next morning in one stretch. Early the next morning, I stepped out onto our verandah and looked down toward the valley below. The sight was breathtaking. The next impressive element was the many monkeys playing in the trees adjacent to the house. When standing upright, they were nearly the size of a man!

Leck soon came into our room almost screaming: "The monkeys are so big that I'm afraid of them."

Our young Tibetan boy, who was still present as a helper, insisted the monkeys were harmless and would never enter the house. Leck wondered about this, but decided instead to focus on washing the kitchen before it was necessary to use it.

Suddenly we heard sounds emanating from the room where Peter was supposedly staying ·sometimes.' I realized we had completely forgotten that he was 'sometimes' here, until we heard the chanting. It became louder and louder, but it was still unintelligible. Later we learned Peter chanted in Tibetan.

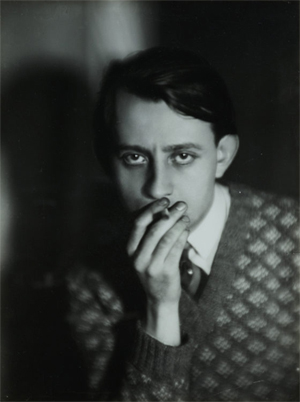

Hours later, when Peter came out of his room, we saw he was a tallish, rather pale young American. Peter, who seemed to be about twenty years old, was dressed in a pair of colorless trousers and a white shirt, open at the neck. A scarlet silk cape with a thick cotton lining hung over his shoulders... His feet were shod in worn Indian sandals. "Good morning," he said, "I hope I haven't disturbed you with my morning chanting."

"Oh, no," I shrugged. "I guessed that you would be Peter. Did you have your breakfast? You look so cold."

"No, thanks, but I will have a cup of tea. Actually I'm not cold. This cape, which is not mine but borrowed, is actually very warm."

Peter seemed generally quite absentminded - mostly as if absorbed in some mental questions or exercises of his own most of the time. I asked, "Peter, how long are you going to stay here? And are you going to be teaching the young lamas?"

"Not exactly. That is, I'm helping Mrs. Bedi with some translations, and may stay here for a while, but I really don't know anything for sure yet. You see - I just returned last night from the plains - and now I planned to go down to the Kailash to talk with Freda. Do you have any messages?" He glanced around at us with this question.

"Please tell Freda that I won't be coming to see her today. I wouldn't be able to make it up the hill once I got down after yesterday. I'm still tired from that hike, and need to get more accustomed to the altitude a bit."

Our daily routine took shape and continued in the same pattern for about a week or so. After breakfast, Leck would try to explain to our Tibetan helper that she should try to buy some fresh fruit and vegetables in the market at Dalhousie. Although it was summer, fresh food supplies were not easy to obtain. There were almost no vegetables in the market except some cabbage, poor potatoes and few dessicated carrots. Local gardens were scarce. After trying to buy a chicken that looked more like a sparrow, plus some really poor bony-looking mutton, we gave up pretty much. Fortunately we still had tea, Tibetan noodles, some biscuits and good jam. With these items we were more or less satisfied daily. Occasionally our Indian woman helper would bring us plates of wild raspberries, which were ripening everywhere on the mountain slopes. They were truly delicious.

At this point, Leck was busy trying to help solve our material problems, but I continued to be tired. It seemed a bad cold had taken hold of me, and I felt worse each day. Now the days seemed to drag by. Then one day I felt somewhat better, so we finally ventured down to the Kailash. We hoped to visit with the little Lamas, one by one if possible.

Thuthop Tulku accompanied us around the Kailash, and tried to explain everything for us while I took pictures. We saw there was one big room reserved for the volunteers to work in. We met a couple from Canada there. She was a tall blonde girl, and her companion was a broad-shouldered young man with a long black beard. They both seemed quite unconscious about the state of their clothes, and were both dressed mostly in rags. The young woman was barefoot, and the young man wore a pair of Indian sandals held together with string. Nevertheless, they were quite jolly, and full of fun and laughter. They seemed to be dedicated teachers for the young Lamas, who seemed to like them very much too.

I saw Peter sitting in one corner furiously typing on an ancient typewriter. In another corner, an Australian boy in Tibetan clothing was sitting on the floor. He was looking through Tibetan manuscripts and books, page by page. What an odd international collection had gathered here in the mountains of Dalhousie, India!

That was the first occasion that I actually saw and handled Tibetan books. I saw they consisted of long, loose leaves a little more than a foot in length and about four to five inches wide. Each page was hand-written with script on both sides, and the leaves were piled together into ordered groups about four to five inches thick as a 'book.' Each bunch was wrapped carefully in pieces of colored silk and tied with string.

We learned there were several volunteers working in the Kailash. many of whom were not in the volunteer room at the same time. This is because they were teaching the little Lamas in separate classrooms.

We also met the newly appointed Abbot of the Kailash on that day. He was a young and handsome Lama who spoke quite good English. Freda later told us that he was one of their most important tulku reincarnations. He had luckily left Tibet before the Chinese invasion, and was now devoted to working with the refugees. He had lived in Sikkim for several years, and learned considerable English while in residence there. I also saw several very old Lamas with deeply wrinkled faces, and sincerely hoped to have enough time to photograph some or all of them before leaving Dalhousie.

We later lunched with Freda, and I admitted to her that I was not feeling at all well. I even asked, "Is it possible to find a medical doctor around here?"

"I'm afraid, Germaine, that the doctors around here are not very good. And I'm sure there is no appropriate cold medicine available in Dalhousie. It would be better if you just stayed at home and rested. I'll send your food up to you. Use your own medicine if you have any, and just rest a few days. I realize this altitude and climate are difficult to become accustomed to."

We stayed on at the Kailash that afternoon. There was a special religious ceremony scheduled, and I wanted to take pictures of the monks gathered together.

The ceremony took place in the shrine room, which was a long relatively undecorated room in the main house. On the shrine altar, I noticed a newly painted statue of Buddha, wrapped in several layers of white prayer scarves in the typical Tibetan manner. A row of silver offering bowls was placed in front of the Buddha statue, and a bunch of colorful paper flowers had been heaped nearby. Next to the shrine altar, a large electric bulb shed its light into the far corners of the entire assembly room. I had been told that lights placed over shrines help to attract the attention of the spirits, along with the scents of food and other altar offerings, such as incense.

A row of torma cakes was also placed near the front of the altar. As usual, these torma cakes were made by mixing butter and barley flour into a dough that was sculptured into the usual round and pointed cone-like forms. These were quite simple, since none was decorated or painted with designs. I had learned that tormas were meant to serve as food offerings to the Buddha and/or particular spiritual embodiments for whom the altar was dedicated. The shrine altar also held a row of small bowls that contained the usual offerings: water, barley and rice. A row of butter lamps burned along the very edge, in front of all the other offerings.

Along the wall in back of the shrine altar hung three large thankas, as well as the usual large photograph of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Two parallel rows of chanting monks sat on small Tibetan carpets placed in front of the altar. In all, there were about forty or fifty little Lamas being led in prayer by the Abbot, who sat elevated in the middle of the room in front of the shrine altar. Nearly all of the volunteers entered and participated by joining in as well as they were able.

I felt as if I were in another world where time did not count. It was nearly dark by the time we came out. While on our way up to our eagle's nest house, we were caught in a heavy and sudden rainstorm!

"Oh my, Leck, just look," I complained, "how far we truly are from Western civilization's promises! My trench coat, which was supposed to be waterproof, has absorbed water like a sponge."

Drenched, cold and shivering, we arrived at our little perch-house again. It seemed as if that night might finally be the end of me! My cold now settled inside me in earnest, and it lasted for more than five days without improvement.

On the fifth day, when I was sitting on the verandah wrapped in my fur coat and all the blankets I could find, I saw Freda Bedi. She and Thuthop Tulku were wending their way up the steep and winding path toward us. Once they arrived, Freda announced: "We have come to pray for you. Do you mind?"

"No. Why should I mind?" I replied glumly.

Without further delay, they sat and started chanting their prayers. I sat in my chair and listened calmly to their chanting. About half an hour later, a sharp pain slashed through my chest and body and I felt quite odd. After minutes of this odd sensation, I felt relieved for the first time in almost two weeks. Even my breathing had become much easier for me.

After Freda and Thuthop Tulku left, I exited from all my wrappings and slipped into my warm bed. While I felt strangely like someone who had awakened from a very bad dream, I also felt as if my cold had almost disappeared. who knows ...

Chapter 3

The rain finally stopped, and I could see the entire valley spread out in front of us the next day. We decided to go down to the Kailash, and slowly wended our way down along the familiar circular path. While walking, we saw the usual scenes: Tibetan nuns carrying heavy loads of bundled leaves or wood; young Tibetan men or groups of young monks carrying tools; and as we neared the Kailash, more and more Tibetans engaged in coming and going. Near the Kailash itself, everyone seemed busy working in the gardens. A tree had been felled. and the logs were being trimmed and oiled carefully. Even placid Thuthop Tulku was running from one to another group, gesticulating and talking.

"What do you think is wrong here?" I asked. "Something must have happened, because there's an unusual amount of activity going on."

Just then Freda came running down the stairs and called out to us: "Germaine, something big is happening to us. It's a very lucky thing! We shall have a visit from one of the most important Lamas of all! His Holiness Sakya Trizin is coming to see us! Next to the Dalai Lama. he is one of the most important spiritual lights in Asia. His Holiness Sakya Trizin is supposed to be an emanation of Manjusri, the Boddhisattva of Accomplished Wisdom! What luck for you both to be able to meet him while you're here in Dalhousie!"

During the following two days of preparation, the entire place was like an ants' nest of activities until the big day came. Once the important Lama arrived, conch shells and drums sounded from early morning onward. I was told I should wait in our perch house, and that we would be summoned when it was possible to meet His Holiness Sakya Trizin.

The day passed slowly, and nobody came to our eagle's nest to visit. Our Indian lady told us, with many gestures and broken English, that the great Lama was very young, quite chubby, and did not wear the same robes other lamas wore. He dressed in a white robe, and had a deep red shawl wrapped around his shoulders. He wore his hair in long braids and has a long golden earring with blue stones hanging from one ear. Indeed, she suggested that he looked more womanish than mannish, especially with these odd accoutrements and his long braided hair style and jewelry.

By now we were very curious and waited impatiently to see him. Finally, in the late afternoon, a monk came to fetch us. He said that he would accompany us to the nunnery where the Great Lama was now teaching.

Once in the nunnery, we waited in a large dimly lit room where everything seemed wrapped in an air of mystery. Nuns I had never before seen were rushing to and fro from room to room, and many monks sat around waiting with us too. The entire place seemed both shrouded in mystery and full of excitement at the same time. From behind closed doors came the sound of chanting, interrupted only by the occasional ringing of hand-held bells and hand-drums.

Then Freda called me in a hushed voice, I entered a room lighted only by one dim light bulb. In one corner was a shrine altar from which lighted butter lamps flickered beams of illumination that morphed into nebulous shadows. There were many people in the room, but I saw only one figure before me. This was a sturdy person of medium height who seemed less a human being than a spiritual presence to which I felt deeply drawn.

Strangely too, His Holiness made an instinctive gesture directly toward me. I approached, and we looked into one another's eyes for more than a long second.

It was only when Freda, who was standing beside me, introduced us that I returned to a normal focus and reality. Then, I somewhat awkwardly presented my white prayer scarf or kathak to His Holiness, as one should. I held it out to him with both hands.

I was unable to speak a single word when presenting my scarf. It was only after a few minutes, as I was readying myself to leave, and His Holiness had placed his hands on my head to bless me that I returned consciously fully to myself again. Then, I asked softly: "May I please see you again?" He nodded yes, silently.

This was an impressive and important meeting for me. I felt strangely happy afterwards, although I could not say or define exactly why. I felt that this was a meeting with someone whom I had known all my life; or maybe someone I had known forever, even somehow known before time itself existed.

The next morning I returned to the Kailash again.

"You must have a very happy karma, Germaine," said Freda, "since it brought you so close to His Holiness yesterday."

"Yes, I felt as if I had known him always. Moreover, I think he too felt that I was not a complete stranger."

We waited together in the entry room for a while. We again heard drumming and chanting from the shrine room. After a while, Lama Thuthop came out. He made a gesture to us that His Holiness was waiting to see us again.

His Holiness greeted us with a big smile and folded hands. He made a gesture that signaled I could sit by his side on his bench-chair if I wanted. However, I felt more at ease sitting on a carpet on the floor in front of him.

Now, in the light of day, His Holiness appeared more human. His bright eyes peered at me from behind his round spectacles, and looked straight at me. His long braids were wound around his head today, and his gold and turquoise earring was suspended from a red woolen string that was wrapped around one ear. It shook whenever he moved his head.

His Holiness was not too tall but definitively of a sturdy build. The most striking part of him was not his round face or bright eyes, it was his hands. His Holiness' hands were small and delicately shaped, like the hands and fingers of the Buddhas depicted in old Tibetan paintings. They were graceful and almost childlike hands, with long and slender fingers. These hands were actually fascinating and attractive. They moved with such unusual grace when making mudras, or even simple gestures of any kind.

Our conversation started quickly and informally. The initial shyness I had experienced the previous day had left me, and His Holiness seemed more like an old friend. We talked for a long time that day. He wanted to know about France, about me and my life, and about European history. He asked many questions. His English was still somewhat limited, so Lama Thuthop translated for us when necessary. His presence helped the flow of our conversation.

At one point, Lama Thuthop interrupted with, "His Holiness says that you should come and visit him in Mussoorie."

"My next planned journey will take me back to Europe for some months," I told him; "however, if you or His Holiness will send me a note with news from time to time, when I return to Asia, I shall surely visit him in Mussoorie."

After this, I took many pictures of His Holiness. Lama Thuthop then told me that I should come into another room and meet His Holiness' 'Aunty.' ''This 'Aunty,' as we all call her, was more or less like His Holiness' mother," Lama Thuthop added with a smile. "I was also told that it was she who helped rear him after the early death of his birth mother, and somewhat later when his father's early death interrupted his education as a youth. She is important to all of us, and still cares and plans for this family, including his sister whom you will meet."

'Aunty' was a small lady whose sparse hair was parted in the middle and tied up into a gray knot. Large gold earrings dangled from her small ears. She had a fine, straight nose, tiny mouth, and a very kind smile. That smile matched the sympathetic look in her dark grayish eyes. She sat alone on a carpet-covered bench in a room that was normally reserved for His Holiness' personal use.

A large thermos of hot Tibetan tea was placed at the foot of 'Auntie's' bench, and every time her cup was emptied or cool, a Tibetan servant hurriedly refilled it. Lama Thuthop explained to 'Aunty' who Leck and I were as visitors. She nodded brightly and presented me with a large red apple. I took several photographs of her too. Then, since it was already evening, we left and climbed up to our eagle's nest. I realized then that I would meet' Aunty' again when I visited His Holiness in Mussoorie. In fact, I certainly intended to make that visit one day during a future trip to India, which I was now certain to make again.

Throughout that evening and night, Leck and I heard the steady throb of drums and the hooting sounds of conch shells in the distance. When Peter returned to the house later that night, he explained: "His Holiness is giving some special teachings to the monks." Then he added, "You've been very lucky today, Germaine, since His Holiness seemed pleased when he met and talked with you."

"I thought so too. Somehow I felt as if I had known him for a long time, and perhaps he might have felt that way too."

"Yes. I saw the meeting, and think he must have felt the same way you did."

During the same evening, we heard a rash of worrisome news over the wireless radio. It reported that political trouble was brewing again between Pakistan and India. The problem, as usual, was about the border between these two countries. When we heard this rumor too repeatedly for comfort, we set the next day for our departure from Dalhousie. Even Freda was troubled about the rumors, since we had both noticed several Indian military planes flying over our peaceful area.

Under the circumstances, it did not seem to be a good idea to stay on, and perhaps become involved in troubles whose origins and resolutions would be problematic for us. This was not the first time I had experienced similar border problems in my life. Moreover, I had already planned to return to Europe after this side-trip from Thailand.

Early the next morning, as I was finishing the last of my packing, a monk arrived with a message from Freda. Apparently that day was being dedicated to a very important religious Buddhist celebration. The message also said that this ceremony was rarely held, and that we should not miss the opportunity to witness such a rare puja to he held nearby. We agreed.

The single jeep in Dalhousie had been made available to His Holiness, and we were told to wait for its arrival too. We walked down to the main road and waited. After some time, the jeep arrived with a white-turbaned Sikh as the chauffeur. Sitting next to the driver was His Holiness, and piled in back were two attendants, a personal servant and Lama Thuthop. There was barely room for Freda and me, along with our pile of luggage and other odd packets.

Arrangements had to be made. Therefore, almost immediately Freda asked for the jeep to stop. She arranged to have our luggage offloaded at a nearby hotel where we would stay for our last night in Dalhousie. She then instructed the driver to return after delivering us to pick up Leck who would wait here, and drive her to where the ceremony was being held.

So off we went again. Our first stop was to visit a very old Lama who was unable to attend the ceremony due to his advanced age. The jeep next maneuvered down a steep hill, even though the road had become almost too narrow. The chauffeur often found it difficult going, especially because so many people were running alongside our jeep to receive a blessing or quick touch from His Holiness Sakya Trizin.

It took considerable skill in driving before we arrived at our destination, which turned out to be another small house. We saw several monks and another 'ancient' Lama awaiting the arrival of His Holiness outside. We all entered the house together, and His Holiness was soon seated on his special high chair. The rest of us sat on long benches with small tables in front of us. We were first served the traditional guests' small dish of sweet rice and tea.

Later, for the first time in my life, I was formally served Tibetan butter tea. It was poured from a great silver kettle into a tiny cup placed in front of me. I didn't think it had a bad taste. Instead, I thought it was a strange but not disagreeable drink that resembled an amorphous too salty hotel soup. It was different from any normal tea I had ever known or been served before, but I could see its value here.

After our tea, we were again guided on our way. We climbed back into the jeep, only to discover the chauffeur had a very difficult time turning it around. We finally returned to the main road, and discovered that following it was every bit as perilous as our original downhill descent had been. All along the way, the road was crowded with Tibetans. There were young and old men twirling their prayer wheels and reciting the beads of their rosaries while walking. There were women walking with hands folded and holding burning incense sticks. Those with children held them up near the jeep for His Holiness to bless them in passing. We continued on our pilgrimage. but stopped once more to visit other very old lamas who were unable to attend the main ceremony. His Holiness blessed them in passing.

Finally, the jeep climbed upward again; however, when the road became even more steep and narrow, we were asked to descend and walk the remainder of the way.

We finally came to the location for the ceremony, which was to be held outdoors. It consisted of a large grassy meadow with row upon row of monks and lamas sitting cross-legged on the grass. Each one held a flower in his hand. There was also a crowd of lay people sitting in back of and around the monks. There were many women dressed in traditional Tibetan chubas worn under their colorful striped aprons. Most sat holding their children. There were long-haired Tibetan men of all ages, as well as a number of local Indian people from Dalhousie. A large group of various foreigners had also come to see and hear the great Lama deliver his teaching. Among this group, the majority were garbed in the usual casual 'hippie' fashion.

A white open-sided tent had been erected in one part of the meadow. In the center of the tent stood a high wooden chair (in lieu of a Lotus Throne) for His Holiness Sakya Trizin. Nearby was placed a large gold-framed photograph of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Near this photo, a large thanka of the Buddha had been pinned to one of the tent walls. On the table in front of His Holiness' throne-chair, a Vajra, a special Bell, and several other ritual or ceremonial objects were readied for use.

The ceremony in the meadow began immediately. As His Holiness started to chant the opening prayer, most of the monks and lamas joined with him. His Holiness combined the chanted prayers with specific and intricate hand movements or mudras.

I observed that the ritual hand movements resembled a dance of raised arms and hands, plus joined, flexed and released fingers. The prayer delivered was long. Once the chanting and prayers ended, His Holiness blessed everyone present by touching the Vajra to the head of each passing participant. This blessing was followed by additional blessings given by three lamas. The first lama placed a red or green string around the neck of each person; the second one poured some lotion from a silver chabai into the hand of each person, some of which was swallowed, and the rest was swiped across the head. The third lama gave each person a tiny barley cake to be eaten later. This procedure sometimes follows certain ceremonies as a special physical blessing that is thus related to the body, spirit and mind.

-

I waited to receive my blessing until all the monks and lay people had been served theirs. After receiving this final blessing, I felt strangely free and very happy once again.

We noticed that His Holiness had finally stepped down from his raised seat and disappeared into the crowd of lamas. After this, Leck, who had arrived during the ceremony, and I left the meadow. We were driven back to the hotel to spend the last night before our departure in the morning.

We left the next morning for Delhi, but somehow I knew I would visit His Holiness again, either here or in another place in India. I also hoped to see Freda again.

This time our return bus trip up and down the hills back to Pathankot was not in the 'Kashmir Tiger,' but in the 'Hill Express.' While I could not say that the trip was easier or more pleasant, the current political border problems meant that the roads were heavily occupied by military trucks and convoys; therefore. the forced slower speed of the bus made the return ride much less back-breaking for us packed-in passengers. Even the aisles were used for seating. since the news of possible strife was ominous.

Once back in the crowds of Pathankot, we returned to that other world in feeling: that of being among hectic crowded activities. We quickly learned that the political border crisis had become even worse than we had imagined. Most adolescent Indian boys wandered about with transistor radios dangling around their necks. Their faces had grim expressions from the news they were hearing. The atmosphere was permeated with an explosive feeling of tension, and the Pathankot area was filled with a military presence. We were told that we should take the next train to Delhi, since it might well be the last one to leave Pathankot for a long time.

By the time we finally arrived in Delhi, I realized just how serious the border problem had become. Because of the touchy situation between Pakistan and India, we were advised to depart India on the next possible international plane. We made rapid departure arrangements and, in fact, ours plane was the last one to leave India and not be grounded when flying over Karachi.

We left, but I continued to worry about the friends and refugees left behind in Dalhousie. After all, that area was not too far from the troubled spots. Later I received the good news that no harm had come to the Kailash, or to anyone living nearby it in Dalhousie. I was much relieved.

_______________

Notes:

Dalhousie is situated in the northern Himachal Pradesh area, actually only about forty some miles from Pathankot, or about three hours (theoretically) by bus or taxi on a difficult road. Dalhousie was home to one of the earliest Tibetan refugee communities about the 1950 exodus of His Holiness the Dalai Lama from Tibet. After his successful flight from Tibet, the roads and trails were immediately flooded with as many refugees as could muster the courage to escape. Hundreds wanted to free themselves from Chinese occupied Tibet, and most directed their steps toward areas of northern India. Thus, one of the earliest fully functional schools, the ‘Central School for Tibetans,’ was founded in this community. Perhaps consulting a map is suggested here, because visualizing the different hill station locations makes it easier to understand the cluster of Tibetan refugee centers situated in these northern to more central areas of India. The editor was unable to find a single map which locates all the settlements noted in the Memoir.

Dalhousie was founded by Lord Dalhousie in 1854, during the early days of the nearly century-long Raj colonial occupation of India. Like other hill stations, Dalhousie became a popular place to which British government or military commands often moved their offices during the summer, since it is at the on-average 6,463 foot level of elevation, and thus avoids the numbing heat of the Indian plains and capital of Delhi. It still remains a popular summer resort, and is renowned for its Victorian left-over houses and hotels constructed during the Raj. Some of these buildings became schools, and others became small hotels.

Dalhousie is also known as the place where many educational schools of quality were situated, some of which are still operative. The favorite British shopping stores and restaurants were located in the central part of this station. As in other hill stations, the popular Raj-favored Indian restaurant chefs early learned to cook the inevitable British-preferred non-spicy meat and potato dishes, drab first-served soups, and post entrée puddings the Raj colonials preferred for dessert.

It is amusing to read the few Indian-Raj cookbooks that eventuated during that long Colonial occupation. The editor found and bought one copy as a kind of ‘collectors’ item. While it might have once been popular as a guide for Indian colonial cooks, who were typically men, I doubt it would have ‘many takers’ among Indian chefs today. The recipes are nothing traditionally Indian, except by name. They are bland and compulsively repetitive, and with too many ‘toned down’ sauces to be interesting.

For those interested in actual Indian cookery, there are now many excellent Indian recipes given online, some of which can be visited under Raj-styled Indian dishes or recipes, with pictures to visualize the dish. Indian food is often of interest to vegetarian-prone eaters, because of its many non-meat traditional dishes that have spicy sauces without chilis, which makes them flavorful, but not too hot.

Dalhousie, like most hill stations, has many beautiful gardens, lovely mountain vistas, and a moderate climate, except during the cool rainy season. Its good central location was another factor that contributed to its early popularity as a Raj hill station. The surrounding land is more suited to animal shepherding than farming, since the soil is stony and not well suited for most crops. Hunting was also good in the Dalhousie area, so the military enjoyed the city and its environs for their ‘sporting’ potential too….

The first school for Tibetan Lamas as tulkus was established with Nehru’s express permission, and supported primarily by Christopher Hills, a British-born author, philosopher and scientist. The first Abbot of the school was Karma Thinley Rinpoche, and Chogyal Trumpa assisted him as the spiritual Advisor. Although more Kagyu in its early orientation, as was its leader, Freda Bed, the school later directed its educational programs toward all four Tibetan Schools of interpretation, and became a growing fountain of productivity through the decades. As it grew, it accepted Indian aid, and other than Tulkus and Tibetans as students. Finally, it thereby gained a much larger enrollment, including local Indian students.

It should be noted that the Kailash School for Lamas in Dalhousie continued to operate under the leadership of Freda Bedi for some more months. At that time, the new post-Freda leadership changed its orientation and student body to include a wider spectrum of students, since Freda wanted to return to Gangtok. Under new leadership, the school continued.

When Freda left Dalhousie to study in Gangtok, Sikkim, with Karmapa, she was later declared to be a ‘high and special status Kagyu nun,’ and became known internationally as ‘Sister Palmo,’ or ‘Kechog Palmo.’…

The summer 1965 and later border skirmish was series, but was ultimately mitigated through diplomacy, and the assistance of the United Nations to which India had referred this recurring problem. It did last until late September with threats from both sides; however, ultimately the controversy was resolved without any seriously anticipated military engagements.

It was shortly after this period that Freda Bedi ended her work at the Kailash for Tibetan Tulkus. She had apparently decided to return and study against with Karmapa in Gangtok Kagyu monastery and temple in Sikkim. She was already a nun, but wanted to focus more on Buddhist philosophy. Thus, the school continued, but was refigured to include a wider spectrum of students as suggested.

Meanwhile, sometime in 1966, Germaine decided to sever her ties with the Oriental Hotel, of which she had been a part owner and developer since after World War II. When she returned to Bangkok from a few months in Europe, she sold her shares in April of 1966 [Wikipedia says 1967]. She planned to travel and spend part of her time in Europe (Paris mostly), as well as occasional trips to Asia, including India. However, she apparently knew by this time that she would eventually return to north India to be near Sakya Trizin and his family as well.

Chapter 2

After this visit with Freda, I planned to return to Europe for several months. I had only planned to stop briefly in Delhi on my way to Europe from Thailand, where I still lived and worked. I sometimes returned to Europe via Delhi, since good direct transport to Europe is still scarce in Thailand. Now I had already stayed more time here than planned, and was anxious to leave as previously arranged.

I had again returned to Thailand, but not to work for too long, and eventually traveled on to India. On this return to India [1965?], I was accompanied by a young Siamese companion: a girl named Leck. She was a friend who had often worked for me while I lived in Bangkok, during my twenty or so years of living and working in Thailand, before I decided to retire in 1966.

During this trip to India, I wanted to avoid the usual manner of tourist travels. During previous visits to India,. I had been in the controlling orbit of tourist organizations. I stayed only in the recommended big tourist hotels, and used only tourist guides. Even my visits to the South of India had been in privately hired cars with drivers and guides. During this trip, I was determined to escape the same tourism orbit. Therefore, somewhat courageously I purchased two seats on the Kashmir Express -- first class sleeper -- all the way to Pathankot, the terminus of the railway. From there, a local bus or shared taxi would carry us on to Dalhousie, where I hoped to visit with Freda Bedi. I wanted to see how her work was progressing with the Tibetan tulkus whom I had met at the Thai reception in Delhi (in the winter, near the end of 1962.

The Kashmir Express was actually quite a comfortable train. Clean bedding was provided for first class passengers, and the four private compartment ventilator fans all worked properly. According to the schedule, having left Delhi about midnight, we were to arrive in Pathankot by 8:00 AM., the next morning. I had a sound sleep that night, but when I awakened my companion Leck said, "You know, Germaine, it seems we are almost about eight hours late."

"What do you mean eight hours late? That's impossible!"

"But I think that is what the porter man said."

I soon found that Leck's statement was unfortunately true. I learned that we were indeed nearly eight hours late. Apparently our train had run into another train on the same rail track, but going the opposite direction. Thus, a wait of several hours to correct this flaw was inevitable. Now we were very late. Soon enough, it started to become very hot inside our compartment. An Indian gentleman, a neighbor in the next compartment, had passed our door several times. He appeared especially interested in my little Thai companion, and therefore proved very helpful to us about securing our breakfast.

I complained to this gentleman that I was worried about our schedule. There was only one daily bus to Dalhousie, and now it would have left long before our late arrival. I asked, "Is it possible to hire a taxi in Pathankot?"