by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/15/20

Office of Strategic Services

OSS insignia[1]

Agency overview

Formed: June 13, 1942

Preceding agency: Coordinator of Information

Dissolved: September 20, 1945

Superseding agency: Central Intelligence Agency

Employees: 13,000 estimated[2]

Agency executives: MG William Joseph Donovan, Coordinator of Information; BG John Magruder, Director for Intelligence

[x]

CIA film describing OSS recruitment, training, and missions during WWII

OSS officers came from all walks of life, and brought interesting life experiences

and unusual skills to their work.

It was in many ways a dream team that would

never be seen again. A few used their status to their advantage,

like Hollywood director John Ford who used his

easy access to cameras to gather information for the Allied forces.

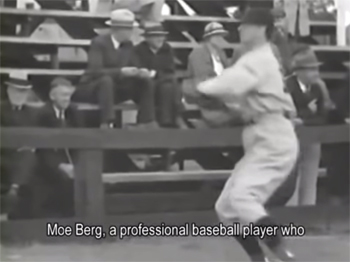

Moe Berg, a professional baseball player who played for a number of teams, including the Red Sox, helped the OSS with his fluency in many European languages.

And movie star Sterling Hayden took his acting to the next level to go behind enemy lines in Yugoslavia. Other OSS operatives had backgrounds ranging from academics to entertainers, to circus performers,

and even swimmers and safecrackers. Men and women were recruited from all over the country. OSS is remembered for having a good record

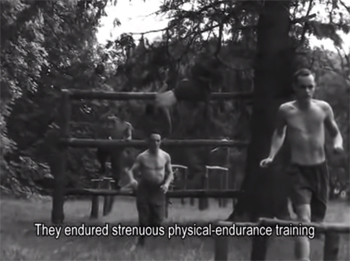

for recruiting and employing women. OSS officers underwent vigorous training in guerrilla warfare and new cloak-and-dagger

combat methods such as espionage and lethal covert action. They were also required to take

a variety of subjects in the classroom.

Trainees were hidden away in camps where they lived under realistic conditions in order to prepare them for the conditions

that they would have to endure on missions overseas.

They endured strenuous physical-endurance training on outdoor obstacle courses designed to target

and exercise the muscles most used in combat.

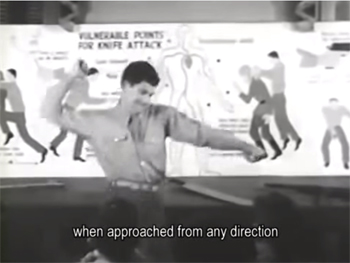

They learned the correct way to hold and shoot a pistol and practiced this form in front of mirrors until it was perfected. OSS trainers taught them maneuvers like the chin jab,

that would cripple an opponent in hand-to-hand combat. Trainees practiced escape techniques to use

when approached from any direction, and how to disarm an enemy. They were also taught how to aid a comrade in trouble.

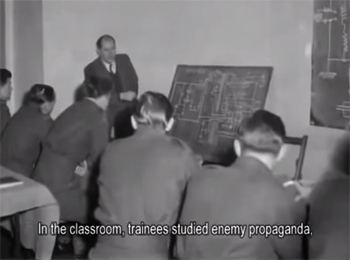

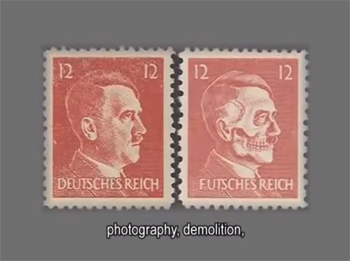

In the classroom, trainees studied enemy propaganda,

photography,

demolition,

and cross-country reconnaissance. The secluded property in Maryland that later

became Camp David was used to train OSS officers for service in Europe. The Jedburgs were paramilitary units who operated in France, Belgium, and Holland,

and worked alongside the local resistance. In addition to their physical training and familiarization with the conditions

they would encounter on the ground in Europe,

Jedburgs learned French and other languages, as well as how to read maps and compasses, and how to use ciphers.

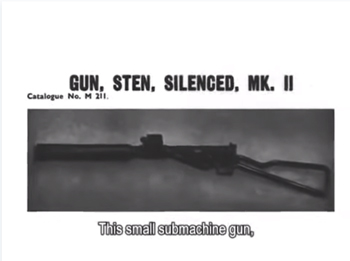

They became expert nighttime navigators, parachutists, and radio communicators. These units were also trained to use special weapons -- a favorite being the sten gun.

This small submachine gun, nicknamed a "pipe and bedspring," had three important advantages: it was inexpensive to produce, simple to dismantle, and easy to conceal.

The training process to become an OSS officer was not easy or conventional.

With the outbreak of WWII, President Roosevelt looked to new techniques to take the fight to the enemy.

OSS training did the trick.

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was a wartime intelligence agency of the United States during World War II, and a predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)[3] to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branches of the United States Armed Forces. Other OSS functions included the use of propaganda, subversion, and post-war planning. On December 14, 2016, the organization was collectively honored with a Congressional Gold Medal.[4]

Origin

Prior to the formation of the OSS, the various departments of the executive branch, including the State, Treasury, Navy, and War Departments conducted American intelligence activities on an ad hoc basis, with no overall direction, coordination, or control. The US Army and US Navy had separate code-breaking departments: Signal Intelligence Service and OP-20-G. (A previous code-breaking operation of the State Department, the MI-8, run by Herbert Yardley, had been shut down in 1929 by Secretary of State Henry Stimson, deeming it an inappropriate function for the diplomatic arm, because "gentlemen don't read each other's mail."[5]) The FBI was responsible for domestic security and anti-espionage operations.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was concerned about American intelligence deficiencies. On the suggestion of William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, Roosevelt requested that William J. Donovan draft a plan for an intelligence service based on the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and Special Operations Executive (SOE). After submitting his work, "Memorandum of Establishment of Service of Strategic Information", Colonel Donovan was appointed "coordinator of information" on July 11, 1941, heading the new organization known as the office of the Coordinator of Information (COI).

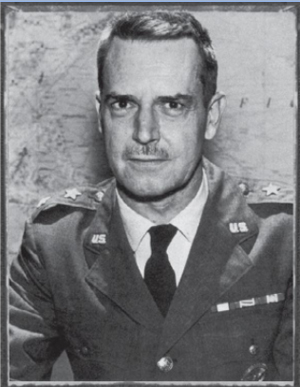

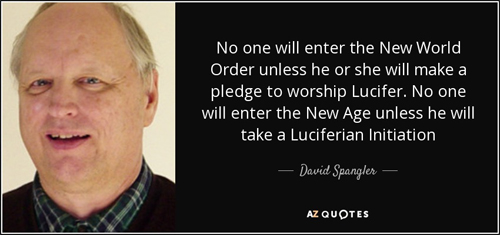

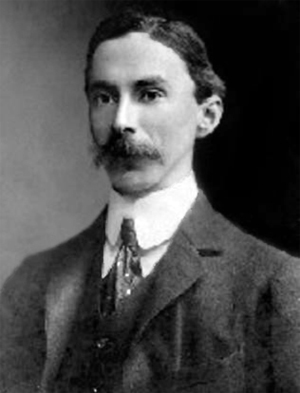

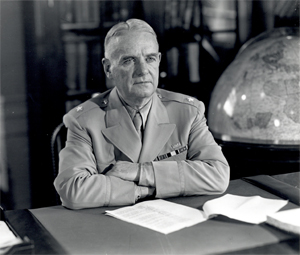

William J. Donovan

Thereafter the organization was developed with British assistance; Donovan had responsibilities but no actual powers and the existing US agencies were skeptical if not hostile. Until some months after Pearl Harbor, the bulk of OSS intelligence came from the UK. British Security Co-ordination (BSC) trained the first OSS agents in Canada, until training stations were set up in the US with guidance from BSC instructors, who also provided information on how the SOE was arranged and managed. The British immediately made available their short-wave broadcasting capabilities to Europe, Africa, and the Far East and provided equipment for agents until American production was established.[6]

The Office of Strategic Services was established by a Presidential military order issued by President Roosevelt on June 13, 1942, to collect and analyze strategic information required by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and to conduct special operations not assigned to other agencies. During the war, the OSS supplied policymakers with facts and estimates, but the OSS never had jurisdiction over all foreign intelligence activities. The FBI was left responsible for intelligence work in Latin America, and the Army and Navy continued to develop and rely on their own sources of intelligence.

Activities

General William J. Donovan reviews Operational Group members in Bethesda, Maryland prior to their departure for China in 1945.

OSS missions and bases in East Asia

OSS proved especially useful in providing a worldwide overview of the German war effort, its strengths and weaknesses. In direct operations it was successful in supporting Operation Torch in French North Africa in 1942, where it identified pro-Allied potential supporters and located landing sites. OSS operations in neutral countries, especially Stockholm, Sweden, provided in-depth information on German advanced technology. The Madrid station set up agent networks in France that supported the Allied invasion of southern France in 1944. Most famous were the operations in Switzerland run by Allen Dulles that provided extensive information on German strength, air defenses, submarine production, and the V-1 and V-2 weapons. It revealed some of the secret German efforts in chemical and biological warfare. Switzerland's station also supported resistance fighters in France and Italy, and helped with the surrender of German forces in Italy in 1945.[7]

For the duration of World War II, the Office of Strategic Services was conducting multiple activities and missions, including collecting intelligence by spying, performing acts of sabotage, waging propaganda war, organizing and coordinating anti-Nazi resistance groups in Europe, and providing military training for anti-Japanese guerrilla movements in Asia, among other things.[8] At the height of its influence during World War II, the OSS employed almost 24,000 people.[9]

From 1943–1945, the OSS played a major role in training Kuomintang troops in China and Burma, and recruited Kachin and other indigenous irregular forces for sabotage as well as guides for Allied forces in Burma fighting the Japanese Army. Among other activities, the OSS helped arm, train, and supply resistance movements in areas occupied by the Axis powers during World War II, including Mao Zedong's Red Army in China (known as the Dixie Mission) and the Viet Minh in French Indochina. OSS officer Archimedes Patti played a central role in OSS operations in French Indochina and met frequently with Ho Chi Minh in 1945.[10]

One of the greatest accomplishments of the OSS during World War II was its penetration of Nazi Germany by OSS operatives. The OSS was responsible for training German and Austrian individuals for missions inside Germany. Some of these agents included exiled communists and Socialist party members, labor activists, anti-Nazi prisoners-of-war, and German and Jewish refugees. The OSS also recruited and ran one of the war's most important spies, the German diplomat Fritz Kolbe.

From 1943 the OSS was in contact with the Austrian resistance group around Kaplan Heinrich Maier. As a result, plans and production facilities for V-2 rockets, Tiger tanks and aircraft (Messerschmitt Bf 109, Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, etc.) were passed on to Allied general staffs in order to enable Allied bombers to get accurate air strikes. The Maier group informed very early about the mass murder of Jews through its contacts with the Semperit factory near Auschwitz. The group was gradually dismantled by the German authorities because of a double agent who worked for both the OSS and the Gestapo. This uncovered a transfer of money from the Americans to Vienna via Istanbul and Budapest, and most of the members were executed after a People's Court hearing.[11][12]

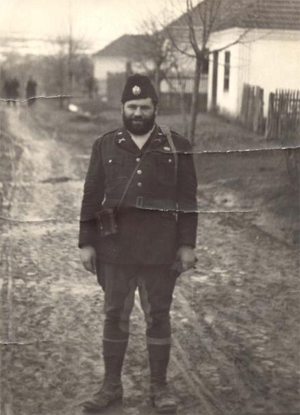

OSS 1st Lieutenant George Musulin behind enemy lines in German-occupied Serbia, as a Chetnik, during his first mission in November 1943. His second mission was Operation Halyard.

In 1943, the Office of Strategic Services set up operations in Istanbul.[13] Turkey, as a neutral country during the Second World War, was a place where both the Axis and Allied powers had spy networks. The railroads connecting central Asia with Europe, as well as Turkey's close proximity to the Balkan states, placed it at a crossroads of intelligence gathering. The goal of the OSS Istanbul operation called Project Net-1 was to infiltrate and extenuate subversive action in the old Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires.[13]

The head of operations at OSS Istanbul was a banker from Chicago named Lanning "Packy" Macfarland, who maintained a cover story as a banker for the American lend-lease program.[14] Macfarland hired Alfred Schwarz, a Czechoslovakian engineer and businessman who came to be known as "Dogwood" and ended up establishing the Dogwood information chain.[15] Dogwood in turn hired a personal assistant named Walter Arndt and established himself as an employee of the Istanbul Western Electrik Kompani.[15] Through Schwartz and Arndt the OSS was able to infiltrate anti-fascist groups in Austria, Hungary, and Germany. Schwartz was able to convince Romanian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Swiss diplomatic couriers to smuggle American intelligence information into these territories and establish contact with elements antagonistic to the Nazis and their collaborators.[16] Couriers and agents memorized information and produced analytical reports; when they were not able to memorize effectively they recorded information on microfilm and hid it in their shoes or hollowed pencils.[17] Through this process information about the Nazi regime made its way to Macfarland and the OSS in Istanbul and eventually to Washington.

While the OSS "Dogwood-chain" produced a lot of information, its reliability was increasingly questioned by British intelligence. By May 1944, through collaboration between the OSS, British intelligence, Cairo, and Washington, the entire Dogwood-chain was found to be unreliable and dangerous.[17] Planting phony information into the OSS was intended to misdirect the resources of the Allies. Schwartz's Dogwood-chain, which was the largest American intelligence gathering tool in occupied territory, was shortly thereafter shut down.[18]

The OSS purchased Soviet code and cipher material (or Finnish information on them) from émigré Finnish army officers in late 1944. Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, Jr., protested that this violated an agreement President Roosevelt made with the Soviet Union not to interfere with Soviet cipher traffic from the United States. General Donovan might have copied the papers before returning them the following January, but there is no record of Arlington Hall receiving them, and CIA and NSA archives have no surviving copies. This codebook was in fact used as part of the Venona decryption effort, which helped uncover large-scale Soviet espionage in North America.[19]

Weapons and gadgets

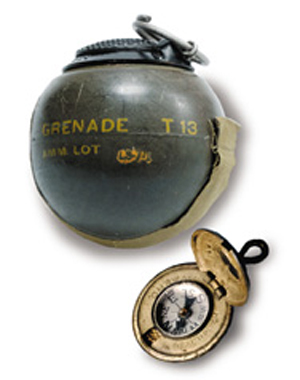

OSS T13 Beano Grenade and compass hidden in a button, CIA Museum

The OSS espionage and sabotage operations produced a steady demand for highly specialized equipment.[8] General Donovan invited experts, organized workshops, and funded labs that later formed the core of the Research & Development Branch. Boston chemist Stanley P. Lovell became its first head, and Donovan humorously called him his "Professor Moriarty".[20]:101 Throughout the war years, the OSS Research & Development successfully adapted Allied weapons and espionage equipment, and produced its own line of novel spy tools and gadgets, including silenced pistols, lightweight sub-machine guns, "Beano" grenades that exploded upon impact, explosives disguised as lumps of coal ("Black Joe") or bags of Chinese flour ("Aunt Jemima"), acetone time delay fuses for limpet mines, compasses hidden in uniform buttons, playing cards that concealed maps, a 16mm Kodak camera in the shape of a matchbox, tasteless poison tablets ("K" and "L" pills), and cigarettes laced with tetrahydrocannabinol acetate (an extract of Indian hemp) to induce uncontrollable chattiness.[20][21][22]

The OSS also developed innovative communication equipment such as wiretap gadgets, electronic beacons for locating agents, and the "Joan-Eleanor" portable radio system that made it possible for operatives on the ground to establish secure contact with a plane that was preparing to land or drop cargo. The OSS Research & Development also printed fake German and Japanese-issued identification cards, and various passes, ration cards, and counterfeit money.[23]

On August 28, 1943, Stanley Lovell was asked to make a presentation in front of a not very friendly audience of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, since the U.S. top brass were largely skeptical of all OSS plans beyond collecting military intelligence and were ready to split the OSS between the Army and the Navy.[24]:5–7 While explaining the purpose and mission of his department and introducing various gadgets and tools, he reportedly casually dropped into a waste basket a Hedy, a panic-inducing explosive device in the shape of a firecracker, which shortly produced a loud shrieking sound followed by a deafening boom. The presentation was interrupted and did not resume since everyone in the room fled. In reality, the Hedy, jokingly named after Hollywood movie star Hedy Lamarr for her ability to distract men, later saved the lives of some trapped OSS operatives.[25]:184–185

Not all projects worked. Some ideas were odd, such as a failed attempt to use insects to spread anthrax in Spain.[26]:150–151 Stanley Lovell was later quoted saying, "It was my policy to consider any method whatever that might aid the war, however unorthodox or untried".[27]

In 1939, a young physician named Christian J. Lambertsen developed an oxygen rebreather set (the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit) and demonstrated it to the OSS—after already being rejected by the U.S. Navy—in a pool at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington D.C., in 1942.[28][29] The OSS not only bought into the concept, they hired Lambertsen to lead the program and build up the dive element for the organization.[29] His responsibilities included training and developing methods of combining self-contained diving and swimmer delivery including the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit for the OSS "Operational Swimmer Group".[28][30] Growing involvement of the OSS with coastal infiltration and water-based sabotage eventually led to creation of the OSS Maritime Unit.

Facilities

At Camp X, near Whitby, Ontario, an "assassination and elimination" training program was operated by the British Special Operations Executive, assigning exceptional masters in the art of knife-wielding combat, such as William E. Fairbairn and Eric A. Sykes, to instruct trainees. Many members of the Office of Strategic Services also were trained there. It was dubbed "the school of mayhem and murder" by George Hunter White who trained at the facility in the 1950s.[31]

From these incipient beginnings, the OSS began to take charge of its own destiny, and opened camps in the United States, and finally abroad. Prince William Forest Park (then known as Chopawamsic Recreational Demonstration Area) was the site of an OSS training camp that operated from 1942 to 1945. Area "C", consisting of approximately 6,000 acres (24 km2), was used extensively for communications training, whereas Area "A" was used for training some of the OGs (Operational Groups).[32] Catoctin Mountain Park, now the location of Camp David, was the site of OSS training Area "B" where the first Special Operations, or SO, were trained.[33] Special Operations was modeled after Great Britain's Special Operations Executive, which included parachute, sabotage, self-defense, weapons, and leadership training to support guerrilla or partisan resistance.[34] Considered most mysterious of all was the "cloak and dagger" Secret Intelligence, or SI branch.[35] Secret Intelligence employed "country estates as schools for introducing recruits into the murky world of espionage. Thus, it established Training Areas E and RTU-11 ("the Farm") in spacious manor houses with surrounding horse farms."[36] Morale Operations training included psychological warfare and propaganda.[37] The Congressional Country Club (Area F) in Bethesda, Maryland, was the primary OSS training facility. The Facilities of the Catalina Island Marine Institute at Toyon Bay on Santa Catalina Island, Calif., are composed (in part) of a former OSS survival training camp. The National Park Service commissioned a study of OSS National Park training facilities by Professor John Chambers of Rutgers University.[38]

The main OSS training camps abroad were located initially in Great Britain, French Algeria, and Egypt; later as the Allies advanced, a school was established in southern Italy. In the Far East, OSS training facilities were established in India, Ceylon, and then China. The London branch of the OSS, its first overseas facility, was at 70 Grosvenor Street, W1.In addition to training local agents, the overseas OSS schools also provided advanced training and field exercises for graduates of the training camps in the United States and for Americans who enlisted in the OSS in the war zones. The most famous of the latter was Virginia Hall in France.[38]

The OSS's Mediterranean training center in Cairo, Egypt, known to many as the Spy School, was a lavish palace belonging to King Farouk's brother-in-law, called Ras el Kanayas.[39][40] It was modeled after the SOE's training facility STS 102 in Haifa, Palestine.[41] Americans whose heritage stemmed from Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece were trained at the "Spy School"[42] and also sent for parachute, weapons and commando training, and Morse code and encryption lessons at STS 102.[43][44][45] After completion of their spy training, these agents were sent back on missions to the Balkans and Italy where their accents would not pose a problem for their assimilation.[46][47]

Personnel

The names of all 13,000 OSS personnel and documents of their OSS service, previously a closely guarded secret, were released by the US National Archives on August 14, 2008. Among the 24,000 names were those of Carl C. Cable, Julia Child, Ralph Bunche, Arthur Goldberg, Saul K. Padover, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Bruce Sundlun, Rene Joyeuse MD and John Ford.[48][9][49] The 750,000 pages in the 35,000 personnel files include applications of people who were not recruited or hired, as well as the service records of those who served.[50]

OSS soldiers were primarily inducted from the United States Armed Forces. Other members included foreign nationals including displaced individuals from the former czarist Russia, an example being Prince Serge Obolensky.

Donovan sought independent thinkers, and in order to bring together those many intelligent, quick-witted individuals who could think out-of-the box, he chose them from all walks of life, backgrounds, without distinction to culture or religion. Donovan was quoted as saying, "I'd rather have a young lieutenant with enough guts to disobey a direct order than a colonel too regimented to think for himself." In a matter of a few short months, he formed an organization which equalled and then rivalled Great Britain's Secret Intelligence Service and its Special Operations Executive.

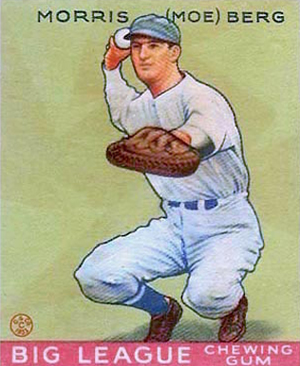

Major league baseball player Moe Berg of the Boston Red Sox was an OSS agent

One such agent was Ivy league polyglot and Jewish-American baseball catcher Moe Berg, who played 15 seasons in the major leagues. As a Secret Intelligence agent, he was dispatched to seek information on German physicist Werner Heisenberg and his knowledge on the atomic bomb.[51] One of the most highly decorated and flamboyant OSS soldiers was US Marine Colonel Peter Ortiz. Enlisting early in the war, as a French Foreign Legionnaire, he went on to join the OSS and earn the title of the most highly decorated US Marine in the OSS during World War II.[52]

Col. Peter Ortiz, USMC

Julia Child, who later authored cookbooks worked directly under Donovan.[53]

"Jumping Joe" Savoldi (code name Sampson) was recruited by the OSS in 1942 because of his hand-to-hand combat and language skills as well as his deep knowledge of the Italian geography and Benito Mussolini's compound. He was assigned to the Special Operations branch and took part in missions in North Africa, Italy, and France during 1943–1945.[54][55][56]

OSS created this false ID for Joe Savoldi - posing as Giuseppe De Leo while infiltrating the black market in Naples

One of the forefathers of today's commandos was Navy Lieutenant Jack Taylor. He was sequestered by the OSS early in the war and had a long career behind enemy lines.[57]

Taro and Mitsu Yashima, both Japanese political dissidents who were imprisoned in Japan for protesting its militarist regime, worked for the OSS in psychological warfare against the Japanese Empire.[58][59]

Nisei linguists

In late 1943, a representative from OSS visited the 442nd Infantry Regiment looking to recruit volunteers willing to undertake "extremely hazardous assignment."[60] All selected were Nisei. The recruits were assigned to OSS Detachments 101 and 202, in the China-Burma-India Theater. "Once deployed, they were to interrogate prisoners, translate documents, monitor radio communications, and conduct covert operations... Detachment 101 and 102's clandestine operations were extremely successful."[60]

Dissolution into other agencies

On September 20, 1945, President Truman signed Executive Order 9621, terminating the OSS. The State Department took over the Research and Analysis Branch; it became the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, The War Department took over the Secret Intelligence (SI) and Counter-Espionage (X-2) Branches, which were then housed in the new Strategic Services Unit (SSU). Brigadier General John Magruder (formerly Donovan's Deputy Director for Intelligence in OSS) became the new SSU director. He oversaw the liquidation of the OSS and managed the institutional preservation of its clandestine intelligence capability.[61]

In January 1946, President Truman created the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), which was the direct precursor to the CIA. SSU assets, which now constituted a streamlined "nucleus" of clandestine intelligence, were transferred to the CIG in mid-1946 and reconstituted as the Office of Special Operations (OSO). The National Security Act of 1947 established the first permanent peacetime intelligence agency in the United States, the Central Intelligence Agency, which then took up OSS functions. The direct descendant of the paramilitary component of the OSS is the CIA Special Activities Division.[62]

Today, the joint-branch United States Special Operations Command, founded in 1987, uses the same spearhead design on its insignia, as homage to its indirect lineage.

Branches

• Censorship and Documents

• Field Experimental Unit

• Foreign Nationalities

• Maritime Unit

• Morale Operations Branch

• Operational Group Command

• Research & Analysis

• Secret Intelligence[63]

• Security

• Special Operations

• Special Projects

• X-2 (counterespionage)

Detachments

• OSS Deer Team: Vietnam

• OSS Detachment 101: Burma

• OSS Detachment 202: China

• OSS Detachment 303: New Delhi, India

• OSS Detachment 404: attached to British South East Asia Command in Kandy, Ceylon

• OSS Detachment 505: Calcutta, India

US Army units attached to the OSS

• 2671st Special Reconnaissance Battalion

• 2677th Office of Strategic Services Regiment

In popular culture

Comics

• The OSS was a featured organization in DC Comics, introduced in G.I. Combat #192 (July 1976). Led by the mysterious Control, they operated as an espionage unit, initially in Nazi-occupied France. The organization would later become Argent.

• The alter ego of the DC Comics superheroine Wonder Woman, Diana Prince, works for Major Steve Trevor at the OSS. In this position, she found herself privy to intelligence on Axis operations in the United States, and many times foiled agents of Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy in their attempts to defeat the Allies and achieve world domination.

Films

• The Paramount film O.S.S. (1946), starring Alan Ladd and Geraldine Fitzgerald, showed agents training and on a dangerous mission. Commander John Shaheen acted as technical advisor.

• The film 13 Rue Madeleine (1946) stars James Cagney as an OSS agent who must find a mole in French partisan operations. Peter Ortiz acted as technical advisor.

• The film Cloak and Dagger (1946) stars Gary Cooper as a scientist recruited to OSS to exfiltrate a German scientist defecting to the allies with the help of a woman guerrilla and her partisans. E. Michael Burke acted as technical advisor.

• In the film Charade (1963 film) Carson Dyle Walter Mathau explains the CIA and OSS to Reggie Lampert Audrey Hepburn.

• In The Good Shepherd (2006), Matt Damon plays Edward Wilson, a Skull and Bones recruit who joins the OSS to help with a mission in London. He quickly gains rank as the head of the newly formed CIA's counterintelligence service.

• The biographical film Flash of Genius (2008) is about famed American inventor and OSS veteran, Robert Kearns.

• In the film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull 2008, it is indicated that Indiana Jones worked for the OSS and attained the rank of Colonel.

• In the film Inglourious Basterds (2009), directed by Quentin Tarantino, the titular "basterds" are members of an OSS commando squad in occupied-France, although no such OSS unit ever actually existed.

• The film Julie & Julia (2009) includes flashback scenes depicting Julia Child's wartime service with the OSS.

• The Real Inglorious Bastards (2012), a short film documentary, directed by Min Sook Lee, is about the OSS officers such as Frederick Mayer (spy), Hans Wijnberg, and Franz Weber, who volunteered to operate behind enemy lines, e.g., during "Operation Greenup", to defeat the German armed forces

• Camp X: Secret Agent School (2014), a YAP Films documentary for History Channel (Canada), portrays the first spy school in North America, OSS agents, their training at Camp X, and their missions behind enemy lines[64][65]

• World War II Spy School (2014), a YAP Films documentary for the Smithsonian Channel, portraying Camp X and the other training sites overseas, as well as OSS agents and their missions.[66]

Games

Tabletop Roleplaying Games

• The OSS appears in the backstory of Delta Green. The eponymous organization started as the fictional P4 Division of the Office of Naval Intelligence and in 1942 the ONI transfers the P4 division to the OSS so they can act in the entire Allied theater under the cover of a psychological warfare research division. It is under the OSS that the P4 Division acquires the codename Delta Green.

o The OSS also is mentioned in Pelgrane Press The Fall of DELTA GREEN. Player Characters can be ex-OSS agents in other agencies such as the CIA, which can be beneficial due the claim and carry authenticity, experience and authority due their past career in the OSS.

Video games

• In Call of Duty: World at War (2008), Dr. Peter McCain is an OSS spy.

• In Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine (1999), the main female character, Sophia Hapgood, is an OSS (later CIA) agent.

• Most games in the Medal of Honor video game franchise feature a fictional OSS agent as the main character.

• In the 2012 game Sniper Elite V2 and its prequels Sniper Elite III and Sniper Elite 4, the protagonist is an SOE turned OSS agent sniper.

• In the Wolfenstein series video game series, the main character is a member of a fictional organisation called the OSA (Office of Secret Actions), which is inspired by the OSS.

• In Tom Clancy's The Division 2, one of the games several hidden side missions, known as The Navy Hill Transmission, has the Agent searching the western part of Washington D.C. for the source of a mysterious encoded transmission which ends up leading him/her to an old underground OSS Bunker. During the side mission, Manny Ortega mentions a few interesting facts about the OSS and how President Truman disbanded it 1945 and how several former OSS agents went on to become part of the CIA. You also find a map that leads the Agent to a point of interest known as the "G. Phillips Protocol," which could possibly be in honor of George Phillips (USMC) (1926–1945), a US Marine and Medal of Honor recipient.

• It is featured in Hearts of Iron IV in the 2020 expansion, La Resistance, as the United States' Secret Agency.

Literature

• Jean Bruce's French pulp fiction series, OSS 117, follows the adventure of Hubert Bonisseur de la Bath, alias OSS 117, a French operative working for the OSS. The original series (four or five books a year) lasted from 1949 to 1963, until the death of Jean Bruce, and was continued by his wife and children until 1992. Numerous films were made from it in the 1960s, and in 2006 a nostalgic comedy was made, celebrating the spy movie genre, OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies, with Jean Dujardin playing OSS 117. A sequel followed in 2009 called OSS 117: Lost in Rio (original title in French: OSS 117: Rio Ne Répond Plus).

• Corey Ford and Alastair MacBain's book, Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of The Office of Strategic Services (1946), covers a broad overview of O.S.S. information and includes a chapter about Joe Savoldi titled, "The Saga of Jumping Joe" featuring a basic recounting of a portion of the McGregor Mission.

• W.E.B. Griffin's Honor Bound and Men At War series revolve around fictional OSS operations. Some of his characters in The Corps Series also are recruited by the OSS, notably Ken McCoy, Edward Banning, and Fleming Pickering.

• Roger Wolcott Hall's book, You're Stepping on My Cloak and Dagger (1957), is a witty look at Hall's experiences with the OSS.

• In Of Spies and Stratagems (1963), former OSS Deputy Director for Special Projects Stanley P. Lovell's book about the activities of his department, he recalls how he was recruited by Donovan, who was looking for his own Professor Moriarty; some of the devices Special Projects developed, from the High Standard silent, flashless pistol, to the anti-vehicle bomb codenamed Firefly, to a psychological warfare compound codenamed "Who? Me?"; the OSS's involvement in document forgery and counterfeiting; and hinted at the valor of its agents, which was only then starting to be revealed by the government.

• Clive Cussler deemed Patrick K. O'Donnell's book, Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs: The Unknown Story of the Men and Women of World War II's OSS (2004), "A revealing look into the intrigue and extraordinary courage of our intelligence gatherers of World War II. A rare combination of suspense thriller and true heroism by a great American writer."* David Stafford's book, Camp X (1986), is the most accurate account of the activities and personnel of Camp X, the secret agent training camp for sabotage and guerrilla warfare at Ajax near Oshawa Ontario, Canada, that was administered by the British Special Operations Executive.

• William Stevenson's book, A Man Called Intrepid: The Secret War (1976), describes the operations of the OSS, particularly the role of Sir William Samuel Stephenson, head of British Security Coordination in New York, in its formation.

• The OSS also appears in William Stevenson's book Intrepid's Last Case (1986).

Television

• In the American animated comedy series Archer, the character Malory Archer (mother of the main character Sterling Archer) is a former O.S.S agent.

• One of the characters in the Ellery Queen episode, "The Adventure of Colonel Niven's Memoirs" (1975), identifies himself as "Major George Pearson, O.S.S."; he offers some Soviet diplomats political asylum.

• In theNCIS: Los Angeles Season 3, episode, "Lange, H.", the O.S.S. is mentioned as the predecessor of the C.I.A.

• In 1957–1958 Ron Randell starred in the series O.S.S.[67]

• In Knight Rider, Devon Miles mentions that he served in OSS during World War II.

• In the X-Files Season 6 episode, "Triangle", the woman from the 1939 scenes portrayed by Gillian Anderson as Scully is a member of OSS.

See also

• United States portal

• World War II portal

• Charles Douglas Jackson

• Operation Halyard

• Operation Jedburgh

• Operation Paperclip

• OSS Detachment 101 operated in the China Burma India Theater of World War II.

• Paramarines

• Special Forces (United States Army)

• Special Operations Executive

• X-2 Counter Espionage Branch

• Central Intelligence Agency

• History of espionage

Notes

• Paulson, Alan (1995). "Required reading: OSS Weapons". Fighting Firearms. 3 (2): 20–21, 80–81.

• Brunner, John (1991). OSS Crossbows. Phillips Publications. ISBN 0932572154.

• Brunner, John (2005). OSS Weapons II. Phillips Publications. ISBN 978-0932572431.

References

1. Emerson, William K. (1996). "51". Encyclopedia of United States Army Insignia and Uniforms. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806126227.

2. Dawidoff, p. 240

3. Clancey, Patrick. "Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Organization and Functions". HyperWar. Retrieved November 10,2016.

4. "US Public Law 114–269 (2016)" (PDF). Retrieved February 21, 2018.

5. Stimson, Henry L. On Active Service in Peace and War (1948). per Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 16th ed.

6. The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-1945, p27-28

7. G.J.A. O'Toole, Honorable Treachery: A History of U. S. Intelligence, Espionage, and Covert Action from the American Revolution to the CIA pp 418-19.

8. Smith, R. Harris. OSS: The Secret History of America's First Central Intelligence Agency. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

9. "Chef Julia Child, others part of WWII spy network" Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, CNN, 2008-08-14

10. "Interview with Archimedes L. A. Patti". 1981.

11. Peter Broucek "Die österreichische Identität im Widerstand 1938–1945" (2008), p 163.

12. Hansjakob Stehle "Die Spione aus dem Pfarrhaus (German: The spy from the rectory)" In: Die Zeit, 5 January 1996.

13. Hassell and McCrae, p.158

14. Hassell and MacRae, p.159

15. Hassell and MacRae, p.166

16. Hassell and MacRae, p.167

17. Rubin, B: Istanbul Intrigues, page 168. Pharos Books, 1992.

18. Hassell and MacRae, p.184

19. Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili, The Mitrokhin Archive, Volume 1: The KGB in Europe and the West, 1999.

20. Waller, Douglas C. Wild Bill Donovan: The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage. New York: Free Press, 2011.

21. CIA Library: Weapons & Spy Gear Archived February 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Historical Document, March 15, 2007.

22. Brunner, John (1994). OSS Weapons. 58: Phillips Publications. ISBN 0-932572-21-9.

23. The Office of Strategic Services America's First Intelligence Agency. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs, Central Intelligence Agency, 2000, p. 33.

24. Hogan, David W. U.S. Army Special Operations in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, Dept. of the Army, 1992.

25. Breuer, William B. Deceptions of World War II. New York: Wiley, 2002.

26. Lockwood, Jeffrey Alan. Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects As Weapons of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

27. Lovell, Stanley P. (1963). Of Spies and Stratagems. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 79. ASIN B000LBAQYS.

28. Vann RD (2004). "Lambertsen and O2: beginnings of operational physiology". Undersea Hyperb Med. 31 (1): 21–31. PMID 15233157. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

29. Shapiro, T. Rees. "Christian J. Lambertsen, OSS officer who created early scuba device, dies at 93". Washington Post(February 18, 2011)

30. Butler FK (2004). "Closed-circuit oxygen diving in the U.S. Navy". Undersea Hyperb Med. 31 (1): 3–20. PMID 15233156. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

31. Albarelli, H.A. A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA's Secret Cold War Experiments 2009. p.67 ISBN 0-9777953-7-3

32. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "2" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service. p. 40. ISBN 978-1511654760.

33. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "Chapter 6: Instructing for Dangerous Missions" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. U.S. National Park Service. pp. 195–199.

34. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "2" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service. p. 40. ISBN 978-1511654760.

35. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "2" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service. p. 35. ISBN 978-1511654760.

36. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "11" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service. p. 558. ISBN 978-1511654760.

37. Chambers II, John Whiteclay (2008). "2" (PDF). OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service. p. 43. ISBN 978-1511654760.

38. "(U) Chambers-OSS Training in WWII-with Notes.fm" (PDF). Retrieved September 26, 2018.

39. Hueck Allen, Susan (2013), "7", Classical Spies: American Archaeologists with the OSS in World War II Greece, Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan, p. 134, ISBN 978-0472117697

40. Doundoulakis, Helias; Gafni, Gabriella (2014), "11", Trained to be an OSS Spy, Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, p. 99, ISBN 978-1499059830

41. Doundoulakis, Helias (2012), "1", I was Trained to be a Spy-Book II, Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, p. 2, ISBN 978-1479716494

42. Secret Intelligence (SI), Special Operations (SO), Morale Operations (MO) Archived May 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

43. Wilkinson, Peter; Foot, M. R. D (2002). Foreign Fields: The Story of an SOE Operative. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1860647796.

44. Horn, Bernd (2016). A Most Ungentlemanly Way of War. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 9781459732797.

45. "History" (PDF). http://www.nps.gov.

46. William J. Donovan, William Fairbairn, William Stephenson, Frank Gleason, Guy D'Artois, Helias Doundoulakis (2014). World War II Spy School (Film). USA, Canada: YAP Films.

47. [1] Archived March 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

48. Patrick, Jeanette (2017). "The Recipe for Adventure: Chef Julia Child's World War II Service". http://www.womenshistory.org. National Women's History Museum.

49. Blackledge, Brett J. and Herschaft, Randy "Documents: Julia Child part of WW II-era spy ring", Associated Press

50. Office of Strategic Services Personnel Files from World War II – overview page, search links, digital excerpts; National Archives Identifier 1593270: Personnel Files, compiled 1942 - 1945, documenting the period 1941 - 1945, from Record Group 226: Records of the Office of Strategic Services, 1919 - 2002; Personnel database – complete list

51. Lewin, Ben (Director) (2018). The Catcher Was a Spy (Movie). United States, Japan, Yugoslavia.

52. Lieutenant Colonel Harry W. Edwards. "A Different War: Marines in Europe and North Africa" (PDF). USMC Training and Education Command. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

53. "Julia Child Dished Out ... Spy Secrets?". ABC. August 14, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

54. Baminvestor (January 20, 2004). "English: OSS created this false ID for Joe Savoldi - posing as Giuseppe De Leo while infiltrating the black market in Naples". Retrieved February 19, 2017 – via Wikimedia Commons.

55. Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of the Office of Strategic Services Chapter IX "The Saga of Jumping Joe" page 150

56. Wild Bill Donovan: The Last Hero by Anthony Cave Brown page 352 and Savoldi's personal notes from July 8–16, 1943 (now in the possession of family members.)

57. "SEAL History: First Airborne Frogmen - National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum". NavySealMuseum.com. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

58. "Taro Yashima: an unsung beacon for all against 'evil on this Earth' - The Japan Times". The Japan Times. September 11, 2011.

59. "An unlikely heroine of World War II". SFGate. March 18, 2007.

60. "Japanese Americans in World War II Intelligence — Central Intelligence Agency". http://www.cia.gov. Retrieved February 22,2017.

61. George C. Chalou, ed. The Secret War (1992), pp 95-97.

62. Waller, Douglas "CIA's Secret Army", Time (2003)

63. For all branch information: Clancey, Patrick. "Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Organization and Functions". HyperWar. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

64. YAP Films (2014). Camp X: Secret Agent School. History Channel (Canada).

65. Camp X: Secret Agent School. IMDb. 2014.

66. YAP Films (2014). World War II Spy School. Smithsonian Channel.

67. O.S.S on IMDb

Further reading

• Albarelli, H.P. A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA's Secret Cold War Experiments (2009) ISBN 0-9777953-7-3

• Aldrich, Richard J. Intelligence and the War Against Japan: Britain, America and the Politics of Secret Service (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) ISBN 0521641861

• Alsop, Stewart and Braden, Thomas. Sub Rosa: The OSS and American Espionage (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946) OCLC 1226266

• Bank, Aaron. From OSS to Green Berets: The Birth of Special Forces (Novato, CA: Presidio, 1986) ISBN 0891412719

• Bartholomew-Feis, Dixee R. The OSS and Ho Chi Minh: Unexpected Allies in the War against Japan (Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2006) ISBN 0700614311

• Bernstein, Barton J. "Birth of the U.S. biological warfare program" Scientific American 256: 116 – 121, 1987.

• Brown, Anthony Cave. The Last Hero: Wild Bill Donovan (New York: Times Books, 1982) ISBN 0812910214

• Brunner, John W. OSS Weapons. Phillips Publications, Williamstown, N.J., 1994. ISBN 0-932572-21-9.

• Brunner, John W. OSS Weapons II. Phillips Publications, Williamstown, N.J., 2005. ISBN 978-0932572431.

• Brunner, John W. OSS Crossbows. Phillips Publications, Williamstown, N.J., 1991. ISBN 0-932572-15-4.

• Burke, Michael. "Outrageous Good Fortune: A Memoir" (Boston-Toronto: Little, Brown and Company)

• Casey, William J. The Secret War Against Hitler (Washington: Regnery Gateway, 1988) ISBN 089526563X

• Chalou, George C. (ed.) The Secrets War: The Office of Strategic Services in World War II (Washington: National Archives and Records Administration, 1991) ISBN 0911333916

• Chambers II, John Whiteclay. OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II (NPS, 2008) online; chapters 1-2 and 8-11 provide a useful summary history of OSS by a scholar.

• Dawidoff, Nicholas. The Catcher was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg ( New York: Vintage Books, 1994) ISBN 0679415661

• Doundoulakis, Helias. Trained to be an OSS Spy (Xlibris, 2014) OCLC 907008535. ISBN 9781499059830[self-published source]

• Dulles, Allen. The Secret Surrender (New York: Harper & Row, 1966) OCLC 711869

• Dunlop, Richard. Donovan: America's Master Spy (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1982) ISBN 0528811177

• Ford, Corey. Donovan of OSS (Boston: Little, Brown, 1970) OCLC 836436423

• Ford, Corey, MacBain A. "Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of O.S.S." (New York: Random House 1945,1946) OCLC 1504392

• Grose, Peter. Gentleman Spy: The Life of Allen Dulles (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994) ISBN 0395516072

• Hassell, A, and MacRae, S: Alliance of Enemies: The Untold Story of the Secret American and German Collaboration to End World War II, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. ISBN 0312323697

• Hunt, E. Howard. American Spy, 2007

• Jakub, Jay. Spies and Saboteurs: Anglo-American Collaboration and Rivalry in Human Intelligence Collection and Special Operations, 1940–45 (New York: St. Martin's, 1999)

• Jones, Ishmael. The Human Factor: Inside the CIA's Dysfunctional Intelligence Culture (New York: Encounter Books, 2008, rev 2010) ISBN 9781594032745

• Katz, Barry M. Foreign Intelligence: Research and Analysis in the Office of Strategic Services, 1942–1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989)

• Kent, Sherman. Strategic Intelligence for American Foreign Policy (Hamden, CT: Archon, 1965 [1949])

• Lovell, Stanley P. (1963). Of Spies and Stratagems. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 79. ASIN B000LBAQYS.

• McIntosh, Elizabeth P. Sisterhood of Spies: The Women of the OSS (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998) ISBN 1557505985

• Mauch, Christof. The Shadow War Against Hitler: The Covert Operations of America's Wartime Secret Intelligence Service (2005), scholarly history of OSS.

• Melton, H. Keith. OSS Special Weapons and Equipment: Spy Devices of World War II (New York: Sterling Publishing, 1991) ISBN 0806982381

• Moulin, Pierre. U.S. Samurais in Bruyeres (CPL Editions: Luxembourg, 1993) ISBN 2959998405

• Paulson, A.C. 1989. OSS Silenced Pistol. Machine Gun News. 3(6):28-30.

• Paulson, A.C. 1995. OSS Weapons. Fighting Firearms. 3(2):20-21,80-81.

• Paulson, A.C. 2002. HDMS silenced .22 pistols in Vietnam. The Small Arms Review. 5(7):119-120.

• Paulson, A.C. 2003. WWII vintage silent .22LR [High Standard OSS HDMS pistol]. Guns & Weapons for Law Enforcement. 15(2):24-29,72.

• Persico, Joseph E. Roosevelt's Secret War: FDR and World War II Espionage (2001).

• Persico, Joseph E. Piercing the Reich: The Penetration of Nazi Germany by American Secret Agents During World War II (New York: Viking, 1979) Reprinted in 1997 by Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 076070242X

• Peterson, Neal H. (ed.) From Hitler's Doorstep: The Wartime Intelligence Reports of Allen Dulles, 1942–1945 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996)

• Pinck, Daniel C. Journey to Peking: A Secret Agent in Wartime China (Naval Institute Press, 2003) ISBN 1591146771

• Pinck, Daniel C., Jones, Geoffrey M.T. and Pinck, Charles T. (eds.) Stalking the History of the Office of Strategic Services: An OSS Bibliography (Boston: OSS/Donovan Press, 2000) ISBN 0967573602

• Roosevelt, Kermit (ed.) War Report of the OSS, two volumes (New York: Walker, 1976) ISBN 0802705294

• Rudgers, David F. Creating the Secret State: The Origins of the Central Intelligence Agency, 1943–1947 (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2000) ISBN 0700610243

• Smith, Bradley F. and Agarossi, Elena. Operation Sunrise: The Secret Surrender (New York: Basic Books, 1979) ISBN 0465052908

• Smith, Bradley F. The Shadow Warriors: OSS and the Origins of the CIA (New York: Basic, 1983) ISBN 0465077560

• Smith, Richard Harris. OSS: The Secret History of America's First Central Intelligence Agency (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972; Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2005) ISBN 0520020235

• Steury, Donald P. The Intelligence War (New York: Metrobooks, 2000)

• Troy, Thomas F. Donovan and the CIA: A History of the Establishment of the Central Intelligence Agency (Frederick, MD: University Publications of America, 1981) OCLC 7739122

• Troy, Thomas F. Wild Bill & Intrepid (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996) ISBN 0300065639

• Waller, John H. The Unseen War in Europe: Espionage and Conspiracy in the Second World War (New York: Random House, 1996) ISBN 0679448268

• Warner, Michael. The Office of Strategic Services: America's First Intelligence Agency (Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 2001) OCLC 52058428

• Yu, Maochun. OSS in China: Prelude to Cold War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996) ISBN 159114986X

External links

• "The Office of Strategic Services: America's First Intelligence Agency"

• National Park Service Report on OSS Training Facilities

• Collection of Documents at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Museum and Library, Part 1 and Part 2

• The OSS Society

• OSS Reborn

• Works by Office of Strategic Services at Project Gutenberg

• Office of Strategic Services collection at Internet Archive

• Works by or about Office of Strategic Services at Internet Archive

• Works by Office of Strategic Services at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)