Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

B. K. S. Iyengar

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/30/20

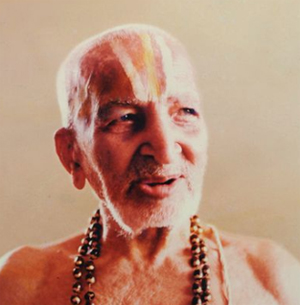

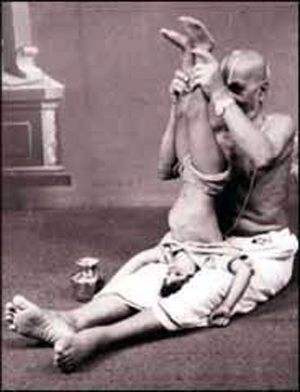

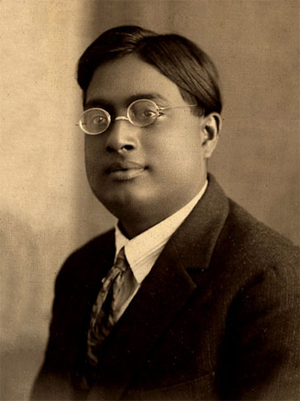

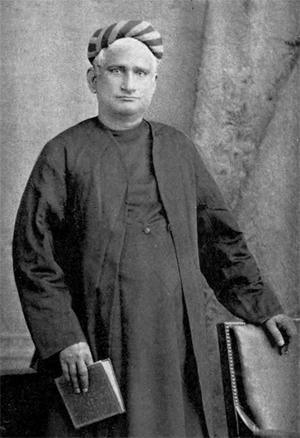

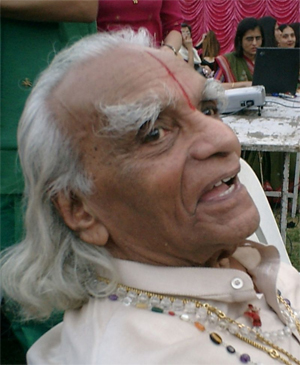

B.K.S. Iyengar

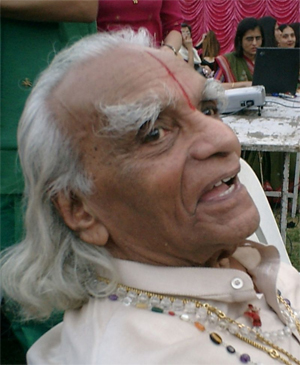

Iyengar on his 86th birthday in 2004

Born: 14 December 1918, Bellur, Kolar district, Kingdom of Mysore (now Karnataka, India)

Died: 20 August 2014 (aged 95), Pune, Maharashtra, India

Occupation: Yoga teacher, author

Known for: Iyengar Yoga

Spouse(s): Ramamani

Children: Geeta and 5 others

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar (14 December 1918 – 20 August 2014), better known as B.K.S. Iyengar, was the founder of the style of yoga as exercise known as "Iyengar Yoga" and was considered one of the foremost yoga teachers in the world.[1][2] He was the author of many books on yoga practice and philosophy including Light on Yoga, Light on Pranayama, Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and Light on Life. Iyengar was one of the earliest students of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who is often referred to as "the father of modern yoga".[3] He has been credited with popularizing yoga, first in India and then around the world.[4]

The Indian government awarded Iyengar the Padma Shri in 1991, the Padma Bhushan in 2002 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2014.[5][6] In 2004, Iyengar was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine.[7][8]

Early years

B.K.S. Iyengar was born into a poor Sri Vaishnava Iyengar family[9] in Bellur, Kolar district,[10] Karnataka, India. He was the 11th of 13 children (10 of whom survived) born to Sri Krishnamachar, a school teacher, and Sheshamma.[11] When Iyengar was five years old, his family moved to Bangalore. Four years later, the 9-year-old boy lost his father to appendicitis.[11]

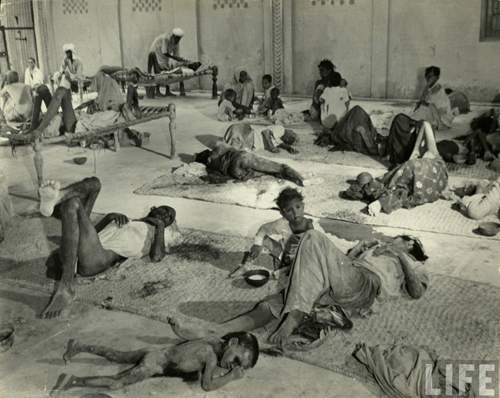

Iyengar's home town, Bellur, was in the grip of the influenza pandemic at the time of his birth, and an attack of that disease left the young boy sickly and weak for many years. Throughout his childhood, he struggled with malaria, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and general malnutrition. "My arms were thin, my legs were spindly, and my stomach protruded in an ungainly manner," he wrote. "My head used to hang down, and I had to lift it with great effort."[12]

Education in yoga

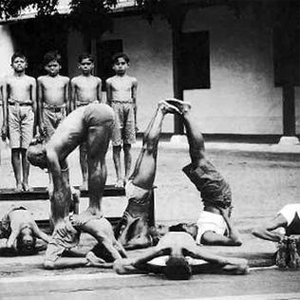

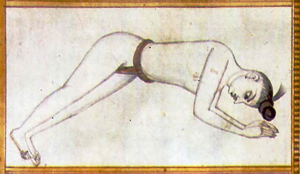

In 1934, his brother-in-law, the yogi Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, asked the 15-year-old Iyengar to come to Mysore, so as to improve his health through the practice of yoga asanas.[11][13] Krishnamacharya had Iyengar and other students give asana demonstrations in the Maharaja's court at Mysore, which had a positive influence on Iyengar.[11][14] Iyengar considers his association with his brother-in-law a turning point in his life[11] saying that over a two-year period "he (Krishnamacharya) only taught me for about ten or fifteen days, but those few days determined what I have become today!"[15] K. Pattabhi Jois has claimed that he, and not Krishnamacharya, was Iyengar's guru.[16] In 1937, Krishnamacharya sent Iyengar to Pune at the age of eighteen to spread the teaching of yoga.[11][17]

Though Iyengar had very high regard for Krishnamacharya,[15] and occasionally turned to him for advice, he had a troubled relationship with his guru during his tutelage.[18] In the beginning, Krishnamacharya predicted that the stiff, sickly teenager would not be successful at yoga. He was neglected and tasked with household chores. Only when Krishnamacharya's favorite pupil at the time, Keshavamurthy, left one day did serious training start.[19] Krishnamacharya began teaching a series of difficult postures, sometimes telling him to not eat until he mastered a certain posture. These experiences would later inform the way he taught his students.[20]

Iyengar reported in interviews that, at the age of 90, he continued to practice asanas for 3 hours and pranayamas for an hour daily. Besides this, he mentioned that he found himself performing non-deliberate pranayamas at other times.[15][18]

International recognition

Further information: Iyengar Yoga

In 1954, the violinist Yehudi Menuhin invited Iyengar to teach in Europe.

In 1952, Iyengar befriended the violinist Yehudi Menuhin.[21] Menuhin gave him the opportunity that transformed Iyengar from a comparatively obscure Indian yoga teacher into an international guru. Because Iyengar had taught the famous philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, he was asked to go to Bombay to meet Menuhin, who was known to be interested in yoga. Menuhin said he was very tired and could spare only five minutes. Iyengar told him to lie down in Savasana (on his back), and he fell asleep. After one hour, Menuhin awoke refreshed and spent another two hours with Iyengar. Menuhin came to believe that practising yoga improved his playing, and in 1954 invited Iyengar to Switzerland. At the end of that visit, he presented his yoga teacher with a watch on the back of which was inscribed, "To my best violin teacher, BKS Iyengar". From then on Iyengar visited the west regularly.[22] In Switzerland he also taught Vanda Scaravelli, who went on to develop her own style of yoga.[23]

He taught yoga to several celebrities including Krishnamurti and Jayaprakash Narayan.[24] He taught sirsasana (head stand) to Elisabeth, Queen of Belgium when she was 80.[25] Among his other devotees were the novelist Aldous Huxley, the actress Annette Bening, the film maker Mira Nair and the designer Donna Karan, as well as prominent Indian figures, including the cricketer Sachin Tendulkar and the Bollywood actress Kareena Kapoor.[12]

Iyengar made his first visit to the United States in 1956, when he taught in Ann Arbor, Michigan and gave several lecture-demonstrations; he came back to Ann Arbor in 1973, 1974, and 1976.[26]

In 1966, Iyengar published his first book, Light on Yoga. It became an international best-seller. As of 2005, it had been translated into 17 languages and sold three million copies.[2] It was followed by 13 other books, covering pranayama and aspects of yoga philosophy.[27]

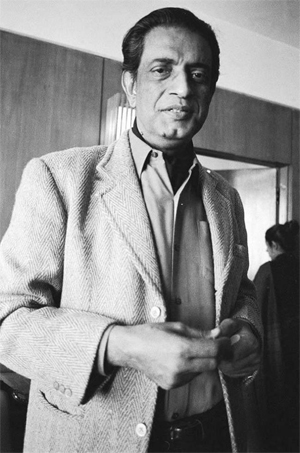

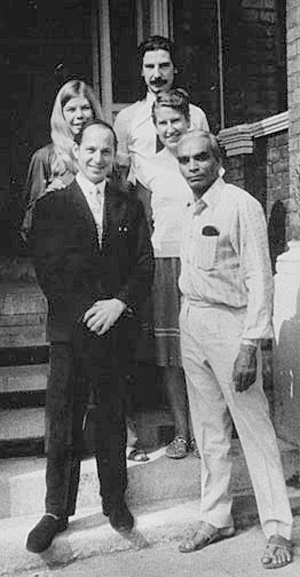

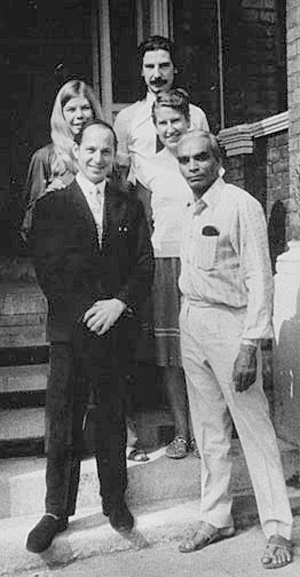

Iyengar Yoga in Britain: Iyengar with yoga teacher Malcolm Strutt at Iyengar Centre House, London, 1971

In 1967, the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) called for classes in "Hatha Yoga", free of yoga philosophy, but including asanas and "pranayamas (sic)" suitable especially for people aged over 40. The ILEA's Peter McIntosh watched some of Iyengar's classes, was impressed by Light on Yoga, and from 1970 ILEA-approved yoga teacher training in London was run by one of Iyengar's pupils, Silva Mehta. Iyengar was careful to comply with the proscription of yoga philosophy, and encouraged students to follow their own religious traditions, rather than trying to follow his own family's Visistadvaita, a qualified non-dualism within Hinduism.[28][29]

In 1975, Iyengar opened the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute in Pune, in memory of his late wife. He officially retired from teaching in 1984, but continued to be active in the world of Iyengar Yoga, teaching special classes, giving lectures, and writing books. Iyengar's daughter, Geeta, and son, Prashant, have gained international acclaim as teachers.[8]

Iyengar attracted his students by offering them just what they sought – which tended to be physical stamina and flexibility.[18] He conducted demonstrations and later, when a scooter accident dislocated his spine, began exploring the use of props to help disabled people practice Yoga. He drew inspiration from Hindu deities such as Yoga Narasimha and stories of yogis using trees to support their asanas.[20] He was however thought by his students to be somewhat rough with his adjustments when setting people into alignment; the historian of yoga Elliott Goldberg records that, as well as being known for barking orders and yelling at students,[30] he was nicknamed, based on his initials B. K. S., "Bang, Kick, Slap".[30] In Goldberg's view, Iyengar "rationalized his humiliation of his followers as a necessary consequence of his demand for high standards",[31] but this was consistent with his childhood response to the rough and abusive treatment he received from Krishnamacharya, taking offence quickly, being suspicious of other people's intentions, and belittling others: "In other words, he sometimes behaved like Krishnamacharya".[31] Goldberg concludes, however, that Iyengar hid "a compassion of which Krishnamacharya was never capable", and his students remembered his playfulness as well as his unpredictable temper.[31]

Philanthropy and activism

Iyengar supported nature conservation, stating that it is important to conserve all animals and birds.[32] He donated Rs. 2 million to Chamarajendra Zoological Gardens, Mysore, thought to be the largest donation by an individual to any zoo in India.[32] He also adopted a tiger and a cub in memory of his wife, who died in 1973.[32]

Iyengar helped promote awareness of multiple sclerosis with the Pune unit of the Multiple Sclerosis Society of India.[33]

Iyengar's most important charitable project involved donations to his ancestral village of Bellur, in the Kolar district of Karnataka. Through the Bellur Trust fund which he established, he led a transformation of the village, supporting a number of charitable activities there. He built a hospital, India's first temple dedicated to Patanjali, a free school that supplies uniforms, books, and a hot lunch to the children of Bellur and the surrounding villages, a secondary school, and a college.[34]

Family

In 1943, Iyengar married 16-year-old Ramamani in a marriage that was arranged by their parents in the usual Indian manner. He said of their marriage: "We lived without conflict as if our two souls were one."[22] Together, they raised five daughters and a son. Ramamani died in 1973 aged 46; Iyengar named his yoga institute in Pune, the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute, after her.[35]

Both Iyengar's eldest daughter Geeta (1944-2018) and his son Prashant have become internationally-known teachers in their own right. His other children are Vanita, Sunita, Suchita, and Savita.[36] Geeta, having worked extensively on yoga for women, published Yoga: A Gem for Women (2002); Prashant is the author of several books, including A Class after a Class: Yoga, an Integrated Science (1998), and Yoga and the New Millennium (2008). Since Geeta's death, Prashant has served as the director of the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute (RIMYI) in Pune.[37] Iyengar's granddaughter, Abhijata Sridhar Iyengar, trained for a number of years under his tutelage, and is now a teacher both at the Institute in Pune and internationally.

Iyengar died on 20 August 2014 in Pune, aged 95.[38][39]

Legacy

3 October 2005 was declared as "B.K.S. Iyengar Day" by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.[2] Anthropologist Joseph S. Alter of the University of Pittsburgh stated that Iyengar "has by far had the most profound impact on the global spread of yoga."[2] In June 2011, he was presented with a commemorative stamp issued in his honour by the Beijing branch of China Post. At that time there were over thirty thousand Iyengar yoga students in 57 cities in China.[40]

The noun "Iyengar", short for "Iyengar Yoga", is defined by Oxford Dictionaries as "a type of Hatha yoga focusing on the correct alignment of the body, making use of straps, wooden blocks, and other objects as aids in achieving the correct postures."[41]

On 14 December 2015, what would have been Iyengar's 97th birthday, he was honoured with a Google Doodle. It was shown in India, North America, much of Europe, Russia, and Indonesia.[42]

Bibliography

• (1966; revised ed. 1977) Light on Yoga. New York: Schocken. ISBN 978-0-8052-1031-6

• (1981) Light on Pranayama: The Yogic Art of Breathing. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0-8245-0686-3

• (1985) The Art of Yoga. Boston: Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-149062-6

• (1988) The Tree of Yoga. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-464-X

• (1996) Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. London: Thorsons. ISBN 978-0-00-714516-4

• (2005) Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. (with Abrams, D. & Evans, J.J.) Pennsylvania: Rodale. ISBN 1-59486-248-6

• (2007) Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-3362-2

• (2000–2008) Astadala Yogamala: Collected Works (8 vols) New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

• (2009) Yoga Wisdom and Practice. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7566-4283-3

• (2010) Yaugika Manas: Know and Realize the Yogic Mind. Mumbai: Yog. ISBN 81-87603-14-3

• (2012) Core of the Yoga Sutras: The Definitive Guide to the Philosophy of Yoga. London: HarperThorsons. ISBN 978-0007921263

References

1. Aubrey, Allison. "Light on life: B.K.S. Iyengar's Yoga insights". Morning Edition: National Public Radio, 10 November 1995. (full text) Retrieved 4 July 2007

2. Jump up to:a b c d Stukin, Stacie (10 October 2005). "Yogis gather around the guru". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

3. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2000). Astadala Yogamala. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 978-8177640465.

4. Sjoman 1999, p. 41.

5. "Ruskin Bond, Vidya Balan, Kamal Haasan honoured with Padma awards". Hindustan Times. HT Media Limited. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

6. "Padma Awards Announced". Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 26 January2014.

7. 2004 TIME 100 – B.K.S. Iyengar Heroes & Icons, TIME.

8. Iyengar, B.K.S. "Yoga News & Trends – Light on Iyengar". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

9. "B. K. S. Iyengar Biography". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

10. Iyengar, B.K.S. (1991). Iyengar – His Life and Work. C.B.S. Publishers & Distributors. p. 3.

11. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2006). Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. USA: Rodale. pp. xvi–xx. ISBN 9781594865244. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

12. "B. K. S. Iyengar, Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West, Dies at 95". The New York Times. 21 August 2014.

13. Smith & White 2014, p. 124.

14. Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 184, 192. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

15. Interview by R. Alexander Medin. "3 Gurus, 48 Questions" (PDF). Namarupa (Fall 2004): 9. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

16. Sjoman 1999, p. 49.

17. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2000). Astadala Yogamala. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-8177640465.

18. "Being BKS Iyengar: The enlightened yogi of yoga(part1-2)". YouTube. 22 June 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

19. Pag, Fernando. "Krishnamacharya's Legacy". Yogajournal.com. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

20. "Being BKS Iyengar: The enlightened yogi of yoga(part2-2)". YouTube. 22 June 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

21. SenGupta, Anuradha (22 June 2008). "Being BKS Iyengar: The yoga guru". IBN live. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

22. "BKS Iyengar obituary". The Guardian. 20 August 2014.

23. Wishner, Nan (5 May 2015). "The Legacy of Vanda Scaravelli". Yoga International.

24. "Life is yoga, yoga is life". Sakal Times. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

25. "Light on Iyengar". Yoga Journal. San Francisco: 96. September–October 2005. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

26. "Yogacharya B. K. S. Iyengar Dies August 20" (PDF). IYNAUS. 20 August 2014.

27. "au:B. K. S. Iyengar". WorldCat. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

28. Newcombe 2007.

29. Newcombe 2019, pp. 99, 236-239.

30. Goldberg 2016, p. 382.

31. Goldberg 2016, p. 384.

32. "Zoo felicitates B.K.S. Iyengar". The Hindu. 10 June 2009.

33. "BKS Iyengar to participate in multiple sclerosis awareness drive". The Indian Express. 22 May 2010. Retrieved 9 January2013.

34. "Bellur Trust". Iyengar Yoga UK. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

35. "The Pune Institute". Iyengar Yoga (UK). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

36. BKS Iyengar Archive Project 2007. IYNAUS. 2007. [ISBN unspecified]

37. Biography: Geeta Iyengar

38. "Yoga guru B. K. S. Iyengar passes away". The Hindu. 20 August 2014.

39. "B. K. S. Iyengar, Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West, Dies at 95". The New York Times. 20 August 2014. B. K. S. Iyengar ... died on Wednesday in the southern Indian city of Pune. He was 95. ... The cause was heart failure, said Abhijata Sridhar-Iyengar, his granddaughter. ...

40. Krishnan, Ananth (21 June 2011). "Indian yoga icon finds following in China". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 22 June2011.

41. Oxford Dictionaries. "Iyengar". Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

42. "97th birthday of B. K. S. Iyengar". Google Doodles Archive. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Sources

Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga :The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209.

——— (2019). Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Bristol, England: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78179-661-0.

Smith, Frederick M.; White, Joan (2014). Singleton, Mark; Goldberg, Ellen (eds.). Chapter 6. Becoming an Icon: B. K. S. Iyengar as a Yoga Teacher and a Yoga Guru. Gurus of Modern Yoga. Oxford University Press. pp. 122–146. ISBN 978-0-19-993871-1.

Sjoman, Norman E. (1999). The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. New Delhi, India: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.

External links

• Official website

• B. K. S. Iyengar on IMDb

• BBC World Service article and programme by Mark Tully

• Leap of faith (2008), Trivedi & Makim, Documentary about the life of BKS Iyengar

• BKS Iyengar – 97th birthday on YouTube. Google Doodle Collection. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

• BKS Iyengar Google Doodle. 97th Birthday of "Iyengar Yoga" Founder on YouTube. Rajamanickam Antonimuthu. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

• Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute at Google Cultural Institute

**************************

Yoga Reconsiders the Role of the Guru in the Age of #MeToo

by Eliza Griswold

The New Yorker

July 23, 2019

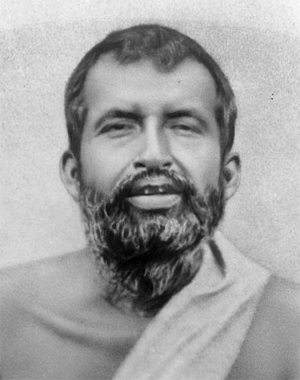

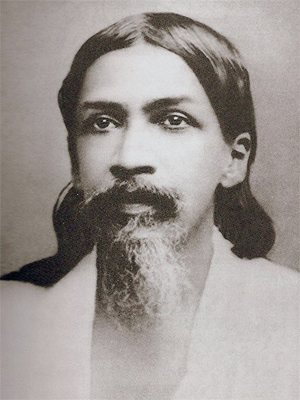

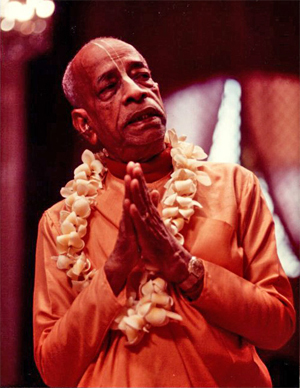

In the Western context, yoga gurus such as Sharath Jois and Bikram Choudhury (pictured) become rock stars, and students compete for their favor.Photograph by Bob Riha, Jr. / Getty

Last week on Instagram, Sharath Jois, a grandson of Pattabhi Jois, the hugely influential founder of Ashtanga yoga, which has millions of followers worldwide, finally responded to several years’ worth of claims of sexual misconduct against his grandfather, who died in 2009, at the age of ninety-three. Since 2010, more than a dozen former students have come forward to accuse Guruji, as his followers called him, of sexually assaulting them in his yoga studio in Mysore, India, and during workshops while he was on tour in the United States. Their allegations include that he rubbed his genitals against their pelvises while they were in extreme backbends, lay on top of them while they were prostrate on the floor, and inserted his fingers into their vaginas—an action that fellow-students excused as an adjustment to their mula bandhas, the body’s lowest chakra, which lies between the genitals and the anus. After his grandfather’s death, Sharath became the director of the Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute, and the paramguru (or “guru’s guru”) of Ashtanga. “It brings me immense pain that I also witness him giving improper adjustments,” Sharath wrote in the post. “I am sorry it caused pain for any of his students. After all these years I still feel pain from my grandfather’s actions.”

This is only the latest in a string of scandals involving powerful men within the yoga community that date back decades. In 1991, protesters accused Swami Satchidananda, the famous yogi who issued the invocation at Woodstock, of molesting his students, and carried signs outside a hotel where he was staying in Virginia that read “Stop the Abuse.” (Satchidananda denied all claims of misconduct.) In 1994, Amrit Desai, the founder of the Kripalu Centre for Yoga, a well-known yoga-retreat center, was accused of sleeping with his students while purporting to practice celibacy. (Desai eventually admitted to having sexual contact with three women.) More recently, Bikram Choudhury, the founder of “hot,” or Bikram, yoga, has faced several civil lawsuits for sexual misconduct, including one filed in 2013 by his own lawyer, Minakshi Jafa-Bodden, who said that he not only harassed her but also forced her to cover up allegations of misconduct against other women. (Bikram has denied all allegations.) After Bikram failed to pay Jafa-Bodden a seven-million-dollar judgment issued against him by a California court, in 2017, the judge issued an arrest warrant, and Bikram reportedly fled the country. In 2012, John Friend, the founder of Anusara yoga, admitted to sleeping with several students. He was also accused of running a Wiccan coven called Blazing Solar Flames, where members often went naked. (In a public statement, Friend denied any involvement in “a sex coven.”) Friend withdrew for a time from public life but has since launched another form of yoga, called Sridaiva. Not all of the recent scandals have been sexual; some have involved financial impropriety or the physical abuse of students. During his workshops, B. K. S. Iyengar, who died in Pune, India, in 2014, openly slapped and kicked his students while telling them, according to the Times of India, “It’s not you I’m angry with, not you I kick. It’s the knee, the back, the mind that is not listening.”

Jois was born in 1915, in the rural village of Kowshika, in South India, and spent the first thirty-two years of his life living under British colonial rule. One day at school, when he was twelve, he attended a lecture in which a yoga instructor named Sri Krishnamacharya demonstrated several asanas, or poses. Jois ran away from home at fourteen, reunited with Krishnamacharya a few years later, and proceeded to study with him for twenty-five years. He went on to create Ashtanga, a form of yoga that involves a series of rigorous athletic poses that students are encouraged to practice six times a week. Beginning in the seventies, students flocked to Mysore to study with Jois, and, as his following grew, so did his fame and influence. Some students stayed in Mysore for months or even years to perfect their poses. Others came to venerate the teacher, prostrating themselves at his feet. Female students later complained that he sometimes kissed them on the mouth without their consent, and patted their buttocks when they hugged him or bowed before him. Jubilee Cooke, a fifty-three-year-old former student who says that she was groped by Jois during yoga sessions, didn’t realize that his behavior was something that she could report. “I didn’t know it was called sexual assault until I heard political pundits talking about what Trump had done on the ‘Access Hollywood’ tapes,” she told me.

Alex Auder, the forty-eight-year-old founder of Magu Yoga, a studio in Philadelphia, has been one of Jois’s most vocal critics. During the late nineteen-nineties, Auder taught at Jivamukti, in New York City, one of the places where Ashtanga first grew popular in the United States. But, in the past decade, she has become increasingly skeptical of some aspects of the practice. Initially, her criticisms focussed on the poses themselves, which she believes Jois designed with little regard for how they would be enacted by women. “The physical practice is totally off base—it’s patriarchal,” she told me. “For many women’s bodies, it simply doesn’t work.” (To illustrate this point, she recently posted a picture on Instagram of Sharath Jois assisting a pregnant woman to “drop back” from a standing position into a backbend, which struck Auder as ill-advised.) For the past five years, Auder has written about the increasing commodification of yoga, which she calls “neo-spiritualism”—an alliance between yoga and neoliberalism. Such criticism is not taken lightly in the Ashtanga community; according to Auder and others, those who speak out are often ostracized. “Sharath kicked anyone off the list of sanctioned teachers who ever criticized Pattabhi Jois or Ashtanga,” she told me. (Sharath did not respond to requests for comment on this article.)

For Karen Rain, a fifty-one-year-old former student who says that Jois repeatedly assaulted her between 1994 and 1998, at his studio in Mysore, the fear of being ostracized kept her from telling anyone about the abuse. “I knew it would bring me criticism and slander,” she told me. She was certain that her fellow-students would turn on her if she made her allegations public, and, in 2002, she left Ashtanga. “It destroyed my life as I knew it,” she said. “I loved the practice and was hoping to build my life and career around it.” In 2018, she told her story on Medium and included photographs showing Jois pressing his crotch to hers while she lifted her leg above her head. “Since the images are still photographs, you don’t really see that he’s humping me,” she told me.

Anneke Lucas, a fifty-six-year-old former student, who now works as an advocate for survivors of sexual abuse and is the founder of Liberation Prison Yoga, confronted Jois the moment he groped her crotch, during a class in Manhattan in 2001, and told him that he could go to prison for touching her like that. After she spoke out, she felt that her experience wasn’t taken seriously by other students and teachers, which she found more harmful than the assault. “I was far more hurt by the culture of silence and ignoring the victim and victim-blaming than the abuse itself,” she told me. “If there would’ve been support from the community, and it had been dealt with, it would have gone away.” Cooke has called out the magazine Yoga Journal for favorable articles that it published about Jois in the nineties. “Whether or not they did it consciously, it was grooming,” she said. “Encouraging people to go study with Pattabhi Jois and expect good things from him.”

Last year, Auder became Facebook friends with Rain, Lucas, and Cooke, and the four began discussing what they saw as Ashtanga’s toxic sexual culture. At first, Auder wasn’t sure how to process the severity of the women’s claims. “I’m a product of the seventies,” she told me, “and I don’t mind a pat on the ass.” But as the number of accusers grew over the last year she came to see that what others called “inappropriate adjustment” was really a pattern of sexual abuse, and that the powerful following that had grown up around Jois had helped to keep his accusers silent. After that, on Instagram, she called for an official response from Ashtanga leaders.

Instead of putting the controversy to rest, the statement that Sharath issued last week has kicked off a flurry of angry responses from people who argue that it comes too late, and that it reads like an attempt to end the controversy rather than a genuine effort to set things right. Critics accused Sharath of shirking blame for himself or his family and instead accusing other students of failing to protect their fellow-practitioners. “Why did they not act in support of their fellow students, peers, girlfriends, boyfriends, wives, husbands, friends and speak against this?” he asks. He followed this up with another statement, in which he grew more defensive. “You can criticize me what ever you want,” he wrote on Instagram, punctuating his post with crying-face emojis. “I have always respected & supported women my students know it & god knows it.” The post has since been deleted.

But the scandal has prompted other leaders, including Eddie Stern, a fifty-one-year-old yoga instructor who, for twenty-five years, was the head of one of the most influential Ashtanga schools in the United States, to speak out about Jois’s abuses. Stern studied under Jois for eighteen years and has since authored three books about Ashtanga. After the allegations were made public, he received letters from current students asking him to respond. “People have considered me to be part of this problem because I haven’t spoken publicly,” he told me. Although Stern has been talking in private to concerned students and fellow-teachers, now that Sharath has issued a statement, Stern has decided to speak to me for this article.

Jois’s abuses remained hidden for so long in part because of his overwhelming authority as a guru, which may reflect a larger problem within the culture of yoga. In traditional yogic practice, a guru is a mediator—a translator of sorts—through whom a set of teachings is passed down. Devotion to the guru is meant to symbolize devotion to the teachings, not to the man. But in the Western context gurus become rock stars, and students compete to curry favor with them. This gives gurus significant influence over their students, which is sometimes misused. “I had this idea in me that the guru was supposed to be this all-encompassing everything,” Stern said. “I, along with other people, superimposed these mythologies on top of a human being . . . It was a misunderstanding of what the relationship was supposed to be.

For Rain, apologies from Ashtanga teachers have come too late. She is less interested in public statements and more interested in specific measures that schools can take to change their cultures. Some yoga communities have begun instituting official checks on how teachers are allowed to touch their students, including issuing “consent cards,” which students fill out to indicate whether they are willing to be touched and place at the edge of their mats. Rain wants Ashtanga teachers to pledge to offer free copies of articles about the accusations against Jois at their studios and to post unedited accounts of the allegations on their Web sites. She told me, “I’m offering them a way to make amends by giving the narrative to us.”

Eliza Griswold, a contributing writer covering religion, politics, and the environment, has been writing for The New Yorker since 2003. She won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction for “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America,” in 2019.

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/30/20

-- Iyengar’s Charisma of Incoherence, and Selected Indoctrination Defence Statements, by Matthew Remski

The videos below show two different instances of BKS Iyengar teaching at a yoga convention back in the 1990s.

The first one is particularly disturbing to watch. The student has cervical spondylosis and BKSI is shown dangerously pulling her out of position in Salamba Sarvangasana. Her neck could easily have been injured and she is clearly distressed by the reckless adjustment.

In the second video the student shown has lower back issues. BKSI treats his body as not much better than a slab of meat.

Can you imagine if a teacher up for certification had behaved in this way during a teaching assessment?

There is nothing admirable in this behavior. The arrogant, misplaced ownership BKSI asserts over his student's bodies is unnecessary and robs them of their personhood and self agency. He shows no sense of presence or connection to the many complex layers of the people that he is interacting with. In doing so, he leads them straight into harm's way.

There will be many ardent devotees who will try to explain this behavior away. Some will even try to glorify it. They will tell you not to believe what your eyes and gut are telling you about the violence you see. But once you strip the spiritual veneer away, that's what it is, violence, plain and simple.

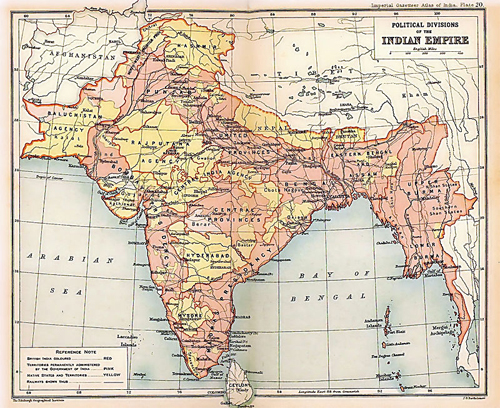

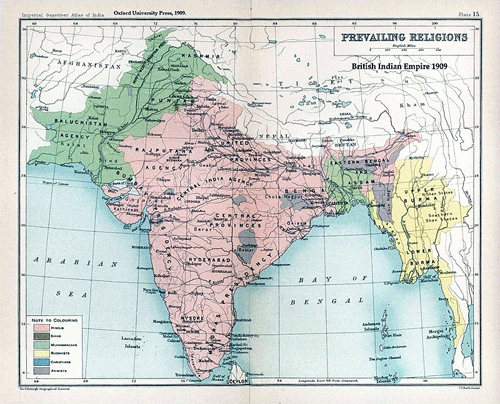

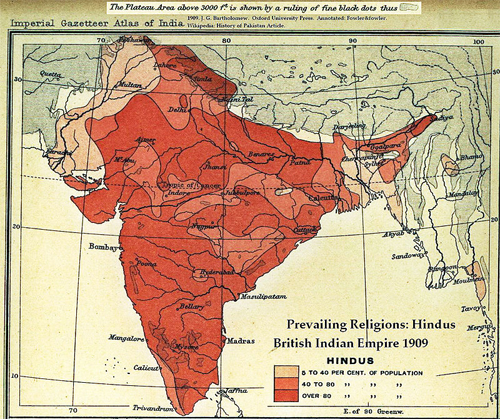

I'm not denying BKS Iyengar's otherwise remarkable knowledge. But his delivery of that knowledge was mired in another, more brutal era. His methods were infused with the Indian caste culture and impacted by the British colonial rule that he was born into. Add to that the abuse that he suffered at the hands of his own teacher and you have a merciless, severe teaching style that has no place in contemporary culture.

I thoroughly reject the ongoing tradition in Iyengar Yoga of teachers treating another person's body with ownership and such a lack of care. Body treated as object, versus body treated as part of the continuum of the Self.

Let's keep the best of what BKSI had to offer and leave the rest behind. Or, as a dear friend said, "compost what is harmful so we can grow something healing and beautiful."

Our body should not be forced or punished like this. It should be honored and revered as temple to our Soul. Iyengar Yoga needs to and can evolve. It would be sad to see it become trapped in this wounded and antiquated type of behavior. Obsolete and lost to the wrong side of history.

Cassie Jackson

Liz Anne Potamianos

Karen Rain

Matthew Remski

Donna Farhi

-- Ann Tapsell West

B.K.S. Iyengar

Iyengar on his 86th birthday in 2004

Born: 14 December 1918, Bellur, Kolar district, Kingdom of Mysore (now Karnataka, India)

Died: 20 August 2014 (aged 95), Pune, Maharashtra, India

Occupation: Yoga teacher, author

Known for: Iyengar Yoga

Spouse(s): Ramamani

Children: Geeta and 5 others

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar (14 December 1918 – 20 August 2014), better known as B.K.S. Iyengar, was the founder of the style of yoga as exercise known as "Iyengar Yoga" and was considered one of the foremost yoga teachers in the world.[1][2] He was the author of many books on yoga practice and philosophy including Light on Yoga, Light on Pranayama, Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and Light on Life. Iyengar was one of the earliest students of Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who is often referred to as "the father of modern yoga".[3] He has been credited with popularizing yoga, first in India and then around the world.[4]

The Indian government awarded Iyengar the Padma Shri in 1991, the Padma Bhushan in 2002 and the Padma Vibhushan in 2014.[5][6] In 2004, Iyengar was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine.[7][8]

Early years

B.K.S. Iyengar was born into a poor Sri Vaishnava Iyengar family[9] in Bellur, Kolar district,[10] Karnataka, India. He was the 11th of 13 children (10 of whom survived) born to Sri Krishnamachar, a school teacher, and Sheshamma.[11] When Iyengar was five years old, his family moved to Bangalore. Four years later, the 9-year-old boy lost his father to appendicitis.[11]

Iyengar's home town, Bellur, was in the grip of the influenza pandemic at the time of his birth, and an attack of that disease left the young boy sickly and weak for many years. Throughout his childhood, he struggled with malaria, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and general malnutrition. "My arms were thin, my legs were spindly, and my stomach protruded in an ungainly manner," he wrote. "My head used to hang down, and I had to lift it with great effort."[12]

Education in yoga

In 1934, his brother-in-law, the yogi Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, asked the 15-year-old Iyengar to come to Mysore, so as to improve his health through the practice of yoga asanas.[11][13] Krishnamacharya had Iyengar and other students give asana demonstrations in the Maharaja's court at Mysore, which had a positive influence on Iyengar.[11][14] Iyengar considers his association with his brother-in-law a turning point in his life[11] saying that over a two-year period "he (Krishnamacharya) only taught me for about ten or fifteen days, but those few days determined what I have become today!"[15] K. Pattabhi Jois has claimed that he, and not Krishnamacharya, was Iyengar's guru.[16] In 1937, Krishnamacharya sent Iyengar to Pune at the age of eighteen to spread the teaching of yoga.[11][17]

Though Iyengar had very high regard for Krishnamacharya,[15] and occasionally turned to him for advice, he had a troubled relationship with his guru during his tutelage.[18] In the beginning, Krishnamacharya predicted that the stiff, sickly teenager would not be successful at yoga. He was neglected and tasked with household chores. Only when Krishnamacharya's favorite pupil at the time, Keshavamurthy, left one day did serious training start.[19] Krishnamacharya began teaching a series of difficult postures, sometimes telling him to not eat until he mastered a certain posture. These experiences would later inform the way he taught his students.[20]

Iyengar reported in interviews that, at the age of 90, he continued to practice asanas for 3 hours and pranayamas for an hour daily. Besides this, he mentioned that he found himself performing non-deliberate pranayamas at other times.[15][18]

International recognition

Further information: Iyengar Yoga

In 1954, the violinist Yehudi Menuhin invited Iyengar to teach in Europe.

In 1952, Iyengar befriended the violinist Yehudi Menuhin.[21] Menuhin gave him the opportunity that transformed Iyengar from a comparatively obscure Indian yoga teacher into an international guru. Because Iyengar had taught the famous philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, he was asked to go to Bombay to meet Menuhin, who was known to be interested in yoga. Menuhin said he was very tired and could spare only five minutes. Iyengar told him to lie down in Savasana (on his back), and he fell asleep. After one hour, Menuhin awoke refreshed and spent another two hours with Iyengar. Menuhin came to believe that practising yoga improved his playing, and in 1954 invited Iyengar to Switzerland. At the end of that visit, he presented his yoga teacher with a watch on the back of which was inscribed, "To my best violin teacher, BKS Iyengar". From then on Iyengar visited the west regularly.[22] In Switzerland he also taught Vanda Scaravelli, who went on to develop her own style of yoga.[23]

He taught yoga to several celebrities including Krishnamurti and Jayaprakash Narayan.[24] He taught sirsasana (head stand) to Elisabeth, Queen of Belgium when she was 80.[25] Among his other devotees were the novelist Aldous Huxley, the actress Annette Bening, the film maker Mira Nair and the designer Donna Karan, as well as prominent Indian figures, including the cricketer Sachin Tendulkar and the Bollywood actress Kareena Kapoor.[12]

Iyengar made his first visit to the United States in 1956, when he taught in Ann Arbor, Michigan and gave several lecture-demonstrations; he came back to Ann Arbor in 1973, 1974, and 1976.[26]

In 1966, Iyengar published his first book, Light on Yoga. It became an international best-seller. As of 2005, it had been translated into 17 languages and sold three million copies.[2] It was followed by 13 other books, covering pranayama and aspects of yoga philosophy.[27]

Iyengar Yoga in Britain: Iyengar with yoga teacher Malcolm Strutt at Iyengar Centre House, London, 1971

In 1967, the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) called for classes in "Hatha Yoga", free of yoga philosophy, but including asanas and "pranayamas (sic)" suitable especially for people aged over 40. The ILEA's Peter McIntosh watched some of Iyengar's classes, was impressed by Light on Yoga, and from 1970 ILEA-approved yoga teacher training in London was run by one of Iyengar's pupils, Silva Mehta. Iyengar was careful to comply with the proscription of yoga philosophy, and encouraged students to follow their own religious traditions, rather than trying to follow his own family's Visistadvaita, a qualified non-dualism within Hinduism.[28][29]

In 1975, Iyengar opened the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute in Pune, in memory of his late wife. He officially retired from teaching in 1984, but continued to be active in the world of Iyengar Yoga, teaching special classes, giving lectures, and writing books. Iyengar's daughter, Geeta, and son, Prashant, have gained international acclaim as teachers.[8]

Iyengar attracted his students by offering them just what they sought – which tended to be physical stamina and flexibility.[18] He conducted demonstrations and later, when a scooter accident dislocated his spine, began exploring the use of props to help disabled people practice Yoga. He drew inspiration from Hindu deities such as Yoga Narasimha and stories of yogis using trees to support their asanas.[20] He was however thought by his students to be somewhat rough with his adjustments when setting people into alignment; the historian of yoga Elliott Goldberg records that, as well as being known for barking orders and yelling at students,[30] he was nicknamed, based on his initials B. K. S., "Bang, Kick, Slap".[30] In Goldberg's view, Iyengar "rationalized his humiliation of his followers as a necessary consequence of his demand for high standards",[31] but this was consistent with his childhood response to the rough and abusive treatment he received from Krishnamacharya, taking offence quickly, being suspicious of other people's intentions, and belittling others: "In other words, he sometimes behaved like Krishnamacharya".[31] Goldberg concludes, however, that Iyengar hid "a compassion of which Krishnamacharya was never capable", and his students remembered his playfulness as well as his unpredictable temper.[31]

Philanthropy and activism

Iyengar supported nature conservation, stating that it is important to conserve all animals and birds.[32] He donated Rs. 2 million to Chamarajendra Zoological Gardens, Mysore, thought to be the largest donation by an individual to any zoo in India.[32] He also adopted a tiger and a cub in memory of his wife, who died in 1973.[32]

Iyengar helped promote awareness of multiple sclerosis with the Pune unit of the Multiple Sclerosis Society of India.[33]

Iyengar's most important charitable project involved donations to his ancestral village of Bellur, in the Kolar district of Karnataka. Through the Bellur Trust fund which he established, he led a transformation of the village, supporting a number of charitable activities there. He built a hospital, India's first temple dedicated to Patanjali, a free school that supplies uniforms, books, and a hot lunch to the children of Bellur and the surrounding villages, a secondary school, and a college.[34]

Family

In 1943, Iyengar married 16-year-old Ramamani in a marriage that was arranged by their parents in the usual Indian manner. He said of their marriage: "We lived without conflict as if our two souls were one."[22] Together, they raised five daughters and a son. Ramamani died in 1973 aged 46; Iyengar named his yoga institute in Pune, the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute, after her.[35]

Both Iyengar's eldest daughter Geeta (1944-2018) and his son Prashant have become internationally-known teachers in their own right. His other children are Vanita, Sunita, Suchita, and Savita.[36] Geeta, having worked extensively on yoga for women, published Yoga: A Gem for Women (2002); Prashant is the author of several books, including A Class after a Class: Yoga, an Integrated Science (1998), and Yoga and the New Millennium (2008). Since Geeta's death, Prashant has served as the director of the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute (RIMYI) in Pune.[37] Iyengar's granddaughter, Abhijata Sridhar Iyengar, trained for a number of years under his tutelage, and is now a teacher both at the Institute in Pune and internationally.

Iyengar died on 20 August 2014 in Pune, aged 95.[38][39]

Legacy

3 October 2005 was declared as "B.K.S. Iyengar Day" by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.[2] Anthropologist Joseph S. Alter of the University of Pittsburgh stated that Iyengar "has by far had the most profound impact on the global spread of yoga."[2] In June 2011, he was presented with a commemorative stamp issued in his honour by the Beijing branch of China Post. At that time there were over thirty thousand Iyengar yoga students in 57 cities in China.[40]

The noun "Iyengar", short for "Iyengar Yoga", is defined by Oxford Dictionaries as "a type of Hatha yoga focusing on the correct alignment of the body, making use of straps, wooden blocks, and other objects as aids in achieving the correct postures."[41]

On 14 December 2015, what would have been Iyengar's 97th birthday, he was honoured with a Google Doodle. It was shown in India, North America, much of Europe, Russia, and Indonesia.[42]

Bibliography

• (1966; revised ed. 1977) Light on Yoga. New York: Schocken. ISBN 978-0-8052-1031-6

• (1981) Light on Pranayama: The Yogic Art of Breathing. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 0-8245-0686-3

• (1985) The Art of Yoga. Boston: Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-149062-6

• (1988) The Tree of Yoga. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-464-X

• (1996) Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. London: Thorsons. ISBN 978-0-00-714516-4

• (2005) Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. (with Abrams, D. & Evans, J.J.) Pennsylvania: Rodale. ISBN 1-59486-248-6

• (2007) Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-3362-2

• (2000–2008) Astadala Yogamala: Collected Works (8 vols) New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

• (2009) Yoga Wisdom and Practice. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7566-4283-3

• (2010) Yaugika Manas: Know and Realize the Yogic Mind. Mumbai: Yog. ISBN 81-87603-14-3

• (2012) Core of the Yoga Sutras: The Definitive Guide to the Philosophy of Yoga. London: HarperThorsons. ISBN 978-0007921263

References

1. Aubrey, Allison. "Light on life: B.K.S. Iyengar's Yoga insights". Morning Edition: National Public Radio, 10 November 1995. (full text) Retrieved 4 July 2007

2. Jump up to:a b c d Stukin, Stacie (10 October 2005). "Yogis gather around the guru". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

3. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2000). Astadala Yogamala. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 978-8177640465.

4. Sjoman 1999, p. 41.

5. "Ruskin Bond, Vidya Balan, Kamal Haasan honoured with Padma awards". Hindustan Times. HT Media Limited. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

6. "Padma Awards Announced". Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 26 January2014.

7. 2004 TIME 100 – B.K.S. Iyengar Heroes & Icons, TIME.

8. Iyengar, B.K.S. "Yoga News & Trends – Light on Iyengar". Yoga Journal. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

9. "B. K. S. Iyengar Biography". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

10. Iyengar, B.K.S. (1991). Iyengar – His Life and Work. C.B.S. Publishers & Distributors. p. 3.

11. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2006). Light on Life: The Yoga Journey to Wholeness, Inner Peace, and Ultimate Freedom. USA: Rodale. pp. xvi–xx. ISBN 9781594865244. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

12. "B. K. S. Iyengar, Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West, Dies at 95". The New York Times. 21 August 2014.

13. Smith & White 2014, p. 124.

14. Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 184, 192. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

15. Interview by R. Alexander Medin. "3 Gurus, 48 Questions" (PDF). Namarupa (Fall 2004): 9. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

16. Sjoman 1999, p. 49.

17. Iyengar, B.K.S. (2000). Astadala Yogamala. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-8177640465.

18. "Being BKS Iyengar: The enlightened yogi of yoga(part1-2)". YouTube. 22 June 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

19. Pag, Fernando. "Krishnamacharya's Legacy". Yogajournal.com. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

20. "Being BKS Iyengar: The enlightened yogi of yoga(part2-2)". YouTube. 22 June 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

21. SenGupta, Anuradha (22 June 2008). "Being BKS Iyengar: The yoga guru". IBN live. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

22. "BKS Iyengar obituary". The Guardian. 20 August 2014.

23. Wishner, Nan (5 May 2015). "The Legacy of Vanda Scaravelli". Yoga International.

24. "Life is yoga, yoga is life". Sakal Times. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

25. "Light on Iyengar". Yoga Journal. San Francisco: 96. September–October 2005. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

26. "Yogacharya B. K. S. Iyengar Dies August 20" (PDF). IYNAUS. 20 August 2014.

27. "au:B. K. S. Iyengar". WorldCat. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

28. Newcombe 2007.

29. Newcombe 2019, pp. 99, 236-239.

30. Goldberg 2016, p. 382.

31. Goldberg 2016, p. 384.

32. "Zoo felicitates B.K.S. Iyengar". The Hindu. 10 June 2009.

33. "BKS Iyengar to participate in multiple sclerosis awareness drive". The Indian Express. 22 May 2010. Retrieved 9 January2013.

34. "Bellur Trust". Iyengar Yoga UK. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

35. "The Pune Institute". Iyengar Yoga (UK). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

36. BKS Iyengar Archive Project 2007. IYNAUS. 2007. [ISBN unspecified]

37. Biography: Geeta Iyengar

38. "Yoga guru B. K. S. Iyengar passes away". The Hindu. 20 August 2014.

39. "B. K. S. Iyengar, Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West, Dies at 95". The New York Times. 20 August 2014. B. K. S. Iyengar ... died on Wednesday in the southern Indian city of Pune. He was 95. ... The cause was heart failure, said Abhijata Sridhar-Iyengar, his granddaughter. ...

40. Krishnan, Ananth (21 June 2011). "Indian yoga icon finds following in China". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 22 June2011.

41. Oxford Dictionaries. "Iyengar". Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

42. "97th birthday of B. K. S. Iyengar". Google Doodles Archive. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

Sources

Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga :The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209.

——— (2019). Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Bristol, England: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78179-661-0.

Smith, Frederick M.; White, Joan (2014). Singleton, Mark; Goldberg, Ellen (eds.). Chapter 6. Becoming an Icon: B. K. S. Iyengar as a Yoga Teacher and a Yoga Guru. Gurus of Modern Yoga. Oxford University Press. pp. 122–146. ISBN 978-0-19-993871-1.

Sjoman, Norman E. (1999). The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. New Delhi, India: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.

External links

• Official website

• B. K. S. Iyengar on IMDb

• BBC World Service article and programme by Mark Tully

• Leap of faith (2008), Trivedi & Makim, Documentary about the life of BKS Iyengar

• BKS Iyengar – 97th birthday on YouTube. Google Doodle Collection. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

• BKS Iyengar Google Doodle. 97th Birthday of "Iyengar Yoga" Founder on YouTube. Rajamanickam Antonimuthu. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

• Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute at Google Cultural Institute

**************************

Yoga Reconsiders the Role of the Guru in the Age of #MeToo

by Eliza Griswold

The New Yorker

July 23, 2019

In the Western context, yoga gurus such as Sharath Jois and Bikram Choudhury (pictured) become rock stars, and students compete for their favor.Photograph by Bob Riha, Jr. / Getty

Last week on Instagram, Sharath Jois, a grandson of Pattabhi Jois, the hugely influential founder of Ashtanga yoga, which has millions of followers worldwide, finally responded to several years’ worth of claims of sexual misconduct against his grandfather, who died in 2009, at the age of ninety-three. Since 2010, more than a dozen former students have come forward to accuse Guruji, as his followers called him, of sexually assaulting them in his yoga studio in Mysore, India, and during workshops while he was on tour in the United States. Their allegations include that he rubbed his genitals against their pelvises while they were in extreme backbends, lay on top of them while they were prostrate on the floor, and inserted his fingers into their vaginas—an action that fellow-students excused as an adjustment to their mula bandhas, the body’s lowest chakra, which lies between the genitals and the anus. After his grandfather’s death, Sharath became the director of the Shri K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute, and the paramguru (or “guru’s guru”) of Ashtanga. “It brings me immense pain that I also witness him giving improper adjustments,” Sharath wrote in the post. “I am sorry it caused pain for any of his students. After all these years I still feel pain from my grandfather’s actions.”

This is only the latest in a string of scandals involving powerful men within the yoga community that date back decades. In 1991, protesters accused Swami Satchidananda, the famous yogi who issued the invocation at Woodstock, of molesting his students, and carried signs outside a hotel where he was staying in Virginia that read “Stop the Abuse.” (Satchidananda denied all claims of misconduct.) In 1994, Amrit Desai, the founder of the Kripalu Centre for Yoga, a well-known yoga-retreat center, was accused of sleeping with his students while purporting to practice celibacy. (Desai eventually admitted to having sexual contact with three women.) More recently, Bikram Choudhury, the founder of “hot,” or Bikram, yoga, has faced several civil lawsuits for sexual misconduct, including one filed in 2013 by his own lawyer, Minakshi Jafa-Bodden, who said that he not only harassed her but also forced her to cover up allegations of misconduct against other women. (Bikram has denied all allegations.) After Bikram failed to pay Jafa-Bodden a seven-million-dollar judgment issued against him by a California court, in 2017, the judge issued an arrest warrant, and Bikram reportedly fled the country. In 2012, John Friend, the founder of Anusara yoga, admitted to sleeping with several students. He was also accused of running a Wiccan coven called Blazing Solar Flames, where members often went naked. (In a public statement, Friend denied any involvement in “a sex coven.”) Friend withdrew for a time from public life but has since launched another form of yoga, called Sridaiva. Not all of the recent scandals have been sexual; some have involved financial impropriety or the physical abuse of students. During his workshops, B. K. S. Iyengar, who died in Pune, India, in 2014, openly slapped and kicked his students while telling them, according to the Times of India, “It’s not you I’m angry with, not you I kick. It’s the knee, the back, the mind that is not listening.”

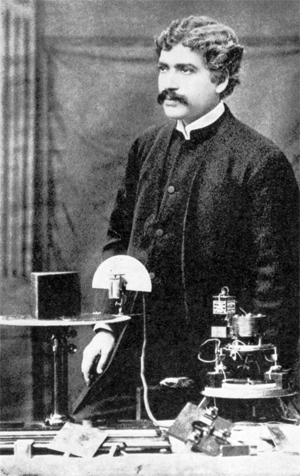

Jois was born in 1915, in the rural village of Kowshika, in South India, and spent the first thirty-two years of his life living under British colonial rule. One day at school, when he was twelve, he attended a lecture in which a yoga instructor named Sri Krishnamacharya demonstrated several asanas, or poses. Jois ran away from home at fourteen, reunited with Krishnamacharya a few years later, and proceeded to study with him for twenty-five years. He went on to create Ashtanga, a form of yoga that involves a series of rigorous athletic poses that students are encouraged to practice six times a week. Beginning in the seventies, students flocked to Mysore to study with Jois, and, as his following grew, so did his fame and influence. Some students stayed in Mysore for months or even years to perfect their poses. Others came to venerate the teacher, prostrating themselves at his feet. Female students later complained that he sometimes kissed them on the mouth without their consent, and patted their buttocks when they hugged him or bowed before him. Jubilee Cooke, a fifty-three-year-old former student who says that she was groped by Jois during yoga sessions, didn’t realize that his behavior was something that she could report. “I didn’t know it was called sexual assault until I heard political pundits talking about what Trump had done on the ‘Access Hollywood’ tapes,” she told me.

Alex Auder, the forty-eight-year-old founder of Magu Yoga, a studio in Philadelphia, has been one of Jois’s most vocal critics. During the late nineteen-nineties, Auder taught at Jivamukti, in New York City, one of the places where Ashtanga first grew popular in the United States. But, in the past decade, she has become increasingly skeptical of some aspects of the practice. Initially, her criticisms focussed on the poses themselves, which she believes Jois designed with little regard for how they would be enacted by women. “The physical practice is totally off base—it’s patriarchal,” she told me. “For many women’s bodies, it simply doesn’t work.” (To illustrate this point, she recently posted a picture on Instagram of Sharath Jois assisting a pregnant woman to “drop back” from a standing position into a backbend, which struck Auder as ill-advised.) For the past five years, Auder has written about the increasing commodification of yoga, which she calls “neo-spiritualism”—an alliance between yoga and neoliberalism. Such criticism is not taken lightly in the Ashtanga community; according to Auder and others, those who speak out are often ostracized. “Sharath kicked anyone off the list of sanctioned teachers who ever criticized Pattabhi Jois or Ashtanga,” she told me. (Sharath did not respond to requests for comment on this article.)

For Karen Rain, a fifty-one-year-old former student who says that Jois repeatedly assaulted her between 1994 and 1998, at his studio in Mysore, the fear of being ostracized kept her from telling anyone about the abuse. “I knew it would bring me criticism and slander,” she told me. She was certain that her fellow-students would turn on her if she made her allegations public, and, in 2002, she left Ashtanga. “It destroyed my life as I knew it,” she said. “I loved the practice and was hoping to build my life and career around it.” In 2018, she told her story on Medium and included photographs showing Jois pressing his crotch to hers while she lifted her leg above her head. “Since the images are still photographs, you don’t really see that he’s humping me,” she told me.

Anneke Lucas, a fifty-six-year-old former student, who now works as an advocate for survivors of sexual abuse and is the founder of Liberation Prison Yoga, confronted Jois the moment he groped her crotch, during a class in Manhattan in 2001, and told him that he could go to prison for touching her like that. After she spoke out, she felt that her experience wasn’t taken seriously by other students and teachers, which she found more harmful than the assault. “I was far more hurt by the culture of silence and ignoring the victim and victim-blaming than the abuse itself,” she told me. “If there would’ve been support from the community, and it had been dealt with, it would have gone away.” Cooke has called out the magazine Yoga Journal for favorable articles that it published about Jois in the nineties. “Whether or not they did it consciously, it was grooming,” she said. “Encouraging people to go study with Pattabhi Jois and expect good things from him.”

Last year, Auder became Facebook friends with Rain, Lucas, and Cooke, and the four began discussing what they saw as Ashtanga’s toxic sexual culture. At first, Auder wasn’t sure how to process the severity of the women’s claims. “I’m a product of the seventies,” she told me, “and I don’t mind a pat on the ass.” But as the number of accusers grew over the last year she came to see that what others called “inappropriate adjustment” was really a pattern of sexual abuse, and that the powerful following that had grown up around Jois had helped to keep his accusers silent. After that, on Instagram, she called for an official response from Ashtanga leaders.

Instead of putting the controversy to rest, the statement that Sharath issued last week has kicked off a flurry of angry responses from people who argue that it comes too late, and that it reads like an attempt to end the controversy rather than a genuine effort to set things right. Critics accused Sharath of shirking blame for himself or his family and instead accusing other students of failing to protect their fellow-practitioners. “Why did they not act in support of their fellow students, peers, girlfriends, boyfriends, wives, husbands, friends and speak against this?” he asks. He followed this up with another statement, in which he grew more defensive. “You can criticize me what ever you want,” he wrote on Instagram, punctuating his post with crying-face emojis. “I have always respected & supported women my students know it & god knows it.” The post has since been deleted.

But the scandal has prompted other leaders, including Eddie Stern, a fifty-one-year-old yoga instructor who, for twenty-five years, was the head of one of the most influential Ashtanga schools in the United States, to speak out about Jois’s abuses. Stern studied under Jois for eighteen years and has since authored three books about Ashtanga. After the allegations were made public, he received letters from current students asking him to respond. “People have considered me to be part of this problem because I haven’t spoken publicly,” he told me. Although Stern has been talking in private to concerned students and fellow-teachers, now that Sharath has issued a statement, Stern has decided to speak to me for this article.

Jois’s abuses remained hidden for so long in part because of his overwhelming authority as a guru, which may reflect a larger problem within the culture of yoga. In traditional yogic practice, a guru is a mediator—a translator of sorts—through whom a set of teachings is passed down. Devotion to the guru is meant to symbolize devotion to the teachings, not to the man. But in the Western context gurus become rock stars, and students compete to curry favor with them. This gives gurus significant influence over their students, which is sometimes misused. “I had this idea in me that the guru was supposed to be this all-encompassing everything,” Stern said. “I, along with other people, superimposed these mythologies on top of a human being . . . It was a misunderstanding of what the relationship was supposed to be.

For Rain, apologies from Ashtanga teachers have come too late. She is less interested in public statements and more interested in specific measures that schools can take to change their cultures. Some yoga communities have begun instituting official checks on how teachers are allowed to touch their students, including issuing “consent cards,” which students fill out to indicate whether they are willing to be touched and place at the edge of their mats. Rain wants Ashtanga teachers to pledge to offer free copies of articles about the accusations against Jois at their studios and to post unedited accounts of the allegations on their Web sites. She told me, “I’m offering them a way to make amends by giving the narrative to us.”

Eliza Griswold, a contributing writer covering religion, politics, and the environment, has been writing for The New Yorker since 2003. She won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction for “Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America,” in 2019.