The Indian “Alsatia”: Sovereignty, Extradition, and the Limits of Franco-British Colonial Policing [The Charu Chandra Roy Affair]

by Mark Condos, Lecturer in Imperial and Global History, School of History, Queen Mary, University of London

2019

Abstract:

By the eve of the First World War, the world’s two most powerful imperial powers, Britain and France, had begun to work together in order to defeat the growing menace posed by transnational anti-colonial networks operating within Europe. When it came to the front lines of the anti-colonial struggle, however, Franco-British collaborative policing efforts continued to be plagued by persistent rivalries and contestations between these erstwhile enemies. This is particularly evident in the case of the French-controlled settlement of Chandernagore in India, which was one of the centres of revolutionary activity in Bengal. This article examines how Chandernagore’s unique legal and political status as a French possession enabled it to become a ‘haven’ or ‘Alsatia’ for Indian revolutionaries operating against the British colonial state. It traces how the persistence of this vestige of French sovereignty placed it at the centre of repeated conflicts between British and French colonial authorities over the detection, arrest, and extradition of these revolutionaries, revealing both the possibilities and limitations of colonial police cooperation. Far from being peripheral in nature, these conflicts cut to the heart of even more fiercely contested debates within the imperial metropole about the relationship between national sovereignty and international law in an increasingly global age.

Funding Details:

This research was supported by the Leverhulme Trust.

Disclosure Statement:

There is no potential conflict of interest.

I – Introduction

On the morning of 23 December 1912, crowds of cheering onlookers lined the cramped streets and roofs of the Chandni Chowk market in Old Delhi to witness what was supposed to be the triumphant arrival of Viceroy Hardinge into the city. Hardinge’s grand entry heralded the official transfer of power from the old, and increasingly embattled British capital of Calcutta, to the shining, new, purpose-built colonial city of New Delhi. At around 11:45 a.m., shortly after the Viceroy’s procession entered the market, a bomb struck Hardinge’s elephant-mounted howdah (carriage) as it passed near a crowded block of buildings about midway between the railway station and the Red Fort.[1] The explosion instantly killed Hardinge’s Indian attendant, as well as a young boy in the crowd. Several others were wounded, including Hardinge, who suffered moderate injuries to the back of his right shoulder and neck, causing him to lose consciousness.[2] This sensational attempt against the life of the highest British official in India sent shockwaves throughout the British Empire and around the world.[3] British officials immediately began one of the largest manhunts in the history of British India for the individuals responsible. David Petrie, an officer within the Indian Department of Criminal Intelligence and future Director General of MI5, was given charge of the investigation, and the considerable resources of all of the provincial CIDs across India were placed at his disposal. Known political suspects were rounded up, questioned, or placed under increased surveillance; additional police were posted across North India to monitor and scrutinise people’s movements around Delhi; and a substantial reward of Rs. 15,000 for information that led to arrest of the individuals responsible for the attack was widely publicised across the country.[4]

British investigators quickly uncovered strong links between the Delhi attack and several other recent bombings committed by Bengali revolutionary groups, including an attack at Midnapur less than a fortnight before on 13 December and another at Calcutta’s Dalhousie Square in March 1911.[5] Tracing the common origin of the bombs used in these attacks, officials eventually narrowed their focus to the French-controlled settlement of Chandernagore, located just outside Calcutta.[6] By June 1913, however, the investigation stalled due to a lack of reliable information, which the British blamed on the uncooperative French police.[7] Writing in late August 1913, the Home Member of the Viceroy’s Council, R.H. Craddock, fumed over the apparent British powerlessness to take action against Indian terrorists who took refuge in Chandernagore:

SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 Held by the French entirely on sufferance, constituting a small enclave within a few miles of the largest city in India, with an incompetent and underpaid Police in the pay of the anarchists, it offers the easiest possible Alsatia to all these political criminals. … In this sanctuary exists unchecked a gang whose object in life is to compass the assassination of high officers of the British Government.[8]

In another note from 5 October 1913, Craddock expressed his frustration in similarly stark terms: ‘SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 Within a few miles of Calcutta is a centre of anarchical conspiracies, where plans may be hatched, bombs manufactured, arms imported, emissaries instructed, and youth depraved, with absolute impunity’.[9]

Despite its general neglect within both South Asian and French historiography, Chandernagore was one of the most important centres of revolutionary activity in Bengal.[10] Between the emergence of the Swadeshi Movement in 1905, and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Chandernagore was the main source of arms for Bengali revolutionaries.[11] Its more liberal press laws also meant that it played a vital role in printing and distributing anti-British propaganda.[12] Even more crucially, the settlement’s close proximity to Calcutta, and the high amount of commercial traffic that passed between its porous borders with British India on a daily basis, made it an obvious choice for Indian revolutionaries seeking to evade the legal jurisdiction of the British police. Because it was not part of British India, and was subject instead to the laws and jurisdiction of the local French colonial authorities, British officials were deeply reliant on the close cooperation and goodwill of their French colleagues when it came to the detection, arrest, and extradition of Indian revolutionaries operating from, or taking refuge within, the settlement. However, as Craddock’s statements suggest, this was far from a smooth and harmonious relationship. Indeed, Craddock’s telling allusion to Chandernagore as an ‘Alsatia’ -– the colloquial term for the area north of the City of London near Whitefriars that provided a legal sanctuary for debtors and other individuals sought by the law until the end of the seventeenth century –- suggests the French had allowed it to become a ‘safe haven’ or legal sanctuary for terrorists.[13]

The existence of such a space so close to the heart of British colonial power in India raises a number of important issues within the history of empire and anti-colonialism. First, it points to the peculiarities and limits of colonial sovereignty within the Indian subcontinent itself. Rather than being an all-powerful colonial regime that stretched smoothly across India, the British state was constrained by the existence of rival and competing sovereignties, like the French. Second, the apparent inability of the French and British to cooperate effectively when it came to putting a stop to Indian revolutionary activity is particularly striking when we consider that this was the same period when these two powers increasingly began to work together in order to police Indian revolutionaries within Europe itself, where the self-professed liberal nature of France and Britain’s imperial metropoles had paradoxically enabled them to develop their anti-colonial politics in similar sorts of ‘safe zones’.[14] This complicates the argument put forward recently by Martin Thomas and Richard Toye that the British and French increasingly acted as ‘co-imperialists’ following the 1904 Entente Cordiale, sharing personnel and much-needed expertise to expand, consolidate, and defend their imperial possessions from various external and internal threats.[15] Instead, it provides a revealing site for the continued conflicts between British and French officials as they attempted to negotiate and balance the competing imperatives of colonial police cooperation and preserving their respective imperial and national interests.[16] Finally, Chandernagore’s unique political and legal status provided new possibilities for the elaboration of Indian anti-colonialism itself. Despite the existence of a wide-array of draconian powers and a higher tolerance for the use of physical violence and other coercive methods for maintaining law and order within the colonial world, Indian revolutionaries in Bengal repeatedly continued to elude British colonial authorities by seeking refuge in this ‘Indian Alsatia’. While it is beyond the scope of this article to present an exhaustive examination of Chandernagore’s contribution to the Indian revolutionary movement, it seeks to understand how the unique political, cultural, legal, and jurisdictional qualities of the settlement afforded Indian revolutionaries operating there an increased freedom of action they did not enjoy in British India. To do so, it explores the highly fraught colonial and imperial politics surrounding the extradition and rendition of Indian revolutionaries between French and British India. These conflicts not only had a profound impact on the unfolding of the Indian nationalist movement and the strategies adopted by revolutionaries, but also fuelled debates within the imperial metropole about national sovereignty and the wider political relations between the French and British governments.

II – A Brief History of Extradition

The practice of surrendering prisoners from one state to another dates back to the ancient world.[17] Extradition treaties were conducted between monarchs who agreed to surrender fugitives who committed treason, attempted regicide, or anything else that might disrupt the established political order.[18] Because the surrender of a person who was granted refuge in another state ran counter to established traditions of asylum and hospitality, extradition from the outset was considered an ‘exceptional’ measure beyond the normal political and legal order.[19] The use of extradition by states to acquire jurisdiction over individuals accused of committing the kinds of ‘political’ crimes outlined above, as opposed to ‘common’ criminal offences (fraud, theft, rape, murder, etc.), remained a central and remarkably durable feature of European extradition agreements until the end of the eighteenth century.[20] During the early nineteenth century, however, the proliferation of railways and steamships made it increasingly easy for criminals of all stripes to quickly travel long distances to evade the authorities of one country, and so states increasingly began to include common criminal offences into extradition agreements.[21] At the same time, political offences were progressively excluded from these treaties. This shift is often attributed to the impact of the French Revolution and the promulgation of the French Constitution of 1793, which promised asylum to individuals exiled from their home countries who were fighting for ‘the cause of freedom’.[22] In 1833, Belgium became the first European nation to codify this principle through what is now known as the ‘political offence exception’.[23] The following year, France and Switzerland both passed similar legislation, and Britain finally followed suit in 1870.[24] Thus, the principle of granting asylum for political crimes rapidly gained acceptance among Western Europe’s more democratic and liberal regimes, enabling them to cast themselves as champions of democracy and freedom.[25]

Once states began to enshrine the political offence exception within their extradition laws, they quickly realised that it was also in their interests to place certain limits on what constituted political crime.[26] Following a failed assassination attempt against Napoleon III in 1855, Belgium was placed in the awkward of position of having to refuse the extradition of the would-be assassins, causing national and international uproar. As a result, Belgium became the first country to introduce an exception to the political offence exception. Known as the Belgian clause or attentat (‘attempt’ or ‘attack’) clause, this provision denied protection to individuals who murdered or attempted to murder heads of state.[27] Over the course of the nineteenth century and twentieth centuries, the attentat clause was gradually expanded to include genocide, war crimes, apartheid, and acts of ‘terrorism’.[28] The attentat clause forced states [to] reconsider how they conceived of legitimate political crimes they still deemed worthy of protection. To do so, they began to differentiate between ‘pure political’ and ‘relative political’ offences. ‘Pure political offences’ referred to actions directed against the political organisation or government of a state which contained no element of common crime, and which did not cause any injury or harm to private persons or property.[29] ‘Relative political’ offences, on the other hand were political acts that also incorporated elements of common crime, such as the assassination of a public official. In the 1890s, for example, European anarchists seeking to overthrow various governments were placed outside the political offender exception.[30] As legal scholars have pointed out, however, relative political offences are highly problematic due to the often hybrid nature between common crime and political crime, and the difficulty in disentangling the two.[31] In the absence of a clear and universally accepted definition of what constitutes legitimate political action, it is difficult for states to maintain their neutrality in international struggles, support individuals and groups genuinely seeking democratic and liberal goals, and to prevent the potentially unjust treatment of prisoners at the hands of authoritarian regimes, especially in this age of heightened terrorism when states are increasingly wary of applying the political offence exception.[32]

In the imperial world, extradition was seldom a straightforward affair, and colonial governments often had to navigate an overlapping and sometimes competing set of extradition procedures and laws within the same imperial political formation. In the case of the British Empire, colonies had to reckon with agreements and procedures developed by their own local governments as well as by the British Parliament back in London. Although imperial statues such as the Extradition Act of 1870 (33 Vict.) and the Fugitive Offenders Act of 1881 (44 & 45 Vict.) were designed to clarify and standardise the procedures governing the extradition of criminals to foreign states and the transfer of fugitives between different parts of the empire,[33] colonial governments nonetheless retained the ability to formulate their own local measures, so long as they were generally in keeping with the parameters of these imperial laws.[34] In India, for example, the Government of India (GOI) passed four different extradition laws and amendments between 1872 and 1903 alone.[35]

The need for so many different extradition laws was a reflection of the complexity of reconciling the GOI’s commitments under the imperial Extradition Act of 1870 with its unusually vast and tangled legal and political geography. Though the most iconic maps of the British Empire depict India as a solid mass of red or pink, suggesting that British dominion stretched evenly and assuredly across the entire subcontinent, this was hardly the case. Aside from the tenuous control exerted by the colonial state over India’s porous frontier regions, the continued existence of its nominally independent ‘princely states’ disrupted the smooth and even unfolding of British legal and political authority.[36] The princely state of Hyderabad, to take one example, was often a reluctant partner when it came to the arrest and extradition of criminals operating across its borders, which led to a series of repeated political disputes and legal contestations with British authorities about the applicability of laws like the Fugitive Offenders Act.[37]

British hegemony was additionally complicated by Portuguese possessions in Goa and Daman along India’s western coast, as well as a handful of small, scattered comptoirs (trading posts) that the French had managed to cling to in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Geographically dispersed, with a total area of little more than 500 square kilometres, and completely dependent on the British for trade and defence, these French enclaves, known collectively as l’Inde Française posed little obvious threat to British rule.[38] Nevertheless, these vestiges of Dupleix’s [Joseph Marquis Dupleix, Governor-General of French India and rival of Robert Clive] once ‘glorious’ Indian empire retained a strong emotional and symbolic significance among France’s pro-colonial lobbyists, despite their relative economic and strategic insignificance within the wider French colonial empire.[39] French officials in India accordingly sought to preserve and advance their nation’s sovereign claims over these territories by repeatedly challenging their British neighbours for greater political concessions through appeals to evolving notions of international law.[40] Thus, far from being a unified political entity, colonial India was punctuated by various enclaves or islands of overlapping, ‘layered’, and competing sovereignty.[41]

As a result, when it came to the arrest and rendition of fugitive criminals, the British colonial government was regularly required to transact with an array of different political formations. Within this context, extradition treaties and agreements can be understood as one of the key ways in which colonial authorities attempted to tame and re-order this tangled legal geography.[42] In the case of Franco-British political relations, extradition treaties were also seen as an important mechanism for reducing tensions and ensuring peaceful relations between these two frequent rivals. As legal scholars have long recognised, one of the key purposes for the development of extradition treaties was to foster mutual respect and goodwill between sovereigns, while also tackling the shared international problem of preventing and punishing criminal acts.[43] As William Magnuson has pointed out, however, this model of rational inter-state exchange could also be profoundly complicated and shaped by domestic politics, which might provide governments or their officials with different incentives to breach these agreements.[44] By the turn of the twentieth century, both Britain and France had an increasingly strong interest in working together to expand, police, and defend their respective empires. British and French officials alike recognised the dangerous threat posed by global revolutionary movements, and should have had strong incentives to work together. Indeed, in the metropole they increasingly did.[45] Yet, in places such as India, this remained a much more complicated affair. Overlapping ideas about extradition, difficulties in distinguishing between ‘pure political’ and ‘relative political’ offences, local political exigencies, as well as wider imperial and metropolitan considerations all combined to hamstring their ability to work together effectively when it came to rendering fugitives in India.

III – L’Affaire Charu Chandra Roy

Just after 8 a.m., on 22 June 1908, British and French police forces raided the home of Charu Chandra Roy in Chandernagore. When the police entered the residence, Godfrey Charles Denham, a British officer within the Special Branch of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the Bengal Police, produced and read out a warrant for Roy’s arrest. Roy was then placed under the custody of the French Commissioner of Police, E. Prieur, while Denham and the French police searched the house for an hour. Following the search, Roy was conducted into a car and taken by the French authorities to the Prosecutor’s Office, where he was officially given over to the custody of Denham. An adjutant then escorted Denham and Roy to a jetty where a steamship from Calcutta was waiting to convey them down the Hooghly river and into British territory.[46] At first glance, Roy’s arrest and extradition appear to offer a glimpse into the successful workings of Franco-British colonial policing of Indian revolutionaries. Roy’s extradition, however, quickly became a source of international controversy which demonstrated the complexity and the limits of collaborative colonial policing in India.

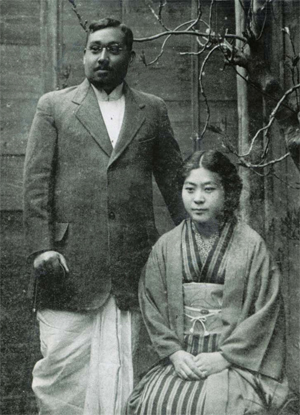

On the surface, Roy was a respectable and prominent citizen of the French settlement. In addition to being the deputy director of the local Dupleix College, he was also a registered elector who helped select India’s representative to the French Chamber of Deputies in Paris.[47] Roy, however, was also a leading Swadeshi activist and one of the main revolutionary leaders in Chandernagore. In addition to promoting the movement to his students at Dupleix College, Roy also organised boycotts and public meetings within the settlement. On 4 April, one of these protests had turned violent after armed soldiers and police were despatched by Mayor Paul Emile Léon Tardivel to shut it down.[48] In revenge, Roy gave his approval to Barin Ghosh, one the leaders of the Calcutta-based Manicktolla [Maniktala] secret society, to assassinate Tardivel.[49] Ghosh and his associates subsequently attempted to kill Tardivel by throwing a bomb into his dining room on the night of 12 April 1908, but the detonator failed and Tardivel escaped unharmed.[50] Based on his public activities and his known connections with the Manicktolla group, the Bengal Government suspected that Roy was closely involved in the preparation of explosive materials and the planning of various other terrorist attacks, including an assassination attempt against former Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, Sir Andrew Fraser, and the notorious botched attack against Magistrate Douglas Kingsford at Muzzafarpur.[51] Following the Kingsford attempt, the members of the Manicktolla group were arrested and prosecuted in a high-profile trial that became known as the Alipore Conspiracy Case.[52] During their investigation, British officials discovered that two of the accused in the Alipore Conspiracy Case, Upendra Nath Banerji and Kanailal Dutta, had actually studied under Roy at Dupleix College, and that Roy also had close connections with Narendra Nath Goswami, who later turned state’s evidence and was assassinated in the Alipore prison by Dutta and Satyendra Nath Bose.[53] It was Goswami’s testimony that finally provided British authorities with sufficient evidence to obtain a warrant for Roy’s arrest and extradition, after which Roy was transferred to the same prison ward in the Alipore jail as the Manicktolla conspirators, including Aurobindo Ghosh.[54]

Shortly after Roy’s extradition and imprisonment, the case against him began to unravel. Because British authorities believed Roy had been directly involved in helping to prepare explosives and organise attacks, his arrest warrant cited charges under sections 107, 150, and 157 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) of 1860, and sections 19 and 20 of the 1878 Indian Arms Act.[55] British officials had hoped that incriminating evidence, including bomb-making materials, would be found at his home, and were obviously disappointed when the police came back empty-handed. Lacking sufficient evidence to indict him for the aforementioned charges, the British authorities decided to change their strategy and arraign Roy under the much more serious and wide-ranging charges of conspiring to ‘wage war’ against the sovereign (sections 121, 121A, and 123 of the IPC).[56] This fateful decision to unilaterally revise the charges levied against Roy would ultimately force a confrontation between the French and British governments over the extremely sensitive issue of national sovereignty and the respective rights of their citizens and subjects.

From the outset, French officials had been uneasy about extraditing such a prominent public official, and the Bengal Government became noticeably incensed when it had to wait for over two weeks while the cautious Administrator of Chandernagore, Maurice Guizonnier, considered their request.[57] Although Guizonnier reluctantly agreed to help his British counterparts, he wrote to his superior, Governor Adrien Bonhoure, highlighting the ‘delicate’ judicial and political questions surrounding the case. In particular, he gestured to the complexities of Britain and France’s overlapping extradition treaties and agreements.[58] Roy’s extradition had been requested according to the Franco-British Convention of 1815, which governed the sale and production of salt and opium in India. Article 9 of this treaty provided for the mutual extradition of both Indians and Europeans who violated the laws of British and French India.[59] In 1876, however, the French and British governments concluded a new Extradition Treaty, which included an article specifying that ‘nationals’ were exempt from extradition.[60] Guizonnier, therefore, concluded that it would have been within French rights to refuse Roy’s extradition.[61] When the General Prosecutor and Chief of the Judicial Service, A. Raynaud, weighed in a few weeks later, however, he pointed out that the 1876 Treaty specifically did not alter or revoke the wide-ranging powers granted by article 9 of the 1815 Convention. ‘Nationals’, Raynaud concluded, ‘are therefore liable to extradition in India’.[62] In light of the confusion about the validity of the procedure followed in Roy’s arrest and extradition, Bonhoure decided to refer the entire case to his superior in Paris, the Minister for the Colonies, Raphaël Milliès-Lacroix.[63]

While Roy languished in a British jail cell and the French authorities debated the legality of the extradition, his brother, Kanailal Roy Gupta, began an aggressive publicity and letter-writing campaign in the hopes of obtaining his release. Three day’s after Roy’s arrest, Gupta, published an open letter of vigorous protest addressed to the French Public Prosecutor in Chandernagore in the local newspaper, Matribhumi (motherland). With its motto, ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’, Matribhumi was known for its advocacy of French republican and liberal values, while also being a prominent mouthpiece for Indian radicals and revolutionaries.[64] In his letter, Gupta proclaimed his brother’s innocence and argued that both the search of Roy’s house, as well as his arrest and extradition were technically illegal. To make his case, Gupta stressed that Roy was a loyal and respectable ‘French citizen’, and cited the 1876 Extradition Treaty, which guaranteed that ‘citizens’ were protected against extradition.[65] In a subsequent letter published in Matribhumi on 25 July, Gupta renewed his attacks against the legality of the extradition, this time pointing out that the 1876 Treaty specifically prohibited the extradition of individuals accused of ‘political crimes’.[66] As we have seen, the convention of not extraditing political prisoners was a vital principle of international law governing the rendition of prisoners from one state to another. It was considered so important, in fact, that the French and British had concluded a separate agreement in 1861 which clarified that while the GOI retained ‘the widest possible powers of extradition’ under the 1815 Convention, that this did not apply to ‘political offences’.[67]

Gupta clearly understood that upholding the political offence exception would be an important priority for a self-professed liberal regime like France that sought to position itself as a champion of liberty and democracy, and so on 15 July, he personally wrote to Bonhoure, informing him that the British had abandoned the initial charges against Roy, and had replaced them with charges for political crimes. Gupta stirred the pot further by claiming that the ‘charges of murder and attempted murder against Charu Chandra Ray were nothing more than a ploy to catch your good faith unawares and to easily obtain his extradition’.[68] Two weeks later, on 23 July 1908, Gupta wrote a similar letter to the Minister for the Colonies, Milliès-Lacroix, peppering it with patriotic language and beseeching the Minister to protect the rights of a fellow citizen.[69] In yet another letter to Bonhoure from 31 July 1908, Gupta forwarded various documents and correspondence obtained from the British authorities that provided irrefutable evidence that Roy was to be prosecuted for crimes against the state, and reminded him that France did not extradite individuals accused of political offences. He also argued that the involvement of a British officer in the search and arrest invalidated the entire extradition procedure. According to Gupta, only French agents had the legal authority to arrest Roy and search his home, and Roy should have been conducted to the Chandernagore frontier before being handed over to the British authorities.[70]

Back in Paris, the pro-colonial press attempted to turned Roy’s plight into a national cause célèbre. One sympathetic daily entitled La Politique Coloniale came to Roy’s defence by reprinting Gupta’s letters and whipping up patriotic sentiment and outrage by claiming that the arrest of a French civil servant by a British police officer represented a violation of France’s sovereignty.[71] Another newspaper entitled La Presse Coloniale decried Roy’s treatment as ‘monstrous’, declaring that ‘[t]here could be no more overt violation of our fellow citizens’ rights and no greater compromise to their interests and the interests of the metropole’.[72] As the press stoked the flames of public outrage, the League for the Defence of the Rights of Man and Citizens also became involved in the affair. Founded in 1898 to defend Captain Alfred Dreyfus against his unjust and illegal conviction for treason during the infamous Dreyfus Affair which dominated French politics between 1894 and 1906, the League was a powerful and politically influential left-wing organisation.[73] On 21 August, the President of the League, Francis de Pressensé, wrote to Milliès-Lacroix, drawing his attention to Roy’s case:

If the facts relayed … are accurate, our countryman was the victim of a monstrous violation of our laws, and indeed of the law of man. I am aware of the serious events which led a renowned liberal, Lord Morley, Secretary of State for India, to order measures of prevention and suppression to be enforced across the entire peninsula. Yet the law, the law of man, and international guarantees cannot, in any circumstance, exist in isolation. France’s honour, and the safety of her representatives, are at stake.[74]

As such, De Pressensé implored Milliès-Lacroix and the French government to undertake ‘the most energetic intervention’ on Roy’s behalf to obtain his release from the British authorities.

As the pressure mounted, the French government found itself on the defensive, searching for new ways to justify and uphold the legality of the extradition. In the metropole, much of the outrage over the Roy case appears to have been driven by the misapprehension that he was a French ‘citizen’, rather than a French ‘subject’. The French government therefore tried to deflect criticism by clarifying that Roy was not, in fact, a natural-born Frenchman, and was simply a ‘native subject’. This meant that, from a judicial point of view, Roy’s extradition was completely legal and consistent with French treaty obligations toward the British.[75] Officials also continued to insist that the proper extradition procedure had been followed, and that there had been no violation of French sovereignty.[76] All of this changed, however, when the Bengal Government, after numerous delays, finally confirmed on 15 September that they had, indeed, changed the charges against Roy.[77] The following day, Guizonnier registered his strong disapproval to Bonhoure, and expressed irritation that the Bengal authorities had previously been so unresponsive to his requests for clarification about the progress of Roy’s case.[78] Now that the British authorities had demonstrated their bad faith in unilaterally deciding to switch the charges without asking the French for authorisation, Guizonnier believed that it was within their rights to challenge the extradition.[79]

From a strictly legal point of view, there was little the French government could officially do unless a verdict of guilty was rendered against Roy.[80] By October 1908, however, public scrutiny of Roy’s case had become so great that the French government feared the potential national embarrassment and domestic political backlash that would occur if the apparent irregularities of the affair were officially raised in the Chamber of Deputies. Eager to portray themselves as defenders of liberty, while also avoiding any appearance that they had violated the generally recognised principles of granting asylum to political prisoners, the French authorities intervened on Roy’s behalf and pressured the British to retract the charges of conspiracy and waging war against the sovereign. Writing to the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and future Viceroy of British India, Charles Hardinge, French Ambassador Paul Cambon pointed out SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 that ‘Great Britain had always declared herself as opposing the principle of extraditions for political offences’ and asked that they limit themselves to the original charges listed on Roy’s arrest warrant.[81] Two days later, on 12 October 1908, Cambon sent another letter to the Foreign Office, urging them to ‘avoid introducing any political aspect into this judicial affair’.[82] Just over two weeks later, on 27 October, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally reported to the Ministry for the Colonies that the British had relented and withdrawn all the political charges against Roy.[83] With insufficient evidence to proceed against Roy for the initial charges, and the option of pursuing him for political crimes now closed to them, British authorities were compelled to drop all charges against Roy, and he was finally released from the Alipore jail on 7 January 1909.

The controversy provoked by the handling of Roy’s case fed into a growing sense distrust and simmering tension between British and French authorities. Embittered by the apparent reluctance on the part of the French to aid them in their efforts, the Bengal Government concluded that drastic measures would need to be taken in [the] future if French authorities were not more cooperative when it came to extraditing individuals accused of political offences:

If the French Government persisit [sic] in a wide construction of the word ‘political’ and in the perpetuation of the state of things described, it is obvious that the old friendly and altogether easy-going relations between the local administrations must cease. The only possible course for this Government would be at great expense to surround Chandernagore with a cordon of police, and to instute [sic] the severest scrutiny for contraband of every kind. Such action would impose intense inconvenience on the residents of the settlement and there is no doubt that the French local authorities at least would recommend any possible concession in order to avoid it.[84]

The French, for their part, were clearly annoyed about the apparent British duplicity in changing the charges against Roy, but also realised they needed to maintain the goodwill of their powerful neighbours. In an effort to placate their irritated British counterparts, Bonhoure unsuccessfully attempted to block Roy’s reinstatement as deputy director of Dupleix College shortly after his release from prison.[85] If Roy’s reinstatement was not insulting enough to the Bengal Government, the appearance of a copy of the radical Jugantar newspaper on the public notice board at Dupleix College a few days later was seen as positively provocative. Commenting on the incident, the Calcutta-based newspaper The Englishman made veiled, yet sufficiently obvious, insinuations that Roy was responsible, and chastised French authorities for not doing enough to ‘prevent Chandernagore becoming a spawning-bed for sedition-mongers’.[86] After reading The Englishman article, the French Consul General in Calcutta, Ernest Ronssin expressed his understandable concern that the French would permit someone who openly ‘preaches’ murder against British authorities to continue to serve as a public official, and warned that Roy’s known connections with the Chandernagore ‘anarchists’ would erode the good relations between the British and French in India.[87]

The Charu Chandra Roy affair left a bad taste in the mouths of both British and French officials alike. Yet just over a year after its conclusion, the French and British governments found themselves drawn into an even more acrimonious conflict surrounding the extradition of another Indian revolutionary. On 8 July 1910, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar escaped from his British captors as his ship passed through the French port city of Marseilles from London enroute to India, where he was meant to face trial. Savarkar jumped ship and managed to swim ashore, but was promptly arrested by a French police officer and surrendered back to the British. When the French public caught wind of these events, however, there was an outcry against the impromptu extradition. This became the spark for a major diplomatic incident between the two powers, at the heart of which lay an intense legal debate about national sovereignty in an increasingly international age. Although the case was finally decided at the Hague in favour of the British, it continued to cast a long shadow over the still fragile Franco-British Entente Cordiale.[88] As Edouard Néron, a member of the French Chamber of Deputies put it in an article written for Les Annales Coloniales shortly after the verdict was rendered: ‘This judgment will, undoubtedly, be of great significance. It is concerned, in fact, with one of the most delicate questions concerning territorial sovereignty and the right of asylum, and it is probable that it will form the subject of jurisprudence for similar disputes in the future’.[89]

Although neither the political scandal nor the ensuing diplomatic crisis were on the same scale as that of the Savarkar case, the Roy affair nonetheless set an important precedent within India itself when it came to determining the possibilities and limits of Franco-British collaborative colonial policing. After British officials learned that Aurobindo Ghosh [Sri Aurobindo] had fled to Pondicherry via Chandernagore in 1910, Secretary of State for India John Morley gestured explicitly to the Roy case when he ordered Viceroy Hardinge not to pursue the French for his extradition in the hopes of avoiding a similar political incident.[90] The apparent success of Gupta’s letter-writing offensive and the ensuing publicity campaign by liberal newspapers and organisations also provided a sobering lesson to the French authorities about the problems that could arise if they were seen to be colluding too openly with their British counterparts. This was reinforced during King George V’s royal visit to India in 1911, when the League for the Defence of the Rights of Man pressed the French government over the presence of special undercover British police officers in Chandernagore, claiming that it was an ‘invasive’ violation of French sovereignty.[91] Finally, the apparent confusion surrounding Britain and France’s overlapping extradition agreements and procedures highlighted the importance of clarifying these issues, and prompted French colonial officials to try and obtain greater power to resist extradition requests when they were deemed to run counter to their interests.[92] As we shall see in the following section, all of these factors played a role in the inability of the French and British authorities to apprehend Rash Behari Bose, the mastermind behind the assassination attempt against Viceroy Hardinge in 1912.

IV– The Flight of Rash Behari Bose

In February 1914, a series of police raids in Delhi and Lahore uncovered evidence that the mastermind behind the 1912 assassination attempt against Viceroy Hardinge was Rash Behari Bose, the head clerk in the Forest Department at Dehradun in Uttarakhand.[93] The police subsequently attempted to arrest Bose in Lahore, but he managed to escape and eventually made his way back to his home town of Chandernagore, where he had even studied under Charu Chandra Roy at Dupleix College. Though it did not take long for British authorities to pick up Bose’s trail, it did take them several days to obtain permission from the French authorities to conduct a search of his house.[94] By the time French and British police raided Bose’s home on the morning of 8 March, Bose had already escaped to Benares after reading reports in the Calcutta-based newspapers advertising the large reward for his arrest.[95] Two subsequent searches of his domicile turned up nothing more than a few proscribed publications.[96] Although Bose departed Chandernagore for Benares before the British began their extradition proceedings, Petrie later lamented how ‘the delay inseparable from the arranging of extradition formalities has greatly prejudiced our chances of capturing him’.[97] The Governor of the French Settlements, Alfred Albert Martineau, however, saw it slightly differently, and described the failure to apprehend Bose and the repeated impositions placed on his administration by the British authorities as ‘a humiliating and grotesque situation’.[98]

On 5 March 1914, after learning that the British authorities were in hot pursuit and seeking his extradition from Chandernagore for violations of the Explosives Act (1884) and section 302 (murder) of the IPC, Bose petitioned the French Minister for the Colonies in Paris, Albert François Lebrun, to deny their request. Citing both the Treaty of 1815 and the Convention of 1876, Bose insisted that the ‘political character’ of his supposed crimes protected him against extradition and implored Lebrun to grant him asylum.[99] Less than two weeks later, on 16 March, Bose’s uncle, Nandakisor Sinha, sent a similar petition to Martineau. Sinha also argued that the Convention of 1876 protected Bose from extradition due to the political nature of his alleged crimes, and he beseeched Martineau for the ‘protection of the French Government’.[100] As with the various petitions sent on behalf of Roy six years earlier, Bose and Sinha both presented an ardently juridical defence against Bose’s extradition by insisting it was the legal duty of the French authorities to grant him political asylum. At the same time, they also implicitly advanced an important moral argument as well. By casting Bose in the role of a legitimate freedom fighter, these petitions attempted to exploit French national pride about being a self-professed liberal, democratic state that was committed to the causes of freedom and justice.

When the pro-colonial press caught wind of the Bose affair, they also rallied to his defence. On 15 April 1914, La Presse Coloniale published an article entitled ‘An Illegal Extradition in Chandernagor’, accusing the British Viceroy of ‘having nothing better to do’ than ‘invade’ French territory in order to ‘ransack’ the houses of French citizens and subjects without sufficient warning or even official authorisation.[101] According to the article, this represented an unacceptable threat to the security and rights of French citizens and subjects: ‘SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 our compatriots from overseas are not only frustrated by the searches of a foreign nation, but those who carry even some small suspicion are still extradited with an unlawful and abusive ease’.[102] As Henry Croisilles, the paper’s correspondent put it, ‘We may soon see foreign police entering the home of any citizen without prior permission’.[103] Alarmist as it may have seemed, this kind of rhetoric touched a nerve with the French public, tapping into their sense of patriotism and also insecurity and emotional attachment to these vestiges of their ‘lost’ empire.[104]

On 21 April 1914, Gaston Doumergue, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, wrote to Lebrun and compared Bose’s plea for protection to the one mounted in 1908 by Roy and his supporters. Doumergue reminded Lebrun that his predecessors had ultimately sanctioned Roy’s extradition because the initial charges levied by the British authorities constituted common criminal offences, and were not protected by the political offence exception.[105] Thus, regardless of the overtly political implications of Bose’s alleged offences, their violent nature also necessarily invalidated them from being non-extraditable offences. As Doumergue put it, ‘It is the first duty of insurgents or rebels who claim to be in a state of war to abstain from barbarous or disloyal acts which the customs of war reject’.[106] Doumergue was well aware of the political difficulties that would arise if the French were seen to being offering shelter to violent revolutionaries, and he took a hard line by insisting that the French colonial authorities should do everything in their power to cooperate and help the British in their efforts.[107]

In a subsequent letter, Doumergue reiterated that the French were not to extend Bose any protection because of both the special nature of the case, as well as the difficulty of extending political legitimacy to ‘anarchist attacks committed in Hindustan’.[108]

Yet despite his avowed commitment to rooting out Indian revolutionaries, Doumergue also recognised that French sovereignty and national pride might be damaged if they were seen to be too acquiescent toward British demands. As such, he stressed that French colonial authorities should not allow their cooperation with the British to compromise the ‘independence of our authority in our Indian possessions, however compelling the obligations of applying Article 9 of the Convention of 7 March 1815’.[109] In order to minimise this, Doumergue suggested that in future the French authorities could simply expel revolutionaries from their territory.[110] In response, Martineau agreed that expulsion would help ‘avoid the ever-unpleasant procedure of extradition’, but cautioned that it ‘would in reality be tantamount to purely and simply handing over of criminals to the English authorities’.[111] Martineau was particularly sensitive to how these kinds of political entanglements threatened French sovereignty in India and political stability back home, and was prepared to take fairly remarkable steps to avoid future disputes of this nature. In May 1914, after Bose managed to elude the French and British police, Hardinge asked Martineau to do everything in his power to arrest Bose should he ever return to Chandernagore. Although Martineau offered his assurances to Hardinge, he secretly instructed the Administrator of Chandernagore to inform Bose’s family that he would be arrested if he returned. Writing to Maurice Raynaud, the Minister of the Colonies in Paris, Martineau justified this bold decision by arguing that it would help prevent even greater ‘diplomatic difficulties’.[112]

For Martineau, the kinds of political disputes surrounding extradition and inter-imperial policing were merely symptomatic of the much more fundamental and apparently insurmountable problem of having two clashing imperial sovereignties in India. As a result, Martineau believed that the only viable solution was for France to cede control of Chandernagore directly to the British in return for expanded territorial concessions around Pondicherry.[113] As he put it in a letter from 1917:

In Chandernagor we assume a most thankless and futile role. We are obliged to defend, in the name of our principles, a right of hospitality which may turn against our interests, and yet, after the victories of the Marne and Verdun, which have caused the greatest stir in India, we cannot sacrifice those principles which bind us. That is why the cession of Chandernagor has always seemed to me the most political and honourable way of escaping from an extremely difficult and, as it were, hopeless moral situation.[114]

Yet despite Martineau’s best efforts, and a sporadic series of informal and formal negotiations between the British and French governments over the next several years, this proposal ultimately came to nothing.[115]

Following his flight from Chandernagore to Benares, Bose continued his revolutionary activities, and was one of the key organisers in the unsuccessful Ghadar uprising in Punjab that terrified the British colonial establishment during the First World War.[116]

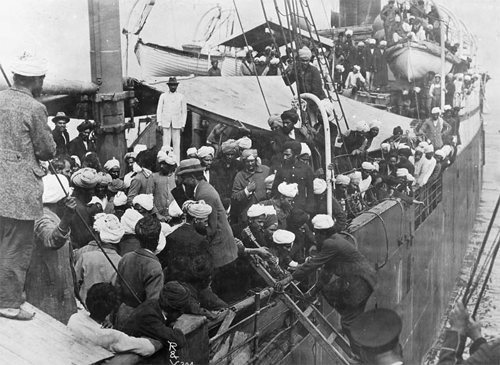

The Ghadar Mutiny, also known as the Ghadar Conspiracy, was a plan to initiate a pan-Indian mutiny in the British Indian Army in February 1915 to end the British Raj in India. The plot originated at the onset of World War I, between the Ghadar Party in the United States, the Berlin Committee in Germany, the Indian revolutionary underground in British India and the German Foreign Office through the consulate in San Francisco. The incident derives its name from the North American Ghadar Party, whose members of the Punjabi Sikh community in Canada and the United States were among the most prominent participants in the plan. It was the most prominent amongst a number of plans of the much larger Hindu–German Mutiny, formulated between 1914 and 1917 to initiate a Pan-Indian rebellion against the British Raj during World War I. The mutiny was planned to start in the key state of Punjab, followed by mutinies in Bengal and rest of India. Indian units as far as Singapore were planned to participate in the rebellion. The plans were thwarted through a coordinated intelligence and police response. British intelligence infiltrated the Ghadarite movement in Canada and in India, and last-minute intelligence from a spy helping to crush the planned uprising in Punjab before it started. Key figures were arrested, mutinies in smaller units and garrisons within India were also crushed.

Intelligence about the threat of the mutiny led to a number of important war-time measures introduced in India, including the passages of Ingress into India Ordinance, 1914, the Foreigners act 1914, and the Defence of India Act 1915. The conspiracy was followed by the First Lahore Conspiracy Trial and Benares Conspiracy Trial which saw death sentences awarded to a number of Indian revolutionaries, and exile to a number of others. After the end of the war, fear of a second Ghadarite uprising led to the recommendations of the Rowlatt Acts and thence the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

-- Ghadar Mutiny, by Wikipedia

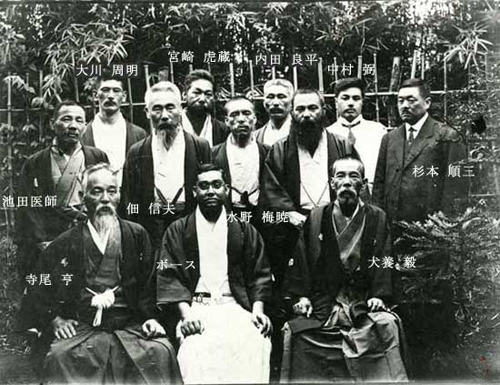

After the failed Ghadar uprising, Bose once again managed to evade the British authorities and return to Chandernagore, before finally escaping to Japan in May 1915. Although Bose’s escape to Japan signalled an end to the controversy with the French government, British officials continued to pursue Bose’s extradition with the Japanese authorities. In the absence of an official extradition treaty with Japan and faced with the ever-problematic issue of extraditing persons accused of political offences, Hardinge resorted to diplomatic subterfuge. Concealing the political nature of Bose’s offences, Hardinge applied considerable pressure through the British embassy in Tokyo and depicted Bose as part of a wider German conspiracy to undermine the Allied war effort.[117] When the Japanese government finally agreed to issue a deportation order, Bose went into hiding with the help of his friends connected to the ultranationalist Kokury [Black Dragon Society/Kokuryu-Kai] SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 ūkai and Gen’y SEQ CHAPTER \h \r 1 ôsha secret societies. The deportation order was eventually rescinded in March 1916, and Bose freely continued to write and lecture against British colonial rule in India throughout the 1920s and 30s.[118]

The ultimate failure of British authorities to apprehend one of the would-be assassins of the Viceroy of India was a great blow to their prestige, and provides yet another striking demonstration of the enduring fault lines that continued to plague Franco-British colonial police cooperation during this period. In August 1913, while harried British officials desperately sought those responsible for the Delhi bombing, R.H. Craddock vented his frustration about their inability to intervene in the affairs of Chandernagore. The French police, Craddock claimed, were underfunded, understaffed, and either too corrupt, timid, or incompetent to suppress the revolutionaries who operated there.[119] As a result, Chandernagore had become a dangerous haven of sedition, propaganda, and terrorist violence. ‘We cannot’, Craddock wrote, ‘go on quietly in the knowledge that Chandernagore contains men skilled in making bombs and living there in impunity, who can at any time plot an outrage of their own, or supply bombs to trusted emissaries of seditionaries in other parts of India who make their plots and supply their own throwers’.[120] As Tegart put it a few years later, ‘the Chandernagore Settlement provides, in its present state, an Alsatia for revolutionary fugitives and is an active centre of plots directed towards the subversion of British rule in India’.[121] Although it would be unfair to blame Bose’s initial escape from Chandernagore on the French authorities, the inability of the British police to operate freely within the French settlement certainly did not help matters. Martineau’s somewhat astonishing decision to warn Bose’s family that he would be arrested if he ever returned also reveals how the patience of his beleaguered colonial administration had run out, and that this kind of close police cooperation was ultimately incompatible with upholding France’s dignity and honour.