Lowell Institute

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/27/20

The Lowell Institute is a United States educational foundation located in Boston, Massachusetts, providing both free public lectures, and also advanced lectures.[1] It was endowed by a bequest of $250,000 left by John Lowell, Jr.,[2] who died in 1836. The Institute began work in the winter of 1839/40,[3] and an inaugural lecture was given on December 31, 1839, by Edward Everett.[4]

Bequest

Lowell's will set up an endowment with a principal of over $1 million (in 1909), stipulating 10% of its net annual income was to be added back to help it grow. None of the fund was to be invested in a building for the lectures. The trustees of the Boston Athenaeum were made visitors of the fund, but the trustee of the fund is authorized to select his own successor. In naming a successor, the Institute's trustee must always choose in preference to all others some male descendant of Lowell's grandfather, John Lowell, provided there is one who is competent to hold the office of trustee, and of the name of Lowell. The sole trustee so appointed is solely responsible for the entire selection of the lecturers and the subjects of lectures.[citation needed]

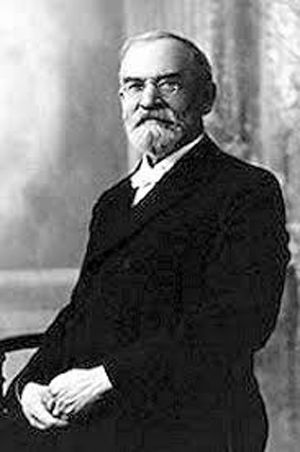

The first trustee was Lowell's cousin, John Amory Lowell, who administered the trust for more than forty years, and was succeeded in 1881 by his son, Augustus Lowell. He in turn was succeeded in 1900 by his son Abbott Lawrence Lowell, who in 1909 also became president of Harvard University.[1]

Activities

Popular lectures

The founder provided for two kinds of lectures, one popular, and the other more advanced. The popular lectures have taken the form of courses usually ranging from half a dozen to a dozen lectures, and covering almost every subject. The payments to the lecturers have always been large, and lectures of many eminent people from America and Europe have been sponsored. A number of books have been published which consist of those lectures or have been based upon them.[1][citation needed]

During the mid-20th century, the Lowell Institute decided to enter the broadcasting business, which led to the creation of the WGBH-FM radio station in 1952, and the WGBH-TV television station in 1955. The WGBH Educational Foundation is now one of the largest producers of public television content and public radio programming in the United States.[citation needed]

As of 2013, the Lowell Institute sponsors an annual series of free public lectures on current scientific topics, under the aegis of the Museum of Science Boston. In addition, the Lowell Institute sponsors the Forum Network,[5] a public media service of the WGBH Educational Foundation which distributes free public lectures over the Internet, from a large number of program partners in and beyond Boston.

Advanced lectures

As to the advanced lectures, the founder seems to have had in view what is now called university extension, and in this he was far ahead of his time. In pursuance of this provision, public instruction of various kinds has been given from time to time by the Institute. The first freehand drawing in Boston was taught there, but was given up when the public schools undertook it. In the same way, a school of practical design was carried on for many years, but finally in 1903 was transferred to the Museum of Fine Arts.[1] Instruction for working men was given at the Wells Memorial Institute until 1908, when the Franklin Foundation took up the work,[1] which resulted in the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology (BFIT). A Teacher's School of Science was maintained in co-operation with the Boston Society of Natural History, later renamed the Museum of Science Boston, which still continues to sponsor professional development courses for secondary school science teachers.

For many years, advanced courses of lectures were given by professors of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and in 1903 these were superseded by an evening "School for Industrial Foremen"[1] sharing classroom and laboratory facilities. Over time, this became known as the Lowell Institute School, remaining on the MIT campus until 1996, when it was transferred to the Northeastern University Engineering School. The Lowell Institute School now is a division of the School of Professional Studies at Northeastern, offering full- and part-time programs leading to certificates, and associate's or bachelor's degrees.[6]

In 1907, under the title of "Collegiate Courses", a number of the elementary courses in Harvard University were offered free to the public under the same conditions of study and examination as in the university.[1] This program eventually became the Harvard University Extension School, now offering hundreds of courses, and certificate and academic degree programs to residents of Greater Boston.

See also

• Lowell Technological Institute

References

1. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lowell Institute". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

2. Elias Nason (1874). A gazetteer of the state of Massachusetts. Boston: B.B. Russell. p. 103.

3. Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Lowell, John, American merchant and philanthropist" . Encyclopedia Americana.

4. Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Lowell Institute" . Encyclopedia Americana.

5. "About the Forum Network". WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

6. "Lowell Institute School". Northeastern University College of Professional Studies. Northeastern University. Retrieved 2012-02-27.

Further reading

• Charles F. Park, A History of the Lowell Institute School, 1903-1928 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931)

• Harriette Knight Smith, The History of the Lowell Institute (Boston: Lamson, Wolffe and Company, 1898)

• Edward Weeks, The Lowells and Their Institute (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966)

• Margaret W. Rossiter. "Benjamin Silliman and the Lowell Institute: The Popularization of Science in Nineteenth-Century America." New England Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Dec., 1971)

• Howard M. Wach. "Expansive Intellect an

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/27/20

The Right Honourable The Lord Brougham and Vaux PC QC FRS

Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

In office: 22 November 1830 – 9 July 1834

Monarch: William IV

Prime Minister: Earl Grey

Preceded by: Lord Lyndhurst

Succeeded by: Lord Lyndhurst

Member of the House of Lords

Lord Temporal

In office: 22 November 1830 – 7 May 1868

Hereditary Peerage

Preceded by: Peerage created

Succeeded by: The 2nd Lord Brougham and Vaux

Member of Parliament for Knaresborough

In office: February 1830 – August 1830

Preceded by: George Tierney

Succeeded by: Henry Cavendish

Member of Parliament for Winchelsea

In office: 1815 – February 1830

Preceded by: William Vane

Succeeded by: John Williams

Member of Parliament for Camelford

In office: 1810 – November 1812

Preceded by: Lord Henry Petty

Succeeded by: Samuel Scott

Personal details

Born: 19 September 1778, Cowgate, Edinburgh

Died: 7 May 1868 (aged 89), Cannes, Second French Empire

Nationality: British

Political party: Whig

Spouse(s) Mary Anne Eden (1785–1865)

Alma mater: University of Edinburgh

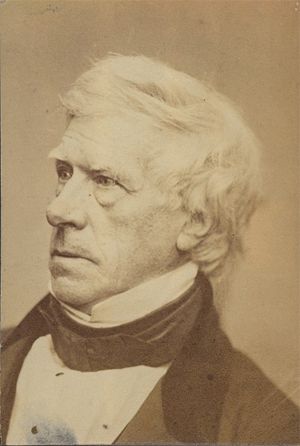

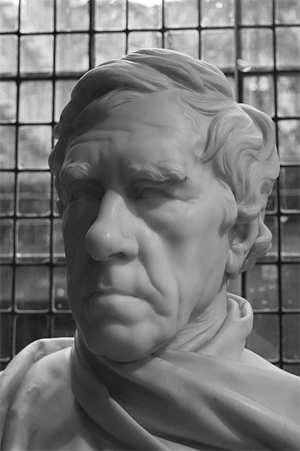

Sir Henry Brougham by John Adams Acton 1867

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, PC, QC, FRS (/ˈbruː(ə)m ... ˈvoʊks/; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor and played a prominent role in passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

Born in Edinburgh, Brougham helped found the Edinburgh Review in 1802 before moving to London, where he qualified as a barrister in 1808. Elected to the House of Commons in 1810 as a Whig, he was Member of Parliament for a number of constituencies until becoming a peer in 1834.

Brougham won popular renown for helping defeat the 1820 Pains and Penalties Bill, an attempt by the widely disliked George IV to annul his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick. He became an advocate of liberal causes including abolition of the slave trade, free trade and parliamentary reform. Appointed Lord Chancellor in 1830, he made a number of reforms intended to speed up legal cases and established the Central Criminal Court. He never regained government office after 1834 and although he played an active role in the House of Lords, he often did so in opposition to his former colleagues.

Education was another area of interest. He helped establish the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and University College London, as well as holding a number of academic posts, including Rector, University of Edinburgh.

In later years he spent much of his time in the French city of Cannes, making it a popular resort for the British upper-classes; he died there in 1868.

Life

Early life

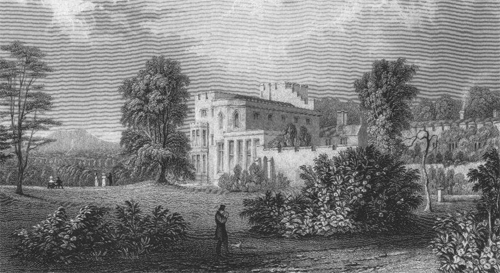

Brougham Hall in 1832.

Brougham was born and grew up in Edinburgh, the eldest son of Henry Brougham (1742–1810), of Brougham Hall in Westmorland, and Eleanora, daughter of Reverend James Syme. The Broughams had been an influential Cumberland family for centuries. Brougham was educated at the Royal High School and the University of Edinburgh, where he chiefly studied natural science and mathematics, but also law. He published several scientific papers through the Royal Society, notably on light and colours and on prisms, and at the age of only 25 was elected a Fellow. However, Brougham chose law as his profession, and was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1800. He practised little in Scotland, and instead entered Lincoln's Inn in 1803. Five years later he was called to the Bar.

Not a wealthy man, Brougham turned to journalism as a means of supporting himself financially through these years. He was one of the founders of the Edinburgh Review and quickly became known as its foremost contributor, with articles on everything from science, politics, colonial policy, literature, poetry, surgery, mathematics and the fine arts.[1] In the early 19th century, Brougham, a follower of Newton, launched anonymous attacks in the Edinburgh Review against Thomas Young's research, which proved light was a wave phenomenon that exhibited interference and diffraction. These attacks slowed acceptance of the truth for a decade, until François Arago and Augustin-Jean Fresnel championed Young's work. Another example of Lord Brougham's scientific incompetence is his attack upon Sir William Herschel (1738–1822), a story is described by Pustiĺnik and Din.[2] Herschel, as Royal Astronomer, found a correlation between the observed number of sunspots and wheat prices.[3] This met with strong and widespread rejection, even ridicule as a "grand absurdity" from Lord Brougham. Herschel had to cancel further publications of these results. Seventy years later, the English economist W. S. Jevons indeed discovered 10–11-year intervals between high wheat prices, in agreement with the 11-year cycle of solar activity discovered at those times. Miroslav Mikulecký, J. Střeštík and V. Choluj[4] found by cross-regression analysis shared periods between climatic temperatures and wheat prices of 15 years for England, 16 years for France and 22 years for Germany. They now believe they have found a direct evidence of a causal connection between the two.

Early career

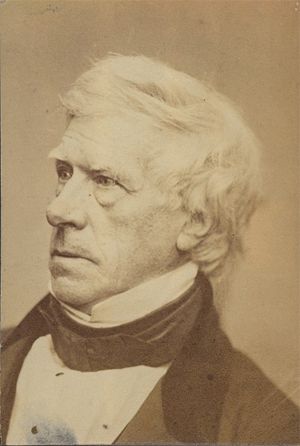

Henry Brougham in 1825

The success of the Edinburgh Review made Brougham a man of mark from his first arrival in London. He quickly became a fixture in London society and gained the friendship of Lord Grey and other leading Whig politicians. In 1806 the Foreign Secretary, Charles James Fox, appointed him secretary to a diplomatic mission to Portugal, led by James St Clair-Erskine, 2nd Earl of Rosslyn, and John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent. The aim of the mission was to counteract the anticipated French invasion of Portugal. During these years he became a close supporter of the movement for the abolition of slavery, a cause to which he was to be passionately devoted for the rest of his life. Despite being a well-known and popular figure, Brougham had to wait before being offered a parliamentary seat to contest. However, in 1810 he was elected for Camelford, a rotten borough controlled by the Duke of Bedford. He quickly gained a reputation in the House of Commons, where he was one of the most frequent speakers, and was regarded by some as a potential future leader of the Whig Party. However, Brougham's career was to take a downturn in 1812, when, standing as one of two Whig candidates for Liverpool, he was heavily defeated. He was to remain out of Parliament until 1816, when he was returned for Winchelsea. He quickly resumed his position as one of the most forceful members of the House of Commons, and worked especially in advocating a programme for the education of the poor and legal reform.[1]

In 1828 he made a six-hour speech, the longest ever made in the House of Commons.[5]

Defence of Queen Caroline

In 1812 Brougham had become one of the chief advisers to Caroline of Brunswick, the estranged wife of George, Prince of Wales, the Prince Regent and future George IV. This was to prove a key development in his life. In April 1820 Caroline, then living abroad, appointed Brougham her Attorney-General. Earlier that year George IV had succeeded to the throne on the death of his long incapacitated father George III. Caroline was brought back to Britain in June for appearances only, but the king immediately began divorce proceedings against her. The Pains and Penalties Bill, aimed at dissolving the marriage and stripping Caroline of her Royal title on the grounds of adultery, was brought before the House of Lords by the Tory government. However, Brougham led a legal team (which also included Thomas Denman) that eloquently defended the Princess. Brougham threatened to introduce evidence of George IV's affairs and his secret marriage to a Catholic woman. This could have potentially thrown the monarchy into chaos, and it was suggested to Brougham that he hold back for the sake of his country. He responded with his now famous speech in the House of Lords:

The speech has since become legendary among defence lawyers for the principle of zealously advocating for one's client.[6] The bill passed, but by the narrow margin of only nine votes. Lord Liverpool, aware of the unpopularity of the bill and afraid that it might be overturned in the House of Commons, then withdrew it. The British public had mainly been on the Princess's side, and the outcome of the trial made Brougham one of the most famous men in the country. His legal practice on the Northern Circuit rose fivefold, although he had to wait until 1827 before being made a King's Counsel.[1]

In 1826 Brougham, along with Wellington, was one of the clients and lovers named in the notorious Memoirs of Harriette Wilson. Before publication, Wilson and publisher John Joseph Stockdale wrote to all those named in the book offering them the opportunity to be excluded from the work in exchange for a cash payment. Brougham paid and secured his anonymity.[7][8]

Lord Chancellor

Brougham remained member of Parliament for Winchelsea until February 1830 when he was returned for Knaresborough. However, he represented Knaresborough only until August the same year, when he became one of four representatives for Yorkshire. His support for the immediate abolition of slavery brought him enthusiastic support in the industrial West Riding. The Reverend Benjamin Godwin of Bradford devised and funded posters that appealed to Yorkshire voters who had supported William Wilberforce to support Brougham as a committed opponent of slavery[9] However, Brougham was adopted as a Whig candidate by only a tiny majority at the nomination meeting: the Whig gentry objecting that he had no connection with agricultural interests, and no connection with the county.[10] Brougham came second in the poll, behind the other Whig candidate; although the liberals of Leeds had placarded the town with claims that one of the Tory candidates supported slavery, this was strenuously denied by him.[11]

In November the Tory government led by the Duke of Wellington fell, and the Whigs came to power under Lord Grey. Brougham joined the government as Lord Chancellor, although his opponents claimed he previously stated he would not accept office under Grey.[12] Brougham refused the post of Attorney General, but accepted that of Lord Chancellor, which he held for four years. On 22 November, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Brougham and Vaux, of Brougham in the County of Westmorland.[1]

Brougham as Lord Chancellor (1830-1834)

The highlights of Brougham's time in government were passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act but he was seen as dangerous, unreliable and arrogant. Charles Greville, who was Clerk of the Privy Council for 35 years, recorded his 'genius and eloquence' was marred by 'unprincipled and execrable judgement.'[13] Although retained when Lord Melbourne succeeded Grey in July 1834, the administration was replaced in November by Sir Robert Peel's Tories. When Melbourne became Prime Minister again in April 1835, he excluded Brougham, claiming his conduct was one of the main reasons for the fall of the previous government; Baron Cottenham became Lord Chancellor in January 1836.[1]

Later life

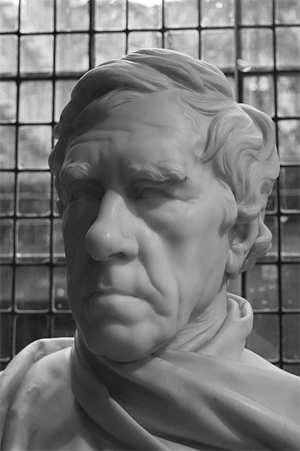

Bust of Henry Brougham in the Playfair Library of Edinburgh University's Old College

The title page of British Constitution (1st ed., 1844), written by Brougham

Brougham was never to hold office again. However, for more than thirty years after his fall he continued to take an active part in the judicial business of the House of Lords, and in its debates, having now turned fiercely against his former political associates, but continuing his efforts on behalf of reform of various kinds. He also devoted much of his time to writing. He had continued to contribute to the Edinburgh Review, the best of his writings being subsequently published as Historical Sketches of Statesmen Who Flourished in the Time of George III.

In 1834 he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1837 Brougham presented a bill for public education, arguing that "it cannot be doubted that some legislative effort must at length be made to remove from this country the opprobrium of having done less for the education of the people than any of the more civilized nations on earth".[14]

In 1838, after news came up of British colonies where emancipation of the slaves was obstructed or where the ex-slaves were being badly treated and discriminated against, Lord Brougham stated in the House of Lords:

Brougham was elected Rector of Marischal College for 1838.[16] He also edited, in collaboration with Sir Charles Bell, William Paley's Natural Theology and published a work on political philosophy and in 1838 he published an edition of his speeches in four volumes. The last of his works was his posthumous Autobiography. In 1857 he was one of the founders of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science and was its president at a number of congresses.

In 1860 Brougham was given by Queen Victoria a second peerage as Baron Brougham and Vaux, of Brougham in the County of Westmorland and of Highhead Castle in the County of Cumberland, with remainder to his youngest brother William Brougham (died 1886). The patent stated that the second peerage was in honour of the great services he had rendered, especially in promoting the abolition of slavery.

Family

Brougham married Mary Spalding (d. 1865), daughter of Thomas Eden and widow of John Spalding, MP, in 1821. They had two daughters, both of whom predeceased their parents, the latter one dying in 1839. Lord Brougham and Vaux died in May 1868 in Cannes, France, aged 89, and was buried in the Cimetière du Grand Jas.[1] The cemetery is up to the present dominated by Brougham's statue, and he is honoured for his major role in building the city of Cannes. His hatchment is in Ninekirks, which was then the parish church of Brougham.

The Barony of 1830 became extinct on his death, while he was succeeded in the Barony of 1860 according to the special remainder by his younger brother William Brougham.

Legacy

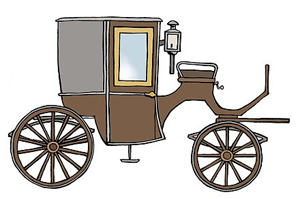

A brougham, of the style built to Lord Brougham's specification

He was the designer of the brougham, a four-wheeled, horse-drawn style of carriage that bears his name.

Brougham's patronage made the renowned French seaside resort of Cannes very popular. He accidentally found the place in 1835, when it was little more than a fishing village on a picturesque coast, and bought there a tract of land and built on it. His choice and his example made it the sanitorium of Europe. Owing to Brougham's influence the beachfront promenade at Nice became known as the Promenade des Anglais (literally, "The Promenade of the English").[17]

A statue of him, inscribed "Lord Brougham", stands at the Cannes waterfront, across from the Palais des festivals et des congrès.

Brougham holds the House of Commons record for non-stop speaking at six hours.[18]

He was present at the trial of the world's first steam powered ship on 14 October 1788 at Dalswinton Loch near Auldgirth, Dumfries and Galloway. William Symington of Wanlockhead built the two-cylindered engine for Patrick Miller of Dalswinton.[19]

Works

Brougham wrote a prodigious number of treatises on science, philosophy, and history. Besides the writings mentioned in this article, he was the author of Dialogues on Instinct; with Analytical View of the Researches on Fossil Osteology, Lives of Statesmen, Philosophers, and Men of Science of the Time of George III, Natural Theology, etc. His last work was an autobiography written in his 84th year and published in 1871.

Brougham's Political Philosophy was included on the Cambridge syllabus for History and Political Philosophy, where it was considered among the major works on the topic along with Aristotle's Politics, François Guizot's Histoire de la civilization en Europe, and Henry Hallam's Constitutional History.[20]

• Henry Brougham Brougham and Vaux (1838). Speeches of Henry Lord Brougham, Upon Questions Relating to Public Rights, Duties, and Interests: With Historical Introductions, and a Critical Dissertation Upon the Eloquence of the Ancients, Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 4 vol. (online: vol. 1, 2, 3, 4)

See also

• March of Intellect

Notes

1. EB (1911).

2. Solar Phys., 2004, vol. 223, pp. 335–56.

3. W. Herschel, Phil.Trans., 1801, vol. 91, p. 265.

4. The Conference "Man in his Terrestrial and Cosmic Environment", Úpice, Czech Republic, 2010, Acad. Sci. Czech Rep., Prague.

5. Kelly, Jon, "The art of the filibuster: How do you talk for 24 hours straight?", BBC News Magazine, 12 December 2012.

6. Uelmen, Gerald. "Lord Brougham's Bromide: Good Lawyers as Bad Citizens", Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, November, 1996.

7. Stockdale, E. (1990). "The unnecessary crisis: The background to the Parliamentary Papers Act 1840". Public Law: 30–49. p. 36.

8. Bourne (1975).

9. Historical Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Bradford, Yorkshire Abolitionist Activity 1787–1865, James Gregory, Plymouth University, History & Art History, Academia.edu. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

10. "Meeting of the Freeholders in the Whig Interest in York". Yorkshire Gazette. 24 July 1830. p. 3.

11. "General Election: Yorkshire Election". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 7 August 1830. p. 3.

12. "NEW WRITS.—CONDUCT OF LORD BROUGHAM". Hansard House of Commons Debates. 1: cc636-49. 23 November 1830. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

13. Greville, Charles (author), Pearce, Edward (editor) (2005). The Diaries of Charles Greville. Pimlico. p. xi. ISBN 978-1844134045.

14. A. Green, Education and State Formation: The Rise of Education Systems in England, France and the USA, Macmillan, 1990

15. Quoted in the "Lawyers on the Edge" website

16. Officers of the Marischal College & University of Aberdeen, 1593-1860.

17. "Cadillac Terms and Definitions A - C". Cadillacdatabase.net. 1996. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

18. "Hansard, 8 May 1989, Column 581". HMSO. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

19. Innes, Brian (1988). The Story of Scotland.. v. 3, part 33, p. 905.

20. Collini, Stefan (1983). That Noble Science of Politics: A Study in Nineteenth-Century Intellectual History. Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

References

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Brougham and Vaux, Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 652–655.

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Brougham And Vaux, Henry, 1st Lord". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. pp. 48–49 – via Wikisource.

External links

• Reeve, Henry (1878). "Henry Brougham" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (9th ed.). pp. 373–381.

• Works by Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at Internet Archive

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Henry Brougham

• All things connected with the Brougham name

• "Archival material relating to Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux". UK National Archives.

• Portraits of Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/27/20

The Right Honourable The Lord Brougham and Vaux PC QC FRS

Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

In office: 22 November 1830 – 9 July 1834

Monarch: William IV

Prime Minister: Earl Grey

Preceded by: Lord Lyndhurst

Succeeded by: Lord Lyndhurst

Member of the House of Lords

Lord Temporal

In office: 22 November 1830 – 7 May 1868

Hereditary Peerage

Preceded by: Peerage created

Succeeded by: The 2nd Lord Brougham and Vaux

Member of Parliament for Knaresborough

In office: February 1830 – August 1830

Preceded by: George Tierney

Succeeded by: Henry Cavendish

Member of Parliament for Winchelsea

In office: 1815 – February 1830

Preceded by: William Vane

Succeeded by: John Williams

Member of Parliament for Camelford

In office: 1810 – November 1812

Preceded by: Lord Henry Petty

Succeeded by: Samuel Scott

Personal details

Born: 19 September 1778, Cowgate, Edinburgh

Died: 7 May 1868 (aged 89), Cannes, Second French Empire

Nationality: British

Political party: Whig

Spouse(s) Mary Anne Eden (1785–1865)

Alma mater: University of Edinburgh

Sir Henry Brougham by John Adams Acton 1867

Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, PC, QC, FRS (/ˈbruː(ə)m ... ˈvoʊks/; 19 September 1778 – 7 May 1868) was a British statesman who became Lord High Chancellor and played a prominent role in passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

Born in Edinburgh, Brougham helped found the Edinburgh Review in 1802 before moving to London, where he qualified as a barrister in 1808. Elected to the House of Commons in 1810 as a Whig, he was Member of Parliament for a number of constituencies until becoming a peer in 1834.

Brougham won popular renown for helping defeat the 1820 Pains and Penalties Bill, an attempt by the widely disliked George IV to annul his marriage to Caroline of Brunswick. He became an advocate of liberal causes including abolition of the slave trade, free trade and parliamentary reform. Appointed Lord Chancellor in 1830, he made a number of reforms intended to speed up legal cases and established the Central Criminal Court. He never regained government office after 1834 and although he played an active role in the House of Lords, he often did so in opposition to his former colleagues.

Education was another area of interest. He helped establish the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and University College London, as well as holding a number of academic posts, including Rector, University of Edinburgh.

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK), was founded in 1826, mainly at the instigation of Lord Brougham,[1] with the object of publishing information to people who were unable to obtain formal teaching, or who preferred self-education. A Whiggish London organisation that published inexpensive texts intended to adapt scientific and similarly high-minded material for the rapidly expanding reading public, it was wound up in 1848.

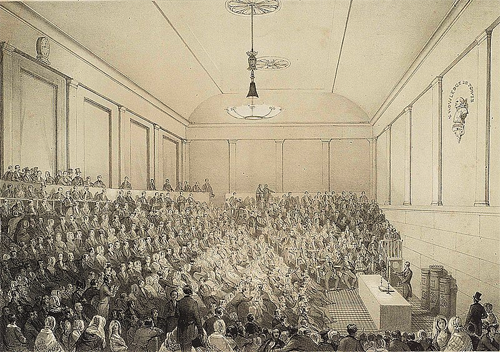

Lecture-Hall of the Greenwich Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, on its opening 15 February 1843

An American group of the same name was founded as part of the Lyceum movement in the United States in 1829. Its Boston branch sponsored lectures by such speakers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, and was active from 1829 to 1947.[2] Henry David Thoreau cites the Society in his essay "Walking," in which he jestingly proposes a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Ignorance.[3]

-- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, by Wikipedia

If Josiah Holbrook had lived to-day, probably he might have been tempted to organize an educational trust, or to corner the market in professors. As it was, he planned a World Lyceum, of which Chancellor Brougham, of England, should be president, and which should have fifty-two vice-presidents, men distinguished in science and in philanthropy, men chosen from every country in the world.

-- Who's Who In the Lyceum, edited by A. Augustus Wright

In later years he spent much of his time in the French city of Cannes, making it a popular resort for the British upper-classes; he died there in 1868.

Life

Early life

Brougham Hall in 1832.

Brougham was born and grew up in Edinburgh, the eldest son of Henry Brougham (1742–1810), of Brougham Hall in Westmorland, and Eleanora, daughter of Reverend James Syme. The Broughams had been an influential Cumberland family for centuries. Brougham was educated at the Royal High School and the University of Edinburgh, where he chiefly studied natural science and mathematics, but also law. He published several scientific papers through the Royal Society, notably on light and colours and on prisms, and at the age of only 25 was elected a Fellow. However, Brougham chose law as his profession, and was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1800. He practised little in Scotland, and instead entered Lincoln's Inn in 1803. Five years later he was called to the Bar.

Not a wealthy man, Brougham turned to journalism as a means of supporting himself financially through these years. He was one of the founders of the Edinburgh Review and quickly became known as its foremost contributor, with articles on everything from science, politics, colonial policy, literature, poetry, surgery, mathematics and the fine arts.[1] In the early 19th century, Brougham, a follower of Newton, launched anonymous attacks in the Edinburgh Review against Thomas Young's research, which proved light was a wave phenomenon that exhibited interference and diffraction. These attacks slowed acceptance of the truth for a decade, until François Arago and Augustin-Jean Fresnel championed Young's work. Another example of Lord Brougham's scientific incompetence is his attack upon Sir William Herschel (1738–1822), a story is described by Pustiĺnik and Din.[2] Herschel, as Royal Astronomer, found a correlation between the observed number of sunspots and wheat prices.[3] This met with strong and widespread rejection, even ridicule as a "grand absurdity" from Lord Brougham. Herschel had to cancel further publications of these results. Seventy years later, the English economist W. S. Jevons indeed discovered 10–11-year intervals between high wheat prices, in agreement with the 11-year cycle of solar activity discovered at those times. Miroslav Mikulecký, J. Střeštík and V. Choluj[4] found by cross-regression analysis shared periods between climatic temperatures and wheat prices of 15 years for England, 16 years for France and 22 years for Germany. They now believe they have found a direct evidence of a causal connection between the two.

Early career

Henry Brougham in 1825

The success of the Edinburgh Review made Brougham a man of mark from his first arrival in London. He quickly became a fixture in London society and gained the friendship of Lord Grey and other leading Whig politicians. In 1806 the Foreign Secretary, Charles James Fox, appointed him secretary to a diplomatic mission to Portugal, led by James St Clair-Erskine, 2nd Earl of Rosslyn, and John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent. The aim of the mission was to counteract the anticipated French invasion of Portugal. During these years he became a close supporter of the movement for the abolition of slavery, a cause to which he was to be passionately devoted for the rest of his life. Despite being a well-known and popular figure, Brougham had to wait before being offered a parliamentary seat to contest. However, in 1810 he was elected for Camelford, a rotten borough controlled by the Duke of Bedford. He quickly gained a reputation in the House of Commons, where he was one of the most frequent speakers, and was regarded by some as a potential future leader of the Whig Party. However, Brougham's career was to take a downturn in 1812, when, standing as one of two Whig candidates for Liverpool, he was heavily defeated. He was to remain out of Parliament until 1816, when he was returned for Winchelsea. He quickly resumed his position as one of the most forceful members of the House of Commons, and worked especially in advocating a programme for the education of the poor and legal reform.[1]

In 1828 he made a six-hour speech, the longest ever made in the House of Commons.[5]

Defence of Queen Caroline

In 1812 Brougham had become one of the chief advisers to Caroline of Brunswick, the estranged wife of George, Prince of Wales, the Prince Regent and future George IV. This was to prove a key development in his life. In April 1820 Caroline, then living abroad, appointed Brougham her Attorney-General. Earlier that year George IV had succeeded to the throne on the death of his long incapacitated father George III. Caroline was brought back to Britain in June for appearances only, but the king immediately began divorce proceedings against her. The Pains and Penalties Bill, aimed at dissolving the marriage and stripping Caroline of her Royal title on the grounds of adultery, was brought before the House of Lords by the Tory government. However, Brougham led a legal team (which also included Thomas Denman) that eloquently defended the Princess. Brougham threatened to introduce evidence of George IV's affairs and his secret marriage to a Catholic woman. This could have potentially thrown the monarchy into chaos, and it was suggested to Brougham that he hold back for the sake of his country. He responded with his now famous speech in the House of Lords:

"An advocate, in the discharge of his duty, knows but one person in all the world, and that person is his client. To save that client by all means and expedients, and at all hazards and costs to other persons, and amongst them, to himself, is his first and only duty; and in performing this duty he must not regard the alarm, the torments, the destruction which he may bring upon others. Separating the duty of a patriot from that of an advocate, he must go on reckless of consequences, though it should be his unhappy fate to involve his country in confusion."

The speech has since become legendary among defence lawyers for the principle of zealously advocating for one's client.[6] The bill passed, but by the narrow margin of only nine votes. Lord Liverpool, aware of the unpopularity of the bill and afraid that it might be overturned in the House of Commons, then withdrew it. The British public had mainly been on the Princess's side, and the outcome of the trial made Brougham one of the most famous men in the country. His legal practice on the Northern Circuit rose fivefold, although he had to wait until 1827 before being made a King's Counsel.[1]

In 1826 Brougham, along with Wellington, was one of the clients and lovers named in the notorious Memoirs of Harriette Wilson. Before publication, Wilson and publisher John Joseph Stockdale wrote to all those named in the book offering them the opportunity to be excluded from the work in exchange for a cash payment. Brougham paid and secured his anonymity.[7][8]

Lord Chancellor

NO SLAVERY!

ELECTORS OF THE COUNTY OF YORK

You honourably distinguished yourselves

In the ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE

by your zealous support of

WILLIAM WILBERFORCE

Who can be more worthy of your choice as a

REPRESENTATIVE FOR THE COUNTY

the enlightened friend and champion of Negro Freedom

HENRY BROUGHAM

by returning him

YOU WILL DO AN HONOUR TO THE COUNTY

and

A SERVICE TO HUMANITY[9]

Brougham remained member of Parliament for Winchelsea until February 1830 when he was returned for Knaresborough. However, he represented Knaresborough only until August the same year, when he became one of four representatives for Yorkshire. His support for the immediate abolition of slavery brought him enthusiastic support in the industrial West Riding. The Reverend Benjamin Godwin of Bradford devised and funded posters that appealed to Yorkshire voters who had supported William Wilberforce to support Brougham as a committed opponent of slavery[9] However, Brougham was adopted as a Whig candidate by only a tiny majority at the nomination meeting: the Whig gentry objecting that he had no connection with agricultural interests, and no connection with the county.[10] Brougham came second in the poll, behind the other Whig candidate; although the liberals of Leeds had placarded the town with claims that one of the Tory candidates supported slavery, this was strenuously denied by him.[11]

In November the Tory government led by the Duke of Wellington fell, and the Whigs came to power under Lord Grey. Brougham joined the government as Lord Chancellor, although his opponents claimed he previously stated he would not accept office under Grey.[12] Brougham refused the post of Attorney General, but accepted that of Lord Chancellor, which he held for four years. On 22 November, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Brougham and Vaux, of Brougham in the County of Westmorland.[1]

Brougham as Lord Chancellor (1830-1834)

The highlights of Brougham's time in government were passing the 1832 Reform Act and 1833 Slavery Abolition Act but he was seen as dangerous, unreliable and arrogant. Charles Greville, who was Clerk of the Privy Council for 35 years, recorded his 'genius and eloquence' was marred by 'unprincipled and execrable judgement.'[13] Although retained when Lord Melbourne succeeded Grey in July 1834, the administration was replaced in November by Sir Robert Peel's Tories. When Melbourne became Prime Minister again in April 1835, he excluded Brougham, claiming his conduct was one of the main reasons for the fall of the previous government; Baron Cottenham became Lord Chancellor in January 1836.[1]

Later life

Bust of Henry Brougham in the Playfair Library of Edinburgh University's Old College

The title page of British Constitution (1st ed., 1844), written by Brougham

Brougham was never to hold office again. However, for more than thirty years after his fall he continued to take an active part in the judicial business of the House of Lords, and in its debates, having now turned fiercely against his former political associates, but continuing his efforts on behalf of reform of various kinds. He also devoted much of his time to writing. He had continued to contribute to the Edinburgh Review, the best of his writings being subsequently published as Historical Sketches of Statesmen Who Flourished in the Time of George III.

In 1834 he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 1837 Brougham presented a bill for public education, arguing that "it cannot be doubted that some legislative effort must at length be made to remove from this country the opprobrium of having done less for the education of the people than any of the more civilized nations on earth".[14]

In 1838, after news came up of British colonies where emancipation of the slaves was obstructed or where the ex-slaves were being badly treated and discriminated against, Lord Brougham stated in the House of Lords:

"The slave … is as fit for his freedom as any English peasant, aye, or any Lord whom I now address. I demand his rights; I demand his liberty without stint… . I demand that your brother be no longer trampled upon as your slave!"[15]

Brougham was elected Rector of Marischal College for 1838.[16] He also edited, in collaboration with Sir Charles Bell, William Paley's Natural Theology and published a work on political philosophy and in 1838 he published an edition of his speeches in four volumes. The last of his works was his posthumous Autobiography. In 1857 he was one of the founders of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science and was its president at a number of congresses.

In 1860 Brougham was given by Queen Victoria a second peerage as Baron Brougham and Vaux, of Brougham in the County of Westmorland and of Highhead Castle in the County of Cumberland, with remainder to his youngest brother William Brougham (died 1886). The patent stated that the second peerage was in honour of the great services he had rendered, especially in promoting the abolition of slavery.

Family

Brougham married Mary Spalding (d. 1865), daughter of Thomas Eden and widow of John Spalding, MP, in 1821. They had two daughters, both of whom predeceased their parents, the latter one dying in 1839. Lord Brougham and Vaux died in May 1868 in Cannes, France, aged 89, and was buried in the Cimetière du Grand Jas.[1] The cemetery is up to the present dominated by Brougham's statue, and he is honoured for his major role in building the city of Cannes. His hatchment is in Ninekirks, which was then the parish church of Brougham.

The Barony of 1830 became extinct on his death, while he was succeeded in the Barony of 1860 according to the special remainder by his younger brother William Brougham.

Legacy

A brougham, of the style built to Lord Brougham's specification

He was the designer of the brougham, a four-wheeled, horse-drawn style of carriage that bears his name.

Brougham

The term "Brougham" has been used by every single American car manufacturer as well as a few foreign ones to designate a car model or trim package with richly appointed features. It refers to the elegant "Brougham" carriage popular in the 19th century. That carriage was originally built to the specifications of and named for Lord Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, a British statesman who became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain. Brother Brougham was a member of Canongate Kilwinning Lodge 2 of Edinburgh Scotland.

-- Freemasons: Tales from the Craft, by Steven L. Harrison

About Lodge Canongate Kilwinning

Lodge Canongate Kilwinning was Chartered in 1677 in the Canongate, an area of Edinburgh. It was the first known example in the world of a Lodge being granted a charter by an existing Lodge, in this case The Lodge of Kilwinning (latterly known as Mother Kilwinning). The minutes of that Lodge refer to the granting of a charter to Lodge Canongate Kilwinning on 20 December 1677.

On the 6th December 1677 Masons from the Canongate wrote to Mother Kilwinning by petition requesting permission to enter and pass persons in its name and on its behalf. This permission in the form of a Charter was duly granted on the 20th December 1677. The Canongate was home to a great number of the nobility and prosperous merchants; this was reflected in the membership of the Lodge at that time. (See About The Canongate) An indication of its rise was the fact that at this time, it was able to have built for its own use, a very fine building known as the Chapel of St John. This makes it the oldest purpose built Masonic meeting room in the world. This Masonic meeting room is very much as it was built, and is still used by the Lodge for its meetings to this day. (See About The Chapel of St John)

Reflecting the increase in interest in Freemasonry at the time, 1735 saw the initial attempts to establish a Grand Lodge of Scotland. The initiative in forming Grand Lodge was taken by Lodge Canongate Kilwinning and this was duly established in 1736. One of our members, William St. Clair of Roslin (Rosslyn), became the first Grand Master of The Grand Lodge of Scotland and his portrait adorns the wall of The Chapel of St John to this day. The earliest information of the election of a Grand Master for Scotland is here transcribed in full from the minute of the Lodge dated 29th September 1735:-” Cannongate, the 29th Septemr. 1735. 5735-

“The Lodge having mett according to adjournment being duely form’d, this being a quarterly meeting, continued the Committee for the Laws, admitted William Montgomery, Master Mason, who pay’d as usual, and appointed David Home, William Robertson, Thomas Trotter, Robert Blissett, William Montgomery, George Crawford, & such other Members as think fitt to attend, as a Committee for framing proposals to be lay’d before the several Lodges in order to the chusing a Grand Master for Scotland, the Committee to meet to-morrow’s night at 6 o’ th’ clock, & to report against Wednesday’, to which time the Lodge stands adjourned.”

During the eighteenth century, Edinburgh was at the centre of the world of philosophical thought as the Scottish Enlightenment gathered pace. Lodge Canongate Kilwinning attracted a large number of men of learning, many of whom are recognised Enlightenment figures through their published works.

Perhaps the most famous is Robert Burns, who affiliated to Lodge Canongate Kilwinning on 1st February 1787, as recorded in our minutes (See Robert Burns and The Lodge). While this is a well reported fact by biographers, what is less known about is the large number of members of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning who had a significant influence on encouraging Burns to come to Edinburgh and publish a second edition. (See The Inauguration Painting Who’s Who)

Throughout the years, Lodge Canongate Kilwinning has played an important part in Scottish Freemasonry, and continues to do so. The Immediate Past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, Brother Sir Archibald Donald Orr Ewing was initiated into Freemasonry in Lodge Canongate Kilwinning in 1972. The Chapel of St John has become known around the world through the painting “The Inauguration of Robert Burns as Poet Laureate of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, 1st February 1787”. This painting has doubtless caused controversy, much of which was instigated and exacerbated by David Murray Lyon, Past Grand Secretary when he embarked oh his “History of The Lodge of Edinburgh” circa 1873 (To find out more see “About The Inauguration Painting”)

The Lodge continues to meet eight times a year in The Chapel of St John, and practises Freemasonry under The Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland. Our membership has seen a steady increase over the past decade, and is drawn from all ages (from students in their early twenties, to a number of nonagenarians) and walks of life.

It is impossible not to be moved by the atmosphere that exists in the Chapel of St John and the spirit of many famous members pervades the place. After the more formal part of the meeting, we retire to the Refectory for a meal and refreshments. The meetings and refreshment have a timeless quality and the following description of the meeting is as applicable today as it was when it was written: “Having spent the evening in a very social, affectionate and Brotherly manner as the meetings of this Lodge always have been it was adjourned till the next monthly meeting” Minute Book of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning 1st February 1787, the night on which Robert Burns was assumed a member.

The earliest Minute book of the Lodge in preservation dates from 1735. Reading through the sometimes faded and blotted paper, a fascinating story of a central part of Scotland’s history emerges. Robert Burns was perhaps the most famous of our members who graced The Chapel of St John but there are many others whose stories deserve to be retold from the perspective of their membership of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning. Over the coming months we hope to bring you some of those stories, so please bookmark this site and return for regular updates.

***

About the Canongate

Edinburgh initially grew as a result of the natural defences of a volcanic outcrop of rock on which Edinburgh Castle was built. On three sides there are sheer cliffs in excess of a hundred feet, so the only approach is via a long sloping hill which lies to the east of the Castle which provided the only possible direction of expansion as the town grew.

King David I of Scotland, while hunting in the forest of Drumsheugh, in the immediate vicinity of Edinburgh in 1128 was attacked by an enraged stag, which unhorsed him and threatened him with certain death. He raised his hands to protect himself but saw a cross between its antlers.

On seeing the cross, the King took courage and he saw the stag off. In gratitude for his miraculous deliverance, the king founded the monastery of the Holy Cross, and richly endowed it. This was the Augustinian Holyrood Abbey, located about one mile east of the castle, and the ruins of the Abbey are still in existence today.

King David I. granted to the canons of Holyroodhouse the privilege of erecting a burgh, between the town of Edinburgh and church of Holyroodhouse. Thereafter, the Stag, with a cross between its antlers, became the Coat of Arms of Canongate and may still be seen on many buildings in the area. It also forms part of the Lodge crest.

The name Canongate derives from the time when the canons of Holyrood Abbey would walk to their former residence in Edinburgh Castle, the area closest to Holyrood was known as the Canons’ Gait or Walk. The burgesses had “a power to elect annually at Michaelmas two or three bailiffs, and a treasurer, with a proper number of officers for the administration of justice,” and the said burgesses were likewise empowered to hold courts both civil and criminal.

When the city of Edinburgh was enclosed by walls in the middle ages, the wall only extended as far as St Mary Street, so the Canongate was outside the city of Edinburgh.

The reigning Sovereign often preferred to stay at the Abbey, rather than in the Castle, and in 1501 James IV (1488-1513) built a Palace for himself and his bride, Margaret Tudor (sister of Henry VIII). When the New Town of Edinburgh was built in the eighteenth century, the Canongate became somewhat rundown, as the nobility moved to the more fashionable streets to the north.

This decline continued and in the 1930s, there are reports of six and seven living in one room, each room of the house being the home of a family and twenty- four people sharing one lavatory and one water tap. There were as many as one hundred and fifty nine people living in one house on St John St. (The Kirk in the Canongate by Rev Ronald Selby Wright, Minister of Canongate Kirk from 1937-1977 and a member of Lodge Canongate Kilwinning).

When Scotland voted for a devolved Parliament in 1997, a site bordering the Canongate at Holyrood was chosen to build the award winning Parliament Building which together with a very busy tourist trade has seen the resurgence of the area again.

The picture to the left shows the foot (most easterly point) of the Canongate, with the edge of the New Parliament Building on the right, the Palace of Holyrood House, the official Edinburgh residence of the Reigning Monarch, and the remains of Holyrood Abbey to the left.

There is an atmosphere in the Canongate which is hard to describe. Great events took place in the area; many famous people rode or walked up the Canongate to Edinburgh. Perhaps it is best left to others to describe that mood. Here are a few examples from more famous writers who also felt the strong influence of the Canongate:“Sic itur ad astra, (This is the path to heaven)” Such is the ancient motto attached to the armorial bearings of the Canongate, and which is inscribed, with greater or less propriety, upon all the public buildings, from the church to the pillory, in the ancient quarter of Edinburgh, which bears, or rather once bore, the same relation to the Good Town that Westminster does to London, being still possessed of the palace of the sovereign, as it formerly was dignified by the residence of the principal nobility and gentry.

-- Sir Walter ScottOur claims in behalf of the Canongate are not the slightest or least interesting. We will not match ourselves except with our equals and with our equals in age only, for in dignity we admit of none. We boast being of the Court end of the town, possessing the Palace and the sepulchral remains of ancient Monarchs, and that we have the power to excite, in a degree unknown to the less honoured quarters of the city, the dark and solemn recollections of the ancient grandeur, which occupied the precincts of our venerable Abbey from the time of St David, till her deserted halls were once more glad, and her long silent echoes awakened, by the visit of our present Sovereign.

-- Sir Walter ScottThe very Canongate has a sort of sacredness in it.

-- Lord CockburnWho could ever hope to tell all its story, or the story of a single wynd in it?

-- JM BarrieThe way (to Holyrood) lies straight down the only great street of the Old Town, a street by far the most impressive in its character of any I have ever seen in Britain.

-- JG Lockhart.You did not shape the mountains, nor shape the shores; and the historical houses of your Canongate, and the broad battlements of your Castle, reflect honour upon you only through your ancestors.

-- John RuskinThe Palace of Holyrood-House stands on your left as you enter the Canongate. This is a street continued hence to the gate called Netherbow, which is now taken away; so that there is no interruption for a long mile, from the bottom to the top of the hill, on which the castle stands in a most imperial situation ….undoubtedly one of the noblest streets in Europe.

-- Tobias SmollettThe pilgrim strolls away into the Canongate… and still the storied figures of history walk by his side or come to meet him at every close and wynd. John Knox, Robert Burns, Tobias Smollett, David Hume, Dugald Stuart, John Wilson, Hugh Miller-Gray, led onward by the blythe and gracious Duchess of Queensberry, and Dr Johnson, escorted by the affectionate and faithful James Boswell, the best biographer that ever lived,- these and many more, the lettered worthies of long ago, throng into this haunted street and glorify it with the rekindled splendours of other days. You cannot be lonely here. This is it that makes the place so eloquent and so precious.

-- William Winter.Down the street, too, often limped a little boy, Walter Scott by name, destined in after years to write its Chronicles. The Canongate once seen is never to be forgotten. The visitor starts a ghost with every step……. On the intellectual man, living or working in Edinburgh, the light comes through the stained window of the past. Today’s event is not raw or brusque; it comes draped in romantic colour, hued with ancient gules and or.

-- Alexander Smith

Hopefully, these quotations give a flavour of the magical area of Edinburgh which has been home to Lodge Canongate Kilwinning since before the granting of its Charter in 1677.

-- About Lodge Canongate Kilwinning, by Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2

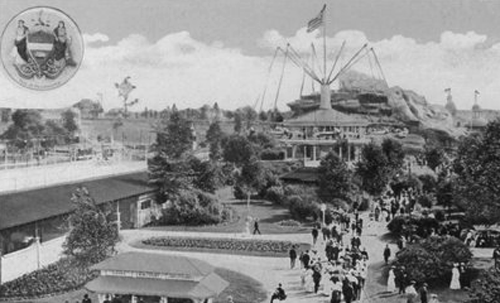

Brougham's patronage made the renowned French seaside resort of Cannes very popular. He accidentally found the place in 1835, when it was little more than a fishing village on a picturesque coast, and bought there a tract of land and built on it. His choice and his example made it the sanitorium of Europe. Owing to Brougham's influence the beachfront promenade at Nice became known as the Promenade des Anglais (literally, "The Promenade of the English").[17]

A statue of him, inscribed "Lord Brougham", stands at the Cannes waterfront, across from the Palais des festivals et des congrès.

Brougham holds the House of Commons record for non-stop speaking at six hours.[18]

He was present at the trial of the world's first steam powered ship on 14 October 1788 at Dalswinton Loch near Auldgirth, Dumfries and Galloway. William Symington of Wanlockhead built the two-cylindered engine for Patrick Miller of Dalswinton.[19]

Works

Brougham wrote a prodigious number of treatises on science, philosophy, and history. Besides the writings mentioned in this article, he was the author of Dialogues on Instinct; with Analytical View of the Researches on Fossil Osteology, Lives of Statesmen, Philosophers, and Men of Science of the Time of George III, Natural Theology, etc. His last work was an autobiography written in his 84th year and published in 1871.

Brougham's Political Philosophy was included on the Cambridge syllabus for History and Political Philosophy, where it was considered among the major works on the topic along with Aristotle's Politics, François Guizot's Histoire de la civilization en Europe, and Henry Hallam's Constitutional History.[20]

• Henry Brougham Brougham and Vaux (1838). Speeches of Henry Lord Brougham, Upon Questions Relating to Public Rights, Duties, and Interests: With Historical Introductions, and a Critical Dissertation Upon the Eloquence of the Ancients, Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 4 vol. (online: vol. 1, 2, 3, 4)

See also

• March of Intellect

Notes

1. EB (1911).

2. Solar Phys., 2004, vol. 223, pp. 335–56.

3. W. Herschel, Phil.Trans., 1801, vol. 91, p. 265.

4. The Conference "Man in his Terrestrial and Cosmic Environment", Úpice, Czech Republic, 2010, Acad. Sci. Czech Rep., Prague.

5. Kelly, Jon, "The art of the filibuster: How do you talk for 24 hours straight?", BBC News Magazine, 12 December 2012.

6. Uelmen, Gerald. "Lord Brougham's Bromide: Good Lawyers as Bad Citizens", Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, November, 1996.

7. Stockdale, E. (1990). "The unnecessary crisis: The background to the Parliamentary Papers Act 1840". Public Law: 30–49. p. 36.

8. Bourne (1975).

9. Historical Perspectives on the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Bradford, Yorkshire Abolitionist Activity 1787–1865, James Gregory, Plymouth University, History & Art History, Academia.edu. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

10. "Meeting of the Freeholders in the Whig Interest in York". Yorkshire Gazette. 24 July 1830. p. 3.

11. "General Election: Yorkshire Election". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 7 August 1830. p. 3.

12. "NEW WRITS.—CONDUCT OF LORD BROUGHAM". Hansard House of Commons Debates. 1: cc636-49. 23 November 1830. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

13. Greville, Charles (author), Pearce, Edward (editor) (2005). The Diaries of Charles Greville. Pimlico. p. xi. ISBN 978-1844134045.

14. A. Green, Education and State Formation: The Rise of Education Systems in England, France and the USA, Macmillan, 1990

15. Quoted in the "Lawyers on the Edge" website

16. Officers of the Marischal College & University of Aberdeen, 1593-1860.

17. "Cadillac Terms and Definitions A - C". Cadillacdatabase.net. 1996. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

18. "Hansard, 8 May 1989, Column 581". HMSO. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

19. Innes, Brian (1988). The Story of Scotland.. v. 3, part 33, p. 905.

20. Collini, Stefan (1983). That Noble Science of Politics: A Study in Nineteenth-Century Intellectual History. Cambridge University Press. p. 346.

References

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Brougham and Vaux, Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron". Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 652–655.

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Brougham And Vaux, Henry, 1st Lord". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. pp. 48–49 – via Wikisource.

External links

• Reeve, Henry (1878). "Henry Brougham" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (9th ed.). pp. 373–381.

• Works by Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at Internet Archive

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Henry Brougham

• All things connected with the Brougham name

• "Archival material relating to Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux". UK National Archives.

• Portraits of Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

The Salem Lyceum Society

by salemweb.com

Accessed: 2/28/20

It is unlikely that any American movement has permeated the national culture as quickly and thoroughly as the lyceums in the mid-nineteenth century.

Lyceums were the brainchild of Joshua [Josiah] Holbrook, who borrowed the concept from the Mechanics Institutes he had encountered in England. Holbrook started the first lyceum in Milbury, Mass., in 1828 and before long there were 100 similar societies sprinkled throughout New England. By 1834, the number of lyceums in America had grown to 3,000.

The Lyceum Hall on Church Street, Salem

One of those lyceums was organized in Salem in January 1830. The expressed purpose of the Salem Lyceum Society was to provide "mutual education and rational entertainment" for both its membership and the general public through a biannual course of lectures, debates and dramatic readings.

While no debates were actually ever held, there were, over the next 60 years, more than 1,000 lectures on such varied themes as literature, science, politics and government, and even phrenology. The inaugural lecture, "Advantages of Knowledge," was given in February by Society President Daniel White, and followed by talks by Society Treasurer Francis Peabody, and Society Vice President Stephen C. Phillips and others. James Flint concluded this first course with three lectures on anatomy and health.

These early lectures were held in either the former Methodist Church on Sewall Street or the Universalist Church on Rust Street. In 1831, the Salem Lyceum Society bought land and erected its own building on Church Street at a cost of approximately $4,000. The new hall could accommodate 700 patrons in amphitheater-style seating and was decorated with images of Cicero, Demosthenes and other great orators of bygone days.

Lectures were held on Tuesday evenings. Admission was $1 for men and 75 cents for women, who had to be "introduced" by a male to gain entrance. Most of the early speakers, including John Pickering, Henry K. Oliver and Charles Upham, were Lyceum members and spoke gratis or for a minimal fee. The combination of unpaid lecturers and sellout crowds (most talks had to be repeated on Wednesday) enabled the Society to pay off the outstanding mortgage on its new hall in a short time.

Once free of its overhead, The Salem Lyceum Society could afford to bring in outside speakers and, over the next half century, many of the great intellects of New England found their way to the Church Street stage. Richard Henry Dana Jr. spoke on "The Reality of the Sea" and "The Importance of Cultivating the Affections," while former United States President John Quincy Adams related themes of "Faith and Government". Oliver Wendall Holmes discoursed on "Lyceums and Lyceum Lectures;" abolitionist Frederic Douglas, on "Assassination and its Lessons" shortly after President Lincoln's murder; and James Russell Lowell, on "Dante".

Salem's most famous personage, Nathaniel Hawthorne, never spoke at the Lyceum himself but, during his stint as corresponding secretary for the 1848-9 lecture series, he enlisted as lecturers many of his famous associates. Hawthorne's roster of speakers included his brother-in-law, Horace Mann, his Concord friends, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his publisher, James T. Fields. Hawthorne was also responsible for the largest fee ever paid to a guest lecturer: Daniel Webster walked away with a cool $100 for his talk on "The History of the Constitution of the United States."

The record for the most appearances unquestionably belonged to Emerson, who spoke nearly 30 times in the Salem Lyceum alone. Like many other authors of the era, Emerson used Lyceum audiences to gauge the popularity of an essay or book before going to the expense of publishing it.

Over the life of The Salem Lyceum, only a half-dozen women were invited to appear on the Church Street stage. The best known was British actress Fanny Kemble, whose dramatic reading of Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream", was a highlight of the 1849-50 course of lectures.

One of Kemble's fellow female presenters bore the appropriately Victorian name of Laura F. Dainty.

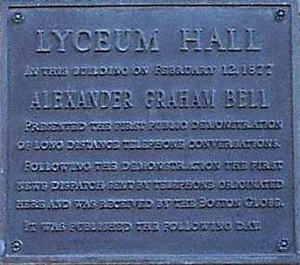

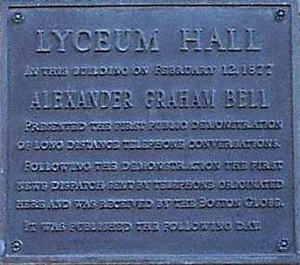

February 12, 1877, Alexander Graham Bell at the Lyceum Hall - first public demonstration of long distance telephone conversation.

Ironically, the most significant event to take place in the Lyceum Hall - Alexander Graham Bell's first public demonstration of the telephone on February 12, 1877 - was sponsored not by the Salem Lyceum Society, but by the Essex Institute.

But in the lyceum tradition, the event proved so successful and popular that it had to be repeated a few weeks later.

by salemweb.com

Accessed: 2/28/20

It is unlikely that any American movement has permeated the national culture as quickly and thoroughly as the lyceums in the mid-nineteenth century.

Lyceums were the brainchild of Joshua [Josiah] Holbrook, who borrowed the concept from the Mechanics Institutes he had encountered in England. Holbrook started the first lyceum in Milbury, Mass., in 1828 and before long there were 100 similar societies sprinkled throughout New England. By 1834, the number of lyceums in America had grown to 3,000.

The Lyceum Hall on Church Street, Salem

One of those lyceums was organized in Salem in January 1830. The expressed purpose of the Salem Lyceum Society was to provide "mutual education and rational entertainment" for both its membership and the general public through a biannual course of lectures, debates and dramatic readings.

While no debates were actually ever held, there were, over the next 60 years, more than 1,000 lectures on such varied themes as literature, science, politics and government, and even phrenology. The inaugural lecture, "Advantages of Knowledge," was given in February by Society President Daniel White, and followed by talks by Society Treasurer Francis Peabody, and Society Vice President Stephen C. Phillips and others. James Flint concluded this first course with three lectures on anatomy and health.

These early lectures were held in either the former Methodist Church on Sewall Street or the Universalist Church on Rust Street. In 1831, the Salem Lyceum Society bought land and erected its own building on Church Street at a cost of approximately $4,000. The new hall could accommodate 700 patrons in amphitheater-style seating and was decorated with images of Cicero, Demosthenes and other great orators of bygone days.

Lectures were held on Tuesday evenings. Admission was $1 for men and 75 cents for women, who had to be "introduced" by a male to gain entrance. Most of the early speakers, including John Pickering, Henry K. Oliver and Charles Upham, were Lyceum members and spoke gratis or for a minimal fee. The combination of unpaid lecturers and sellout crowds (most talks had to be repeated on Wednesday) enabled the Society to pay off the outstanding mortgage on its new hall in a short time.

Once free of its overhead, The Salem Lyceum Society could afford to bring in outside speakers and, over the next half century, many of the great intellects of New England found their way to the Church Street stage. Richard Henry Dana Jr. spoke on "The Reality of the Sea" and "The Importance of Cultivating the Affections," while former United States President John Quincy Adams related themes of "Faith and Government". Oliver Wendall Holmes discoursed on "Lyceums and Lyceum Lectures;" abolitionist Frederic Douglas, on "Assassination and its Lessons" shortly after President Lincoln's murder; and James Russell Lowell, on "Dante".

Salem's most famous personage, Nathaniel Hawthorne, never spoke at the Lyceum himself but, during his stint as corresponding secretary for the 1848-9 lecture series, he enlisted as lecturers many of his famous associates. Hawthorne's roster of speakers included his brother-in-law, Horace Mann, his Concord friends, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and his publisher, James T. Fields. Hawthorne was also responsible for the largest fee ever paid to a guest lecturer: Daniel Webster walked away with a cool $100 for his talk on "The History of the Constitution of the United States."

The record for the most appearances unquestionably belonged to Emerson, who spoke nearly 30 times in the Salem Lyceum alone. Like many other authors of the era, Emerson used Lyceum audiences to gauge the popularity of an essay or book before going to the expense of publishing it.

Over the life of The Salem Lyceum, only a half-dozen women were invited to appear on the Church Street stage. The best known was British actress Fanny Kemble, whose dramatic reading of Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream", was a highlight of the 1849-50 course of lectures.

One of Kemble's fellow female presenters bore the appropriately Victorian name of Laura F. Dainty.

February 12, 1877, Alexander Graham Bell at the Lyceum Hall - first public demonstration of long distance telephone conversation.

Ironically, the most significant event to take place in the Lyceum Hall - Alexander Graham Bell's first public demonstration of the telephone on February 12, 1877 - was sponsored not by the Salem Lyceum Society, but by the Essex Institute.

But in the lyceum tradition, the event proved so successful and popular that it had to be repeated a few weeks later.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

The Passing of a Lyceum Father: Henry L. Slayton, Founder of the Slayton Bureau, Passes On. A Life Rich in Achievement, an Example for All Who Follow

by The Lyceumite & Talent, Volume 4

June, 1910

Of that first lyceum triumvirate – Redpath, Major Pond and Henry Slayton, the last one has just answered the call of death. Henry L. Slayton, founder of the Slayton Lyceum Bureau, and one of the fathers of the lyceum, as we know it today, died at the residence of S.S. Brown, at 6321 Kimbark Ave., Chicago, June 10. He had returned from his long sojourn in Florida but a few days. For years he had been in poor health. Coming into the unpropitious weather of the north last month he took a severe cold which aggravated his old troubles. Death came after a very short illness.

The funeral was held at the Bowen home on the afternoon of the 13th, a short service conducted by Dr. F.W. Gunsaulus. The burial was at Oakwood Cemetery. In the cemetery chapel the Dunbar Company sang “God Is Love,” and President Ott made an address on behalf of the I.L.A. [International Lyceum Association], which association laid a floral tribute on the casket of the dead man. There were a number of lyceum people present, mindful of the great work he had done.

Henry Lake Slayton was born at Woodstock, Vt., May 29, 1841. After he was graduated from college he studied law at the Albany Law School, where he was a classmate of the late President McKinley. When the war broke out he enlisted and became a lieutenant in a colored regiment of volunteers. Before being mustered out he was brevetted captain. He was offered a captaincy in the regular army, but declined. Previous to his war experience he had been a drill master, in which he obtained much distinction. His next activity was as organizer of free schools in the state of Texas, during which time he organized over fifty such schools in the Lone Star state, riding a circuit of over 10,000 miles, with headquarters at Corsicana, where he also conducted a newspaper.

He came to Chicago and had set up a law office when the great fire of 1871 swept him into the general loss. In 1873 he was married to Mina F. Gregory, daughter of Hon. and Mrs. John Gregory of Northfield, Vt., who was later known as Mina G. Slayton, elocutionist and reader. She became a general favorite, her only distinguished rival being Mrs. Scott Siddons. It was a battle of the beauties. Mr. Slayton managed his wife’s business from his law office, which was in reality the incipient Slayton Bureau, dating from 1874. The success of the bureau was emphatic, and it soon became recognized as a dominant lyceum factor. It was not long until the management of Robert G. Ingersoll’s platform business was offered this bureau, which had he accepted would have meant Slayton’s retirement from the lyceum field. It was about this time that a young orator came forward to answer Ingersoll. Mr. Slayton took his management – he was George R. Wendling – and they were associated for years.

It was in 1879 that Mr. Slayton took a partner, J. Allen Whyte, to whom we are indebted for some of the early bureau history. Mr. Whyte, who is now in the real estate and promotion business in Chicago, was successively agent, manager and partner in the bureau until 1886. In 1888 the bureau was incorporated and Byron G. Fuller purchased an interest. He retired in 1892 and Mr. Whyte again entered the company, continuing with it until 1900, when Mr. Slayton’s son Wendell P. became a member of the company. Several years later Charles L. Wagner became secretary and the bureau continued to be a strong factor in the lyceum. It was united with the Redpath less than two years ago, Mr. Slayton’s poor health urging his retirement. He lived quietly at his new home in St. Petersburg, Florida, on until his north trip with its fatal termination.

Two Associates Pay Him Tribute

Henry Slayton’s work is well done. The tributes come from far and near. He was the pioneer developer of the western field. He had the true lyceum vision. He ran a great lecture course in the city of Chicago at one time. He discovered many of the famous platformists and managed scores of the famous ones. It is not generally known that he was not only a lawyer and a teacher but also a newspaper writer and a lecturer himself.

Says his partner, Mr. Whyte: “From the day we first met until the time of his death, there was no other than the highest regard and respect between us, and I look back with feelings of profound pleasure to my association with him. In all his years in a business which made excessive demands both mental and physical, he was always the urbane gentleman, free from the nauseating ‘ego’ sometimes found in such activities. In all the period of our association no misunderstandings or bickering incident to the bureau affairs ever took place. Mr. Slayton was particularly well-fitted by brain and physique for bureau management – well poised, conservative and an able and broad thinker. His cardinal virtues were his firm integrity, sterling honesty, application and executive force. He had a very thorough knowledge of the geography of the country, location of cities and distances apart, which made him easily the foremost router of attractions.”

“Mr. Slayton had a profound contempt for dishonesty,” says Hon. George R. Wendling. “He was a charitable man – charitable with a charity that suffereth long and is kind. He gave generously not only in money but in sympathy, in forebearance, in encouragement, and he turned his back upon no applicant for favor, not even if the applicant had abused his confidence. He would have died a rich man if he had not been so kind a man.

“He was a good son, a good father, a good husband. I knew much of his life in all these relations, and in filial duty and respect, in loyalty and devotion to his wife, and in parental fondness he was a model man. After thirty years of intimacy and varied business affairs with him I can say that I respected him, that I was fond of him, that I believed in him. Now that he is dead, I honor his memory. In the deep grief of their great bereavement I sympathize with the widow and son.

Not only has the lyceum world lost an upright, capable and efficient manager, but also the community has lost a worthy citizen, the country has lost one who was a soldier and a patriot, and men of every race and creed have lost a friend.”

by The Lyceumite & Talent, Volume 4

June, 1910

In a letter from Greenacre dated July 31, 1894, Vivekananda mentioned, "One Mr. Colville from Boston is here; he speaks every day, it is said, under spirit control."80 In her "Reminscences" Alice Hansbrough added:While he was under contract with that lecture bureau (Slayton-Lyceum Bureau of Chicago] during his first visit to the West, he travelled with a very well-known spiritualist named Colville, who apparently was also under contract to the same bureau. Swamiji used to say, "If you think X is hard to live with, you should have travelled with Colville." The man seems to have had a nurse to look after him all time.81